| 07 | Bidding |

Seldom will anyone offer you a job without wanting to know what it will cost. It’s your responsibility to provide clients with a price before you actually do the work, and that’s what the science of bidding is all about. Your price has to be both attractive to the client and profitable to you. Accurate bidding is one of the keys to your success. Bid too high and you won’t get any work; bid too low and you’ll go broke.

Boiled all the way down to the basics, a bid consists of costs and profit. First you figure what the job is going to cost you, then you add on a fair profit, and you’ve got yourself a bid. The Elements of a Bid outline, which follows, shows the way it looks in detail.

Note: Contingency is an allowance for things you can’t foresee (delays caused by others, price increases, weather conditions, etc.). Some people call it the “fudge factor.” Contingency can also be used to include what I call courtesy padding—a little extra money in the bid so you won’t have to nickel-and-dime the client every time some little change comes up on the job.

Important: Remember that you have to recover all your costs before you can make a profit. Most important, the business never pays for anything; it’s always the client who pays. The client pays for your labor and materials, your overhead, your truck and tools, and (if you make that profit) your house and groceries as well.

How a Bid Differs from an Estimate

A bid is a commitment. When you submit a bid, you are agreeing to do the job for the bid price and the client is counting on you to meet this obligation; if you back out, you can be sued for non-performance. An estimate is a way to let the client know approximately how much a job will cost without making an actual commitment to do the work at that price, or to do it at all. Be clear with clients about whether the figures you submit are an estimate or a bid; write one of those two words in big letters on whatever written material you submit to them, and add clarifying language on estimates stating that they are not bids.

About Rough Estimates

At some point in the early stages of a discussion with a new client, they will inevitably want to know what the project will cost. It’s an awkward moment because there’s nothing concrete to go on—no design, no specifications, nothing but a barren or overgrown mess that everyone is looking forward to turning into a paradise. This puts you in the difficult position of giving prices out of thin air. Yes, you may have a sense of the overall cost, and after years of doing this work you will probably be right. But you have no control over how the project will flesh out in the design stage, and you haven’t had an opportunity to measure, to fully understand the scope of work, or to work up some numbers in a methodical way. So there you are, wanting to answer this most difficult of all questions, and if you’re like most of us, you will say something like, “Well, it’s pretty early to say, but, now don’t quote me on this, but, um, I think it should run between, um, X and X dollars.” You take the bait and you set yourself and your client up for disappointment. That part about not quoting you? The client will never hear that, and later they will get sore because the job cost more than what they remember you said and yes, they will quote the heck out of you and let you know that they think you are not competent or honest or a nice person. Also, they will only hear that first “X,” the low one. It’s human nature. The solution? Tell them you want some time to work up a rough estimate, and then put it in writing with plenty of caveats about it being rough, approximate, preliminary, and probably totally cuckoo in places. Give a wide range of costs, and an explanation that there are a million ways to do the job and time will tell what you end up with and what it will cost. Assure them that you can work within any reasonable budget, adjusting the design so that it fits what the client wants to spend. Meet with them again to present this, to discuss it, and hopefully to win them over as a new client.

Time-and-Materials Jobs

Sometimes a firm bid isn’t appropriate. Some things, such as cleanups or demolition, are difficult to bid fairly. Others, such as small repair jobs, are so trivial that a bid isn’t necessary. That’s when you’ll work on a time-and-materials basis, also known as “T&M.” You do the job, then bill for the actual hours spent on labor (at a profitable rate) and for the materials used (marked up from wholesale to retail or at least to a profitable price). A common variation is called “T&M not to exceed,” in which you place an upper limit on what you’ll charge for the job; this approach is used when the client doesn’t want to write you a blank check.

Elements of a Bid

Costs (money you have to put out to do the job)

Direct: (things that go into the actual job)

Labor

Materials

Subcontractor costs

Equipment costs (both owned and rented)

Fees (dump fees, permits, etc.)

Contingency

Indirect: (things that keep your company running)

General conditions (job costs not part of the actual job)

Overhead (what it costs to run your business)

Profit (money you earn for doing the job)

There are good and bad things about doing business this way. It’s great to know that you’ll get paid for everything you do (unlike a bid, which may turn out not have been high enough to cover costs and profit). When you’ve built up a relationship of mutual trust, both you and your client know that everyone will be treated fairly. Still, some clients will look over your shoulder all day, and when you present your bill, they’ll complain because someone showed up at 8:33 instead of 8:30 a.m.

To be successful with the T&M approach, you have to make your billing policies clear. Let the clients know that you’ll charge for time spent off the site (going to the dump, picking up materials, etc.), and tell them what prices you’ll be charging for labor and materials. Give them an estimate of the total costs, and let them know about anything that might increase those costs. If during the course of the work you find yourself spending more time or needing more materials than you originally estimated, then let the client know that right away. That way there won’t be any nasty surprises for either of you at the end of the job.

Bidding and Contracts Questions and Answers

Q: When should I submit an estimate instead of a bid?

A: You should submit an estimate under the following conditions:

Q: How much detail should I include in a bid?

A: Spell out as much as possible about what you will and won’t do. An incomplete bid creates several problems. First, it doesn’t make clients feel very comfortable. They don’t know exactly what you’ll be doing or what each element costs. They may also feel that you don’t understand what’s involved or that you’ve padded the price. Second, you’re not protected. Clients could (and often will) claim that you said you’d do something that you never intended to do. This can lead to arguments, delays, damage to your reputation, refusal of the client to pay you, and possibly a lawsuit or revocation of your contractor’s license.

Q: When do I need a written contract?

A: Legal requirements vary from state to state. Often a written contract is required if the total price of any one project exceeds $500, or some variation on that. If you are a licensed contractor, learn what is required by law to be included in your contracts; this can be very specific and complex and you must do things precisely or you’ll get stung. Get something in writing before you begin any job, no matter how small it is, even if you only get the client’s signature on a job work order.

Q: Should I have written contracts for my maintenance jobs?

A: It’s not a bad idea. Just as with a landscaping job, you need to include detailed information on what you will and won’t be doing.

Unit-Price Bidding

Suppose you install a lot of sod lawns. There’s no point in going through the whole complicated routine each time you bid a job. Instead, you do it once to set a fair unit price, say $1.50 per square foot, and then you use that price every time you bid a lawn. If conditions are unusual (a long carry into the backyard, extra weed control, difficult soil), you adjust accordingly. If you’re smart, you’ll still cost out every job (see the section on “Job Costing” later in this chapter) to be sure you did OK. If you’re consistently making less than you should at a given unit price, adjust it. You should check your unit prices every few months to be sure you’re still making money.

(Tips: A badly figured unit price will lose you money every time you use it, so do your homework. Don’t just imitate somebody else’s prices; their costs may be different than yours and they may even be losing money. Base your unit prices on your own situation. Don’t use unit prices for everything, just for simple things like plants, lawns, and other routine tasks. Never unit-price bid a large or complex job; go through the regular full bidding process.)

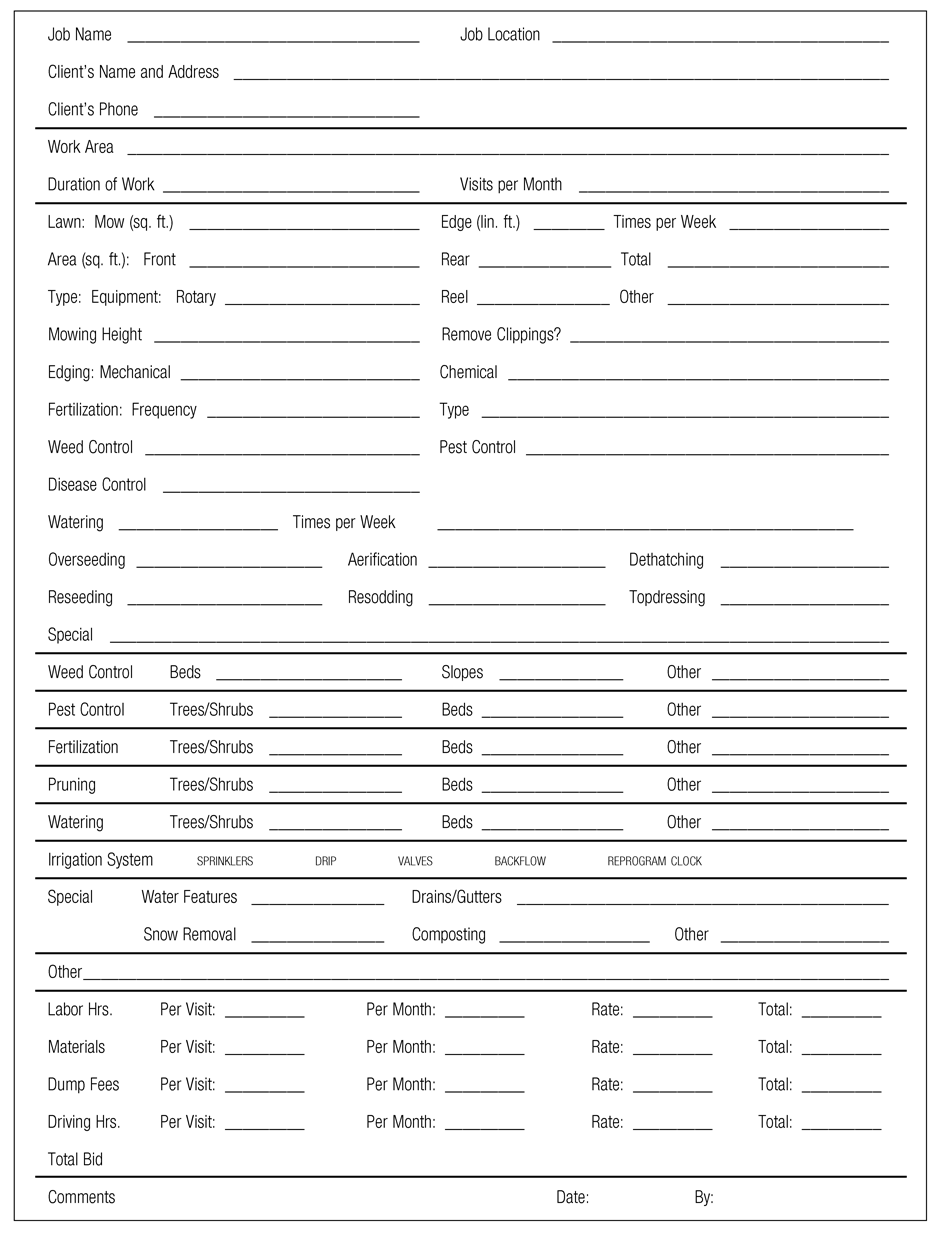

Bidding Maintenance Jobs

Maintenance is mostly labor, so bidding can be somewhat simpler. Otherwise there’s no difference. But remember that you have to live with your bid not just once but every month for at least a year or until you can justify a price increase.

When to Charge for Bids

In most circumstances, charging for estimates or bids is not appropriate. Insurance estimates are an exception. Many times, when landscaping is damaged, the owner will use your free estimate to get money out of the insurance company and then spend it on something else. You’ll probably never get the work, so you can justify charging a modest fee up front for the estimate; you might make it refundable if you get the job.

The same goes for design work. A common con, often tried on inexperienced landscapers, is for the owners to pick your brains for exactly what you’d do to the backyard, and then use your ideas to do the work themselves. That hurts enough that you’ll soon start charging for design work, as you should. Estimates and general ideas are free; specifics should not be. (You could offer to refund part or all of the design fees if you get the work.)

Bidding can be intimidating to newcomers because there are so many little but important details and because there’s so much at stake. There’s nothing worse than getting a job because you were the low bidder and then realizing you will be losing money because of some dumb mistake or oversight (remember that in a formal bidding situation, if you were awarded the job, you are obligated to do it for the price you bid, except in certain special circumstances). But if you take a methodical approach, you’ll find that bidding is not all that complicated. Try following these steps to make the process less overwhelming.

Step One: Do You Really Want This Job?

Some jobs are best left to your competitors. To be successful you need to be selective; don’t try for every job that comes along. Here are some of the questions you’ll learn to ask.

Will this job make me a profit? Did you hear about the landscaper who won $1 million in the lottery? When they asked him what he was going to do, he said he’d probably just keep on doing landscaping until the money was all gone. Well, there’s no point in going to work unless you can make money, so you have to be sure you’re not going up against all the low-ballers in town or that owner who wants a Mercedes for the price of a Ford.

Is this the kind of work I’m good at doing? If the project is beyond your abilities, let it go. To do otherwise is to ask for trouble. It’s OK to stretch yourself with new aspects of a familiar kind of work, but to charge people for work you really have no idea how to do is just wrong.

Is it the right size? Big jobs aren’t for beginners. You won’t be able to bid it right, do it right, or finance it right. Evaluate your available personnel, equipment, sub-contractors, and financial capabilities before you get involved.

Is it in the right location? Don’t take work that’s located 200 miles away. You’ll go crazy commuting and your travel costs will be outrageous. When the job’s done and the client wants you to come out every three days to see if the plants are doing OK, you’ll realize you should have stuck closer to home.

Do I have time for it? Overextending is a major cause of failure. Learn how much work you can handle at one time, and take on only what you have the time to do properly. Although you want to provide service as promptly as possible, clients will wait for you if you have a good reputation. In fact, knowing that you’re busy seems to make people feel better. (I used to have a message on my answering machine that included a comment about my three-to-four-week backlog; I discovered that it made people more eager to get in line to have me do their landscaping. Strange but true.)

Is the client a turkey? Sometimes you look at a job and something just doesn’t feel right, something about the way the guy looks at you or whatever. Maybe you can’t put your finger on it, but after a few bad experiences, you learn that the little voice inside that was telling you to flee was right. Sometimes you’ll take on a job with a potential turkey because things are slow (we’ve all done this); then, sure enough, a week into it you’ll wish you’d never seen the place. (Apologies to actual turkeys, who are more intelligent and certainly more decent than some clients.)

Evaluate potential clients for sincerity (weed out tire-kickers), integrity (don’t fall for that stuff about “give me a good deal on this job, and I can get you lots of work”), ability to pay (the bank does credit checks; why not you?), agreeability (when some people complain about every other contractor or gardener they’ve ever had, you can bet they’ll be talking about you the same way soon enough), and sanity (some people are just too loony to do business with). Apply the same tests to the project landscape architect, general contractor, or anyone else who may have power over you.

Is the project a turkey? Is this a hideous job that you’ll be ashamed to be associated with later? Are there unreasonable risks involved (erosion, soil problems, safety hazards)? If a landscape architect designed it, is it a dreadful design? Are there unreasonable conditions (too little time to bid it or to complete it, outrageous guarantees, etc.)?

How do I get rid of a funky job? If you don’t want it, just say so. True, some people will go ahead and bid sky-high—but that can give you a reputation you don’t want. Others just don’t call such clients back, but that looks bad, too. Just tell them it’s not your kind of project or (if you feel you must lie) that you’re too busy to take it. Thank them for their interest, and move along.

Step Two: The Plans and Specifications

Study the plan drawings and specifications with utmost care because they describe the job and set the standards to which you’ll work. Be sure you have the latest version of the plans plus all addenda and revisions. Ask the landscape architect specifically if this is the case. If you’re doing design/build, you’ll be setting your own standards, which makes things a lot easier.

Many people have gone broke because they missed some little note or detail that cost them everything. For instance, what if you misread the scale of the plans and bid on 4,000 square feet of lawn instead of 16,000? What if you missed the part that said, “Contractor shall obtain and pay for all building permits”? Plans often include lists of plants and other materials; check the quantities shown on the drawings against the materials lists for discrepancies. (Often the specifications state whether the drawings or the lists take precedence in the event of an error.) Read the specifications several times; do the same with detail drawings and any other attachments. Call the landscape architect with any and all questions; the landscape architect is obligated to help you understand his or her intentions.

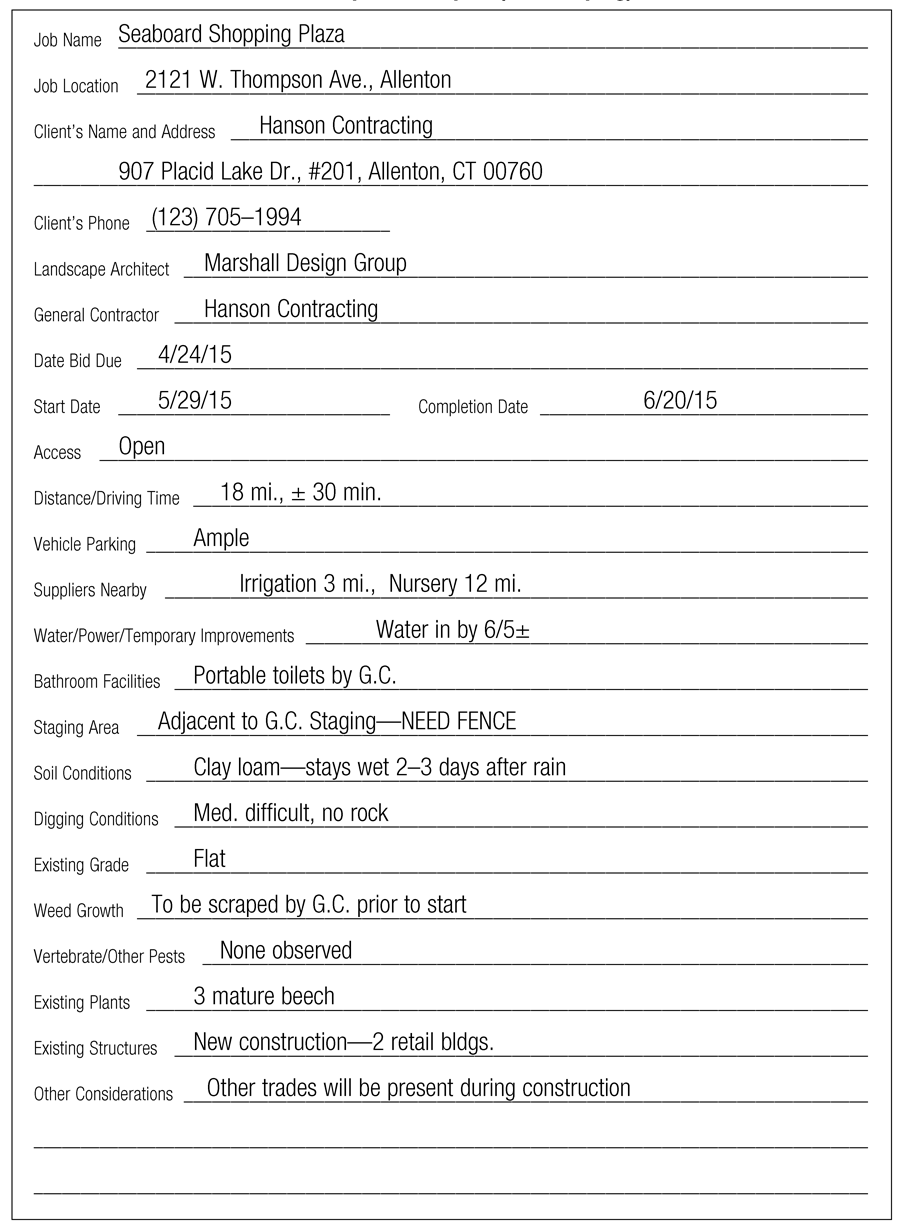

Step Three: The Site Inspection

Anyone who bids on a job without doing a thorough inspection of the site is plain crazy. Site conditions can make a big difference in the cost of the job. Some of the things to look for are soil conditions (Is digging easy or difficult? Are there rocks?), terrain, and existing features (structures, trees and shrubs, weed growth, underground utilities that affect digging, overhead wires that affect equipment operation, accessibility for equipment and materials delivery). Compare the actual dimensions of the site with what’s shown on the plans, because plans are often horribly inaccurate. Look at the finish grade: Is it high or low, indicating potentially expensive earthmoving work? Think about where you’ll park trucks, where the staging area will be, where people will go to the bathroom. Think the job completely through from beginning to end. The Site Inspection Report (Landscaping) will help you with this process. For maintenance work, use the Site Inspection and Bid Worksheet (Maintenance). Both forms appear later in this chapter.

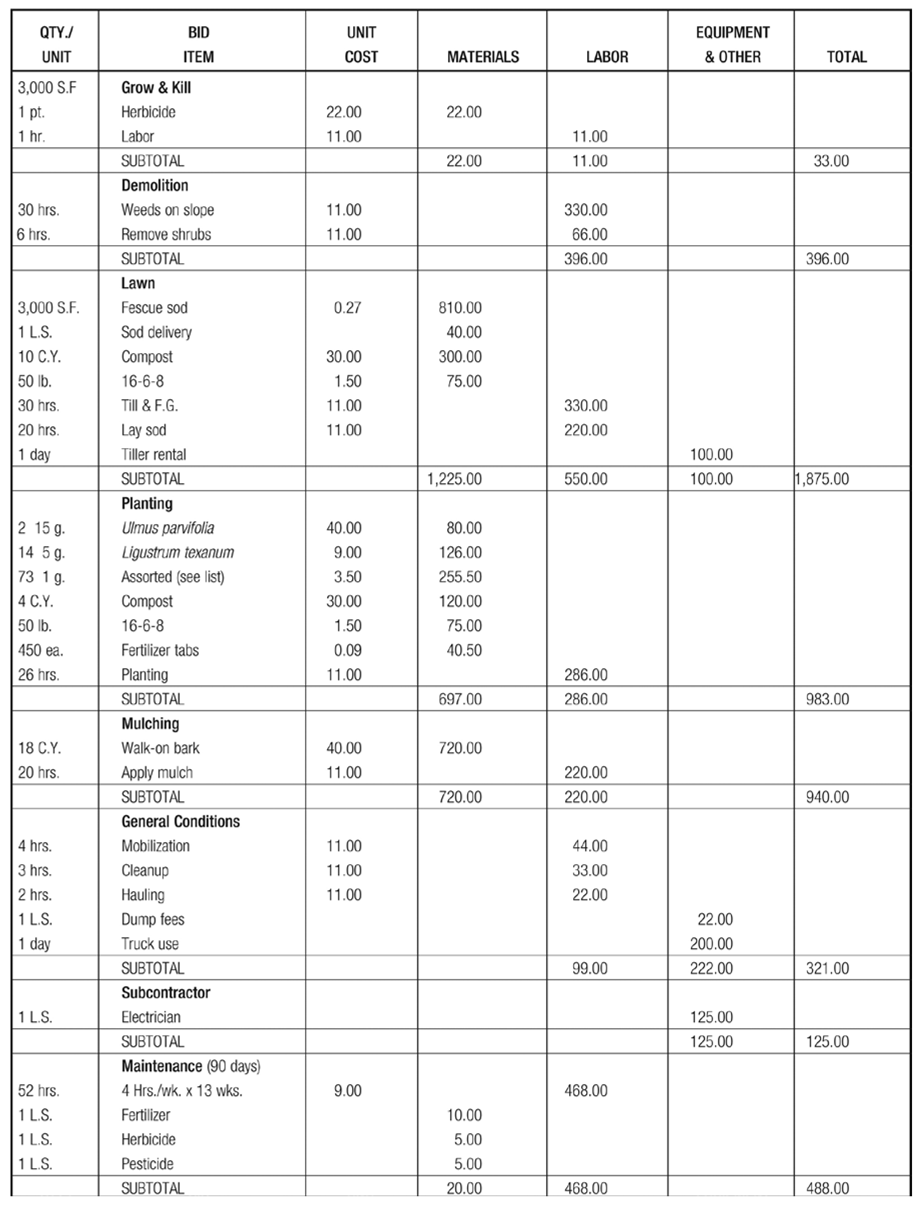

Step Four: The Takeoffs

A takeoff is a list of all the direct costs (materials, labor, equipment, and subcontractors) required to do the job. The takeoff will follow you through the job, serving first as a basis for your bid, later as a shopping list, and finally as a way to do your job costing once the work is completed. Have a look at the Bid Takeoff Worksheet (Landscaping) later in this chapter to see how to organize the information in a usable form. (This process will get easier as you gain more experience. For starters, stick to small, simple jobs.)

Materials

List your materials first. As you go along, mark the plans with a highlighter to make sure you counted everything. Be methodical and careful to get everything. Remember that the plans may show certain items, like plants, but not others, like staking materials or soil amendments. You need to allow for shrinkage, too; for example, when you compact soil, it can shrink up to 30 percent. There’s wastage in almost all materials, so include more of everything. Don’t forget supportive materials like concrete forms that might not be reused. Finally, be sure to include sales tax on a separate line. (Important Tip: The key to successful bidding is building the job in your mind. You’ve got to visualize every act from start to finish: killing the weeds, digging the holes, hauling the mulch up the hill. That way, you’ll get a good idea of the materials, labor, and equipment required, not just a wild guess.) Remember, when you get to doing the actual job, you’ll need what you need, and it’ll cost what it costs. Now’s the time to face it.

Labor

The materials takeoff was the easy part: it’s just counting. Now you’ve got to figure your labor. Labor is usually what makes or breaks you. It’s also a lot harder to estimate than materials because you’re dealing with people.

There’s nothing on the plans that you can count to get your labor costs, so how do you do it? One way is to get a book of time-and-motion studies, often available through trade associations. You’ll find information on how many one-gallon plants a laborer can plant per hour in different soils, how much area a mower can mow per hour, and so forth. Of course, these figures don’t have much to do with your people on this particular job, do they? So use them only as a guide, adjusting for the particular circumstances you face. A better way is to base your labor on what you and your people have done in the past. As you do more jobs, you’ll be able to develop your own time studies as well as adjustment factors for different soil conditions and other contingencies. Include plenty of fudge factor in your labor takeoffs, because you’ll need it. (When I started hiring other people to do work that I had been doing myself, I was shocked to find that they took twice as long to do things as I did. They were doing their best, but they didn’t understand how to work efficiently, so I was faced with training people not only in the technical aspects of the work but also in the art of eliminating wasted motion. For instance, because my mother used to tell me to never go anywhere empty-handed I was accustomed to carrying things with me wherever I went, taking a few plants into the back yard on my way to hauling some refuse from the back yard out to the truck. I watched with growing dismay as my employees would turn that sort of thing into two trips. I would have to show them that they could make things easier for themselves as well as more profitable for me by using their noggins.)

What about your own salary? Well, if you’ll be working on the job, pay yourself an hourly wage. But even if you never leave the office, you need to apportion an appropriate amount of your salary to the job, based on the amount of time you’ll spend on it. Don’t assume you’ll just take your living expenses out of the profit; profit is another matter entirely.

Equipment

Next, list the equipment you’ll need. If you’re going to rent a tractor, figuring the cost is easy: calculate how many days or hours you’ll need the equipment and what the rates are per day or hour, plus delivery charges, taxes, etc. But you will also need to recover costs on your own equipment. One way to do that is to charge what the rental yards would charge you if you had to rent the item. Their business is making money on equipment, so if they don’t know costs, who would? Just remember to deduct your best guessstimate of the profit they include, because you don’t want to add profit on twice (well, you do of course, but it doesn’t help you to be competitive). The other way is to figure actual costs of ownership: Purchase price plus maintenance, less salvage value, divided by the estimated hours of useful life will determine a rate per hour. Naturally, you do this only on trucks and mechanized equipment, not rakes and shovels.

Subcontractors

Include the cost of any subcontracted work you may be hiring out. To do this, you need to get bids from your subs. Allow plenty of time for this; don’t wait until the last minute and expect them to come up with a price. After all, they’ve got to go through the same routine you do. Get them involved right at the start. It’s up to you whether to get more than one sub-bid for each trade. Do it if you need to be low bidder; otherwise, stick with your regular subs and don’t pit them against others. (Tip: Some states don’t allow you to hire subcontractors. In that case, you can get bids from subs but you’ll have to set the deal up so that the client pays the subs directly. Or you can simply have the client handle that portion of the bidding and you will just bid on work that you and your employees will be doing.)

General Conditions

Finally, you’ve got to deal with a category called general conditions. These are costs that don’t become a part of the finished job but have to be paid for anyway. Examples include time spent every day to clean up the site, loading and unloading, travel time, portable toilets, roll-off rubbish bins, moving equipment on and off the job (called mobilization), record drawings, and photos. And what about time spent looking for plants, replacement of plants that die and other warranty work, and dump fees? There are lots of general conditions, and they vary from job to job.

Total Direct Cost

Now add all these factors up to get your total direct cost. That’s what you can expect to pay to get the job done. Oh, and be sure to add one more item: a contingency amount to account for still more unexpected things that will (will) come up. Depending on the project and the bidding situation, two to five percent is prudent. This is guesswork, of course, but like everything else you’ll get better at guessing as you do more and more jobs.

Step Five: Figuring Overhead Recovery

Remember overhead? It’s the cost of running your business (telephone, insurance, gasoline for the trucks, etc.), and it gets paid only if you charge it to the jobs you do. Where else would it come from—the overhead fairy?

You know from your business plan what your overhead should be in the first few years. You also know that your overhead will be low as long as you work out of your home and do things yourself. When you’ve planned in advance for overhead recovery, you’ll know that overhead won’t have to come out of profits because you failed to account for it in your bids. (Tip: You need to recover most of your overhead from your labor, because labor causes more of it in the first place. After all, if you were just selling materials, you wouldn’t need trucks and equipment and tools, you wouldn’t have to pay worker’s compensation insurance, and so forth. So a job that’s labor intensive needs to have more overhead charged to it than one that’s materials intensive.)

Now, divide your projected annual overhead into daily chunks. When you bid a job, figure out how many days it will take and add the overhead amount to the bid price.

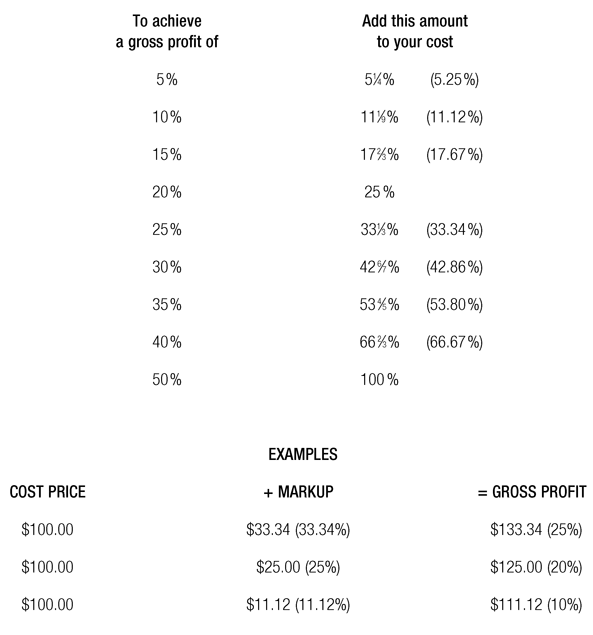

Another approach is to pre-calculate your overhead as a percentage of direct costs. This works better after you’ve been in business a year or two; it will then be more accurate than the previous method. Let’s say your overhead is 15 percent of your direct costs; you mark up the direct costs of the job you’re bidding by 15 percent. (Crucial Warning: Adding on 15 percent doesn’t recover 15 percent! If you have a “markup/markdown” key on your calculator, use it to get the true markup. If you don’t, or if you’re setting up a bid form on a computer spreadsheet, divide your direct costs by the reciprocal of your overhead—85 percent—to arrive at the 15 percent. Or add on 17.67 percent to arrive at the same figure. Play around with this on your calculator until you get the idea. This same principle is true of any markups or markdowns. See the markup chart to better understand how it works.)

Step Six: Adding On Your Profit

Now you know what this job is going to cost you, but you haven’t yet figured out what you’re going to make on it. (If you’re feeling guilty about the prospect of making a profit, go back to chapter 3 and reread the section on net profit/loss.) Remember that profit is your reward for investing in your business and for taking the risks involved in the jobs you do. In fact, the riskier the job, the more profit you should add on.

So, the least profit you should accept is equal to the interest rate the bank would pay you on your savings, plus maybe 2 percent to cover your risk (interest rates are low these days, at least at the time of this writing, so this is usually not enough to compensate you for your efforts). The highest acceptable profit is what will still get you the job and not make you feel like a gouger. When you’ve got twenty years of high-quality work behind you and people are beating down your door, you can probably ask whatever you want for your services. But that doesn’t mean you need to be a lowballer now, just because you’re the new guy. Setting prices too low gives people the idea that you must do crummy work.

Markup Chart

PROFIT POINTERS: Remember that you can’t expect the same profit on a commercial or competitively bid job as you can on a residential job. Smaller jobs should earn more profit than big ones. You may have to lower your profit margin when times are lean and money is tight. Going against lowballers may make it impossible to do the job at any profit. (Here are a few reasons lowballers can bid jobs so low: They may not be licensed and may not pay worker’s comp or other insurance. They might do all the work themselves, dig smaller holes and shallower trenches, use cheaper materials or use less than what’s called for, and do sloppy work. They could be using money from the next job to pay for the last job, or they may not pay their suppliers or their taxes. Some have a rich spouse or parents who support their little hobby of landscaping. Most likely of all, many lowballers are in the process of slowly going broke.)

No one can help you any more than that; your profit margin is your decision. Just remember that good work isn’t cheap and cheap work isn’t good.

Bidding Secrets

Here are some things it takes the average person years to learn:

Front loading (for jobs where you receive progress payments): Get your profits out of the job early on by putting a higher markup on the things you’ll be doing first: demolition, earthwork, and so forth. To do this, you need to do a separate bid sheet for each segment of the job and submit a price for each segment. Prices for early stages of the work will include more of the overhead and profit than later stages. You also need to base your progress payments on completion of specific segments.

Loading “sure thing” items: Sometimes the client will get your bid and start eliminating frills like lighting or water features. By putting most of your profit into the basic portions of the work, you’re sure to make your money. Since they can’t cut out weed control or grading, put more of your profit there.

Rounding off: I once had a sub who would always turn in bids that look like this: $43,167.16. That’s absurd. Round everything up to cover some of your contingency. Turn in round-number bids.

(Tip: If you’re doing bids by hand rather than on a computer, use a printing calculator to run a tape so you can double-check your addition; save the tape with the bid sheets for later reference.)

Step Seven: Checking Your Bid

Double-check everything—your takeoffs, your assumptions, your arithmetic. If you have a partner or someone else who can go over it too, then so much the better. Remember, your livelihood is riding on every bid. Who needs to go to Las Vegas when you risk everything every day?

Look at the Bid Summary Sheet (Landscaping, Lump-Sum Bid) later in this chapter to see how to organize your final bid information.

Alternates

Many times the client will ask for other, possibly cheaper, ways of doing the job. They’re called alternates, and you need to provide a separate bid for each alternate. Many people hate having to bid alternates, but they’re really one of your best selling tools. By getting the client involved in whether to use brick or gravel for the walks, you make it easier for him or her to say yes to the job. Use alternates even when people don’t ask for them—everybody appreciates a choice rather than a take-it-or-leave-it approach. It shows that you’re thinking. Besides, you can make the same profit on the alternate simply by marking it up higher.

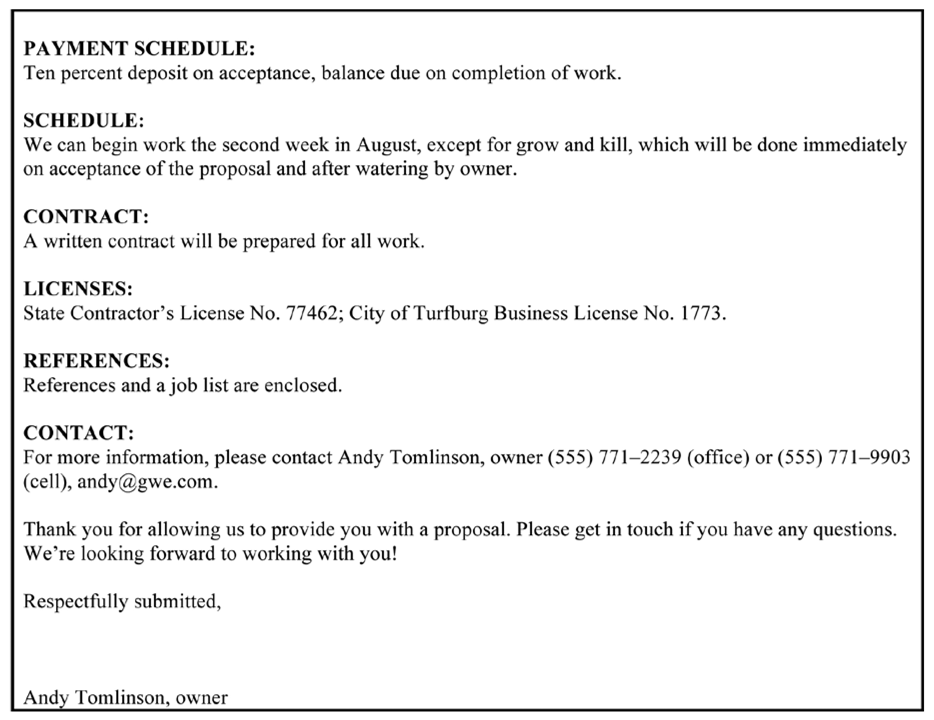

Conditions, Limitations, and Exclusions

Most bids include a section where the contractor clarifies the work beyond what’s on the plans and specifications. This part of the bid document is commonly called Conditions, Limitations, and Exclusions. Often it’s used to tell what you won’t do. For instance: “Painting not included,” or “110-volt supply to irrigation controller to be installed by others,” or “Not responsible for survival of transplanted trees.” Often there’s a rock clause, limiting your liability for unobservable soil conditions and establishing a billing procedure for extra labor required to deal with the problems that might arise from boulders and other junk buried underground.

The Bid Package

On a private residential job, you’ll usually submit your bid directly to the homeowner, or in some cases to the landscape architect. Be sure it’s neatly printed on your letterhead and that all details, exclusions, and other necessary information are included. The bid package is your showroom, so make it professional and attractive. Include the contract (where applicable), a list of jobs you’ve done that the client can drive by and look at, a list of references, your brochure or other sales literature, a credit application if you wish, and a cover letter. Put it all in a nice folder with your business card stuck to the outside where people can see it.

There are a lot of approaches to the format of the bid presentation. The example in the Sample Bidding Forms section that follows shows some of the information you should include; this is a format that works well for me. Remember: Presentation will vary depending on the circumstances.

On a residential job, it’s traditional to meet with the client and go over the bid. Always have a personal meeting with the client; sending a bid through the mail or by email won’t give you the opportunity to explain your pricing and answer any questions the client may have. Generally when you send a bid you never hear from the people again. On a big, competitively bid job, there’s often a formal bid opening that all bidders attend. Whatever the circumstances, this is your moment of truth. Below are a couple of things that can happen at this stage.

So You’re the Low Bidder?

One of the scariest outcomes is to be the low bidder on a competitively bid job, especially if you’re a lot lower than the other bidders. What did you forget? How much is it going to cost you? Is this the end of your career?

Generally speaking, once your bid has been accepted, you’re obligated to do the work. Still, there are certain circumstances under which you can back out or adjust your bid. For example, courts have found that if an error is so obvious that even the client can see that something’s wrong, the bidder can withdraw or rebid. If this ever happens to you, see an attorney at once. (Tip: Always get the bid results of every competitively bid job you bid on so you can see how the other contractors are bidding.)

What If You’re over Budget?

Usually clients have a number in the back of their minds, the price for which they think you ought to do the job. In some cases, the landscape architect has provided them with a cost estimate. Naturally, they won’t tell you what that number is until you’ve submitted your bid. If your number is a lot bigger, you’ve got problems. The client may be shocked. The landscape architect may be embarrassed. They may want to throw you bodily into the street. What do you do?

Let’s say they really want you to do the work, but the price is just too high. You have an opportunity to salvage the situation by telling them what you can do for their price. What can you change or delete? Naturally, they won’t get as much work as the original project (Never lower your bid price to get a job. Never.), but surely you can change something. Start stripping the bid of nonessentials (those low-profit frills like lighting and ponds). Show them on paper how the price drops every time you take something out. Downsizing plants—fifteen gallon to five gallon, fives down to ones—can cut costs in a hurry without changing the nature of the project much. If this doesn’t get you to their price range, suggest doing the work in stages, half now and half in the fall, for example. Go as far as you can without cutting quality or profit (I hope I don’t need to explain why you should never cut either of those things!). Usually this works as long as people’s expectations aren’t wildly off the mark.

When you look at the sample forms in this chapter, remember that there’s no one right way to do bidding; you’ll surely develop your own approach over time. The examples that follow will help you understand the basics. Note: These forms are provided for illustration only. All the figures are fictitious and should not be used in your own bids. (Tip: You may want to provide a line or box on the bottom of each page of any legal documents for clients to put their initials. That’s a standard way to protect yourself against later claims that they “never saw that page.”)

The contract is one of the key documents in your business. Required by law, the contents of the contract will vary, depending on the regulations in your state. You must not get creative with these requirements or you risk losing money or even your contractor’s license. Check with your attorney or the contractors license board to find out what you need. You can make up your own contract (with the help of your attorney) or if you prefer, preprinted forms are sold at contractors’ bookstores and office supply places. Another good source is your state landscape contractors association. Warning: Sometimes the standard forms are incomplete or out of date, because laws change so often. Compare the form to the law before you use it.

If you’re submitting a bid to a general contractor, developer, or landscape architect, they may give you a contract rather than the other way around. Many times these contracts are heavily weighted against you. Read them carefully and negotiate changes in any clauses that are unfair to you. Run the contract by your attorney if you’re not absolutely sure you understand it.

Some people turn in the contract along with the bid, which makes it easy for the client to say yes just by signing on the dotted line. Other times, you turn in the bid and wait for the client to say yes before you send or bring a contract. It’s best to meet with the client to sign the contract. For one thing, she or he may have questions. More important, people often get cold feet at the last moment, so you want to be there to help them make the final decision in your favor.

Logically, this topic belongs at the end of chapter 8 on project management because it’s done at the end of the job, but job costing is so closely allied to bidding that we need to discuss it right now.

Job costing is the flip side of bidding. It’s adding up your actual costs at the end of the job to see whether you made any money. To do it, simply use the bid form to enter actual costs (taken from invoices for materials and equipment, payroll records, and subcontractor billings) where before you entered projected costs. It’s a simple and absolutely necessary procedure. Force yourself if you need to, but do job costing on all your jobs. Then adjust future bids to account for what you’ve learned.

Site Inspection Report (Landscaping)

Site Inspection and Bid Worksheet (Maintenance)

Bid Takeoff Worksheet (Landscaping)

Bid Summary Sheet (Landscaping, Lump-Sum Bid)

Bid Presentation (Landscaping)

To get the job, you have to do more than provide a good price. In fact, price is often of less concern to potential clients than other things. As my old marketing guru used to say, you never sell your product or service; you sell the benefits and advantages for the buyer. To get the job, you have to convince the prospective clients that they will get what they want, whatever that is. Some want the beauty of a new garden; others want the convenience of low-maintenance plantings or an automatic sprinkler system. Some are looking for improved resale value or status or better relations with their spouses. And everyone is interested in hiring a capable, friendly, honest company. To get potential clients to do business with you, you have to figure out what they want, and then prove you can give it to them. Do that and you’ve got the job; fail and you’re down the road, no matter how low your price is.

The idea of “selling” is disagreeable to many people, but we actually sell ourselves every day in many ways to many kinds of people for many reasons. Selling your services is nothing more than the following perfectly honorable set of actions:

1. Find out what the client wants.

2. Figure out how to provide it.

3. Tell (and show) the client what you propose, stressing benefits and advantages.

4. Answer any questions the client has.

5. Overcome any objections the client has.

6. Share your enthusiasm for the project.

7. Close the sale.

Tips on Making the Selling Process Pleasant and Effective

Never mail, fax, or email a bid. Nine times out of ten, when you send people a bid rather than meeting with them, you never hear from them again. Always set up a meeting so you can go through the seven steps of selling (above).

Relax. Your life doesn’t depend on this job. Take it easy, be yourself, and let the process happen naturally.

Talk people’s language. If the client is an artist, talk about how beautiful the garden will be when you’re done with it. If the client is an accountant, talk about the cost-effectiveness of your proposal. Be more formal with formal people and more casual with casual people, but never lose your professionalism. Don’t swear just because the client does, for example.

Dress well. Set your appointments for the morning, before you’ve had a chance to get dirty, or at the end of the day when you can go home and clean up first. Nobody expects you to arrive in a three-piece suit, but they’d just as soon you didn’t track mud from your last job all over their carpet.

Don’t bad-mouth the competition. It’s tempting to tell stories about how lousy your competitors are. Don’t do it. It makes you look bad, and besides, you might get sued for slander. If you know that the client is looking for other bids, give the names of a couple of the best (and hopefully most expensive) competitors. That way you’ll be bidding against qualified people, not hacks. You might even tell these competitors you’ve given out their names and ask them to do the same for you in the future. It sure is nice to be able to choose whom you’re bidding against.

Listen. You can learn so much by paying attention to what the client says. Don’t just walk in and do your song and dance. By being attentive, you make the client confident that you care about him or her.

Show. Bring photos of your other jobs (a photo portfolio on a tablet is great for this). Walk clients through their yard and paint a word picture of what it will look like when you’re done. Make them see the hammock under the trees, next to the new native meadow, and themselves lying there with a cold drink and nothing to do all afternoon.

Never say no. No is the worst word in the English language when you’re trying to sell someone something. When they ask, “Does this plant flower all year?” say, “It flowers from March through October,” not “Well, no, actually it doesn’t.” Who wants to hear “no”?

Be flexible. Remember, you’re there to meet the needs of the clients. If they want something, figure out how you can get it to them.

Watch for closing signals. People act differently as soon as they’ve made up their minds. Here are examples of signs that you should stop talking, answer any specific questions, and then try to close the sale:

KINDS OF QUESTIONS THEY’LL ASK

BODY LANGUAGE

Selling isn’t about bullying people into buying something; it’s about educating them and presenting yourself and your company well. Remember, every good business deal is a win-win situation. The client gets a landscape (or care of a landscape); you get a job.

Closing the Sale

Lots of books are written on how to close a sale. There are dozens of manipulative closing techniques, most of which you won’t need if you’ve done a good job so far. To me, the only dignified close is to simply say something like, “So, shall we go to work, then?” Just give them the opportunity to say yes to your proposal. You don’t have to act like a stereotypical used-car salesman.

After they say yes, try something like this: “Great! Well, I’ll order the plants in the morning so they’ll be here on time. Listen, I’m really excited about this job. It’s going to be beautiful! Thanks for letting me go to work for you. Here’s my cell phone number in case you can’t get me in the office; call me any time you need anything. I’ll call you Friday to let you know what day next week we’ll start. Now if you’ll just sign here, we’ll be all set.” (Tip: In some cases, you have to offer clients a Three-Day Right of Rescission, giving them three days after they’ve signed the contract to back out of the deal. In most cases it will be wise to not start work or order materials until that waiting period has passed.)

What if they say they want to think about it? There are numerous variations on this: “I’ll have to talk it over with my wife.” “I’ve got to ask my business partner.” “We’re still waiting to hear from one other bidder.” Books on the art of selling will tell you that you’re losing the sale at this point, and it’s time to dig in your heels, ask what you could do to sign them up right now, offer them extras, do any desperate and ungracious thing to close the sale on the spot. I’ve never been able to make myself do this. I suggest you remind them of a few of the benefits that you’ve mentioned and, if you’re so inclined, throw in a couple of new ones for good measure. Don’t give them a long spiel, just make one more try, then thank them, ask them when they’ll be making a decision (so you can call them for an answer), and leave.

Call back in a few days to see whether they’ve made up their minds. If you thought up something else that you could offer to help close the sale, offer it. And accept the fact that you’re not going to get all the jobs you bid. In my experience, a capture ratio of 50 percent is decent, though you can do better under some circumstances.

Good luck!