Sami People

The total population of Lapland is around 900,000. Sami population is about 10% of the total number of people living in Lapland. Estimations for the number of Sami people vary because it is not a plain and simple thing who is counted as a Sami (it is even argued in the Sami Parliament from time to time). In any case, it is estimated that:

50,000-65,000 Sami live in Norway.

20,000-40,000 live in Sweden.

8000 in Finland.

2000 in Russia.

A Sami man in traditional costume at his reindeer farm near Rovaniemi. Photo copyright Visit Rovaniemi / Rovaniemi Tourist & Marketing Ltd.

Sami Homeland is defined as the region north of Central Norway and Central Sweden through the northernmost part of Finland into the Kola Peninsula. In Finland, the Sami Homeland has legal status. It covers the municipalities of Enontekiö, Inari and Utsjoki, as well as the reindeer-herding district in Sodankylä. Sami people in Finland are entitled to public services in Sami language in their Homeland.

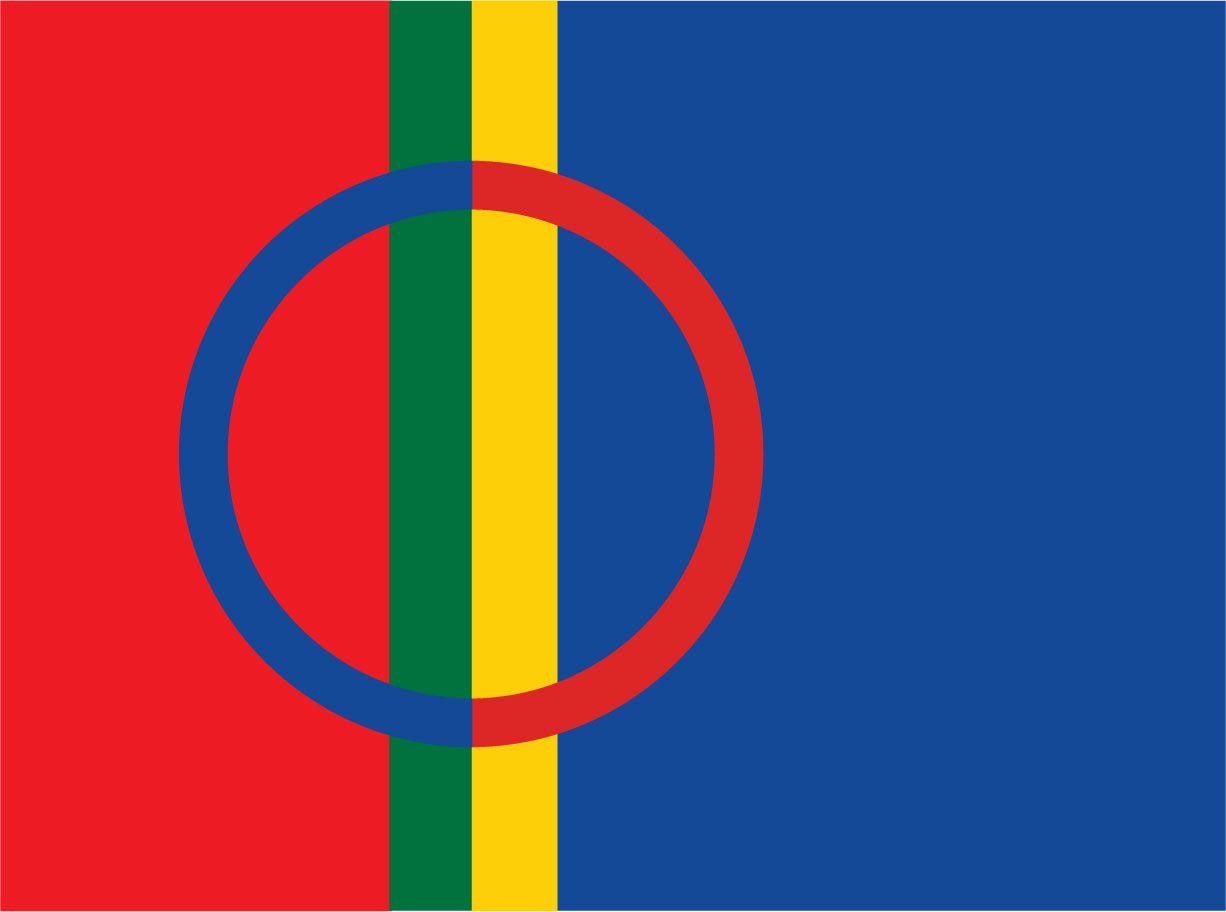

The Sami flag (source: norden.org).

Every traveler who tours Lapland will spot a colorful flag in many places, for instance, in front of shops, houses, and museums. It is the Sami flag that was approved as an official flag in 1992. The red section in the circle symbolizes the sun, the blue section the moon. All colors reflect the colors of traditional Sami costumes. Green represents nature, blue water, red fire and yellow is the sun.

Sami culture

The Sami are not a single cultural entity, but is comprised of groups that have been defined by their own languages and traditional means of livelihood. Earlier the Sami were categorized into five groups that reflected where they lived and what they did: Forest, Reindeer, Sea, Lake and River Sami. Hunting, herding or fishing were the primary means of livelihood.

Today's Sami people as photographed by Antonio Briceno. The image was captured at Siida Museum's "520 poroa" exhibit (Inari, Finland).

Many Sami groups used to live a nomadic life, moving between summer and winter sites. They have little written history because they used to transfer history orally to the next generation. The first written Sami texts are from the 17th century, but only in the 20th century was a unified spelling system develop2ed for all the Sami languages and dialects.

The most frequently visible elements of the Sami culture for a traveler are traditional handicrafts, like wooden cups, knives and other household items made of reindeer bones or wood. Also traditional costumes, hats, gloves and boots are marketed at shops across Lapland.

Traditional Sami drums and joik chanting are originally related to shamanism. Chanting was also a way to tell stories by singing it as a joik.

If you are driving in Lapland, tune your FM radio to a Sami channel. Each Scandinavian country has its own nationwide public radio and television network. In Lapland, each state's public radio organization has a dedicated channel for the Sami culture. In Finland, the Sami radio is called Yle Sami (yle.fi/uutiset/sapmi). In Norway, NRK Sami Radio broadcasts music and news (radio.nrk.no/direkte/sapmi). In Sweden, radio channel SR Sapmi is dedicated to the Sami culture (sverigesradio.se/sameradion).

If you have an opportunity to watch television in Lapland, daily Sami news are broadcast on Finnish Yle channels, Norwegian NRK channels and Swedish SVT channels. Sami news are titled Oddasat.

Sami languages

Sami people are not one uniform group of people, but consists of many communities who may have their own Sami language or dialect. Traditions, administration of the communities and principal means of livelihood varies as well.

The Sami languages belong to the Europe's indigenous languages. Sami languages are categorized as Finno-Ugric languages related to Finnish, Estonian and Hungarian. Sami is spoken in northern Finland, Sweden and Norway and in northwest Russia.

Each country in Lapland defines the number of Sami languages and dialects its own way, but the overall picture is that there are three major Sami languages: East, Central and South.

East Sami language is spoken in Kola peninsula in Russia and in the easternmost region of north Finland. Central Sami and its dialects are common in all countries of Lapland. South Sami is spoken in Norway.

In Finland, North Sami, Inari Sami and Skolt Sami are official languages recognizes by the state. For example, the town of Inari has four official languages: Finnish and three Sami languages.

North Sami is the most widely spoken of these languages with approximately 20,000 speakers in the whole Scandinavian Lapland. Skolt Sami is spoken in Finland and in Russia.

History

The first concrete signs of permanent settlements in Lapland date back 7000 years when ice that had covered Scandinavia slowly retreated. Rock carvings in Alta, Norway are estimated to be up to 6000 years old. Many of those paintings depict animals and hunting. In Rovaniemi, Finland, a wooden sculpture of an elk head has been dated to 5800 B.C. Other ancient objects discovered indicate that people who lived there at that time traded with their eastern neighbors in today’s Russia and western neighbors in Sweden and Norway.

Sami people used to live in a large area in central and north Finland, including Karelia on both sides of the current Finnish-Russian border. They lived on hunting and fishing. Farming culture gradually expanded from south towards Lapland, bringing new groups of people to the region, and pushing Sami further north. By the 9th century, peasants had settled fertile riverside estates all the way up to Tornio.

During the Middle Ages, furs and skins were the primary exports from Lapland. Sweden's king sent Christian missionaries to Lapland in the 17th century to convert people from their ancient naturalistic beliefs and shaman culture to Christianity, and to make them obedient to the crown.

Sami people lived and roamed in the far north as they wished and weren't really part of any state. Scandinavian state borders were not explicitly specified in Lapland and at times, Sami were required to pay taxes to multiple states.

The central concept of a Sami community is Siida, a region with borders. Siida's centerpiece was a particular natural object that was the home of a worshipped god (Seida). One of the most famous places is the rocky island Ukonsaari in the lake of Inari (Inarinjärvi). Sacrifices were given to gods in these places. A Shaman had a magic drum to connect with the god. He chanted (joik) along with the drum beat.

Sami people who herded reindeer or fished for living were nomads. They moved with the seasons, for instance further north in summer, and returned to southern regions of Lapland in winter.

In the 17th century, farmers claimed even more land in Lapland, moving into the same territory where Sami people lived. Farmers cleared land by burning patches of forests, and they hunted as well. Sami people were forced to move further north. Competition from land and food forced Sami increasingly to adopt reindeer herding as their livelihood. The latest DNA studies indicate that reindeer is a species of its own – not bred from deer.

Large untouched forests were a resource that emerging industrial enterprises in Nordic countries wanted to make use of. In the 19th century, additional labor was imported from south to work in forest industry. The first roads were built to Finnish Lapland in the end of 19th century. For instance, Kittilä, Kolari, and Sodankylä were joined to the national road network then.

Finnish and Norwegian Lapland suffered significant losses in the World War II. Germany invaded Norway in April, 1940 in order to gain control of Norway's Atlantic coast. One of the famous battles between Norwegian and German troops took place in Narvik, an important port for mining products. In 1944,as German troops were forced to retreat south, they destroyed what they could. For example, 70-90% of buildings in Finnish Lapland were destroyed in the period from September 1944 to April 1945. Many coastal towns in northern Norway were completely demolished. In towns like Alta or Hammerfest there are practically no old buildings.

Tourism is an important, growing source of income for Lapland. Mining companies are also constantly looking for opportunities to open new mines (which the Sami and environmentalists promptly oppose).

Today

Growing tourism industry has introduced new opportunities to Sami people for livelihood. Large ski resorts and other vacation destinations that have been built especially in Finnish Lapland bring work and allow entrepreneurs establish new businesses.

Young Sami at a cultural festival in Inari. Photo by Siida Sami Museum.

Reindeer husbandry is still considered the traditional Sami way of living. The number and ownership of reindeer is regulated, making it a static profession. The organization of reindeer owners decides if new herders are allowed to purchase animals. The objective is to only have as many animals as the land can naturally support.

In the old days, skis, dogs and reindeer were the means of transportation in Lapland, but today, snow mobiles, all terrain vehicles and motorcycles have replaced them. GPS satellites and mobile phone technology help herders locate their reindeer.

Norwegian Sami were the first to get their own parliament in 1989. It was established in Karasjok. Sweden granted Sami people the right to elect Sami parliament members in 1993 (the parliament building is planned for Kiruna), and Finland's Sami got their own parliament in 1996 (based in Inari). The mandate of the parliament differs slightly in each country, but the common thing is that they are financed by the states. The common mandate for the parliaments is to develop Sami culture, maintain traditions and language, and to be the voice of Sami people towards national parliaments in matters that concern Lapland.