“Have you been doing any thinking about what you’re going to be when you grow up?” asked Ellen.

“No,” said the lion. “Have you?”

—CROCKETT JOHNSON, Ellen’s Lion (1959)

Crockett Johnson was born David Johnson Leisk (pronounced Lisk), in New York City, on 20 October 1906. His grandfather, David Leask, was a carpenter in Lerwick, in Scotland’s Shetland Islands. He and his wife, Jane, ultimately had ten children, all of whom attended school until they were old enough to learn a trade. Their third child and second son, named for his father, was born on 3 August 1865, and by age fifteen, he was an apprentice stationer. By 1890, after a brief career as a journalist, young David had left what he called the “treeless isles” and emigrated to New York, where he found work as a bookkeeper at the Johnson Lumber Company.1

In a department store on Fifty-Ninth Street, David Leisk met Mary Burg, a twenty-eight-year-old saleswoman who as a teenager had emigrated from Hamburg, Germany, to Brooklyn with her parents, tinsmith William Burg, and his wife, Johanna. In October 1905, David and Mary married and moved into a six-story apartment building at 444 East Fifty-Eighth Street in Manhattan, a block west of the East River and a block south of where the Queensboro Bridge (the Fifty-Ninth Street Bridge) was under construction. A year later, Mary gave birth at home to the couple’s first child. The new parents named their son after his father and his place of employment: David Johnson Leisk. When daughter Else joined the family on 27 May 1910, her literature-loving father gave her the middle name George in honor of novelist George Eliot. By 1912, the Leisks had moved out of their Manhattan apartment and into the suburbs—Queens.2

A new borough of New York City, Queens had unpaved streets, no sewers, and more chicken owners than any other borough, though the Board of Health was beginning to crack down on unlicensed livestock. The Leisks lived in Corona on the second floor of a two-story wood-frame house at 2 Ferguson Street (today, 104-11 39th Avenue, next door to the Corona Branch of the Queens Public Library). Young David and Else Leisk loved pets, and their big, gentle father indulged them with cats, dogs, and a bird. The boy often brought home lame animals, many of them rescued from the Leverich Woods, a block west of their home. Dave attended Public School 16, two blocks south of the Leisk home and directly across the street from Linden Park, a 3.5-acre oasis in increasingly urban Corona. In the summer, the park hosted band concerts, and boys fished in Linden Lake; in the winters, the lake offered ice skating.3

David Johnson Leisk and his mother, Mary, n.d. Image courtesy of Smithsonian Institution. Reprinted with the permission of the Estate of Ruth Krauss, Stewart I. Edelstein, Executor. All Rights Reserved.

Dave’s father retained the affinity for the sea that dated back to his childhood in the Shetlands. He built a sailboat in the family’s backyard and took his son sailing on Long Island Sound. On Sundays during Dave’s childhood, his father would frequently row a small boat out into the water, and Dave and Else would swim and play. By 1915, however, sewage emptying into Flushing Bay led the Board of Health to advise against swimming there.4

During the summers—and especially when the winds blew from the east— the Leisks and their neighbors inhaled the pungent smell of garbage, rotting in the heat. They lived four blocks west of the Corona dumps, famously described by F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby (1925) as “a valley of ashes.” Thinking the former Corona Meadows an ideal location for an industrial park, real estate developer Michael Degnon bought them, employing laborers to fill them in with ashes from Manhattan. When the railway cars full of ash came to a stop at the meadows, Fitzgerald wrote, “the ash-grey men swarm[ed] up with leaden spades” to unload them. Although Degnon’s Borough Development Company was supposed to be dumping only clean ashes and “street sweepings” (a euphemism for horse manure), people threw out all kinds of garbage along with their ashes.5

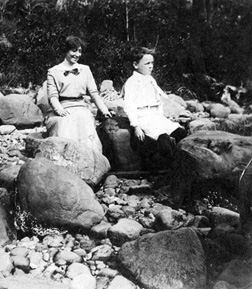

David Leisk, “Kuku Karl and Hesa Nutt Visit the Museum,” Newtown High School Lantern, May 1921.

In September 1915, nine-year-old Dave saw his first strike when the ash-grey men walked out to protest the wages and hours demanded by the Borough Development Company. In October, the company fired the men and hired a new group of workers, but the incident left an impression on young Leisk. In “Kuku Karl and Hesa Nutt Visit the Museum,” one of the first cartoons he drew for his high school newspaper a few years later, one character “saw how big a pyramid is” and “asked where they would have buried the king in case of a brick-layer’s strike!”

To distinguish himself from the other boys named David in the neighborhood, Leisk borrowed a name from a comic strip about frontiersman Davy Crockett, and some friends began to call him Crockett. In 1934, he started signing his work Crockett Johnson, and by 1942, the phone book listed him under that name. After his childhood nickname became his professional name, however, he began using Dave privately. But private and public were closer than he was willing to acknowledge. Crockett Johnson’s works were always a reflection of Dave Leisk. It’s no coincidence that his most famous character, Harold, is also an artist.6

Dave was relentlessly creative. At the Methodist church the Leisks attended, he drew pictures in the margins of the hymnals. At home, he made clay models and sketched famous people both past and present. One summer, when his sister was away, Dave drew a cartoon in which he imagined her adventures, presenting it to her when she returned. He also wrote stories.7

In these and other respects, Dave took after his father. In addition to his weekly pinochle game with the guys from the neighborhood, the elder David Leisk enjoyed reading and writing. His interests ranged widely and included history and poetry, which he wrote as well as read. He also enjoyed singing—at church and at home, with company or without—and composed a few hymns. He submitted a full news story about the 1920 America’s Cup race to his hometown newspaper, the Lerwick Times. Young Dave also inherited his father’s slow, deliberate manner of speaking.8

Mary Leisk was less easygoing than her husband and was stricter with her children, particularly Else. Reflecting the beliefs of the time, she considered her son more important than her daughter. Resentment at such favoritism sometimes strained relations between the children, though at other times, Else and Dave got on well. They played checkers and chess and tossed a football. However, in addition to being a boy and nearly four years Else’s senior, Dave also had a much sharper mind. Asked a simple question, Dave understood the problem so thoroughly that he might not give a straight answer but instead express himself whimsically, wryly, or even sarcastically. When he did, Else thought that he was being condescending. Believing that her mother encouraged such behavior, Else frequently spent time with one of her father’s Johnson Lumber coworkers and his wife, who lived below the Leisk family and had no children of their own.9

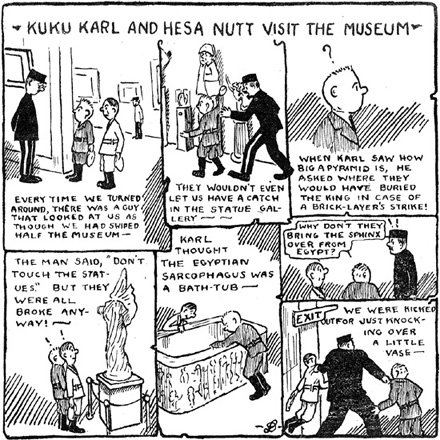

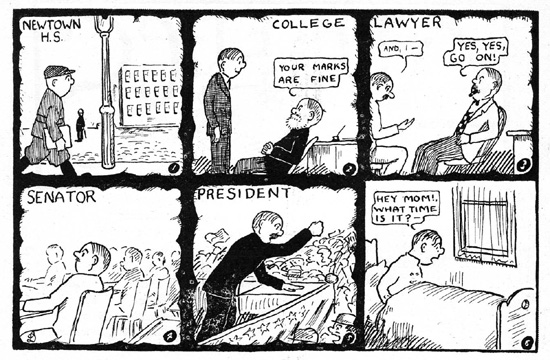

D. J. Leisk, “An Off Day,” Newtown High School Lantern, March 1921.

Dave was intrigued by people who could make things, including his father, who built boats in the backyard, and craftsmen in a borough perpetually under construction. In October 1915, workers began constructing what would be the largest station on the Corona Elevated Railway (now New York City’s Number 7 Train). Opening ceremonies for the two-block-long 104th Street Corona Station, located a block south of the Leisks’ house, were held on 21 April 1917 and featured a band, five hundred girls from Public School 16, two hundred Boy Scouts, and members of the Junior American Guard. The Corona El made the trip from Grand Central Station in just sixteen minutes, bringing Queens closer to Manhattan than ever before.10

For German natives like Mary Leisk, this celebratory moment cloaked the shame and fear inspired by the U.S. declaration of war on Germany two weeks earlier and by increasing anti-German sentiment. In October 1915, former President Theodore Roosevelt had said, “There is no room in this country for hyphenated Americanism…. There is no such thing as a hyphenated American who is a good American. The only man who is a good American is the man who is an American and nothing else.” Although Queens had other immigrant groups (notably Italians and Swedes), prejudice against “hyphenated Americans” was directed largely at Germans. Reflecting the tenor of the times, in the 1915 New York State Census, Mary Leisk listed her birthplace as the United States.11

David Leisk, “Newtown H.S….,” Newtown High School Lantern, May 1921.

With war raging in Europe, some Leisk cousins visited the United States, staying with Mary, David, and their children. When U.S. soldiers bound for Europe visited the young women, the elder David bought them cigarettes. Else remembered her father as “patriotic,” though he generally “didn’t voice any opinion.” On another occasion, the nieces played piano and David sang along, carrying the bass part on “Mother Machree” and “My Bonnie Lies over the Ocean.”12

In the fall of 1920, Dave Leisk, then nearly fourteen, moved on to Newtown High School, where he soon became an artist for the school magazine, the Lantern. The publication’s second issue, which appeared in March 1921, included “An Off Day,” by D. J. Leisk, chronicling the exploits of a round-headed schoolboy identified as “you.” The bottom right corner of the final panel features an overlapping cursive D and L, the sigil that would become his signature for his high school work.

David Leisk, cover for the Newtown High School Lantern, May 1923. Image courtesy of the Queens Borough Public Library, Long Island History Division. Reprinted with the permission of the Estate of Ruth Krauss, Stewart I. Edelstein, Executor. All Rights Reserved.

Newtown High School, Class of 1924. Reproduced Courtesy of the Queens Borough Public Library, Long Island History Division, Frederick J. Weber Photographs.

The cartoon offers a glance at the high expectations faced by Newtown students. A student arriving after 8:45 A.M., as the one in the cartoon does, needed to get a late slip and bring it home for a parent’s signature. Each night, students were expected to spend two to three hours on homework: Those who did not would “probably fail in some subjects.” Newtown offered a general four-year course, a three-year commercial course, a three-year salesmanship course, and four-year courses in both agriculture and music, among other avenues of study. The school encouraged all students to “decide early upon your vocation and choose your college” so that they would meet the entrance requirements: “Don’t make the mistake of supposing that a high-school diploma will admit you to any course in college.” The school offered classes in history (both American and European), economics, mathematics (including algebra and plane geometry), natural and physical science, and German, French, and Spanish. English classes featured works by Wordsworth, Stevenson, Tennyson, Emerson, Shakespeare, Milton, Coleridge, Abraham Lincoln, and George Eliot as well as Canadian poet John McCrae’s “In Flanders Fields” (1915), a patriotic call to arms that had become popular among Allied troops during World War I.13

Dave contributed to the Lantern as both a writer and an illustrator. He drew his first cover for its May 1922 issue: Framed by tree branches, a laughing boy’s head rises above the surface of what may be Linden Lake. His cover for the May 1923 Lantern features a similar drawing, showing a young man who has fallen asleep while fishing by the lake’s edge. If his cartoons are any guide, Dave knew that he was a dreamer but was less sure where those dreams might lead.14

David Johnson Leisk at age seventeen. Reproduced Courtesy of the Queens Borough Public Library, Long Island History Division, Frederick J. Weber Photographs.

Though he took up smoking at a young age, Dave was a natural athlete, with a particular interest in swimming, running, baseball, and football. In his senior year, Dave was a member of Newtown High’s undefeated baseball team, though he seldom took the field. Dave also was a shot-putter on the school’s excellent track team, coming in third in the Queens championships. He played tackle on a football team, but since Newtown High School banned football “for fear of safety of the players,” Dave had to play beyond school grounds.15

On 26 June 1924, David Johnson Leisk joined 148 classmates in graduating from Newtown High School. Though not an ambitious student, he had done well enough on New York State’s Regents exams to earn a scholarship to Cooper Union, in Lower Manhattan. He commuted there for two semesters, taking classes in art, typography, and drawing from plaster casts. By the spring of 1925, however, Dave’s father had died, and at the age of eighteen, he dropped out of school to get a job and support his family.16