Over the past few decades, the UK has seen an unprecedented boom in housing prices, but one that has been very unevenly distributed, with London and the south-east the chief beneficiaries. Concerns abound that house prices are reinforcing geographical inequalities in Britain by making internal migration difficult, thus locking in advantage and disadvantage across regions. The British housing market also makes inequality worse because for many it acts as a substitute for the welfare state, with individuals relying on their housing wealth to help provide for retirement and insure against labour market shocks.

So, housing is important in economic terms. But it also matters politically, for two main reasons. First, since people can choose where to live – within reason – they often sort into like-minded areas. And this tendency can be reinforced by a second effect: the tendency of the local environment to influence how people perceive the world. If you feel that people in your local community are never listened to, it’s not surprising you might be suspicious of national and supranational authority – both of Westminster and of Brussels. If people in your area are struggling with unemployment and stagnant wages, you may feel the economic status quo is not working, whatever is happening in other, perhaps booming, regions. And if people around you all express similar opinions about political matters – say, the merits of Brexit – that is likely to reinforce your convictions.

Owning a house amplifies these effects. Houses are geographically fixed – save for owners of mobile homes, you cannot move your house with you across the country – and the housing market is quite illiquid – it is costly and laborious to move house, so people do it rarely. Plus, house prices vary dramatically across the country, so you might not be able to afford to move. Houses lock people into their local communities, for good and for ill. And that means that how a local community is faring will have particularly strong effects on homeowners, who are literally and figuratively invested in such communities.

Given all of this, it should come as no surprise to discover that there was a relationship between that perennial British obsession – house prices – and the Brexit vote. While people voted to Remain or Leave the European Union for a range of reasons, one important factor was how they felt their communities had fared over the past few decades of EU membership. Those communities that were falling behind economically appear to have been those, on the whole, where support for Leave was strongest. And house prices give us a sense of this effect – one way of thinking of house prices is as the price people are willing to pay to join a community. House prices are thus a great indicator of exactly how much people value various locations as places to live. Such prices turn out to be stronger predictors of support for or opposition to Brexit than other local economic indicators such as unemployment and average wages.

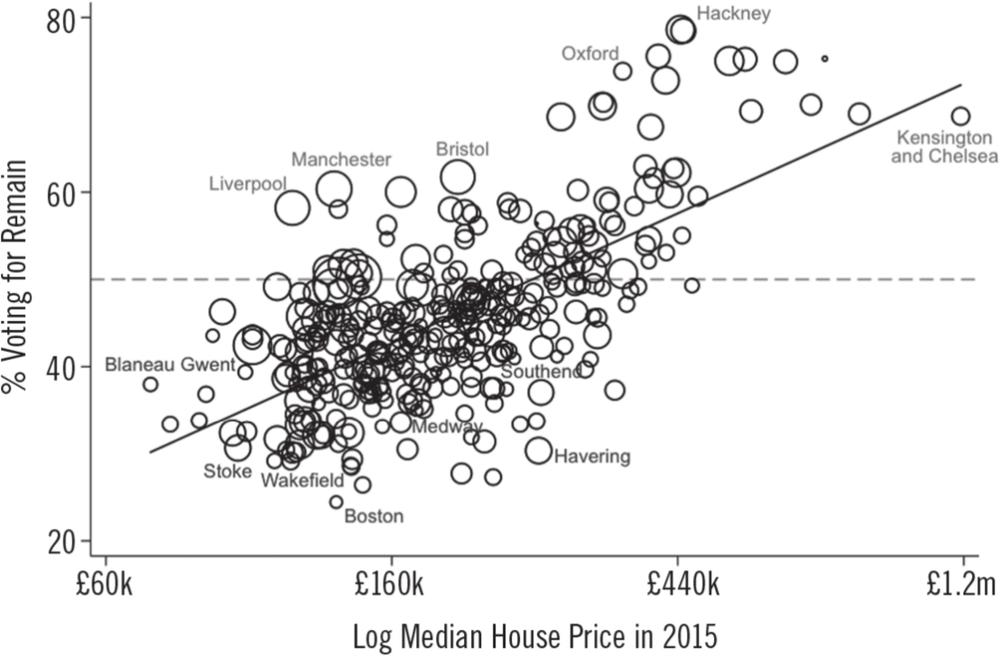

The graph demonstrates the relationship between support for Remain and average house prices in each local authority in England and Wales. The size of the bubbles in the figure reflects the population of each local authority.

HOUSE PRICES AND SUPPORT FOR REMAIN AT THE LOCAL AUTHORITY LEVEL IN ENGLAND AND WALES

Note: This figure shows the relationship between house prices and the percentage of the EU referendum vote for Remain. The size of the bubbles reflects the population of the electorate. House prices are logged in order to compress areas with very high prices.

There was a very strong positive relationship between house prices in a local authority and support for Remain. Areas with median house prices of around £100,000 in 2015 averaged a 30 per cent Remain to 70 per cent Leave split, whereas those with median prices above £500,000 averaged the reverse: 70 per cent Remain to 30 per cent Leave.

Some indicative local authorities have been labelled on the figure. House prices alone explain around half of the variation across local authorities in the Brexit vote. But whereas most fit pretty closely to the line, we do see some outliers – Liverpool, Manchester, Bristol and Oxford were all more pro-Remain than predicted by house prices and Boston, Medway and Havering more pro-Leave. So prices alone do not explain everything. Still, the overall pattern is strong, and, importantly, it remains if we add statistical controls for unemployment, income, ethnic composition and age profile. And the pattern holds up within local authorities (if we compare wards where we have data) and is strongest among homeowners: the people who are the most locked into how their community is faring.

House prices map on to Brexit voting much more strongly than they do on to traditional Labour/Conservative voting, highlighting how the divide exposed by Brexit creates problems for both parties. It’s not surprising that both parties are torn, with many Labour MPs in areas with cheaper housing worried about keeping hold of Leave voters, and Tory MPs in leafy south-eastern suburbs concerned about angry Remainers. It also highlights one of the consequences of the 2010–15 coalition’s choice to engage in fiscal austerity, relying on the Bank of England to engage in unprecedented monetary stimulus. This led to a second housing boom as the south-east shot away from the rest of the country again, even as wages flatlined and public spending collapsed elsewhere. Wealthy, traditionally Conservative areas saw large increases in house prices, which in turn underpinned support for Remain. In the meantime, poorer, traditionally Labour areas had stagnant housing markets, reinforcing community support for leaving the European Union. This further polarised Britain’s economic geography, mirrored by its unequal housing market, and set the scene for a new and chaotic form of polarisation from 2016 onwards.

FURTHER READING

The links between house prices and voting are analysed in ‘Housing and Populism’ (West European Politics, 2019) by David Adler and Ben Ansell and ‘The Politics of Housing’ (Annual Review of Political Science, 2019) by Ben Ansell. For a broader analysis of the geographic polarisation discussed here see ‘The divergent dynamics of cities and towns: Geographical polarisation after Brexit’ by Will Jennings and Gerry Stoker (Political Quarterly, 2019). A good general overview of the politics of housing in the UK is All That Is Solid: The Great Housing Disaster by Danny Dorling (Penguin, 2015).