DINNER AT JOHN GIORNO’S: NEW YEARS EVE 1979–1980

BOCKRIS: Which is your nearest supermarket?

BURROUGHS: The Pioneer. It’s sloppy and it’s dirty and there are all these old biddies with their baskets and their cigarettes all in the corner of their mouths jamming the aisles and hovering around, but it’s the only supermarket within twenty blocks. You meet all sorts of people there. I meet Mike Goldberg, John Giorno and various people from the neighborhood at the check-out desk. Once I saw this young man with a beard and our eyes met and I said, “Well, how do you do?” And he said, “I know you but you don’t know me,” and I said, “Well, happy New Year.” I know all the cashiers. If they’re feeling really good, if it’s a really jolly day, they might say thank you. But it’s a great day if you can elicit a thank you out of the clerks at the Pioneer. It’s just that they don’t care. To a customer in Boulder it’s unthinkable that a clerk wouldn’t say, “Hi there! Hi there! Hi there!” and then go on to “Thank you. Come again. Happy New Year! Have a good day!” But this doesn’t happen at the Pioneer in New York. It does happen, though, in the drugstore. I’m well known in the drugstore. I go in there and gab with the pharmacist, who’s a gabby old guy anyway. Buying vitamins and talking about his experience with vitamins. They’ve got their own special vitamin pill, which contains everything that you need. “If you take one like this,” he says, “it’s like a drop in the rain bucket every day, and it can head off an awful lot because there are all these things you need you’re not getting. Things like zinc.” Are you getting enough zinc? Horrible results of zinc deficiency. All your teeth fall out for starters. So, it’s on that basis. They always have anything I want. I wanted to buy a special kind of glue. You wouldn’t think you’d buy it in a drugstore, but they had it: Duco cement. They have a special kind of ball-point pen that only costs 59 cents, the only kind I use; they have stationery; it’s one of those drugstores that does everything. And his wife is very much of a theatrical Spanish Dolores type, fairly good looking, a middle-aged woman who’s had a lot of sorrow but has great dignity and a great presence. She says, “Oh, why didn’t you say the usual, Mr. Burroughs?” Her husband was much older than she was. He was the one who told me that vitamin E gave him diarrhea. He died shortly after that and I never saw him again. But then she, who I presume was his wife, was around with the armband for a while, and she also has either a daughter or sister who looks like her but is not young enough to be her child, sort of a heavy-set woman with a mustache. It’s a whole family. A new pharmacist appeared and what the relation between him and her is at this point I don’t know. He knows everyone in the neighborhood. For example he’ll advise someone: “You need glasses. You’re entitled to them on your social security.” He’s always instructing someone, telling them to do this or that. “I can give you this and charge you more for it, but I can give you the same product and charge you less.” It’s also a news exchange. There’d been a mugging and there was a report. Some woman got beaten up and she’s at the counter and they’re all commiserating and saying “two black boys.” And the Patrone, grandiose and sad in a Latin way, experienced woman said, “Yes, those are the ones, those are the ones …” She’s got quite a lot of style; she’s a real actress in the classical manner, still beautiful and still sort of trembling on the verge.… There’s a whole French novel right there on The Last Adventure: She gets taken by some Puerto Rican boy and the old pharmacist, mad with jealousy, comes in and kills them both. He’s an old character, that guy.

DINNER WITH PETER BEARD AND BOCKRIS-WYLIE: NEW YORK 1976

BEARD: If I were a cabdriver I’d have a weapon for sure.

BURROUGHS: Personally it would give me a great feeling if faced by muggers to pull out a gun on them.

BEARD: I’d like to blast them.

BURROUGHS: I don’t mean shoot them. I’d give them a chance. I’d say: “You better get out of here quick.”

BOCKRIS-WYLIE: I love that story you told about the guy on the Bowery who said he had a gun in his pocket …

BEARD: You never know how many guys are just around the corner backing him up.

BURROUGHS: He didn’t have fuckall backing him up, he was just all alone there trying to get smart.

BOCKRIS-WYLIE: Do you think you’d be good in a situation defending yourself?

BURROUGHS: I’ve always been good in those situations.

BOCKRIS-WYLIE: Has anyone ever tried to kill you?

BURROUGHS: People have attacked me. I beat the other person hands down. He’s causing me trouble, I said, “Don’t like ya and I don’t know ya and now my God I’m gonna show ya!” That’s from The Wild Party, written in 1922. On the few occasions in which I’ve been attacked physically I won hands down.

BOCKRIS-WYLIE: Do you think that’s because you want to stay alive more than the person who’s attacking you?

BURROUGHS: Exactly. It was like the original situation in the subway. This guy says, “Okay you guys, ya been in my pockets, we’re goin’ downtown.” And the Sailor hit him and he fell down, but he was still hanging on to the Sailor and the Sailor said, “Get this mooch offa me.” So I hit him once in the jaw and kicked him once in the ribs. The rib smashed. Because I hadda get outta that, man. I hadda get out of that situation.

BOCKRIS-WYLIE: Have you ever been really scared that you would die in a situation where you were attacked?

BURROUGHS: I can’t say that I have. There was a situation in Tangier where I was talking to some boys out in front of the house and this nutty shoeshine boy comes up and says, “You fuckin’ queer.” I said something, and he hit me across the face with his shoeshine box. So I pulled the old elbow on him. There’s no strength needed in fighting, no strength needed at all. Just threw an elbow across his face and brought it back and he ran away to a big lot and hit me with a stone.

BOCKRIS-WYLIE: What’d you do then?

BURROUGHS: Nothing, because he could run faster than I could. I remember one CIA man in Tangier who got in an altercation with a shoeshine boy. He slapped the shoeshine boy, the shoeshine boy grabbed a piece of glass and the CIA man kicked him in the nuts and the boy ran off screaming. He was the ugliest American of them all …

NIGHT OF THE WHITE PILLS

I got to the Bunker around 6:30. Howard was there also. We had drinks and a light, pleasant dinner which Bill cooked and served. I was still feeling pretty ropy from being ill and Bill seemed a bit out of it himself. We drank a bit too much. I’ve noticed recently that Bill isn’t getting drunk very often. But this night we continued to drink more vodka after dinner. I was telling Bill that I didn’t know what to do and he said, “Do nothing.” He said, “Most of these problems are very simple. People think they’re very complicated but they’re not—just do nothing.” He said, “If one man refuses to believe in all this crap, that liberates everyone from it.”

Howard produced a handful of small white pills which he said were Swedish and very good, suggesting we all take some.

“What are they?” Bill asked.

“I don’t know. I have no idea,” Howard replied, “but this friend gave them to me and said they were great.”

“I ain’t takin’ nothing if I don’t know what it is,” Bill said. “Why don’t you take some and we’ll see what happens to you?”

Howard agreed, and took two of the pills. When they’d been in his system for an hour and a half he was able to report that he felt quite good—“drowsy eyelids—maybe some kind of synthetic opiate.” Bill swallowed two of the pills. Half an hour later I noticed that there was only one pill left, so I took it. I remember looking at my watch. It was 11:30 and I said to myself, “You really ought to go.” I was supposed to be at the Mudd Club at 10:00. The next thing I remember is looking at my watch and it was 6:30 A.M., I was sitting straight up in the same chair I’d been sitting in so I presumed I hadn’t moved. William was standing over by the sink washing a saucepan. “Bill wha … what’s happening?” I stuttered. “What are you doing?”

“Oh, nothing,” he replied vaguely. “I’m just checking things out, seeing what’s going on.”

I asked Bill if I could stay over because, even though at the time I felt all right, I basically knew something was wrong, so I stayed over on intuition. I went into the bathroom and washed up. Bill showed me where the blankets for the spare bed were kept, made sure I had everything I needed, and we both went to bed around 7:00 A.M. I heard Bill moving around about noon. After a while he came in to see how I was. I was sick and couldn’t get out of bed. I asked him if it would be all right if I stayed in bed for the day. He said, “Of course” and basically left me alone between noon and 6:00. He made one attempt to entertain me when he came in to show me the handful of pellets he’d dug out of the phone book in the orgone box in the cupboard. I couldn’t make out what he was talking about. “Don’t you remember?” he said. “I was firing the air pistol off last night. Look, I’ll show you …” and he led me into the cupboard, opened up the orgone box, and there was a heavily peppered telephone book.

Around 4:00 in the afternoon someone who was writing a dissertation on him came by. At 6:00 Bill came in. “What you need is the hair of the dog.”

“What do you mean?”

“A drink,” he said. Funnily enough I really felt like one, so, getting up slowly, I dressed and we met again at the conference table twenty four hours after we’d originally sat down to cocktails the previous evening. “Everything’s back to normal,” I said.

“Yes, everything’s back to normal.” Bill gave me a vodka and tonic and said, “I’ll make you some Jewish penicillin.” I ate my chicken soup and went home to bed.

ALLEN GINSBERG TEARGASSED BY WILLIAM BURROUGHS

Miles was visiting New York. I called William up and suggested the three of us get together. We arranged a date. We arrived at Bill’s place almost exactly on the dot of 6:00, taking a pint of vodka and some extra tonic water with us. William seemed in fine fettle as he met us to unlock the gate. We went upstairs. Soon John Giorno joined us. We talked about the White Gorilla of which William had seen pictures in National Geographic. He remarked that National Geographic provided the perfect CIA front: “Well, our man has been in the area for twenty years and he knows all about it. Anything you need, ask our man.”

The facts about our night on white pills were beginning to come into focus. According to John, we had paid him a visit around 3:00 A.M. that night. I passed out into his lap every ten minutes, but John would always lift me back up, at which point I’d come to. William, on the other hand, talked loquaciously. Neither Bill nor I have any memory of this visit.

The phone rang. Knowing how much Bill dislikes talking on the telephone, I answered. It was Terry Southern calling to announce his imminent arrival in New York. It rang again. This time, it was Allen trying to get in. I went down to open the gates. It was while I was downstairs that, according to Miles, William put his teargas gun on the table and started explaining how it works. Miles’ girlfriend, Rosemary, said she didn’t believe it was as powerful as Bill claimed and, to make his point, Bill said, “Look, I’ll show you,” turned away from her and pointed it out into the room. “Careful, Bill, this is a closed space!” John shouted as William fired. By the time Allen and I came upstairs, John, Miles, Rosemary, and Bill were convulsed in coughing fits. At first Allen and I couldn’t tell what was going on, but then Allen said, “What is that?” and everybody tried to gurgle something out in between coughing and laughter. We heard: “Tear gas! Tear gas! Bill teargassed us!”

William had certainly made his point. We all went into the small room next door where Bill keeps his phones and files and found the air in there significantly clearer. Allen was slightly peeved: “Well, Bill doesn’t seem to be taking this very seriously.” William was trying to keep a straight face while being immensely amused as he ran around the Bunker waving a handkerchief in a feeble attempt to clear the air. It took an hour. When we finally sat down to dinner, William was still more amused than anybody else. “It’s so chic to be teargassed by William Burroughs just as you’re sitting down to be his guest for dinner,” I said to Allen, and he had to agree, chuckling over the incident for the first time now.

FRIDAY NIGHT

“Hello, old boy,” Bill murmured through the iron gates as I approached from across the street. “See, we got a new lock.”

“Why?” I asked.

“Somebody broke the old one.” As we walked upstairs I said, “It’s good of you to see me at such short notice.” I had just called an hour earlier.

“Not at all, not at all.” Bill was clearly spending the evening alone. When I went in there was a paperback on the table turned upside down and open about halfway through. He was making a small meal in a saucepan on the stove. He offered me some, although there was only enough for one. I declined on the grounds that I had a later dinner appointment.

We sat down. I started drinking vodka quickly. We had a very pleasant two hours together. William remembered a story that Robert Duncan had told him. Apparently one day Burroughs was supposed to be walking along the Seine with Beckett discussing the efficacy of random murder. Beckett questioned Burroughs’ points, upon which William pulled out a gun, whirled, and picked off a passing Paris clocharde. He disposed of the body in the Seine and Beckett was convinced. “I rather like to hear that kind of story,” William laughed, “and I do nothing at all to discourage them. In fact, the people who repeat these stories might find the same thing happening to themselves, you see,” and he slapped the table emphatically.

William told me that Gregory Corso broke the front door when it wouldn’t open at his command and that Mike Goldberg, who lives upstairs, was very upset and shouted at him. Burroughs agreed with Mike. “My reputation in the building has been affected by the event. It’s always like this with Gregory,” he complained. “Wherever he goes it’s always cops and everything. The last thing I want is cops coming around. These two policemen came up here and asked if they could come in and I said, ‘Well, no, I’m sorry, you haven’t got a warrant, but I will bring the people responsible to the door, you see.’ That’s when Gregory got into the screaming match with Mike Goldberg.”

I left a copy of my Birthday Book on Bill for Allen. “I advise you to have one beer and nurse it,” Bill said. Just as we reached the bottom of the stairs, Mike Goldberg and his wife were coming in. “Oh, thank you for the new door, Mr. Burroughs,” they said. Bill smiled politely. “I hope your reputation hasn’t suffered too much,” I whispered.

“Oh well, it’s not all that bad,” he muttered, sheepishly amused.

THE ORDER OF THE GREY GENTLEMEN

Dinner at John Giorno’s with William. There was Bill, sitting in a medieval wooden armchair, nursing a vodka and tonic in front of a low, round, Moroccan table. “Hello, my dear,” he said, extending a hand, smiling. John’s apartment is furnished in medieval Moroccan Moslem chic. A whole lamb was being roasted in his fireplace. It was the beginning of summer. William looked like Graham Greene in Panama.

This was the evening of the formation of the Order of the Grey Gentlemen. It was all Bill’s idea. “A bunch of chaps should meet at one chap’s apartment and have a drink and a joint and hit up some coke. Then they go out on a mugger hunt with two or three companions and just stand around subways.” He pointed out that the Grey Gentlemen would have to always be impeccably dressed and approach the matter in classical fashion. The Grey Gentlemen, for example, carry only canes and Mace.

“If you saw someone being molested,” William continued, “you’d just casually stroll over and laconically, but at the same time with an authoritative air, say, ‘My good woman, is this man bothering you?’ And then you take this mugger and give his arm a good twisting and that’d be a warning.” Bill got worked up at this point. He was snarling and strangling his napkin. “So that if you see a mugger a second time, see, it’s onto the tracks … And the Grey Gentlemen always leave their card.

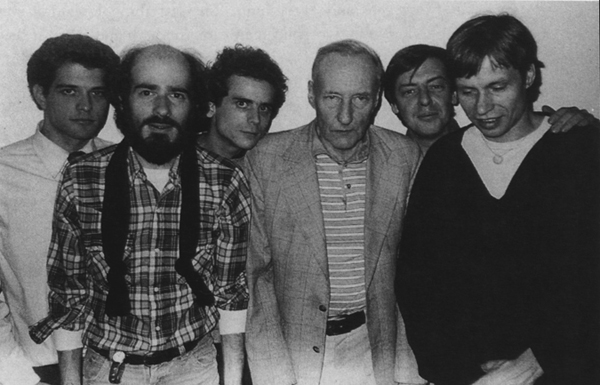

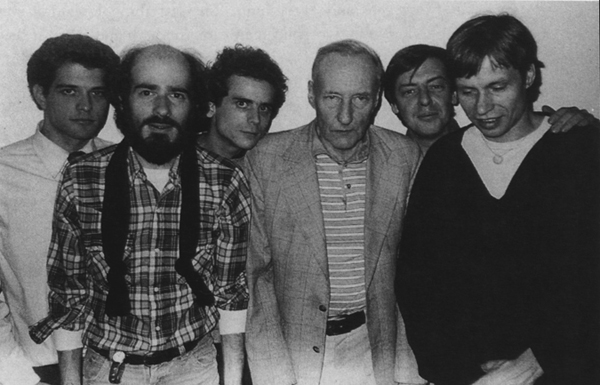

Brad Gooch, Stewart Meyer, Howard Brookner, Bill, David Prentice, Udo Breger at the Bunker on Bill’s sixty-sixth birthday. Photo: Victor Bockris

“Of course, they have a relationship with the Inspector. ‘Well, Burroughs, we can’t overlook too many more bodies, you know. Listen … this is the last time I’m warning you …’ and the Grey Gentlemen smile politely.…”

At one point during Bill’s detailed description of various raids that would happen, our relationship with the Red Berets, how the police would react, etc., I developed a scenario where we could rip off the jewels in Upper East Side restaurants. Burroughs leaped up and strode vigorously across the room.

“What we gonna do that for? We’re after muggers, man! You suddenly got us all set up as a gang of Raffles jewel thieves! This is an affront to the Grey Gentlemen!” And he whipped out his handkerchief as if it were a switchblade. John stepped between us. I humbly apologized, realizing my waywardness.

“Well, that’s all right, but watch your step,” Bill mumbled, fixing himself a short drink. Then we decided there’d be a showdown and one of the “Gentlemen” gets killed. This would be for the movie version. “Somebody may get killed but it’s not gonna be me,” said Bill, getting up and moving again.

“Well, Bill, it would make more sense to the audience if the older man got killed …”

“Nobody’s going to get killed! Why should anyone get killed? There’s not going to be any showdown! We’re just gonna go out on a mugger hunt …”

WINTER NIGHT

Since returning to New York William has gradually equipped himself with a small arsenal of weapons that includes a cane, a tube of teargas, which can be released in an assailant’s face by depression of a plunger and is particularly effective in subway situations, and a blackjack. “I never go out of the house without all three on me,” he says pointedly. “I don’t feel dressed without them.”

It was a bitterly cold, icy December night as I ran up the Bowery from the phone box on the corner of Canal Street to the gates of the Bunker where William was waiting concernedly.

“If I’d known it was like this I wouldn’t have asked you out,” were his first words as he opened the metal gates. He was wearing a jaunty tweed jacket, brown suede shoes, light brown pants, shirt, tie and sweater. “I went out today,” he said on the way upstairs. “It’s on days like this that you really [opening the front door and ushering me in] get to appreciate the Bunker. All the heat you can use.”

“I wouldn’t put a dog out on a day like this.”

“Well, I thought, ‘I’ll take my scarf I guess,’ but Jesus when I got out there!”

“Have you ever met Robbe-Grillet?”

“No. I saw one of his films.”

“Last Year at Marienbad?”

“No, it wasn’t Last Year at Marienbad, but it was very good, full of details of eating and things like that.”

“I wondered if you’d like to meet him.”

“Oh, well …” I could sense he wasn’t that interested.

“The thing is, I don’t know if Robbe-Grillet can speak English.”

“All the more reason for me not to meet him.”

“In that case there would be no point,” I agreed.

Bill looked up from where he was rolling a joint and said, “J’aime beaucoup votre livre, Moussieur.”

“Oui,” I said. “I will tell him. He is very pleased.”

“Yes. Tell him that I think he is a great artist and an excellent writer.”

“Out. Monsieur Burroughs dit que …”

“Yes, and then he whips out a book he purchased just ten minutes before our meeting and asks me to sign it, saying he has been a fan and read all my work for years. No, no, I really think such meetings are of little value.”

DINNER WITH FRED JORDAN: NEW YORK 1980

BURROUGHS: It’s a funny thing that’s never really been analyzed, the linguistic ability seems to be something special almost like a card sense that some people have and some just don’t have. I don’t have it at all, I just can’t learn a language.

FRED JORDAN: You’re lucky, because that makes you very strong in your native tongue.

BURROUGHS: Not at all. James Joyce was a brilliant linguist, my dear. Suddenly I’ve taken refuge with Shaw. I knew this guy who was a very good linguist with the CIA and he said in learning to speak Arabic he’d get this actual ache all through his throat and lungs, just like somebody riding who hasn’t sat on a horse in years. He had to use entirely different muscles. It comes easily to children. When I was in Mexico, shopkeepers would turn to my little kid who was four years old and say, “What did your father say?” And the boy would tell him in Spanish.

BACK AT THE BUNKER

I noticed a wrapped Christmas gift (unmistakably a cane) standing next to William’s cane by the wall. On a previous visit he had told me that he was planning to buy me a cane for Christmas and ascertained my height to make sure that it was the correct length. We returned to the conference table and continued talking. A few minutes later Bill said, “Victor, I have a Christmas present and I’m going to give it to you now. I don’t agree with all this waiting around for the exact day, it’s Christmas now, it’s a Christmas present,” and he walked into the bedroom.

I got up and walked to the middle of the room so that I would be in an advantageous position to formally receive my cane. When Bill came back into the living room he advanced and presented the cane sideways, like a sword on a pillow. I ripped the wrapping off, and saw that it was a replica of his cane. I started swinging it around and Bill launched into his new theory about the Caneraisers and how we were going to encourage a view of the cane as a weapon and see if we couldn’t get a commission from this shop he was dealing with if we started everyone buying canes. “See, it’s definitely a weapon that you are allowed to carry,” he pointed out. Then he went into the bedroom, got his cane, and we stood around brandishing canes and practicing cane maneuvers. At one point I got the handle of my cane stuck around the lower part of his leg at the moment that he got the handle of his cane stuck around the bottom of my leg, and we paused, embarrassed. “Oh … excuse me.”

“Bill, do you ever drink whiskey?”

“I used to, but I rather lost the taste for it.”

“When you were living in London?”

“Yes. I got a call today from someone at Rolling Stone records inviting me to Keith Richard’s birthday party tonight.”

“Let’s go!”

“I told them ‘Thank you very much, but I can’t make it.’”

“Bill! Why?”

“They said they’d send a car and everything to go somewhere out in the country. I thought it was very kind but I am very reclusive and not much of a partygoer.”

“Keith likes you very much …”

“I like him too.”

“Mick would be there. It’d be nice for you to see them again; it’s been a long time.”

“I know, but …” and he wandered off into the other room.

The next day Bill felt ill. He was ill for four days. I spoke with him on the phone daily. He did sound depressed. James called from Kansas, concerned about these depressions. “Bill has these feelings of being trapped in his body and not really wanting to be alive at all sometimes and I sympathize with him, but it’s no good him just sitting there and not doing anything.”

Burroughs does tend to withdraw into these periods where he will sit around the Bunker talking about going on mugger hunts and practicing with his various weapons. On the other hand he just called this afternoon to invite me over for dinner tomorrow with Allen and Peter and said he was going to Mickey’s tonight with Ted Morgan. Udo was going to drop by in the late afternoon, so he seems to be fairly active.

I took my friend Damita over for dinner on Monday, the 24th. She gave Bill a small cannon for Christmas and I gave him a St. Laurent shirt. Howard was there. We had a pleasant dinner. Bill’s liking Damita reflects a change from the problems Miles had when he took his girlfriends to dinner at Bill’s in the early seventies in London.

In fact, William seems in better shape than any time since I’ve known him. He’s flourishing in the afterglow of finishing Cities of the Red Night and continues to write essays, work on a new novel tentatively entitled The Place of Dead Roads, and prepare a series of European lectures and readings with vigor and confidence, still striding, as Kerouac had him, like an insane German philologist in exile.

DINNER WITH ALLEN GINSBERG: NEW YORK 1980

BURROUGHS: Did you read about those young scoundrels who terrorized a train? We must get our cane brigade organized.

BOCKRIS: Bill and I have organized a cane fighters group. Everyone has a cane like this and we’re going to go on the subways. Three or four of us in the evening.

GINSBERG: New York City, 1980—the Cane Brigade! On my block everyone is armed with a staff or cane.

BURROUGHS: These are great, terrifically effective weapons.

BOCKRIS: There are many things you can do.

BURROUGHS: I’m ordering a blackjack for you.

BOCKRIS: When did you start actually cooking for yourself?

BURROUGHS: When I came back to America. When I was in Europe it wasn’t necessary to cook because there were so many cheap restaurants. When I came back here it became obvious that eating out was absolutely ridiculous.

BOCKRIS: You turned to cooking in your sixties as a new art form.

BURROUGHS: A new form of saving money is what it amounted to.

BOCKRIS: Did you hear about the guy who got a weekend pass from the mental hospital and went straight home and killed his wife? He said it was God’s justice.

BURROUGHS: Whatever happened to God’s justice? I am convinced that God exists and God is one asshole.

BOCKRIS: If you were terminally ill in such a way that you couldn’t do anything about it, or caught in an impossible situation, would you take your own life?

BURROUGHS: The only rational reason for people to carry cyanide around is if they are agents and facing torture if captured. I don’t know how you suddenly find yourself in an impossible situation just walking around the streets that calls for cyanide. I mean the same way with terminal illness. It isn’t something that just leaps upon you. Sort of “Jesus! I don’t even have time to get my cyanide out!”

BOCKRIS: What is your position on suicide?

BURROUGHS: Suicide, according to the Dudjom, is very very bad karmically. Unless it’s an impossible situation. Naturally it’s logical to kill yourself to avoid torture, which is a much worse karmic situation because it could leave you crippled psychically, but committing suicide for no good reason seems to me a very very bad move. In the first place, if you were actually able, if you were in a position of mastery, you would be able to leave your body, you would be able to die at will, as some people do apparently. The master chooses when he will die. If you’re in that situation, fine, but if you’re not in that situation, by committing suicide you’re sure to make your situation worse.

LUNCH WITH THE TIME MACHINE

A European artist named Kowalski had called me through Timothy Baum and asked to arrange a meeting with William, to whom he wanted to show his time machine. He had discovered and invented a machine that can reverse the voice at the same moment it releases itself so that you hear yourself, through a set of headphones, talking backward and forward at the same time. He thought Burroughs would be interested. He was. We made an appointment to meet at the Ronald Feldman Gallery, East Sixty-third Street, at 12:30. When I arrived, William was already there in a three-piece suit and his green felt hat. We spent twenty minutes looking at, talking about, and playing with this machine which is constructed inside a small metal suitcase. The suitcase is plugged into two speakers and a microphone. You can speak into the microphone and over a set of headphones hear yourself talking forward in one ear and backward in another. If you think about it, it sounds impossible. To reverse sound is easy but how is it possible to hear your words reversed at the exact moment you speak them?

Timothy had invited us out to lunch. Although Bill had told me on the phone the previous day, “That’s very nice of him, but I don’t think I have time for lunch as well,” he now turned to me, in response to Timothy’s repeated invitation, and said, “Victor, what do you think? Shall we have a bite of lunch?” I, of course, agreed, and so we walked around the corner to a small Greek restaurant. We ordered some food and two bottles of retsina. William drank ice water. “This man is a priest. He will not touch alcohol,” Timothy explained to the waiter.

After lunch, we headed toward Books & Company. As we strode up Madison Avenue I asked Bill about a puzzling sexual dream I’d had a few nights before.

“Yes, this is well known,” he said. “This is a visit by the succubus. Of course, you know about it.”

“I don’t know anything at all about that. Please tell me.”

“What! You don’t know about the succubus and incubus? My dear, this is well-known endemic folklore—household words in medieval times, I fancy.”

“Yes, but what is it?”

“The Demon Lover, my dear! The one who descends upon you!” At that moment Timothy descended upon us and our conversation broke off. Before we got to the bookstore I had a chance to ask him one more question. “Does the person who comes have anything to do with sending themselves? Are they at all aware of it?”

“Not much solid evidence of this. People don’t like to talk about it, but it happens more frequently than one would suppose.”

“Has it happened to you?”

“Of course. Many times.”

He could give me no more information about it, nor leads. “The sources are scattered,” he said, “but I will give you one piece of advice: don’t let whoever is bothering you know about it, because they might feel they have some kind of power over you.”

BURROUGHS AT THE FACTORY

A week later, William and I arrived at Andy Warhol’s Studio, The Factory, at 6:00 P.M. A young man wearing a red shirt and blond mustache answered the door and we walked in. William immediately commented on how large the place was. A beautiful girl was slouching behind Ronnie’s desk. I crossed to the windows facing onto Union Square, took off my coat, and put my briefcase on the radiator. William followed, taking off his coat. I turned, took it from him, and placed it with his hat and cane on an art deco armchair in a grouping of art deco pieces. I walked into Vincent Fremont’s office and he was on the telephone. “I’m here with Mr. Burroughs,” I said.

“Who are you?” he asked. “Do I know you from somewhere?” I made a face and he said, “I’ll go and find Andy.”

“Could you turn the lights on in the conference room?”

“No, we’re cutting down on electricity.”

I motioned to Bill and he followed us into the conference room. “Ronnie’s got that music on loud again.”

“Ask him to turn it down,” I replied, thinking about my tape. Vincent went down the corridor. Bill and I looked through the bottles and he chose to stick with Smirnoff as opposed to trying Wyborowa, which I recommended. I ran back into the main office to get my tape recorder and came back as William was pouring some vodka into a glass. Andy entered. He was wearing an open-necked red, white, and yellow plaid shirt, jeans and cowboy boots, carrying a small Sony tape recorder, turned on, and a miniature 35 mm Minox with flash attachment.

WARHOL: Gee, you’re all alone.

BOCKRIS: Bill’s not alone. I’m with him.

WARHOL: Oh, you are. What do you think about people wearing earrings?

BURROUGHS: I don’t know. I guess it’s sort of their business, Andy. I don’t have any strong feelings about it one way or the other.

BOCKRIS: You never wore one yourself?

BURROUGHS: Oooohhh, good heavens no! It’s not my style.

BOCKRIS: You know, Bill never had long hair or a mustache or anything like that in his whole life.

BURROUGHS: I did try once to grow a mustache and it came out in all different colors and straggly; it didn’t work. It was all itchy. I hated it. I’ve got a barber down on Canal Street. They give me a straight cut like you see here. I don’t go in for McSweeney because there isn’t too much to be done with my hair anyway.

WARHOL: I have terrible spots, I … I … my skin …

BURROUGHS: Did you ever grow a beard?

WARHOL: No, my skin is so bad I have splotches all over it. I don’t know, nerves I guess.

BOCKRIS: We’re spreading this thing about all men should carry canes.

WARHOL: That’s a very good idea. I’m going to carry one. I used to carry a teargas gun. Taylor Mead gave me one, but you’re not allowed to carry it.

BURROUGHS: I don’t feel dressed without my teargas gun. I usually just carry the teargas and a cane.

WARHOL: What kind of cane?

BURROUGHS [showing him]: You see, there’re all sorts of things you can do with a cane. I sent away for a book on cane fighting. I plan to start a cane store. It’s an art, like fencing.

WARHOL: Listen, I’m going to get one, I think it’s great!

BURROUGHS: This one only cost $10 and it’s nice to walk with, I like the feeling.

WARHOL: It’s a good shape too. It’s fat enough; it feels sexy.

BURROUGHS: I also use it to quell dogs. In Boulder I used to carry this against dogs and one day I went out without my cane and by God if a dog didn’t bite me. But I would prefer one made of metal with iron piping inside a wooden case.

WARHOL [as we walk through The Factory looking at paintings]: You’re looking so good. Do you really take care of yourself?

BURROUGHS: Oh yes, I do. I have some special abdominal exercises that I do for five or ten minutes every day and it’s very effective indeed.

BOCKRIS: One of the biggest problems for writers is that they sit all day.

BURROUGHS: Basically, they have to do a certain amount of sitting in order to get anything done. [He spots a stuffed lion John Reinhold sent from Africa for Andy’s birthday.] Look at this lion! I had a friend who was killed by a lion in a nightclub. The lion was asleep in a cage and Terry went into the cage and threw a flashlight in the lion’s face and it leapt on him. He was DOA at the Reynosa, Mexico, Red Cross. He had a crushed chest, a broken neck, and a fractured skull. It just jumped on him and killed him. Can you imagine anyone waking up a sleeping lion with a flashlight? The Mexican waiter went into the cage and tried to get it off him with a chair and he couldn’t. The lion dragged Terry into a corner. At this point the bartender came vaulting over the bar with a .45 and he went in and killed the lion, but Terry was dead. It’s a funny thing. About a month before Terry annoyed that lion we were in Corpus Christi and we built Terry up as Tiger Terry, this punch-drunk fighter, and Terry goes into a spit and shuffle act. Yeah, Tiger Terry …