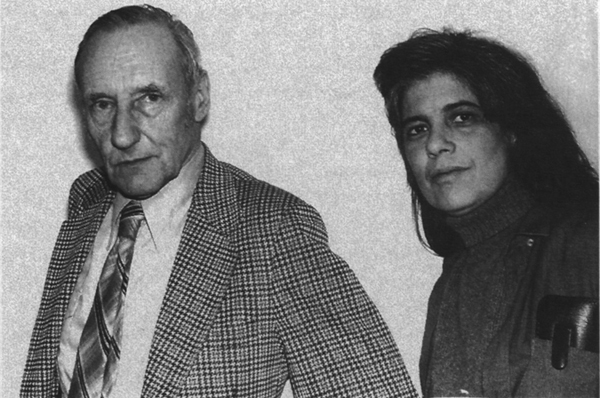

DINNER WITH SUSAN SONTAG, STEWART MEYER, AND GERARD MALANGA: NEW YORK 1980

BOCKRIS: What is writing?

BURROUGHS: I don’t think there is any definition. Mektoub: It is written. Someone asked Jean Genet when he started to write, and he answered, “At birth.” A writer writes about his whole experience, which starts at birth. The process begins long before the writer puts pencil or typewriter to paper.

SUSAN SONTAG: Do you write every day?

BURROUGHS: I feel terrible if I don’t; it’s a real agony. I’m addicted to writing. Do you?

SONTAG: Yes. I feel restless if I don’t write.

BURROUGHS: The more you write the better you feel, I find.

SONTAG: I’ve trained myself to be able to produce some writing that I tell myself quite sincerely is never going to be published. Sometimes something comes out of those things.

BURROUGHS: People will get ahold of them unless you destroy them. Papa Hemingway got caught short with a whole trunkload of stuff!

SONTAG: Do you write on the typewriter?

BURROUGHS: Entirely. I can hardly do it with the old hand. I remember that Sinclair Lewis was asked what to do about becoming a writer and he always said, “Learn to type.”

STEWART MEYER: I remember waking up at the Bunker and hearing the typewriter going like thunder. James Grauerholz told me every morning Bill just gets up, has coffee and cake, and hits the typewriter …

BURROUGHS: The world is not my home, you understand. I am primarily concerned with the question of survival—with Nova conspiracies, Nova criminals, and Nova police. A new mythology is possible in the Space Age, where we will again have heroes and villains, as regards intentions towards this planet. I feel that the future of writing is in space, not time—

SONTAG: This book [Cities of the Red Night], which is 720 pages long, did you just write it out? I’m not asking if you revise. Is your method to write it out and then you have a version to revise, or do you write it in pieces?

BURROUGHS: I used a number of methods, and some of them have been disastrously wrong. In this book I tended to go ahead and write a hundred pages of first draft and then I’d get bogged down in revisions. What I do personally is make ten-page hops. I do a version of a chapter, go over it a couple of times, get it approximately the way I want it, and then go on from there, because I find that if I let it pile up I suddenly get a sickening feeling of overwrite. The whole matter of writer’s block often comes from overwrite. You see, they’ve overwritten themselves, whereas they should have stopped, gone back and corrected. No writer who’s worth his salt has not experienced the full weight of writer’s block.

BOCKRIS: How long did it take you to write your book about cancer?

SONTAG: That was easy and fast. Everything is hard for me, but it was easy. I was inspired. When you’re really full of a subject and you’re thinking about it all the time, that’s when the writing comes, also when you’re angry. The best emotions to write out of are anger and fear or dread. If you have emotions like that you just sail.

GERARD MALANGA: I used to think it was love until love took a third place.

SONTAG: Love is the third. The least energizing emotion to write out of is admiration. It is very difficult to write out of because the basic feeling that goes with admiration is a passive contemplative mood. It’s a very big emotion, but it doesn’t give you much energy. It makes you passive. If you use it for something you want to write, some strange languor creeps over you, which militates against the aggressive energy that you need to write, whereas if you write out of anger, rage, or dread, it goes faster.

BOCKRIS: William, have you ever written anything out of admiration?

BURROUGHS: I don’t know what this term means. It does seem to me an anemic emotion.

SONTAG: Bill, suppose you agreed, which maybe you couldn’t even conceive of doing, to write about Beckett. Somebody offered you a situation at which you said, yes, I’d like to say what I want to say about Beckett, and my feeling about Beckett is mainly positive. I think that’s harder to get down in a way that’s satisfactory than when you’re attacking something.

BURROUGHS: I don’t see what’s being said here at all.

SONTAG: Victor asked me how long it took to write the little book about illness. I wrote it in two weeks because I was so angry I was writing out of rage at the incompetence of doctors and the ignorance and mystifications and stupidities that caused people’s deaths, and that just pulled me along. Whereas I just finished writing an essay on something I really adore, Syberberg’s seven-hour movie about Hitler, and it took months to write.

BURROUGHS: I see what you mean, but it doesn’t correspond to my experience.

SONTAG: I think you write more exclusively out of some kind of objection or admonitory impulse.

BURROUGHS: A great deal of my writing which I most identify with is not written out of any sort of objection at all, it’s more poetic messages, the still sad music of humanity, my dear, simply poetic statements. If I make a little bit of fun of control with Dr. Schaeffer, the Lobotomy Kid, they say, “This dark pacifist who’s paranoid, who’s motivated completely by rejection of technology.” This is a bunch of crap. I just make a little skit that’s all. I am so sick of having this heavy thing laid on me where I just make a little slapstick and someone comes upon me with this “Oh, God, he’s rejecting everything!” shit. I always get this negative image from critics, but the essays in Light Reading for Light Years will make me sound like some sort of great nineteenth-century crank who thought that brown sugar was the answer to everything and was practicing something he called brain breathing. You know, he believed in Reich’s orgone box. I think the real end of any civilization is when the last eccentric dies. The English eccentric was one of the great fecund figures. They’re the lazy men. One man just took to his bed and died from sheer inertia, another would just walk around his estate and he was so lazy that he would have to eat the fruit without plucking it, see, which caused a lot more trouble than if he had actually plucked it. Yes, the English eccentrics were a great breed.

William and Susan after dinner at my apartment. Photo by Gerard Malanga

SONTAG: There are southern eccentrics.

BURROUGHS: Oh, by heavens yes, living on their crumbling estates controlled by their slaves …

DINNER AT BURROUGHS’ APARTMENT: BOULDER 1977

BOCKRIS: Why do you feel that writing is still behind painting?

BURROUGHS: There is no invention that has forced writers to move, corresponding to photography, which forced painters to move. A hundred years ago they were painting cows in the grass—representational painting—and it looks just like cows in the grass. Well, a photograph could do it better. Now one invention that would certainly rule out one kind of writing would be a tape recorder that could record subvocal speech, the so-called stream of consciousness. In writing we are always interpreting what people are thinking. It’s just a guess on my part, an approximation. Suppose I have a machine whereby I could actually record subvocal speech. If I could record what someone thought, there’d be no necessity for me to interpret.

BOCKRIS: How would this machine work?

BURROUGHS: We know that subvocal speech involves actual movement of the vocal cords, so it’s simply a matter of sensitivity. There is a noise connected with subvocal speech, but we can’t pick it up. They probably could do it within the range of modern technology, but it hasn’t been done yet.

BOCKRIS: People absorb and repeat the words of rock songs, which make them very effective. Do you think the printed word can become a more effective tool for communication than it is? People do not go around reciting passages of books in their heads.

BURROUGHS: Yes, they do.

BOCKRIS: Not a lot of people.

BURROUGHS: A lot of them don’t know where what’s in their heads came from. A lot of it came from books.

BOCKRIS: However, words accompanied by music tend to have a bigger effect.

BURROUGHS: This fits right into the bicameral brain theory. If you can get right to the nondominant side of the brain, you’ve got it made. That’s where the songs come from that sing themselves in your head, the right side of the brain. Curiously enough, the most interesting thing about Julian Jaynes’ book The Origins of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind is all Jaynes’ clinical evidence on people who’ve had various areas destroyed. The nondominant side of the brain can sing, but it can’t talk. You can say to it: “Okay, if you can’t say it, sing it.”

BOCKRIS: When did you first meet Brion Gysin?

BURROUGHS: He’d just come back from the Sahara and I went to see an exhibit of his paintings. I met him then. He was a tremendously powerful personality and I was very much impressed with the paintings. I didn’t really get to know him until he came to Paris in 1958. Then I saw his paintings and he was the one who taught me everything I know about painting. He said, “Writing is fifty years behind painting,” and started the cut-up method, which is simply applying the montage method of writing which had been used in painting for fifty years. As you see, painters are now getting off the canvas with all these happenings. I suppose that writing will eventually get off the page following painting. What exactly will happen then I don’t know. They may start writing things in real life. A crime writer will actually go out and shoot people. There’s been a lot of talk about crimes incited by writing, but actually very few authenticated cases of anyone who has committed a crime as a result of reading a work of fiction. Any number of crimes have been committed by people who’ve read about it in the newspapers. Like the man who killed eight nurses in Chicago and then some kid in Arizona got the idea that this might be a good thing to do and killed five women. So all the censorship arguments should be applied first to the daily press because they’re the ones that actually cause people to commit crimes. This man who shot Deutsches [a Communist student leader] in Berlin said he’d gotten the idea from the assassination of King, so the daily press, as far as causing crimes goes, is the real offender, and not the works of fiction. People read a work of fiction and they know it’s a work of fiction. They don’t necessarily rush out and do these things.

BOCKRIS: What is Gysin’s interest in writing?

BURROUGHS: He said, “Well, here’s a simple little thing—the cut-ups—painters have been doing it for fifty years, why don’t you writers try it?” He wants to bring writing up to where painting is. The montage method is much closer to the facts of actual human perception than representational writing, which corresponds to cows-in-the-grass painting.

BOCKRIS: How do you feel about using the tape recorder at the moment?

BURROUGHS: I did some experiments with tape recorders, but using a tape recorder for composition has never worked for me. In the first place, talking and writing are quite different. So far as writing goes I do need a typewriter. I have to write it down and see it rather than talk it. I know that some writers get their notes together for a chapter, then get it into a tape recorder. They got a secretary who brings that back to them and then they make some corrections.

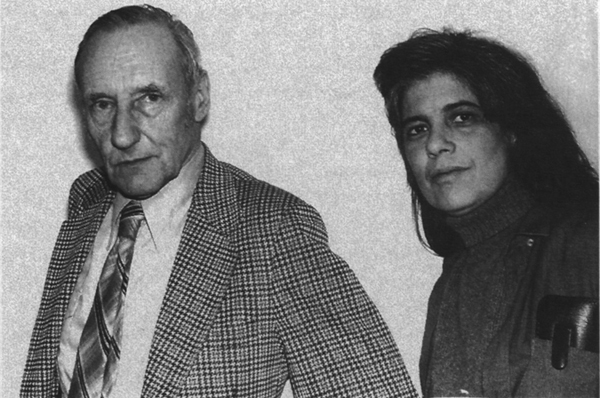

Burroughs smiles for the camera in the BBC Chelsea Hotel documentary directed by Nigel Finch, New York City. Photo: Victor Bockris

BOCKRIS: Have you ever taped television?

BURROUGHS: Lots of times. I had tapes of television shows, then I did all these experiments of putting the soundtrack of one television show onto another similar one and people would come in and it would take ten minutes before anyone realized there was anything wrong if the programs were at all similar. Say the soundtrack of one western on another, they work uncannily well. There’s a shot just where it should be and so on. Then there’ll be a moment and people will say wait a minute there’s something wrong there. But it has taken fifteen or twenty minutes before someone has realized this is not the soundtrack that went with that particular program. It’s very amusing.

A LETTER FROM CARL WEISSNER: MANNHEIM, WEST GERMANY 1974

In 1966 I was living at l-3a Mühltalstrasse, Heidelberg, West Germany, in a room about the size of a 3rd-class passenger berth of an Estonian saltpeter freighter on the Riga-Valparaiso run. On June 6, at precisely 8.20 P.M., there was a knock on the door. I opened the door and for a fraction of a second before the hall light went out I caught a glimpse of a tall thin man, about 52 years of age, black suit black tie white shirt w/ black needle stripes black phosphorescent eyes black hat. He looked like Opium Jones.

“Hello,” he said in a voice hard and black as smoked metal.

“Hello, Mr. Burroughs,” I said. “Come in.”

He had come from Paris where he had worked on the soundtrack of Chappaqua, with Conrad Rooks. He took three or four steps and stood by the narrow table in front of the window. He put his hands into his pockets and in one smooth movement brought out two reels of mylar tape and put them on the table.

“Got your tape recorder?” he asked.

“Yes.”

“Let’s compare tapes.”

We played his tapes, then some of mine. Nothing was said. Except at one point he stopped his tape, wound it back for a second or two, and played it again. “You hear that?” he asked. “…‘wiring wiring’… It’s the voice of a friend of mine from the south. Haven’t seen him in twenty years. Don’t know how his voice got on there.”

Then we put a microphone on the table and took turns talking to the tape recorder switching back and forth between tracks at random intervals. We played it all back and sat there listening to our conversation:

“The other veins crawl through mine,” he said. Adjusting his throat microphone. Breathing heavily in the warm anaesthetic mist that filled the old Studio.

“Mind you take film. I want to see that. Grammars of distant differential tissue.

“Agony to breathe here.

“Muy alone in such tense and awful silence and por eso have I survived.

“Echoes of sticky basements. From Lyon to Marseilles. Fossil flesh stormed the exits.

“Carl made words in the air without a throat without a tongue. Vestigial penis figures to the sky now isn’t that cute?

“Yes that’s what makes a real 23 as the focus snaps like this & you are actually there.

“Junkie there at the corner flicking empty condoms H caps KY tubes?

“Now what I was telling you about the Police Parallele. The Manipulator takes pictures for 24 hours. His eyes unbluffed unreadable.

“His face melted under the flickering arc lights. Most distasteful thing I ever stand still for.”

At approximately 1.30 A.M. Mr. Burroughs took a cab to the Hotel Kaiserhof. At approximately 1.36 the receptionist handed him the key to his room. It was the key to room 23.

DINNER AT BURROUGHS’ APARTMENT: BOULDER 1977

BOCKRIS: When you were writing Naked Lunch you told Jack Kerouac that you were apparently an agent from some other planet who hadn’t gotten his messages clearly decoded yet. Has all your work been sent from other places and your job been to decode it?

BURROUGHS: I think this is true with any writer. The best seems to come from somewhere … perhaps from the nondominant side of the brain. There’s a very interesting book I mentioned earlier called The Origins of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind by Julian Jaynes. His theory is that the first voices were hallucinated voices, that everyone was schizophrenic up till about 800 B.C. The voice of God came from the nondominant side of the brain, and the man who was obeying these voices, to put it in Freudian terms, would have a superego and an id but no ego at all. Therefore no responsibility.

This broke down in a time of great chaos, and then you got the concepts of morality, responsibility, law, and also divination. If you really know what to do, you don’t have to ask. Jaynes’ idea was that early men knew what to do at all times; they were told, and this was coming from outside, as far as they were concerned. This was not fancy, because they were actually seeing and hearing these gods. So they didn’t have anything that we call “I.” Your “I” is a completely illusory concept. It has a space in which it exists. They didn’t have that space, there wasn’t any “I” or anything corresponding to it.

BOCKRIS: Is human nature to blame for …

BURROUGHS: Human nature is another figment of the imagination.

BOCKRIS: What do I mean when I say human nature?

BURROUGHS: You mean there is some implicit way that people are. I don’t think this is true at all. The tremendous range in which people can be conditioned would call in question any such concept.

BOCKRIS: There seems to be an alarmingly large number of meaningless words polluting our language.

BURROUGHS: The captain says, “The ship is sinking.” People say he’s a pessimist. He says, “The ship will float indefinitely.” He’s an optimist. But this has actually nothing to do with whatever is happening with the leak and the condition of the ship. Both pessimist and optimist are meaningless words. All abstract words are meaningless. They will lump such disparate political phenomena as Nazi Germany, an expansionist militaristic movement in a highly industrialized country, together with South Africa and call them both fascism. South Africa is just a white minority trying to hang on to what they got. It’s not expansionist. They’re not the same phenomena at all. To call both fascist is like saying there’s no difference between a wristwatch and a grandfather clock.

BOCKRIS: Do you think what appears in newspapers, on television, and in daily intercourse is quite meaningless?

BURROUGHS: Absolutely, because they’re always using such generalities. There is no such entity as Americans, there’s no such entity as “most people.” These are generalities. All generalities are meaningless. You’ve got to pin it down to a specific person doing a specific thing at a specific time and space. “People say …” “People believe …” “In the consensus of informed medical opinion …” Well, the minute you hear this, you know if the man can’t pin down who he’s talking about, where and when, you know you’re listening to meaningless statements.

The consensus of medical opinion was that marijuana drove people insane. Well, we pinned Anslinger down on this. All he could come up with was one Indian doctor who stated that he considered the use of marijuana grounds for incarceration in a mental institution. Therefore it was proven that marijuana drove people insane. One should always challenge a generality. Police Chief Davis of Los Angeles wrote a column on pornography. He says, “Studies have shown that pornography leads to economic disaster.” What studies? Where are these wondrous studies?

BOCKRIS: In your new novel, Cities of the Red Night, you write about body transference.

BURROUGHS: I’m convinced the whole cloning book was a fraud, but it’s within the range of possibilities: and there’s no doubt that what you call your “I” has a definite location within the brain, and if they can transplant it, they can transplant it. In fact, what these transplant doctors are working up to is brain transplants.

BOCKRIS: Have you had any out-of-the-body experiences?

BURROUGHS: Who hasn’t?

BOCKRIS: I’m not quite sure what they are.

BURROUGHS: I’ll give you one right now. You’re staying where?

BOCKRIS: The Lazy L Motel.

BURROUGHS: What does your room look like?

BOCKRIS: Standard motel, double bed, rust-colored rug and …

BURROUGHS: You’re having an out-of-the-body experience. Right now you’re there.

BOCKRIS: I was standing in the middle of the room looking around it.

BURROUGHS: That’s good, isn’t it? But dreams are also, of course …

BOCKRIS: Have you ever dreamed that you were someone else?

BURROUGHS: Frequently. I looked in a mirror and found that I was black. Looked down at my hands and they were still white. This is quite common. It’s usually someone I don’t know. I look at my face and it’s quite different, and not only my face but my thoughts. I’ve come in in the middle of someone else’s identity and feel usually quite comfortable with the person I’ve become.

BOCKRIS: Often I find when I tell a lie it becomes true. I say to someone, “Well, no, I’m awfully sorry I can’t come over tonight because I’m going to see so and so,” and I actually end up going to see so and so, but it wasn’t true at all when I said it.

BURROUGHS: I’ve had that happen lots of times.

BOCKRIS: I’ve become more careful what lies I tell.

BURROUGHS: Talking about writers who write things that actually happen, take Graham Greene. I went to Algiers during the Algerian war in 1956. All the planes were jammed with people trying to leave and I couldn’t get out. I was staying in this dumpy hotel, and I used to eat every day in this Milk Bar which had big jars of passion fruit, various banana splits, all kinds of juices and little sandwiches; there were pillars made of mirror all around. About a week after I left, a bomb exploded in that Milk Bar and there was this terrible mess. Brion [Gysin] was there very shortly after the bomb exploded and he later described the scene. People were lying around with their legs cut off, spattered with maraschino cherries, passion fruit, ice cream, brains, pieces of mirror and blood. Now, at approximately the same time this happened, Graham Greene was writing The Quiet American in Saigon, and he described an explosion in a Milk Bar in almost exactly the same details. So, years later when I was reading the book and came to the Milk Bar explosion scene, I said, “Uh oh, time to duck,” because I knew exactly what was going to happen.

DINNER WITH NICOLAS ROEG, LOU REED, BOCKRISWYLIE AND GERARD MALANGA: NEW YORK 1978

BURROUGHS [talking about Graham Greene’s Brighton Rock]: It’s a good book. It’s got a strange shape. He’s suddenly saying you’re a bad Catholic. That’s a very good book.

NICOLAS ROEG: I’m interested by your liking Brighton Rock. It is an overlooked book in literature. Hands up those who read Brighton Rock? Excellent! Go to the top of the form. And stay there till I come for you.

BOCKRIS: What’s that one about?

BURROUGHS: It’s about boys—seventeen-year-old boooooooiiiiiyyyysss. With razor blades strapped on their fingertips or something. I never got into that razor blade thing exactly … Do you know a writer named Denton Welch?

ROEG: Who was that?

BURROUGHS: He was sort of the original punk, and his father called him Punky. He was riding on a bicycle when he was twenty, and some complete cunt hit him and crippled him for the rest of his life. He died in 1948 at the age of thirty-three after writing four excellent books. He was a very great writer, very precious.

ROEG: Punk is a very good word. It’s an old English word. Shakespeare used it and it originally meant prostitute. In fact, it used to appear in the forties in the movies. I guess it must have different connotations in America. I love the subtle differences in the language. Americans are able to cut it down and make it much slicker. Where we say lift you say elevator. Where you say automobile we say car.

Lou Reed came in with his Chinese girlfriend and some guitarists, sat down and immediately launched into a playful attack. He told Burroughs that he’d read his great essay called Kerouac in High Times and asked why he didn’t write more stuff like that.

BURROUGHS: I write quite a lot.

Reed wondered whether Bill had written any more books with a straight narrative since Junky.

BURROUGHS: Certainly. Certainly. The Last Words of Dutch Schultz, for example. And my new novel, Cities of the Red Night, has a fairly straight narrative line.

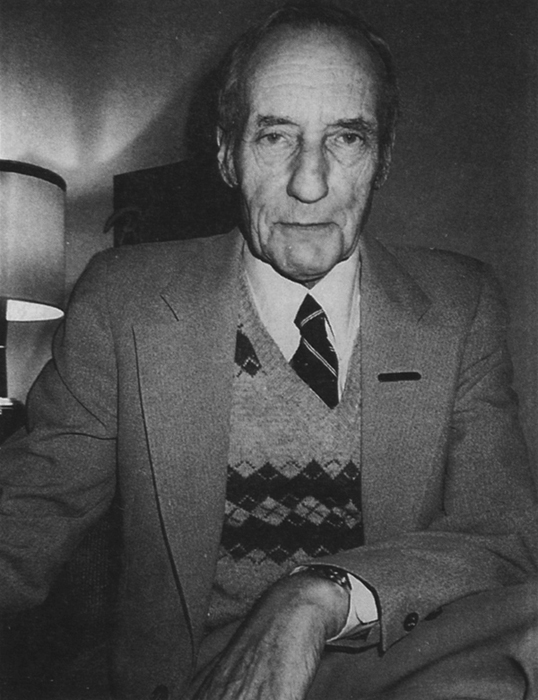

Peter Beard, Nicolas Roeg, and William Burroughs at my apartment after their conversations. Photo by Bobby Grossman

I got up, went across the room and returned with a copy of The Last Words of Dutch Schultz. Reed asked if it was an opera.

BURROUGHS: No man, no. You don’t know about the last words of Dutch Schultz? You obviously don’t know. They had a stenographer at his bedside in the hospital taking down everything he said. These cops are sitting around asking him questions, sending out for sandwiches, it went on for 24 hours. He’s saying things like, “A boy has never wept nor dashed a thousand kim,” and the cops are saying, “C’mon, don’t give us that. Who shot ya?” It’s incredible. Gertrude Stein said that he outdid her. Gertrude really liked Dutch Schultz.

BOCKRIS-WYLIE: Do you know where Genet is now?

BURROUGHS: Nobody knows. The people who know him just don’t seem to know where he is. Brion knows him very well. I thought he was one of the most charming people I ever met. Most perceptive and extremely intelligent. While his English is nonexistent and my French very bad, we never had the slightest difficulty in communicating. That can be disastrous. You get a real intellectual French type like Sartre, the fact that I didn’t speak French would just end the discussion right there.

BOCKRIS-WYLIE: Where’d you meet Genet?

BURROUGHS: I met him in Chicago at the convention.

BOCKRIS-WYLIE: What was he like? What was he wearing?

BURROUGHS: He was wearing corduroy trousers and some old beat up jacket, and no tie. For one thing he’s just completely there, sincere and straight-forward. Right there is Genet. When people were chased out of Lincoln Park, there was a cop right behind Genet with a nightstick and Genet turned around and did like this, “I’m an old man.” And the guy veered away, didn’t hit him. There were more coming up, so he went into an apartment at random, knocked at a door, and someone said, “Who’s there?” He said, “MONSIEUR GENET!” The guy opened the door and it turned out he was writing his thesis on Genet.

BOCKRIS-WYLIE: How do you feel about Cocteau? Proust?

BURROUGHS: I think Proust is a very great writer. Much greater writer than Cocteau or Gide. I was in the army hospital in the process of getting discharged. And because of the bureaucracy it took four months for this to come through, so I had the time to read Remembrance of Things Past from start to finish. It is a terrifically great work. Cocteau appears as a minor poseur next to this tremendous work of fiction. And Gide appears as a prissy old queen.

BOCKRIS: I understand you met Céline shortly before he died?

BURROUGHS: This expedition to see Céline was organized in 1958 by Allen Ginsberg who had got his address from someone. It is in Meudon, across the river from Paris proper. We finally found a bus that let us off in a shower of French transit directions: “Tout droit, Messieurs …” Walked for half a mile in this rundown suburban neighborhood, shabby villas with flaking stucco—it looked sort of like the outskirts of Los Angeles—and suddenly there’s this great cacophony of barking dogs. Big dogs, you could tell by the bark. “This must be it,” Allen said. Here’s Céline shouting at the dogs, and then he stepped into the driveway and motioned to us to come in. He seemed glad to see us and clearly we were expected. We sat down at a table in a paved courtyard behind a two-story building and his wife, who taught dancing—she had a dancing studio—brought coffee.

Céline looked exactly as you would expect him to look. He had on a dark suit, scarves and shawls wrapped around him, and the dogs, confined in a fenced-in area behind the villa, could be heard from time to time barking and howling. Allen asked if they ever killed anyone and Céline said, “Nooo. I just keep them for the noise.” Allen gave him some books, Howl and some poems by Gregory Corso and my book Junky. Céline glanced at the books without interest and laid them sort of definitively aside. Clearly he had no intention of wasting his time. He was sitting out there in Meudon. Céline thinks of himself as the greatest French writer, and no one’s paying any attention to him. So, you know, there’s somebody who wanted to come and see him. He had no conception of who we were.

Allen asked him what he thought of Beckett, Genet, Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Henri Michaux, just everybody he could think of. He waved this thin, blue-veined hand in dismissal: “Every year there is a new fish in the literary pond.

“It is nothing. It is nothing. It is nothing,” he said about all of them.

“Are you a good doctor?” Allen asked.

And he said: “Well … I am reasonable.”

Was he on good terms with the neighbors? Of course not.

“I take my dogs to the village because of the Jeeews. The postmaster destroys my letters. The druggist won’t fill my prescriptions.…” The barking dogs punctuated his words.

We walked right into a Céline novel. And he’s telling us what shits the Danes were. Then a story about being shipped out during the war: the ship was torpedoed and the passengers are hysterical so Céline lines them all up and gives each of them a big shot of morphine, and they all got sick and vomited all over the boat.

He waved goodbye from the driveway and the dogs were raging and jumping against the fence.

BOCKRIS: Who else do you read?

BURROUGHS: A writer who I read and reread constantly is Conrad. I’ve read practically all of him. He has somewhat the same gift of transmutation that Genet does. Genet is talking about people who are very commonplace and dull. The same with Conrad. He’s not dealing with unusual people at all, but it’s his vision of them that transmutes them. His novels are very carefully written.

BOCKRIS: Is there anyone in particular who influenced your work?

BURROUGHS: I’d say Rimbaud is one of my influences, even though I’m a novelist rather than a poet. I have also been very much influenced by Baudelaire, and St.-John Perse, who in his turn was very much influenced by Rimbaud. I’ve actually cut out pages of Rimbaud and used some of that in my work. Any of the poetic or image sections of my work would show his influence.

MALANGA: Are you very self-critical or critical of others?

BURROUGHS: I’m certainly very self-critical. I’m critical of my work. And I do a great deal of editing. Sinclair Lewis said if you have just written something you think is absolutely great and you can’t wait to publish it or show it to someone, throw it away. And I’ve found that to be very accurate. Tear it into small pieces and throw it into someone else’s garbage can. It’s terrible!

MALANGA: Do you have a lot of secrets?

BURROUGHS: I would say that I have no secrets. In the film The Seventh Seal the man asked Death, “What are your secrets?” Death replied, “I have no secrets.” No writer has any secrets. It’s all in his work.

MALANGA: In an article by your son that appeared in Esquire you were quoted as saying, “All past is fiction.” Maybe you could explain this further.

BURROUGHS: Sure. We think of the past as being something that has just happened, right? Therefore, it is fact; but nothing could be further from the truth. This conversation is being recorded. Now suppose ten years from now you tamper with the recordings and change them around, after I was dead. Who could say that wasn’t the actual recording? The past is something that can be changed, altered at your discretion. [Burroughs points to the two Sonycorders facing each other that are taping this dinner.] The only evidence that this conversation ever took place here is the recording, and if those recordings were altered, then that would be the only record. The past only exists in some record of it, right? There are no facts. We don’t know how much of history is completely fiction. There was a young man named Peter Webber. He died in Paris, I believe, in 1956. His papers fell into my hands, quite by chance. I attempted to reconstruct the circumstances of his death. I talked to his girlfriend. I talked to all sorts of people. Everywhere I got a different story. He had died in this hotel. He had died in that hotel. He had died of an OD of heroin. He had died of withdrawal from heroin. He had died of a brain tumor. Everybody was either lying or covering up something; it was a regular Rashomon [reference is to the Japanese film in which everybody gives a different account of the story; even the dead man who they bring back with a medium tells a completely different story] or they were simply confused. This investigation was undertaken two years after his death. Now imagine the inaccuracy of something that was one hundred years ago! The past is largely a fabrication by the living. And history is simply a bundle of fabrication. You see, there’s no record this conversation ever took place or what was said, except what is on these machines. If the recordings were lost, or they got near a magnet and were wiped out, there would be no recordings whatever. So what were the actual facts? What was actually said here? There are no actual facts.

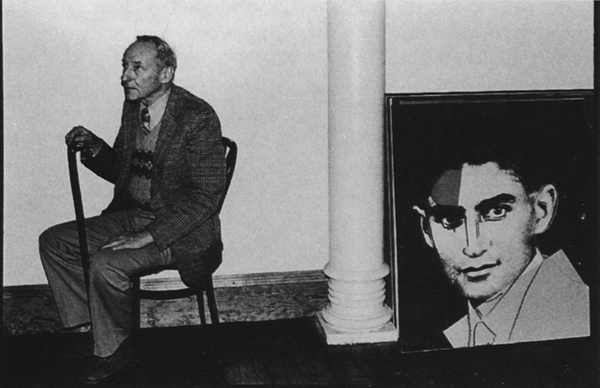

Burroughs being photographed by Warhol for a portrait at The Factory while a Wharholed Franz Kafka looks on discerningly. Photo by Bobby Grossman

MALANGA: IS ESP something that has helped you in your writing?

BURROUGHS: Yes, I think all writers are actually dealing in this area. If you’re not to some extent telepathic, then you can’t be a writer, at least not a novelist where you have to be able to get into someone else’s mind and see experience and what that person feels. I think that telepathy, far from being a special ability confined to a few psychics is quite widespread and used every day in all walks of life. Watch two horse traders. You can see the figures taking shape … “Won’t go above … won’t go below.” Card players pride themselves on the ability to block telepathy, the “poker face.” Anybody who is good at anything uses ESP.

Interrupting Bill again, Lou asked him which one of his books was his favorite.

BURROUGHS: Authors are notoriously bad judges of their own work. I don’t really know …

Reed claimed that he had gone out and bought Naked Lunch as soon as it was published. He then asked what Burroughs thought of City of Night by John Rechy and Last Exit to Brooklyn by Hubert Selby, adding that these two books couldn’t have been written without what Burroughs had done.

BURROUGHS: I admire Last Exit to Brooklyn very much. You can see the amount of time that went into the making of that book. It took seven years to write. And I like Rechy’s work very much too. We met him out in L.A. Very pleasant man, I thought; we only saw him for about half an hour.

Reed asked whether Rechy had read Burroughs.

BURROUGHS: I didn’t ask him, no.

Changing his tack radically, Lou said he’d heard that Burroughs had cut his toe off to avoid the draft.

BURROUGHS [chuckling]: I would prefer to neither confirm nor deny any of these statements.

Lou then wanted to know why Bill had used the name William Lee on Junky.

BURROUGHS: Because my parents were still alive and I didn’t want them to be embarrassed.

Reed asked whether Burroughs’ parents read.

BURROUGHS: They might have.

Reed told Bill that he felt Junky was his most important book because of the way it says something that hadn’t been said before so straightforwardly. Reed then asked Bill if he was boring him.

BURROUGHS [staring blankly at the table]: Wha …?

THREE SPEECHES

ALLEN GINSBERG: I nominated William Burroughs for membership in the American Institute of Arts and Letters, of which I’m a member, but I don’t think he was accepted. So apparently the establishment still hasn’t fully accepted him, although he is Supreme Establishment himself as far as literature: I think he’s one of the immortals; he’s had an enormous effect on succeeding generations of writers directly, and indirectly through my work and Kerouac’s work in terms of his ideas, his ideologies, his Yankee pragmatic spiritual investigations. But directly—more importantly—through his own spectral prose. I think Burroughs should get the Nobel Prize. Genet never got it. Obviously Genet deserves it. Just Burroughs and Genet themselves are really two contenders for world honors.

MILES: William is a writer who has gone through a long period of addiction and survived. He spent twelve years as a drug addict and is one of the few people who have ever been able to really transform it into something solid, and use it. It really enabled him to understand a control system, and when he applied his understandings of the control systems to literature, which is essentially what he did, and what Brion helped him to do by introducing him to the cut-up technique, for instance, he automatically entered into a public field of information, exposing control systems, which is what politics has been all about, the CIA, and word addiction and everything else Bill talks about, so his actual art and his literature have been about subjects which transcend literature and move out into everyday political experience as experienced by our generation, but not by his generation, oddly enough, which is why he’s so important to the underground press and people like that. He is still probably the most relevant writer alive. He has that extraordinary combination of elements in his background which makes him that. He’s able to transform things, and that’s why people respond to him. He also has that cynical funny angle like Céline that appeals to a certain type of person who has taken a lot of drugs maybe. He’s actually a humorist to a lot of people who transcend the superficial level of a lot of present-day humor that we get fed on. William is probably the funniest person you can come upon. As a writer, I think he’s in a very crucial phase right now. He’s obviously always going to be important, but he hasn’t achieved the kind of success that he deserves. His career parallels Kerouac’s in this respect. His early books are really significant but no one realized that until about six years later. Then he got really famous and kept on writing. But Kerouac’s later books weren’t as good. I think Bill’s capable of better than that. He could grow to produce something that is better than Naked Lunch. I don’t think William ever needs to justify himself as a writer. He’s written a lot. He hasn’t just written Ulysses and Finnegans Wake. William’s had an absolute rebirth since he came back to the States. He’s a very different person now, much more confident in his position as some kind of literary celebrity and I think it was moving back to New York that enabled him to do that. Shortly after he went back he told me, “It’s really good, but one standing ovation is enough.”

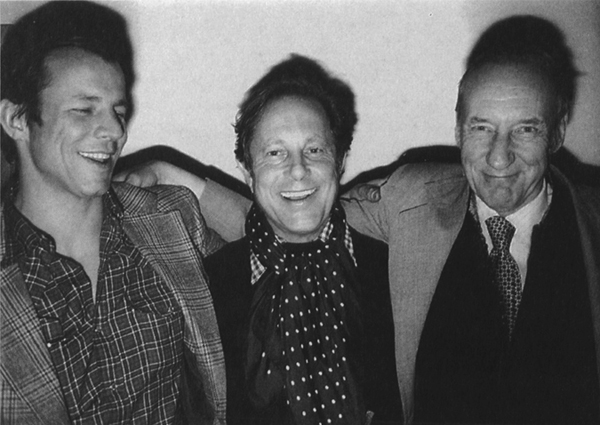

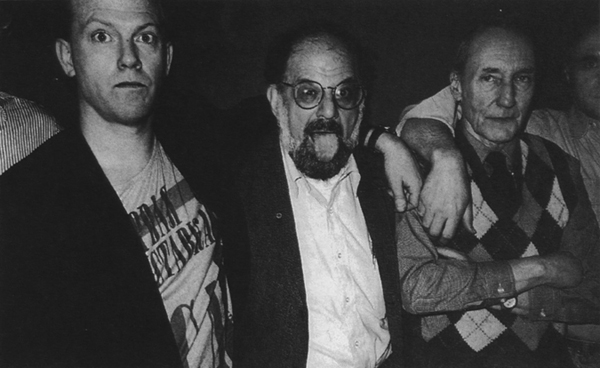

Andrew Wylie with Allen Ginsberg and William Burroughs at the Bunker, after he became their new literary agent, giving both Ginsberg’s and Burroughs’s careers a significant boost, New York City, 1986. Photo: Victor Bockris

Certainly of the Beat Generation, Bill was the one that no one was ever able to put tabs on, because his approach was always so very different. For a start, Burroughs was in a funny kind of way openly gay. Even Allen’s gayness was different. His was a kind of proselytizing, campaigning gayness, whereas Bill’s was very different. Bill was always the absolute antithesis of what the society was doing, which is why he stayed out of America. He couldn’t have made it here. Allen could make it. William went through a lot of very heavy times. Don’t forget most people thought he was dead when he arrived back in the States. They thought he and Kerouac had just snuffed.

BURROUGHS: To my way of thinking the function of the poet is to make us aware of what we know and don’t know we know. Allen Ginsberg’s opinions, his writings, his works, and his outspoken attitudes towards sex and drugs, were once fully disreputable and unacceptable and now have become acceptable and in fact respectable. And this occasion is an indication of this shift in opinion. You remember it was extremely unacceptable once to say that the earth was round, and I think that this shift whereby original thinkers are accepted is very beneficial both to those who are accepting them and to the thinkers themselves. Somerset Maugham said that the greatest asset that any writer can have is longevity, and I think that in another ten or fifteen or twenty years, Allen may be a very deserving recipient of the Nobel Prize.

DINNER WITH LOU REED: NEW YORK 1979

BOCKRIS: Was Kerouac the writer you felt closest to in your generation?

BURROUGHS: He encouraged me to write when I was not really interested in it. There’s that. But stylistically, or so far as influence goes, I don’t feel close to him at all. If I should mention the two writers who had the most direct effect on my writing, they would be Joseph Conrad and Denton Welch, not Kerouac. In the 1940s, it was Kerouac who kept telling me I should write and call the book I would write Naked Lunch. I had never written anything after high school and did not think of myself as a writer and I told him so. I had tried a few times, a page maybe. Reading it over always gave me a feeling of fatigue and disgust and aversion toward this form of activity, such as a laboratory rat must experience when he chooses the wrong path and gets a sharp reprimand from a needle in his displeasure centers. Jack insisted quietly that I did have talent for writing and that I would write a book called Naked Lunch. To which I replied, “I don’t want to hear anything literary.” During all the years I knew Kerouac I can’t remember ever seeing him really angry or hostile. It was the sort of smile he gave in reply to my demurs, in a way you get from a priest who knows you will come to Jesus sooner or later—you can’t walk out on the Shakespeare Squad, Bill.

BOCKRIS: When did you write Naked Lunch?

BURROUGHS: In the summer of 1956 I went to Venice and made a few notes there, and then I had this trip to Libya. I went to the American Embassy there and said, “Well, how can I get out of here? All the planes are full, can I just get on a train?”

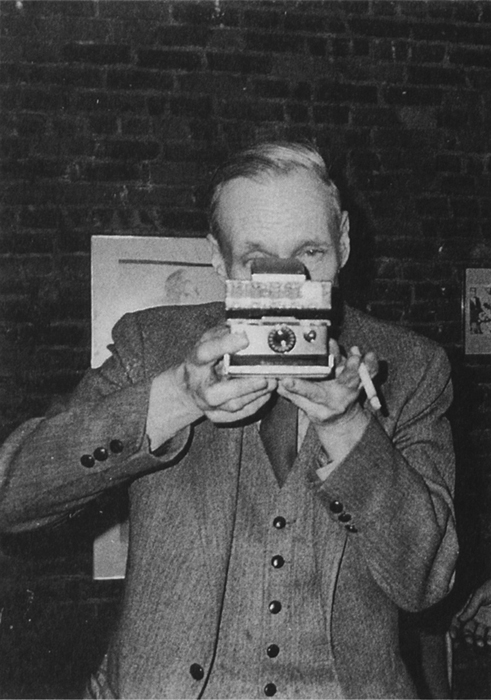

Burroughs takes aim with Polaroid Big Shot,

New York City, 1982.

“Oh no,” they said, “you have to have an exit permit.” And so I went around. I remember going to this courtyard with porticos around and looking for some official who was supposed to do this and he wasn’t ever there. In fact, he did not exist, as I came to suspect. So finally somebody told me, “Listen, just get on a train and leave.” That’s what I did, and when I got to the Moroccan border the French guard sort of looked at my papers, but I was leaving, see, and he didn’t want to make a fuss so he just stamped it and said, “Go ahead,” and I was back in Morocco. I could have been sitting around for months waiting for an exit visa according to the American Embassy: “Oh, you have to have this. It would be very inadvisable to leave without it. We couldn’t help you …” So it was just at this time that I sat down and I had lots of notes that I’d made in Scandinavia, Venice, and Tangier previously, and started writing, and I wrote and I wrote and I wrote. I’d usually take majoun every other day and on the off days I would just have a bunch of big joints lined up on my desk and smoke them as I typed. I was getting up pretty early; I’d work most of the day, sometimes into the early evening. I used to go out and row in the bay every day for exercise. I had this room for which I was paying, God, $15 a month for a nice room on the garden of the Hotel Muneria there with a big comfortable bed and a dresser and a washstand and everything, with a toilet just around the corner. When Jack came to Tangier in 1957 I had decided to take his title and much of the book was already written.

BOCKRIS: When you were writing then, did you have any intimation of the effect it might have?

BURROUGHS: None whatever. I doubted that it would ever be published. I had no idea that the manuscript had any value. I was terrifically turned on by what I was writing.

BOCKRIS: Did Kerouac have all his experiences so he could write about them?

BURROUGHS: I’d say that he was there as a writer, and not as a brakeman or whatever he was supposed to be. He said, “I am a spy in somebody else’s body. I am not here as what I am supposed to be.”

BOCKRIS: Is that what ultimately made him unhappy?

BURROUGHS: Not at all. It’s true of all artists. You’re not there as a newspaper reporter, a doctor or a policeman, you’re there as a writer.

BOCKRIS: He seemed to lose contact with people, so that he ended up …

BURROUGHS: All writers lose contact. I wouldn’t say that he was particularly miserable. He had an alcohol problem. It killed him.

BOCKRIS: When was the last time you saw him?

BURROUGHS: 1968. I had been at the Democratic Convention in Chicago, and Esquire had placed at my disposal a room in the Delmonico Hotel to write the story. Kerouac came to see me, and he was living at that time in Lowell. He had these big brothers-in-law, one of whom ran a liquor store, and they were shepherding him around. He was really hittin’ it heavy, because he got another room in the hotel and stayed overnight, and he was ordering up bottles of whiskey and drinking in the morning, which is a practice I regard with horror. So I talked to the Greek brothers … you know … “Terrible he’s hittin’ it like this and not doing any work …” That was the last time.

BOCKRIS: Did you have much conversation?

BURROUGHS: Well, he’s hittin’ it heavy. That was when he went on the Buckley show, and I told him, “No, Jack, don’t go, you’re not in any condition to go.” But he did go that same night. I said, “I’m not even going to go along.” Allen Ginsberg went. It was, of course, a disaster. Jack and his in-law brothers left the next day. That was the last time I ever saw him. He was dead a year later. Cirrhosis, massive hemorrhage.

Lou Reed seemed extremely interested in Kerouac and wanted to know why he had ended up in such bad shape, sitting in front of a television set in a tee shirt drinking beer with his mother. What had happened to make Kerouac change?

BURROUGHS: He didn’t change that much, Lou. He was always like that. First there was a young guy sitting in front of television in a tee shirt drinking beer with his mother, then there was an older fatter person sitting in front of television in a tee shirt drinking beer with his mother.

Addressing Bill as Mr. Burroughs, Lou asked if Kerouac’s books were published because he had slept with his publisher. He wondered if that happened a lot in the literary world.

BURROUGHS: Not nearly as much as in painting. No, thank God, it is not very often that a writer will have to actually make it with his publisher in order to get published, but there are a lot of cases of young artists who will have to sleep with an older woman gallery owner or something to get their first show, or get a grant. I can definitely assure you that I have never had sex with any of my publishers. Thank God, it has not been necessary.

DINNER WITH MAURICE GIRODIAS, GERARD MALANGA, AND GLENN O’BRIEN: BOSTON 1978

MAURICE GIRODIAS: I like Bill Burroughs very much. He is about the nicest person I have ever met in this literary game. He is a very naive man. There is something naive about him that explains a lot of the mythological strangeness that is attached to his image and reputation.

BOCKRIS: What were the circumstances of your publishing Naked lunch?

GIRODIAS: Allen Ginsberg brought me the first manuscript of Naked Lunch in 1957. He was acting as Burroughs’ friendly agent. It was such a mess, that manuscript! You couldn’t physically read the stuff, but whatever caught the eye was extraordinary and dazzling. So I returned it to Allen saying, “Listen, the whole thing has to be reshaped.” The ends of the pages were all eaten away, by the rats or something.… The prose was transformed into verse, edited by the rats of the Paris sewers. Allen was very angry at me, but he went back to Bill, who was leading a very secret life in Paris, a gray phantom of a man in his phantom gabardine and ancient discolored phantom hat, all looking like his moldy manuscript. Six months or so later he came back with a completely reorganized, readable manuscript, and I published it in 1959. Burroughs was very hard to talk to because he didn’t say anything. He had these incredibly masklike, ageless features—completely cold-looking. At this time he was living with Brion Gysin and Gysin would do all the talking. I’d go down to Gysin’s room and he would talk and show me his paintings and explain things. Then we’d go back to Burroughs’ room and all three of us would sit on the bed—because there were no chairs—and try to make conversation. It was really funny. The man just didn’t say anything. I had my Brazilian nightclub and the first time Burroughs came there—it was soon after I met him—I was in the cellar giving an impromptu lesson in the tango to one of John Calder’s assistants who came over every summer for these tango lessons. I’m down there with her alone when Burroughs suddenly comes down the stairs and he says: “Girodias … I don’t want to disturb anything at all that’s going on down here, but …” It turned out the Beat Hotel had been raided and he’d been busted for possession of some hash or something and he wanted my help. He kept saying: “These French cops …” After I published Naked Lunch, I published a book of his every six months. The Soft Machine, The Ticket That Exploded. I never had much editorial conversation with him, actually none. He’d just bring in the manuscript and I’d knock it out. I think he was doing it to pay the rent. He really needed the money.

BURROUGHS: I would like to lay to rest for all time the myth of the Burroughs millions which has plagued me for many years. One reviewer has even gone as far as to describe me as “the world’s richest ex-junkie” at a time when I had less than $1,000 in the bank. My grandfather, who invented the hydraulic device on which the adding machine is based, like many inventors received a very small share of the company stock; my father sold the few shares in his possession in the 1920s. My last bequest from the Burroughs estate on the death of my mother in 1970 was the sum of $10,000.

BOCKRIS: Do you ever get worried that being a writer provides a pretty thin income?

BURROUGHS: It’s gotten very thin. I’ve sat down many times and tried to write a bestseller but something always goes wrong. It isn’t that I can’t bring myself to do it or that I feel I’m commercializing myself or anything like that, but it just doesn’t work. If your purpose is to make a lot of money on a book or film, there are certain rules to observe. You’re aiming for the general public, and there are all sorts of things the general public doesn’t want to see or hear. A good rule is never ask the general public to experience anything they cannot easily experience. You don’t want to scare them to death, knock them out of their seats, and above all, you don’t want to puzzle them.

GLENN O’BRIEN: Maybe we have to go into show business.

BURROUGHS: We already have, for Godsakes, with all these readings. That’s the way I make a living, man!

O’BRIEN: We’ll probably wind up as stand-up comedians or something.

BURROUGHS: My God! I already have been described as a stand-up comedian.

MALANGA: Would you ever like to apply your knowledge of telepathy in areas other than writing? Let’s say, the stock market?

BURROUGHS: A deep misuse of these powers is always going to fuck you up. I used to do some gambling. Horseraces. I’ve had dreams and intuitions, and something always went wrong. That is, I had a number but I didn’t have the horse, or I had the horse and I didn’t have the number. I think this is a misuse of telepathy. If you’re trying to take something from this level and bring it down to this level, you’re going to get fucked every time. The classical story about that was The Queen of Spades—a Russian story about someone who was getting telepathic tips on gambling and, of course, finally got fucked.

MALANGA: SO you think using telepathy for gambling purposes is a disrespect of one’s powers?

BURROUGHS: All gamblers use telepathy for gambling purposes; all gambling works on telepathy. But it’s a tricky area. And gambling is something I absolutely don’t want to know about anymore, or let’s say the use of telepathic powers or extrasensory perception in those areas, because I know sooner or later you’re going to get the shaft and you’ll well deserve it.

BOCKRIS: How do they absorb used-up money?

BURROUGHS: They burn it. Ted Joans had an uncle who worked in the combustion department and he figured out some way to get this stuff out under his coat and he had a big stack of it under his porch. His wife saw somebody going by in an old beat-up car and she said, “It’d be nice to get one,” and he said, “Well, pretty soon we will,” and he told her. Next thing he knew they were knocking on his door. Telephone. Telegraph. Television. Tell a woman. He got twenty years.

DINNER WITH TENNESSEE WILLIAMS: NEW YORK 1977

BURROUGHS: When someone asks me to what extent my work is autobiographical, I say, “Every word is autobiographical, and every word is fiction.” Now what would your answer be on that question?

TENNESSEE WILLIAMS: My answer is that every word is autobiographical and no word is autobiographical. You can’t do creative work and adhere to facts. For instance, in my new play there is a boy who is living in a house that I lived in, and undergoing some of the experiences that I underwent as a young writer. But his personality is totally different from mine. He talks quite differently from the way that I talk, so I say the play is not autobiographical. And yet the events in the house did actually take place. I avoid talking about writing. Don’t you, Bill?

BURROUGHS: Yes, to some extent. But I don’t go as far as the English do. You know this English bit of never talking about anything that means anything to anybody … I remember Graham Greene saying, “Of course, Evelyn Waugh was a very good friend of mine, but we never talked about writing!”

WILLIAMS: There’s something very private about writing, don’t you think? Somehow it’s better, talking about one’s most intimate sexual practices—you know—than talking about writing. And yet it’s what I think we writers live for: writing. It’s what we live for, and yet we can’t discuss it with any freedom. It’s very sad … Anyway, I’m leaving America, more or less for good. Going to England first.

BURROUGHS: For good or for bad …

WILLIAMS: Well, when I get to Bangkok it may be for bad, I don’t know [laughter]. And after I get through with this play in London, I should go to Vienna. I love Vienna. You remember the twenties?

BURROUGHS: Oh heavens, yes.

WILLIAMS: I only ask because there are few people living who do … That’s the sad thing about growing old, isn’t it—you learn you are confronted with loneliness.…

BURROUGHS: One of the many.

WILLIAMS: Yes, one of the many—that’s the worst, yes.

Burroughs and Williams in the drawing room of the latter’s suite at the Elysee Hotel. Photo by Michael McKenzie

BURROUGHS: After all, if there wasn’t age, there wouldn’t be any youth, remember.

WILLIAMS: I’m never satisfied to look back on youth, though … not that I ever had much youth.

BURROUGHS: Writers don’t, as a rule.

WILLIAMS: I was in Vienna in 1936. Remember the Römanische Baden?

BURROUGHS: The Roman Baths. I went to them … they’re lovely, too.

WILLIAMS: Right near where the Prater used to be.

BURROUGHS: I’ve ridden on that ferris wheel in the park.

WILLIAMS: Me, too.