DINNER WITH GERARD MALANGA: NEW YORK 1974

BURROUGHS: There couldn’t be a society of people who didn’t dream. They’d be dead in two weeks.

MALANGA: Do you have a certain technique for notating dreams?

BURROUGHS: If you don’t write them down right away, in many cases you’ll forget them. I keep a pencil and paper by my bed. I’ve had dreams where I’ve continued episodes—“to be continued”—and if they’re goodies you want to get back there as quick as possible, but I always make a point, even though I want to get back there, of making just a few notes, otherwise the next day you’ll lose the whole thing. If I just make two words here, that’ll get me back there. There’s some basic difference between memory traces of a dream and the actual event. Now I’ve had this happen: I’d wake up and I’m too lazy to get up and I’ll go over it ten times in my mind and say, “Well, sure I’ll certainly remember that.” Gone. So memory traces are lighter for dreams than they are for so-called events. I keep a regular dream diary. Then, if they’re particularly interesting or important I’ll expand them into dream-scenes that might be usable in a fictional context by making a longer typewritten account. Sometimes I get long sequential narrative dreams just like a movie, and some of these have gone almost verbatim into my work. In some ways the most fruitful dreams have been when I find a book or magazine with a story in it I can read. It can be hard to remember, but sometimes I get a whole chapter that way and the next day I just sit down and write it out. The opening chapter of Cities of the Red Night—The Health Officer—was such a chapter, a dream that I had about a cholera epidemic in Southwest Africa, and I just sat down and wrote it out. I was reading rather than writing. And then the story They Do Not Always Remember, which appeared in Exterminator, was also a dream. I don’t know if other writers have them, but it’s certainly a writer’s dream.

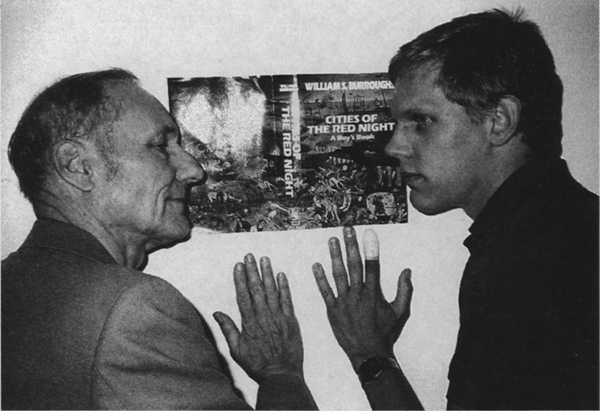

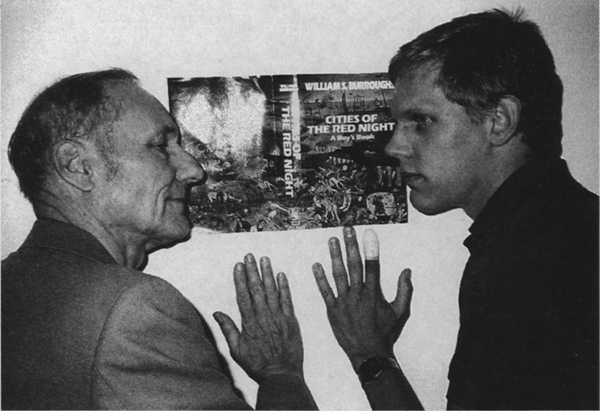

William and James with first proof copies of Cities of the Red Night, which Grauerholz worked on closely with Burroughs. Note the subtitle, A Boy’s Book, which was later removed from the jacket and title page. Photo by Victor Bockris

MALANGA: Learning to get hold of this material is a technical matter, so I presume it’s something you get better at.

BURROUGHS: You can get feedback: I’ve had a dream and I write something about it; then, as a result of writing something, I have a further dream along the same lines. I’m getting feedback between what I write and what I’m dreaming about.

BOCKRIS: Have you always had this habit of waking up a lot during the night?

BURROUGHS: I’ve always been a very light sleeper. The slightest thing wakes me up. I wake up five or six times in the course of an average night. I get up and maybe have some milk or a glass of water, or write down some dreams, if I have any. I was once in a room with another person who set the mattress on fire. His mattress, but I was the one that woke up. Oooooh, smoke! Wide awake. I’ve always defied anyone to get in the room with me without waking me up. Just the presence of another person is enough. Sometimes if I can’t go back to sleep I’ll read for a while. I have about six books by my bed that I’m reading. And it’s the only thing to do if you have a real nightmare. Get up and fix yourself a cup of coffee or tea and stay up for ten minutes to reorient yourself, because if you go right back to sleep you’re going right back into it. Sometimes I’ll have three real nightmares in a row, so I say now it’s time to stop, break the chain. I will get up, maybe have some tea, smoke a joint, anything to break it up. The best thing to do is get up and have something to drink.

BOCKRIS: I’ve had nightmares in which it seems that somebody or something has gotten into the apartment.

BURROUGHS: I had this experience with James. When I first came back to New York we were sleeping in a loft over on Broadway and I had this dream: There was a knock at the back door, I went to the back door and there was this person known as Marty. I’ve got a little chapter in Cities about this, and he was there with a chauffeur, a bearded man, who was so drunk he could hardly stand up. It was all sort of 1890s, see. “Come along to the Metropole and have some bubbly,” as he put it, some champagne. The Metropole was the old hangout in the 1890s. It was around Times Square. And I said, “Oh Marty, no.” I said, “You know …”

He said, “What’s the matter, your old pals aren’t good enough for you anymore?”

“I don’t remember that we were exactly pals, Marty!” I replied. This is someone I’d known, sort of real bad news. Then he said, “Let me in, I’ve come a long way,” and he shoved his way into the apartment. Then I had pictures of James covered with a white foam and I was trying to wake up, saying, “James! James!” When I did finally wake up he was out of bed and he had picked up a pipe threader that was there and I said, “What’s the matter?” He answered, “I just felt that there was someone in the apartment.”

“Well,” I said, “someone indeed was in the apartment. That was Marty.” So I used Marty as a character in Cities. Marty Blum.

In 1977, Bob Dylan invited Burroughs to join the Rolling Thunder tour to participate in some way in the movie Renaldo and Clara. Burroughs declined on the grounds that the offer was too ill-defined to be worth his while. During this period he had two dreams about Dylan.

In the first dream he had the idea that he should suggest a benefit concert for junkies. After seeing Dylan’s Madison Square Garden benefit performance for Rubin Hurricane Carter, Burroughs had a second dream that told him to forget the idea on the grounds that he would not be able to hold the attention of the vast audience that Dylan commands.

BOCKRIS: When did you first meet Bob Dylan?

BURROUGHS: In a small café in the Village, around 1965. A place where they only served wine and beer. Allen had brought me there. I had no idea who Dylan was, I knew he was a young singer just getting started. He was with his manager, Albert Grossman, who looked like a typical manager, heavy kind of man with a beard, and John Hammond, Jr., was there. We talked about music. I didn’t know a lot about music—a lot less than I know now, which is still very little—but he struck me as someone who was obviously competent in his subject. If his subject had been something that I knew absolutely nothing about, such as mathematics, I would have still received the same impression of competence. Dylan said he had a knack for writing lyrics and expected to make a lot of money. He had a likable direct approach in conversation, at the same time cool, reserved. He was very young, quite handsome in a sharp-featured way. He had on a black turtleneck sweater.

DINNER WITH STEWART MEYER: NEW YORK 1979

MEYER: Bill, when I make something up out of the clear blue sky where is it coming from?

BURROUGHS: Man, nothing comes out of the clear blue sky. You’ve got your memory track … everything you’ve ever seen or heard is walking around with you. Remember the line “All a Jew wants to do is doodle a Christian girl, you know that yourself,” from Naked Lunch? I heard that line verbatim. I thought to myself, “Goooooood Lord, now I’ve heard it all.” But the line came in handy.

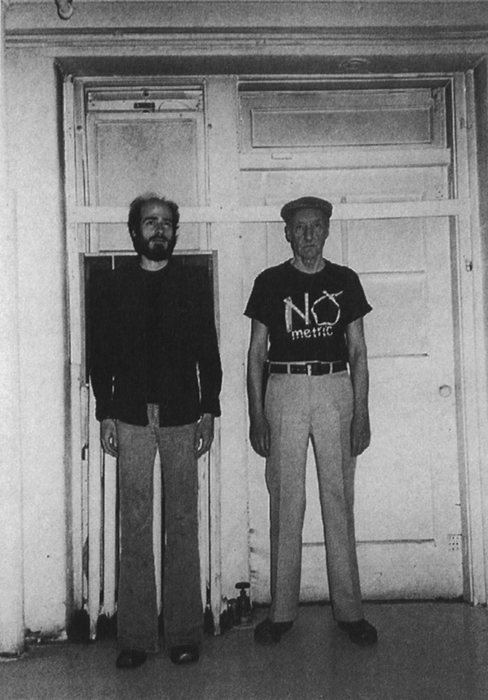

Stewart Meyer and Burroughs after dinner at the Bunker. Note Burroughs’ NO METRIC T-shirt. Photo by Victor Bockris

MEYER: Right away?

BURROUGHS: Give or take thirty years.

MEYER: What stops the flow for me is, I’m sitting there writing and dreaming freely, then I start to watch myself.

BURROUGHS: Who’s watching you when you’re watching yourself?

MEYER: Is a tightrope walker a tightrope walker all the time?

BURROUGHS: Well, yes. I’ll just cower in the Bunker and leave that stuff to the professionals.

MEYER: Too bad the subconscious mind can’t be triggered like the conscious.

MEYER: What? How?

BURROUGHS: Do nothing. Only secret to tapping the subconscious mind is do nothing. This corresponds to the Buddhist thing.

MEYER: But it isn’t a direct trigger.

BURROUGHS: The conscious and subconscious work completely differently.

MEYER: How necessary do you think the conscious mind is?

BURROUGHS: I think the conscious mind will eventually be phased out as a failed experiment. Think of it: no conscious egos. All that negativity done away with.

BOCKRIS: What do you believe in?

BURROUGHS: Belief is a meaningless word. What does it mean? I believe something. Okay, now you have someone who is hearing voices and believes in these voices. It doesn’t mean they have any necessary reality. Your whole concept of your “I” is an illusion. You have to give something called an “I” before you speak of what the “I” believes.

BOCKRIS: What’s your greatest strength and weakness?

BURROUGHS: My greatest strength is to have a great capacity to confront myself no matter how unpleasant. My greatest weakness is that I don’t. I know that’s enigmatic, but that’s sort of a general formula for anyone, actually.

DINNER WITH ALLEN GINSBERG: NEW YORK 1980

BOCKRIS: What frightens you most?

BURROUGHS: Possession. It seems to me this is the basic fear. There is nothing one fears more or is more ashamed of than not being oneself. Yet few people realize even an approximation of their true potential. Most people must live with varying degrees of the shame and fear of not being fully in control of themselves.

Imagine that the invader has taken over your motor centers. There you are at a party, press cameras popping away, and suddenly you know you are going to exhibit yourself and shit at the same time. You try to run, your legs won’t move. Your hands, however, are moving, unzipping your fly.

And all this is within the range of modern technology. Professor Delgado can make a subject pick something up by electric brain stimulation. No matter how hard the subject tried to resist the electronic command, he was helpless to intervene.

No doubt this good thing has come to the attention of the dirty trick department. So Brezhnev shits in the UN and Reagan exposes himself in front of a five-year-old child at a rally. Perhaps they decided to outlaw that one like the Jivaro [a tribe of headhunting Indians found mostly in Ecuador] outlawed the use of curare darts in feud killings. It’s such a horrible death. And the humiliation inflicted by MC [Motor Control]. Sanction is literally a fate worse than death, a horrible maimed existence … madness or suicide.

It shouldn’t happen to your worst enemy because the way this universe is connected, it could happen back at YOU.

Centipedes frighten me a good deal, although this is not an actual phobia where people are incapacitated by the sight of a centipede. I simply look around for something with which to combat this creature. I have a recurring nightmare where some very large poison centipede, or scorpion about this long, suddenly rushes on me while I’m looking about for something to kill it. Then I wake up screaming and kicking the bedclothes off. The last time was in Greece in August 1973. I was with my mother in a rather incestuous context. I think the ideal situation for a family is to be completely incestuous. So this is a slightly incestuous connection with my mother and I said, “Mother, I am going to kill the scorpion.” It was a big thing, about this long. At this point the scorpion suddenly rushed upon me, and I had nothing to kill it with. I was looking around for a shoe or something. I woke up kicking the bedclothes off. Then I remember another dream, which is in Exterminator, where someone had one of these fucking things about eighteen inches long and I said, “Get away from me!” I had a snub-nosed .38 in my hand. And I said, “Get away from me with that fucking thing or I’ll kill you!” This was a combination scorpion-centipede about six inches long that runs very quickly.

BOCKRIS: Have you ever had an actual run-in with a scorpion?

BURROUGHS: I’ve had them around and I’ve killed them. I’ve never had one try to attack me.

BOCKRIS: Have you ever come upon one, unexpectedly in bed?

BURROUGHS: In southeast Texas I found them on the wall in my room; it drove me crazy. I can’t sleep if I think there’s a scorpion in the room. If I don’t succeed in killing it, then it keeps me awake all night. It’s an awful electric feeling. I mean the idea of one getting on me is horrible. It’s something you can’t empathize with at all. It’s completely disgusting. They’ve got no feeling at all; the thought of touching one gives me the absolute horrors—all those legs! A friend of mine told me his most horrible experience in the Pacific during World War II. He was in one of those jungle hammocks with a net over it. He woke up and a six-inch-long centipede was on the side of his face pulling his cheek all out of shape. He reached up and grabbed it. He’s holding this fucking thing in one hand, trying to open the zipper with the other hand! He said it’s like holding a red hot wire! This thing was writhing around biting his hand, and finally he got the zipper open and threw it out.

BOCKRIS: Could we employ insects in a useful way?

BURROUGHS: I don’t know any useful work for a centipede.

BOCKRIS: Couldn’t they be regular assassins if well trained?

BURROUGHS: Fu Manchu used to have a poison insect routine. He put some sort of perfume on someone that would attract this venomous creature. I think one was a big red spider that he called a Red Bride.

GINSBERG: Have you ever had a dream in which you murdered somebody and the guilt was hidden and you had heavy anxiety?

BURROUGHS: Oh, sure. I’ve hurt somebody, sometimes they’ve just hidden around …

GINSBERG: This is an archetypal thing because I had that the other night. In this case there was an elderly woman who was a concierge who didn’t like me and I was sucking up to her trying to get a room, or trying to be at home in that country, and I was afraid that she already knew that I had this secret corpse somewhere in my past I hadn’t quite acknowledged to myself yet, I hadn’t quite remembered, what was the crime I committed, but I knew that it was some dreadful secret that would be uncovered any minute at the tip of my tongue or hers. But meanwhile we sat and had tea while I asked her for a room, and then she looked at me and said, “By the way, how would you like to fuck me?” And I said, “Sure,” because I realized I better play up to her or she would realize I had killed a woman or something …

BURROUGHS: How many’d you kill?

GINSBERG: Oh, just the entire race by obliterating them in my mind and not fucking them at all. Having not had sex with a woman since 1967.

BURROUGHS [impatiently]: That’s metaphysical, purely metaphysical. [Bored]: You’re talking about insecurity. [Annoyed]: What are we talking about?!

GINSBERG: I woke up then and realized it was only a dream. Then I began examining why I would have that dream unless I had some hypocrisy or some deception?

BURROUGHS: Oh, good heavens, my dear! I don’t know. I always have dreams of being arrested or tried or something like that.

GINSBERG: But the dream of concealing a murder is one I’ve had about four or five times, colored by dread and anxiety, a spiritual, poetic Watergate, you know. So I searched: was it 1968 in my testimony at the Chicago trials I said nobody intended violence? Was it income tax evasion?

BURROUGHS: You’re too spooky …

GINSBERG: Was it Vajrayana delights? Or what! Was it actually being gay and not making out with women and not having children?

BURROUGHS: So what?

GINSBERG: Or was it that the night before I’d read a story which had that plot?