—and when we pass a cemetery, we both

hold our breath alike, like twins,

even when we’re not together.

—RUTH KRAUSS, I’ll Be You and You Be Me (1954)

In the fall of 1989, Dave’s studio was empty again. When Nina Stagakis visited, Ruth asked whether she and her family could move in, living there rent-free in exchange for serving as her caretakers. Stagakis realized that having the five members of her family living in a single room would be impractical. So Ruth placed another ad in the paper.1

The ad was answered by Joanna Czaderna, a Polish immigrant who was seven months pregnant at the time. Although she was employed, she was having difficulty finding a place to live because landlords refused to rent to a pregnant woman. But when she knocked on the door of 24 Owenoke, Ruth opened it and said, “Oh, welcome! So, where is your stuff?” Czaderna and her husband, Janusz, became a part of the household, followed by their daughter, Bianca, who arrived in December 1989. Needing to care for her newborn as well as her mentally unstable husband, Czaderna was unable to work, and she began to worry about how she would afford the rent. Though she did not raise the matter, Ruth understood and offered to let the Czadernas stay for free if Joanna would help around the house. The younger woman gratefully agreed.2

Ruth’s other friends wondered how she would adapt to having an infant in the household, but much to their surprise, she enjoyed Bianca’s company. A very easygoing baby, Bianca would play quietly next to her mother and Ruth, and when the girl got older, she would crawl over and sit in the eighty-nine-year-old author’s lap, where Ruth would hug her “little angel.” Ruth would also read her books to Bianca, the grandchild she never had.3

Joanna Czaderna became Ruth’s confidant and chauffeur. Traveling in Ruth’s little Honda, they began to visit the places Ruth had lived and worked— the Rowayton house, the schools where had interviewed children. She finally became able to talk about Dave without being overcome by grief. Her face lighting up, Ruth described Dave as a gentleman who treated her like a princess. Czaderna was surprised: “I just never heard anyone speaking with such a love about another person, and especially coming from her, it was even more powerful to me.”4

Returning to one of her favorite childhood activities, Ruth began making books for her own amusement—writing the story, drawing the pictures, and sewing the pages together with yarn. In one of these stories, a variation on “Love Song for Elephants” from I’ll Be You and You Be Me, she wrote of a stuffed elephant who grows old, gets worn out, and is thrown in the garbage. A little girl finds the sad elephant, takes him home, and repairs him.5

In July 1992, Ruth’s good health suddenly deserted her, and she took to her bed, requiring round-the-clock care. Nurses came in for a few hours each day, but Czaderna became her primary caregiver. Helplessness devastated Ruth, and she fought to lift herself out of bed, though she lacked the strength. Her body was failing, but her will remained strong.6

Friends and fans came to visit. Barbara Lans, Lillian Hoban, Morton Schindel, and Maureen O’Hara came regularly. Maurice Sendak visited several times, and Shel Silverstein visited once. Ruth began giving things away. When Dan Richter stopped by, she gave him some of Dave’s books—Boswell’s Life of Johnson and a book on seventeenth-century thought.7

Another regular visitor, Janet Krauss, was struck by Ruth’s humor and defiance. When Janet mentioned that she was going to attend a poetry festival, Ruth asked, “A poverty festival?” “No, a poetry festival,” Janet replied. “Oh, those things,” Ruth laughed, enjoying the misheard phrase. After sitting at Ruth’s bedside and noticing her fist, Janet composed a poem comparing Ruth to “an aged Barbie doll / with flowing white hair,” and asks, “Why do you never let go / let your hand fly open? / A fist of anger / or defiance / against your still life.” Bianca and Joanna Czaderna also sat with Ruth, but she was hard to comfort. She was frustrated, imprisoned by a body she could no longer control. She ultimately stopped fighting and simply lay in bed, waiting for the end.8

Aware that Ruth might not last much longer, Maureen O’Hara phoned Sendak to suggest that he come back for a final visit. Ruth was annoyed that O’Hara had made the call, and when Sendak arrived, she ignored him. He tried making conversation but got no response, and he was not sure if Ruth even recognized him. As he prepared to go, he leaned over and asked, “Could I kiss you goodbye?”

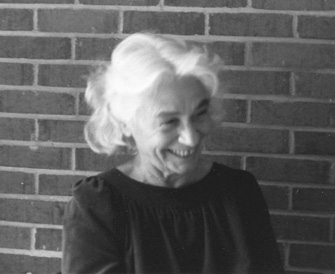

Ruth Krauss, late 1980s. Courtesy of Betty Hahn.

She did not object. He gently took her chin in his hand and kissed her on the lips. She giggled, and said, “Oh, Maury.” Sendak recalled, “I can’t tell you how much that meant. That she knew it was me all the time and that I had done just what she would have liked me to have done—to not have treated her like a dying person, but to have treated her like the beautiful woman that she was.”9

On 9 July 1993, Czaderna could see that Ruth was fading. Czaderna sat up with her friend all night and into the next day, stepping outside into the sunshine for a walk with her daughter only after one of the nurses arrived to tend to Ruth. When Joanna and Bianca returned, the nurse told them that Ruth had died. Three-and-a-half-year-old Bianca refused to leave Ruth’s side until the coroner came to take away her body.10

Ruth died on 10 July, one day before the eighteenth anniversary of Dave’s death and two weeks shy of what would have been her ninety-second birthday. The New York Times ran a short, error-laden obituary, suggesting that her life, though noteworthy, did not merit some basic fact-checking. The paper did, however, get her age correct.11

When Valerie Harms had asked fifteen years earlier whether Ruth ever thought of her creations as having an immortality of their own, Ruth responded, “How long can anything last? Especially in this time of space travel and exploration of other parts of the universe, posterity means nothing.” Amending her statement slightly, Ruth added, “Everything of course has repercussions or, rather, intersects with everything.”12

Conscious of those repercussions, Ruth did not forget the people and ideals that were important to her. She had finally made a will in early 1991, after decades of avoiding the subject. She consulted her cousin, Dick Hahn, and his wife, Betty, and initially planned to leave her entire estate to him. When he said he did not want her money, she made other arrangements. Bianca Czaderna received fifty thousand dollars to help with her education. Crockett Johnson’s paintings went to the Mathematical Division of the Smithsonian Institution. Ruth Krauss left the remainder of her estate (which also included Johnson’s estate) to charitable “organizations which are dedicated to meeting the needs of homeless children in the United States,” stipulating only that the organizations “have no particular religious affiliation.” As she had written forty years earlier in A Hole Is to Dig, “Children are to love.”13

At the time of Ruth’s death, Sendak’s new book about homeless children, We’re All in the Dumps with Jack and Guy, was in production. When working on the book, Sendak found himself “going back to the A Hole Is to Dig kids.” He had been “unnerved” by reports of homeless children in “Venezuela, South America, children being killed on the street by police like rats and vermin.” Thoughts of these kids “brought [him] back to the happy little ragamuffins in the Krauss books.” We’re All in the Dumps was released in the fall, and the cover of the 27 September issue of the New Yorker featured a Sendak illustration of the book’s homeless children. Sleeping on the ground, a boy uses A Hole Is to Dig as a pillow. Standing beneath a makeshift shelter is a girl who has Ruth Krauss’s dark curly hair and who is holding a copy of I Can Fly. The girl’s eyes are closed, as if dreaming of flying.14

Sendak was unable to attend her memorial service but sent a loving reminiscence that Hoban read at the gathering and that formed the basis of his appreciation of Krauss published in the Horn Book the following year. Sendak said, “Ruth broke rules and invented new ones, and her respect for the natural ferocity of children bloomed into poetry that was utterly faithful to what was true in their lives.” Remy Charlip, who also could not attend the service, sent a piece in which he spoke of how Krauss inspired him. When he asked where she had come up with the wonderful title “The Song of the Melancholy Dress,” Krauss replied, “I misunderstood a woman at a party, who told me she just bought a melon-colored dress.” So, Charlip concluded, “Ruth taught me how to use my misunderstandings and my so-called failures and mistakes. And in the process I learned how to respect other people’s creative interpretations of what I say or do. For this path to artful enlightenment, I will be forever grateful to Ruth.”15

In accordance with Ruth’s wishes, she was cremated and her ashes scattered in Long Island Sound. At 5:00 A.M., on 21 June 1994, the day of the summer solstice, Ruth’s executor, attorney Stewart Edelstein, got into a canoe in Fairfield, Connecticut, and paddled out onto the sound. Dave had loved to sail there. For more than three decades, Ruth and Dave had lived together on the shore. And nineteen years earlier, his ashes had been scattered there. If Dave’s spirit were anywhere, it would be there.16

Out on the water, Edelstein recalled one of several visits to Ruth’s house, during which they ate cookies and worked on her will. Either he or Ruth had said something funny, and Ruth laughed—not a polite laugh, but a deep belly laugh. He thought of that moment, and “it was like she was there with me.” As he scattered Ruth’s ashes into the water, the sun rose.17