CHAPTER 9

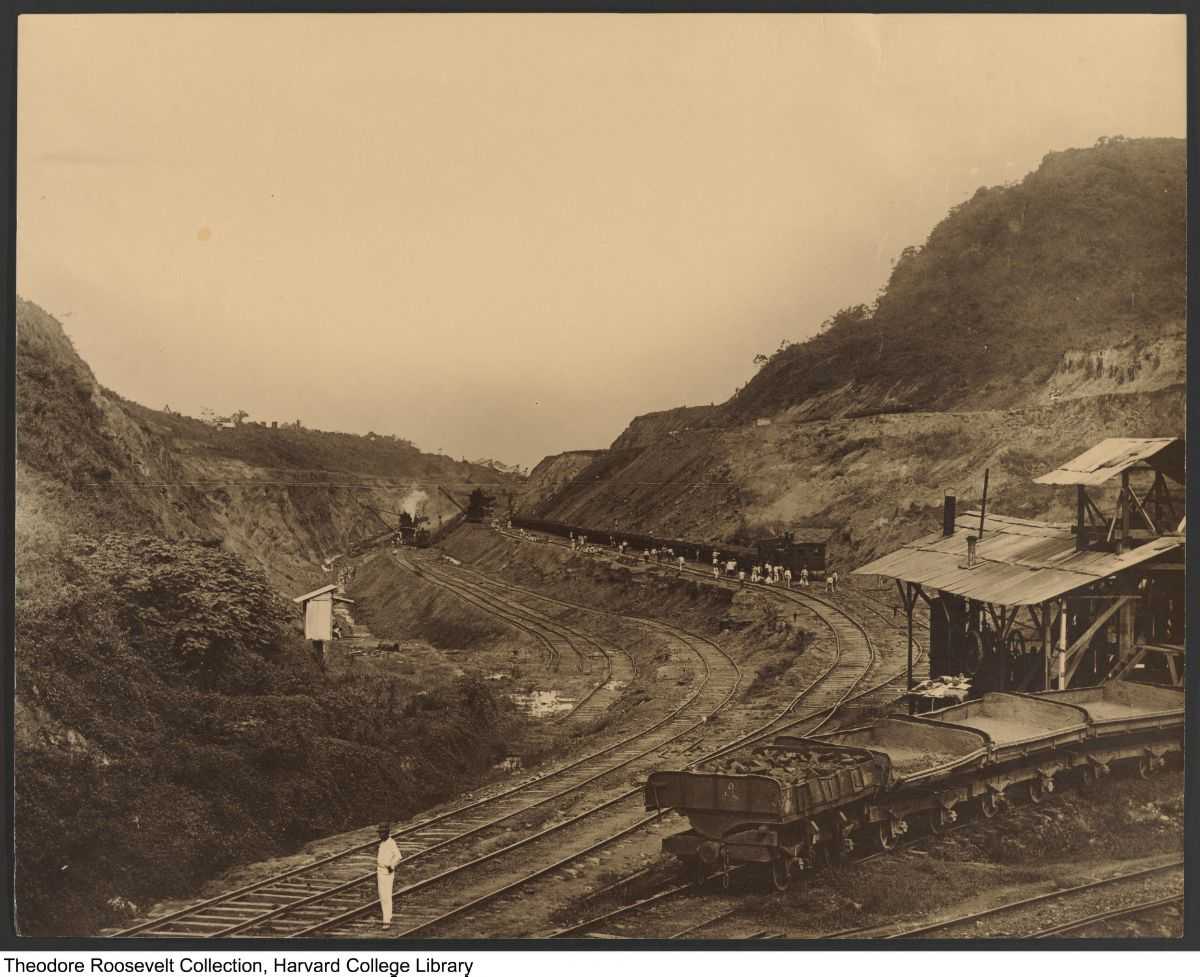

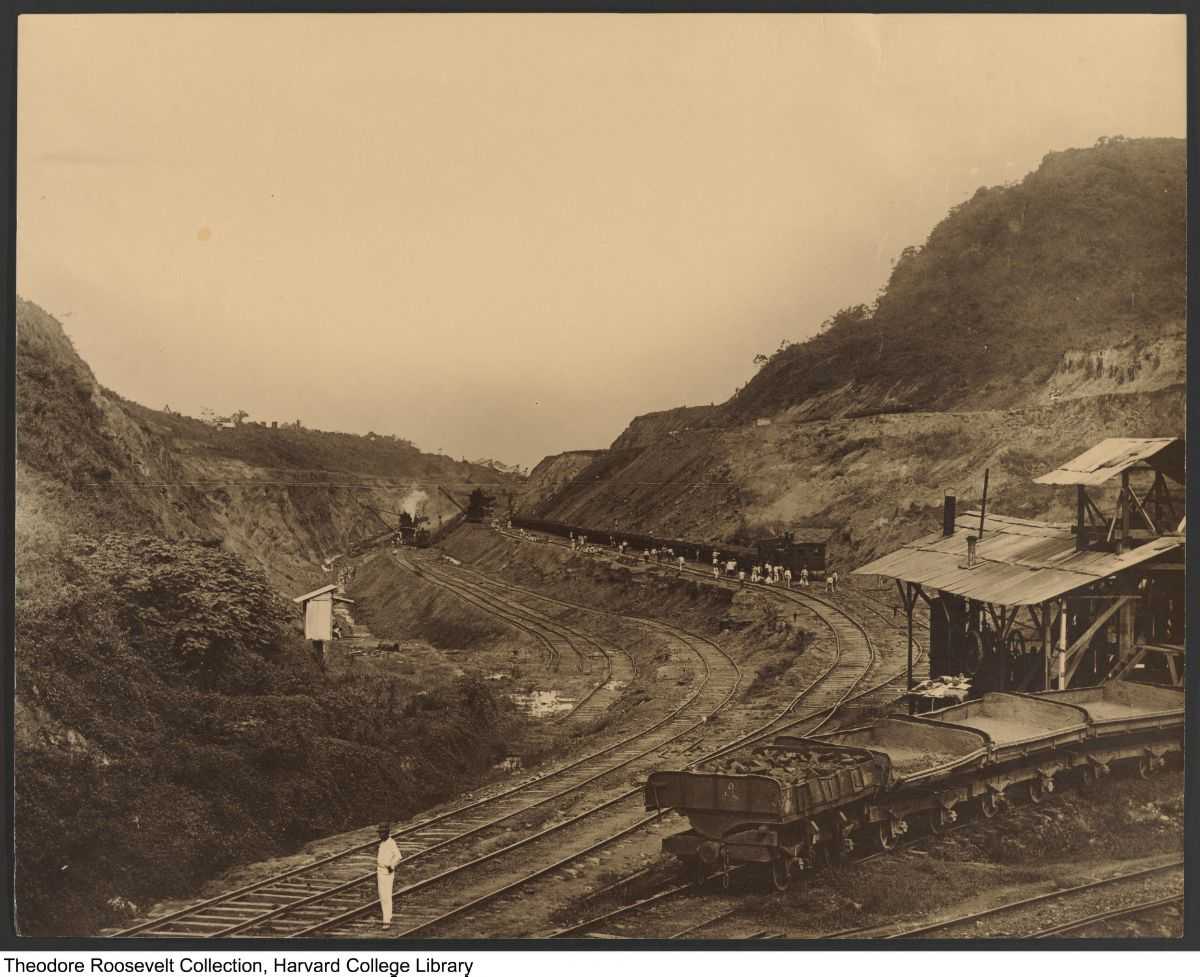

Culebra Cut, January 1887

The first thing Philippe did upon his arrival in Panama, now that he was no longer an employee of the Canal Company but rather, the manager of A.S., was to make sure a home would be built for him on a hill near the excavation. This way, he could more easily supervise his workers and save time not having to come from Panama City, which was where the rest of the contract company managers lived.

There was no time to lose: he had to excavate quickly in order to make money and in turn, pay the loan he’d received. Immediately, Philippe attacked the primary problem on the Culebra Cut: the landslides constantly brought the work to a halt. He had observed with frustration as the contractors became accustomed to hauling the rock and soil from the excavation by train to a nearby hill to be unloaded down the slope. When the discarded materials accumulated to a certain height, the railways extended to the edge of the new terrace so that debris could continue to be thrown downhill. The main problem with this process was that the land on which the rails were built was unstable and when it rained, it would inevitably collapse and take the railway with it. Unable to evacuate the excavation debris, the job couldn’t progress until the rails were repaired.

Philippe had proposed several times that the contractors construct a system of wooden bridges so that the railways would have a solid foundation, but no one had been interested in taking his advice. However, when the new company erected their bridges to evacuate the excavation debris and the rains came, there were no collapses that affected the progress of the job and in a short time A.S. extracted several times more cubic meters of debris than any other contractor on the isthmus.

The other major problem that had to be resolved, according to Philippe, was the employees’ lack of commitment. Most of them were there for the substantial salaries, but from the insignificant progress that had been made, few of them believed the canal would ever actually be finished. A short time after the work had begun, and once he had identified certain workers to use as examples, Philippe fired two supervising engineers and made sure that the rest of the personnel were listening: “I don’t care about your titles or past experience. To accept your salary without believing in the possibility of success is to betray everyone else. Not believing that we will complete the canal is reason enough to fire you!” And with that, all of the workers continued working with a newfound commitment.

And so, with a combination of Philippe’s engineering skills and a strong-handed administration, along with Maurice’s iron-fisted financial management in Paris, A.S. became the most successful contractor on the isthmus. They excavated five times as much as previously had been done, and managed, for the first time, to break through Culebra, a task which had seemed impossible.

Satisfied, Philippe watched as other companies began to copy his methods of excavation, and soon the entire project in Panama was progressing more quickly than ever. It was a time of great success for the Bunau-Varilla brothers, during which they amassed a large fortune which would last them the rest of their lives.

The end of this period of prosperity came when, after slow and painful agony for many small-time French investors, the Canal Company went bankrupt on February 4, 1889. Hundreds of thousands had lost all their savings because they had subscribed to the dream of Ferdinand de Lesseps, who, in a desperate attempt to breathe life into his enterprise, had tried to finance the continuation of the excavation by issuing new lottery bonds that, in the end, no one dared to buy.

Furthermore, some mysterious person sent a telegram to Parisian banks falsely announcing the death of de Lesseps, which drove away several potential investors and put an end to any efforts to revive the company.

When the order was given in Panama to stop the operation on May 15th of that year, A.S. closed their doors and its manager prepared for his return to Paris. For Philippe, it had been thirty productive months; a very satisfying time. He remembered only one bad day during his stay in Panama: the 13th of March, 1888. On that day, a cablegram had arrived from Maurice informing him that his beloved grandmother, Mamie, had passed away. Sitting in the mud during a heavy downpour, Philippe had cried inconsolably. On several occasions when he’d needed his mother but she wasn’t there, Mamie had loved, protected, and cared for him. And when Mamie got sick and needed him, Philippe had been far away, in the middle of the Panamanian jungle.

Courtesy of the Theodore Roosevelt Collection, Harvard College Library

(560.52 1906-061)