Cushlamochree! Broke my magic wand! You wished for a Godparent who could grant wishes? Lucky boy! Your wish is granted! I’m your Fairy Godfather.

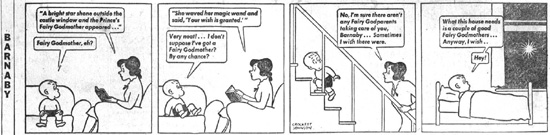

—MR. O’MALLEY, Barnaby, 21 april 1942

Crockett Johnson tried for more than two years to find a home for Barnaby. In addition to the abortive effort at self-syndication, Johnson’s idea was rejected by Collier’s. But shortly after the move to Darien, Charles Martin, Johnson’s friend and the art editor of the new PM, came to visit and saw a half-page color Sunday Barnaby strip. He offered the strip to King Features, which rejected it. But PM’s comics editor, Hannah Baker, loved it.1

Founded in 1940 by former Time editor Ralph Ingersoll, PM was a Popular Front newspaper. Original plans for the publication did not include comics, but Dante Quinterno’s Patoruzu began running in August 1941, followed in December by the antifascist adventure strip Vic Jordan by Paine (the pseudonym of Kermit Jaediker and Charles Zerner). The progressive paper’s readers included Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Eleanor Roosevelt, Vice President Henry Wallace, bandleader Duke Ellington, and writer Dorothy Parker. It printed writings by future Speaker of the House Thomas P. “Tip” O’Neill, Ernest Hemingway, and Erskine Caldwell; photographs by Margaret Bourke-White and Weegee (Arthur Fellig); maps by George Annand; and cartoons by Carl Rose, Don Freeman, and Theodor Geisel (Dr. Seuss).2

PM was pro–New Deal, anti–poll tax, and antifascist. When the newspaper received criticism for its leftist politics or its failure to gain a wider circulation, Geisel rose to its defense, praising it as a courageous voice amid an otherwise docile domestic news media. In March 1942, he wrote, “Give this paper a break—remember that for almost a year it was a lone voice in American journalism sounding the alarm that America would be attacked.” To avoid compromising its editorial judgment, the paper refused to run ads, relying instead on subscriptions and on department store heir Marshall Field III and other progressive investors to pay the bills.3

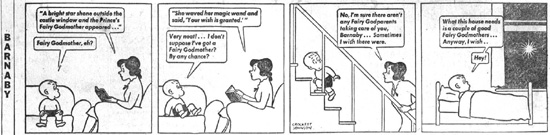

Crockett Johnson, Barnaby, 20 April 1942. Image courtesy of Rosebud Archives. Reprinted with the permission of the Estate of Ruth Krauss, Stewart I. Edelstein, Executor. All Rights Reserved.

Crockett Johnson, Barnaby, 21 April 1942. Image courtesy of Rosebud Archives. Reprinted with the permission of the Estate of Ruth Krauss, Stewart I. Edelstein, Executor. All Rights Reserved.

PM’s readers met Barnaby Baxter on 14 April 1942 in an advertisement that shows him walking, looking up, and calling “Mr. O’Malley!” Several more ads followed before the strip made its debut on 20 April.

Johnson always claimed that O’Malley was not based on any particular person. Eight months after the strip’s debut, Johnson said, “None of my friends, in spite of what their friends have been saying, is Mr. O’Malley.” He continued, “O’Malley is at least a hundred different people. A lot of people think he’s W. C. Fields, but he isn’t. Still you couldn’t live in America and not put some of Fields into O’Malley. O’Malley is partly [New York] Mayor [Fiorello] La Guardia and his cigar and eyes are occasionally borrowed from Jimmy Savo,” a vaudeville comic and singer.4

For all the attention that Mr. O’Malley would ultimately receive, Johnson always considered Barnaby the star: “Even if Mr. O’Malley gets all the notice, it’s still Barnaby who is the hero. We’re all looking at Mr. O’Malley through Barnaby. He couldn’t exist without The Kid.” In late 1943, he answered the question of who had inspired Barnaby: “I don’t get anything much from kids. How can you? They are all different. And I don’t draw or write Barnaby for children. People who write for children usually write down to them. I don’t believe in that…. [W]hen it comes to knowing about children, it’s a terribly old thing to say, but everyone was once a child himself.”5

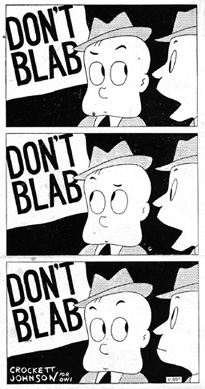

Crockett Johnson, “Don’t Blab,” cartoon for the Office of War Information, ca. 1942. Image courtesy of the National Archives II, College Park, Maryland. Reprinted with the permission of the Estate of Ruth Krauss, Stewart I. Edelstein, Executor. All Rights Reserved.

In the earliest strips, Johnson was still working out his style, the characters, and the boundaries between O’Malley’s world and the world of the grownups. In addition to Barnaby, Dave continued to write the Little Man with the Eyes for Collier’s and served as liaison between the U.S. Treasury Department and American Society of Magazine Cartoonists, helping to promote the War Bond campaign. He wrote the script for a War Bond strip drawn by Ellison Hoover that ran “in house organs of big companies.”6

Ruth Krauss continued to commute into New York to take anthropology courses at Columbia. Her instructors included Gene Weltfish, whom she considered “a friend,” and Ruth Benedict, whom Krauss “used to go and hear … lecture the way some people go to plays.” She also sought to contribute to the war effort by “fighting ‘Fascism,’ on the home front as well as abroad. Also seeing the disappearance of all attitudes involving cruelty to others or denial of the rights of others; and having these attitudes supplanted by those based on scientific research and a sense of fairness,” as she wrote in March 1944. When the idea of distributing an antiracist pamphlet among the members of the U.S. armed forces came up, Krauss and about a dozen others connected to Columbia’s anthropology program drafted ideas that would inspire Benedict and Weltfish’s best-selling The Races of Mankind (1943).7

A thirty-two-page booklet illustrated by Ad Reinhardt, The Races of Mankind used science to show that we are all “one human race” and that culture, not nature, explains differences between peoples. In the 1940s, this idea was controversial. Among those who objected, Kentucky congressman Andrew May was upset by Benedict and Weltfish’s use of data from World War I army intelligence tests in which southern whites scored lower than northern blacks and by the authors’ contention that “the differences did not arise because people were from the North or the South, or because they were white or black, but because of differences in income, education, cultural advantages, and other opportunities.” May persuaded the army not to distribute The Races of Mankind, thereby inspiring public protests, garnering media coverage, and boosting sales. The pamphlet sold nearly a million copies in its first ten years and was translated into French, German, and Japanese.8

Barnaby rapidly built a devoted following among culturally influential people, including Dorothy Parker, W. C. Fields, Terry and the Pirates creator Milt Caniff, and Duke Ellington. When O’Malley and Barnaby visited a radio station in a November 1942 strip, O’Malley said, “Give ear to the strains of this Duke Ellington opus, m’boy … Sizzling but solid—as we cognizant felidae say.” Ellington subsequently wrote in to PM, “Please tell Crockett Johnson to thank Mr. O’Malley on my behalf for coming out as an Ellington fan. That makes the admiration mutual.” He concluded, “Tell Barnaby that I believe in Mr. O’Malley—solidly.” When the first Barnaby collection was published in September of the following year, Parker wrote, “I think, and I am trying to talk calmly, that Barnaby and his friends and oppressors are the most important additions to American arts and letters in Lord knows how many years. I know that they are the most important additions to my heart.”9

Despite its prominent fans, the comic’s circulation grew slowly. In late 1943, Barnaby was in 16 American newspapers, and by the following October, that number had grown to 33. At its height, Barnaby was syndicated in only 52 papers. (By contrast, Chic Young’s Blondie, the strip with perhaps the largest circulation, was appearing in as many as 850 papers at that time.) As Johnson observed in late 1942, “If Dick Tracy were dropped from the News, 300,000 readers would say, ‘Oh dear!’ But if Barnaby went from PM, his 300 readers would write indignant letters.” Though it never had a mass following, Barnaby was by 1943 already earning Johnson five thousand dollars per year.10

Crockett Johnson, illustration from Constance Foster, This Rich World: The Story of Money (New York: McBride, 1943). Reprinted with the permission of the Estate of Ruth Krauss, Stewart I. Edelstein, Executor. All Rights Reserved.

In the spring of 1943, Johnson’s career branched in another direction when he illustrated his first children’s book, Constance J. Foster’s This Rich World: The Story of Money. Along with Ruth Brindze’s Johnny Get Your Money’s Worth (1938), This Rich World is one of the first wave of children’s books inspired by the consumer movement, designed to educate children about money and the marketplace. Expressing Foster’s understanding that “many of our problems are economic at root,” This Rich World is also the sole children’s book to display any hint that Johnson was once a New Masses editor. One illustration notes that “Millionaire Cadwalader and thirty-dollar-a-week Tom Kent pay the same indirect taxes,” a not-so-subtle criticism of the flat nature of the sales tax. Another suggests the precariousness of an economic system built on borrowing. One man in a suit gives a thousand-dollar deposit to another man in a suit, identified as banker. The banker then gives a thousand-dollar loan to another man in a suit, who gives a thousand-dollar check to the first man.11

For her part, Krauss soon became annoyed that when a student did research, the professor’s name went on the publication. Moreover, her anthropological work made her acutely aware that children quickly absorb the values of their culture; effecting change would require reaching children early in life. When she discussed this idea with one of her friends, the friend responded, “You should be writing for children and not doing this.” Inspired, Krauss started writing a book that she hoped would give children progressive ideas. She undertook an anthropological examination of prejudice that would teach children about the dangers of fascism and anti-Semitism.12

She took her manuscript to Harper and Brothers, riding the elevator up to the office of Ursula Nordstrom. Nearly a decade younger than Krauss, Nordstrom had joined Harper in 1931 and had become director of the Department of Books for Boys and Girls in 1940. When Krauss stepped off the elevator, she met Nordstrom’s assistant, Charlotte Zolotow, who was supposed to screen visitors. Zolotow remembered a young woman with “disheveled hair,” an “off-beat” sense of humor and “perspective about life,” and obviously strong “feelings for children.” After a few minutes, Zolotow went into Nordstrom’s office and said, “You’ve got to see her, you’ve got to see her!” Nordstrom and Krauss then talked for a long while. After Krauss left, Nordstrom told Zolotow, “She’s wonderful, and she’s going to write a book for us.” But it would not be the manuscript Krauss had brought with her: “That was a life of Hitler, and I didn’t think that would do for the children’s book world.”13

Before the end of World War II, children’s books that tackle prejudice are rare. In the wake of the war, Ernest Crichlow’s illustrations for Jerrold and Lorraine Beim’s Two Is a Team (1945) show black and white children who are best friends. H. A. and Margret Rey, the creators of Curious George and acquaintances of Krauss and Johnson, created Spotty (1945), in which spotted bunnies and white bunnies learn to get along. Ruth’s manuscript was still a couple years ahead of the curve.14

Johnson, too, was working on what would become his first published book, revising and redrawing the best episodes of Barnaby’s first ten months for publication in a single volume in the fall of 1943. He also continued to work on new daily Barnaby strips, usually at night. Sitting at his desk and smoking a cigarette, Johnson would write and draw from 11:00 at night until 5:00 the next morning. He usually spent two nights writing the week’s script, followed by two nights drawing the strips. Sometimes he was running so late that at 6:00 in the morning, he would bring his strips, ink still wet, to his neighbor Bob McNell, who would drop them off at the PM Syndicate on the way to his job in New York City. Like his character, Harold, Johnson relied on his ability to improvise under pressure. Just as, when falling off a cliff, Harold keeps “his wits and his purple crayon” and draws himself a balloon, so the approaching deadline focused Johnson’s wit, igniting his imagination at night.15