Chapter 17

‘Be Calm, Be Calm, He is Coming’

The true processe of English policy … is this … keepe the Admiraltie; that we bee Masters of the narrowe see.

Libelle of Englyshe Polycye, 1436

Everything which has gone before should surely have demonstrated that Operation Sealion was an unrealistic proposition in the face of the resources the Royal Navy could concentrate to defeat it, but a little harmless speculation might not be entirely out of place. It must be based on the assumption that Hitler, despite the doubts which he had held about the whole enterprise almost from the outset, had had a flash of inspiration and had given ten days’ notice for Sealion on 11 September 1940. He had, after all, gone against the advice of his military advisors on other occasions in the first year of the War, and had been successful. Perhaps Sealion could have fallen into the same category.

Before this ‘what if’ speculation commences, however, the actual dispositions of the naval forces involved during the third week of September 1940 can quickly be described. The Home Fleet, split as it was between Rosyth and Scapa Flow, has already been detailed, so what follows is an outline of the forces likely to be called upon to meet the Sealion vessels once they were reported. The hard-pressed destroyers and escorts still with Western Approaches Command, already struggling to protect their convoys with inadequate numbers, have not been included, but they too could have been called back if the situation had become critical:

In addition, there were four corvettes and eleven Motor Torpedo Boats with Nore Command, six Motor Gun Boats with Plymouth Command and two MTBs based at Dover. Plymouth, Portsmouth and Dover also contained between them some twenty-five naval minesweepers and 140 minesweeping trawlers, and the numerous small vessels of the Auxiliary Patrol were also available.

To defend the Sealion convoys, Admiral Raeder would have been able to commit five destroyers, supported by four torpedo boat flotillas, based at Cherbourg and Le Havre, and two destroyers and three torpedo boat flotillas based at Ostend, Zeebrugge and Flushing.

Once the go-ahead had been given for Sealion on 10/11 September, the laying of the four mine barriers which must (according to Directive 16) make ‘Both flanks of the Straits of Dover, and the Western Approaches to the Channel on a line from Alderney to Portland … completely inaccessible’ would commence in earnest. As previous descriptions of Royal Navy operations in September have shown, the regular night-time sweeps along the French and Belgian coast can hardly be said to have been disrupted, and the likelihood of producing impenetrable barriers in ten days would have been remote.

By September 1940, the Royal Navy were not only sweeping German fields (there were, after all, 698 minesweepers in service), but were also repairing their own fields. Furthermore, the risk of mines breaking loose and appearing amongst the barge fleets, reducing their unwieldy formation to chaos, must have been of serious concern to Raeder and his staff.

Two days before D-Day for Sealion, the attempt to ‘pin down’ the Royal Navy in the North Sea would begin, when the Herbstreise operation would commence. It was hoped that this force of large vessels, including a number of great German Atlantic liners of pre-war days, sailing from south Norwegian ports in the general direction of the British coast between Aberdeen and Newcastle-upon-Tyne and escorted by the only remaining operational large German warships (Hipper, Nurnberg, Köln and Emden) would in some way draw off the Royal Navy from the South Coast. The force would suggest that a landing was planned, but at dusk retreat to the Skagerrak, and repeat the operation the following day if necessary. Hipper herself would detach and head north to operate in the area of Iceland.

The problem with this operation, however, was that, by the time Herbstreise was due to sail, much of the Home Fleet was at Rosyth, and the expedition would have been desperately vulnerable. As the Royal Navy dispositions had provided substantial anti-invasion forces around the South Coast without any need to call upon the Home Fleet in any event, there was a real possibility that the German Navy could lose its only remaining large warships whilst failing to draw off any of the anti-invasion flotillas in the south.

At almost the same time as Directive 16 was demanding that the Home Fleet be kept away from the invasion area by a diversionary operation, the Admiralty had decided that their heavy ships would not operate in the southern part of the North Sea in any event unless German heavy units did. Unbeknown to the Admiralty, the German Navy did not have any heavy units serviceable at the time, so the reality was that the anti-invasion deployments already in place would have been unaffected.

On the day before D-Day, Lieutenant Commander Bartels at Dunkirk, Lieutenant Commander Lehmann at Ostend, Captain Kleikamp at Calais and Captain Lindenau at Boulogne would be making their final preparations. The vessels from Dunkirk would take a considerable time to assemble in view of the condition of the port and the locks between the inner and outer harbour, and the Ostend portion of this force would have needed to have sailed at noon in order to meet them. In this ‘what if’ scenario, one factor over which the Germans had no control would actually have been in their favour. The weather on the morning of 21 September was suitable for the barge trains, with clouds and intermittent rain, although these conditions would certainly have hindered the Luftwaffe. Indeed, for the eleven days from the 21st, the surf was never above moderate. Had it been so, many of the barges would have been swamped.

All this activity, combined with similar preparations in Calais, Boulogne and Le Havre, would have been impossible to conceal, and the British flotillas at Plymouth, Portsmouth and the Nore would have been alerted. There would have been ample time to make preparations for a night attack, when there would have been no risk of intervention by the Luftwaffe.

Thus, by the time night had fallen on 20 September, the Sealion force would have had at least twenty destroyers, together with three light cruisers, approaching from the west, and a similar number, with perhaps as many as five light cruisers, from Nore Command closing from the east. The old battleship Revenge, from Plymouth, would doubtless not have been involved; her slow speed would have hindered the much faster cruisers and destroyers, and she would have been unsuited for a night action against light forces.

As a member of the smallest and slowest class of Royal Navy battleship, Revenge had received only limited improvements since the end of the First World War, and since October 1939 she had been part of the North Atlantic Escort Force. As Channel Guard battleship, she had undertaken numerous forays into the Atlantic providing heavy cover for convoys including, in December 1939, the first two Canadian troop convoys. She became part of Plymouth Command in August 1940. With her eight 15-inch guns and eight 4-inch high-angle guns, however, she was a powerful asset in the right circumstances, as her bombardment of Cherbourg in October would demonstrate.

Other than the Dora minefield, the only opposition that the Plymouth force might have met would have been the five destroyers and handful of torpedo boats from Cherbourg. Although the advantage gained by the German Navy when B-Dienst had broken the Royal Navy codes had been lost when these were changed in August 1940, these vessels would surely have been despatched to provide some measure of defence for the western flank of Sealion. Quite how much success they would have had is difficult to assess. Even if they had been able to intercept the Plymouth force before it met the larger force from Portsmouth, they would still have been significantly outgunned. Although the modern German destroyers were significantly superior to the older Royal Navy ‘V & W’ Class in speed and firepower, they would have faced in addition the powerful ‘J’ and ‘K’ Class destroyers of the 5th Destroyer Flotilla, which had moved to Plymouth from the Humber earlier in September, and the 6-inch gunfire of two supporting cruisers.

In the past, on numerous night-time minelaying operations, German destroyers had had considerable success, and their high speed had enabled them to avoid action. On this occasion, their speed would be irrelevant – if they were to keep the Royal Navy away from the western flank of the invasion they would have to accept battle. They would probably have inflicted some losses on the Plymouth force, but they would certainly not have stopped it before being overwhelmed.

As the cruisers and destroyers from Plymouth and Portsmouth closed on the western flank, so the powerful forces from Nore Command, mainly based at Sheerness and Harwich, would have been approaching from the north-east. Given the distances involved, and even allowing for the slower speed of the Hunt Class destroyers, there would have been more than enough time to concentrate the whole force in readiness for a night attack. Again, there would have been the Caesar minefield to negotiate, but ships from the Nore had carried out night patrols of the departure ports for Sealion almost constantly for at least the past month, with only one cruiser being damaged. They might have come under air attack before nightfall, but given their freedom to manoeuvre at speed, together with at least the possibility that the Luftwaffe would have had to deal with attacks by Fighter Command, it would have been unlikely in the extreme that the same Luftwaffe which had failed to prevent the Dunkirk evacuation would now overwhelm the Nore force in the few hours before darkness fell.

Surface protection for the eastern flank of Sealion was minimal: two destroyers and a handful of torpedo boats. If these vessels closed they might well have encountered the heavy ships of Nore Command, the Town Class cruisers. There were ten of these vessels in all, of which eight (Birmingham, Newcastle, Glasgow, Sheffield, Southampton, Manchester, Belfast and Edinburgh) were in home waters. Of these, Edinburgh was undergoing a major refit and Belfast was being almost completely rebuilt after mine damage, but three were with Nore Command.

These vessels each carried twelve 6-inch guns and eight 4-inch guns – their power against light surface targets was therefore immense. In the Barents Sea in December 1942, a German destroyer, Friedrich Eckholdt, possibly believing she was approaching the German cruiser Hipper, actually closed on the cruiser Sheffield and was literally blown apart. The captain of Sheffield was later to write: ‘As we swept down on the target she was disintegrating before our eyes.’ The effect of such vessels, together with smaller cruisers and destroyers, sweeping through the lines of small freighters, trawlers, and tugs, all towing barges, can be imagined.

Thus, during the night of 20/21 September, the various Sealion fleets, making their plodding way towards their landing areas, would have found that the impassable mine barriers were nothing of the sort, and the surface escorts totally inadequate. This only left the heavy coastal batteries, which Directive 16 instructed must ‘dominate and protect the entire coastal front area’. It should be possible to estimate how effective they would have been in this hypothetical situation by considering their actual performance in 1940, and the result, from the German point of view, is not encouraging. Some of what follows has already been discussed in the chapter dealing with the coastal gun batteries, but it is worth repeating in this context.

The locations of the various batteries have already been described, but the first test firing seems to have been by the Gris Nez guns on 12 August. Ten days later, the slow eastbound collier convoy CE9 came under fire, and between then and December 1940 some 1,880 rounds were fired at convoys – without success. On 29 September 1940, the elderly monitor Erebus bombarded Calais and came under fire. Erebus dated from 1916, when she had a maximum speed of 12 knots; by 1940, the old ship could probably make no more than eight, but she still escaped unscathed.

Subsequently, on the night of 10/11 October, the battleship Revenge, returning from the bombardment of Cherbourg, was also engaged. Once again, the great guns missed, as they would continue to do for the rest of the War. The conclusion is clear – if the coastal guns could not hit slow-moving convoys or heavy warships, they could hardly be expected to sink or cripple fast-moving cruisers and destroyers approaching the Sealion fleets from both flanks.

Even in the ‘what if’ scenario described above, no great powers of imagination are needed to determine what would have happened when the destroyers and cruisers from Plymouth and Portsmouth encountered the 300 motor boats carrying the assault force from Le Havre to the Brighton–Worthing area, or when the Nore forces reached the 157 tugs, trawlers and small freighters, each towing two barges, heading for the Folkestone area from Rotterdam, Ostend and Calais. The close escort, if indeed it could have been so called, would have consisted of minesweepers and armed motor launches which would also have acted as command ships and guides, but these would have been thinly spread and easily overwhelmed.

The outlook for the towing ships and the towed barges would have been even worse. Presumably, those from the nearer ports would have left harbour in daylight on the 20th (the Rotterdam contingent, however, would been at sea for much longer), and cautiously formed up into large blocks of tugs and barges, three or four columns wide and perhaps as many as thirty tug/barge combinations long. In daylight, they would have been able to see the vessels ahead, astern and around them, and navigation would have been simply a matter of following the combination in front. At this stage, the Luftwaffe would no doubt have been prominent, and the tug/barge crews might have taken some comfort from this. Perhaps, after all, it would be all right.

As night fell, however, anxiety would inevitably rise. The Luftwaffe would go home and navigation would become more difficult. It would be essential to keep the next ahead in sight and to watch out for broken towlines which could suddenly place a motionless barge right ahead. In addition, there was the possibility of one of the adjoining tug/barge combinations losing its way and coming too close, making the risk of collision a very real danger, or even of mines breaking loose from the mine barriers and drifting into the formation.

At some stage, however – earlier for the vessels of the outer fleets (the motor boats heading for Brighton–Beachy Head, or the freighters, tugs, trawlers and their barges heading for Folkestone), later for those heading for Rye–Hastings or for Bexhill–Eastbourne, but equally certainly – searchlights, gunfire and explosions would rip the night apart. The vessels in the outer columns would be first to go – possibly the first anyone would know would be the blinding light of a searchlight from a destroyer, followed by the explosion of 4-inch or 4.7-inch shells. The tug/barge combinations, underpowered, many with inexperienced crews, and in their long columns, would be unable to save themselves, or even to manoeuvre. They would be helpless.

The immediate effect of the attack on the tugs and freighters would probably be twofold. Firstly, barges still attached to their tugs would have been pulled down with them, and secondly other barges, if their tows had parted or been released, would have been left helpless as the formation collapsed into chaos. Quite possibly, smaller barges would have been swamped by the bow waves of destroyers or cruisers passing nearby at high speed, but even the survivors would have been defenceless. By dawn on the 21st, the whole Sealion fleet would have been shattered, but this would not have been the end of the matter.

Given the number of vessels involved, some troops might well have been landed, and as these struggled, with depleted numbers, to establish their bridgeheads, the surviving tugs and steamers would have been required to wait off the beaches until the afternoon of the 21st when they would be expected to re-establish their tow lines and return to their bases to reload with further troops and/or supplies. All this time they would have been under fire from coastal defences and also from Royal Navy warships lying offshore.

This would have been the time when the Luftwaffe would be expected to make a major contribution, providing support for the bridgeheads and sinking or damaging the attacking warships. Quite how this would be achieved has never been made clear – the Luftwaffe had already failed to prevent the Dunkirk evacuation when the only ships present were Allied ones, yet now they would be expected to identify which ships were which among a mass of shipping. In any case, the actual weather for 21 September was ‘cloudy, with intermittent rain’. Similar weather had grounded the Luftwaffe on more than one occasion at Dunkirk.

Most critical of all from the point of view of the German naval planners would have been the tug losses. The plan for the initial assault alone had required 365 tugs/trawlers, and the Navy had only ever managed to assemble 386. Although a surplus of some 700 barges existed to replace losses, there were no reserves of towing vessels. Those which did survive the trauma of the initial crossing, the wait for the tide to turn, and the difficulties of re-establishing their towlines would then face further night crossings, and these would, at least in theory, continue for several weeks. In reality, once the full extent of the losses suffered during the first attack had become clear to the German commanders, both Army and Navy, the sheer impossibility of the whole undertaking would surely have become obvious, and the whole operation would probably have degenerated into a desperate attempt to evacuate the survivors.

Sealion, of course, was never attempted, and no doubt this interpretation of what might have happened to it had it sailed will not meet with the approval of those who believe that air, rather than sea, power would have determined its fate. The fact is, however, that on the only occasion when the Germans attempted a seaborne landing by transporting troops in small boats with a weak surface escort across a sea dominated by the Royal Navy – even though the Luftwaffe had air supremacy – the expedition was utterly destroyed. Although the scale of the operation was by no means comparable to Sealion, the outcome is illuminating, and the action took place north of Crete on 21/22 May 1941, by which time the Luftwaffe had become much more skilled at attacking warships.

In order to support the German paratroop and glider landings on Crete, which took place on 20 May 1941, a force of 2,331 men, with heavy weapons and ammunition, was assembled at Milos in twenty-five small cargo steamers with instructions to reinforce the airborne troops who had captured Maleme. This force, escorted by a small Italian destroyer, and moving at 4 knots, left Milos on the 70-mile voyage early on the morning of the 21st. They were intercepted at 2330 hrs on the 21st by a Royal Navy force of three cruisers (Dido, Orion and Ajax) and three destroyers (Hasty, Hereward and Kimberley), and all but three steamers were sunk, despite a brave defence put up by the escorting destroyer (Lupo), which survived. Many of the troops and crews were subsequently rescued by Italian fast motor boats, but in terms of the battle for Crete the convoy had been annihilated.

In fact, although Crete eventually fell, no German reinforcements arrived by sea, and some 17,000 troops were evacuated by the Royal Navy, which lost three cruisers and eight destroyers during the operation. The main objective of the Royal Navy, the prevention of reinforcements reaching the German airborne troops by sea, was achieved, but as in the Norwegian campaign, the Royal Navy could not exert any significant influence on the land battle. Once again, German air supremacy was the crucial factor on land; Fliegerkorps VIII, transferred from France and still commanded by the same Wolfram von Richtofen who had been so pessimistic about Sealion, consisted of 716 aircraft, including 433 bombers and dive-bombers and 233 fighters.

To oppose these, the Air Officer C-in-C Middle East, Longmore, had at one stage ninety bombers and forty-three fighters in the whole of the Mediterranean theatre of war, including the Western Desert. This was at a time when the RAF had fifty-six squadrons of fighters and fighter-bombers based in the south-east of England, often carrying out multi-squadron fighter sweeps over France!

Much of the above cannot be anything other than speculative, but the only reasonable conclusion that can be drawn is surely that the Sealion operation as conceived by its planners would have resulted in a disaster for the German forces committed to it. Even if the Luftwaffe had been able to maintain air superiority over the Channel, they would not have been able to defend the invasion fleets from the size of force the Royal Navy would have brought to bear against it; and at night, when these fleets would actually have crossed the Channel, they could have done nothing at all. The impenetrable mine barriers and the dominating heavy guns no doubt read well in the Directive, but they would not have protected Sealion from the cruisers, destroyers and smaller vessels of the Royal Navy from Plymouth, Portsmouth and the Nore, and the greatest fear of the German naval planners, of such vessels rampaging through the lanes of transports, would have become a terrible reality.

When all the myths and legends are stripped away, the actual available evidence suggests that the invasion of Britain was not prevented by the machine guns of Fighter Command, or by the inaccurate bombs of Bomber Command, but by the threat of (in the words of Admiral Drax) ‘gunfire and plenty of it’ from the Royal Navy.

Although an attempt to carry out the invasion in September would have been doomed to failure, it is difficult to identify any alternative period when an attack might have succeeded. Certainly, it could not have been later, for the weather in late autumn and winter of 1940, and into 1941 would have made conditions in the Channel impossible for the barges; an earlier attack was never a realistic possibility, as neither the plans nor the shipping existed.

The general assumption in the mythology of 1940 always seems to have been that a successful German landing would automatically have led to a German victory, but in fact, other than in the immediate post-Dunkirk period, the evidence suggests that the resources available to the British Army would have been sufficient to provide significant opposition to the initial assault, especially in view of the problems any German forces which did get ashore would have had in obtaining reinforcements and supplies.

Immediately after the conclusion of the Dunkirk evacuation, on 8 June 1940, the War Office identified British forces available in the United Kingdom as consisting of fifteen infantry divisions and one armoured division. One of the infantry divisions was based in Northern Ireland, and the average strength of each infantry division was 11,000 men of all ranks, or approximately half normal strength. In addition, the 51st Highland Division was still fighting (but was eventually lost) in France, and the 52nd and 1st Canadian Divisions were arriving in Cherbourg as part of a ‘Reconstituted BEF’, which was subsequently withdrawn. The War Office also estimated that it would take around three weeks to reform the troops of the BEF evacuated from France.

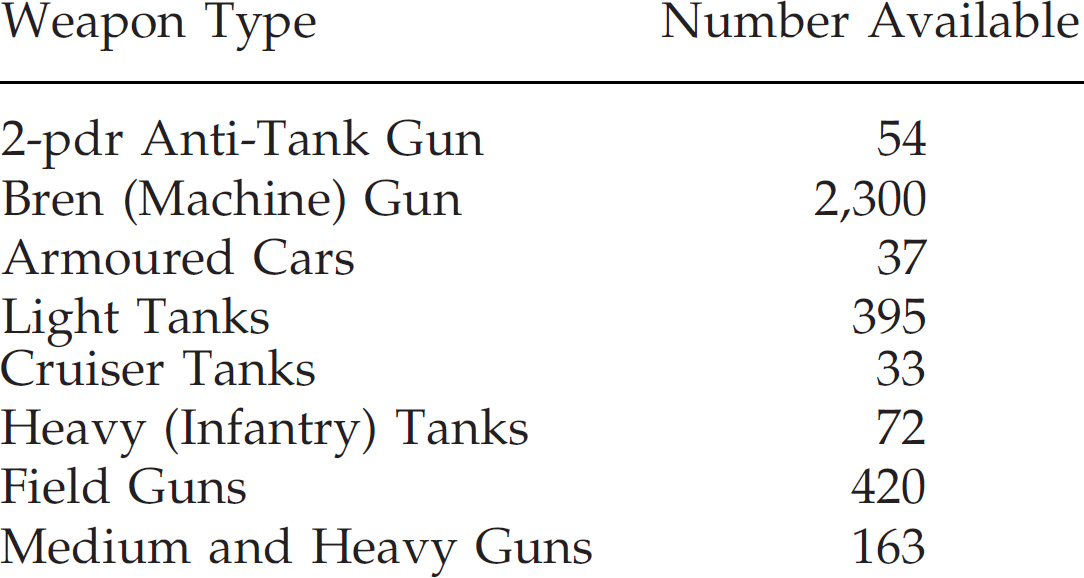

An inventory of the weapons available with which to equip the inexperienced divisions in the United Kingdom (seven of which had had little or no training) revealed quite how desperate the situation was, consisting of:

Five infantry divisions were responsible for the defence of the coast from the Wash to Selsey Bill. These divisions were seriously short of heavy weapons. Each should have had seventy-two field guns, but the total for all five was only 101, two thirds of which dated from the First World War; instead of the total of 240 anti-tank guns which they should have had, the divisions had a grand total of twelve between them.

The only armoured division (the 2nd) was equipped with 180 light tanks only, and was based in Lincolnshire. By 25 June, a mobile reserve had been established to guard against the feared invasion, consisting of 2nd Armoured Division and 43rd Infantry Division based north of the Thames (to respond to an attack on East Anglia), and 1st Canadian Division, two New Zealand Brigades and 1st Armoured Division (equipped with 81 cruiser and 100 light tanks) based near Aldershot to protect the south-east coast.

In the event, although of course this was not known to the British, no matter how lacking in equipment and trained troops the British Army was in June, the fact is that the Germans were in no position to make any sort of invasion attempt. Furthermore, on 9 July the first arms convoys from America arrived, bringing some 200,000 rifles and ammunition which were distributed mainly to Home Guard units, thus releasing standard .303 Lee Enfield rifles to the Regular Army.

By the middle of August, the situation had improved to such an extent that British home defence forces, excluding the Home Guard, consisted of twenty-nine divisions and eight independent brigades, of which six were armoured. Their dispositions were, however, based on the conviction of the Chiefs of Staff that the German invasion, if and when it came, would be aimed at the East Coast and East Anglia. Consequently, only five divisions were placed between Dover and Cornwall, with a further three in reserve, whilst fifteen and a half divisions, with a further two in reserve, were positioned between Cromarty and Dover.

Only when the barge concentrations in the Channel ports became obvious was the threat to the South Coast fully realized, and by mid September the divisions available to meet a South Coast attack had been doubled to sixteen. Impressively, German intelligence (the Abwehr) had estimated that on 17 September Britain had thirty-four and a half divisions, of which twenty were allocated to coastal defence, and fourteen and a half in reserve. The Abwehr had wrongly located some of these forces, but their overall estimate was reasonably accurate. They did, however, believe that it would take some four days for British reserves to counter-attack the bridgeheads, whereas British strategy was based on the number of hours, not days, it would take to undertake counter-attacks.

From 19 July to 21 November 1940, the General Officer Commanding Southern Command was Sir Claude Auchinleck, with Major General B.L. Montgomery as one of his subordinates, in command of V Corps. Auchinleck believed that any German landing should be opposed at the earliest possible opportunity, whereas Montgomery felt that there should be a thin ‘screen’ of light troops on the coast, with the main strength held in reserve, in his own words, ‘poised for counter-attack and for offensive action against the invaders’. This difference of opinion, although not relevant to the main theme of this book, is interesting as it reflects the subsequent conflicts in the German high command towards Operation Overlord, with, in simple terms, Rommel promoting the Auchinleck strategy of coastal defence, and von Rundstedt the Montgomery option of concentrating forces for counter-attack. When planning Overlord, Montgomery had clearly modified his views somewhat, as he assumed that the German policy would have been one of stiff resistance to the initial landings.

Sealion, of course, never took place, but it is clear that, however weak and unprepared the British Army had been in the days immediately after Dunkirk, by the middle of September German troops assaulting the beaches of Southern England would have met stiff opposition, and their need for reinforcement and resupply would have been urgent. Whether reinforcements and supplies could have reached them as they awaited the British counter-attack is, however, quite another matter.

General Gunther Blumentritt, who had been Chief of Staff of Fourth Army from the autumn of 1940, believed, when interviewed after the War, that an attack could have succeeded, observing that ‘We might, had the plans been ready, have crossed to England with strong forces after the Dunkirk operation.’ This does, however, beg the question. The plans were not ready, the strong forces were not available, unless the second phase of the French campaign was delayed, and in any case there were no suitable transport vessels which could be called upon. Senior German Army officers continually underestimated the difficulty of the Channel crossing throughout the planning of Sealion, and the comment suggests that General Blumentritt was still underestimating it after the War!

There can be little doubt that, immediately after Dunkirk, the British Army was in no state to provide much resistance to strong German forces landing on the East or South Coast. As for the Germans, the fact was that never at any time, whether June or September, were they in any position to ship these forces across, unless the Royal Navy could somehow be removed from the equation, and Germany in 1940 lacked the weapons systems to facilitate this removal.