| 03 | Writing a Business Plan |

Chances are, you’ve never had to write a business plan until now. Maybe you’ve never even heard of such a thing. So let’s begin at the beginning: What’s a business plan? What kind of information does it include? What’s it for?

A business plan is a detailed description of your proposed business: What kind of business will it be? Who will own it? Where will it be located? Who will your clients be? What geographical areas will your business serve? What kinds of products or services will it offer? Who’s the competition? How will your business be better than or different from the competition? How will your services be advertised to the potential clients? What kinds of equipment will you need to start up? What are your other start-up costs? What will the total costs be to start the business? What will the overhead be? When will your business begin to show a profit? What are the seasonal variations in sales? Will there be employees? How many? What kind—laborers, supervisors, office help? What will the cash flow be for the first few years? How much money do you need in order to make a living and put something away for your retirement? These are some of the important issues that the business plan addresses.

Though you can find plenty of books that provide ready-made business plan formats, there’s no universally accepted way to prepare one. In fact, the way your business plan is organized will depend to some extent on how you’ll be using it. First, decide if you’ll be using the plan to attract capital: a bank loan, money from Uncle Harry, Small Business Administration financing, or whatever. You’ll tailor the business plan to the source of funds. For example, a bank is interested in how you’re going to pay off the loan. They’ll be justifiably cautious in loaning money to something as risky as a landscaping business. They’ll want to see lots of financial projections: five years’ pro forma (projected) income statements and balance sheets, and other evidence of your good financial planning. On the other hand, Uncle Harry might be more interested in the personal or philosophical aspects of his descendant’s proposed business, perhaps even assuming he will never get a significant return on his investment.

If you won’t need start-up capital, then the plan is mostly for you and possibly for key employees when you expand someday. It’ll be a road map to guide you as you develop your business. Though you still have to do the financial projections (trust me, you do), you can format the plan more to your own liking.

Either way, there are some essential elements the business plan must contain, and there’s a systematic approach to preparing it that will make it pretty easy for you to get the job done well. I’m going to give you my version of what a business plan for a small gardening or landscaping business should look like and how to go about writing it. That’s what we’ll spend most of this chapter on; but first, let’s deal with the obvious question.

Thinking about actually preparing a business plan may give you a bad case of anxiety. “Hey,” you may ask, “isn’t this all a waste of time? After all, I’m not starting Wal-Mart! Why not just get some jobs and start making money?”

The answer is, this is not just a job, it’s a business. It has to function smoothly over the long haul. It’s complex, and your success depends on your understanding, in depth, what you’ll be doing and why—understanding it now, before you begin. You wouldn’t build a garden by going out and buying any old plants and throwing them into the ground any old way. That would lead to a mess, not a garden. You plan first, then plant. Similarly, your business needs guidance and form right from the beginning, and that’s what a business plan is all about. It’s a plan for success.

Let’s hope you’ll do really well and attract a lot of business. That would be great, but if you don’t have management systems in place first, you’ll soon be overwhelmed and your initial success will be compromised by your struggles to get organized in the midst of lots of activity rather than in advance as it should have been. Your business plan forces you to develop, in nitty-gritty detail, a strategy for exactly how you’ll do things—marketing, hiring, financing, and a lot more. That way, you can create a business that really works. As your business grows, your business plan will continue to guide your development and help you prosper.

Speaking of financing, you may very well need some money for your start-up business. Remember how costly those tools and equipment are? Well, if you go to the bank and tell them you want to start a landscaping business and you’d like, say, $50,000, what’s the first thing they’re going to do? That’s right! They’re going to say, “Let’s see your business plan.” You don’t want to be caught short at this important moment. Even good old Uncle Harry, if he’s got anything on the ball, will ask for a business plan before he empties part of his bank account into yours.

Putting together a business plan, while certainly not as much fun as a week at the seashore, isn’t all that bad. Parts of the job are even enjoyable. It’ll give you a lot of clarity about your new business. When you’re done, you’ll have new confidence and enthusiasm, knowing that you’re well prepared for your adventure.

Finally, a business plan doesn’t have to be fancy. There are certain tasks you want your business plan to accomplish. Accomplish them and stop. No glossy printing, no vast acreage of numbers, no frills. A business plan is like a shovel; it’s a tool, nothing more.

When do you prepare a business plan? Easy: before you commit any significant time or money to the business. Don’t put this off as you would cleaning behind the fridge. Get it done. Remember: business plan first, business second. (Tip: Visit the website of the Service Corps of Retired Executives [“SCORE”] at www.score.org to find some cool business plan templates, helpful advice, and even a hot line you can use for personal assistance. It’s free!)

OK, this isn’t going to be all that difficult. Just follow the steps below, answering questions as you go. Take the time to develop realistic numbers and projections rather than just making up a number to get the job over with. Do a good job on this and you’ll have a tool that will serve you and your new business well.

Step One: A Statement of Purpose

Can you describe in thirty-five words or less what your new business is all about? If not, maybe you’re not too sure yourself. Hammering out a Statement of Purpose, though it may seem silly, is a terrific way to focus your mind on what you’re doing and boil it down to one pithy definition that you can use to remind yourself (and everyone else) what your business is about. Try it. To help you get the idea, here’s a statement a friend of mine developed (with the help of his employees) for his landscaping business:

Boulder Creek Landscaping Company is a quality-oriented organization specializing in ecological enhancement of the environment for the benefit of the entire community.

So, ask yourself . . . will you just be doing landscaping? Not really. You’ll also be serving the needs of your clients, your employees, your suppliers, the community, and the environment. You’ll be a business manager, an employer, a public relations person, and more. Each task and each role you play takes a place within the ecology of your little business. Which ones are the most important to you? Use your statement of purpose to define the basic character of your business. Then frame it and hang it right in the middle of your bulletin board, or put it on your desk where you’ll see it every day.

Step Two: General Information about Your Business

This is the place for some very basic facts about your proposed business. What general classes of service will you offer (maintenance, new landscaping, etc.)? Where will your business be located (your spare bedroom)? Who will own it (just you, you and your spouse, two or more partners)? What will the form of the business be (sole proprietorship, partnership, LLC, corporation)? When do you plan to start doing business? What will the name of your business be?

Choosing a company name can be difficult. After all, your company name will be with you for a long time. Select something that sounds solid, not frivolous. Make sure it’ll appeal to a wide range of people. Avoid trendy names that’ll sound dated in a few years (imagine if your company name was Frieda’s Far-Out Garden Service). Make sure the name conveys what you do. Finally, be sure you choose something that makes sense. Many years ago there was a company in my town called Inner-Plant-A-Terrarium. Seriously. I never did figure out why they chose such a goofy moniker, but it didn’t matter because they weren’t around for very long.

Step Three: Your Background

One of the goals of the business plan is to try to convince potential investors of your management and technical skills. Here’s where you sell yourself.

Write a couple of paragraphs telling how you came to be interested in land-scaping and why you’ve decided to go into business. Describe any applicable training or degrees you have, your employment experience, volunteer work, and anything that demonstrates your dedication to your profession. If you don’t have any professional experience but have always had a beautiful backyard, put that down; it counts, too. (Naturally, the background description applies to partners and any other key employees whom you propose to have on board when you start up.) The bank will need to see this information, just as a prospective employer needs to see a résumé. It’ll be good for you, too, giving you a clear perspective on where you’ve come from and why you’re qualified to follow this dream of business ownership. Remember, keep it brief and to the point. Finally, mention any licenses you will need for the services you offer and indicate whether you have them yet.

Step Four: Services Offered

In detail, tell what you plan to offer your clients. Do you want to specialize in water gardens, organic lawn care, or commercial landscaping? Do you want to do design/build landscape installation? Irrigation troubleshooting? Pest control? Are you interested in selling any products in addition to services? What are they? The chart that follows lists some of the services typically offered by small gardening and landscaping companies.

Consider, too, what you’ll do in the off-season. Many companies offer snow removal service or holiday light installation, for example, to keep crews busy and produce income.

Your decisions should be based in part on what you like to do, of course, but also on what services the community needs and will purchase from you. You may want to do water gardens, but if nobody’s interested in having one you’ll have a hard time making a go of it. It might be easier to mow lawns or do irrigation work or whatever else is in demand. And trust me, the smart money is not with snow removal services in south Florida.

Remember, too, that most successful businesses offer a range of services. I’ve always done well because I tried to do whatever people wanted, as long as I had the necessary skills, and it made sense in other ways. There are limits, of course, but the point is to try to serve people’s needs. (An old business adage, one worth following, is to “find a need and fill it.”) Try to never say no. If you’re not capable of doing a job, find someone who is and use that person as a subcontractor (then learn by watching him or her). So, prepare your business plan with a wide spectrum of services in mind. After due consideration, you may want to narrow your focus somewhat (some people are successful because they pursue a small niche), but start with the broad view.

Is there something different about your business? Will you offer all-organic lawn care, landscaping with native plants, or construction using recycled materials? Do you plan to include a year’s free monthly inspections with each landscape? Say so. Investors often equate innovation with potential for success. If your ideas are good, they’ll make a favorable impression.

Step Five: Markets

Who will your clients be? Homeowners? Contractors? Property managers? Developers? Architects? Landscape architects? Realtors? Apartment house owners? Owners of commercial property? Federal, state, or local governments? Will you focus on young families, middle-aged homeowners, or retired people? What will their income level be? (Do you see how a business plan forces you to answer all kinds of pointed questions?)

Now, how many of these people are out there? Ten? Ten thousand? Ten million? How many will you need to attract? How do you find this stuff out? For some categories, it’s easy. For instance, if you’re interested in working with Realtors, get a head count from the websites of local realty companies. Others are more difficult, such as apartment house owners, because they don’t advertise anywhere. But I bet there’s an association of apartment house managers or something similar in your community. Ask around. Your local library probably has a reference desk that’s staffed with nice people who can help you research the most obscure things, and they are usually better at it than an inexperienced person surfing the web with-out knowing what to look for or how to find it (they have access to special search engines, too). Give them a call or stop by.

Next, where are these potential clients located? That is, how far afield are you willing to go to look for business? (For starters you’ll probably want to stick to your local community. It’s too much to try to become Statewide Landscaping Company right away; long-distance projects are harder to manage, and the travel time and vehicle expenses make your services too costly to be competitive with those of local companies.)

How many potential clients live in your community? How many people move into your community each year? What percentage of these people do you intend to grab away from the competition in the first year, two years, five years? The marketing people call this market penetration. It’s an important question because you need to know not only what the potential for your company is but also how much business you’ll need to do to be successful. This also relates to the financial projections we’ll be getting to soon. (Tip: Find all sorts of useful and interesting facts about your community at www.city-data.com.)

Finally, take a look at overall industry growth trends to see whether your strategy is really viable. In other words, is the work actually out there? For example, if you choose to only landscape new homes, working for builders and developers, make sure there’s going to be a sufficient volume of new construction in your area over the next couple of decades. If not, you’re kidding yourself about your potential success. (Tip: Do an Internet search for “landscape industry growth” to access articles on this subject.)

Step Six: Competition

You won’t be the only one out there. Searching on the Internet for “landscaping [your community name]” is the best way to size up the competition. You’ll quickly see who’s in the business and what kind of services they provide, whether they give free initial consultations, give discounts to seniors, or offer things that you may not have thought of. Websites are also a good indication of the quality of your competition; if they have a hokey website they may be a hokey operation all around, and vice-versa.

Gardening Jobs versus Landscaping Jobs

GARDENING

Lawn care (mowing and edging, fertilizing, pest control, weeding, aerating, renovating, overseeding)

Plant care (pruning and hedge trimming, fertilizing, pest control, weeding, replanting, mulching)

Tree care (pruning, fertilizing, pest control, cabling and bracing, usually for smaller trees only)

General cleanup and refuse management (sweeping, washing down walks, trash hauling, composting)

Irrigation maintenance (replacing sprinkler heads, repairing valves, etc.)

Water management (watering, programming automatic controllers)

LANDSCAPING

Lawn installation (sod and seeded lawns)

Plant installation (annuals, perennials, shrubs, trees, food gardens, etc.)

Tree planting and transplanting, guying and staking

Hardscape construction (walks, retaining walls, fences, patios, planters, decks, arbors, etc.) and lighting installation (low-voltage walkway and landscape lights)

Irrigation installation (sprinklers and drip systems, water mains, backflow devices, automatic controllers, etc.)

Drainage system installation (grading, drainpipes, catch basins, etc.)

Water features (ponds, fountains, streams, etc.)

In my community there’s a pretty consistent 50 percent turnover of landscape companies every year. Scary? You bet, but don’t be discouraged. Most of those people didn’t take an orderly approach to business management like you’re doing. They crippled themselves with ignorance and lack of professionalism right from the get-go. And they probably had one or more serious flaws in their service, leading clients to quickly abandon them and even spread word of their crummy service to their friends and via Yelp, Angie’s List, and other online review sites. You’ll do better. (By the way, somebody needs to step in to service the clients who are abandoned by these failures. Why not you?)

Because most gardening and landscaping companies are privately owned, it’s pretty much impossible to find out what their sales volume is, how many employees they have, or how profitable they are. Even if you’ve seen a company’s shiny new trucks running around town, it doesn’t mean they’re profitable. It also doesn’t mean their clients are satisfied with the services they offer. Remember, to be successful you need to be better than the competition at keeping clients happy, not necessarily flashier or bigger.

One good way to learn about competing companies is to ask a few questions of their suppliers, such as nurseries, irrigation supply houses, and other vendors. Ask them who’s busy, what kinds of work are available, and who’s doing what. Find out who’s hiring. You might even learn who’s behind in their bills.

Another approach is to apply for work with a few companies, even though you’re not looking for a job. This is a little underhanded, but business isn’t always pretty. During an interview, you can probe for information about the company and get a good inside look at their operation. You can even bring up the subject of other companies and get some interesting dirt. Remember, of course, that not everything you hear will be true. You’ll need to read between the lines. (Who knows, maybe you’ll end up working for one of these companies for a while.)

Once you’ve gathered information, you need to write a short summary and evaluation of the results. How many companies are there? How many are large, how many small? What’s the sales volume? How many people are employed locally? What are the major services being offered? To whom? Who’s booming and who’s just hanging on?

Finally, how will you fit in? Which competitors are the most important to you and why? How will you draw business away from them? (Tip: Maybe you could offer your competitors some kind of service that they aren’t set up for or interested in doing. Some examples would be irrigation work, backflow preventer testing, leak detection, pest management, or small equipment repair.) Why will your business be better? Be brief, but be specific.

Step Seven: Marketing

How are you planning to attract business? That’s what marketing is all about. Read chapter 6 and then choose strategies that are right for the type of business you’re after, the clients you’re interested in, and the economic conditions in your area.

Pricing

Describe your price strategy in detail. Are you planning to appeal to small clients by offering low prices and discounts for seniors, or will you be trying to attract top-end work where prices are high? Will you offer specials or coupons to get new clients? An hour’s free consultation? Special prices on the first month’s garden service? Internet-only discounts to track your website traffic?

Warning: One of the most annoying and potentially deadly problems in this business is “low-balling” competitors—cut-rate operators who somehow get by charging less than the actual cost of the job for their work. There are many variations on the basic theme (see chapter 7), but for now be aware that low-ballers exist. They drive prices below the profit level for everyone, and they may affect you, especially if you plan to enter into the cutthroat world of competitively bid maintenance or landscaping jobs.

Low-ballers never go away (a new crop sprouts every year like crabgrass), but they really come out of the woodwork during difficult economic times or when there’s very little work around. So, before you get too far, check out the situation in your area. You can still do fine even with a heavy population of low-ballers, but you’ll need to avoid going head-to-head with them. Stick to custom work, provide top-quality service, and retain your clients. Don’t waste your time and resources getting into bidding wars because even if you get some jobs you’ll make little or no money on them.

Advertising

How will people find out about you? Will you go door-to-door? Send out direct-mail pieces? Join the chamber of commerce and network with influential businesspeople? Advertise on radio or in the local newspaper? Market through your own website? Develop a Facebook page? Stand on the corner in a gorilla suit? What? Tell it.

Show it, too. Do a mock-up of your proposed advertising in print and on your website. Lay out any brochures and handouts you plan to use. You’ll force yourself to see whether you actually like your ideas once they’re on paper.

If you plan on working with an advertising agency, a web designer, or a graphics company, describe the work they’ll be doing for you.

Next, describe the results you expect to get from your marketing program. That is, X dollars invested in marketing should produce Y dollars in sales. Be realistic. For example, direct-mail campaigns usually produce a 2 or 3 percent response. Believe it or not, that’s considered a success. If you project a 50 percent response, you’ll look like a rube to investors. Plus, you’ll be in for a shock when you put your plan into action.

Remember to think about both short-term and long-term strategies. That is, you’ll probably do one set of things to get started and then switch to a different set once you’re rolling. What’s different about them? Why? Justify your choices.

Step Eight: Company Organization

In years one through five, how many employees will you have and what are their duties? Who answers to whom?

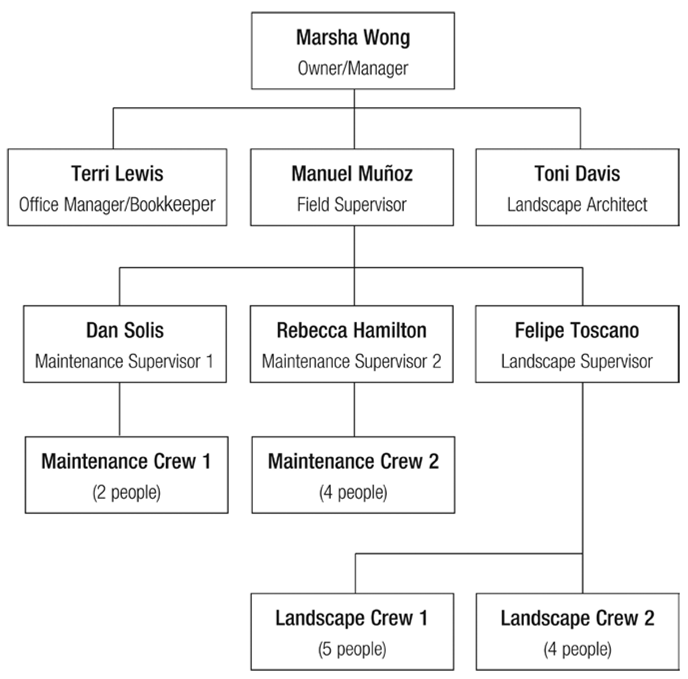

Let’s have a quick look at big versus small. The first year, your organizational chart may look like this:

Yes, that looks pretty silly, but still, there’s no shame in being a one-person operation. By year five, it may look like this flowchart:

Now you’ve got twenty-two mouths to feed (plus their families), plus casual labor brought in as conditions warrant, subcontractors, consultants, and who knows what else. You’ve got a big, consumptive company on your hands, and you’d better know how to run it. Here’s where lack of management skills can do you in quickly.

Big versus Small

Though “big” looks a lot like “successful” to most people who haven’t been there, “big” is actually a whole lot riskier, more stressful, and more unstable than “small.” Here’s why: If you’re little Joe Gardener working out of the spare bed-room, your overhead is practically nonexistent, the volume of work you need to do in order to get by is minimal, your exposure to risk is small, and you can easily keep a lot of things in your head without losing control. (Does working out of your home start to make sense now?)

Get big, and you’ve got a lot of potential problems. First, you have people (including yourself) who are part of the overhead of the business—in the previous example, the office manager, the field supervisor, and possibly the landscape architect. You can’t bill for their time like you can for the laborers, but they cost you lots of money nonetheless (maybe more than the laborers whose work pays all the bills, including overhead). They’re probably on salary, which means you have to pay them even if business is slow. That can drain you dry in no time.

Similarly, you’ve suddenly got an office, a storage yard, equipment loans, upkeep on everything, and lots more insurance. All this is overhead, it’s all expensive, and it can’t be shut off. So the rules of the game change. Suddenly, you’ve got to sell jobs like crazy because you need so much more cash every month. Your over-head has gone from literally a few dollars per day in the good old spare bedroom days to many thousands per month with the big fancy outfit. Naturally, doing all that work exposes you to more liability—defects, accidents, lawsuits. And, of course, sooner or later those employees will start to give you problems, such as injuries, theft, substance abuse, and personal conflicts.

How do you control this huge organism? When do you find time to stop by all your many jobs that may be scattered over two or three counties? How do you know if you’re making any money? When do you have any time for yourself?

Most companies that start to grow hit the “in between” stage of 2 to 15 or so employees that is one of the most challenging periods in the life of a small business. A company that size is too small to have the resources or the earnings potential of a larger operation, but too big to enjoy the simplicity of a one-person show. That’s not to say you can’t make money with an outfit that size, but it takes special effort and a bit of luck to make it.

The point is, now is a good time to think hard about whether your goals include eventually getting big. Let’s hope that you understand that there’s a world of difference between the small home-based business with maybe one or two employees and the big company downtown. What about that fifth year? Unless you’re up for the challenge of running a business in addition to doing landscaping, maybe you’ll be a lot happier if you’re still working by yourself or with a helper out of your spare bedroom.

You might have guessed that I favor staying small. I got bigger for a while, with 5 trucks and a bunch of employees and an office manager, but I soon decided that even though I could probably learn to handle it as well as the next person, I didn’t want to do so. I like running a really small business because it’s safer, more fun, and just as profitable if you play your cards right. Most people think getting big is an inevitable aspect of business success, but that’s folly. If you just want to earn a living, you can do that just as well with a tiny operation as with a big one. Ask yourself whether you are trying to build an empire or do landscaping work, because those are two really different things. Always run your business with your head, not your ego. If you decide to get big, be sure that it makes business sense, that you can handle it, and that you want that kind of life.

Now, all this drives your sales and staffing projections. Once you’ve decided how big to be, it’s easy to figure out how many people you’ll need. (Refer to chapter 5 for a rundown on the wonderful world of employees, and use the information to calculate your staffing needs year-by-year for the first five years.)

Briefly describe what employees will do, whether they’ll be full or part time, permanent or temporary, and whether they’ll be part of overhead or of cost of sales. Tell how much you’ll pay them. Indicate what the labor burden will be (worker’s compensation insurance, social security taxes, fringe benefits, and so forth). Describe vacation and sick-leave policies, paid holidays, and so forth.

Also describe how you’ll use subcontractors and outside services. Justify all staffing that’s not part of the cost of sales (that is, any employees that don’t generate a profit through billable hours and are therefore a drag on profits)—do you really need an office manager, for example, or is that something you can handle yourself in the early stages of your company?

Step Nine: Facilities and Equipment

Based on the sales volume for each year, describe the kinds of equipment you’ll need to own, lease, or rent (tools, vehicles, heavy equipment, office furnishings, etc.) and the kind, location, and size of facilities you’ll need (office space, storage yard, employee facilities, etc.).

For instance, if you plan to have two gardening crews in year three, that means you’ll need two trucks (plus a truck or other vehicle for yourself unless you’re part of one crew), two sets of tools and equipment, and a place to store it all. You may or may not need a bigger office; this is still a reasonable-sized company to run from home, provided the employees don’t create a nuisance for the neighbors.

Add up what all this will cost, item-by-item and year-by-year. Don’t forget to allow for inflation in the cost of future purchases. (Tip: It’s not easy to calculate future costs. Doing a web search on “how to predict inflation” will produce a bunch of numbers-heavy articles and calculators that take more math chops than I have to understand them, and that may or may not prove to be accurate. I wish I had an easy answer for you on this one. Try looking up the Consumer Price Index (“CPI”) and extrapolating forward based on past increases. One thing’s for sure: your costs will change over time and that needs to be taken into account in your projections.)

Step Ten: Financial Projections

OK, we’ve put this off long enough. Now that you know what you’re planning to do for the next five years, you need to get down to the details of how much money this is going to cost and how much you’re going to make. Here are some questions your number crunching is going to answer:

1. What are my start-up costs?

2. How do I plan to meet those costs?

3. What’s my cost of doing business (years 1–5)?

4. What are my projected sales (years 1–5)?

5. What are my projected profits (years 1–5)?

6. What’s my equity (years 1–5)?

7. What’s my cash flow (years 1–5)?

8. What accounting and control systems will I have?

How will you answer all these questions in an orderly way that others will understand? Well, there are several standard formats for presenting this information that are universally accepted and are required in any business plan. These include the following:

Add a form for start-up costs and a description of your accounting system, and you’ve got it. Yes, this is going to hurt, but not that much. You may even find it interesting. But just in case you’re tempted to skip this part, here’s a BIG WARNING: If you’re not the numbers type, then get a job. You haven’t got what it takes to run a business. Running numbers regularly is how you keep track of whether your business is making money or not, and it’s how you predict your cash flow, which is critical in a seasonal business like landscaping.

Nobody cares whether you make money or go broke. The only way you’ll make money is to keep track of everything via the income statement and the balance sheet. Do this now, and do it regularly after you’re actually in business. Skip it, and you’ll probably go broke. It’s that simple and that cruel. The successful business owner manages money well, no matter what type of business he or she has. Now let’s get to work.

Start-up Costs

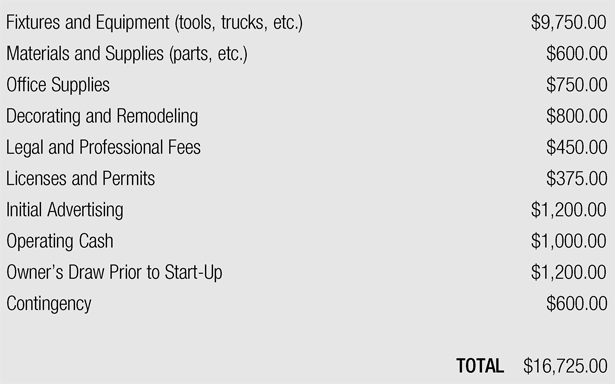

Make a list of all the things you’ll need on your first day in business. It should look something like the “Estimated Start-up Costs” form (see later in chapter).

The total is the amount of money you’ll need to set up your business. (Note: The figures shown are examples only. Don’t use them for your own start-up costs.) Most of these are pretty easy to figure out. Be realistic about the cost of things, and allow enough to cover actual costs. For example, don’t figure you’ll spend $1,000 for a truck, because you know you can’t get a reliable one for that price. Even if you could find one at such a low price, it would certainly soon break down, and the repairs could possibly cost more than the purchase price. Some costs, such as advertising, you simply carry forward from your work in previous sections of the business plan. Others require a little homework.

A couple of items need to be explained. Operating Cash is the money you’ll need to run the business until it becomes profitable. (Warning: The chief cause of failure for start-up businesses is insufficient start-up cash. Be sure you have enough.) Ever optimistic, new business owners assume all they have to do is hang their sign out and in no time they’ll be driving around in a fancy European sedan, and flying their private jet to Paris for lunch. Sorry, but there’s just no way that’s going to happen no matter how talented or optimistic you are. If you have debts, you’ll have to service them. That’s a fancy banker’s way of saying that you have to pay off your loans, and that money has to come from whatever work you manage to find. Also, you may not have a lot of business at first but your overhead costs will still need to be paid. Finally, it’ll take you a while to figure out how to make a profit, especially if you just quit your job at the burger stand, so even though business may be brisk you could lose money for a while. The bottom line? You have to have funds to cover yourself while you’re getting started. (You’ll get an exact amount for this item after you’ve done your cash-flow projections in a little bit. For now, leave it blank.)

Owner’s Draw Prior to Start-Up is grocery money, shoes for the kids, and that sort of thing. Allow for it.

Finally, something with which you’ll soon be familiar: Contingency is the money you’ve allowed to cover your very human tendency to underestimate the cost of nearly everything and your understandable but probably unrealistic belief that everything will go just the way you planned it.

Now that you have some solid numbers, you can go to the bank and say, “Here’s what I need, so how ’bout letting me have it?” But hold on. Did you think they’d finance you 100 percent? Sorry, but investors (banks or anybody else with half a brain) are going to expect you to risk your own money first, up to reasonable limits. That’s called owner’s equity. If you were to work entirely off other people’s money, you could just walk away if things started going bad, couldn’t you? Investors know that. They want your neck on the block along with theirs; otherwise they won’t play. So that means you’ll have to put up at least some of this money. You don’t need to sell the house, but you may be asked if you’d be willing to take out a second mortgage on it or pull some money out of savings.

So now you need to look at your own financial picture and ask yourself how much you can come up with on your own. If your startup costs are modest, then maybe you don’t need investors after all. If you do, how much money are you going to ask of them? That’s the bottom line.

If you’re buying a business, you need to look at the price of the business plus the carrying costs and contingency. Other than that, the same rules apply.

Sales Projections

Let’s think a minute about your sales projections in general terms. Are you going to remain a one-person operation forever? That’s fine. Are you planning to employ several people after the first year? That’s fine, too. To achieve your goals, you have to know how much you’ll need in sales in order to cover your overhead and profit. In other words, it takes a lot more business to keep ten people working than just one.

What’s the dollar volume of your sales expectations over the first five years? For the one-person maintenance operation, you might be satisfied with $50,000 in sales the first year, operating part time, and $100,000 every year thereafter. This would be a modest goal, and your expectation would be to make a basic living for yourself. These sales figures are the total amount you take in. They include the big four: labor, materials, overhead, and profit. You don’t get to keep the whole $100,000. Sorry.

On the other hand, you might need $350,000 per year to keep a three-person landscaping outfit in business. (Note: Sales per person in landscaping are higher partly because there are a lot more materials used.) Can you realistically expect to achieve that in the first year, or should you make that your third-year goal? In the financial section, you’ll fully justify these projections; for now you need to simply state them.

One more thing about sales: They’ll vary seasonally. In cold climates, winter is the slow season. In hot climates, it may be the opposite. For me, fall is busier than spring because people procrastinate, then panic at the last minute. Summer’s slow because everyone’s on vacation. Ask around and find out what the seasonal sales curve is for your area. You won’t be able to get straight answers from your local competition unless you resort to some very sneaky spy tactics. But guess what? People who are in the business a couple of counties distant from you might tell you a lot because you’re not a potential competitor. Try going to a state gathering of your trade association and buying drinks for a few successful people. Oh, and your vendors can tell you about seasonal sales volumes, too.

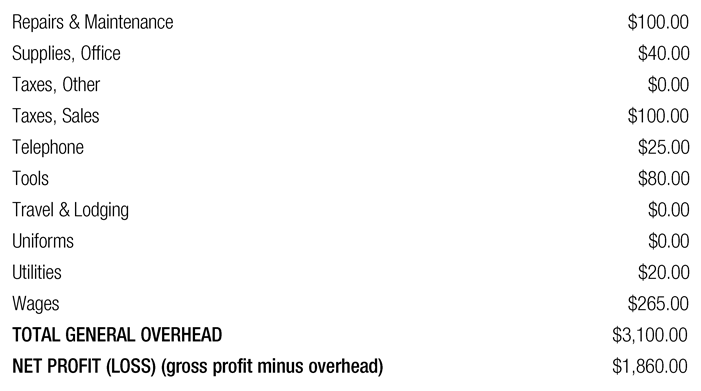

Profit-and-Loss Projections

Also known as an income and expense statement, a profit-and-loss statement (“P&L”) is a list of all your income and expenses for a given period, usually a month or a year. When you’re actually in business, you’ll do these at the end of every month. For now, you’re going to project the same information, on a monthly basis, for the first five years. Simplified just a bit for now, a typical landscaper’s P&L looks like the one later in the chapter.

Let’s look first at the general structure of the P&L. Income is pretty self-explanatory: Whatever checks you get from clients for work you did for them go here, sorted out by whatever categories you choose. In this case, we’re segregating Income into Landscaping, Maintenance, and Other. Cost of Sales is sometimes called Cost of Goods Sold or Variable Expense or Controllable Expense. It’s the stuff—labor and materials—that goes into the actual work you do for your clients, as opposed to overhead. The more work you have, the higher your Cost of Sales. When you buy a bag of fertilizer, or pay a laborer to dig a trench, it gets entered into Cost of Sales under Materials & Supplies.

Now look at what happens: In July, you take in $1 million (let’s dream) of Total Income. Your Total Cost of Sales is $750,000, due to the unpleasant fact that you have to pay your employees, vendors, and a bunch of other people. The quarter-mil you have left over is your Gross Profit. “Gross, indeed,” you might say. “I had a lot of money there for a little while. I could’ve gone to Brazil and lived like a king.” Now you’re getting the idea. Still, you’re an honorable person, so you pay everybody.

Estimated Start-up Costs

Next, there’s the General Overhead. Buy a box of pencils for the office, and it gets entered into General Overhead (aka Fixed Expenses) under Supplies, Office. Simple, right? All the costs of operating your business, the ones that continue even if there’s no work, go here. Let’s say they add up to $200,000. Deduct that from your $250,000 Gross Profit, and you’re left with a Net Profit of $50,000. Not bad for a month’s work. But wait—that’s only a 5 percent profit, which is not considered a great return on your investment and effort. You should feel rotten! To justify your existence, you might want to make at least 10 percent. Next month, you’ll just have to try harder.

Besides, what if your Total General Overhead was $270,000? You would have lost $20,000! Yikes! Time to start looking for a job! (Seriously, you WILL lose money some months. That’s because of the differences between the income cycle and the expense cycle, and it’s not necessarily a sign of problems. Quarterly and annual numbers are more important than monthly ones in determining the success of your operation.)

Well, naturally this is a bit fanciful, because you’ll probably never take in a million bucks in one month, even your best month. Still, I hope you get the idea of how profit and loss works, because understanding this concept thoroughly is important to your success.

Now, let’s suppose you do these projected P&Ls for the first five years. Things look good to you on paper, but any banker can see you’re nuts to put in such optimistic figures. For example, if you project that Cost of Sales will run 10 percent of Total Income, and General Overhead will run another 10 percent, leaving 80 percent for you, you’ll look stupid or conniving or both. There goes your credibility and your loan. So, how do you know what to put in all those little blank spaces? Let’s take it step by step. (See chapter 4 for a discussion of cash versus accrual accounting, another important aspect of financial control. The following examples use a cash basis for the accounting.)

Income. How much work can you realistically do each month and each year? That depends on a lot of factors. Among them are crew size (think of each person as a profit center, capable of generating a certain amount of work per day), productivity, quantity of work available, and selling prices in your area at any given time.

First, consider exactly what kind of work you’ll be doing. Mowing lawns? Great. What’s the going rate in your area? (Hint: Call a couple of competitors and ask them what they charge.) Let’s say that mowing is priced by the square foot. Now, given a certain mower type (ask the manufacturer about the performance of their equipment) and allowing for travel time and nonproductive time like loading up in the morning, how many square feet can you mow in a week? A little arithmetic, and there’s your income.

Some kinds of work are a little harder to figure. For example, suppose you’ll be doing custom landscape carpentry—fences and arbors and decks. Let’s say you and your helper are working a forty-hour week. You figure you’ll bill yourself out at $32 per hour and the helper at $25. Your total labor billings would be $2,280 per week or about $9,500 per month, assuming you could work every week ($2,280 times 50 weeks divided by 12 months. No, there aren’t exactly four weeks in a month, and you’re allowing for two weeks off during the year).

Now, let’s say you’ll sell your materials for an amount equal to your labor. Conveniently, the cost of labor and materials are often about equal for many kinds of construction work. For projections like these, it might be safe to go with this assumption. Better yet, call the lumberyard, get some prices, and figure out how much lumber you can use up in a week. Experience with the work really helps you in estimating these costs.

Remember that you should be marking up most materials at least a little bit—10 percent, minimum. You have a right to make money on materials as well as labor. Some items, such as plants, are quite profitable—you can usually increase the wholesale price (the price you pay the supplier) by 50 to 100 percent and still remain competitive. Others, such as the lumber in this example, are sold to you at maybe a 10 to 20 percent “contractor’s discount” off retail, so there’s not as much profit to be had. How you express these prices depends on whether you’re working on a time-and-materials basis or a lump-sum bid, but either way the markup is still there. Often, the markup on materials is what makes the difference between profit and loss on the job. (Read about bidding in chapter 7.)

Sample Profit-and-Loss Projection Sheet

You’ll have some other expenses, too, such as equipment rental and maybe subcontractor costs. You’ll need to at least recover these costs, and you should make a 20 percent profit on them. So, after figuring out what those costs will be (do some test bids, call subs, etc.), you might decide to add another $2,200 a month to cover them (this is just an example; actual costs will be different for each job you do). Your Total Income would then be $21,200: $9,500 for labor, $9,500 for materials, and $2,200 for equipment and subcontractors plus your markup on those items.

Of course, in the slow season your income will probably drop. That’s why you do P&Ls for each month, then add them up to get the year’s income.

Remember, projecting this stuff is part science and part fine art. Do all your homework, figure things as best you can. Project, don’t just guess. Spend time, examine your assumptions, take it to your accountant, run your numbers by that landscaper you met at the state convention. It’s important that you do this right, because if your assumptions are wrong, you’ll be in for a shock after a year in business. (Tip: Some professional and trade associations offer for sale “time-and-motion studies” that purport to offer realistic information on how long it takes for a typical worker to perform various tasks like planting and mowing. This data can be quite helpful in understanding your costs, since labor is much harder to estimate than materials. But of course take these studies with a grain of salt, because as the car manufacturers say, your mileage may differ.)

Cost of Sales. Next, deduct your anticipated variable costs one-by-one to arrive at a total cost of sales. Remember that these expenses vary directly with the amount and kinds of work you do.

Here’s where you put the actual amounts you pay for labor, materials, and incidental expenses. For instance, the cost of your lumber goes into the Materials & Supplies category. Money you pay employees goes into Labor. Money you pay to subcontractors gets entered into Outside Services.

General Overhead. Under normal business conditions, overhead figures don’t change with the ups and downs of sales. Utility bills, license fees, insurance, and other overhead items are going to be there whether you have a lot of work or none at all. Enter them month-by-month, remembering that some of them will only occur at certain times of the year or will vary throughout the year. For example, your accounting costs will increase markedly at tax time. It’s important that you enter expenses in the months when they actually get paid, because they’ll affect your cash flow then. Figure your advertising budget based on the marketing strategy you developed earlier in the business plan. Depreciation is based on the cost and age of your equipment; ask your accountant for help on this one. Continue the process, entering an amount in each category, for each month. Add it all up, and there’s your General Overhead.

Net Profit (Loss). Let’s hope you’ll show a 10 or 20 percent net profit. Why? Well, recently someone asked me why businesses should show a profit, as if it was some kind of crime against the people. First of all, without a profit, you’re just making wages, and if you’re going to settle for that, well, why not get a job and save yourself all this effort? Second, without profit, there’s no reserve to pay for problems, to cover the replacement of expensive equipment as it wears out, to fund research and development, or to make improvements in service. Profit is also your reward for taking all the risks associated with starting and operating a business. Finally, profit is the earnings you hope to make on the money you and your investors put up to start and carry the business. That seems reasonable, doesn’t it? So, don’t be afraid of honest profit. You’re taking the chances, making the investment, doing the hard work. You’ve got a right to that profit.

By the way, if you’re sharp, you’re wondering where your salary comes from. Good question. The answer is, that depends. When you start, your income will come out of Cost of Sales (“above the line,” businesspeople sometimes say), because you’ll be helping to do the jobs and you should be paying yourself an hourly wage just as if you were an employee. Later, you may abandon the fieldwork and become a full-time manager. Now you’ve moved “below the line” and become a part of overhead. Now your income must come out of owner’s draw or out of profits. Many, many people get to this point and don’t understand that they’ve just added $30,000 or more to their overhead. Fail to account for that money in your bids, and you’ll go broke. Remember to check on this in a few years when you think things are going just swell.

The easiest way to grind through five years of monthly P&Ls is with a computer. Any spreadsheet program can make this task much easier. If you don’t have a computer and can’t borrow one, do it manually, but just do it. (Many public libraries have computers available for public use. Or, you might be able to use the computer lab at a local community college.)

Don’t forget to increase sales by a realistic amount each year to account for anticipated improvements in your business and also to take care of inflation. Naturally, when sales go up, so do expenses. Overhead probably goes up, too, especially if you’re planning to grow. Every time you add a new element to your business, such as an office manager, more insurance, or a storage lot, your overhead takes a sudden large jump. This may cause you to lose money for a few months until the increase in business begins to pay for the added expenses. On the other hand, if you continue to work out of your home and keep your crew size small, maybe your overhead won’t increase much at all.

Play around with the figures, make test assumptions, and see what happens. When you’re satisfied that everything is as accurate and believable as possible and you’re comfortable with the scenario, put it all together in a neat form. Include a brief written explanation for your projections—what your reasoning was behind the major assumptions you’ve made.

The Cash Forecast

The cash forecast (aka the cash-flow projection) is a tool for predicting how much actual cash you’ll have at any given time in the future. It’s a simple way to tally up cash on hand, anticipated income, and anticipated expenses.

Why bother? Because you might be making a great profit on paper but have no money on hand, leading to what business people call a cash-flow crisis. How does this happen? Well, there are many possible scenarios, but often it’s a simple matter of having too much month left over at the end of the money. If you get a big job and have to pay cash up front for materials, and if perhaps the progress payments weren’t structured right, you’ll suddenly be paying out more than you’re taking in. The cash forecast is a way to avoid this unpleasant surprise. It’s a tool you’ll use to operate your business in the black, but you’ll also include it in your business plan. Look at the sample Cash Forecast Sheet on the following page. (Remember, the figures are only for illustrative purposes—don’t use them!)

You can see this isn’t too complicated, but there are a couple of tips that will help you do it right. Where do you get the Cash in Bank figure? The first month, it’s whatever you put into the account. For subsequent months, you simply carry forward the Cash Balance from the previous month. Petty Cash is money set aside in the desk drawer or your pocket for incidental purchases. Anticipated Cash Sales are any amounts you may receive in cash or checks from clients. Anticipated Collections is money received for bills you sent to clients. All Disbursements refers to your total monthly cash outlay—payroll, materials purchased for cash, amounts paid on your charge accounts, office supplies, everything you expect to spend that month. Notice that some of the overhead items, such as Accounting and Insurance, represent a portion of lump sum payments made on an annual or other non-monthly basis; although you may not have to write a check for these items in the month of your Cash Forecast, you should be setting aside the funds from your income every month so that you’ll have the money later when the time finally comes to make the payment.

What if your Cash Balance is a negative number at the end of a month? Well, that means you’re going to run out of money. It’s a signal that you had better make some arrangements for a cash infusion from some source during that time period. As a part of the business plan, those negative numbers prove that you’ll need start-up money and tell you approximately how much. Naturally, your fore-cast is based on educated guesswork, but attention to detail can get you pretty close. You should know by now what your overhead will be, so that’s easy to include in All Disbursements. Cost of Sales is, of course, a little trickier, as is Income (in your P&L projection), but if you remember that your figures represent goals, and if you’re willing to work hard to achieve those goals, you should be fairly accurate.

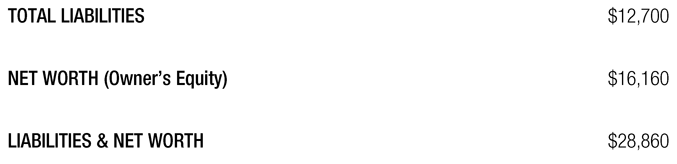

The Balance Sheet

The balance sheet shows your assets, your liabilities, and the difference between the two, called net worth. There’s nothing mysterious about it. Unlike the Profit-and-Loss Projection, the balance sheet looks at the big picture: What’s the final judgment on how you’re doing? The sample Balance Sheet shows what it looks like.

As you can see, this Balance Sheet is simply a list. Fill in the blanks, and you’re done. Current Assets are your liquid assets, ones you’ll normally use within a year. If you have any doubtful Accounts Receivable (ones from deadbeat clients that you think you’ll never get paid for), use Less Allowance for Bad Debts to exclude them. Use Prepaid Expenses for things like insurance that you’ve paid in advance. Inventory for a service business is usually small—maybe just a few bags of fertilizer in the toolshed, but they’re still assets. Fixed Assets are ones you normally don’t liquidate within the year, such as your truck or your lawn mower. Liabilities are similarly separated into Current Liabilities and Long-Term Liabilities. Now, the reason this is called a Balance Sheet is that the Total Assets have to equal Liabilities & Net Worth—that is, the two figures must “balance.” The difference between Assets and Liabilities is Net Worth.

Balance Sheet

These few simple forms have answered all the questions you or an investor might have about your financial projections for the first five years of your operations. True, the actual numbers will be different once you’re in business, but if you’re careful, you won’t be in for any rude surprises.

Description of Accounting Systems

The final step in preparing your financial information is to describe your proposed accounting and bookkeeping systems. (Study chapter 4, then write a simple description of how you’ll handle record keeping.)

What if your projections show a net loss for the first year or two? That’s not improbable, because you’ll be paying for your start-up costs and maybe not having such great sales. That’s when you know you’ve got to find some money to carry you through.

Conveniently, you now have an impressive document. Potential investors can see what your goals are, how much capital you’ll need, and when and how you plan to pay it back.

Alternative Sources of Financing

Banks will probably be happy to lend you money for a piece of new major equipment because they can repossess it pretty easily if you get behind in your payments. They’ll be less likely to give you a loan for general operating expenses. If you can’t get a bank loan for general funds, what do you do to cover your needs?

Well, there are two basic classes of financing: debt and equity. A loan is an example of debt financing: You borrow money and then pay off principal and interest over a period of time. Remember that you have to pay loans back in full and on time. Failing to do so will ruin your credit rating, a major mistake when you’re in business. Guard your good credit with your life, just like your mom and dad told you.

Equity financing is different: In exchange for money, you give up part of the ownership of your company. Generally, you don’t have to pay this money back, but your investor will expect to receive a percentage of the income on a permanent basis. Because you’ll be starting out small, you’ll probably want to use debt financing, but you should know about both. Here are the commonly used alternatives.

Vendor Credit and Progress Payments (Debt)

Fortunately, there are a couple of important methods of financing built right into standard business procedure. One is vendor credit; another is progress payments. They’re linked in an important way. (See chapter 8 to learn more about these topics.) These are the everyday sources of money for your business. Here’s the idea: You buy materials from your vendor on credit, collect progress payments of money that your clients owe you for the work you did, and use it to pay your vendor’s bills. There’s no interest charge if you pay on time. (Related to this is accounts receivable financing, which is sometimes used as a short-term solution to a cash crunch. A bank or other lender advances you a percentage of the value of your good receivables. It’ll cost you, so don’t use this method unless you get into trouble.)

Vehicle Loans (Debt)

If you choose to buy a new truck, you’ll have no problem financing it as long as your personal credit is OK. Using a loan to purchase the vehicle is the most common and least costly way to do this, but you can also lease a vehicle. A lease costs more than a loan and has some other disadvantages, but unlike a purchase, you can usually take possession with very little money out of pocket. (Tip: Buy if you can; lease if you must. And be sure you look carefully at the terms of the lease, particularly what happens at the end of the lease period when you have to turn the vehicle in or buy it.)

Turning Fixed Assets into Cash (Debt)

Take out a second mortgage on your house if you have to. If you have an old high-interest loan, you might consider refinancing, which could lower your monthly payments, freeing up cash that you can put into the business. You may even be able to pull some cash out of your equity. Talk to your lender or to a reputable mortgage broker to find out what your options are. (Tip: Watch out for loans with unrealistic payment requirements; many people have lost their homes because they accumulated too much debt against them.)

Personal Loan (Debt)

If you have good credit and a good relationship with your bank, maybe you can get an unsecured personal loan, which is a loan without any collateral such as a vehicle to back it up. Then there’s the loan (gift?) from Mom and Dad or good old Uncle Harry. As for loans from your boyfriend, girlfriend, best friend, or whatever, do what you want, but you might want to ask a few people who have been there whether that’s such a good idea. It can be a great way to end a relationship. Be careful about drawing your personal associates into your business.

Partnerships (Equity)

You could go into business with a partner, either one who shares in the work or a “silent” partner who is part owner of your business on account of a financial interest but who does not take part in the day-to-day activities of the business. Partners share ownership, investment, and risks. Not all partnerships are 50/50; they can be structured any way you want. Read the section on partnerships and decide whether you really need a partner.

Nonprofessional Investors (Equity)

Mom and Dad, Uncle Harry, a co-worker, a friend, possibly a supplier, or even a client—all could potentially be equity investors in your company. Do you want to share ownership with them? Remember, they’ll be looking over your shoulder all the time. Maybe this is a good idea, maybe not. Before you do this, talk to an accountant, an attorney, and yourself.

Small Business Investment Companies (SBICs) and Similar Investors (Equity)

The government operates or sponsors numerous kinds of small business investment organizations. Call the Small Business Administration for current information or use the Internet: www.sba.gov.

Selling Assets

Do you have idle personal assets such as an extra vehicle, a piece of property, or a coveted antique hubcap collection that you could liquidate, either now or later, if you need them? Look at your entire financial picture, not just your proposed new business.