A PASSPORT FOR WILLIAM BURROUGHS INTRODUCTION

“As a child I wanted to be a writer because writers were rich and famous,” Burroughs begins. “They lounged around Singapore and Rangoon smoking opium in yellow pongee silk suits. They sniffed cocaine in Mayfair and they penetrated forbidden swamps with a faithful native boy and lived in the native quarter of Tangier smoking hashish and languidly caressing a pet gazelle.

“My first literary essay was called The Autobiography of a Wolf. People laughed and said: ‘You mean the biography of a wolf.’ No, I mean the autobiography of a wolf and still do. I was quite sure I wanted to be a writer when I was eight. There was something called Carl Cranbury in Egypt that never got off the ground.… Carl Cranbury frozen back there on yellow lined paper, his hand an inch from his blue steel automatic. In this set I also wrote westerns, gangster stories, and haunted houses. I was quite sure that I wanted to be a writer.”

Burroughs was born February 5, 1914. He spent his childhood in a solid, three-story brick house in St. Louis in what he later described as “a malignant matriarchal society.” He was the grandson of the inventor of the adding machine, and his parents, Mr. and Mrs. Mortimer Burroughs, were comfortable. “My father owned and ran a glass business.” He has one brother, Mortimer Burroughs, Jr. The family of four lived with their English governess, whose name was Mary Evans (she left quite suddenly for England when Bill was five) at 4664 Pershing Avenue until William was twelve. As a child his hair was blond.

“My mother’s character was enigmatic and complex. Sometimes old and knowing, mostly with a tremulous look of doom and sadness, she suffered from head and back aches, was extremely psychic, and was interested in magic. She had a dream one night that my brother Mort came to the door, his face covered with blood, and said, ‘Mother, we’ve had an accident.’ And at that very moment, Mort was in a car accident and suffered a few minor cuts. She had a very definite intuition about people—‘like an animal,’ she described it. And she would make flat judgments, warning my father of a business contact: ‘I think he’s crooked all over.’ She was not a lady of reserve and nineteenth-century refinements; she was clearly crippled by her Bible Belt upbringing, which had imposed an abhorrence of bodily functions. She was indeed a lady of great poise and charm, and ran a gift and art shop for many years and wrote a book on flower arranging for the Coca-Cola Company. She was a complete alien to the icy, remote strata of the serene, rich matrons she saw every day in the shop.… ‘We must get together,’ they would say, but they rarely did. She didn’t belong in the ‘in’ group. Neither did my father, who certainly had nothing to recommend him in the way of lineage. Son of an originally penniless bank clerk from Massachusetts—nobody knew where he came from or who he was.

“So the family was never in. This feeling I experienced from early childhood, of living in a world where I was not accepted, caused me to develop a number of displeasing characteristics. I was shy and awkward, and at the same time furtive and purposeful. An old St. Louis aristocrat with cold blue eyes chews his pipe … ‘I don’t want that boy in the house again. He looks like a sheep-killing dog.’ And a St. Louis matron said: ‘He is a walking corpse.’ No, I was not escaping my elitist upbringing through crime: I was not searching for an identity denied me by the Wasp elite, who have frequently let me know just where I stand.

“My earliest memories were colored by a nightmare fear. I was afraid to be alone, and afraid of the dark, and afraid to go to sleep because of dreams where a supernatural horror seemed always on the point of taking shape. I was afraid someday the dream would still be there when I woke up. I recall hearing a maid talk about opium and how smoking opium brings sweet dreams, and I said, ‘I will smoke opium when I grow up.’

“I was subject to hallucinations as a child. Once I woke up in the early-morning light and saw little men playing in a blockhouse I had made. I felt no fear, only a feeling of stillness and wonder. Another recurrent hallucination or nightmare concerned ‘animals in the wall,’ and started with the delirium of a strange undiagnosed fever that I had at the age of four or five.

“I was timid with other children and afraid of physical violence. One aggressive little lesbian would pull my hair whenever she saw me. I would like to shove her face in right now, but she fell off a horse and broke her neck years ago.”

When William was twelve, his parents decided to move to a house in the suburbs with five acres of ground on Price Road. “My parents decided to ‘get away from people.’ They bought a large house with grounds and woods and a fish pond where there were squirrels instead of rats. They lived there in a comfortable capsule, with a beautiful garden and cut off from contact with the life of the city.” He attended the John Burroughs (no relation) private high school. “I was not particularly good or bad at sports. I had a definite blind spot for anything mechanical. I never liked competitive games and avoided these whenever possible. I became, in fact, a chronic malingerer. I did like fishing, hunting, and hiking.” He also read Wilde, Anatole France, Baudelaire, and Gide.

At fifteen Bill was sent to Los Alamos Ranch School in New Mexico for his health. He had a bad sinus condition. “I formed a romantic attachment for one of the boys at Los Alamos and we spent time together bicycling, fishing, and exploring old quarries. I kept a diary about ‘our relationship.’ I was sixteen and I’d just read Dorian Gray … you can imagine. Even now I blush to remember the contents of that grimoire. It put me off writing for many years. During the Easter vacation of my second year I persuaded my family to let me stay in St. Louis, so my things were packed and sent to me from school and I used to turn cold thinking that maybe the boys were reading my diary out loud to each other. When the box finally arrived I pried it open and threw away everything until I found the diary and destroyed it forthwith, without even a glance at the appalling pages.”

At that time, Burroughs read the autobiography of a burglar, called You Can’t Win by Jack Black. “It sounded good to me compared with the dullness of a Midwest suburb where all contact with life was shut out.” He and his friend found an abandoned factory, broke all the windows, and stole one chisel. They were caught, and their fathers had to pay for the damages. “After that my friend packed me in because our relationship was endangering his standing with the group. I saw there was no compromise with the group, the others, and I found myself a good deal alone. I drifted into solo adventure. My criminal acts were gestures, unprofitable and for the most part unpunished. I would break into houses and walk around without taking anything.… Sometimes I would drive around in the country with a .22 rifle, shooting chickens. I made the roads unsafe with reckless driving until an accident, from which I emerged miraculously and portentously unscratched, scared me into normal caution.”

Burroughs went on to Harvard, living first at Adams House and then Claverly Hall. “I majored in English literature for lack of interest in any other subject. I hated the university and I hated the town it was in. Everything about the place was dead. The university was a fake English setup taken over by the graduates of fake English public schools. I was lonely. I knew no one and strangers were regarded with distaste by the closed corporation of the desirables. Nobody asked me to join a club at Harvard. They didn’t like the looks of me. And when I tried to join the OSS under Bill Donovan with a letter from my uncle, I encountered, as the deciding factor, a professor who was head of the house I was living in at Harvard, who particularly didn’t like the looks of me. And later when I tried to join the American Field Service, this snotty young English school tie says, ‘Oh, uh, by the way, Burroughs, what were your clubs at Harvard? No clubs?’ He goes all dim and gray like the room was full of fog. ‘And what was your house?’ I named an unfashionable house. ‘We’ll consider your application.…’

“And the physical exam when I applied for a Naval commission.… The doctor said flatly, ‘His feet are flat, his eyesight bad, and put down that he is a very poor physical specimen.’ He gave me a tough aside: ‘You may get your commission, if you can throw some weight around.’ Needless to say, I had no weight to throw around anywhere. I wanted some. And that is what brought me to dabble in crime.”

“The only possible thing to do is what one wants to do,” Burroughs wrote years later in a letter to Jack Kerouac, who planned to write a book called Secret Mullings About Bill. With William Burroughs could just as well have been called Secret Mullings About Bill Updated, if the title hadn’t been too Kerouackian to steal, because as I got to know him I found myself increasingly mulling over Bill’s thoughts and actions. At sixty-seven he has become the wise old wolf who escapes from a forest fire at the end of his first literary essay: The Autobiography of a Wolf. In the words of one of his young friends, Stewart Meyer, “I saw that William not only holds water, but when he doesn’t he changes. This guy is everything he pretends to be. In fact, he’s not pretending. Isn’t that rare among famous people?” In this sense Burroughs is revealingly similar to Muhammad Ali and Andy Warhol, two other stars I’ve written portraits of. All three are exactly what they appear to be. They are, as Burroughs says of Genet, “right there.” And they are willing to let others benefit from their experiences.

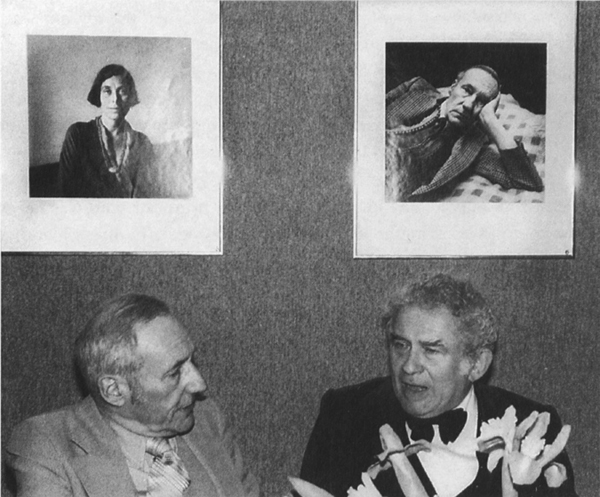

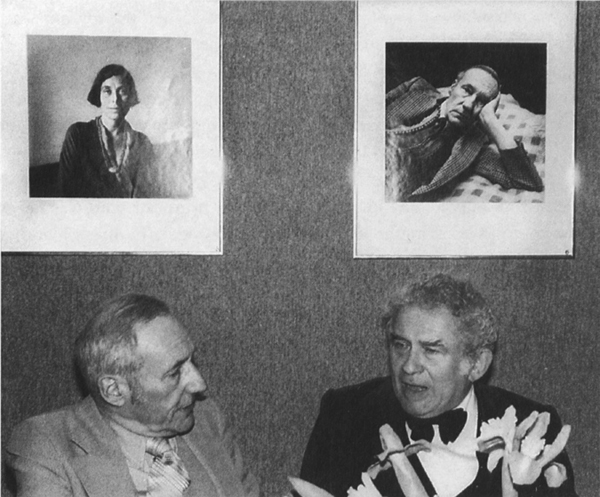

Burroughs and Mailer at dinner for Allen Ginsberg’s Gold Medal Award presentation at The Gramercy Arts Club. Note photo of Burroughs by Peter Hujar above Mailer’s head. Photo by Marcia Resnick

William Burroughs is, as Patti Smith has often pointed out, “the father of heavy metal,” who helped make the present possible by writing maps of territory that had previously been considered out of bounds. “It only takes one man to reject all this crap,” he states flatly, “and it can disappear for everybody.”

“Burroughs is a real man,” I heard Norman Mailer tell writer Legs McNeil.

“But … but,” Legs, an avid exponent of heterosexuality, spluttered.

“Oh no, that’s bullshit,” Norman insisted. “That is a man. I remember when we read the first sections of Naked Lunch we felt so relieved. We knew a great man had spoken.”

“Any writer who does not consider writing his only salvation, I—‘I trust him little in the commerce of the soul,’” says Burroughs.

The most difficult thing in a writer’s career is to keep on writing. The odds are very much against a writer’s being able to write to his satisfaction throughout his life. He has to keep traveling intuitively. He has to get off boats and planes to keep looking for new scenes he will need to write twenty years later. He may have to involve himself in other people’s dreams. He may have to spend weeks in bed with the covers pulled up over his head. Only by continual courage can this writer renew his essential writer’s passport. For, as Burroughs constantly reminds his students, “a writer must write.” Where Kerouac, who did not change, died at the hands of the writer in him, Burroughs found salvation in the vehicles writing gave him to continue traveling to Venus and other locations in.

The period With William Burroughs focuses on (1974–1980) has been extremely active, exciting and productive for Burroughs and constitutes a watermark in his career. He began the eighties by completing Cities of the Red Night, the novel that had occupied him since his return from London in ’74; beginning The Place of Dead Roads, his long awaited western; and looking for a piece of property on which, as he approaches his seventies, he plans to purchase or build a country house, where he will be able to chop wood, take walks, practice shooting his guns in between writing, and become a country gentleman.

Being a writer becomes largely a matter of character. It is the writer’s personality and attitudes that allow him to find a new way to go on, or stop him dead in his tracks. In With William Burroughs, I provide an introduction to the character of Burroughs through the mirror of these conversations with the characters who wander in and out of our pages. It is a portrait-in-the-round of a man whose writings and opinions have had great effect throughout the world of letters for the last twenty years, and whose work continues to be important to all those concerned with language and the question of survival. As he continues to travel it becomes evident that his writer’s passport will never be revoked. I hope this book may also stand as a celebration of William Burroughs.