Argauer

It’s easy to imagine Emma Argauer frantically searching the crowded deck of the Kaiserin Auguste Victoria as it steamed toward New York Harbor on a rainy Saturday morning in August of 1906. The family’s nine-day voyage from gritty Hamburg to a new start in America was nearing its end, and her six-year-old son had disappeared from sight.

“Artur? Wo bist du!” she cried out, with her other two other children by her side. Not that Emma was unaccustomed to such shenanigans.

Arthur Carl Maximilian Argauer had always found mischief, and that didn’t end on a ship full of wonders for him and his older siblings, Oscar and Ella. That said, they were crossing the ocean on the largest liner then in existence, no place for a little lost boy. Emma’s fright escalated by the second.

Suddenly, the chubby-legged kindchen appeared and embraced his mother’s leg. Her heart back in place, Emma let out a reproving sigh and wagged her finger.

“Du bist ein kleiner Teufel,” she gently scolded him, calling him a little devil, as he smiled back. She couldn’t be angry for long, certainly not at this moment. Instead, she palmed the boy’s face and extended her arm toward the remarkable scene off the bow. A shower had just cleared and the sun was shining on the distant Statue of Liberty, its copper just beginning to yield to a patina green. The fidgety youngster didn’t know it, but America, with all of its promise, awaited him. And few would exploit its vaunted potentialities as would Art Argauer: coach, educator, Renaissance Man—or as the headstone in East Ridgelawn Cemetery simply defines him—“humanitarian.”

Yet, when Argauer died in 1986, few realized he was a German immigrant. He’d become an institution in New Jersey and left a legacy that still endures at Tusculum College in Tennessee. And he did it through the most American of sports, football.

Arthur’s destiny was sealed when his father, Charles, decided to leave Germany. Charles graduated from the University of Stuttgart then studied fashion design in Paris, London and Berlin. The Argauers eventually settled in Rixdorf, near the perpetually disputed border with Denmark. Soon, though, Charles sensed the beginnings of Europe’s impending strife. Frictions over Morocco increased between Kaiser Wilhelm and French Premier Rouvier. Britain’s Royal Navy unveiled the H.M.S. Dreadnought, a battleship with an unprecedented array of big guns. Germany answered with plans to build two dreadnoughts and one battle cruiser per year. Charles Argauer responded by taking his family to America.

Charles, a respected tailor, had been intrigued by the country since a visit to San Francisco as a 15-year-old in 1888. He chose the East Coast, where he’d live among other expats in Carlstadt, New Jersey, known as that “pretty little German village on the hill.”

The Argauers weren’t typical turn-of-the-century immigrants. Charles was neither tired nor poor nor wretched, and the “huddled” masses meant nothing until his son coached football. Charles’ skill with needle, thread and tape measure well suited the numerous textile mills then populating the Passaic River. Furthermore, his excellent English (he also spoke French) was a distinct advantage for setting up a clothier business catering to affluent clients.

Carlstadt was a perfect choice as the family’s new home, not only because it was home to so many in his profession that it had at the time been known as “Tailor Town.” Perched above the New Jersey Meadowlands, where the area’s two NFL teams today share MetLife Stadium, Carlstadt made for an easy transition from Deutschland to Amerika.

Even its history was transcendent. In 1851, Dr. Carl Klein led the Freethinkers, a set of German socialists, in staking out the land for themselves. The old story is that Carl somehow managed to remain the town’s namesake, even after he had absconded with the treasury. Another story, however, is much kinder to the good doctor—one of a broken man leaving town after discovering his wife’s affair, and that it was she who fled with the funds. In any case, Klein supposedly rests (uneasily) in an unmarked grave in a Staten Island cemetery.

The Freethinkers were an industrious ilk that valued hard work and, above all, education. Yet, they thought little of religion. Oppressive clerics had chased them out of Germany. In the original articles of incorporation of the founding German Democratic Land Corporation, it was stipulated that no religious worship would be permitted within the village’s boundaries.

But as more devout Germans made Carlstadt their home, the German Evangelical Church (later the First Presbyterian) was built on aptly-named Division Street, with all houses of worship built only on one side of it. The Freethinkers barely tolerated the Evangelicals but downright disdained the Catholics, who built their church on the East Rutherford side of the border.

By the time the Argauers moved into their house on Fourth Street, religious denizens outnumbered the secular, although the town remained predominantly German. It was a pleasant town and soon took on the semblance of a suburb, with neatly kept homes lining dirt and, later, paved roads. A trolley ran down Hackensack Street, the main thoroughfare. Carlstadt was the first town in the county to install gas lamps for artificial street lighting.

Education remained a focus in Carlstadt, so Arthur received a solid one for the era. The teaching of both English and German was still mandatory in Carlstadt, and he excelled at both, as well as in his other classes. It was when school was out, however, that Art could best satisfy his curiosity.

The waterways of the Meadowlands were yet to be polluted by decades of indiscriminate dumping of hazardous waste by more than 100 companies (if not a few corpses by the region’s infamous criminal element).

The Meadowlands Art Argauer knew were more reminiscent of colonial times when white cedars afforded hiding places for pirates, when fish, turtles and crabs flourished in the wetlands. Art and his siblings, Oscar and Ella, lived a short walk from a view down acres of flat marshland meandering into the river, then dissolving into the horizon of Manhattan’s skyline. In an age when church steeples towered over most towns, the Argauer kids marveled at the construction of the soon-to-be 11-story Metropolitan Life Insurance Company Tower. They lived within a mile of the creek, their swimming hole. Art and his older brother, Oscar, hunted muskrats. They fished and crabbed and played fetch with their dog, which provided them all the protection they’d ever need—including from their father.

If discipline needed to be dispensed at the end of a strap, still a common remunerator for childhood sins in those days, the dog had to be locked up first, or he’d charge fiercely to their rescue. Often, it seemed, Arthur and the dog were partners in crime. Once, Arthur returned home from the creek with a basket of crabs, which he carelessly set in the sink, from which they made their escape. His mother’s blood-curdling screams summoned him from his room back to the kitchen, only to see the crabs scuttling all over the floor. The dog barked wildly and snapped at the trespassers, adding to the mayhem.

Arthur’s punishment was to eat his breakfast standing up the next morning. That hardly deterred his adventurous streak. A couple of weeks later, he returned home to show his mother an old tin can full of colorful snakes. Wriggling and writhing, they were taken back to their natural habitat by order of Emma Argauer.

As the family moved up the White Trolley line, the young Argauer attended grammar schools in Carlstadt, Rutherford, East Rutherford and Passaic. It seemed his entire life embraced new experiences. He’d try his hand at everything—from manual labor to gourmet cooking.

Though a good student, Argauer didn’t graduate elementary school. As World War I broke out, the 14-year-old dropped out of the eighth grade and, whether out of boredom or impatience, went to work. Certainly it wasn’t at the urging of his father, who had made the most of his educational opportunities in Europe. But there was no reasoning with his headstrong son, who was already growing from a stubby boy into a strapping young man.

Hard work added to his frame. In the days before weight training, it was the best way for athletes to develop strength. Think of Red Grange hauling ice back in Wheaton, Illinois. Argauer had already been earning money working on a farm on the weekends. He then became a carpenter’s helper, a steamfitter, and a laborer at Forstmann Woolens, where he likely had toiled beside many of his future players’ parents. He was a “roller” at Athenia Steel, then worked for a wholesale cleaner and dyer and, finally, in his father’s tailor shop. Just before the Armistice was signed, he joined the merchant marine, a naturalized U.S. citizen willing to join the fight against Germany.

By that time, his father was well established as the leading tailor in the recently incorporated city of Clifton. To own an Argauer-crafted suit of Fortsmann wool was a fashion statement. Argauer could have joined his father in the business after working in the shop for a couple of years. Eventually, it might have been renamed Argauer & Son, a fixture on 720 Main Avenue. But that would not happen.

Argauer had no intention of pursuing a high school education. Instead, it pursued him. Clifton High School fielded baseball, basketball and track teams for the 1920-21 school year. Students who played their football on the sandlots were denied requests to the Board of Education to fund a team were made. But, led by a red-haired kid named Milt Sutter, they tried again in the summer of 1921. Sutter circulated a petition that was signed by every boy in the school, and to add some gravitas to the effort, they enlisted a physical education teacher, Carlton V. Palmer, to present their proposal to the Board.

Palmer was “a very aggressive fellow” according to Sutter in a newspaper interview shortly before he died at age 95. Palmer offered to coach the team and wriggled $300 out of the Board for equipment and uniforms.1

The petition had worked, just not according to the students’ plans. Palmer had been an assistant coach under the innovative Dan McGugin at Vanderbilt, and he saw this as an opportunity to coach at the high school level. But Palmer would not be satisfied leading a rag-tag group of kids who’d never played organized football and who didn’t know a single wing from a turkey leg. Instead, he began to round up older players who had never attended or finished high school. As there was not an age restriction at the time, when the boys showed up for the first practice, they were thrown in with some men five years their senior.

“They were not in school,” Sutter said. “I don’t know what the arrangements were, but they came back to class and attended like everyone else. It got so that we kids who started this movement weren’t going to be allowed to play because of the players he picked up.”2

Palmer searched farms and in factories far and wide for the guys who would carry his team. He found 18-year-old Vince Chimenti, one of his backfield stars, in Brooklyn. Twenty-year-old Ray Bednarcik, another ball carrier, came out of the silk mill. Bulky 19-year-old William Ziegler, who’d become the bulwark of the offensive line at center, was working on the railroad. And then, one day, on Ziegler’s tip, Palmer walked into the Argauer tailor shop on 720 Main Avenue on the corner of Clifton Avenue. He didn’t want a suit. He wanted the tailor’s apprentice son, and, while he wanted him for Clifton High, it was a day that, in changing the course of Art Argauer’s life, forever changed the destiny of Garfield High School football.

Palmer chatted with Art about football but also argued the importance of earning a diploma. His pitch must have also impressed Charles Argauer, who knew the value of an education from his schooling in Europe.

Art Argauer never forgot that fateful day. He’d eventually follow Palmer to MacKenzie School in Monroe, New York, and then to Tusculum College in Tennessee. The same arguments that Palmer made to him, Argauer would use to assemble his football teams at Garfield.

For now, stronger and wiser than most of his classmates, he threw himself into athletics. By the end of his freshman year, he’d earn letters in four sports. His work in the mills put muscle on a frame that was built low to the ground, with thunderous thighs. The physique ideally suited him for both lugging the football and wearing the tools of ignorance as a catcher on the baseball team. Those thick legs could move, as well. In baseball, he stole 38 bases to set a state record. When he could, he’d hop on the bus with the track team to run sprints or throw the discus. He was the North Jersey champion in the 100-yard dash. Basketball was perhaps his weakest sport, although he’d end up coaching the sport and winning numerous titles at Garfield.

Sutter, the kid who got the football team started in the first place, did manage to earn a starting position at quarterback, which wasn’t the feature position it is today. Still, the quarterback called all the plays. With Argauer, Chimenti and Bednarcik in his backfield, he didn’t call his own number that often. It was literally men against boys when Clifton took the field. “Ziegler could block like nobody’s business,” Sutter said. “It really wasn’t fair. We were playing against 15- and 16-year-old kids with men.”3

That 1921 season opened as a curiosity at Doherty Oval, the baseball stadium that was home to the Doherty Silk Sox, run by the Doherty Silk Mill. City fathers gathered in their top hats, and a school band belted out “rage and dirges” to take up the time waiting for the late arrival of the Butler High School team bus.

“Old man Jupiter Pluvius tried hard to put a crimp in the festivities,” wrote the Passaic Daily Herald, noting how showers were dampening the occasion. But none of it bothered the anxious boys about to take the field for Clifton.4

Argauer would score the first touchdown in school history on a simple one-yard plunge behind Ziegler, who was nicknamed “Arbuckle” because his heft was reminiscent of the famous silent film actor of the era. When Butler completed its first forward pass of the day, Argauer was there to knock the receiver down cold. “This type of tackling,” the Daily Herald predicted, “bids well for the future.” The final whistle blew as darkness was falling just when a Clifton touchdown made the final score, 46-0.5

The next week, Clifton beat Emerson, 32-0. For the season, the Clifton Maroon and Gray outscored opponents, 215-46. The only loss in eight games was a forfeit against Pingry Prep, the feeder school for Princeton University. Palmer pulled his team off the field when it was losing, 20-7, because he didn’t think Clifton was getting a fair shake from the officials, but the Mustangs were getting a dose of their own medicine from the more experienced Pingry team. “Pingry outclassed us,” Sutter would say. “I swore they put soap on the uniforms.”6

If Argauer needed any example of how exciting this could all be, it came in the fifth game of the season when Clifton, the small town, upset Hackensack, the big city, 21-14. That night, Palmer hired a brass band. What seemed like the entire student population did a snake dance down Main Avenue, past the Argauer tailor shop, and then on to the high school, where it lit a bonfire.7

“Take an old-fashioned country fair, and magnify it by 100,” a passage in the Clifton High yearbook describes. “Add the noise of an old-fashioned Fourth of July with the colors of a three-ringed circus, and more excitement than a Wall Street explosion. This will give you a plain idea of the night after the Hackensack football game.”8

Palmer moved on after that season to do relief work in Poland, but Clifton was just as formidable in 1922 under Clifford Hurlburt, who’d come down from Springfield, Massachusetts. While perennial power Rutherford was awarded the Class A state championship, Clifton put together an undefeated season as Argauer bid for All State honors. Clifton finished the season 9-0 by outscoring opponents, 140-31, including a 63-0 destruction of Hempstead, Long Island, led by Argauer’s four touchdowns, and a 21-2 win over a highly regarded New Brunswick team late in the season, which was regarded as a claim on the state title.

“Whirlwind smashes through the outside of tackle which have characterized practically all of Clifton’s earlier victories this year again paved the way to success,” Michael Shershin of the Daily Herald observed with awe. “With astounding speed and behind a wall of human flesh consisting of some five or six interferes, Captain Quinlan tore across the New Brunswick flanks time and time again. Then, when New Brunswick began to check this attack, Ray Bednarcik, the sturdy, hard running quarterback and Chimenti or Argauer, quite something of battering rams, diverted the drive to New Brunswick’s midsection with devastating destruction.”9

Art Argauer in his Clifton football uniform.

Passaic Daily Herald.

The final two games of the ’22 season had to have left a lasting impression on Argauer, each in its own way. Fresh off the win in New Brunswick, Clifton traveled to Newark for a game against Orange, where it slogged through not only a muddy field obscuring the chalk lines but also some questionable officiating, according to some accounts. Only two penalties were called against Orange by the referee identified as Schneider, even as several Clifton players, including Chimenti, had been knocked out of the fray.

Trailing, 13-12, late in the game, Argauer intercepted a pass at the Clifton 20, got ahead of the entire Orange team and was well on his way to an 80-yard go-ahead touchdown. As he eyed the end zone, though, the referee was whistling the play dead. Argauer stopped and turned around. Orange, the ref said, was offside on the play. Clifton, he said, could not decline the penalty.

Still, Clifton gained possession again, and was threatening at the Orange 20 with about 3:00 left in the game when Orange supporters spilled onto the field to demand Schneider end the game because of darkness. And that’s exactly what he did. Clifton apparently had lost its first game ever to a high school team.

Lesson about to be learned. If things appear to be out of your control on the field, control can be regained off the field, at least in those days. Clifton’s principal, Walter Nutt, protested the game that night and Walter Short, head of the state association, ruled it “No Game.”

Witnesses were called into a hearing. Schneider explained the confusion at the end of the game. He said he had heard someone tell him “Time up” when he was really being told “Time out,” so he picked up the ball and ran off to the field house. Such was the chaotic, often comic, state of high school sports at the time.

With its perfect record restored, Nutt sent a telegram to Short, making a claim on the Class A title and challenging any team in New Jersey to prove otherwise.10 When that challenge went unanswered, Hurlburt turned to his Massachusetts connections and set up a home-and-home series with undefeated state champion Norwood High. Norwood would come to Clifton first.

This would be Argauer’s first exposure to the thrill of intersectional play. Norwood was treated as royal visitors by the city of Clifton after arriving by steamer from Fall River to New York. The papers hyped the game all week. Clifton won the game, 13-10, with the Daily Herald describing Argauer as a “diamond under the light.” His touchdown run, which came early in the second quarter, was no ordinary play. In fact, it may have sowed the seed for the play that gave Garfield a 13-0 lead in Miami 17 years later, the Naked Reverse where Walter Young sprang John Grembowitz.

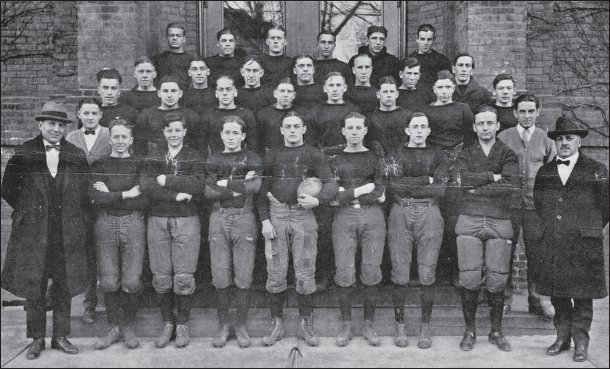

The 1923 Clifton High football team. Art Argauer is holding the football in the front row.

Clifton High School.

From the Norwood 20, Argauer was to run a routine off tackle slant to the right side. But Norwood had shifted its defense in that direction, leaving Clifton unable to set up the double team and trap blocks that made that play the basis of any single-wing attack. Seeing that, Argauer reversed his field, hiding behind the mass of humanity along the line, and when he swung to the left side, he was fully undetected.

Recounted the Daily Herald: “The run was a complete surprise to everyone, especially to Argauer’s teammates who wondered where he had gone to. He crossed the line all by his lonesome.”11

Although it hadn’t been set up that way on the blackboard, it was a classic misdirection play. Argauer could see how running several off-tackle plays to that side had influenced Norwood’s defense. Deception had as much of a role as power in an effective offense, especially on scoring plays.

Not all of Argauer’s instructive memories came on the football field. He’d learn another hard lesson on the hardwood, where he played guard on the Clifton team that nearly upset Passaic High School’s Wonder Team. The coach of that team, Professor Ernest Blood, is in the Basketball Hall of Fame. His scholarly demeanor was partly offset by the pet bear cub he kept as a courtside mascot. His charges won renown across the nation for a winning streak that reached a still-standing record 159 over five seasons before Hackensack ended it on a sawdust-strewn court in February, 1925—after Blood had left the school.

The streak could very well have ended two seasons earlier when Passaic escaped with a 36-34 win over Clifton in a game expected to be so lopsided that only a gaggle of spectators showed up to watch at the Paterson Armory. Passaic had beaten Englewood, 133-18, and Ocean City, 109-16 earlier that season and, three weeks earlier, chalked up win No. 103 over Clifton, 67-29.

Passaic was missing two starters in the rematch but, after jumping out to a 21-4 lead, another win seemed assured. Then the tide turned.

According to Daily Herald writer George H. Greenfield, “Passaic’s morale was completely destroyed, crushed, and swept away by the onrushing Maroon and Gray cohorts of Coach (Harry) Collester. With visions of a possible victory over the far-famed Wonder Team before their eyes, they made shots they had never made before, played a floor game that they never dreamed themselves capable of, and, in general, proceeded to throw a monkey wrench into the Passaic machine.”12

Led by Joe Tarris and two of Argauer’s football teammates, Bednarcik and Chimenti, Clifton held a 34-33 lead with one minute left. Or was it really a minute? Stories persist that the time remaining was closer to 10 seconds, and that the timekeeper—from Passaic—had a slow hand on the clock. Bednarcik missed a layup that would have iced it, and, just before the final whistle sounded, Passaic’s Mike Hamas made a basket and a free throw to keep the Wonder Team’s streak alive.13

Argauer would always contend that Clifton “was robbed.”

Elected captain of the 1923 football team, Argauer’s leadership skills were fast emerging. “Only a man of Argauer’s playing ability and caliber could endeavor such a task,” the Clifton paper crowed. Mighty Rutherford was Clifton’s first opponent that year and that’s where Clifton’s unbeaten record against high school teams ended in front of a crowd of 3,500. Still, Argauer stood out in the 16-6 loss.

“Captain Argauer, Clifton’s sensational quarterback, again proved himself a remarkable player,” the Daily Herald said. “He consistently gained ground for Clifton and as a bulwark on defense, both in the line as well as in open field plays. He made more tackles than any two members of the Clifton team and proved the all-around star of the day.”14

The loss would be Argauer’s last at Clifton. The Mustangs, as they would be known, won the remainder of their games in 1923 before Carlton Palmer came back into his life.

Palmer was recruiting a team again, now as the head coach of the MacKenzie School, an all-boys prep school in bucolic Orange County, New York. Situated on Lake Walton, the school boasted of alumni in all the Ivy League schools and of a 40-acre ball field, both of which attracted Argauer.

By that time, Argaeur’s interests had extended beyond sports. He acted in the school play and was elected class president. The lure of working under his first mentor again sealed his decision. At MacKenzie, he would also join Clifton teammate Chimenti and Emil “Jerry” Bilas, a player from neighboring Garfield.

The Jersey guys provided MacKenzie with an undefeated season, including a win over Bordentown Military Academy played before 3,500 fans in Clifton. But, at 24, Argauer had finally used up his high school eligibility. By now set on becoming a teacher and coach, he spent the next year at the Savage School of Physical Education, which was eventually absorbed by New York University. There, he met a former Garfield High football player named Al Del Greco. Del Greco would go on to play influential roles during the course of Argauer’s coaching tenure at Garfield, but all off the field. Blessed with preternatural wit, he pursued journalism after Savage. By 1930, Del Greco was sports editor of the Bergen Evening Record. He’d often use his pen to needle his old classmate. He once revealed that Argauer wore dentures. Yet, he also came to Argaurer’s defense when merited. The writers all loved Argauer.

Fate intervened yet again for Argauer when Palmer left MacKenzie to take the head coach’s job at Tusculum College in 1926, just in time to re-recruit Argauer. Argauer starred for him in football, where he attracted some attention from major college scouts, but, by then, he was more interested in his long-term prospects as a coach and mentor.

A letter home from Palmer to the Clifton newspaper made clear where Argauer was heading.

“Art is doing fine in his studies and is proving an especially likeable teacher in physical training. He is making great strides in many ways. Dr. Rankin (dean of the school) told me the other day of how different Art is from so many of the other northern boys, that he is more interested in his studies, gets better grades and is more gentlemanly.”

Palmer, as a matter of fact, remained one of the biggest influences in Argauer’s life. He eventually left coaching to become a highly successful art broker in Atlanta. Here was a man who studied in American and European universities, traveled to 42 foreign countries, including a trek, by camel, across the Arabian Desert from Aleppo in Syria to Baghdad in Iraq and served with the Polish Army in the Russian campaign. Palmer studied music in Germany, coached athletics at Vanderbilt and Tusculum, taught at the University of Alabama and lectured on art throughout the United States. He was the Renaissance man Argauer modeled himself after. While Argauer remained in the coaching profession his entire life, he appreciated what life offered beyond athletics. He was more than a football coach in that respect. He was an educator.

In that letter to Clifton, Palmer added that Argauer was going to coach the Doak High School basketball team in his spare time and it was there that he won his first championship as a coach. Doak wanted him to remain in Tennessee, but Argauer, as usual, was on the move. He earned his bachelor’s and Masters degrees at Columbia University, where he first met coach Lou Little, his frequent sounding board. He began teaching at Montclair Academy in 1928 and, a year later, he landed at Hannah Penn Junior High School in York, Pennsylvania. Naturally, he coached the football team to its best record ever.

The timing was perfect. As Argauer was building his resume in Pennsylvania, the Garfield High School football team was destroying its coaches’ reputation in New Jersey.

Yarborough

There can be a no more apt senior citation than the one that appeared under the coy countenance of Jesse Hardin Yarborough in the 1926 edition of the Cestrian, the yearbook of Chester High School in South Carolina:

Mule

Football ’24, ’25, ’26; Track ’25; President Junior Class

Some things start small and grow big

Mule is noted for a great many things, being most noted for his ability to play football. He believes in having a good time and is a great lover of the more beautiful things of life (girls). You never see him worrying over anything for he says, “Worrying may spoil my good looks.”15

Those off-hand musings turned out to be eerily prescient. Jesse—pronounced “Jess”—was nothing if not tenacious. The Mule nickname stuck with him throughout his life. His homespun humor could be both disarming and caustic. As for starting small and growing big, Yarborough seemed destined to rise from his sleepy southern town to the bright lights of Miami, and then on as a mover and shaker in Florida.

The Yarborough family’s roots ran deep in the red-clay soil of South Carolina’s Piedmont region, and as far back as the Revolutionary War. Jesse’s Virginia-born great-great grandfather, William Yarborough, was awarded land for his service with the South Carolina troops arrayed against Lord Cornwallis during his “winter of discontent” before his surrender of British forces at Yorktown. William became a planter in what was called the Fairfield District, a rolling land of “pines, ponds and pastures,” whose fertile valleys were well suited for growing cotton and small grains. William’s son, Henry, had acquired up to 26 slaves by the time of his death in 1853, leaving several to his son, William Burns—Jesse’s grandfather—who marched off to war with Company F of the 12th South Carolina regiment, also known as Means Light Infantry. He was wounded at Second Manassas, surrendered at Appomattox, then happily reunited with his wife, Lizzie, and their six children, including Jesse’s father, James Henry Yarborough.

Through him, Jesse Yarborough received an eye-witness appreciation of what Southerners preferred to call the War of Northern Aggression. His father was a self-described “tousled-head, freckle-faced” boy of nine years when General William T. Sherman’s troops, madly intent on wreaking havoc on the birthplace of secession, crossed the Broad River at Freshley’s Ferry and reached the Yarborough plantation at Jenkinsville. James Henry’s memory of the event was clear when, in June of 1938, W.W. Dixon interviewed him for the Federal Writers Project of the Work Progress Administration.

As the Union Army moved up from Columbia through the Fairfield District it left behind a trail of smoke pluming from burning farm buildings. The area was rich with provisions, only to be raided and carted away by the advancing Yankees. James Henry recalled the Bluecoats as they “confiscated everything, such as corn, wheat, oats, peas, fodder, hay, and all smokehouse supplies.

“I fought like fury to retain about a pack of corn-on-the-cob that the Yankees’ horses had left in a trough unconsumed. I remember, too, how grief stricken I was when a Yankee soldier killed my little pet dog,” he went on. “He had a gun with a bayonet fixed on the muzzle. He began teasing me about the corn. The little dog ran between my legs and growled and barked at the soldiers whereupon with an oath the soldier unfeelingly ran the bayonet through the neck of the faithful little dog and killed him.”16

The father’s return, as welcome as it was, did little to improve the welfare of the family, which would grow to include two post-war children and suffer the death of an infant. James Henry described his father as “a lover of nature, stars, flowers, birds, and trees. He was full of sentiment and high ideals, but he was not very practical in looking after and increasing his substance of material things.”17

After graduating from Furman University, James Henry spent a year teaching in Leon, Texas. According to his daughter, Hattie, he then studied law and was admitted to the bar, before, Hattie said, “he decided he would rather save a man before he got in trouble than to try and save him from prison after he got in trouble.” So, he instead decided to attend the Baptist Seminary in Louisville, Kentucky, and then returned to settle in Chester County, just north of Fairfield, where he set out to preach.

In 1891, he married the daughter of one of his deacons, Lily Inez Harden, whose family was one of the most prominent in Chester County. Jesse was the seventh of their eight children, born in 1906. When James Henry retired from the active ministry in 1926, leaving it to “younger men,” he was elected probate judge of Chester County and ran unopposed until his death in 1944 to be succeeded by his daughter, Hattie, affectionately known as “Mrs. Hattie.” Together, they held the position for 40 years.

Between his roles as minister and judge, James Henry married hundreds of couples. He was the picture of a Southern gentleman, tall with a wisp of hair and a cotton-white beard. He was exceedingly proud of his children, and he’d later dote on his grandchildren, slipping them money at each visit. When he died, the Chester News eulogized that he “enjoyed the warm friendship of thousands of people” and that “his friendly disposition, his kindly words will cause hundreds to revere his name.”18

Similarly, when Hattie passed away in 1973, the same paper paid tribute to her as a grand old lady, “the type of woman who if she liked you, let everyone know it. If you did something she didn’t like, she didn’t mince words with you but would be straightforward, shooting from the hip. How many people have been there to bear the sting of one of her lectures? How many more people have been there to be flattered by the love and attention she gave so freely?”19

All of James Henry’s children earned college degrees: three boys from Clemson and five girls from Limestone College. All found success in life.

Jesse was the mischievous one. As the second youngest, he enjoyed a natural dispensation, which he would exploit. Always curious, one family story had it that he would wrap himself in a carpet to eavesdrop on adult conversations. “He was the ‘bad boy’ of the family, smoking behind the barn, always doing something crazy as a kid,” said his daughter Louise. “His sisters would give him a hard time but my dad was always the one that was very special and well-loved.”

Most of James Henry’s time was devoted to preaching when Jesse was young. The family lived on farms, at first in Front Lawn, about 20 miles east of Chester and then in Baton Rouge, about 13 miles west. They were typical of the area, with fields cleared of yellow pine, oak, hickory, elm and black gum trees. Chester itself was—and still is—a typical southern town. Up on “The Hill,” historical structures still tower over the town: a Confederate monument, erected in 1905, a Romanesque Revival city hall from 1890, a Greek revival bank from 1919 converted to a Masonic Temple in 1942, a city jail from 1914 and a country courthouse that dates back to 1852, all part of Jesse Yarborough’s youth.

The football team, known as the Red Cyclones, played its games at the Chester County Fairgrounds, and, while the Red Cyclones never won a championship, Mule was good enough to attract the attention of Clemson College, which was then an all-male agricultural and military school.

His older brother James majored in veterinary medicine at Clemson and eventually practiced in Miami. Jesse majored in agricultural chemistry, was elected president of the junior class and, while he excelled on the football field, he didn’t neglect his studies to the point where he had hard choices to make over what career path to pursue.

While at Clemson, Yarborough met perhaps the biggest influences of his life in football: coach Josh Cody. Everyone on campus called Cody “Big Man” during his four years at Clemson, which coincided with Yarborough’s time there. He stood 6-foot-2 and weighed over 230 pounds, monster dimensions for his playing days at Vanderbilt (1914-1916 and again in 1919 after a two-year stint as an Army lieutenant in World War I).

Cody held 13 varsity letters in football, basketball, baseball and track with the Commodores. However, it was in football where he most excelled, named to three All-America teams as a two-way tackle. Extremely athletic and nimble for his size, Cody occasionally played in the backfield and once dropkicked a 45-yard field goal. In his four years playing for coach Dan McGugin, Vandy scored 1,099 points in 35 games.

A teammate once said of him: “He would tell the running backs on which side of him to go, and you could depend on him to take out two men as needed. He was the best football player I’ve ever seen.”

Cody tutored Yarborough at his old position and got the best out of him. “Mule” was more of a horse than mule by his senior year, filling out to 190 pounds and sporting a full head of hair with an iron-jawed expression. There were nothing but superlatives for his play as he earned All State honors from the Greenville News, leading the Tigers to an 8-2 record, with the only losses coming against powerful Tennessee and Florida, with the sensational Clyde Crabtree, his future assistant coach, dominating the game. When Clemson opened with a victory over Wofford, the Greenville News called Yarborough Cody’s greatest lineman. Under the heading “Fierce Tiger” and below Yarborough’s mug shot, the paper boasted of Mule’s, “wonderful game,” and that, “his tackling was as fierce as anything ever seen on Riggs Field.”20 Clemson’s school paper, The Tiger, chimed in: “Mule Yarborough was the big gun of the day. This big tackle broke through the Terrier ranks many times during the four heated sessions of play and smeared the Wofford backs for loss before they could move it of their tracks. The Mule reinforced his bid for fame by his wariness in recovering two blocked punts, each of which resulted in a touchdown for the Tigers.”21

After Yarborough helped Clemson avoid an upset against the Citadel, the News crowed, “Mule Yarborough played one of the greatest games of his career. Mule seems to rise to high planes when he meets the Citadel for it was last year that he entered the hall of fame when he did so well against the Charleston Cadets. (He) should rate among the best tackles ever appearing in the South if he keeps up this present pace.”22

Against North Carolina State, Yarborough was alert enough to notice the football graze off a Wolfpack player who was attempting to down a punt. He scooped it up and went 30 yards for a touchdown, prompting the Greenville News to write: “Mule Yarborough, who has been a brilliant performer at tackle for the Tigers, got his chance for glory this afternoon. And he made the most of it.”23

“Yarborough was everywhere in the game,” observed The Tiger.24

The next week, he scored again when he returned his own punt block 30 yards in a 75-0 rout of Newberry as The Tiger waxed effusively: “Mule Yarborough again asserted his supremacy over the opposition by crashing through the defense on many occasions to bring the ball carrier down for big losses.”25

Even after Tennessee dumped Clemson, The Tiger praised him. “Yarborough turned in another great performance,” it noted.26

Yarborough’s and Cody’s Clemson careers ended after the Tigers defeated arch-rival Furman to win the South Carolina state championship. The day before that game, Cody accepted McGugin’s offer to join him as an assistant coach at Vanderbilt, with the assumption that he would eventually succeed the “old man” upon his retirement. Rumors of his departure had surfaced two years earlier, when the Clemson cadets took up a collection and bought him a Buick. Touched by the gesture, Cody decided to stay.

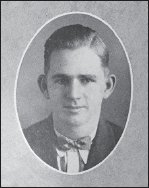

Jesse Yarborough at Clemson.

Greenville News.

Not this time. Yarborough reportedly gave a most heartfelt tribute to Cody at the post-season banquet. He and his coach remained close until Cody died of a heart attack in 1961. He looked up to Cody as a father figure and Cody considered him as a son. When Yarborough asked him for his recommendation when he applied for the Miami High School job in 1932, Cody replied (in the one letter Yarborough saved throughout his life): “I have just written (Principal) Mr. Thomas a strong letter of recommendation. There are some people whom it is hard for me to recommend. You are one whom it is always a pleasure to recommend. I really let out on you this time.”27

Later, during Cody’s years as head coach at the University of Florida, it was twice rumored he was bringing Yarborough on as an assistant, although it never progressed beyond that stage. Everyone knew how tight they were and how Yarborough modeled himself after his mentor.

Cody was widely hailed as a man of principle. He valued character, loyalty and respect. He treated his players as though they were his sons, yet never fully appreciated the influence a coach could have on players’ lives. In 1958, he demonstrated those principles as the athletic director of Temple University. The Owls’ basketball team, with three black players in its starting five, was scheduled to play an NCAA tournament game in segregated Charlotte. In a move not necessarily expected of a Tennessee-born farm boy, Cody made clear that if the players were separated by race, the team would not make the trip. The team stayed together and ended up third in the nation after a one-point semifinal loss to eventual champion Kentucky. Two weeks earlier, the Owls played a game at Wake Forest where their three black players were the first to ever play on the court. The game was not only played without incident, but, also, the three received a nice ovation during player introductions.

Yarborough’s style may have differed slightly but he was, just like Cody, exceedingly loyal to his players. “Honest and fearless with all the courage of his convictions,” Scoop Latimer of the Greenville News called him.28 And, before the game against Garfield in 1939, the Newark Evening News profiled him as a “hard driver but well liked.”

“Husky in stature and possessor of a somber, serious disposition, Coach Yarborough seldom cracks a smile when on the football field. Although he keeps his boys keyed to the proper pitch at all times, both physically and mentally, and does not tolerate any horseplay, he is idolized by his players,” the paper noted.29

Fresh out of Clemson, Yarborough considered a position at the Swift Company in Jacksonville before accepting the head coach’s job at Summerlin Institute in Bartow, Florida. There, in transforming a team that had won only two games the previous year to one that lost only three, the “great lover of the beautiful things of life” met the pretty daughter of General Albert Blanding. At 6-3, the imposing general stared eye-to-eye at Yarborough as he asked for Louise’s hand in marriage. Fort Blanding would be named after Yarborough’s esteemed father-in-law. Anyone from Florida who enlisted in the Army during World War II was initiated into the service there.

Yarborough, according to the Chester News, was about to resign at Summerlin and find a job in industry—a coach’s salary was hardly sufficient to support his new wife—when fate stepped in. Miami High School was in need of a football coach.30