Hands are to make things.

—RUTH KRAUSS, A Hole Is to Dig (1952)

In the summer of 1919, eighteen-year-old Ruth Krauss was one of Camp Walden’s oldest campers. Founded three years earlier by New York City principal Blanche Hirsch and teacher Clara Altschul, Camp Walden sought to promote democratic cooperation, to foster a love of nature, and to give girls “a happy and vigorous summer, and ample opportunity for all forms of athletic activity,” including archery, swimming, diving, hiking, basketball, baseball, and tennis.1

Ruth took part, displaying more exuberance than skill and earning the nickname Doggie. In an account of “The First Counselor-Girl Basket-Ball Game” in the summer of 1920, fellow camper Ruth Loebenstein wrote, “Doggie got her periods mixed up, and thought she was in dancing class. She did the wilted flower stunt several times, and Miss King even had to blow the whistle to remind her that she was one of the guards and not one of the garden.” That same summer, Ruth captained one of the teams in a friendly weekend camp sports tournament, leading her team to victory. Though they did keep score, Walden was careful to make its competition as noncompetitive as possible: The teams had to cheer for each other. As Ruth would write in Open House for Butterflies (1960), “I think a race looks prettier when everybody comes in even.”2

Walden’s noncompetitive approach derived from Hirsch and Altschul’s allegiance to the principles of Ethical Culture, a movement that sought to create a more humane society by recognizing that each person is unique and by trying to nurture the development of each person’s talents. Parodying the camp’s ethical philosophy, however, Ruth and her best friend invented a “‘lie cheat and steal’ society based on a whole new set of morals.” The young women also resisted their counselor’s insistence that the campers speak only French in their bunks, and the campers combined care packages from home into secret midnight feasts.3

At three hundred dollars for five weeks, the camp attracted girls from well-to-do families, mostly of German-Jewish backgrounds. Walden offered Ruth many outlets for her creativity. Campers took art classes and wrote and staged plays. At a 1920 Backward Party, participants wore their camp uniforms backward. The 1919 issue of the camp yearbook, Splash, contains the earliest surviving piece of Ruth’s creative work, “The Climb up Washington as Told to Me by Ham.” In it, she relates her conversation with a fellow camper who describes the dangers of climbing Mount Washington while Ruth serves as an attentive audience:

HAM: And, Ruth, if you made one mistake you would have gone over. Imagine!! And every second we saw a sign saying THIS MAN DIED HERE. Oh, it was terrible!! They say the scenery was marvelous, but if I had looked down, I would’ve gone right over. And then we’d see another sign saying: This GIRL DIED HERE. Oh, it was terrible! You would have died!!

ME: Ye Gods!

HAM: I wish you could have been there. It was a wonderful experience. Look at my shoes.—and Mr. Hale slipped once on Suicide Path. We had to crawl along on our hands and knees there and test every stone before we tread on it. And you should have seen the falls.

Ruth’s narrative finds the comedy in ordinary language, picking up on Ham’s frequent repetition of “You would have died” and tendency to describe the experience as simultaneously terrifying and wonderful.4

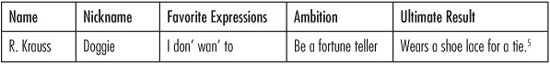

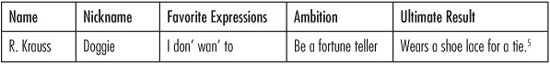

The following summer, Ruth served as entertainment editor for Splash, which featured a chart offering a glimpse of her personality:

In the fall of 1919, after her first summer at Walden, Ruth decided to return to the violin. Her Western High violin teacher, Franz Bornschein, taught at Baltimore’s Peabody Conservatory of Music, which was located only two miles from her home—and she applied to study there. Peabody informed her that she was not yet advanced enough to enroll but was welcome to join the conservatory’s Preparatory Department. After a year of studying harmony, music history, and the violin, Bornschein described her as industrious, intelligent, and musically gifted though with an “odd make up” and “not a systematical worker.” By the end of her second year, he had lost confidence in her. While he still thought she was “instinctively” gifted musically, her work habits were “harum-scarum,” and he wondered if her intelligence might not be “sub-normal.” In her 1920–21 student record, he labeled her as having “an over abundance of temperament; this wildness is difficult to mold into an obedient condition.”6

Ruth Krauss at Camp Walden, Maine, 1920. Image courtesy of Betty Hahn.

Ruth was nonetheless serious about her musical pursuits, and the following year, she chose a different violin teacher, Frank Gittelson. He was younger and a better violinist than Bornschein, had a sense of humor, and was more sympathetic to Ruth’s efforts. Although he found her intelligence “very erratic,” he thought her industrious and more musically gifted “than her performance shows.” That said, he described Ruth as “a hard but undisciplined worker” who “practices a great deal but [is] blind to her defects.”7

In November 1921, fifty-year-old Julius Krauss died of leukemia. Ruth had been very close to her father, and after he died, she gave up the violin. The following year, she left the Peabody Conservatory for good. Having dropped out of high school, abandoned art school, and failed at the conservatory, Ruth was adrift. She shared an apartment with her mother and wondered what to do with herself. She went to work as a cashier in 1923, becoming a clerk in 1926 and a manager the following year. At some point during these years—possibly during 1924 and 1925—they lived with Blanche’s sister, Edna Hahn; her husband, Charles; and their son, Richard. Though Dick was twelve years Ruth’s junior, he became like a younger brother to her, and their close friendship endured throughout their lives.8

In 1927, Blanche’s mother, Carrie Rosenfeld, died, prompting Ruth to make a decision about her future and giving her the money she needed to act. She would leave home and become an “artiste”: As she later wrote, “Naturally one cannot become an artiste if one remains at home.” Fur designer John Gray recommended that she apply to New York’s School of Fine and Applied Art, popularly known as the Parsons School. For the first time, she would move away from Baltimore, where she had lived in for twenty-six years. She would be going not to a small, supervised camp in Maine but to the largest city in North America. In the late summer of 1927, with renewed determination and sense of purpose, Ruth packed her bags and boarded the train for New York.9

She enrolled full time, paying a hefty tuition of $250 for her first year and living in one of New York City’s many “girls’ clubs”—likely either the Three Arts Club or the Parnassus Club, which were recommended in the school’s 1927–28 Prospectus. Receiving credit for her costume design coursework at the Maryland Institute of Art, Ruth enrolled as an “honor student” in costume design and illustration, a popular new major introduced the previous decade by school president Frank Parsons. According to Ruth, being an “honor student” meant “that I skipped the part where you had to work in materials themselves, and stuck only to the drawing and painting part, the part I was interested in.”10

Though Ruth preferred the aesthetic pleasures of drawing and painting, she could not avoid the Parsons School’s emphasis on the practical. Frank Parsons wanted students to become good artists, but he also wanted them to be able to get a job. Influenced by Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius’s belief in “the basic unity of all design in its relation to life,” Parsons taught its pupils to extend aesthetic judgment into the everyday, an idea that resonated with Ruth’s interest in colloquial language. Parsons students learned to see beauty in ordinary things. Designing a chair should be as important as designing a building; an advertisement should be designed with as much care as a mural. Frank Parsons believed that teaching students to develop good taste would democratize art. Furthermore, as he told students in 1927, “If you can produce taste in advertising, costumes, interiors, you can get the job.”11

In her first term at Parsons, Ruth faced one required class that nearly made her quit: dynamic symmetry. Based on his study of Greek art and design, Jay Hambidge concluded that beauty was based on symmetry. Naming the Greeks’ lost principle “dynamic symmetry,” he devised a mathematical formula—known as the Golden Ratio, 1.6180 (also rendered as 1:√5)—to express the relationship between elements of a particular object. That object could be anything: a drinking cup, a chair, a building, a book layout, or architectural decoration. Putting Hambidge’s principle into practice, Parsons instructors had students use geometry to map the symmetry of an object before sketching it. The idea was that the mathematical calculations would gradually become second nature to students who practiced dynamic symmetry, thereby bringing the “craft inheritance” of the Greeks to modern design.12

Ruth began her battle with the subject in July 1927, when she took life drawing. Determined to follow her instructor’s guidance to the letter, Ruth so obsessed over each detail that she lost sight of her larger aims. As she recalled with more than a little irony many years later, “Since my meticulousness and literal following of teaching was, to put it politely, naïve, my first year’s output—giving say Life drawings as an example—resembled architectural floor plans for labyrinths. The human figure was found to have more variety by me than by all the other artists of the ages thrown together. I did finally ‘master’ the art of ‘seeing’ and I became very adept at drawing by discernment of rhythms alone—a sort of transmission of ‘tactile perceptions,’ a form of abstracting essentials to represent the whole, the abstraction itself on a ruggedly individual level of feeling. Is level the right word? Oh well.” Her tenacity helped her master the subject, even if she never fully understood the theory.13

Parsons required Ruth to work hard, and she rose to the challenge, pursuing her homework with single-minded intensity: If confining herself to her room for a few days might yield results, Ruth was willing to try.14

They were fiends at Parson’s [sic] for exact matching of color and many other details. On one painting I remember spending days mixing tones of “rose.” I mixed in actual fact three hundred different tones of rose trying to get a background color combining “a sense of brightness and doom.” I was living at a girls’ Club at the time and locked myself in my room for several days, having my meals sent up (for a quarter extra) trying to get the “rose.” Finally I was set. I put it on. It turned out entirely different-looking over the large background area than in my sample, of course—but anyway they were pretty exacting in certain ways at Parson’s. What I am driving at is that I spent an awful lot of time, thought and feeling, on “Art.”

Ruth Krauss, n.d. Image courtesy of Betty Hahn.

To prepare for the working world, Parsons required costume design students to draw up and create various types of costumes, including personal clothes. In 1928–29, she received critiques from art deco illustrator Georges Lepape, whose fashion designs pioneered greater physical freedom in women’s clothes. Ruth was very much in favor of that idea, as was fellow costume design major Claire McCardell, who was a year ahead of Ruth at Parsons and who would revolutionize American women’s fashion by making clothes that were stylish, comfortable, and affordable—putting the school’s principles into practice.15

After two years of study and a bout with the measles, Ruth graduated from Parsons in June 1929. While seeking work, she moved in with an Italian man she later identified only as Guido, with whom she had her “first physical ‘affair.’” Fifty years later, Ruth recalled her younger self as always having been “boy-crazy” and described sex as “a paramount feature in my feeling & thinking.” Also in the late 1920s, she had a brief affair with sculptor Isamu Noguchi, who had just returned to New York from Paris.16

With her Parsons education, Ruth Krauss felt poised for success: “I left Parsons able to work in all mediums, from pencil and charcoal through water color, ‘gouache,’ and oils, to finger-paint.” Her confidence soon crashed, along with the stock market: As an art school graduate during the Great Depression, Ruth “found a few jobs, but I had to walk my feet off and sit humiliated for hours in offices waiting and hang around three months between jobs for which I was then paid thirty to fifty dollars—or on one big haul, not at all. Because the magazine itself folded up. Among other things I did the first picture-jacket ever used by the Modern Library. It was for Alice in Wonderland” (1932). She also did the book jacket for the Modern Library’s edition of Gulliver’s Travels (1932).17

With jobs few and far between, Ruth survived the depression in part thanks to the financial support of her mother, who continued to run the Krauss family’s furrier business until March 1930, when she married Albert A. Brager, a wealthy widower and founder of the Brager-Eisenberg department store.18

In the early 1930s, Ruth met Lionel White, a journalist and writer of detective stories, who was working on an edition of Lewis Carroll’s Logical Nonsense: Works, Now, for the First Time, Complete. According to Ruth, she and Lionel met at an “Arts Ball,” where they danced and laughed together. Both were in costume: “I think I was dressed like a boy—Lionel was dressed I can’t remember how but not like a girl.” After the party, the two walked hand in hand through Greenwich Village. Ruth was in love.19