Then, the man and the girl get married.

They hold hands

and they ride home

—galoop galoop galoop galoop

galoop galoop galoop galoop—

together.

—RUTH KRAUSS, Somebody Else’s Nut Tree and Other Tales from Children (1958)

Dave’s working methods meant that he and Ruth kept very different hours. Ruth rose at seven in the morning, after which she would take their two dogs for a walk along the Five Mile River. While he slept, Ruth began working on story ideas in her upstairs studio. Dave rose at noon, and Ruth fixed his breakfast and her lunch shortly thereafter. Then he would read for about two hours before working in their Victory Garden or going sailing while she swam. At 5:30, they had dinner, prepared by Ruth. Dave would start work on Barnaby at 8:00 but found that he only really got under way after the 11:00 news. Despite living in different personal time zones, they were a very close couple—so close that, on 25 June 1943, they got married in New London, Connecticut.1

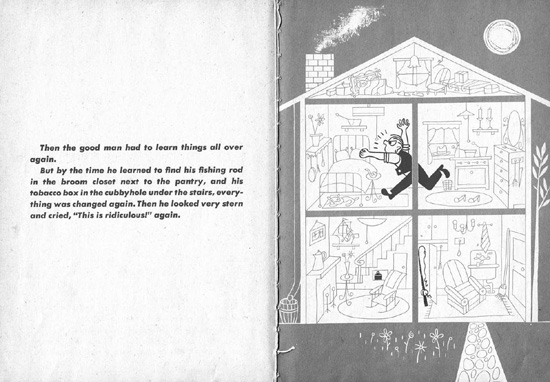

Harper gave Krauss a three-hundred-dollar advance and a contract for her first children’s book in October 1943. Influenced by her work on Ruth Benedict’s anthropological project on south Italian farming families, A Good Man and His Good Wife offers a novel twist on folktales that mock a husband’s failed attempts to copy his wife. In contrast, Krauss has mimicry supporting the husband’s efforts to teach a lesson to the wife. Nonetheless, as Krauss admitted four years later, A Good Man and His Good Wife “made some mistakes” because “the characters are cast in the conventional roles.” The “good man” can never find anything because his good wife keeps moving things around, explaining, “My dear, I get so tired of the same things in the same place.” Frustrated, he puts his shoe on his head, his garters around his neck, his tie around his knee, his pants on his arms, his coat on his legs, his spectacles on his elbow, and his socks on his ears. He then sits on the breakfast table, eating his napkin and wiping his face with a biscuit. When his wife exclaims, “My dear, this is ridiculous!,” he replies, “My dear, I get so tired of the same things in the same place.” The tactic cures “his good woman of a bad habit”: she stops moving things around.2

Ad Reinhardt, two-page spread from Ruth Krauss, A Good Man and His Good Wife (New York: Harper, 1944). Reproduced courtesy of Anna Reinhardt. Copyright © Anna Reinhardt.

Ad Reinhardt received the same advance and worked up a rough dummy of the book while Krauss pondered her next project, an anti-ageist children’s book, I’m Tired of Being a Grandma. Ursula Nordstrom found parts of the beginning amusing but considered the manuscript “forced” and “not a really good follow-up to A Good Man and His Good Wife.” Krauss persisted, sending Nordstrom two new versions of the story because “our concepts of how people think, feel, and behave at certain ages, are socially conditioned,” and these concepts were “practically as bad as race-prejudice, prejudice against women, immigrants, etc.” Krauss pointed to “the Northwest Coast Indians of the United States and Canada” as holding “entirely different concepts about old people”: “Among these Indians, the high point of romantic sex is old-age, about seventy to ninety. You’re supposed to be romantic then; so, consequently, you are romantic then.” Though sympathetic, Nordstrom did not think the idea worked as a story.3

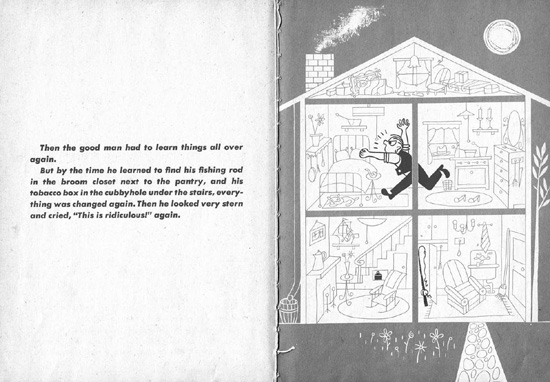

Crockett Johnson with the cover drawing for Barnaby (New York: Holt, 1943). Image courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution. Reprinted with the permission of the Estate of Ruth Krauss, Stewart I. Edelstein, Executor. All Rights Reserved.

Also in October 1943, Henry Holt published Barnaby, bringing the darling of the smart set to a wider audience. Rockwell Kent praised “Crockett Johnson’s profound understanding of the psychology of the child, of grownups and of fairy godfathers.” William Rose Benét, who won the 1942 Pulitzer Prize for poetry, called Barnaby “a classic of humor” and declared Mr. O’Malley “a character to live with the Mad Hatter, the White Rabbit, Ferdinand, and all great creatures of fantasy.” Ruth McKenney, whose My Sister Eileen had been nominated for an Oscar earlier that year, took delight in “that evil intentioned, vain, pompous, wonderful little man with the wings.” She “suppose[d] Mr. O’Malley has fewer morals than any other character in literature which is, of course, what makes him so fascinating.” Dorothy Parker began her “Mash Note to Crockett Johnson” by confessing that she had tried and failed to write a review of his work: “It never comes out a book review. It is always a valentine for Mr. Johnson.”4

The first printing of ten thousand copies sold out in just a week, and sales reached forty thousand copies by the end of the year. The 4 October issues of both Life and Newsweek ran features on Barnaby. Reprinting the ten-strip sequence in which Gorgon, the dog, begins to talk, Life described Barnaby “as a breath of sweet cool air” and thought the comic “written and drawn with the intelligent innocence of a Lewis Carroll classic.” Newsweek’s profile reprinted some of the positive press, noting that, although “only seven papers” run Barnaby, “the intense enthusiasm of their small audience more than offsets the lack of numbers.” Indeed, if PM were “to cease publication tomorrow, the first question asked by a large bloc of its 140,000-odd readers would be: ‘Where is Barnaby going?’” On 9 November, New York’s Norlyst Gallery began a four-week exhibition of original Barnaby strips. For two hours on opening night, Crockett Johnson sat at a table between two mounted displays of his Barnaby comics. With cigarette in his left hand and pen in his right, he signed copies of Barnaby for fans, including Broadway actress Paula Laurence and painter Jimmy Ernst.5

Of all the Barnaby characters, only O’Malley truly captured the public’s imagination. When Barnaby fan clubs began to form, they inevitably named themselves after the club to which O’Malley belongs, the Elves, Leprechauns, Gnomes, and Little Men’s Chowder and Marching Society. Such societies formed not only in New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut but also in Colorado and in Italy (founded by a serviceman). One fan urged the postmaster general to issue an O’Malley stamp, and another nominated him as Time’s Man of the Year. In 1944, O’Malley inspired both a song (“Mr. O’Malley’s March”) and an ad campaign for Crown Zippers. To capitalize further on the strip’s success, PM’s Hannah Baker licensed the manufacture of dolls based on the Barnaby characters, although war shortages delayed production and Baker eventually abandoned the project.6

Krauss continued to envision other ideas for books, none of them successful. In January 1944, she sent Nordstrom Elizabeth Hears the Story of Our Flood, based on her experience of the 1936 Bucks County flood. In February, Krauss sent Nordstrom a rough dummy for what she called “a ‘culture’ book for older children: i.e. putting across the idea that behavior taken by us for granted as natural is actually conditioned.” Nordstrom was not interested in either book but encouraged Krauss to keep trying.7

Krauss’s next idea came after she found herself imagining a conversation with the five-year-old boy who lived next door. The result was a one-hundred-word story, The Carrot Seed, about a little boy who believes his carrot will come up even though everyone tells him that it won’t. Johnson created an illustrated dummy for the book, and Nordstrom loved it. In late May 1944, Johnson and Krauss received book contracts and advances of three hundred dollars each. Krauss joked that on a per-word basis, she had become “the highest paid author of the printed word.” Ruth was proud of herself. For the first time, she seemed to be succeeding in her chosen occupation.8

Because Barnaby had given Crockett Johnson name recognition and Ruth Krauss lacked it, Harper’s marketing department initially promoted The Carrot Seed to bookstores as illustrated by Crockett Johnson and “written by his wife.” Angry, Krauss wrote to her publisher that the phrase was “embarrassing because I’m made to trade on another person’s reputation.” The wording implied that the “artist with reputation illustrates this book, not because it is a good book and one that he’s interested in illustrating, by a writer named Ruth Krauss, but because he’s being nice to his wife, Ruth Krauss, who’s [sic] book probably stinks except that he’s probably touched it up here and there.” Nordstrom found Krauss’s attitude “incredible” but nevertheless told her, “OK—we’ll never mention your marital connections again.”9

With two-color cartoon illustrations by Reinhardt, A Good Man and His Good Wife was published in the fall of 1944. Although it now seems somewhat sexist, reviewers at the time found it funny and offered praise. The Magazine of Art named it one of the year’s best children’s books, “infused … with real wit” that would be “enjoyed by people of all ages.” Three decades later, critic Barbara Bader wrote that “nonsense” is key to the tale’s appeal. The man’s tactic of taking his wife’s words at face value is “not unlike the way kids confound their elders, sometimes innocently, sometimes not, by taking their words literally too.”10

Once Barnaby became moderately successful, Johnson found that creating a finely tuned daily strip required a lot of work: “There’s nothing worse than the obligation to be funny.” He realized that he needed help. Fresh out of the army, Howard Sparber got a job at PM, thinking that he would be a staff artist. When he reported for work, however, he learned that Johnson had seen Sparber’s portfolio and wanted to hire him as an assistant to do inking on Barnaby.11

Meeting Johnson’s exacting standards was a challenge. According to Sparber, “I could never quite grasp the tightness of his line. I learned a great deal from him, but I didn’t draw that way.” Sparber saw Johnson as more than a perfectionist: “Perfectionist is sort of ordinary. He was way beyond that.” Johnson’s background in layout and in typography inspired him to set his dialogue in type. Barnaby was the first strip to always use typeset dialogue, with Johnson using italicized Futura medium. Designed by German typographer Paul Renner in the 1920s, Futura embodies the Crockett Johnson aesthetic: it excises needless detail, rendering its simple geometric forms in precise lines of uniform width. This devotion to precision informs Johnson’s diction, too. As Sparber explained, the type “wasn’t just sort of dashed in. Dave would be writing the text as if he was counting characters in his head, because he knew he had to do five lines to fit into a balloon that would be over Mr. O’Malley’s head.”12

Once a week, Sparber went to the type shop at PM and picked up the type to be pasted into the Barnaby speech balloons, along with galleys of completed but wordless strips, and brought the materials to Darien. Sparber would stay with Krauss and Johnson for two or three days while Johnson wrote a week’s worth of new Barnaby dailies and pasted the words into the galleys of the earlier strips. Because Johnson worked at night, Sparber saw little of him, although “once in a great while, he’d come down and we’d have breakfast together. Then he’d get back upstairs because he was tired—he had to get to sleep in the day.”13

Johnson was also working on a new Barnaby book. As with the first collection, he selected only the best strips, revising and redrawing seven months’ worth of work for inclusion in Barnaby and Mr. O’Malley. Probably aided by his friend Joseph Skelly, a Du Pont Chemical engineer who may have been a model for Atlas, the strip’s slide-rule-carrying “mental giant,” Johnson revised the math formulae in the 26 May 1943 strip, when Atlas meets Barnaby’s fairy godfather but forgets his name. In the original strip, Atlas speaks a mathematically meaningless formula that serves as a mnemonic for O’Malley; in the revised version, however, the formula has meaning:

As J. B. Stroud shows, Euler’s equation demonstrates “that eΠi+1=0.” Simplifying the next component,  . Thus far, Atlas’s formula spells out “0 + MA.” Unscrambling the rest of the equation, Stroud proves that The equation thus spells O’Malley, a complex joke comprehensible only to mathematicians. The math professors not only got the joke but used Barnaby strips in their lectures. In late 1948, when Engineering Research Associates got the go-ahead to build a code-breaking computer for the U.S. government, the engineers named the machine Atlas.14

. Thus far, Atlas’s formula spells out “0 + MA.” Unscrambling the rest of the equation, Stroud proves that The equation thus spells O’Malley, a complex joke comprehensible only to mathematicians. The math professors not only got the joke but used Barnaby strips in their lectures. In late 1948, when Engineering Research Associates got the go-ahead to build a code-breaking computer for the U.S. government, the engineers named the machine Atlas.14

The sophistication was too much for some. In late June 1944, the Baltimore Evening Sun dropped Barnaby because managing editor Miles H. Wolff thought it “had not held up and was getting rather boresome.” The Sun soon found itself flooded by letters demanding the return of Barnaby and his fairy godfather: “A dastardly attack has been made upon the most subtly sophisticated character of our time,” wrote Mary E. O’Malley (who described herself as “no relation!”). “Here at last we have a comic that captures completely the magical world of childhood,” she continued, “where … the adult world is revealed in all its cynical dullness.” Fans signed a petition to restore Barnaby, insisting that the “strip has a genuinely subtle humor which surpasses that of all others found in your publication.” If some readers don’t “appreciate this humor,” that is “insufficient reason for withdrawing it from a newspaper whose aim, we presume, is to please those of all intellectual levels.” A week later, Barnaby returned, with Wolff’s apologies.15

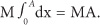

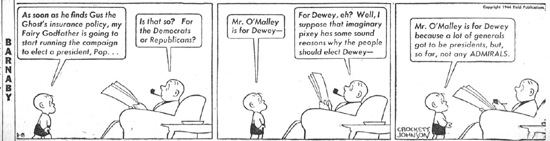

The strip’s subtle political humor gave it a wider appeal than Johnson’s New Masses work. For example, in the fall of 1944, O’Malley expresses his support for Thomas E. Dewey, the Republican nominee in the upcoming presidential election, because “a lot of generals got to be presidents, but, so far, not any ADMIRALS.” Johnson also depicts three ghosts as strong Dewey supporters: One of the ghosts, Colonel Wurst, is named for two anti-Roosevelt and isolationist newspaper owners, Colonel Robert McCormick of the Chicago Tribune and William Randolph Hearst of the New York Journal-American and several other papers. Wurst introduces another ghost, A.A., as “able to give us the direct, uncolored view of a ‘Man in the Street,’” but when A.A. advises Barnaby, “Sell short, young fellow, sell short,” it becomes clear that he is not a “Man in the Street” but an investor. Implying that Dewey’s supporters are deluded by nostalgia, Johnson has Colonel Wurst printing progressively earlier newspapers. One from 31 October proclaims “Peace in Our Time” (Chamberlain’s defense of the Munich agreement, September 1938), and by 7 November 1944, the clock has been turned back to before the 1929 stock market crash: The ghosts stroll off, singing “Happy Days Are Here Again.” Johnson thus mocks without offending: As the Bridgeport Sunday Herald’s Ethel Beckwith observed in October 1944, “Nobody gets mad. Readers of both parties think they are slyer than the cartoonist in making it out for their side.”16

Crockett Johnson, page from Barnaby and Mr. O’Malley (New York: Holt, 1944). Reprinted with the permission of the Estate of Ruth Krauss, Stewart I. Edelstein, Executor. All Rights Reserved.

Crockett Johnson, Barnaby, 8 September 1944. Image courtesy of Rosebud Archives. Reprinted with the permission of the Estate of Ruth Krauss, Stewart I. Edelstein, Executor. All Rights Reserved.

Crockett Johnson, Barnaby, 29 September 1944. Image courtesy of Rosebud Archives. Reprinted with the permission of the Estate of Ruth Krauss, Stewart I. Edelstein, Executor. All Rights Reserved.

Johnson, however, remained a supporter of Franklin Roosevelt’s reelection, lending both his name and his artwork to the Artists Committee for the President’s Birthday and to the Independent Voters Committee of the Arts and Sciences for Roosevelt (IVCASR). To promote FDR’s campaign, IVCASR published a twenty-two-page booklet containing the text of FDR’s 23 September 1944 speech to the Teamsters Union with illustrations by nineteen progressive artists. In the address, Roosevelt commented about recent Republican criticism, “Well, of course, I don’t resent attacks and my family don’t resent attacks, but Fala does resent them.” Fala was the president’s Scotch terrier, and when he learned that “the Republican fiction writers in Congress” had alleged that Roosevelt had sent a destroyer to fetch the dog, “his Scotch soul was furious. He has not been the same dog since.” Hugo Gellert drew a heroic portrait of FDR, William Gropper caricatured Republican opponents of the New Deal, Lynd Ward offered a heroic image of the American factory worker making airplanes, and Syd Hoff showed the common man donating a dollar to FDR while a fat capitalist gives a big sack of money to Dewey. Crockett Johnson drew a portrait of an indignant Fala.17

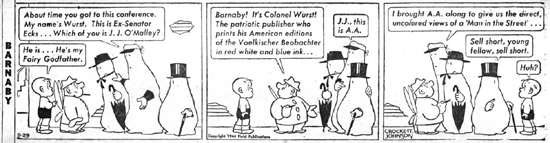

Crockett Johnson, illustrations from “Sister, You Need the Union! … And the Union Needs You!” (United Auto Workers–CIO pamphlet, 1944). Images courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution. Reprinted with the permission of the Estate of Ruth Krauss, Stewart I. Edelstein, Executor. All Rights Reserved.

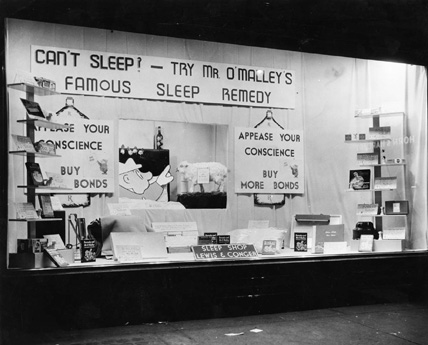

Earlier in 1944, Johnson illustrated a United Auto Workers–CIO pamphlet, “Sister, You Need the Union! … And the Union Needs You!,” that reminded women to get involved with their union and to help themselves by helping the union “make a better world.” It concluded by advising, “Get Busy in the CIO Political Action Campaign. Register and Vote!” Enlisting O’Malley in support of the war effort, Johnson also devised slogans for a War Bond display window in Lewis and Conger, a New York department store.18

Holt published Barnaby and Mr. O’Malley in September 1944 to mixed response. Even reviewers who praised the first volume now struggled to classify Johnson’s comic strip. Isabelle Mallet of the New York Times, who had called Barnaby “a series of comic strips which, laid end to end, reach from here to wherever you want to go before you die” and who found the new book engaging, could not find the right words to “pay suitable tribute. We might just as well try to fasten the Nobel Prize on a rainbow.” In Booklist, proletarian novelist Jack Conroy, whose first children’s book, a collaboration with Arna Bontemps, had appeared in 1942, concluded that Barnaby and Mr. O’Malley had “adult and adolescent appeal, rather than juvenile, but the book might be used with older children as a substitute for comic books.” Commonweal reviewed the book in a section devoted to works for “the very young.” Its review was equally confused: “Appeals to readers of all ages, though it is a rather special taste. Some like it and some do not.”19

“Can’t Sleep?—Try Mr. O’Malley’s Famous Sleep Remedy. Appease Your Conscience. Buy More Bonds.” Window display at Lewis and Conger, New York, October 1944. Image courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution. Reprinted with the permission of the Estate of Ruth Krauss, Stewart I. Edelstein, Executor. All Rights Reserved.

Johnson was also working on the final artwork for The Carrot Seed. Nordstrom thought the little boy “perfect in most of the pictures” but felt he “shouldn’t look surprised or doubtful in any of” them because he needs a “sense of sublime assurance throughout.” Johnson agreed with the suggestion and “fixed … up” the boy’s expression. He gave precise instructions to the printers to ensure that the book’s colors were exactly right: brown, red, green, and light cream, though he was not completely sure about the last one. “Omit Light Cream?,” he wrote on the chart. The printers did, and yellow appeared in the final book.20

A week after he sent in the final changes to the Carrot Seed illustrations, Dave and Ruth took the train into New York City, where, at the Hotel Commodore Ballroom, they attended a dinner honoring Johnson’s New Masses colleague William Gropper on his forty-seventh birthday. Sponsored by the Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee, the dinner featured remarks from Dorothy Parker, Carl Sandburg, and radio broadcaster Norman Corwin. In addition to Johnson, the sixty-five sponsors listed on the program included conductor-composer Leonard Bernstein; composers Aaron Copeland and Earl Robinson; lyricist E. Y. Harburg; artists Alexander Calder, Marc Chagall, Rockwell Kent, Boardman Robinson, Louis Slobodkin, and William Steig; novelists W. Somerset Maugham and Howard Fast; screenwriter John Howard Lawson; and Paul Robeson.21

At around the same time, a coalition including some of Johnson’s New Masses friends formed the Committee for Equal Justice for Mrs. Recy Taylor, and by February 1945, Johnson had joined the group. Taylor was a black Alabama woman who had been gang-raped by six white men in September 1944. Although local law enforcement could identify the men, they were not charged with the crime. Though much less famous than the Scottsboro Boys case thirteen years earlier, Taylor’s plight highlighted persistent racial injustice in Alabama, an issue that Johnson also took up in Barnaby. In November 1943, O’Malley had been elected to Congress, and a March 1944 strip had him telling Barnaby about Representative Rumpelstilskin, a blowhard who supports the poll tax, offering “incoherent shrieks about states’ rights” as a result of his “neurosis.” According to O’Malley, Representative “Rump” is “elected by only 2½ per cent of the people in his district. Other congressmen get eleven times his vote. Representing a minority group, he feels he doesn’t amount to very much.” The National Committee to Abolish the Poll Tax subsequently used this Barnaby strip in its campaign.22

Barnaby was poised for greater success. In March 1944, George Pal, creator of the Puppetoons animated movies, sought to adapt the comic strip for a short film. Johnson had already begun collaborating on a musical version of Barnaby with Ted and Matilda Ferro, residents of Cos Cob, Connecticut, who were also writing the radio serial Lorenzo Jones. For the music, they enlisted Harold J. Rome, author of the music and lyrics for Pins and Needles, a Popular Front Broadway musical about love and labor in the garment industry. Neither project came to fruition, but by the middle of 1944, a new creative team began adapting Barnaby for the stage.23

The producer behind the new venture was Barney Josephson, proprietor of Café Society, a progressive and integrated New York nightclub where the bartenders were Abraham Lincoln Brigade veterans and where Billie Holiday first sang “Strange Fruit.” For the book, Josephson brought in Michael Kanin, who had won an Academy Award in 1942 for Woman of the Year, which starred Katharine Hepburn and Spencer Tracy. When Kanin’s Hollywood career prevented him from working on Barnaby, Josephson sought New Yorker humorist S. J. Perelman. For the lyrics, Josephson enlisted John LaTouche, lyricist for “Ballad for Americans” (1940), the unofficial anthem of the Popular Front. Jimmy Savo, one of the inspirations for Mr. O’Malley, signed on to play Barnaby’s fairy godfather.24

This success gave Dave enough income to buy a home, and in February 1945, he purchased a house in Rowayton, directly across the Five Mile River from the Darien house he and Ruth had been renting. Located at 74 Rowayton Avenue, on the corner of Crockett Street, the house faced the water. He also bought the land on the other side of Rowayton Avenue so that he could moor his boat at the dock across the street.25

That spring, Harper published The Carrot Seed, which Ruth privately called The Toinip Top. The book was an immediate hit. Kirkus called it a “good humored tale” and noted that “the publishers, in choosing Crockett Johnson, creator of Barnaby and Mr. O’Malley, as illustrator, have picked the ideal person for the job.” The New York Times Book Review’s Ellen Lewis Buell thought it a “parable” that would appeal to old and young alike, “portrayed in pictures that are economical of line as the text is with words.” It quickly became a phenomenon.26

One admirer sent a copy of The Carrot Seed to the United Nations Conference on International Organization in San Francisco, where representatives from fifty countries would sign the United Nations charter that June. In August, the president of an engineering firm sent out one hundred copies to executives in many fields, who in turn sought copies to send to their colleagues and employees. The Catholic Church put The Carrot Seed on its list of recommended reading, conveying the message, “Have faith and you’ll get results.” A neighbor of Ruth and Dave’s thought it a “swell book” with a great moral: “Never trust anybody, not even your parents.” The book’s openness to a range of interpretations was key to its success.27

In the fall, Dave and Ruth moved into their own home, where they would reside for the next twenty-seven years, creating many more classic books. First, however, they would need to learn to cope with their own success.