The ramifications of a financial panic are—SAY! … That never occurred to me! … Your dad fired! Denied access to means of producing the necessities of life! You and your mother in rags! The icebox bare— Cushlamochree! The icebox bare!

—MR. O’MALLEY, in Crockett Johnson, Barnaby, 5 April 1945

In 1926, unable to afford their home of a dozen years, the Leisks moved about two miles west into a house at 53 North Prince Street (now 33-43 Prince Street) in Flushing, Queens. The new house was only ten feet wide, especially cramped for a family that included Dave’s cousin, Bert Leisk, and his friend, Jim McKinney, who had fled Britain’s postwar economic slump in 1923. Glad for a temporary escape from these close quarters, Dave sought work.1

Department stores were thriving in the 1910s and 1920s—Marshall Fields in Chicago, Filene’s in Boston, and Macy’s in New York. In the winter of 1926, on the strength of his Cooper Union art courses, Dave became the assistant art director in Macy’s advertising department, a position he described as “a glorified office boy.” Macy’s had strict rules for its more than five thousand workers: As at Newtown High School, those who arrived at work after 8:45 needed to obtain a special pass, without which they could neither enter the locker rooms nor go to their jobs. Working in the advertising department gave Dave a chance to develop skills in typesetting and illustration but few opportunities to express his creative side. Department managers requested ads, staff members drew items to be advertised, and other staff created advertisements that conformed to Macy’s style, using the company’s distinctive typefaces and trademark red star. Artists had no control over the final layout.2

If these rigid conditions clashed with Dave’s creativity, the culture of advertising could not have increased his job satisfaction. As copywriter Helen Woodward wrote in 1926, “To be a really good copywriter requires a passion for converting the other fellow, even if it is to something you don’t believe in yourself.” Naturally skeptical, Dave did not stay at Macy’s for very long, quitting just before he was fired for wearing a soft collar instead of a regulation stiff one.3

Dave next found employment hefting ice in an icehouse. He may also have played semi-professional football for the Flushing Packers. He enjoyed the game because it wasn’t much of a “passing game. It was mostly just a bumping-down-on-the-ground game.” All Dave, a big offensive lineman, had to do was lean. Dave and the other linemen would mock the alleged arrogance of the quarterback. “The slick quarterback thinks he’s the team,” Dave would say. After a pause, he would add, “We are.”4

Just two weeks after his twenty-first birthday, Dave returned to publishing, becoming the first art editor of Aviation, which eventually evolved into Aviation Week. The cover of the 7 November 1927 Aviation, the first issue on which Johnson worked, displays a photo of Charles Lindbergh’s Spirit of St. Louis flying back to New York. Just a few months after his historic solo flight from New York to Paris, Lindbergh had undertaken an aerial tour of all forty-eight states to promote aviation, appearing before huge crowds and receiving accolades. Moreover, the latter half of 1927 saw four other successful transatlantic flights as well as the first flight from the continental United States to Hawaii, events that Aviation covered with enthusiasm.5 On the strength of his new income, Dave and his mother and sister moved to more comfortable quarters at Hyacinth Court, a new four-story apartment building in Flushing.

During his years at Aviation, Dave began taking typography and graphic design classes at New York University’s School of Fine Arts, where one of his teachers was Frederic Goudy, a master of print design who invented more than a hundred typefaces. Goudy described his work as “simple[;] that is, it presents the simplicity that takes account of the essentials, that eliminates unnecessary lines and parts,” articulating an aesthetic that finds echoes in Johnson’s later view of his illustrations as “simplified, almost diagrammatic, for clear storytelling, avoiding all arbitrary decoration.”6

Dave was also receiving an on-the-job education in layout and design. In early 1929, publisher James McGraw added Aviation to his portfolio of business periodicals. During the corporate reshuffling that followed, Dave became art editor of a half dozen McGraw-Hill trade publications, apparently including American Machinist and Bus Transportation. However, the stock market crashed less than eight months after Dave joined the McGraw-Hill payroll. The company’s fortunes declined along with the economy as circulations dropped and some magazines disappeared entirely. McGraw-Hill laid off large numbers of editorial and business personnel, and Dave and the others who remained received significantly reduced salaries.7

David Johnson Leisk, ca. 1930s. Photograph by Eliot Elisofon. Image courtesy of Smithsonian Institution. Used by permission of the Harry Ransom Research Center, University of Texas at Austin.

Like many members of his generation, Dave turned left. He joined the Book and Magazine Writers Union. He read Communist publications such as the Daily Worker and New Masses and befriended others in the movement, including Charlotte Rosswaag. He also fell in love with her.

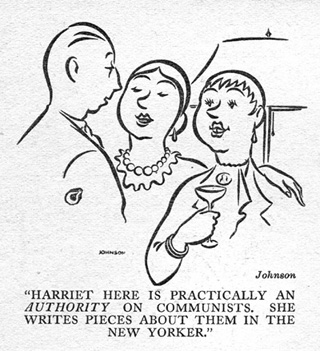

Crockett Johnson, “Harriet Here Is Practically an Authority on Communists. She Writes Pieces about Them in the New Yorker,” New Masses, 17 April 1934. Image courtesy of Tamiment Library, New York University. Used by permission of International Publishers, New York.

Like Dave’s mother, Charlotte was a strong-willed German. Born in 1908, Charlotte emigrated to the United States with her family in 1915. Her father, Adolph, worked as a diamond cutter for a jewelry factory, while her Polish-born mother, Veronica, both kept house and cleaned others’ houses. According to Mary Elting Folsom, who knew Dave and Charlotte during the 1930s, Charlotte had a “rather plain, very lively face” and “was always laughing.” She was free-thinking and plain-spoken and shared Dave’s progressive politics. Charlotte could be blunt, but her sense of humor softened the edges of her frankness. All in all, Charlotte was “a very pleasant, laughing person, but a tough lady.” By the mid-1930s, Dave and Charlotte were married and living with their two dogs in a garden apartment on or near Bank Street in Greenwich Village. She was a city social worker, and Dave continued to do magazine layout for McGraw-Hill.8

Dave met Mary Elting; her future husband, Franklin “Dank” Folsom; and other radicals through the Book and Magazine Writers Union. Elting, a magazine editor and later prolific a children’s author, cofounded the union with Viking editor David Zablodowsky, McBride editor Elizabeth Morrow “Betty” Bacon, editor Alex Taylor, and others. Through the union, Dave also befriended Daily Worker journalist Sender Garlin and TASS editor Joe Freeman.9

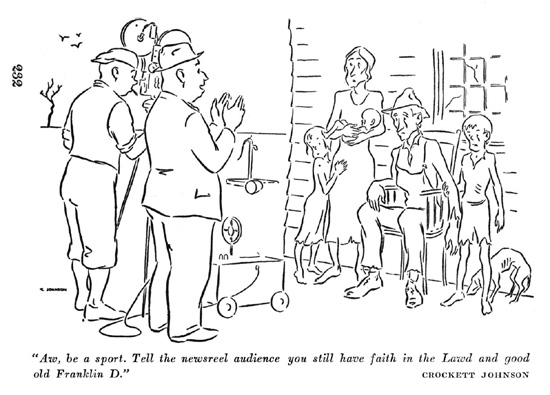

“Aw, be a sport. Tell the Newsreel Audience You Still Have Faith in the Lawd and Good Old Franklin D.,” New Masses, 28 August 1934; reprinted in Robert Forsythe, Redder Than the Rose (New York: Covici, Friede, 1935). Used by permission of International Publishers, New York.

Freeman also served on the editorial board for New Masses, and Crockett Johnson began to contribute to the Communist publication, which had just begun appearing weekly. His first cartoon appeared in the magazine on 17 April 1934 and mocks self-professed experts on communists. Three months later, New Masses printed another cartoon in which Johnson skewers President Franklin D. Roosevelt for his concern with the well-being of the rich. Billionaire industrialist J. P. Morgan reclines on a deck chair on a luxury liner, the Corsair, a name that connects Morgan to piracy. A young man delivers a message: “Radiogram, Mr. Morgan. The White House wants to know are you better off than you were last year?”

In 1932 and 1933, 24 percent of Americans were unemployed, up from 3.2 percent in 1929. Though the unemployment rate would drop to 21 percent in 1934, the nascent New Deal had yet to produce major results. It was a time when people went on hunger marches, when police shot strikers, and when general work stoppages shut down major U.S. cities. As Michael Denning writes, “The year of the general strikes—1934—was also the year young poets and writers proclaimed themselves ‘proletarians’ and ‘revolutionaries.’”10 Johnson announced his sympathy with the proletarians and revolutionaries. In another cartoon commenting on the wave of strikes that swept the United States during 1934, a young lady at a cocktail party asks a young man, “Was it Marx, Lenin, or Gen. [Hugh] Johnson [a supposedly neutral mediator in a walkout by San Francisco longshoremen] who said: ‘The general strike is quite another matter’?” Johnson mocks a bourgeoisie that in its ignorance confuses revolutionary thinkers with the general whose comments aided the suppression of the strikers. Taking on the Hearst press, a May 1935 cartoon has a secretary from Hearst’s International News Service hand an article back to its author, saying, “Mr. Hearst says he’ll buy your farm articles if you’ll just change ‘Arkansas,’ ‘Louisiana,’ and ‘California’ and so on, to Soviet Russia.”

He signed his first cartoons simply “Johnson.” By August 1934, he began signing them “C. Johnson,” sometimes reverting to “Johnson” and once to “C. J. Johnson.” Whatever name appeared on the image itself, New Masses nearly always printed his byline as “Crockett Johnson,” the public debut of his pseudonym. The first cartoon to bear that name was published on 7 August 1934 and showed a wealthy capitalist wife complaining, “Just because your greedy workmen decide to go on strike I can’t have a new Mercedes. Somehow it doesn’t seem fair.” Thoughtful, soft-spoken art editor Dave Leisk had become radical cartoonist Crockett Johnson.