DINNER WITH ANDY WARHOL AND MARCIA RESNICK: NEW YORK 1980

BOCKRIS: Bill was married twice. Ilse Burroughs was his first wife. Like W. H. Auden he married a woman to get her out of Nazi occupied Europe. W. H. Auden married Thomas Mann’s daughter, Elsa Mann, right?

BURROUGHS: Refuting any imputation of anti-Semitism.

ANDY WARHOL: And she lived on the Lower East Side.

BOCKRIS: And Ilse Burroughs is still alive.

WARHOL: No, no, but Mrs. Auden lived on the Lower East Side, St. Marks Place. God!

BURROUGHS: Mrs. Burroughs certainly does not live on the Lower East Side! She lives in some fashionable place in Italy.

BOCKRIS: She’s apparently very wealthy.

BURROUGHS: I don’t see how she could be wealthy. Certainly not from me.

MARCIA RESNICK: Did she marry you to get a green card or something?

BURROUGHS: Yes. To get away from the Nazis. She came to America and her first job was to work for Ernst Toller. Toller was a left-wing playwright with a certain reputation at that time. She was working as his secretary and she always kept very regular hours, getting back at exactly one o’clock after she’d gone out to lunch. On this day she met an old refugee on the street, someone she knew from the old Weimar days, so they had a coffee and she was delayed about ten minutes. When she got back she sat down at the typewriter, “and then,” she makes a gesture, “I get it up the back of my neck and I know he is hanging up somewhere.”

So she goes to the bathroom and finds Toller is hanging on the other side and manages to get him down. But he was already dead. He’d attempted suicide several times before but always arranged it so someone got there in time to turn off the gas, or call an ambulance. The old refugee did him in.

Burroughs has often been asked about his attitudes toward women. “I think anybody incapable of changing his mind is crazy,” he recently answered. Although Bill generally surrounds himself with male company, there are a number of women whom he sees regularly and has a real affection for: Mary McCarthy, who lives in Paris with her diplomat husband Jim West; Susan Sontag; Normandy-based American socialite Panna O’Grady; Italian litterateur Fernanda Pivano; English editor Sonia Orwell; publishing doyen Mary Beach; and Felicity Mason, a.k.a. Anne Cummings, author of The Love Habit: Sexual Confessions of an Older Woman [about which William has written: “Anne Cummings is the forerunner of the truly emancipated woman of the future, who is casual about her emancipation. Love affairs, she feels, should provide divertissement, not disillusionment. Sex is something to enjoy, a means of universal communication that bridges the generation gap.”] are all friends of many years’ standing. Among his younger women friends are poet-teacher Anne Waldman and chanteuse Patti Smith. There are a number of women writers whom Bill considers highly, among them Mary McCarthy, Joan Didion, Susan Sontag, Djuna Barnes, Carson McCullers, Flannery O’Connor, Jane Bowles, Dorothy Parker, Eudora Welty, Isabelle Eberhardt and Colette.

His second wife, whom he accidentally shot and killed, was Joan Vollmer, with whom he had, according to Kerouac, Huncke and Ginsberg, an extremely close, mutually supportive and affectionate relationship.

DINNER WITH BOCKRIS-WYLIE: NEW YORK 1974

BOCKRIS-WYLIE: How’d you feel when you shot your second wife?

BURROUGHS: That was an accident. That is to say, if everyone is to be made responsible for everything they do, you must extend responsibility beyond the level of conscious intention. I was aiming for the very tip of the glass. This gun was a very inaccurate gun, however.

BOCKRIS-WYLIE: But after you shot her did you think, “I’m being controlled by something else and that’s why this happened?”

BURROUGHS: No, I thought nothing. It was too horrific. It’s very complicated to tell you. It was obviously a situation precipitated by some part of myself over which I had, or perhaps have, no control. Because I remember on the day in which this occurred, I was walking down the street and suddenly I found tears streaming down my face. “What in hell is the matter? What in hell is the matter with you?” And then I took a knife to be sharpened which I had bought in Ecuador and I went back to this apartment. Because I felt so terrible, I began throwing down one drink after the other. And then this thing occurred.

BOCKRIS-WYLIE: How did it happen?

BURROUGHS: We’d been drinking for some time in this apartment. I was very drunk. I suddenly said, “It’s about time for our William Tell act. Put the glass on your head.” I aimed at the top of the glass, and then there was a great sort of flash.

BOCKRIS-WYLIE: How far away were you?

BURROUGHS: About eight feet.

BOCKRIS-WYLIE: What’s the first thing you thought when you saw that you’d missed the glass?

BURROUGHS: Lewis Adelbert Marker was there; I said, “Call my lawyer. Get me out of this situation.” I was, as the French say, “bouleversé.” This is a terrible thing that has happened, but I gotta get my ass outta this situation. In other words, what went on in my mind was—I have shot my wife, this is a terrible thing, but I gotta be thinking about myself. It was an accident. My lawyer came to see me. Everyone’s evidently overwhelmed by the situation, in tears, and he says, “Well, your wife is no longer in pain, she is dead. But don’t worry, I, Señor Abogado, am going to defend you.” He said, “You will not go to jail.” I was in jail. “You will not stay in jail. In Mexico is no capital punishment.” I knew they couldn’t shoot me. “This is the district attorney,” he said. “He works in my office, so do na worry.” I got over to the jailhouse. That was something else. I had this fucking gypsy who was a may–or. See, every cell block in the Mexico City jail has a may–or, a guy that runs the cell block, and he said, “Well we got decent people in here and people who will pull your pants off you. I am puttin’ you in with decent people. But for this, I need money.” So then I was in with all these lawyers, doctors, and engineers, guilty or not guilty of various crimes. One of my great friends in the jail was a guy who had been in the diplomatic service who’d been accused of issuing fraudulent immigration papers to people. And they were all just takin’ it easy. We’re eating inna restaurant, we’re getting oysters and everything. All of a sudden the may–or gets on to this. He says, “This prick Burroughs is getting away with something here. We’re gonna send you over to the cell block and I’m gonna put you in a colony where fifteen spastics will fuck you!” So I got over to the other cell block, and I said, “Well, this can’t happen to me, ya know. THIS CAN’T HAPPEN TO ME!” You get this tremendous sense of self-preservation. So I talked to the guy and I said, “Listen, I’ll pay you so much, ya know, not to do these things.” Then the may–or over in the other cell block finds out what I’m doin’. He says he’s cooled the may–or over there. And he’s really putting the pressure on. It was just at this point that I got out. My lawyer got me out. In the nick of time, because they were really puttin’ the pressure on. Some guy—the may–or—came over there and said, “Listen do you wanna go in the colonía? This is the place where all the big bank robbers go and everyone is having big poker games. They got nice beds and all this.” I said, “Man, I don’t wanna sit down and spend my life in this place, I wanna get out of here!” Just at this point my lawyer got me out.

BOCKRIS-WYLIE: After you got out of jail in Mexico, did you split?

BURROUGHS: No. I split about a year later, because I had to go back every Monday by nine o’clock to check in. They could put you back in jail. All these different people who put their thumbprints on things because they couldn’t write, cops and everybody, all had to be there by nine o’clock. This woman would come in and say, “Hello, boys.” A teacher. A bureaucrat. Of course while I was actually in prison I had to be very careful of my reputation. I didn’t want to get known as a queer or anything like that, because that can be a murderous situation. I got some great human statements from the guards. One guard said, “It’s too bad when a man gets in jail because of a woman.”

BOCKRIS-WYLIE: Do you go to porn flicks a lot?

BOCKRIS-WYLIE: Do you tend to get more turned on by men or women?

BURROUGHS: I’ve seen both, I’ve seen nongay and gay porn flicks. Naturally, I’m more turned on by men than women. But if you have a beautiful woman … I saw this one porn flick that had beautiful women in it and that sort of turned me on too. It reminded me of the old days in the whorehouses in St. Louis. I used to come down after having made it with a whore, and the madam would shove me into a little alcove because someone else was coming in. It might be a friend of my father’s. Or even my father himself.

BOCKRIS-WYLIE: How much did it cost in those days?

BURROUGHS: Five dollars.

BOCKRIS-WYLIE: How long did you have?

BURROUGHS: Five dollars gave you a half hour.

Burroughs is often regarded as a misogynist. “In the words of one of the greatest misogynists, plain Mr. Jones in Conrad’s Victory: ‘Women are a perfect curse,’” he wrote in The Job (1968). “I think they were a basic mistake, and the whole dualistic universe evolved from this error. Women are no longer essential for reproduction. And I think American women are possibly one of the worst expressions of the female sex because they’ve been allowed to go further. Love is a con put down by the female sex.”

DINNER WITH BOCKRIS-WYLIE AND MILES: NEW YORK 1974

BOCKRIS-WYLIE: Why’d you get married?

BURROUGHS: It was probably a question of circumstance. I didn’t get married. I had a common-law wife, which is the same actually, because the lawyer told me, “Brother, if you’re living with a woman and she is known as your wife, she is your wife!” Legally speaking. She can get alimony. She has exactly the same rights. She was an extraordinary person, one of the more perceptive and intelligent people I’ve known. Joan, for example, was the first, before I was into writing, or even thinking in these areas, who said that the Mayan priests must have experienced some sort of telepathic method of control.

BOCKRIS-WYLIE: How long did you actually live with her?

BURROUGHS: Three or four years.

BOCKRIS-WYLIE: I still don’t understand how you got together with your wife.

BURROUGHS: There is a certain degree of inertia. You’re living with someone, you seem to be getting along with them very well, and that sets up a relationship. It wouldn’t happen now. Simple inertia. I got something that is understandable to all my junkie friends, namely an ooooold lady.

BOCKRIS-WYLIE: Were you in love with your wife?

BURROUGHS: I find great difficulty in defining what being in love with someone means.

BOCKRIS-WYLIE: Take it as the point where you start to lose power.

BURROUGHS: It’s a very good definition, very good definition indeed, because if you are dependent on the other person … No, I was never in love with her in that sense.

BOCKRIS-WYLIE: Were you ever in love with anyone?

BURROUGHS: Oh, sure, in exactly that sense.

MILES: When Bill was in London he was much more extreme. He might, for example, seriously argue that women had all come from out of space. I really don’t think he would say that these days. Mind you, it wasn’t a metaphor. I think he actually believed it. We had some quite nasty arguments. I felt that I had to talk to him about this because it was making me feel uncomfortable. Apart from anything else, I had to consider whether or not I could bring any girlfriends around. That’s one of the main reasons I didn’t spend a lot of time with Bill throughout the sixties. William actually wanted to surround himself with an all male society and succeeded in doing so, in London anyway. Except when Johnny used to bring back these strange Irish ladies. Occasionally there’d be some fat blonde Irish girl running about and William would sulk in the corner while Johnny was trying to get rid of her. I think it was Johnny’s sister, but she hadn’t got any clothes on and it was a very uncomfortable situation for Bill.

DINNER WITH PATTI SMITH: NEW YORK 1980

Burroughs taped a conversation with Patti Smith for High Times in late 1979. The transcript was too long and the magazine rejected it. There were, however, some interesting exchanges in it. One was about having children. Burroughs said he’d heard a lot of women say they didn’t want to have children. Patti said she’d had one and expressed her personal spartan feeling about it, in that she had no desire to see the child. She hoped that her child would have enough space to develop in and be with someone who would bring it up appropriately. Bill pointed out that there was less and less space and less and less opportunity and that “the more people have in common, the more of them you can get into less space with less friction. It’s a matter of identification also,” he continued. “The more contact you have with someone, if it’s of a positive nature, naturally the easier it is to accept their presence in a limited space.” Smith felt strongly that inspiration created space. She remembered that in school she’d been told that Burroughs’ work was difficult to read, but she hadn’t found it difficult at all when she finally encountered it.

DINNER WITH SUSAN SONTAG AND JOHN GIORNO: NEW YORK 1980

BOCKRIS: Susan, do you still think it’s harder to be a woman in America now than it was two years ago?

SONTAG: It’s harder to be a woman anywhere than it is to be a man. It’s probably less hard in America than in a lot of other places.

BURROUGHS: I think it’s bloody hard to be anything.

SONTAG: We all know that, but on the other hand if I were black and sitting here and you said is it harder and then I said well sure it’s hard anywhere, and then somebody else said well it’s hard to be anything, you might think that was rather beside the point. Of course it’s hard to be anything, but then there are additional disabilities.

BURROUGHS: But when you say it’s hard to be a woman, you’re speaking from a woman’s standpoint, right? Things that might be very hard for you might be very easy for me, and vice versa. One man’s hell is another man’s paradise.

BOCKRIS: When did you meet Jane Bowles?

BURROUGHS: I don’t remember when I first met her. She was someone of extreme charm. It was a number of years later that I read her books and realized what an extremely talented writer she was.

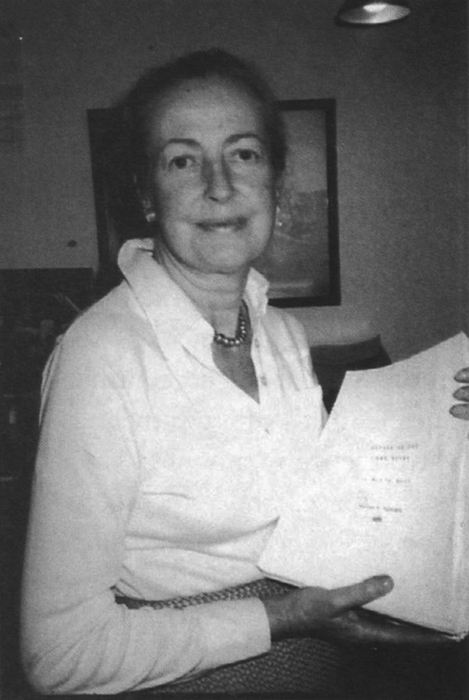

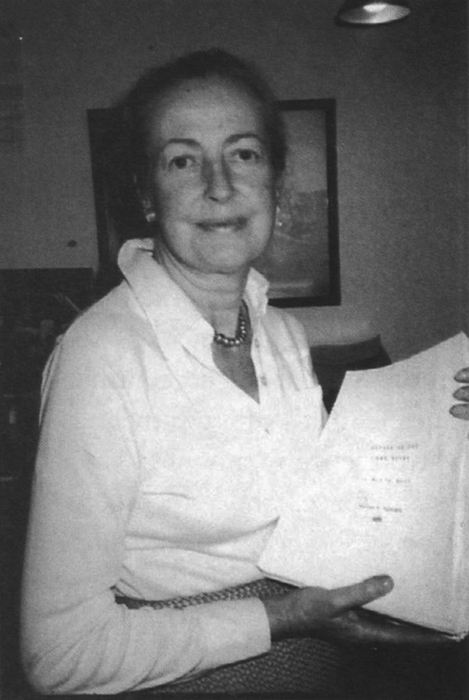

Felicity Mason (a.k.a. Anne Cummings, author of The Love Habit) holding the manuscript of Cities of the Red Night. Photo by Victor Bockris

BOCKRIS: What kind of relationship did she and Paul Bowles have when you knew them?

BURROUGHS: I know nothing about their relationship. My old Uncle Willy always told me, “Never interfere in a boy and girl fight.” And the less you know about the relationship between two people who are married, or who are a couple living together, the better it is. That’s something to stay out of.

BOCKRIS: The gulf between the sexes is growing. Men think it’s harder to be a man while women think it’s harder to be a woman …

BURROUGHS: Such semantic difficulties here. What do you mean by hard to be, and who is to be the judge of this? How hard is it to be what? I think it’s very hard to be a person. I don’t know …

SONTAG: It depends for whom.

BURROUGHS: I think it’s just hard to be myself. It’s hard to draw breath on this bloody planet.

BOCKRIS: Auden said that he was so glad when his sex drive died because it had always been a terrible nuisance to him.

BURROUGHS: Well, if it’s a terrible nuisance to you there must be some conflict connected with it. “God! Thank God that’s ended!” It’s a terrible English thing. They have the same attitude toward life. Life is something you muddle through, and “Thank God this is over,” they say when they’re dying. England is very antisexual. It’s very much to do with the Queen!

BOCKRIS: How were they so successful if they had those two big problems?

BURROUGHS: They didn’t have anything else to do except get out and conquer—you know Serve the Queen, the old Whore of Windsor, she lived to a great age. Eighty-three?

JOHN GIORNO: Ninety-three.

BURROUGHS: I think it was eighty-three, because it was not long enough to occasion comment, which it would have been if she’d lived to ninety-three.

BOCKRIS: Her husband died forty years before she did.

BURROUGHS: The same is true in the western cultures and particularly true in America. Wives outlive their husbands by many years. There’s hubby working away and getting fat and under all this stress and he dies of a heart attack about the age of fifty-five. She then gets the money and lives on for another thirty years, during which she goes around the world with groups of women and they have bridge clubs. There’s all these old biddies, with three or four hundred thousand dollars, and they all live in the same sort of motel. My friend Kells Elvins’ father died and his mother got all that money, $250,000, a hell of a lot in those days. Then she married another one and he died so there was another $300,000. So here’s this old biddy, who has no habits at all, with $550,000 and she went out and established herself in some sort of condominium. They have all sorts of retirement apartments for women of fifty-five or sixty with a lot of money and they play shuffleboard.