CHAPTER 1

Paris, October 1881

Philippe pushed his way through the other students—all of them older and most of them much taller. Attending a speech given by “Le Grand Français” was an opportunity he couldn’t miss; he had waited years to meet him and didn’t know if he’d ever again get the chance.

The doors would be closing any moment and he hadn’t gotten in yet, so he quickened his pace as much as possible in his constricting blue uniform, worn by all the students at the prestigious Polytechnic School. To have been accepted by the military institution on a scholarship two years earlier, at nineteen years old, was a great source of pride for Philippe. Statesmen, philosophers, scientists, and other exemplary countrymen had graduated from the institution and it was there, at the Polytechnic School, where he too should be educated.

On this visit, Ferdinand de Lesseps would reveal to the teachers and student body the findings of his recent expedition to Panama, which had been chosen by several countries as the location for construction of the interoceanic canal during the Universal Congress in Paris which took place two years earlier.

Being so near de Lesseps filled Philippe with emotion difficult to describe. He could still remember a time when he was a child and an engineer who had worked with de Lesseps in Egypt on the construction of the Suez Canal had come to his home. During the visit, Philippe had been so excited by the engineer’s story, he announced to his mother that one day he too would build canals around the world. “You’re too young for Suez, but you can still build Panama,” his mother had said, and the boy never forgot those words.

Making his way through the crowd, Philippe held on tight to the card that identified him as a special guest of General Pourrat, his sponsor at the “X,” as the Polytechnic School was more popularly known. To be left out of the lecture and miss the opportunity to see and hear “Le Grand Français” was unthinkable. Just then, barely two meters from the entrance, a guard announced that the auditorium was full and that no one else would be permitted inside. People begged and pleaded, and someone tried to force their way through the closing doors.

What he lacked in height and build, he made up for with his strong character and overpowering gaze. “I am a guest of General Pourrat, let me in!” Philippe said, showing his invite to the guard. Once inside, he managed to find an empty seat at the front of the auditorium, just meters from where de Lesseps would be speaking.

If “Le Grand Français” had been able to build the Suez Canal, he would, without a doubt, be successful in the Caribbean, from where he had just returned. Although everyone had read the reports about his expedition, there was great fascination in getting to listen to the story, directly from de Lesseps’ own mouth.

Next to the podium was a strange wooden and metal apparatus pointed toward a piece of white fabric at the front of the auditorium. “A magic lantern! Surely they are going to show us pictures of the Colombian expedition. Excellent!” Philippe thought to himself.

Amid the applause, Philippe heard the doors close and as he turned to his right, he could see Ferdinand de Lesseps heading toward the podium. He wore his thick white hair combed to the left. In spite of his 75 years, his strong and energetic stride was that of a man thirty years younger. His black double-breasted suit and matching tie beneath the collar of his bulging white shirt, gave an air of undeniable elegance.

But the famous mustache with waxed tips pointing upward caught Philippe’s attention more than anything else. As he watched de Lesseps smoothly make his way to the front of the auditorium, Philippe tried to twist the tips of his own modest mustache in the same fashion.

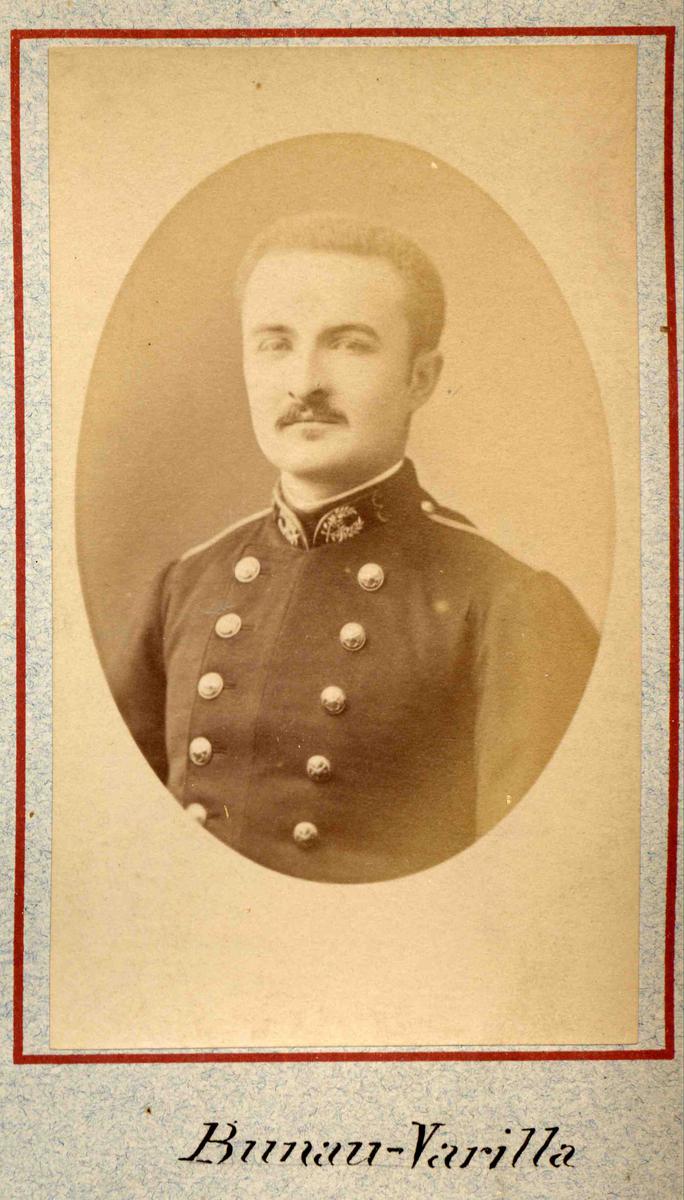

Philippe Bunau-Varilla’s graduation photo from the Polytechnic School

Courtesy of the Polytechnic School; © Ecole Polytechnique.

Ferdinand de Lesseps approached the podium and the auditorium fell silent, anxiously awaiting his lecture. Meanwhile, “Le Grand Français” was clearly satisfied by his observation of the students and professors. Even though he was looking out over the entire auditorium, Philippe swore that he was the intended recipient of his idol’s famous smile.

After welcoming all those in attendance and extending his thanks for having been invited, de Lesseps got right to the point: “For centuries, the civilized nations of the world have wanted to build an interoceanic canal in Central America. The first to suggest building it in the Colombian province of Panama was the Spanish explorer, Álvaro de Cerón in 1517.

“Hundreds of years later, Alexander von Humboldt proposed nine possible routes for the interoceanic canal, and later chose Panama as the best place for construction. And two years ago, the Universal Congress took place here in Paris, and delegates from 36 countries also determined that the Panamanian route is indeed the best.

“A centuries-old Grand Idea that we are now able to put into action. French scientific advances and modern engineering allow us to embark on projects that, in decades past, would have been impossible even to imagine. The proof is in Egypt…”

At this moment, de Lesseps’ assistant turned on the magic lantern and, to the audience’s surprise, an image of the Suez Canal was projected behind the podium. The auditorium erupted with delight. Someone from the back shouted, “Long live ‘Le Grand Français’! Long live the Suez Canal!” and many others joined in.

De Lesseps smiled and gestured for the crowd to be quiet, “The Suez Canal, which was built in large part by students from this very school, has linked Asia and Europe, facilitating commerce and benefitting millions of people. And now, just as I did 21 years ago, I’ve come to invite the best engineers in the world to join me in this new and exciting venture: the interoceanic canal in the Colombian province of Panama!”

The magic lantern now projected a map of Panama, with the proposed route clearly marked. The auditorium was ecstatic. Someone screamed, “We’re going to Panama! We’ll build the canal!” And he was seconded by a professor who sang out the Polytechnic School’s motto, “For country, science, and honor!”

When it quieted down, de Lesseps continued in a more serious tone, “Recently I visited Panama; I was accompanied by our international technical committee and our objective was to inspect the route in which the canal will be built, as required by the treaty with the Colombian government.”

The auditorium had fallen completely silent.

“We arrived on December 30th, on the steamship Lafayette. On the Bahía de Limón, we were received with a warm welcome from the Panamanian people, who were happy that the canal was finally going to be built.” Then he added, with a mischievous smile, “In fact, the local government representative, Mr. Céspedes, jokingly asked why it had taken the French so long to decide to build the canal there. Let us bring peace and prosperity to the people who have welcomed us with open arms!

“Furthermore, as my son Charles said, that part of Colombia is the most beautiful place in the world. And the climate, the climate is perfect: it’s the land of eternal spring.” Someone seated behind Philippe murmured, “Obviously, if he visited the Caribbean at the beginning of summer, I imagine the weather would have been fantastic!”

Without waiting for the initial applause to end, de Lesseps continued, “But, getting back to the purpose of our visit, I have to tell you that after several weeks of personally inspecting the proposed route of construction for the canal, we came to several very important conclusions.”

De Lesseps made himself comfortable at the podium, stroking his upward pointing mustache with his right index finger and thumb, and watched with satisfaction as the entire auditorium leaned forward to better hear him, “The first is that, compared to the construction of the Suez Canal, excavating the Panama Canal will be much easier.”

Various expressions of surprise could be heard throughout the crowd.

“To start, the distance between the oceans is very short; in fact, it’s similar to the distance between Paris and Fontainbleau. According to Abel Couvrex, Jr., we will have to utilize the same excavation techniques that were used in Egypt because the terrain is very similar. So, the experience we gained in Suez will greatly benefit us in Panama.”

De Lesseps continued, “We’ve also concluded that the construction will take only eight years, and not twelve, as we had initially thought. This reduction in time will significantly reduce our construction costs. The funds we had estimated at first will no longer be necessary: we only need half! We’ve already managed to save a great deal and we haven’t even begun!”

Ferdinand de Lesseps had the audience just where he wanted them. “So friends, the construction of the Panama Canal will be more economical and less time-consuming than we originally thought. Those who can, buy stocks when they go on sale! I believe that the Panama Canal Company will be much more profitable than that of the Suez Canal.” Everyone recalled that the value of the Suez Canal Company’s shares had quadrupled since they were issued. If “Le Grand Français” stressed that Panama would also be a good investment, surely it was true.

“But beyond the financial aspect, I believe that we French have been blessed with the responsibility of accomplishing great works which will benefit humanity. The achievement of this Grand Idea, will demonstrate to the world that, in spite of recent difficulties, France will continue to be France!” The audience fell silent, remembering the recent defeat against Germany.

“We have already gotten approval from the Colombian government to begin construction as soon as possible. And there is no time to lose!” de Lesseps exclaimed to the delight of his audience. “It pleases me to tell you that in January of next year, Gastón Blanchet, engineer and general director of our operations, will depart for Panama. He will work with our friends at Couvreux, Hersent & Company, and hopefully, also with many of you.”

He paused again to curl his mustache, and then continued, “Because the Universal Congress chose Panama, the route favored by the French, over the Nicaraguan route, which was selected by the Americans, it is vital that we get the support of the United States. Some might say the Monroe Doctrine requires it. So from Panama, we departed to New York to invite Andrew Carnegie, John Bigelow, J.P. Morgan, and other illustrious Americans to participate as shareholders in the Canal Company. In addition, we offered to put up Company offices in New York. Ours will be a truly international effort,” he concluded, solemnly.

“Therefore, my friends,” he said, growing emotional, affecting the entire auditorium as he spoke slowly and clearly, “we know what we have to do, we know how to do it, and we have the resources necessary to do it. The canal will be built! The canal will be built! Join in this great venture and support France in living the motto of this great institution! For country, science, and honor!” Now the magic lantern showed an illustration of the earth wrapped in the French flag.

The entire auditorium stood up to applaud for several minutes while Ferdinand de Lesseps, with a white handkerchief, wiped away tears of joy brought on by his own speech, before leaving the podium to embrace General Pourrat.

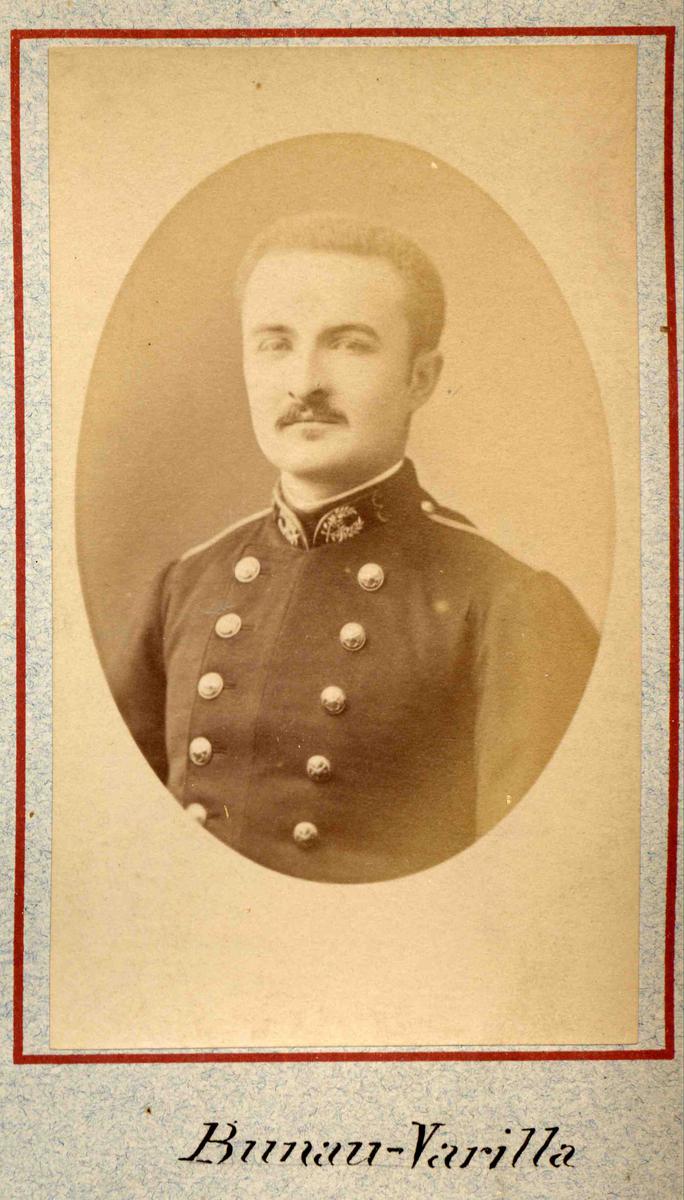

Ferdinand de Lesseps

Public domain image.