So, before he went to bed, he drew another picture.

—CROCKETT JOHNSON, A Picture for Harold’s Room (1960)

Creatively, 1958 began very well for Ruth Krauss and Crockett Johnson. She was working on a book based on the artwork she had collected from children at the Rowayton public schools over the past six years. One child had drawn “Girl with the Sun on a String,” a bright round yellow circle with yellow lines radiating outward; one line ran all the way down into the grip of a little girl’s hand. A drawing of a white circle against a darker background bore the caption “A Moon or a Button.” Instead of A Book of First Definitions (the subtitle of A Hole Is to Dig), this would be A Book of First Picture Ideas.

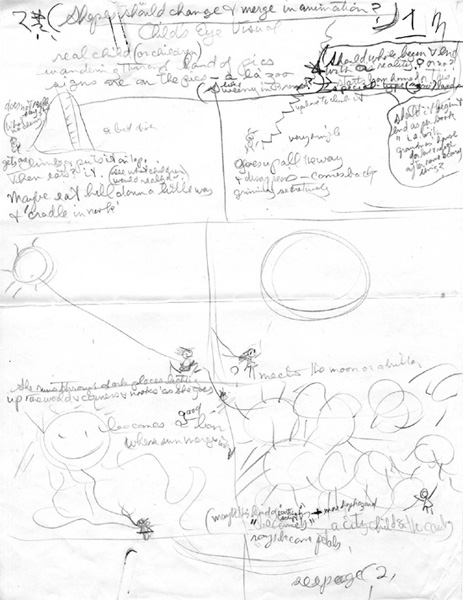

As with A Hole Is to Dig, Krauss repeatedly arranged and rearranged her ideas. Over three pages of notes titled “Child’s Eye Visual,” she created a layout of the illustration as a narrative, with each scene loosely suggesting the next. Krauss’s associative logic creates a story that unfolds like a dream.1

Though recovering from a sprained ankle in early 1958, Johnson wrote three new stories and rewrote another. As Ursula Nordstrom told him, “You certainly are hitting on all 24 cylinders these days.” Joining the roster of classic Crockett Johnson characters were Ellen, an imaginative preschooler, and a stuffed lion, her best friend and confidant. The lion is skeptical, unsentimental; Ellen is relentlessly creative, inventing adventures for herself and her lion, often a reluctant participant. Similar to Bill Watterson’s Hobbes nearly thirty years later, the lion’s status as stuffed animal is never in question, but his ability to think independently varies. He appears to be both animated by Ellen’s imagination and able to arrive at his own conclusions, which tend to contradict hers. When she thinks he is sad and tries to sympathize with him, he tells her, “All this talk of sympathy for my feelings is silly, Ellen. I’m a stuffed animal.”2

What Harold achieves with his purple crayon, Ellen does with words and props—she imagines for herself a role as malleable as the universe she creates. Like Barnaby’s friend, Jane, Ellen does not limit herself to “girlish” activities but moves easily between feminine and masculine roles. When the story “Fairy Tale” begins, Ellen is the “fairy godmother”; a few paragraphs later, she has become “the invincible knight”; near the end, she turns into “the lovely princess”; and she ends up as Ellen. Johnson also playfully shifts the narrative voice back and forth between Ellen’s perspective and the view of a slightly bemused observer—sometimes in the same sentence. “Fairy Tale” begins, “Once, twice, and thrice the beautiful fairy waved her wand and, before she spoke, she took another bite of muffin covered with raspberry jam.” Later, “the knight” is “eating jam and muffin as she surveyed the besieging army across the wide moat.” Though the shifts from Ellen to the mildly ironic narrator do invite a smile at her games, Ellen’s Lion treats her wishes with sympathy. Unlike Russell Hoban’s Bedtime for Frances (1960), in which Father uses the threat of “a spanking” to silence Frances’s imagination, Ellen’s Lion celebrates a little girl’s inventive mind.

Ruth Krauss, “Child’s Eye Visual,” early layout for A Moon or a Button (New York: Harper, 1959). Image courtesy of the Northeast Children’s Literature Collection, Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut, Storrs. Reprinted with the permission of the Estate of Ruth Krauss, Stewart I. Edelstein, Executor. All Rights Reserved.

In February, Johnson sent the first four Ellen stories to Nordstrom “in the hope that you will have time in the next week or two to look at it and let me know if it seems to you to be anything for children (or anything for anybody).” If she liked these stories, he would write more. Both Nordstrom and Susan Carr loved them: Carr thought “these Ellen and lion stories are absolutely enchanting, and will make a marvelous book. I am most eager to see the rest of the ms, and have no criticism at this point.” During March, he wrote another seven stories.3

Johnson was also rewriting The Frowning Prince, redoing the color separations for The Blue Ribbon Puppies, and sketching plans for Harold’s Circus, the fifth purple crayon adventure. On 7 April, he wrote, “I haven’t had anything to do for a month except make up things in my head,” suggesting that creating stories came easily to him. He had spent that time “sketch[ing] out a another ‘Harold’ book that I think will work out pretty well. It can be called ‘Harold’s Circus’ maybe.” In a sentence, he then describes the entire plot of what would become Harold’s Circus. Would Harper “want another ‘Harold’ book for 1959?” Dave asked. Nordstrom replied that Harold’s Circus could “be one of the best” and suggested making it a spring 1959 book: “If we do The Frowning Prince in the same publishing season it can’t make too much of a problem I am sure because they are both so different.”4

The Frowning Prince is different. Readers accustomed to smiling (or at least benign) expressions on the faces of Crockett Johnson’s characters may be surprised by the prince’s determined frown. When a king begins reading a storyard, bowing low again. “For one, your father has just said so, and he is the king.”

“Tell us one of the other reasons,” said the prince.

The grand wizard took off his glasses and polished them carefully. When he spoke again it was to the king.

“Tell me, your majesty, just how did all this arise?”

“Yesterday I borrowed a book from you,” said the king. “A fairy tale.”

“Yes, I remember it was the last book-of-the-moon selection. One arrives every perigee,” said the grand about a princess with “an irresistible smile,” his son proclaims, “Nobody could make me smile.” Determined to prove his son wrong, the king calls in jesters, jugglers, and even the grand wizard. The queen, however, understands that this battle of wills merely encourages the prince: She tells the king, “Try not to let it bother you” and tells the prince, “It will go away,” patting his head. Johnson’s story playfully pokes fun at its fairy tale status: When the wizard suggests summoning the smiling princess from the book, the king tells him not to bother because the “book said the princess lived once upon a time.” The wizard reminds him, “This is once upon a time.” When the king points out that “the princess also lived in a faraway land,” the wizard reasons, “This kingdom of yours is a faraway land, your majesty. And if two lands are both far away, they must be close to each other.” Subtly advancing a theme of peace, the king must “call off the wars” with the neighboring kingdom to invite the other king and queen and their daughter for a weekend visit. Sure enough, the prince does at last smile, though the tale never indicates whether the cause is the princess’s smile or the court’s concession that the prince’s frown is “immovable.” The royal couples find that they have “much in common and enjoyed each other’s company immensely,” and, with the two kingdoms at peace, the “happy subjects” go back and forth between countries as well.

Crockett Johnson, page from The Frowning Prince (New York: Harper, 1959). Reprinted with the permission of the Estate of Ruth Krauss, Stewart I. Edelstein, Executor. All Rights Reserved.

Harper bought those books, but Johnson also wrote one that either he never submitted to Nordstrom or Harper turned down. Will Spring Be Early? Or Will Spring Be Late? won a contract from Thomas Y. Crowell, publishers of the Crockett Johnson–illustrated Mickey’s Magnet. On 2 February, the conscientious Groundhog prepares to make his prediction and must verify that spring will be early. As he listens and smells for the sun, a passing Artificial Flower Co. truck interferes with his senses. When he finds an artificial flower that has fallen from the truck, he thinks it real and shouts, “Spring! It’s here now!” He rushes off to tell the Badger, Dormouse, Rabbit, Skunk, Chipmunk, Squirrel, Raccoon, Bear, and Pig. Echoing Krauss’s The Happy Day, the animals dance in a circle around the flower. The Pig does not join in but instead chomps the flower and then announces, “The leaves are paper. The stem is wire. The petals are plastic. And the lot of you will freeze out here.” He makes his own prediction: “It’s going to snow.” In a reversal of The Happy Day, this flower growing in the snow is not a sign of spring. The snowstorm begins, the “Groundhog [begins] to creep quietly away,” and the disappointed animals seek to assign fault:

“We were all so happy,” the Dormouse said, “until the Pig came and chewed the flower.”

“Precisely!” shouted the Bear. “And now we’re cold and miserable and ridiculous! It’s perfectly clear who’s to blame!”

The book ends with the narrator’s summation: “They blamed the Pig, of course.” The Groundhog continues to make his predictions each February, and Johnson’s comic twist evokes a laugh of recognition at the human tendency to blame the messenger.

While continuing to write, Johnson and Krauss also oversaw foreign editions of their earlier books and promoted their work at home. When Constable and Company printed Harold and the Purple Crayon in the United Kingdom, the publisher made some changes in color, which in turn changed the line of the drawing. Now that Constable was planning to publish A Hole Is to Dig, Krauss was wary. Maurice would check on the colors himself when in England in late August 1958. If the publisher felt that he and Krauss were “being overly precious about this book,” she wrote, “well, we are. We love the book. We both feel that its physical appearance—which was experimental in form … —is important to its appeal as a book.” She, Sendak, Nordstrom, Johnson, and Harper’s production department had “worked hard on the physical make up of the book,” and they wanted “the English edition to be a lasting one—if it ever comes about.” Either Krauss and Sendak’s demands deterred Constable, or the publisher was not able to meet them. A Hole Is to Dig was not published in the United Kingdom until Hamish Hamilton’s 1963 edition.5

In the United States, Krauss and Johnson made appearances to promote their work. They celebrated National Library Week at the Rowayton Library on 18 March 1958, joining other local writers such as New Yorker cartoonist Carl Rose, magazine writer John Sharnick, and journalist Leonard Gross, whose God and Freud had just been published. Many of the authors on hand were Johnson-Krauss friends: Fred Schwed, Phyllis Rowand, Aggie Goodman, and Jim Flora, who had moved to Rowayton in 1952 with his wife, Jane, and their children. When rock-and-roll records’ preference for photographic jackets pushed his bright, angular jacket art out of favor, Flora began creating colorfully offbeat children’s books, among them The Fabulous Fireworks Family (1955) and The Day the Cow Sneezed (1957). He and Johnson shared a background in typography and magazine design plus interests in playing with language, boats, and humor.6

Johnson’s subversive wit emerged in his response to critics who complained that Harold’s decoration of blank white pages inspired young readers to draw in books. A librarian from Ontario’s Niagara Falls Public Library wrote of “the havoc” Johnson had caused, submitting as evidence the final two pages from Harold’s Fairy Tale, generously embellished by a young reader’s crayon. She added, “We have been accused of becoming a passive audience, it must give you pleasure to have written books which inspire action.” Johnson was indeed pleased to inspire creativity, but he had heard this particular complaint one too many times and drafted a long, satirical reply. Although he was very aware of “the scourge of crayon vandalism,” she had “been taken in by the enemy”:

Your letter reveals that you have no grasp of the problem that faces us and that you know very little about our opponents. Their organization, on the surface, is so apparently loose-knit and casual that I daresay you have not recognized it as an organization at all. Its members are disarmingly young, which tends to lead a superficial observer to laugh at the assertion that it systematically has been destroying the world’s literature for centuries…. The average crayon vandal seems childlike and innocent, and actually he is. But there are millions like him, each with his small urge for destruction developed and channeled by the efficient hard core of the organization, by its precocious and dedicated leaders.

In fact, the Harold books were part of Johnson’s plan to stop crayon vandalism: “A ‘Harold’ book invites an average vandal to indulge himself vicariously, to sublimate his urge. Often the effect is so long-lasting that the next two or three books that fall into his hands are spared. When any such lapse occurs the organization [decides that it] can no longer depend on member and he, finding himself with few assignments, usually begins to lose interest, and often he drops out. The object of course is to decimate the enemy’s ranks, ultimately to make the dread organization of crayon vandals a thing of the past.” He concluded, “But it is much too soon to talk of total victory…. It will be a matter of years, probably, before world statistics on crayon marks per page, for the first time in history, show a noticeable downward trend. But the day will come!” Having vented his feelings, Johnson sent the letter to Nordstrom but not to the complaining librarian.7

The intensity of Johnson’s response is noteworthy because he tended to be modest about his work. He frequently worried, for example, that his characters all looked the same, and his concerns were not unfounded: The boy from The Carrot Seed could be a brother of Barnaby or Harold. However, what Johnson saw as an aesthetic weakness is actually a strength. His clean, precise style depicts only the details the story requires, omitting all else. In the words of R. O. Blechman, “Simplicity shows respect for the viewer. You don’t give more than what the mind needs, nor less than what the eye deserves.” Johnson’s effective, efficient mode of storytelling looks simple but is in fact the result of rigorous perfectionism. As Johnson once said, “Never overlook the art of the seemingly simple.”8

But Johnson’s art was often overlooked. Though the Harold series earned favorable reviews and sold well, Johnson’s other children’s books received little critical attention. One reason is that until recently, the Caldecott Committee has ignored cartoonists. In the 1950s, the award went to such beautiful watercolors as Ludwig Bemelmans’s Madeline’s Rescue (1954), Marcia Brown’s Cinderella (1955), and Robert McCloskey’s Time of Wonder (1958). Sendak’s magnificent india ink illustrations for Where the Wild Things Are would win in 1964. Dr. Seuss got Caldecott Honors in 1948, 1950, and 1951 but never received the top prize. Not until 1970, when William Steig won for Sylvester and the Magic Pebble, did a cartoon artist win the Caldecott Medal. The following year, Sendak’s In the Night Kitchen (1970), inspired by Winsor McCay’s turn-of-the-century Sunday strip Little Nemo in Slumberland, won a Caldecott Honor, and the medal subsequently has gone to several artists who either use a comic style or deploy the narrative techniques of comics. Though the Caldecott eluded him, Crockett Johnson received some recognition in 1958 when the American Institute of Graphic Arts awarded him a Certificate of Excellence at its Children’s Book Show. He designed the poster for the New York Herald Tribune’s spring 1958 Children’s Book Festival, depicting Harold standing atop a stack of purple-crayon-created books and reaching up over his head to draw a moon.

Sendak remained a regular visitor to the Krauss-Johnson home. He so loved his weekends there that he considered his time in Rowayton his “precious life.” That said, working with Krauss could be trying. He would paste an illustration in one place, and she would rip it off the page and place it in another. On many occasions, their fights brought him near tears. Johnson would step in to referee, quietly making a suggestion about the composition of the page over which Krauss and Sendak had been arguing. Sendak believes that “part of her fury was educating me, the dumb Brooklyn kid, into a more interesting human being. She was determined that I have more insight, that I think higher.” In contrast, Johnson was a welcoming, gentle presence who “looked just like everything he drew. The face was Barnaby. And yet it was a beautiful face…. He was not a beautiful man, but it was a beautiful face.” The two men sat by the fireplace and talked about books, with Johnson offering reading suggestions. Since Sendak had been reading Tolstoy, Johnson suggested that he try Dostoevsky and Chekhov. There was no test; Johnson never checked to see that Sendak had read the recommended books. Rather, he simply wanted to give his friend an opportunity to expand his intellectual horizons.9

Arriving one Friday, Sendak headed upstairs to begin unpacking. Happy to be in his room, with windows that looked out onto the water, he was shocked to discover that he had not packed his work for Krauss’s book. “It was one of those Freudian moments where clearly I just wanted to be with them,” he recalled. Embarrassed and nervous, he went downstairs and to explain that he did not have his work. Krauss was furious. “What the hell are you here for?,” she shouted. “What do you think this is, a hotel, for Chrissake?” Johnson swiftly intervened, saying, “Maury can come when he likes. And I think I’m going to take him for a sailboat ride.” He understood Sendak and was happy to accept him as their guest and friend. Krauss also understood but was not going to let Sendak know that. As he and Johnson walked out of the house and down to the dock, Sendak was so grateful that he didn’t mention his fear of water. He thought, “If I drown, at least I’m drowning with Crockett Johnson.” Sendak was safe with Johnson, but his “precious life” in Rowayton was ending.10

Krauss loved mentoring young people, helping them get started in their careers. By the latter half of the 1950s, however, Sendak was doing well professionally and was much in demand as an illustrator. Between 1953 and 1958, he illustrated between three and six books a year and published two books of his own. Krauss was happy for him but felt that he no longer needed her help.11

She began cultivating a professional relationship with another young gay artist she admired, Remy Charlip. Krauss loved his illustrations for David’s Little Indian (1956), a Margaret Wise Brown book, and wrote him a fan letter suggesting that he contact her. Charlip knew A Hole Is to Dig and especially liked I’ll Be You and You Be Me. He telephoned Krauss, and she invited him to visit. When he arrived, she explained the concept for her Book of First Picture Ideas. She had by then abandoned her attempt at a linear narrative, instead structuring it as a series of scenes, the same format A Hole Is to Dig followed. Charlip liked her idea and set to work creating full-color illustrations.12

Enthusiastic about his pictures, Krauss brought Charlip to see Nordstrom and Carr at Harper. Charlip put his colorful paintings on Nordstrom’s desk. Nordstrom was irritated by Krauss’s insistence on working with another young, inexperienced artist, and the editor’s first response was “No color! Anyway, it’s black-and-white that separates the men from the boys.” Losing her temper, Krauss leaned over Nordstrom’s desk, gathered Charlip’s artwork in her arms, and flung it into the trash. Crying, Krauss then ran out of the office toward the ladies’ room. Nordstrom ran after her. In the end, Nordstrom agreed to have Charlip as illustrator, though he would have to work in black and white. But she was particularly irritated by Charlip’s insistence that the book be in A Hole Is to Dig size: “It will look as though you are imitating Krauss and Sendak, and enough other publishers do that these days without Harper getting into the game.” Nordstrom did not want A Moon or a Button to detract from Philosophy Book, the “companion book” to A Hole Is to Dig on which Krauss and Sendak were working. When Krauss had suggested that project four years earlier under the title New Words for Old, Nordstrom had been lukewarm, but she had now agreed to publish it, and it was slated for Harper’s fall 1959 list.13

Delays on Harold at the North Pole almost made it miss Harper’s fall 1958 list, but it came out in time for the holiday season. Reviews were again laudatory, with Kirkus calling it “a whimsical holiday treat” and the Oakland Tribune describing it as “just as funny” as earlier Harold books. Only the New York Times Book Review was critical, having “expect[ed] more ingenious of Harold.” The positive reviews were welcome news to Johnson. His attempts to market the four-way adjustable mattress had failed, but his career as a children’s author was going well.14

Harold at the North Pole did not prove as popular as the other books in the series and ultimately went out of print. Figuring out how to sell Crockett Johnson’s books’ sly humor was sometimes challenging. For all his concerns about how well Harper was marketing his work, Johnson was not always sure which age group would want to buy his stories. After Johnson finished the manuscript of Ellen and the Lion, Carr and Nordstrom asked for a better title. He offered Talks with a Stuffed Lion because it “is as direct and descriptive a title as I will come up with and, … I kind of like it.” Although he recognized that such a title “may not sell,” “that is not important.” At least a few buyers, he thought, “will make a fond connection with ‘Talks with the Reverend Davison’ and the old inspirational and sex misinformation books of fifty years ago, which shall sufficiently delight us all.” Carr found this title “direct” but “also flat” and asked him to do better. When he came up with only Ellen and the Lion and Ellen’s Lion, Johnson proposed choosing the less ordinary of the two: “If there aren’t quite as many books called ’s Lion as there are and the Lion how about calling the fall book Ellen’s Lion instead of Ellen and the Lion?” Though it is impossible to know whether the title Talks with a Stuffed Lion would have helped, sales of Ellen’s Lion did not meet Harper’s expectations.15

Krauss was pleased to find resonances between her work in children’s books and “serious” art. Coming across James Thrall Soby’s Arp (1958), she was struck by the similarities between Jean Arp’s art—especially his Moustache Hat (ca. 1918), a visual combination of the two title items—and the art for A Moon or a Button. Her awareness of the continuities between the avant-garde and her own work not only speaks to her ambition to write for adults but also stems from her frustration with critical condescension toward children’s literature.16

The persistence of this attitude in the Authors Guild annoyed the members of its Children’s Division and had been irritating Krauss since she had joined the group in the 1940s. In 1948, recalling a guild discussion on this subject that nearly became a fight, Krauss wrote, “The whole field of books for children bears somewhat of the same status accorded children themselves in our culture. Even though they are felt to be greatly desirable, they are still look[ed] down upon.” Children’s writers were paid less, as were the staffs of each publisher’s juvenile division. A possible reason, Krauss thought, was that “except for a very few men, the publishers [of children’s books] are women, and this is also true in greatest measure the writers.”17

A decade later, some of the guild’s left-leaning children’s writers began to discuss the less remunerative book contracts offered those who wrote for a young audience. In 1959, they formed an informal caucus called the Loose Enders. According to Julia Mickenberg, the group “began to meet periodically for dinner, whenever they felt at ‘loose ends,’ and collectively they became an important force in the field.” Regular members included Krauss and Johnson’s old friends Herman and Nina Schneider and Mary Elting Folsom and Franklin “Dank” Folsom. Other core members included William R. Scott editor May Garelick and Scholastic’s Lilian Moore, Beatrice Schenk de Regniers, and Ann McGovern. These editors also wrote for children: de Regniers’s The Giant Story (1953) and What Can You Do with a Shoe? (1955) featured illustrations by Maurice Sendak. Krauss attended the Loose Enders, but as group member Leone Adelson recalled, “not regularly, because Ruth never did anything regularly.” Johnson attended only rarely.18

Though the members’ politics varied, all leaned left. As Mary Elting Folsom explained, that some were “more radical than others” was not an issue: “We just took it for granted that each of us shared with the others what I can only call a sort of basic liberal code.” Mickenberg notes that some Loose Enders turned to children’s books because McCarthyist purges had forced them out of teaching or other jobs. Others, however, turned to the field “not because other avenues had closed to them but simply because they discovered they liked to write for children.” But all Loose Enders “were opposed to the war in Korea and, later, the war in Vietnam. All were deeply concerned about the effects of racism upon children.”19

The Schneiders were perhaps the most financially successful of the Loose Enders, thanks to the National Defense Education Act, which created a market for their science books. Underwritten by that money, parties at their 21 West Eleventh Street brownstone in New York attracted an elite crew of artists and intellectuals, including Krauss and Johnson; Jules Feiffer; poets Stanley Moss and Stanley Kunitz; novelist Philip Roth; abstract painters Giorgio Cavallon, Linda Lindeberg (Cavallon’s wife), and Mark Rothko; illustrator Mary Alice “Mell” Beistle (Rothko’s wife); and electronic music pioneer Vladimir Ussachevsky and his wife, Betty Kray, director of the Academy of Poets. Mingling with other culturally important people and friendship with Nina Schneider, who also wanted to write for adults, nurtured Krauss’s dream of writing for older readers.20

In January 1959, A Moon or a Button was going to press, but Krauss was making no progress on Philosophy Book. “These damn books of this sort of feeling or essence-of-something-or-other are truly difficult,” she wrote to Nordstrom. A book of this type “just has to develop by itself.” More important, Krauss’s mind was no longer focused on this project. She wanted to be a poet.21