CHAPTER 15

Paris, October 1894

Five months had passed since Lemarquis accused A.S. of embezzlement, but still, nothing had been proven. Nevertheless, the brothers were anxious for the process to be over as soon as possible; so when Lemarquis summoned them to propose a settlement, Maurice and Philippe were happy to listen to his offer.

At the time, the liquidator of the Canal Company was preparing to begin a new enterprise: the New Canal Company. The machinery would break down if it was not used, so the objective was to keep the operation running at a minimum level in order to prevent further losses, until a permanent solution could be determined. The liquidator and his advisors had determined that the best possible solution was to sell the new company’s assets, including the Colombian government’s concession which allowed construction of an interoceanic canal in Panama.

As soon as Philippe heard the proposal, he urged Maurice to reject it. “To sell the assets and the rights from the Colombian government is to dishonor France! Absolutely not!”

“Philippe, are you crazy? Lemarquis accused us of stealing money from the Canal Company and you want to reject his plan to recover the investors’ money?” Maurice had a point and Philippe had no other solution but to remain silent until they had reached an agreed upon negotiation with the liquidator.

Lemarquis needed working capital to be able to revive the enterprise and maintain its operation. Once he had summoned all of the contractors accused of embezzlement, he revealed to them where the money was coming from. “Gentlemen, in exchange for dropping all charges against you, we are offering you to become the very first shareholders in the New Canal Company.” At that, the faces of the attendees went white with shock.

“The amount that each individual is to invest will depend on the estimations we are currently disputing. It seems that the most convenient option is for you to accept our proposal and avoid further consequences.” Once they understood how much money they would have to provide, all of them, including Gustave Eiffel, gladly accepted and immediately agreed to the proposition. For some reason, Lemarquis was asking for much less than before. And so, on the 24th of October, 1894, the New Panama Canal Company was founded.

During the first shareholders’ assembly, the new Executive Committee was introduced, which came as a disagreeable surprise to Philippe. First because he hadn’t been invited to participate in the committee, and second, because his former colleague in Panama, Maurice Hutin, had been elected president. “That coward won’t accomplish anything.”

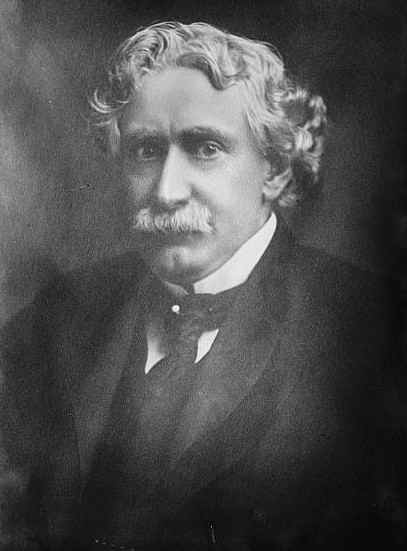

The only novelty was getting to meet William Nelson Cromwell, the lawyer and representative for the Canal Company and for the railroad, which would continue operating as part of the enterprise still based in the United States. “Mr. Cromwell will represent us from his offices in New York and will be in charge of promoting the interests for the New Canal Company in the United States,” Hutin said.

In spite of his prematurely gray hair and a look that betrayed egotism, Cromwell had a youthful face. He’d made himself a millionaire by reorganizing bankrupt businesses and then selling them. His clients included, among other powerful businessmen, J.P. Morgan, and he was known for having initiated an innovative practice known as “business lobbying” in the most prestigious political circles in the United States.

Upon their introduction, Philippe and Cromwell shook hands, one suspicious of the other. They were immediate, however reluctant, allies in the task of reviving the Panama Canal.

Portrait of William Nelson Cromwell.

Photo: Library of Congress, United States.