I’ll admit, Barnaby, at times I nourish misgivings about the entire venture.

—MR. O’MALLEY, in Crockett Johnson, Barnaby, 9 April 1945

Crockett Johnson’s success brought financial security—and more work. People wrote to request original strips, ask him to donate artwork to various causes, and inquire if they might reprint Barnaby comics. Editors found Barnaby very useful for illustrating concepts.

To highlight the need to educate the public about statistics, the American Statistical Association Bulletin chose a Barnaby in which O’Malley misuses statistical methods, “fitting the data to the curve” instead of using the data to plot the curve. For a report on the wartime scarcity of cigarettes, a December 1944 Advertising Age uses a strip in which O’Malley suggests that “advertising writers” are responsible for the tobacco shortage: “They never write about anything but the FINEST tobaccos. And the superlatives can be applied to only about one percent of the crop,” leaving “ninety-nine percent of the tobacco … utterly wasted!” To accompany an article on daytime radio serials illustrated by Saul Steinberg, the March 1946 Fortune ran Dave’s 30 January 1945 comic, in which Barnaby points to a radio broadcasting the words “Sob. Sob. Sob.” He observes, “This lady sounds just like the ones on all the other programs, Mr. O’Malley.” His godfather explains that this is “a very stylized art form,” but the “tiny nuances writers and actors are permitted to inject” serve as “the basis of the devotee’s esthetic enjoyment.” To display the best of the nation’s popular culture, the U.S. Office of War Information asked for six Barnaby cartoons to feature in a spring 1945 exhibition of American cartoons in Paris. Johnson sent six original strips.1

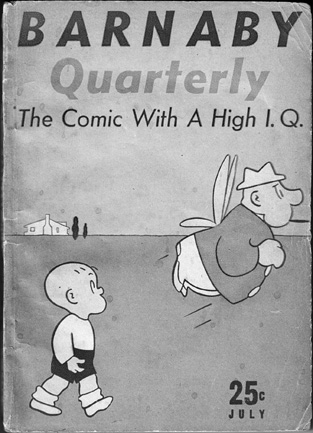

Adapting Barnaby for the stage was proving trickier than anticipated, and changes in script, writers, and cast threatened to delay production. Barnaby did, however, make its radio debut on 12 June 1945. On the second half of that day’s Frank Morgan Show, Morgan (best known for portraying the title character in MGM’s Wizard of Oz) played O’Malley, and seven-year-old Norma Jean Nilsson played Barnaby. No further episodes aired. At the same time, Johnson was cranking out six Barnaby strips each week, imprisoned by his own perfectionism: “I never feel that I can let down. If I did, the stuff wouldn’t get to be just mediocre; it would be terrible.” Thinking that quarterly deadlines might allow him to take some time off, he sought “to do strips that were syndicated only in quarterlies.” The first issue of the Barnaby Quarterly made its debut in July 1945, reprinting Barnaby’s adventures from the first five months of the year.2

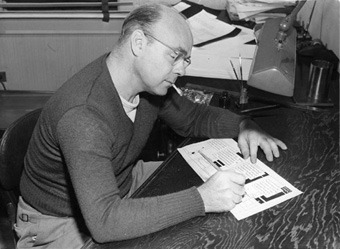

Crockett Johnson posing with the Barnaby strip of 22 April 1944. Image courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution. Reprinted with the permission of the Estate of Ruth Krauss, Stewart I. Edelstein, Executor. All Rights Reserved.

Ruth Krauss had more time to think but was out of ideas. Even before The Carrot Seed was published, she had begun contemplating next her book but found herself uninspired. She rummaged through “some cartons full of old manuscripts” that she kept “in honor of an occasion like this” and pulled out on story about a boy who imagines that he’s a superhero. But “the story was around ten thousand words long,” far too long for a picture book, and although “the idea seemed clear, … it needed a lot of rewriting.”3

Krauss rewrote the story over and over but was not satisfied. She noticed that when she told the story to friends, they laughed. To try to capture that comic tone, she decided to write the story the same way that she spoke it. Pleased with her inspiration, she took the manuscript to Ursula Nordstrom at Harper, who laughed and immediately said, “I’ll take it.” She wanted some changes, though. She thought it should be “built up” here and there, and although it was now only fifteen hundred words, Nordstrom thought it was still too long.4

Crockett Johnson, cover of Barnaby Quarterly, July 1945. Reprinted with the permission of the Estate of Ruth Krauss, Stewart I. Edelstein, Executor. All Rights Reserved.

For assistance in revising the story, Krauss brought the manuscript to the Bank Street Writers Laboratory in July 1945. Established by Lucy Sprague Mitchell in 1938, the laboratory helped authors create books that recognized that young children’s speech reflects their “immersion in the here-and-now world of the sensory realm,” that children learn language not to communicate but because it is fun to play with words, and above all, that adults must trust the child’s imagination.5

Ursula Nordstrom, n.d. From Leonard Marcus, Margaret Wise Brown: Awakened by the Moon (1992; New York: Quill/Morrow, 1999). Reprinted by permission of HarperCollins Publishers.

That trust came naturally to Krauss because she took children’s ideas seriously. According to Mischa Richter’s son, Dan, “She just talked to children as though they were just other people.” She saw him as a friend, not as a seven-year-old, and took him to see the original theatrical release of The Razor’s Edge (1946). Recalled Richter, “Most adults are like these faces that are bending over, talking to you in sort of abridged English,” but Ruth “didn’t talk down to me or baby me at all.” Her treatment of children as equals made the Bank Street Writers group a good fit for her.6

She met with the Bank Street group and “let the whole bunch go to town on” her manuscript. Krauss was “wary of the general prejudice against comicbooks,” and Nordstrom had suggested that the boy’s superhero costume be changed because “the American Library Association will object. And many parents will object.” To avoid this problem, Krauss decided on a “mixed-hero costume”—the boy would wear aspects of different heroic costumes, such as “an Indian Chief’s hat,” a “football suit with big padded shoulders,” and “cowboy boots with spurs.”7

The Bank Street writers had different ideas. One person said, “If I were a child and someone gave me an Indian hat and didn’t finish up the Indian costume, but gave me something else instead, I’d be awful mad.” Another said, “He ought to be a sort of glorified policeman.” After three hours’ discussion, Krauss got the sense that “the suit should be like a supersuit, but not the supersuit; that is, it should be generally glorious and symbolic of ability—but nothing specific. This was very helpful.” She went home to revise some more.8

The mid-1940s also saw the beginning of Ruth and Dave’s long and close relationship with Phyllis Rowand, her husband, Gene Wallace, and their daughter, Nina, who was born in New York City in November 1945. The following March, four-month-old Nina took her first trip to “the country”— Connecticut. The members of the Rowand-Wallace family piled into a car with Simon and Schuster vice president Jack Goodman; his wife, Agnes, an editor; and their Great Dane, Sam, and drove up to Rowayton. That June, Gene, Phyllis, and Nina moved up to Rowayton, renting the Goodmans’ cottage at 89 Rowayton Avenue, just four houses up the street from Ruth and Dave.9

Wallace, a World War II veteran and naval architect, shared many of Dave’s interests: Both men liked to sail, enjoyed making things with their hands, and played a good game of chess. They spent many an afternoon working on their boats or smoking their pipes and chatting over the chess board. Rowand, who wrote for Woman’s Day and created ads for Houbigant Perfume and other clients, had been thinking about branching out into children’s books. Even before moving to Rowayton, she had begun collaborating with Ruth on The Growing Story, a tale of a little boy who notices that the grass, flowers, and trees are growing. After learning that chicks and a puppy will also grow, he asks, “Will I grow, too?” As the year passes, he notices that the plants and animals are growing but cannot see any changes in himself. When he puts on his winter clothes, however, they have become too small. He runs out into the yard to tell the chickens, “I’m growing too.”10

Though Ruth and Dave did not raise chickens, their new home definitely felt like the country. Located in South Norwalk, Rowayton was a nineteenth-century oystering community that had become a popular summer destination for vacationers, artists, and progressives. Dave liked to call the tiny village “the Athens of South Norwalk.” Ruth and Dave soon became close to other neighbors in addition to Wallace and Rowand. Actor Stefan Schnabel and his wife, singer/actress Marion Schnabel, and their children became good friends. Sculptor Harry Marinsky and his partner, Paul Bernard, moved in just across Crockett Street from the Johnson-Krauss house. The presence of an openly gay couple did not bother Ruth and Dave or anyone else in the neighborhood. However, as an out gay couple, Marinsky and Bernard were atypical. Johnson and Krauss’s other gay friends—Ursula Nordstrom and Maurice Sendak—did not make their sexuality public knowledge. In contrast, Marinsky and Bernard were living as a married couple some sixty years before Connecticut recognized gay marriage.11

Fred Schwed Jr., Harriet Schwed, and Crockett Johnson, n.d. Image courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution. Reprinted with the permission of the Estate of Ruth Krauss, Stewart I. Edelstein, Executor. All Rights Reserved.

Dave and Ruth also became particularly close to neighbors Fred Schwed Jr., a magazine writer and former stockbroker, and his wife, Harriet. Fred Schwed was the author of the satirical Where Are the Customers’ Yachts?; or, A Good Hard Look at Wall Street (1940), which expressed the same sort of sentiments present in the brilliant satire of Wall Street that Johnson presented in Barnaby from February to May 1945. O’Malley becomes a Wall Street tycoon not through shrewd investing but because of the speculative nature of market economics. By having a character whom adults regard as imaginary use purely imaginary assets to become a wealthy financier, Johnson blurs the line between real and imagined to suggest that free-market capitalism is inherently precarious and that Wall Streeters’ romantic view of the marketplace ill equips them to differentiate between profitable fantasies and market realities. As Schwed wrote, “The notion that the financial future is not predictable is just too unpleasant to be given any room at all in the Wall Streeter’s consciousness.” Those who work on Wall Street “are all romantics, whether they be villains or philanthropists. Else they would never have chosen this business which is a business of dreams.”12

The Barnaby episode begins when O’Malley phones stockbrokers to ask about purchasing 51 percent of Hunos-Wattall Ltd. (pronounced Who-knows-what-all) but unknowingly talks only to an office boy. He thinks O’Malley is a “bigshot” and word gets out that “international financier” O’Malley is starting a new company. Since no one wants to admit that they have never heard of O’Malley, investors back his company, real people begin running it, and the stock soars. But speculation becomes O’Malley Enterprises’ undoing: When O’Malley offers to pay cash to tailors Cuttaway and Sons for his trousers, they are insulted that he does not charge the purchase to his account. Word spreads that his credit is no longer good, and the stock plummets, bringing down the company with it. Only a few years after the end of the Great Depression and with many people worried that the conclusion of World War II might end wartime prosperity, Johnson was making a very serious point about the instability of capitalist economies. As O’Malley says about a week prior to O’Malley Enterprises’ collapse, “I’ll admit, Barnaby, at times I nourish misgivings about the entire venture.”13

As the country drifted to the right, the popularity of market-driven economics revived. The death of President Franklin Roosevelt in April 1945 and the end of the war four months later marked the beginning of the end of the Popular Front. Its decline did not change Johnson, who continued to support progressive ideals. When the Independent Voters Committee of the Arts and Sciences for Roosevelt became the Independent Citizens Committee of the Arts, Sciences, and Professions (ICCASP) in December 1944, Johnson remained an active member, regularly attending meetings of the group’s Norwalk chapter and winning election to the branch’s executive committee in January 1946. At the national ICCASP’s annual meeting in New York the following month, he was elected one of thirty-two members of the group’s board of directors, along with Leonard Bernstein, Duke Ellington, Gene Kelly, Langston Hughes, Howard Fast, Moss Hart, Lillian Hellman, John Hersey, Bill Mauldin, Hazel Scott, and Orson Wells. One of the ICCASP’s goals was passage of the Wagner-Murray-Dingell Bill, which promised national health insurance and money devoted to building more hospitals. To aid that cause, Johnson illustrated the Physicians Forum’s For the People’s Health, a pamphlet supporting the measure.14

Crockett Johnson, cover of For the People’s Health (New York: Physicians Forum, 1946). Image courtesy of Toby Holtzman. Reprinted with the permission of the Estate of Ruth Krauss, Stewart I. Edelstein, Executor. All Rights Reserved.

That bill met defeat, but some of Johnson’s causes thrived. In 1945, he signed on to the Committee for the Reelection of Benjamin J. Davis, a Communist serving on the New York City Council who won reelection by a wide margin. That same year, Johnson joined Davis in supporting the End Jim Crow in Baseball Committee, whose members also included Rockwell Kent, Paul Robeson, and Langston Hughes. In August 1945, at Stamford’s Russian Relief Headquarters, both Johnson and Krauss served as sponsors and participants in the Books for Russia Committee of the American Society for Russian Relief. Krauss’s involvement was unusual: She rarely expressed her political convictions by joining organizations.15

The story about the boy dreaming of being a superhero acquired a title, The Great Duffy, and Krauss hoped that Johnson would provide illustrations, as he had for The Carrot Seed. When his other commitments prevented him from doing so, Krauss turned to Mischa Richter, now a successful New Yorker cartoonist. Johnson, however, did the layout, chose the type (fourteen-point Bodoni bold), and created some sample drawings.16

Mischa Richter, cover of Ruth Krauss, The Great Duffy (New York: Harper, 1946). Image courtesy of the Northeast Children’s Literature Collection, Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut, Storrs. Used by permission of the Estate of Mischa Richter.

Perhaps inspired by Johnson’s efforts to bring Barnaby to the stage, Krauss drafted a movie treatment for The Great Duffy. The film would have “the usual blacks and greys to symbolize reality” and “Technicolor to symbolize imagination.” Each time six-year-old Duffy (renamed Buzzie in the movie version) encounters a major disappointment, he launches into a fantasy. Just before each daydream, the film dramatizes his feelings of “being very little in a very big world” by making everything larger: “Adults would enlarge to giants, ordinary furniture would take on architectural and engineering qualities.” As the film switches to Technicolor, objects return to their normal size and Buzzie drifts into his fantasy world. After several such episodes, the movie concludes with him facing the challenge of crossing the street by himself but not retreating into daydreaming: To Buzzie, dealing with traffic was “as adventurous as his daydreams.” He succeeds and feels “a little surer of himself.”17

Krauss’s adaptation of The Great Duffy expresses a deep understanding of young people’s relative powerlessness in the world, a theme that remained on her mind in the fall of 1945. On 31 October, she visited Nordstrom to discuss several ideas for future books, including a short chapter book “on being small” and a picture book on the same subject. Krauss also proposed a collaboration with child psychologist Stephanie Barnhardt to edit a series of books covering “common problems,” such as “fear of the dark, first day at school, refusal to eat, the new baby in the family, temper tantrums, etc.” Nordstrom demurred, saying that Margaret Wise Brown’s books already “did this sort of thing subtly and artistically”: Brown’s Night and Day (1942) addressed the fear of the dark; Little Chicken (1943) concerned the first day of school; and The Runaway Bunny (1942) offered the “reassurance of mother’s love.” Krauss pressed her idea, arguing that a series “sponsored by well-known educators would sell well,” and Nordstrom acquiesced. Krauss also proposed a book inspired by her husband’s tendency to let his dogs be themselves that Nordstrom thought “could be extremely funny and good.” The tale about “Why the Dog Is Man’s Best Friend” shows a puppy gradually “taking over a human’s entire life, home, time, money.”18

While Krauss was gearing up to write more stories, Barnaby was wearing Johnson out. In early November 1945, he met with Ted Ferro and Jack Morley to see if they would take over the strip. Johnson would sit in on story conferences and share in the strip’s profits, but he wanted Ferro to take over writing and Morley to take over drawing. They agreed. Johnson was earning 50 percent of the net receipts of Barnaby reprints, with the other half going to PM. Johnson reduced his share to 20 percent, giving Ferro and Morley 15 percent each. Beginning on 31 December 1945, Crockett Johnson’s name no longer appeared on Barnaby.19