DINNER WITH LEGS MCNEIL, JAMES GRAUERHOLZ, ANDY WARHOL, AND RICHARD HELL: NEW YORK 1980

BOCKRIS: I think Pasolini died happy.

BURROUGHS: I don’t think there’s any reason to believe that he died happy at all. The implication is that the boy was paid to kill him. He hit him over the head with a board with nails sticking out of it. Then when he was unconscious the kid backed the car over him. Now the boy himself, who’s still in jail, has never confessed to the fact that he was paid to do this because they said, “Okay, kid, we’ll take care of you; we’ll get you out if you keep your fucking mouth closed.” It was a political thing.

GRAUERHOLZ: He was murdered by the right?

BURROUGHS: Sure. I don’t think there’s much doubt about it. I talked to somebody who’s a friend of Felicity Mason’s, who is writing a book about this whole affair and interviewed the boy. It wasn’t his lover at all, it was a pickup. There’s no reason to believe there was anything pleasurable or masochistic about it. This boy hit him over the head. That was something he didn’t expect at all. The boy was a hit man. Pasolini had had experience with lots of boys like that. Pasolini was a black belt karate, he could have handled that kid with one hand, but he didn’t have a chance. The kid hit him over the head from behind. The kid claimed that he was horrified by the sexual demands of Pasolini. That is absolute rubbish. The boy’s story did not stand up. He got life. Indeed, he is still in jail. He’s been in there for some years. So this guy that I met was writing a book about it. He had inside information; he had interviewed the boy and the lawyers and everybody connected with the case.

RICHARD HELL: Pasolini was dangerous to the right wing?

BURROUGHS: I know nothing about Italian politics, but apparently there were people who had reason to believe that and wanted him killed.

BOCKRIS: Legs, do you enjoy having dinner with Bill?

LEGS MCNEIL: He’s a lot of fun at parties and a heck of a nice guy, but I like the dinners Bill gives inside the Bunker best. They always have a little quiet desperation about them.…

WARHOL: Who do you think has a good walk?

BURROUGHS: I’ve got a pretty good walk. One foot goes right straight after the other. They don’t turn out. Tomorrow I’m leaving to talk on the unconscious at an international conference of psychoanalysts in Milan. I’m saying there isn’t an unconscious. I’m going to talk about the fact that although Freud was one of the first to observe some of the psychological damage caused by the capitalist ethic and the whole industrial revolution, he never got beyond this ethic himself, being an academic. While he saw the importance of lateral thinking he never thought it could be used constructively. The unconscious was a hell of a lot more unconscious in his day than it is now. In the nineteenth century sex was unmentionable and in consequence it became unthinkable to many people. The unconscious, then, is not a fixed entity, but varies from person to person, culture to culture, and epoch to epoch. I will suggest that the unconscious may be physiologically located in the nondominant brain hemisphere and cite Julian Jaynes. Freud saw the unconscious as undesirable and formulated the aim of therapy: “Where Id was there shall Ego be.” Julian Jaynes stresses the importance of the nondominant brain hemisphere, which performs a number of useful—in fact essential—functions, among which are space perception. If the right brain hemisphere is damaged in an accident the simplest space problem becomes very difficult. So it isn’t a question of territorial war, but rather of trying to harmonize the two brain hemispheres. I’m announcing it at the conference as something called “hemispheric therapy.”

BOCKRIS: And what exactly is that?

BURROUGHS: Harmonizing the two brain hemispheres. Instead of being in conflict they are complementing each other. If you get rid of your unconscious, your whole right brain hemisphere, as happens sometimes in accidents, you’re terribly handicapped. There are all sorts of things you can’t do. For example [draws on a paper napkin a series of O’s and X’s] it would be very difficult to say which was the next one in sequence if your right brain was damaged. You wouldn’t know.

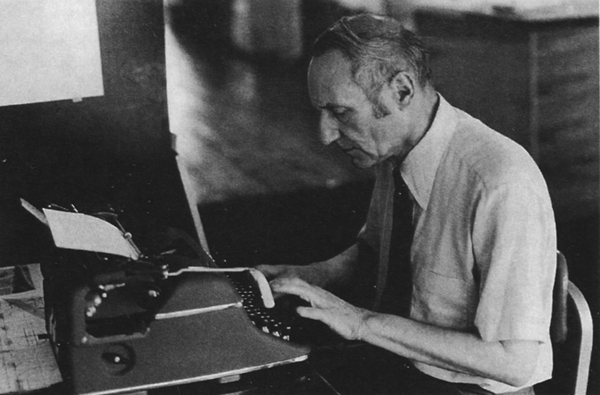

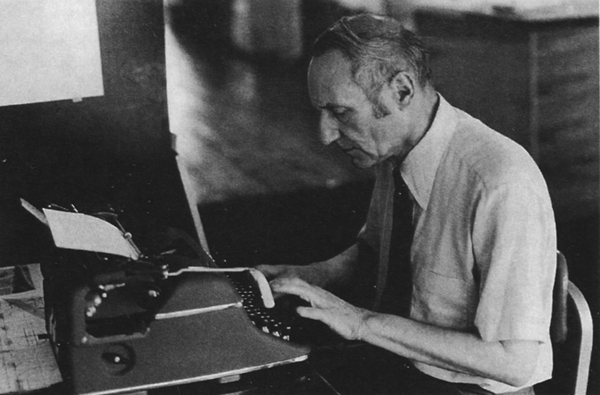

William Burroughs writing Cities of the Red Night, the Bunker, New York City, 1977. Photo: Gerard Malanga

BOCKRIS: Were you invited to speak about whatever you wanted to speak about?

BURROUGHS: No. The whole conference is on this subject, they wanted me to speak to it. They asked me: “Have you got something to say or read?” I answered yes. So they said, “Oh, but we thought you said you never read Freud.” “On the contrary,” I told them, “I have read practically everything that Freud ever wrote.” About twelve volumes. So I’m very well acquainted with this whole theory.

BOCKRIS: When did you read Freud?

BURROUGHS: About thirty-five, forty years ago.

BOCKRIS: What was your reaction to it when you read it?

BURROUGHS: It’s obvious that the whole thing is riddled with errors and a lot of these errors are inseparable from the social configuration. For example, hysteria has almost ceased to exist as such. This is when someone faced with difficult circumstances, say like taking an examination, becomes quite genuinely sick. He doesn’t know what he’s doing, and he doesn’t realize that he’s doing it to himself; if he did he wouldn’t be able to do it. Hysterics produce quite genuine symptoms. This illness called hysteria was common in Freud’s day, whereas it’s rare at the present time, or confined to backward places like Ireland and Portugal. Take hysterical paralysis: people are paralyzed for long periods and it’s simply hysteria. You just have to say the right words or get them to say the right words and bingo they’re cured, like people cured of paralysis at Lourdes. They were suffering from hysterical paralysis so they get up out of their wheelchairs and walk, but they were never organically paralyzed to begin with.

BOCKRIS: Is this a scientific conference? What kind of people are they inviting?

BURROUGHS: Psychoanalysts. It’s a psychoanalysts convention, but I don’t think I will be the only nonpsychoanalyst there. There’ll be people from all over the place, mostly Europeans, and a lot of them, oddly enough, are Marxists.

BOCKRIS: That’s not so odd for Italy is it?

BURROUGHS: It’s not odd for Italy, but I don’t see any connection between psychoanalysis and Marxism.

BOCKRIS: Freud better look out for his rep!

BURROUGHS: Oh well, his reputation’s been bandied around a great deal and he is now being increasingly seen in more perspective as an innovator and a pioneer. He was a therapist. His patients were middle-class nineteenth-century Viennese. It’s hard for us to imagine the extent to which sexual subjects were taboo and unmentionable. This is back in the nineteenth century, and I think he had more women patients than men. Many of his female patients had symptoms that were obviously the result of sexual repression. I’m going to cite Julian Jaynes, Dunne’s Experiment with Time, and Korzybski’s General Semantics. I am skeptical of the whole concept of “mental illness.” Wherever there is “mental illness” there is physical illness. I had a cousin; at the age of thirty-eight he was a square citizen, started having these bizarre hallucinations—his leg was on fire, all kinds of things like that so the doctors gave him a neurological once-over, very sloppy as it turns out, and said there was no sign of organic illness, therefore he had a psychosis, right, schizophrenia. So they were analyzing him on the couch and in the course of this he died of a brain tumor. Well, that was sloppiness on their part. I would have said, if you don’t turn something up keep looking, because there’s something there. There’s no reason for a square stockbroker at the age of thirty-eight to suddenly exhibit these symptoms. And they were saying, “Why would he be thinking all this?” and looking for childhood traumas. He was vomiting and they said, “Oh, this is a psychosomatic symptom.” The next thing you know he was dead of a brain tumor.

BOCKRIS: Was there a particular point at which you turned away from this psychiatric approach?

BURROUGHS: It’s not a specific approach; there was just a particular point when more evidence turned up relating to precise brain areas. I think analysis is a very antiquated approach. In fact, I’ve seen people who’ve been in psychoanalysis for five years and weren’t getting any better, and I said this is a bunch of shit.

BILL’S 66th BIRTHDAY DINNER AT THE BUNKER, FEBRUARY 5, 1980

BURROUGHS: I just got back from Milan. The guy who organized it, Professor Verdiglione, is a lay analyst. Verdiglione is a practicing psychoanalyst; he has his own publishing company, with branches in France and Italy, and he’s written a number of books on language and the unconscious, a small fat man, but with great authority. This convention is the third one he’s organized. He’d gotten a big building around a courtyard called the Palace of the Orphans, which used to be an orphanage back in the Middle Ages and was now being used to house the participants. The rooms were reasonable, small but with a bath. He says to me in the afternoon, “Mr. Burroughs, so and so is giving a talk in ten minutes. You will be on the platform.” It’s not an invitation, it’s an order. I said, “Well, I have to go up to my room.” He said, “You are coming back.” Anyway, I gave my talk on Freud and the unconscious at nine o’clock in the morning the day after I arrived. They were trying to translate it into both French and Italian because a lot of people there were French, and at this rate it would have taken the rest of the day. So Verdiglione said, “Let Burroughs read it in English and then you give a summary.” They did. It was impossible to tell if anyone understood anything I said or not. Then I was drafted to be on the platform with this other guy, a Frenchman named Alain Fournier, whose talk had nothing to do with the unconscious; he was just going on about the rape of Cambodia, the invasion of Afghanistan, in other words the non-Communist left, Mary McCarthy’s camp. He was calling for a boycott on the Olympic Games. I was sitting there all this time and people were taking pictures. Then there was a big lead in the newspapers the following day: THE UNCONSCIOUS SAYS NO TO MOSCOW.

BOCKRIS: For the rest of the conference did you listen to everybody else’s talks?

BURROUGHS: There’s no point, I can’t understand it, it’s all in French and Italian.

BOCKRIS: What do you think his interest in you was?

BURROUGHS: PR obviously. He wants as many “name” people as possible at his conference. The more such people he gets, the more important the conference is. Anyway, in the afternoon I was supposed to take part in a roundtable discussion including questions and answers with the audience in all languages. This started at 2:30 and I had some appointments to do interviews about 4:00. At 4:30 I said, “Well, I’ve got to see these journalists,” so I left the platform. Meanwhile, the roundtable went on until seven.

BOCKRIS: Is Italy very tense politically?

BURROUGHS: I felt no tension.

BOCKRIS: Did you get much of an impression of Milan?

BURROUGHS: Nothing. Pretty blank. I saw the Cathedral and the famous Gallery. The weather was cold and rainy.

BOCKRIS: What did you do in the evenings?

BURROUGHS: The first evening I had dinner with Verdiglione, the second evening I had dinner with Sr. Pini, the third evening I sulked in my room. This was the evening after I missed my plane. I went down and got a sandwich at the bar and went back up to my room and read a mystery story. And the next day I just got up and said goodbye.

BOCKRIS: Did people come up to you and respond; did anyone say anything about it?

BURROUGHS: Some Englishman who understood it got up and said it was an interesting talk, but he had some questions he wanted to ask and I never understood his questions; he went on and on. People who get up and want to ask questions want to make a statement. You see it doesn’t matter at all. The thing is that Mr. Burroughs is there and they will probably publish something in the paper. The press was there and took a lot of pictures, that’s it. It wasn’t a question of anyone understanding what I was saying. This kind of conference is like nothing I’ve ever seen before because it’s not a conference. I thought a psychoanalytic conference would be actual psychoanalysts, most of them would be medical doctors, and fifty or sixty of them. Instead, I find most of them aren’t psychoanalysts at all, or aren’t there to talk about psychoanalysis, and there are three or four hundred people milling around, some of whom have paid to attend the lectures. It’s unlike anything else I’ve ever seen, but they have such things in America. Steven Lowe’s father belongs to the Order of the Flying Morticians and they have conferences, so there’s nothing phony about it, it’s just cultural analysis created out of nowhere, using psychoanalysis as a springboard …