Modern art … non-representational forms. A development that puzzles the uninitiated.

—MR. O’MALLEY, in Jack Morley and Crockett Johnson, Barnaby, 11 March 1949

On the afternoon of 5 April 1967, Crockett Johnson and Ruth Krauss arrived at the Glezer Gallery, 271 Fifth Avenue, New York. He wore a dark shirt, with a lighter tie and jacket. She wore a simple necklace, a light-colored, loose-fitting dress, stockings, and shoes that were formal but not entirely comfortable. At 5:00, invited guests, mathematicians, and the press began to arrive. A mere sixteen months after deciding to pursue painting, Johnson was having his first show, Abstractions of Abstractions: Schematic Paintings Deriving from Axioms and Theorems of Geometry, from Pythagoras to Apollonius of Perga, and from Desargues and Kepler to the Twentieth Century.1

If he was nervous, the photographs do not betray any anxiety. Johnson grins broadly at the camera, lights a cigarette, talks with the guests: Jackie Curtis (who took the photos), Jimmy and Dallas Ernst, Shelley and Jackie Trubowitz, illustrator Bill Hogarth, Courant Institute mathematicians George Morikawa and Howard Levi, sculptor/children’s author-illustrator Harvey Weiss, and Broadway stage designer Ralph Alswang. If Ad Reinhardt was there, the photos do not record his presence. Having suffered a heart attack in January, he may not have been feeling well enough to attend.2

Michael Benedikt was also there, representing Art News. He thought the paintings had “a certain cool insouciance” but were also “intensely personal: Johnson spaces in a lively way, converts theorem-subjects to decorative motifs, alters colors…. The painting is a kind of cool Hard-Edge, but bouncy overall.” The Bridgeport Sunday Post liked “the fanciful, often lyrical geometric abstractions which flow from Johnson’s imagery.”3

Johnson seemed uncertain about his precise professional identity. Painter? Scholar of mathematics? Cartoonist? The exhibition program points to all three. Abstractions of Abstractions is a witty title for a show, but its subtitle sounds like a doctoral dissertation. The back of the program features a quotation from the Museum of Modern Art’s director of collections, Alfred Barr, “It’s obvious today that comics are art. Just because these things are vulgar doesn’t mean they are not art.” In this context, the comment alludes to the fact that royalties from children’s books and Barnaby certainly were underwriting Johnson’s new artistic career.4

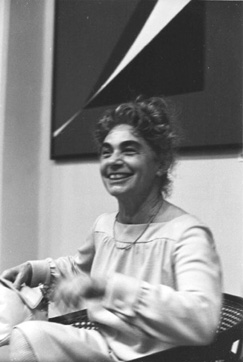

Ruth Krauss at the Glezer Gallery opening, 5 April 1967. Photo by Jackie Curtis. Used by permission of Jackie Curtis.

Indicative of his bemused attitude toward his new and uncertain status as painter/math student/cartoonist, when people asked what he did for a living, he would invent a job title for himself. In the late 1960s, Johnson bought a secondhand Mercedes-Benz touring car which often needed repairs. At a party, someone who did not know him would ask, “What do you do for a living?” Johnson’s reply: “I own a Mercedes-Benz.” That answer was easier than confessing his aspirations to be taken seriously as a painter.5

Crockett Johnson at Glezer Gallery opening, 5 April 1967. Photo by Jackie Curtis. Used by permission of Jackie Curtis.

Krauss knew what she was: a poet and playwright, albeit one who continued to write for children. By the spring of 1967, she had turned in the text and artwork for This Thumbprint and had finished What a Fine Day For …, a collaboration with Remy Charlip (design and pictures) and Al Carmines (music) that is a hybrid of her books for children and her poem plays for adults. Charlip’s loopy style and Carmines’s bouncy melody sustain Krauss’s sense of fun, as the book leads us through the day’s many possibilities. “What a fine day for …,” it begins, and we turn the page to greet “a mouse and a cat / a ball and a bat.” The next page offers “a ball and a throw / a stop and a go.” Charlip gives a pair of feet to each letter and each noun, not only the mouse and cat but the ball, bat, glove, and arrows (for stop and go). These feet, queuing horizontally near the bottom of the page, reinforce the impression that they are performing on stage and that readers are the audience.6

Krauss had also created a dummy for a new book, I Write It, and was hoping to enlist Ezra Jack Keats as illustrator, but he declined. She wondered if Maurice Sendak could do it. He understood her work. He was then heading to England, where, during a BBC-TV interview, he suddenly felt ill and unable to speak. The interviewer ended the conversation and gave Sendak some whiskey. His editor, Judy Taylor of the Bodley Head, suspected something more serious and called an ambulance. A month before his thirty-ninth birthday, Sendak had suffered a heart attack. Thoughts of asking him to illustrate her book left Krauss’s mind as she worried about his health. After he returned to the United States, she came to visit him on Fire Island, where he was recuperating. Sendak was touched by her concern, but their reunion was a bit awkward: “She was restrained or constrained when she came here, as though she had to be an old friend and no longer a collaborator—it was an uneasy feeling.”7

Worried about Sendak’s recovery and feeling herself in need of a rest, Ruth and Dave took a mid-May trip to Montauk, at the eastern end of Long Island, where the weather began to impersonate England’s: cold, fog, rough seas. By mid-August, they were preparing for a return to England. To avoid another entropic homecoming, they asked Sid Landau and his new wife, Genevieve Millet, editor of Parents magazine, to spend weekends at 74 Rowayton Avenue, “patching the leaks, paying the taxes, running out on the dock & yelling at passing boats,” as Ruth put it.8

Dave and Ruth spent late August and early September on a ship crossing the North Atlantic and traveling up the west coast of Britain. After a long voyage complicated by constant rain and ill health, they reached Edinburgh, Scotland, on 19 September and spent a week there sightseeing and resting. On 25 September, they decided, as Ruth said, “to continue their journeys to the Shetland Islands, home of Big Davie’s Pa. Aye.” They boarded “a cattle boat” for a “rough & tough but great” trip to the Orkneys and Shetlands. When they arrived, Ruth was amazed that the Shetlanders “all looked like Dave” and that “everyone in the Shetlands has Dave’s last name (Leisk or Leask)…. Millions of relatives, in the woolie stores, the fishing boats, the busses, taxis, weavers, everyone.”9

Arriving in London on 5 October, Ruth and Dave visited Mischa Richter’s son, Dan, and his wife, Jill. Richter told them about his year working with Stanley Kubrick, choreographing and casting “The Dawn of Man” opening to 2001: A Space Odyssey, with Richter himself starring as Moonwatcher, the leader of the gorilla tribe who in the scene’s final moments tosses the bone into the air. Ruth and Dave were impressed. Richter also showed them his paintings and talked with Ruth about the his underground poetry magazine, Residu, which had published her “There’s a Little Ambiguity over There among the Bluebells” in 1964. From that day on, she called him “my publisher”—which he found both flattering and amusing. After nearly two weeks in London, Dave and Ruth left for what he called “a rush through Bruges and Brussels (if this is Tuesday this must be Belgium) to Paris.” On 2 November, they boarded the Queen Elizabeth at Cherbourg, France, and they were home ten days later, happy to have hard beds and American plumbing.10

But in late August, while they were gone, their old friend Ad Reinhardt had died after suffering his second heart attack in less than year. It is not clear whether Ruth and Dave learned of his death while in Europe or when they returned three months later, but the news hit them hard. Back in the States, Ruth sent her only copy of A Good Man and His Good Wife (her first book, illustrated by Reinhardt) to his widow, Rita, and their thirteen-year-old daughter, Anna.11

The fall of 1967 and spring of 1968 brought better news, with strong reviews of What a Fine Day For …. Kirkus thought that the book of “free-swinging nonsense” was not for “routine circulation” but was nonetheless “a very original device to arouse group participation, with music (and chord indications) for an experienced pianist. Teachers from nursery school up will want to have a try.” Library Journal, too, believed this “delightful bit of nonsense” had “great possibilities for use in both language arts and music.” With this book, Krauss, Charlip, and Carmines had proved that her work for theater could be adapted for children.12

After the Glezer Gallery exhibit, Johnson was no longer content only to paint the theorems of others. As J. B. Stroud puts it, Johnson “fell in love with the three infamous unsolved compass and straightedge problems of the classical Greeks: squaring the circle, the ‘Delian’ problem of duplicating the cube (begin with a unit cube, and then construct a cube with twice its volume), and the trisection of an (arbitrary) angle.” Johnson decided that he would solve these puzzles, starting with squaring the circle, a problem that also intrigued and annoyed Lewis Carroll.13

“Squaring the circle” means constructing a square with the same area as a circle but doing so with only a straightedge and a compass. It is impossible, but Johnson was either unaware of or undeterred by this fact. He recognized the problem as related to the squaring of a lune (a figure shaped like a crescent moon) and created a trilogy of paintings on the latter theme, each one more sophisticated than the last.14

Sixteen paintings related to circle squaring followed. One, Biblical Squared Circles, was inspired by a Bible verse, 1 Kings 7:23: “Then he made the molten sea; it was round, ten cubits from brim to brim, and five cubits high, and a line of thirty cubits measured its circumference.” The resulting artwork is more a reflection of Johnson’s fascination in finding this biblical resonance and less a step in the actual problem solving. Johnson was using this phase of his life to read about many subjects that interested him, and one such topic was religion. Having enjoyed Robert Graves’s I, Claudius (1934) and The Greek Myths (1955), he turned to Graves’s King Jesus (1946) and The Nazarene Gospel Restored (1953) and to the Bible itself. Though his friends admired his wide range of knowledge and the seriousness with which he pursued it, they nonetheless were somewhat puzzled by the idea that a former communist was now studying up on Christianity. At the Rowayton post office, Johnson ran into journalist Andy Rooney, who asked, “Where you been?” Johnson answered, “Well, I’ve been reading the Bible.” When Rooney replied, “Oh, I’ve never known anybody who really read the Bible. How is it?,” Dave responded, “Well, there’s a lot of good stuff in it.” After a pause, he added, “But it’s a mess overall.” He joked about his reading but continued his research, concluding that Christ probably did not exist but instead was a composite of many different people. Though skeptical of the Bible as history, he found value in its spiritual and philosophical perspective.15

Crockett Johnson and a version of his Squared Circle, ca. 1972. Photo by Jackie Curtis. Used by permission of Jackie Curtis.

Krauss’s poems continued to keep extremely hip company. Intransit: The Andy Warhol Gerard Malanga Monster Issue (1968) published four of her poems as well as work by Lou Reed, John Cale, Nico, Andy Warhol, John Ashbery, the late Frank O’Hara, Allen Ginsberg, Phil Ochs, Charles Henri Ford, John Hollander, James Merrill, May Swenson, and Charles Bukowski. That group includes two members of the Velvet Underground (plus Nico, who appears on the band’s first album), the most prominent pop artist of the time (who designed that record’s iconic “banana” cover), two New York School poets, the leading Beat poet, a leftist folksinger, a surrealist, and five other important poets, one of whom is Krauss. By the end of the year, Something Else Press had published Krauss’s first book expressly for adults, There’s a Little Ambiguity over There among the Bluebells, a collection of her poems and poem plays. Remy Charlip, Dick Higgins, and George Brecht contributed ideas for staging the title poem’s first speech, “What a poet wants is a lake in the middle / of his sentence / (a lake appears).” The caliber of her collaborators indicates the regard in which she was held, and the book’s few reviews were positive. Library Journal described Krauss’s “delicate grammatical structuring” as “transform[ing] even our expectations of poetic reality.” The Nation praised Krauss as “part carefree surrealist, part sober vaudevillienne, part city pantheist.” Far from being “cutesy, kidsy and sudsy,” “a Harpo-like insolence informs most of these pieces and sometimes turns downright diabolical.”16

Krauss’s poetic insights develop from her careful listening, experimentation, and unexpected juxtapositions. In his mathematical work, Johnson’s insights were largely visual. As he admitted, he was “a desultory and very late scholar” of mathematics. He avoided algebra, he said, “because algebra, or my ineptness with it, tends to make me lose a graphic grasp of a picture.” Instead, he explained, “I played with what I knew in advance to be the elements of the problem, imagining them as a construction in motion, an animated film sequence with an infinite number of frames running back and forth between plus and minus limits across the point of solution.” Johnson worked out solutions by painting pictures of problems, testing different theories on his canvas.17

In 1968, he found a visual solution for the “squared circle” puzzle and wrote an algebraic explanation to accompany it. With the aim of publishing his discovery, he wrote to mathematicians and the scientifically minded, asking for opinions. He began corresponding with Alex Gluckman, an old friend and mathematician who worked for the Atomic Energy Commission in Washington, D.C.; Martin Gardner, author of Scientific American’s “Mathematical Games” column (and of The Annotated Alice); and Harley Flanders, a math professor at Purdue University and editor of the American Mathematical Monthly. They offered advice, suggesting books and articles he might read. At Gardner’s suggestion, Johnson also submitted his squared circle proof to the editor of the Mathematical Gazette, Dr. H. Martyn Cundy. In late May 1968, Cundy replied that Johnson had submitted what was “certainly a very close approximation to √π—one of the best I have seen. It is also delightfully simple, and I think we can spare a little space for it.” Only a year after deciding that he would not only paint theorems but create them, Johnson was going to become a published scholar of mathematics. His article, “A Geometrical Look at √π,” would appear in the journal’s January 1970 issue.18

In 1968, Johnson sent a print of Squared Circle to the Museum of Modern Art, though officials there declined to display his work. Other institutions were more interested, however, and for the first six months of 1970, his paintings were on display at the Museum of Art, Science, and Industry in Bridgeport, Connecticut. Yet he did not call himself an artist; he said he “made diagrams.” He continued to work on Masonite rather than on canvas. And instead of mixing the paint himself, Johnson would purchase wall paint in one of the colors available at Brandman’s Paints, a local hardware store.19

Gene Searchinger asked Johnson, “Are you going to sell these paintings? You know, they must be worth a lot of money. I mean, look at that one, that must be $10,000.” Johnson responded with a scornful look, saying, “$10,000— No!” He thought his paintings were worth a lot more. Johnson explained, “If I sold one, it would give the others value. And if the others had value, then on my death, I would impoverish my heirs.” In one sense, he was making a joke: He had no children to pay tax on any inheritance. In another sense, he was using humor to mask his doubts about being an Artist.20

While he expressed indifference to selling the paintings, Johnson did consider selling color lithographs of his work. He liked a plan suggested by Los Angeles arts consultant Calvin J. Goodman: Limited-edition high-quality reproductions, sold at between $250 and $350 each, could yield Dave more than $10,000. In 1971, Goodman lined up investors and put his own money into making a few sample lithographs. The financial backers pulled out, however, and the project collapsed.21

Johnson and Krauss continued to earn a living through the royalties on the children’s books they had published and through the foreign rights for their works. By 1970, his stories were being published in England, Germany, Holland, Italy, and Sweden, while hers were available in Czechoslovakia, Denmark, England, Finland, Holland, and Switzerland. Their income was substantial enough that 1969 saw them take two trips abroad—a February vacation to South America, and another summer cruise to Europe that included stops in Galway and Cobh, Ireland; Rotterdam, Holland; Oslo, Norway; and finally Scotland.22

In between the two foreign jaunts, Krauss’s back problems recurred, keeping her in bed for nearly a month. As she recovered, she was finishing the illustrations for The Running Jumping Shouting ABC and “thoroughly enjoying the drawing.” Her first poetry chapbook, If Only, also appeared during this time, and her work was gaining a wider audience through its inclusion in Ann Waldman’s The World Anthology: Poems from the St. Mark’s Poetry Project. It featured an excerpt from her Re-Examination of Freedom along with poems by Ted Berrigan, Joe Brainard, Jim Carroll, Andrei Codrescu, Allen Ginsberg, Gerard Malanga, and collaborations between Frank O’Hara and Bill Berkson and between John Ashbery and James Schuyler.23

After Krauss and Johnson returned from Europe, Ashbery came to visit them in Rowayton. Though familiar with each other’s work, they had never met. When she told Ashbery that If Only had drawn some inspiration from his work, he suggested “Faust” from his The Tennis Court Oath (1962), which begins: “If only the phantom would stop reappearing!” He offered to send her the poem if she lacked a copy.24

On 12 December, If Only …: A Ruth Kraus Gala! had its sole performance at the Town Hall in nearby Westport, Connecticut. Sponsored by the recently incorporated Weston-Westport Arts Council, the gala presented “theater poems,” “stories,” “ambiguities,” and “scenes,” according to the flyer, which was designed and illustrated by Krauss. The central image, a smiling girl wearing boots and a loose dress and carrying a star above her head, is a “self-portrait by Ruth Krauss: the artist as a young nut.”25

Suggesting her affinity for this image, she used it as the title page illustration her 1970 poetry chapbook, Under Twenty, which also included her self-portraits as a flower and as a young star. Making its first appearance in a Ruth Krauss book was a poem that she wrote and O’Hara arranged. One of seven pieces titled “Poem,” it contains the word lost twenty-one times. Playing on the word’s sense of absence (“lost lost / where are you”) and presence (“lost / in my eyes”), this “Poem” conveys an ambivalent mixture of both lack and longing. The only work in the collection that had not previously appeared in print, “Tabu,” offered a lyrical exploration of what we “never name” but can “write what it looks like feels like seems / like resembles.”

Ruth Krauss, “Self-Portrait by Ruth Krauss: The Artist as a Young Nut,” 1969. Image courtesy of the Northeast Children’s Literature Collection, Dodd Research Center, University of Connecticut, Storrs. Reprinted with the permission of the Estate of Ruth Krauss, Stewart I. Edelstein, Executor. All Rights Reserved.

In early 1970, concerned that There’s a Little Ambiguity over There among the Bluebells was not selling, Krauss wrote to Dick Higgins, Something Else Press’s founder and publisher. Echoing Ferlinghetti’s assessment five years earlier, Higgins explained that Krauss’s fame as a children’s author presented booksellers with a problem of taxonomy: “You’re too well known—but for something else. Stores put the book in the juveniles section and wonder why it doesn’t go from there. Or if they put it in the poetry section, the poetry buffs don’t know well enough who Ruth Krauss is, so they never pull it down to give it a whirl. And they never put it in the drama section, because the plays don’t look like plays and it just doesn’t occur to the clerks to do so.” To get the work to sell, Krauss needed to become more identified with her poetry and plays than with her children’s books. While the Judson’s presentation of A Beautiful Day had been fantastic, it was also “about four or five years ago,” and “there have only been a few isolated things since.” She needed “a big Off-Broadway GRAND! RETROSPECTIVE!! EVENING!!! OF!!!! RUTH!!!!! KRAUSS!!!!!! Complete with all the frills and trimmings. (Well, On-Broadway would be okay too, but harder to arrange.) Not a one night stand, but a regular production. Probably in repertoire by La Mama, but better, simply a straight commercial production. Ideally, directed by Remy. If you want my advice—and maybe you don’t though I hope you do—I really think you should concentrate as much of your energies as possible toward this goal. If you do that, then I think the book will take off.”26 But Krauss was pursuing art for its own sake and was not interested in marketing her new identity as avant-garde poet.

Johnson and Krauss remained concerned about the Vietnam War and were regulars at Westport’s World Affairs Center, a bookstore and organization that advocated peace and human rights. She participated regularly in the center’s peace vigil, held each Saturday morning in front of Westport’s Town Hall. Johnson also opposed the war but voiced his opposition through petitions and the ballot box, giving him more time to work on mathematics and painting. Having settled the matter of the squared circle, Johnson moved on to tackle duplicating the cube, the second ancient mathematical problem that had fascinated him. He created six paintings on this theme, including two based on Isaac Newton’s construction and two based on his own original solution.27

In April 1970, Ruth and Dave took off for a brief holiday, returning to Montauk, at the eastern tip of Long Island, where they had vacationed three years earlier. Ruth thought that either Montauk or the Berkshires would be a great place to have a summer house. Dave was tiring of painting in their Rowayton basement, and both he and Ruth disliked the increased noise that summer brought to their Connecticut home, where “the vicious cutout car and choked-up motorbike noise is so bad we have to flee.” For the summer of 1970, they fled to Stockbridge, Massachusetts, where they rented a wing of Erik Erikson’s house on Main Street. Ruth had her leg in a cast after dropping an iron on her bare foot, and the injury was driving her “nuts”: “Never again! No more ironing,” she vowed. But the cast was coming off soon, and she was trying to write a show that Boston University’s drama department had asked her to develop for the spring of 1971. She was also sending book ideas to Harper, including a small poetry collection and a picture book based on a poem. Ursula Nordstrom was increasingly focused on her administrative duties, and Krauss was working more closely with editor Barbara Borack, who encouraged her to send in the poems. Johnson painted and corresponded with mathematicians from his Stockbridge studio but spent most of his time painting, at least until late August, when he “jumped into a lake off an unsmooth rock” and “shattered the most expensive and slowest-healing bone in the body, fifth metatarsal,” landing in the hospital for a week. Ruth enjoyed the “culture-minded” community and was delighted by the many “cultural goings-on”—“theatre, symphony, dance festival, Boston University’s drama school, etc.” Both she and Dave wondered whether Stockbridge might be a better place for them to live.28

After they returned to Rowayton in mid-September, Krauss sent more poetry to Harper in hopes of interesting her editors in a new book. She had reason to be optimistic. Her latest children’s book, I Write It, had received many notices, nearly all of them laudatory. The Saturday Review thought that the “poetic text bubbles along” and liked Mary Chalmers’s “endearing small figures,” which “romp[ed] through the pages of a book that celebrates the joy of being able to write.” The Christian Science Monitor praised it as an “unpunctuated little enchantment … illustrated in truth and childhood.” The reviews were a relief for Krauss. For nearly thirty years, she had wanted to address racism in her children’s books. Where I Want to Paint My Bathroom Blue argued for integration only through metaphor, I Write It did so directly. She had initially worried that its illustrations of a multiracial group of children were not sufficiently sensitive to race. In light of the 1968 assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy, she had a strong “desire, at this point in our country’s ‘race’ & ethnic problems, not to offend anyone.” It would be her last book for Harper.29

As 1970 drew to a close, Ruth and Dave’s injuries had made them painfully aware that life is short and that health can be tenuous. Three and a half months after Dave’s accident, he was only just beginning to walk normally again. In July, she would turn seventy, while he would be sixty-five in October. It was time for a few changes.30