CAMERON HOUSE AND WAVERLY PLACE, 2017 AND 2018

We met Dorothy G.C. Quock, better known as Polka Dot, at an opening party for Eat Chinatown, a photo exhibit we produced that chronicled longtime restaurants in the neighborhood. She brought in an old matchbook from a long-gone restaurant to contribute to our wall of vintage restaurant menus and ephemera.

Living up to her name, she wore a pink raincoat studded with white polka dots. She got her nickname at Donaldina Cameron House, a Presbyterian family and youth organization in Chinatown. There was another person named Dorothy, so the executive director nicknamed her Polka Dot, and it stuck. At the time, she didn’t wear polka dots much, but now it’s her signature look.

We met her one day at the Cameron House rooftop basketball court, where Polka Dot demonstrated her tai chi moves, which she practices daily. She wore an all-red outfit with a polka dot turtleneck underneath a ruffled shirt. Her accessories included a hair clip with Guatemalan worry dolls (a gift from her daughter) and cotton Mary Janes, to the tips of which she had affixed pom poms to patch up a hole.

“I grew up here,” she said of Cameron House. Polka Dot was in the first group of teens to join the youth program in 1947, when she was thirteen years old. She spent most of her youth at Cameron House until she moved away for college, so much so that her mother quipped, “Why don’t you move your bed there?”

On Friday nights they held socials, where teens would learn about “the birds and the bees.” Polka Dot also learned about civic responsibility and politics through the youth program. Although she’s no longer active in the religious aspect of Cameron House, it taught her the importance of social change and community work.

Polka Dot has shown us what it means to be community- minded. One afternoon we were at her apartment in Chinatown, which she moved back to in 2003 after spending forty-one years in Livermore. “It was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to get this apartment,” she said.

Her front door, which is mostly made of frosted glass, was covered in posters and stickers that advocated for universal health care, “Impeach Bush and Cheney” signs, and a flyer that said “Bring the Troops Home—Bay Area United Against War.”

Her political hero is Ralph Nader, who’s run for president four times. During his run in 2000, Polka Dot campaigned for him—referring to herself as a “self-appointed campaign manager of Nader in the Fremont-Newark area.” Since there wasn’t a campaign office in her town, she formed her own nucleus of Nader supporters—they registered voters and campaigned for him at BART stations and college campuses. One of her bucket list items is to take him on a walking tour of Chinatown.

Polka Dot thinks globally, but acts locally by taking care of her neighbors. On Mondays, she receives a delivery from the food pantry. She keeps a list of her neighbors and “what they can eat or what they like to eat” on her fridge—and distributes her bounty to them accordingly. Because our city is susceptible to earthquakes and fires,

Polka Dot has initiated an emergency response plan for her apartment building, which she created after receiving training through Neighborhood Emergency Response Team (NERT), a San Francisco Fire Department program. Although Polka Dot hasn’t experienced an emergency, there’ve been plenty of false alarms. “There’s old ladies that burn their rice every so often,” Polka Dot said with a laugh.

Recently, Polka Dot’s building was purchased by new landlords who increased her rent by three hundred dollars. As someone with limited income, she applied for a hardship waiver and also formed a group of residents, who dubbed themselves “The Gang of Five,” to appeal to the San Francisco Rent Board. She got her first rent increase waived, but no longer qualifies for a reduction. Community organizations like Chinatown Community Development Center (CCDC) and the Community Tenants Association helped advocate for Polka Dot at the rent board meeting. “I was so troubled after the hearing that I told CCDC ‘If you need a poster senior for tenants’ rights, let me know—I’ll consider it!’”

Nowadays, new tenants pay around three thousand dollars a month for a one-bedroom apartment, significantly more than what she paid when she moved there sixteen years ago. She said that there’s only “half of us” left in the building—people she refers to as “the old doors,” a reference to the people with the frosted glass doors, as opposed to the newer solid wood doors that replace the glass ones once an older tenant moves out. We asked where have they gone. “People have died; been evicted,” she said.

Polka Dot is a portal to what Chinatown is and was. On our first walk around the neighborhood with her, Polka Dot—wearing a five-piece cheetah-print outfit she had made herself—had a story to share every time we turned a corner. “See that building? I was a house girl for a well-to-do engineer. My sister had the job first, but when she moved away I took over. He had these outfits he’d want us to serve in—Chinese brocade blouses. I learned how to mix martinis for dinner parties,” she said, recalling one of her many Chinatown memories.

After working as a secretary for three institutions, she’s established her most recent career based on her longtime connection to Chinatown: She works as a guide for Wok Wiz Chinatown Walking Tours and also as a researcher for filmmaker James Q. Chan.

Polka Dot was born in 1934 in Chinatown, as one of eight kids. They lived in single-room occupancy housing (SROs) and houses all over Chinatown—at times with ten of them in one room. Before she graduated high school, they’d moved eleven times. “With so many of us, my mom probably got into arguments with neighbors,” she said.

Her father had arrived in San Francisco as a crew man on a freighter sometime between 1916 and 1918 and remained in the United States illegally. He delivered rice for work, dropping off fifty- and hundred-pound sacks to Chinatown businesses and residences. For a film premiere in 2016, Polka Dot took one of the heirloom cotton rice bags and turned it into a dress.

Her mother worked at the sweatshops that produced Levi’s, where she would bring Polka Dot and her siblings. Polka Dot described it as a crowded, dirty, and dimly lit place where the shades were always drawn so that people could not look in. As a preschooler, she got her first experience trimming thread ends. In second grade, she learned how to use an embosser to stamp the Levi’s logo onto the leather tag. At age ten, she mastered the buttonhole, five of which appeared on Levi’s before zippers became the norm. “We got two cents for every buttonhole we made, so it was very lucrative,” she said.

Child labor laws were not strongly enforced back then, so kids worked next to their mothers. There was always someone in front to keep watch for an inspector. “They’d yell ‘baahk gwái lai le’ [the white ghost is coming] whenever a white guy came in and we would run into the toilet and hide until someone told us it was safe to come out,” she said. (Baahk gwái is a Toisanese derogatory term for someone of European descent.) “It usually wasn’t a labor law inspector; it was usually a new Levi-Strauss driver that had come to pick up the finished jeans.” She says those were scary times for the children.

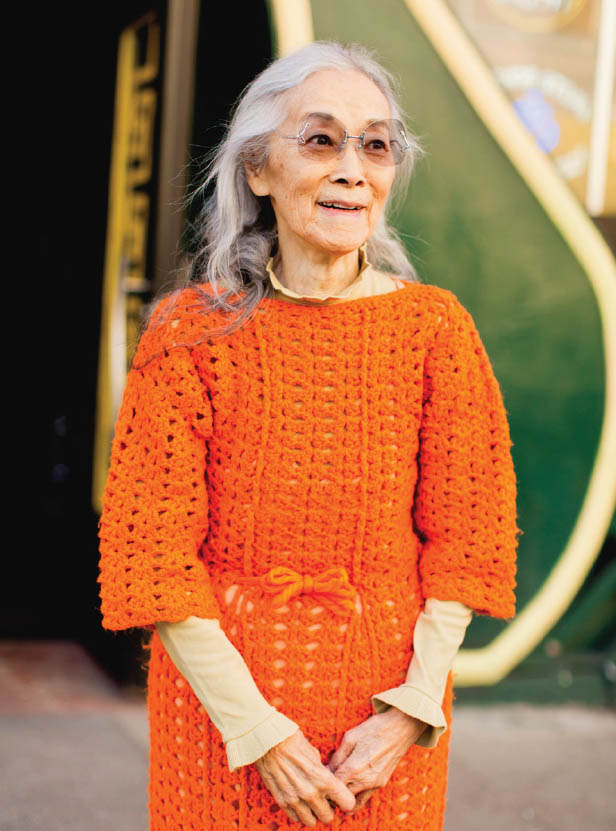

On another day, we toured Chinatown with Polka Dot while she modeled a few knit dresses that her late sister Fann had knitted for her over the years, paired with Sophia Loren–style eyeglasses she’s had since 1990. We stood in front of 842 Washington, her parents’ first rental, where Fann, the eldest sibling, was born. Fann started knitting for her in the 1980s. “She would constantly knit or crochet,” Polka Dot said. “And since she had three sons, the knitting didn’t go very far.” Therefore, Polka Dot was the main recipient of Fann’s original designs—dresses, vests, decorative collars, and scarves.

During the Great Depression, Fann and her dad would walk around the corner to Sam Wo, a local institution, around two a.m. to fill two big pots with leftover jook (rice porridge), noodles, and Chinese doughnuts, which they would eat for breakfast the next morning. “Otherwise, we would’ve gone hungry,” she said. Of Fann, Polka Dot said: “She was my surrogate mother. As the oldest, by default, she had to take care of us younger ones.”

We ducked into Impressions Orient, a gift shop that’s a regular stop on Polka Dot’s walking tours, so she could change into another outfit. She modeled her combination on Waverly Avenue: a beige crocheted dress with a ruffled turtleneck underneath, the mellow colors contrasted with a citrus yellow knit pom-pom beanie and green ribbon at her waist. On her feet were a pair of black flats gifted to her by the 1948 Miss Chinatown Pageant winner, Penny Lee Wong; she added an elastic band across the top to secure the slippers. The outfit wasn’t just fashionable—it felt like a unique product of Fann’s familial love and Polka Dot’s artistic engineering.

Over the years, Polka Dot has become a role model and a friend. She came to our photo exhibit at Legion, an art gallery in Nob Hill. The event at the gallery unfolded into an after-party at the Tonga Room, a legendary tiki bar inside the Fairmont Hotel and one of Polka Dot’s old haunts, a place for special date nights. Her last visit was twenty years ago; she was happy that it’s basically remained the same.

She joined us on the dance floor, while a cover band played Rihanna’s “Umbrella” on a floating stage atop the bar’s indoor pool. When our friend Pete Lee motioned to her that he was ready to walk her home, she said, “Can you wait five more minutes?” so she could squeeze in one more song.