Boilermakers

The freshmen trying out for football at Garfield High in 1936 were understandably nervous. Standing on the sidelines for the opening practice, many had struggled to even pull on their pads for the first time, never mind being thrown into the maelstrom of a full-fledged scrimmage. Now, wearing rag-tag uniforms with wide-eyed faces, they were about to be taken under the wing of Art Argauer. They knew, from both Argauer’s reputation and his stoic countenance that they were not going to be coddled.

Football, after all, was a natural pastime in Garfield. Kids were drawn to it. In an age where no one was handed anything and where a guy often had to “put up his dukes,” Argauer expected his players already hardened and ready to rumble. As one formed by the same mold, he would refine their rough edges with discipline and technique. But their inherent toughness would remain intact.

These freshmen gazed in wonder at Garfield’s three All State players: Jules Koshlap, Jim Schwartzinger and Steve Szot. Brawny, seasoned and mature, all three would go on to play for big-time college football programs. To the freshmen, they epitomized real football players, oozing self-confidence just by stretching, alone. But now, Argauer was calling one of the freshmen onto the field for an intrasquad scrimmage against these monsters.

Benny Babula was about to announce his presence.

Most everyone heard talk about a hotshot kid Argauer was bringing over from Clifton. But the varsity players figured he’d be just another freshman who would pass through what amounted to an initiation ritual: the first practice. They would welcome the green newcomers by showing them what life would be like on the suicide squad—the kids who, in effect, were sacrificed as tackling fodder. But Babula, they would soon understand, was not going to be pushed around for fun.

Argauer put Babula on kickoff coverage, tooted his whistle and eagerly eyed his prize recruit as he took off from the line. The kick sailed down the field and, with it, so did Babula, right under the chin of the unsuspecting receiver, knocking him dizzy. The varsity man lay flat on the ground blinking his eyes to clear his head. As the coaches tended to him, Koshlap and the others asked themselves, “Who is this kid?”

Bronislaw was his Christian name. Roughly translated from Polish it means “glorious defender.” In English, he was Benjamin, Benny to most, and simply Ben to his teammates. Over the next four years, most everyone around Garfield would know this name. If there were a Mount Rushmore of Garfield High School athletes, Babula’s would have been the first face chiseled into it. In later years, Boilermakers Wayne Chrebet, Luis Castillo and Miles Austin all had notable NFL careers, but none was as accomplished or as celebrated a high school player as Benny Babula.

Maybe Art Argauer couldn’t have foreseen that grand a high school career for Babula, even as his prized freshman smashed headlong into the upperclassman in that initial scrimmage. But Argauer certainly supposed he could be that sort of player to build a team around. Otherwise, he wouldn’t have recruited him from outside Garfield’s borders.

Yes. Arguably the school’s greatest football player ever came from Clifton. He was within sight of Garfield, surely, just a glance across the Passaic River near the Dundee Dam on Trimble Avenue. But Clifton High, where his brother and sister had studied, didn’t have a prayer of enrolling him once Art Argauer heard about the big bruiser. Even in his early youth, Babula had his way with the neighborhood kids in pick-up games on the dusty empty lots near his home. And so Argauer, himself a Clifton High legend, exploited a loophole to make Benny a Boilermaker.

It was a delicious coincidence that Babula’s mother, Tekla, came to the United States on the same vessel, the Kaiserin Auguste Victoria, that brought Argauer to America six years earlier. Benny had his mother’s features and his father’s drive. Shortly after arriving in New York in 1912, Michał Babula took a bride and opened a butcher shop in Passaic that he quickly converted into a wholesale meat distribution business. He ran the business out of Garfield and owned a couple of other Garfield properties to rent, including one on River Drive. That became Benny Babula’s “official” residence and, while it was sometimes questioned, it was never challenged—not even by Clifton High coach Al Lesko, who couldn’t have supplied Babula with as strong a supporting cast. Lesko no doubt swallowed hard and winced every time Garfield beat up his team.

In any case, Argauer wouldn’t have dwelled on it too much. Not all New Jersey towns had their own high schools. And those that did not typically sent their students to schools in neighboring towns. Lodi, for instance, sent kids to Garfield until it built its high school in 1931. Stanley Piela, later the Lodi football coach, was among the great Lodi athletes who played for Garfield in the 1920s. Wallington sent kids to Garfield, East Rutherford and Lodi at different times in the 1930s. Koshlop lived in Wallington. In 1937, the three Szot brothers, attended Garfield, East Rutherford and Lodi, respectively.

Babula started out playing tackle. That’s where he made his first varsity debut in a 67-0 rout of Port Jervis in the opening game of the ’36 season. It acclimated him to the Sturm und Drang of the trenches. But when Koshlap was hurt in the second game of the season, Argauer worked all week converting him to fullback. Over his high school career, Babula became a wonder, as good a triple-threat tailback as there was in high school football at the time. Flinging the ball with a three-quarter delivery, he could hit receivers far down the field. Some of his punts carried 60 yards in a day when field position was even more of a premium than in today’s game. But what Babula did best was run.

“He would carry two or three guys on his back and keep moving,” teammate Angelo Miranda said in a 1999 interview. “His legs were like pistons. I never saw anyone like him.”1

After Babula split time in the backfield with fellow All Stater Ted Ciesla on the 1938 state championship team, Argauer built the 1939 offense exclusively around Babula and dared opponents to stop the off-tackle smash. Behind precision blocking, Babula would roar around the end and lower his shoulder. Then the “fun” began for defenders. He was big—6-1, 194 pounds as a senior. But, because his legs kept churning, he was nearly impossible for a single player to restrain. He had the ability to cut sharply without losing momentum, but he was at his best as a north-south runner. He didn’t have breakaway speed, but he had huge strides that picked up yards in a flash. He owned a devastating stiff-arm and enviable balance to keep him on his feet.

“We knew where they were going to go and we’d move guys into those holes to stop him,” said Al Kacahadurian, who played against Garfield for Paterson Eastside High. “It didn’t matter. He ran over us anyway.”

Ernie Accorsi, the former general manager of the Giants, watched the film of the 1939 Garfield-Passaic game in which Babula rushed for 193 yards. His scouting report is filled with superlatives.

“What was amazing to me was that obviously Babula was going to carry the ball on virtually every play with very few reverses or much deception and they still couldn’t stop him,” Accorsi noted. “His explosive takeoff—he was at his top speed on the second step—and his powerful and quick strike force made it impossible for the defense to stop him at first contact.

“He was into the second level with suddenness and broke tackle after tackle, especially arm tackles. He almost always had to be gang tackled to get him down. When he did run wide he looked like the fastest player on the field, and I loved the way he would give the tackler a leg, then take it away or stop to make the tackler miss him then run by him.

“His vision, size, long strides, speed and most of all striking, lightning-like power basically made him unstoppable and, realizing he was essentially the sole target by the defense, made it all the more impressive. Despite the three quarter arm delivery common in those days (even Sammy Baugh delivered the ball in that manner) he threw the ball with accuracy. And how about his endurance? He did everything. What a player.”

Babula was the Golden Boy before there was Paul Hornung. He had the same dashing looks with wavy golden locks and a square jaw. When he returned an interception 90 yards for a touchdown in his senior year, Kachadurian, the quarterback who threw it, said his teammates were too much in awe to tackle him.

“Benny Babula scared the hell out of everybody. Even the name scared us,” Kachadurian said, remembering it all over 75 years later. “He was about 6-1, I guess, with broad shoulders. No facemask. You could see his features. And he was handsome, like Flash Gordon. I think we all stood aside and said, ‘Let him go, look how good he looks.’ ”

Babula knew it, too. He was supremely confident and impervious to pressure.

“Every time he was in a game, I was confident we would win it,” Miranda said. “All of our opponents knew it, too. But to us he was just Ben, the greatest teammate you could have.”

Babula, at least in high school, didn’t crave publicity. Although later in life, he would light up any room he walked into, his personality wasn’t yet made for the spotlight. His teammates liked to kid him about his naivety. Once, the players were handed an incomplete season schedule. Next to one of the weeks, it read, “Pending.”

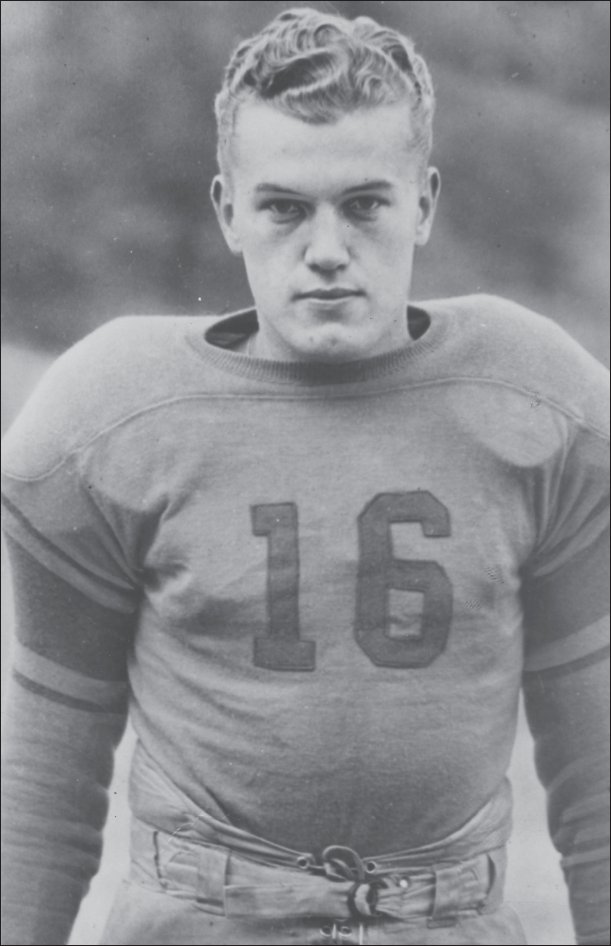

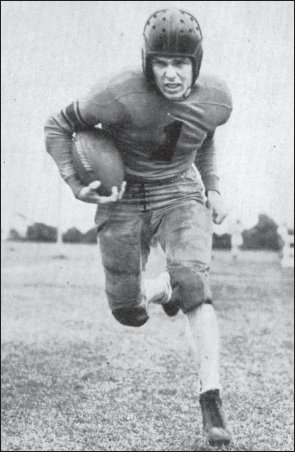

Benny Babula in his gold Garfield jersey. Newark Public Library (NJ) Newark News Photo Archives.

Benny and Violet outside Garfield High. Newark Sunday Call.

“Where the heck is Pending?” Babula asked, filling the locker room with howls.

The ironic truth was that Babula wasn’t all that crazy about football. He enjoyed the camaraderie with his teammates as well as the satisfaction of accomplishment that football offered. His favorite sport, however, was baseball, and he dreamed of a career as a power-hitting outfielder in the majors.

“Football’s silly to me. It’s a wearing game,” he told Willie Klein of the Newark Star-Ledger in 1939. “It’s not that I’m afraid of injuries. I am solidly built and plenty rugged. I’m not so easy to hurt. But somehow football doesn’t click with me. I guess if I quit football, I would miss it.”2

That same article disclosed a few other things about Babula. His favorite subject was chemistry, and he liked to tinker in the lab. His least favorite was French. Klein’s feature included another revelation: “It’s not generally known but Benny, the cynosure of all feminine eyes at Garfield has a steady girlfriend. She’s Violet Frankovic, also a student. They’ve known each other for years.”3

Over 75 years later, Violet—who had gone on to marry Joseph Kolbek, a Garfielder six years her elder—recollected her time with Benny with a laugh. The papers, she said, embellished their relationship as papers did then. They hardly interacted at school, she said, only to wave at each other, but they did date after she had obviously caught Babula’s eye. Violet, attractive and three years younger than Benny, was just 15 when they started to date. Her father, Butch Frankovic, head of the Garfield Indians Athletic Club, was understandably protective, but Benny, she said, “was a perfect gentleman” who adhered to her father’s rules.

John Grembowitz

“He treated me very well, he took me to such nice places,” Violet said. “Benny had a way of getting a date. He would say, ‘Violet, how would you like to go to Asbury Park for the day?’ and I would say ‘lovely.’ ‘I’ll pick you up nine o’clock on Saturday,’ he’d say. All of our dates were all day on Saturdays. So we went to Asbury Park, and we went on the merry-go-round and he bought me some taffy to take home. And then the next date was: ‘How would you like to go to Palisades Park?’ Also on Saturday.

“We went on a couple of rides there, and I didn’t even tell my father we were going on the Ferris wheel,” she said. “We stopped at the games. It was three balls for a quarter and, naturally, he hit all three balls and we came home with a stuffed animal. He always got me home by suppertime.”

Babula always picked up Violet in his DeSoto. Only two players on the team had cars. Benny’s family was more well-off than the rest, but he didn’t flaunt it. No one was jealous; Babula always put his teammates above himself.

“Me rated with the best backs in New Jersey school football history? Aw, I’m not so hot,” he told Klein.4

Besides, Babula’s teammates were pretty hot themselves. In 1939, Babula ran for more than 880 yards, passed for more than 400 and scored 118 points, not including the Miami game—the highest among New Jersey Group 4 players in the regular season. Without him, Garfield would not have played for a national championship. But Garfield was far from a one-man team.

John Grembowitz was born in Passaic and was in school there when, in 1929, his father Frank was killed in a car crash, leaving their Prohibition-era soft drink business to his mother, Katarzyna. That same year, Joseph Klecha lost his wife Maryana to cancer, leaving the widower with four kids. He was also a beverage distributor and, in 1932, he and Katarzyna married and had a son, Frank. John and his sister Mildred became step-siblings. John would now have two older siblings (Michael and Ed) and two younger ones (Stanley and Sally), making it a yours, mine and ours arrangement.

Prohibition ended in 1933, and Joseph Klecha opened one of the scores of taverns that suddenly proliferated in Garfield. It was on Ray Street, a short walk from the Forstmann plant and up the street from St. Stan’s Church. Butcher shops framed the block and a bakery was across the street, making Ray Street a bit of a commercial hub. A lot of passersby were thirsty. Klecha’s Tavern did a good business.

“He was a friendly, jovial happy go lucky guy, my Dad,” Sally said of her father. “He’d sing, tell jokes, make music. Everybody called him Mr. Klecha. He always wore a white shirt behind the bar and my mom made sure they were always washed and ironed. We were a very happy family. There was a lot of togetherness.”

The tavern was out front, and the family lived in the back with a little flower garden in the backyard that Katarzyna kept. The boys shared a room and beds—and work. Running a tavern wasn’t easy, and everybody chipped in. The boys washed and dried dishes and glassware and hauled around boxes of stock. Their chores had to be done before football practice.

John and his brothers liked to fish and would occasionally take Sally and little Frank along to their favorite spot under a big oak tree by the Passaic River. “He was so nice to me and so handsome,” Sally recalled. “He was very outgoing and he had a lot of girlfriends.”

Sally attended St. Stan’s, where stern nuns presided in the classroom. John and his brothers attended nearby Washington Irving School No. 4, where teachers changed the original spelling of his name (Grembowiec) to a more phonetic Grembowitz. St. Stan’s had a gym in the old church building where Johnny held court, playing basketball and the like. But his strength, quickness and smarts suited him for football above all the other sports and having older brothers accelerated his learning curve.

Ed was a fairly talented football player, as well, so one can imagine Art Argauer’s glee when Ed told him about his kid brother, a year younger than him. Grembowitz and Benny Babula were the only two freshmen to play in varsity games in 1936 and became good friends. Babula would often drive by the tavern and the two would head out together.

Grembowitz had both classroom and football smarts. On the field, he had a knack for sorting out a play, which is why he was able to move seamlessly between the line and backfield whenever Argauer needed him. He combined his great instincts with a tremendous first step. He was fearsome as a pulling guard, and on defense he had great closing speed that enabled him to run down ball carriers otherwise headed for big plays.

“There was no question that Johnny Grembowitz had something special,” Walter Young remembered. “He was just a little different than all the rest of the kids on the team. I think it had to do with his intelligence, I think it was just a notch higher than most of the kids on the team. And he played with extreme confidence.”

Both Babula and Grembowitz were named to the 1939 All-State team along with a third, more unassuming player, who made honorable mention. Walter Young wasn’t a typical Garfield boy in that his parents weren’t from Italy or Eastern Europe. They were German immigrants from what would later become the German Democratic Republic, or communist East Germany. Young’s father, Martin, was one of five boys, two of whom would be killed in World War I. His parents owned a small farm—cows, chickens, and earth crops—but it was to be passed to the oldest son and that wasn’t Martin. Martin was a loom fixer (mechanic at the nearby woolen plant) and, when work was tight, he received a letter from America from his brother, Franz, who worked at Botany Worsted Mills in Passaic. Botany, a German-owned company, hired mostly Eastern Europeans for its less-skilled jobs, and Germans for managerial and technical positions. All of Botany’s looms were German-made, and its maintenance manuals were in German, which made Martin a superb candidate for employment. So, Martin Jung (the name was Anglicized to Young upon arrival) left his family in order to provide for it. As with many others, he never again saw his parents.

Two of Martin and Ida Young’s children were born in Germany: Elsie in 1910 and Curt in 1913, with whom Ida was pregnant when Martin sailed to America. For two years, he sent money home, a few dollars at a time.

“I have a postal card that my father wrote to my mother,” Walter Young said. “I smile over that card because I recognize that my father was a typical, stiff-necked German man. I loved him deeply, deeply. He wrote to my mother, he sent her some money, twenty dollars. He wanted her to keep it to buy a ticket. “Dear Ida—it’s as if he was talking to a strange person, there was no feeling of ‘My beloved Ida’—then, ‘I hope everything is OK, you know I’m working hard. Say hello to my children …’ Nothing about ‘I miss you.’ It was just stiff and cold … incredible.”

But that hard exterior betrayed his father’s actual feelings. While Martin was in America, little Elsie contracted scarlet fever and died. Ida was devastated in her grief and unable to send immediate word to her husband. Forced to leave Elsie behind in her churchyard grave, she and Curt would join him in New Jersey. Curt celebrated his first birthday on the ship. At first they rented rooms in Passaic. Then, when Martin saved enough from his earnings, they bought a two-family house in the Plauderville section of Garfield, on Bergen Street. That’s where Rudolph, in 1919, and Walter, in 1922, were born. Their father, though, never forgot his first-born. If ever Elsa’s name would come up at the dinner table, this stoic German who believed that emotion was not permitted, became silent, Walter remembered. He never knew his sister but through his father’s teary eyes.

The Young family lived in the upper two floors of the house on Bergen Street. It was a typical Garfield arrangement: two bedrooms, a living room, a kitchen without appliances and a half-bathroom. Heat generated from a coal-burning stove in the kitchen. Walter and his brother Rudy shared a third-floor room, oppressively hot in the summer and, in the winter, nearly as cold as beyond its walls. Their mother heated bricks and placed them underneath their featherbed.

“We told stories, made mischief but slept in a very warm bed,” Walter said with a grin.

Out front, Walter’s “Papa,” as he was called, built a retaining wall about three feet high, and, behind it, planted a sour cherry tree the boys were forbidden to climb. There was one enticing branch which could be reached with a jump from the retaining wall, and, naturally, they would swing and horse around on it. It was all innocent fun.

Martin Young was often out of work and he brooded over it. He was a proud and frugal man. Instead of wasting a nickel for bus fare, he walked the two miles each way to the Botany factory. One hot summer day, Walter craved an ice cream cone from the grocery store/ butcher shop on the corner. He asked his father for five cents and, after much pleading, his father reached into his pocket and pulled out the only nickel he had on him. Walter, with holes in both pockets, cleverly stored the coin in his mouth and sprinted across the unpaved street. Too eager to get to the store, he tripped in a gully and swallowed the nickel. His disappointment, he remembered, was “beyond measure.”

The proprietor of that butcher shop soon found Walter rather troublesome. As with many in Garfield, Ida Young sought work outside the home. She found it washing clothes and cleaning house for a well-do-to Passaic family, the Prescotts. Heirs to an empire built on stove polish, they were so prominent that one of the local telephone exchanges was named after them. Without that household job, the Youngs would have defaulted on their mortgage. Ida was a fantastic worker and the Prescotts, as kind as they were, often gave her hand-me-downs from their son, James Jr., for her boys. Once, Walter received a fine shirt that he ripped playing football with his friends. Another time, when he was about 10, he got a golf club and some balls.

“This was like Christmas for me,” he remembered. “These things we did not ever have an opportunity to see, much less own one. So when I got it, I showed all my buddies and we walked down to the corner. That’s where the children in the neighborhood came together, right in front of the grocery store and the bus stop.”

Young wanted to show everyone how to hit a golf ball so he put it on the ground with the store behind him. Unfortunately, Young wasn’t familiar with hitting down on the ball to create loft so when he smacked it with a mighty cut, it ricocheted off the curb, back over his head and into the store window with glass shattering everywhere. The butcher ran out, but Walter wasn’t there. He had already picked up his club and started to run. He dashed straight up Midland Avenue past the Pump House and then up the hill into “Guinea Heights.”

“There were no homes built there yet. I am up on the top of that hill crying and I am afraid to go home,” he explained. “I am up there for hours; that’s how big of a disaster it was for me. ‘What is my mother going to say? What will she think of me?’ I ultimately have to go home. My mother is crying. The butcher already knew that I did it from other kids that were there. What drama something like this was to this little kid. But it had a reasonably good ending. The butcher had insurance. There was no way that my mother and father could have afforded to replace that window. I don’t remember if I kept the golf club. I never played often enough later in life to be good at golf.”

That same butcher figured into another of young Walter’s adventures. Like many “house-rich, cash-poor” Garfield homeowners, the Youngs took in boarders. One was a smoker, which fascinated Walter. He offered the boy a few puffs just as Ida Young was getting off at the bus stop on her way home from the Prescotts. She saw Walter with the cigarette in his mouth.

“Who gave you that?” she asked angrily.

Walter stammered.

“The butcher.”

That night, Ida dragged her son along to visit one of her lady friends down the block. As they passed the store, the butcher said, politely, “Good evening, Mrs. Young.” That set her off. Turning abruptly, she admonished the man. “Why did you give my son a cigarette?” The butcher said he didn’t. Ida pressed Walter: “Did he give you a cigarette?”

“Yes,” Walter answered.

It wasn’t until a couple of blocks later, after his mother had walked off in a huff, that he fessed up.

“I still have the dread of having lied to my mother,” he flinchingly recalled. “It was such a life-changing event that, even when I tell you the story now, I feel like I felt as a kid, almost 85 years ago.”

Walter grew up in the New Apostolic Church, a strict chiliastic Protestant sect that flourished in Germany. Young’s parents were devout and, as such, his guilt would have been profound. In fact, one of the most traumatic episodes of his childhood came while walking home from the church in Clifton with his Sunday school attendance card, which recorded attendance with a gold star for being on-time, and a blue star for tardiness. A dreaded red star meant no attendance. Walter’s card was full of gold stars, and he treasured it. The route home, however, took him over the Dundee Canal and the Passaic River. He and Rudy always leaned over and spit down from the bridges. As Walter did so, his attendance card fell into the Passaic River. He could have cried.

Walter Young

The church almost prevented Young from playing football. Most Garfield boys played football and baseball on the many empty lots around the city, which made for a lot of skinned knees and scar tissue—not a bad preparation for further athletic endeavors. Walter and his brother were no different and, since Rudy was older, Walter often went up against older kids. He was big for his age and he could tell he was cut out for football. At the time, he was attending No. 8 School, where the high school team’s locker room was a short walk to the practice field at Belmont Oval. He looked out the window one afternoon and saw the Boilermakers boarding the team bus, resplendent in their purple jerseys. That’s when he promised himself to try out for football.

“I looked at those kids and I wanted to be one of them so bad, you couldn’t believe it,” he said. “I overcame all the obstacles put in my way; my mother didn’t want it, my father didn’t want it, my brothers didn’t care. They didn’t play. Above all, the church was not in favor of it. But I was determined and I never quit getting after something. It was my target. I wanted to be like those kids with clean uniforms, purple and gold. I could hardly wait to get these shoulder pads. Wow, I was going to be a football player.”

Young became a football player and a good one, good enough to start varsity as a sophomore and to make several all-star teams as a senior. The end position was the key to stopping the outside running plays that most teams ran. It required discipline and cleverness. Young never made the same mistake twice and, for all of his good nature, he was competitive, tough, and trustworthy.

Young was also a good student and enrolled in the technical program, considered at the time one of the most advanced academic programs at Garfield. One of his best friends was Walter Bradenahl. They attended Sunday school together at the New Apostolic Church. Walter was born in Mannheim, Germany, and the Bradenahls came over from Berlin in 1927. The two Walters were an interesting pair together. Young was tall and well-built and Bradenahl was on the frail side. As friends, they did all the typical boy things together. Bradenahl was less inclined to rough-housing and sports, but Young appreciated the discussions they often had.

“He had a brain that was most unusual. He was the smartest kid in the school,” Young recalled.

Bradenahl was an only child who worshipped his father, Walter Sr. The father ruled the roost. Young remembers how his friend would say: “My father is going to do this, my father is going to do that.” Meanwhile, Bradenahl’s mother, Frieda, was someone Young called, “a typical German housewife who relied totally on her husband. What he said was Gospel.”

Young and Bradenahl were in the same civics class as sophomores. That’s when he noticed a change in his friend’s demeanor and attitude.

“There would be a discussion on world affairs and he would challenge the teacher on which system was better, the Nazi system or the U.S. system,” Young said. “There would be this real vigorous discussion … no anger … but a real good debate and then on the way home, I would tell Walter: ‘You’ve got to slow down.’ But he never did.”

Bradenahl’s father could not find a job in his field, engineering. At the same time, he was receiving letters from Germany extolling the virtues of national socialism, urging him to return and promising him work. The elder Bradenahl swallowed the propaganda littering those missives. He fell victim to age-old, scapegoat anti-semitism, blamed the Jews for controlling everything in the United States, including his own lot. A decision was made. The Bradenahl family was returning to Germany.

“His father was taken in, completely and totally … and really, what does a kid know?” Young asked. “It was clear that they talked about it at great length in their home. I know for a fact that his mother did not resist her husband’s plan to return to Germany. She might well have been homesick, and the idea of returning to Berlin might have been appealing. And Berlin at that time was a tremendous city and a great city to live in. All of Germany was spotless … until the bombs started to fall.”

Bradenahl tried to persuade Young to move his family back to the Fatherland as well.

“I did not really know what Nazi meant, other than what we talked about in high school when we discussed world affairs,” Young said. “I knew there was this upset in Europe but nobody knew what the extent was. My mother had a brother in Germany and they would be very intrigued when a letter would come in. But it was more normal things. I don’t remember any discussion in our family concerning the heroics of Germany versus the United States. My father and mother were not influenced. There was no evidence, and we never discussed it, although I don’t know what they talked about amongst themselves.”

In preparation for the move, the Bradenahls left Garfield for Linden, New Jersey. Young would receive two last letters from his friend, one from Linden and the other from the United States Lines ship taking them back, each one indicating a deep descent into Nazi groupthink and a naive unawareness of what lie ahead.

The first, dated June 8, 1938, written with a fountain pen in neat script on graph paper, bragged that Linden High was “100 percent better” than Garfield High with more activities and better mechanical drawing equipment. He complained he never could draw a straight line with some of the T-squares Garfield stocked and, whatever supplies there were, were shared. He also asked Walter for a favor: to tell “little Lisa” not to forget him and to write. He lamented that he cried when forced to return a pet dog just one week after getting it from a neighborhood family.

Then, the letter grew disturbing:

Now the most important thing. I am leaving for Germany in a few weeks. And before I regretfully bid farewell to this “glorious land of the free and the brave” to this “God’s own country” and this earthly paradise, I will come to visit you. We’ve sold most of our furniture and we’re staying in Hitler’s land “of oppressed souls and medieval persecutions” where people starve so badly that they win Olympic Games and vote 99.08 % for their leader and build their own vacation ships (workers’ contributions built two large liners for service in the “Strength through Joy” movement.) I will probably serve in Mad-man Hitler’s bloody horde of sadistic, blood-man murderers who eat fried Jews’ noses for breakfast. I will join the Hitler Youth, then the Arbeits Deinst (sic)[Arbeitsdienst, or Reich Labor Service], then the Army. Though I must first complete my education. How I will miss our glorious freedom, our happiness and prosperity … No, I’m afraid we, having been reared under tyrannical Prussians, are too far gone to appreciate the wonderful circumstances under which we might exist but our terrible and mystifying affliction bids us leave all blessings behind us for that “dark pit of rejuvenated Medieval outrages.” Ah, me!5

The letter continued for two more pages. With a less sarcastic tone, Bradenahl outlined the reasons they had to leave, that his father’s foreign accent rendered him unemployable in American offices and that he had no future himself in an America with “no pull.”

“What was left for me? The CCC, the WPA or street digging. No, my lad, I’m shooting high,” he wrote.

Germany, Bradenahl told his friend, needed engineers and its government agencies ruled that factories hire a workforce comprised of both young and old. Workers could retire at 60 on a government pension.

But then those poor souls don’t have our wonderful freedom: we have only 11 million unemployed and only 80 per cent of our people are mentally below normal (I quote an American doctor), we only have a few hundred sex crimes a year and we only execute about 1,000 a year (it could be a lot worse, couldn’t it?) But maybe my wit is rather caustic—let it ride.6

Then Bradenahl instructed Young to tell his Garfield classmates he’ll be visiting them one last time, “particularly my wonderful history class—boy what arguments, but I always came out on top.”

He signed it, “Mit Deutschen Grusse (with German greetings), Walter Bradenahl,” and added, “Remind Lisa that I still exist.”

Bradenahl never made it back to Garfield. His next letter was dated June 16, eight days after the first. He was on board a ship of the United States Lines on his way to Germany. He joked about how his handwriting was crooked because of the ship’s movement and said his family should have taken a German boat. He wrote about watching movies and playing shuffleboard and ping pong. He ended, “until the next letter then, I am, Yours Truly, Heil Hitler, Walter Bradenahl.”7

Young never heard from his friend again. He tucked the letters away and thought often of him.

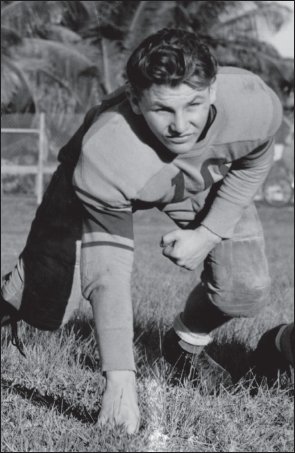

John Orlovsky

Walter’s best friend on the football team was Jack Boyle, the left guard. Boyle’s father, Francis, was a first-generation Irish American, who, like many Irishman, went into police work. At 21, he was one of the first officers of Garfield’s police force after it was formed in 1908. He quickly rose up the ranks. In 1915, he was awarded the Wood Mcclave heroism medal for single-handedly thwarting four burglars as they tried to break into a store. He was captain of detectives during the turbulent 1920s, including the textile strike of 1926 and was deputy police chief when he died in office in 1940. Jack was with Young in the technical program at the high school. He was, Young said, “a scholar.”

He was also someone of character. Harry Berenson was a small Jewish boy whose father, Sam, owned the dry goods store on Passaic Street, around the corner from the Boyles. There were few Jews attending Garfield at the time, and his slight build made him a target for bullies—until Jack Boyle stepped in. Boyle told anyone who wanted to pick on Berenson that he’d have to go through him first. That ended it. Nobody messed around with Jack and as such, he was an ideal Argauer player. He became a starter in 1938 and never relinquished the job.

Miranda, the left tackle, was a tough, stout Italian American. He never came out of a game his entire high school career. Maybe it was because he was the second-youngest of six sons, but Miranda was used to doing the dirty work of straight-ahead blocking on offense and run-plugging on defense. He and center Pete Yura were newcomers to the starting lineup in 1939, but were always strengths from the season’s first game. As the center in the single wing, Yura’s responsibilities went beyond those of a modern center, including long-snapping on every down. He had long legs providing a wide base, and he was seldom moved. There was very little penetration into the Garfield backfield.

Bill Wagnecz and Joe Tripoli began the 1939 season as starters at right end and right tackle, respectively. Ed Hintenberger and Alex Yoda eventually moved ahead of them on the depth chart, although Wagnecz and Tripoli still saw considerable playing time. Argauer liked to substitute liberally to keep his team fresh and to prepare for injuries. That’s how young Steve Noviczky, a baby-faced freshman and a future Garfield High Hall of Famer, broke in at right guard, replacing Grembowitz when he was moved into the backfield for injuries there.

Tripoli was a giant of a kid—6-feet-1 and a team-high 205 pounds—who had just moved to Garfield from Montvale, where he won the Bergen County discus championship for Park Ridge High School. He was from an affluent family. His father had a seat on the New York Stock Exchange, but, shortly after the crash, he suffered a heart attack and died. That left Joe the only male in the family, with six older sisters. He was living with his mother and overprotective grandmother, who insisted he not participate in after-school activities. That led to some heated arguments and resulted in Joe’s mother, Frances, moving to Garfield to live with Joe’s sister Marianna and her husband Santo D’Amico.

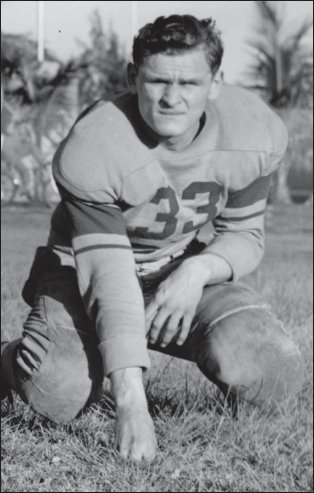

Ray Butts

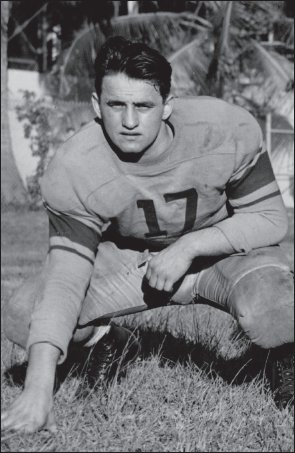

Wally Tabaka

Tripoli had a car and, at times, he’d be asked to babysit his four-year-old niece Rosalyn D’Amico and he’d bring her to practice. She became the unofficial mascot of the team, playing off to the side as the boys went through their paces. Those days were among her earliest memories. So was the time when Tripoli was driving home and his car stalled out on the middle of the railroad tracks. Luckily, he got it started before a train came rolling by.

The Garfield backfield was deep behind Babula with Wally Tabaka, Ray Butts and John Orlovsky in the other starting spots. Tabaka was the next-best runner and a threat as a return man. He was the shortest player in the starting lineup at 5-7, but he was sturdy 170 pounds. He ran low to the ground and was hard to knock down. He had also had guts to try, in an ever-innocent way, to move in on Benny’s girl, Violet.

“One day I was walking home and all of a sudden there is Wally and he is walking with me,” she remembered. “We started having a very nice conversation about our classes and about our teachers and we did that for over a week. Then Wally said, ‘Violet, I won’t be walking with you for a while now because we have football practice. But I have something for you.’”

Tabaka took off his varsity letter. Violet said she couldn’t take it. He insisted. She took it home and put it in the drawer.

“I never told my father about it,” she said.

Ray Butts was an inch taller than Babula and just as heavy. He was primarily the blocking back, although he had huge hands that made him a receiving threat. He started at end but was moved into the backfield to fill a need. Butts was the youngest of nine children by four years, 20 years younger than his oldest sister Irene. In fact, two years after Ray was born in 1920, his sister had a son, Ken Marek, who starred for Garfield just after Ray graduated.

Butts, however, didn’t come from the biggest family among his teammates. Reserve back Al Kazaren was one of 10 children. It wasn’t uncommon. Neither was losing parents. Kazaren lost his father at age nine, while Ray’s father, born Andrew Bucz, was a bus mechanic who was left with a house full of kids, including 10-year-old Ray, when his wife, Catherina, died of intestinal cancer in 1932. It was tough supporting the children still living at home. Like many teammates, Butts usually ate his lunch at the hot dog cart that was parked outside the high school. It was all he could afford—hardly a nutritional training table.

John Orlovsky, the youngest of four brothers, was raised without a father. His mother, a native of Russia, could not spell well, so the family’s surname was listed differently on each of her four childrens’ birth certificates. At 5-9, 185, Orlovsky was a very tough inside runner who constantly had to battle through a chronic shoulder injury. Like Tabaka, was very good on spinner plays out of the single wing.

What all team members shared was an admiration for their coach. Walter Young said it “bordered on hero worship.”

“Every once in a while you run into someone who affects your life. Coach Argauer affected my life,” Young said emphatically. “There were things he demanded that were absolutely the way it should be. What he did, how he represented himself … he was above reproach.”

Before each game, the players would go into his office, one by one, and he would tape their knees and ankles himself, all the while talking softly and calmingly. He’d remind the player of his responsibilities and emphasize the little things he needed to remember. He was meticulous in that respect. Similarly, he was a big proponent of game films. A camera buff himself, he enlisted another enthusiast from Garfield, Michael Rayhack, to take the pictures. Rayhack even experimented with color photography. It could be said that Argauer gave him his start on his career. When World War II broke out, Rayhack joined the Signal Corps as a photographer and took a famous shot of General Douglas MacArthur aboard a destroyer. After the war, he became one of the top cameramen in the early days of television and worked on such shows as the Phil Silvers Show, the Avengers, Shari Lewis and Lamb Chop. Argauer knew talent when he saw it.

“Coach Argauer worked at a game plan all the time,” his assistant coach, Joe Cody, said when the team celebrated its 50th reunion in 1989. “He never left anything to chance. The man was a master of psychology and could sell the players anything he wanted. He was a coach way ahead of his time. He even installed a special play for every game which he guaranteed would win a game if needed.”8

Babula, at that same reunion, recalled one particular Argauer ploy before a big game against Bloomfield.

“He was so shrewd in getting you up for a game,” he said. “He chased everyone but the regulars out of the locker room. He said, ‘I’m going to give you guys a pill which you can’t tell anyone about. It’ll make tigers out of you. After you take this I want you to make sure you don’t hit anyone too hard because you may hurt them.’

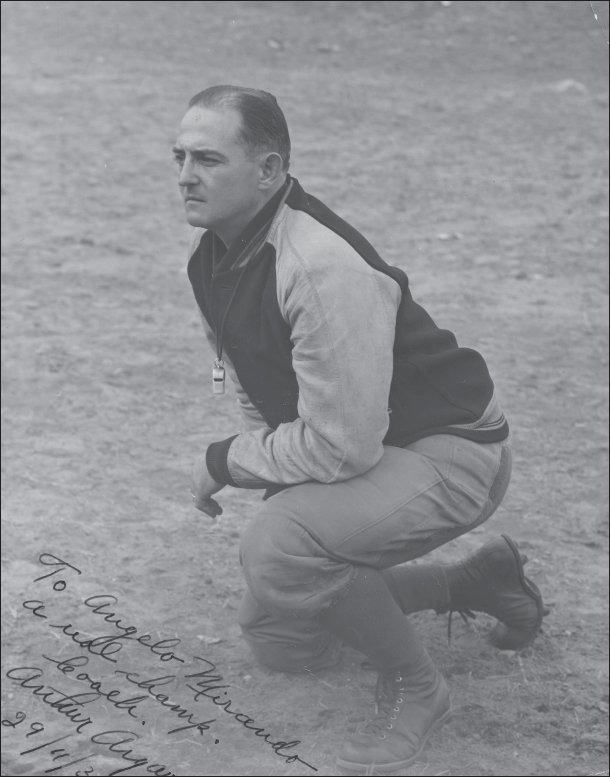

A kneeling Art Argauer in his coaching togs at Passaic Stadium.

Courtesy Angelo Miranda collection.

“I guess we bought his story because after swallowing the candy pills, we held Bloomfield to minus yardage and won, 18-0.”9

Argauer didn’t tolerate misbehavior. Get caught smoking and drinking and you’d find yourself benched, then off the team. “He said thing like, ‘keep yourself clean,’ ” Young recalled.

Practices were practically as hard as games. He didn’t lay off the contact. He presided over them with a rolled-up piece of cardboard. Mess up an assignment, and the player would find himself getting slapped on the hindquarters. That led to a memorable incident. When Argauer’s mother, Emma, heard that he was swatting his boys, she marched down to Belmont Oval and scolded him in front of the team. If anyone found it amusing, they didn’t laugh.

“We dared not,” Young said.

Later in his career, the cardboard became a wooden paddle. He called it the “board of education.”

There were always lessons to be learned. One day, Steve Novizcky wasn’t at practice. That was a no-no with Argauer. He asked the team where he was. Someone piped up, “He’s home coach. Mr. Novizcky won’t let him go to practice until he’s finished painting the house.”

Argauer thought for moment. He put the equipment on the side and gathered the team together. They all walked over to the Novizcky house on Willard Street, grabbed paint brushes and finished the job.

Art and Florence never had children of their own, so his players were his family. In 1946, he had proudly collected 3,000 letters from former players filling him in on their progress in college or the military. In a community where college educations weren’t highly prized or easily afforded, Argauer, as someone who came by his education by chance, valued it.

“Argauer was a great believer in college and worked very hard to get us in,” said Bill Librera, Babula’s backup, who pursued a career in education.10

“If it wasn’t for football, none of us would have been able to afford to go. We owe a lot to Art Argauer. There is not one single thing that I could think of that would be negative about Coach Argauer,” Young said. “He wanted the best kids on his team, he wanted to win, but that is what every coach wants. As far as his actions, he was absolutely above board.”

After being with Argauer since their freshman years, the seniors on the 1939 team were ready for anything.

Stingarees

He was a scrawny but scrappy 14-year-old when he walked up to an unsuspecting Jesse Yarborough in the Miami High gym. It was December of 1935. His husky brother, Knox, was the captain of the Stingaree football team, eventually bound for All Southern honors and stardom at the University of Georgia. The coach had seen the youngster around, but he was hardly prepared for what Davey Eldredge was about to pronounce.

“Some day, I’m going to be a better football player than Knox,” he predicted matter-of-factly.11 Yarborough chuckled. ‘Confident young man,’ he must have thought. Four years later, the kid was right. Davey Eldredge turned out to be a better football player than almost any Yarborough had ever coached. He epitomized Stingaree football—small, smart and swift— and was the perfectly cast for the Orange Bowl lights. The field was his stage, and he dazzled on it. He brought the crowd to its feet every time he touched the football, always a threat to go all the way. Arguably, there wasn’t a more exciting high school player in the nation.

As a 5-feet-11, 151-pound senior, he was “Li’l Davey” the giant killer. To television viewers in the 1960s, he would have looked as innocent as Dennis the Menace—until he strapped on the leather helmet, glared at the opposition and started his engine. Miami Daily News sports editor Jack Bell called him “a galloping waif,” while the Associated Press was already comparing his explosiveness to that of the great Red Grange.

“He could almost be standing still, then go ‘whoosh’ and blow past you better than anyone else I’ve seen,” said his teammate, Harvey Comfort. “He could really turn on the steam.”

Davey Eldredge.

Miami Senior High School.

The one characteristic Davey shared with his brother Knox was competitiveness. Knox famously started a bench-clearing brawl during Georgia’s 1939 game against NYU at Yankee Stadium after colliding with a Violet player on an incomplete pass. Depending on which newspaper reported it—north or south—either Eldredge responded to a punch thrown by NYU’s Joe Frank, or he struck the first blow with a forearm to the face. In any case, the scuffle sparked a Civil War in The Bronx.

“It was plain that they held the NYU players personally responsible for Sherman’s march and the undoubted evils of the reconstruction period,” joked Tommy Holmes of the Brooklyn Eagle.12

The younger Eldredge possessed the same type of fighting spirit, inherited from both sides of the Mason Dixon line. His mother, Jennie Belle Turner, was from one of the most prominent families in Tuscaloosa, Alabama. Her maternal second great grandfather, Uriah Farmer, was among the region’s pioneer planters. Davey’s paternal lineage included three Mayflower passengers while another ancestor, Samuel Smith, was a renowned sea captain in Wellfleet, Massachusetts. His namesake grandson, Samuel Eldredge, moved to the Orlando, Florida, area and married Mary Stewart, the daughter of David Bradwell Stewart, one of the first orange growers in Florida. They were Davey Eldredge’s grandparents and among the first settlers of Apopka, Florida. In 1895, the “Great Freeze” wiped out the orange crop and, with it, the Eldredges’ budding family fortune. That set the then seven-year old Alfred Stewart Eldredge, Davey’s father, on a self-made course.

Samuel, having turned from citrus growing into storekeeping, hoped his son would follow him into the merchant business, but Alfred, known better as “Red,” held loftier ambitions. Saving enough by working in his father’s store, he entered the Georgia Military Academy in College Park, Georgia, where he excelled academically, became a crack marksman, and played centerfield on the school’s championship baseball team. He earned admission into Georgia Tech, and, in 1908, played “scrub” football under the great John W. Heisman, sacrificing his body three times a week to prepare the varsity for games.13

Married a year later to Jennie Bell, Red Eldredge returned to Apopka and was eventually appointed livestock inspector. He led a successful tick eradication campaign by forcing wary cattle farmers to participate in the controversial practice of cattle dipping, often at his own peril from anti-dipping associations that were known to shoot officers and dynamite dipping vats. Surviving that, he served as city clerk and tax collector until 1917, when he homesteaded 120 acres of land known as Mill Creek Island. Eldredge made a success of it, fighting off bears with an appetite for his hogs. He later credited the invaluable help of a young black man, Ed Johnson, whom the family took in and treated like a son, an arrangement practically unheard of in the segregated South. But there he was, in now-lost family photos.

Alfred Turner Eldredge was born in 1910, William “Knox” in 1915 and David Cameron in 1921, by which time their father had moved the family to Miami, where he was elected city and county purchasing agent. It gave him standing in the community and allowed the Eldredges to live comparatively well during the Depression. They even had a summer cottage at Black Mountain, North Carolina.

His parents divorced in 1937 and, in 1939, Davey was living with his mother on the first floor of the Ruth Apartments, a small complex she managed in the Shenandoah neighborhood, not far from Miami High School. By then, older brother Alfred had been married six years to the former Mary Candler, granddaughter of Asa Candler, the Coca-Cola magnate and, with Knox off at Georgia, Jennie doted on her youngest child, the bright and energetic Davey.

Davey’s mother was active in Miami society as a member of the Brookfellows Literary Guild, the Miami Women’s Club, the Dade County League of Women Voters, the Florida Army of Democratic Women and the Southern Cross Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, of which she was president in 1932. As a boy, Davey would tag along at some of the events and was exposed to history, reading and music. Unlike his on-the-field personality, he was rather gentle and soft-spoken, and he made friends easily at Miami High, where he participated in three sports: football, basketball and track. He was active in the Key Club service organization, elected vice president of his junior class and voted most popular. In short, he was a model student, described by Jesse Yarborough as “orderly, courteous, very cooperative, level-headed and above all a very good student.” 14

Granted, the coach could have said the same thing about practically any of his players, who, for the most part, had solid upbringings and socio-economic advantages over their Garfield brethren.

Halfback Harvey Comfort, for instance, led a rather comfortable lifestyle, untouched by the Depression although not by tragedy. His great uncle was Walter R. Comfort. The “R” was for Rockefeller, his mother’s prodigiously successful family. The Comforts were among the earliest settlers of Newburgh, New York, and Walter made use of the sprawling dairy lands of Orange County to build a fortune in the ice cream business.

By the 1900s, Comfort was among the wealthiest men in New York. He soon saw an opportunity to expand his empire in the untapped, yet high-potential city of Miami. He and candy manufacturer John C. Huyler realized that the black muck soils of the Everglades were ideal for growing the sugar cane essential to both industries, and they partnered in scooping up 12,000 acres adjacent to what was then Miami’s municipal border. While their sugar cane visions never materialized, the land only soared in value. In 1917, the construction of the Comfort Canal drained 1,000 acres of Everglades that was used for farming and cattle ranching. When the land boom of the early 1920s hit, Comfort turned a nice profit by selling off 50 acres to Detroit developer J.A. Campbell, who, in turn, named the tract Comfort Gardens and subdivided it, touting it as one of the most desirable spots in Miami.

There, at the corner of Seventh Street and 34th Avenue (at the edge of busy Little Havana today), Walter’s brother—and Harvey’s grandfather—Harvey Daniel Comfort (all the Comforts shared in Walter’s success) set up a small farm. It wasn’t until Harvey was seven years old, however, that he got to Miami. His father, Harvey Harrison Comfort, had remained in Orange County as an executive with the original ice cream company, and, in 1927, his mother Grace died of pneumonia. Not long after, the Comforts’ home in Newburgh burned down, and Harvey’s father moved the family in with his parents in Miami.

Harvey Comfort.

Harvey’s grandfather put him to work, feeding the farm’s 300 chickens and milking the two cows. Harvey became so accomplished he could hit a target by squirting from 20 feet away. Stored in stainless steel containers, the milk had an added benefit.

“I’d reach in there at the top and pull off the cream,” Comfort said. “I drank more cream than you wouldn’t believe. About 45 minutes before I left for a football game, I’d drink a pint of it. I had more good energy. I felt like I was cheating on those guys.”

The Comforts’ cow pasture also provided Harvey with his first football playing field. On Sundays, he started playing with a bunch of friends who, dodging the cow flops, called themselves the “Shit Kickers.” Future Miami High teammate Jay Kendrick was one of the gang and the games soon included a few Miami High players as well. The games were so good that passers-by would often pull over their cars and watch.

Kendrick, the other “Shit Kicker,” was a naturally-gifted lineman, a 225-pound strongman with a chest that measured 46½ inches when he later enlisted in the Army. If Eldredge was the offensive MVP, Kendrick was that on defense. No offensive lineman could handle him. He could break up plays in the backfield just by tossing his man aside. Even in high school, he had a deep voice, adding to the intimidation any opponent might feel.

“He was Mr. Special,” Harvey Comfort marveled. “He was so strong, a different guy than anybody else. He could grab anybody and pick him up by the back of the shoulders and throw them around like a tin can.”

Family lore had it that Kendrick’s maternal family, the Chandlers, ended up in Miami from South Georgia, because someone stole the family’s dog. Chandler supposedly got on his horse with his shotgun and tracked the thief all the way to Miami. Once he got there, he liked it and sent for the rest of the family. That’s where Lucile Chandler, Jay’s mother, was born in 1901. Jay’s father, John Pike Kendrick, was another transplanted South Georgian. Looking for adventure, Kendrick joined the Army and was part of the chase for Pancho Villa on the Mexican border, followed by a stint in World War I. He was back in Miami in 1920, when he married Lucile. Jay was born a year later.

The Kendricks opened a butcher shop/grocery store that did well enough for them to afford some land near Fort Myers. Unable to pay the taxes on it during the Depression, they lost it. Still, John Kendrick kept the store open and won a contract to supply all the greyhound tracks with meat for the dogs. There was always something cooking on the stove in the store, and their son Jay ate well—and grew well.

At Miami High, Kendrick became best friends with another brawny youngster. Mike Osceola was the second great-grandson of the first Seminole chief Osceola, nicknamed the “Swamp Fox” for his daring raids on U.S. troops during the Indian Wars of the 1830s. Captured under a white flag and sent to Fort Moultrie prison, the chief died there of malaria in 1838, a hero to his people.

A century later, Mike Osceola wasn’t a hero to his people, at least not in 1937, when he was the first Seminole to enroll in a public school, Miami High. The tribe resented him for it, but he proudly defied them. His father, Chief William McKinley Osceola, believed that public education was the right path for future Seminole generations.

Born in the Everglades, Mike lived in a hut until he was 10 years old when his family moved to open a trading post at Musa Isle, a tourist area just outside Miami on the Tamiami Trail. A man-child at 13, he wrestled his first alligator on a dare at a family wedding, and he was soon entertaining visitors to the trading post by throwing around 225 pounders. He became so adept that he toured up and down the East Coast during the summer months, nearly losing his head to one of the reptiles in a Niagara Falls exhibition in 1937. “I must have touched his tongue because his mouth snapped nearly shut,” he explained.

Mike had been encouraged by his father to learn the “white man’s” language and customs from an early age and taught him English out of a Sears Roebuck catalogue. Still, at 16, on his first day of school at Miami High, he had only a rudimentary knowledge of grammar and mathematics. He nevertheless worked hard with his tutors, including Jesse Yarborough, who took a genuine interest in him. So did track coach Pete Tulley, who attempted, unsuccessfully, to teach him the mechanics of the javelin throw. Undeterred, Mike brought the javelin back to the Everglades one weekend, so he could learn the art of spear hunting from fellow Seminoles. When he returned, he beat his previous best by 40 feet and became a champion, earning himself the nickname “Big Mike.”

“From then on, I gave up coaching,” Tulley joked.15

Yarborough did not. He turned the alligator wrestler into a football lineman. The hardest part was encouraging his aggression. Osceola was concerned that he’d hurt someone. Yarborough really helped him along, though and the two remained close always.

Osceola played in 1938 and again in 1940, when he really excelled. But, for some reason, he played only one game in 1939. He was mentioned in pre-season stories and was included in the team picture taken before the season but seems to have been ineligible, perhaps academically. In any case, he and Kendrick made quite the pair as they palled around with each other. Osceola even taught Kendrick the fine art of gator wrestling. They would strap a medium-sized specimen onto their bicycle handle bars and ride to one of the downtown theatres, where they would wrestle it onstage and get into the feature for free, according to Kendrick’s son, Bill. He didn’t know what they did with the gator in the meantime.

A number of other Miami players also had interesting family backgrounds but, for the most part, their fathers held down white-collar jobs. Tackle Dick Fauth’s father, Christian, was a German immigrant who became one of Miami’s leading furniture dealers. Tackle Henry Washington’s father, Raoul, was in the U.S. diplomatic corps, the vice consul to Cuba. Red Mathews’ father, Thomas, sold insurance. Tackle Doug Craven’s father, William, born in England, was the valet for Edmond A. Guggenheim and worked to keep the copper magnate in trim on his business trips to South America. Later, Craven became the chief steward on Guggenheim’s yacht, the job that took him to Miami, where he opened a boat shop. Doug, born in Brooklyn in 1921, lived briefly in East Rutherford before the family moved to Florida. Had they not, he probably would have played on the line against Garfield for East Rutherford High School. Square-jawed, Craven had rugged good looks and was a top-notch jitter-bugger and not unpopular with the girls.

Three Stingarees lost their fathers in their youth. For glue-fingered end Charlie Burrus and Paul Lewis, a reserve in 1939 (but a future Hall of Fame center), it could not have been more traumatic.

Mike Osceola, Stingaree lineman, in a publicity photo explaining football to members of his Seminole tribe in native dress at the practice field outside Miami High School.

Courtesy Larry “Mike” Osceola estate.

Burrus had just turned eight when his father Wendell Searcy, an insurance agent, moved the family from Tampa to Miami in November, 1927. A month later, he told his wife, Dorothy, he needed to travel to Jacksonville for a business opportunity. Once there, however, he told his roommate he expected never to see his wife and four children again and walked out with an empty glass and a bottle of mercury bichloride tablets. Despondent over his health and finances, Burrus was intent on poisoning himself. The roommate notified authorities, who found the 36-year-old man near death. His wife rushed to his bedside, where he was thought to be recovering. He died five days later.

Four years later, Dorothy remarried James Alva Hearn, a successful building contractor who provided Charley and his siblings a comfortable home life.

Paul Louis’ father, Louis Louis, had come to Miami from Key West with his father, Adolph, in 1923 and established A. Louis and Sons, a men’s clothier. The store had just been moved into more elegant quarters on Flagler Street when Louis Louis took a revolver and fired a shot into his chest. Although friends noted he seemed nervous for weeks, no motive for the suicide was established. The business was in sound financial condition. Paul Louis was just six years old. He was raised by his mother, Ruth, who also took over the store’s operation.

As Harvey Comfort did with his cow pasture buddies, Paul Louis started playing football with a neighborhood team called the 29th Street Bonecrushers. He developed the ability to make the center snap, and Yarborough quickly added him to the varsity roster as a 10th grader. His teammates nicknamed him “A-Loo” after the name of the men’s shop.

Lineman Gilbert Wilson, whom they called “Pretty Boy” as the best-looking guy in the school, was born in Chicago and christened Gilbert Cleary Hayes. His father, Curtis Franklin Hayes, a railroad worker, was crushed to death in an accident when Gilbert was just six years old. Gilbert’s mother, Felicia, remarried a Scot, John J. Wilson, who gave the children his name as the family resettled in Miami. Wilson was hard man and Gilbert often accepted his stepfather’s strict admonitions to protect his younger sister, Donelda. But there was one dictate he could not accept. When John Wilson prohibited his stepson from playing football at Miami High, Gilbert disobeyed him. He still worked in Wilson’s stonemason business but sneaked around him and managed to make every practice and game. John Wilson didn’t find out until Gilbert joined the team for a late-season road trip to Atlanta. He at last relented after watching Gilbert play in a game. Blessed with natural strength inherited from his natural father, Gilbert was one of the Stingarees’ best blocking linemen.

Sophomore back Gene Autrey (no relation to the singer/songwriter/actor) suffered the loss of a parent in a different way. His parents divorced shortly after they moved to Miami from Athens, Georgia, and he spent much of his youth in foster homes until reuniting with his mother and two siblings.

Reserve back Pericles Nichols, who was called “Percolator” because he stuttered, was the son of a builder, Gus Nichols, a Greek immigrant. Nichols, like Craven, was among those players raised in Miami’s outskirts. He, Red Mathews and Levin Rollins were all Alabama-born. Rollins’ father, Levin Sr., was one of 15 children, the son of a Dothan, Alabama judge. A train conductor who operated on some of the same tracks his father once helped lay, Levin Sr. moved the family to Miami after some time in the Panama City, Florida, area. George Rogers had just moved down from Ocala. And Harvey James arrived at Miami High after the school year started in 1939. James was from Savannah, Georgia and quickly earned the nickname “Geechee” after the distinct dialect spoken in the low country.

James’ reputation preceded him, athletically and as a troublemaker. His father, William, was never in his life. When Harvey’s mother, Catherine, became pregnant with him in 1919, nine years after their second son was born, William reacted by walking out on the family. The athletic Harvey ended up under the wing of several Savannah coaches who looked after him but, for some reason, they couldn’t keep him on the straight and narrow. Harvey had a difficult time at Benedictine Military Academy, where he would not be harnessed by the tight reins held by the Catholic monks. Although he starred on the football and baseball teams as a center and catcher, respectively, he was eventually expelled for unspecified bad behavior. His mother then sent Harvey off to live with a family she knew in Miami, the Melchings. Jesse Yarborough, no doubt, was delighted.

Jason Koesy’s father, Szilard, emigrated with his family from Hungary when he was 12 and settled in Cleveland, eventually marrying an Ohio farm girl before moving to Florida. Szilard Koesy worked in real estate until the market went bust, then for Florida Power & Light. The Koesys first lived in a two-story building on 15th Street and, while Szilard was at work, Lola, his wife, ran a small grocery store on the first floor. The shelves were stacked with canned goods in front of bushels of fresh produce. The store also stocked meat, butter and eggs. By 1939, they had closed the store and moved to a fourth home in the Citrus Grove neighborhood while Szilard worked for the city of Miami as clerk in the water works department.

“During the Depression, he had a steady job,” explained Jason’s younger brother, Calvin. “It didn’t pay very much but we stuck together as a family. We had meals together every night as a family; we were all together around the table, Dad was a good father authority, he made us kids toe the line. And we kind of managed to get through the tough times. Every one of my brothers and sisters graduated from college.”

As the family eventually grew to include seven children (Barbara, the youngest, was born in 1934), Jason, the oldest, was left in charge of the rest when his parents were away.

“We respected him and we did what he said,” Calvin noted. “I can never remember him getting into trouble and he was an A-student in high school. When I came along four years later, the teachers would tell me, ‘I remember Jason. I hope you can do as well as he did.’”

Koesy did have a brush with trouble, and it almost cost Miami High its best passer. The Koesys always had a Fourth of July celebration and would send away to Ohio for fireworks. When Jason was 14, he paused to see if a firecracker fuse was lit. It exploded in his hands but he somehow escaped serious injury. Spared, Koesy saw considerable playing time for the Stingarees beginning as a sophomore in 1937. But he played the same quarterback position as Eldredge did and played less than he would have otherwise.

They were, to say the least, a disparate bunch, bound by a common cause. Just as their Boilermaker counterparts, the Stingarees revered their coach. Jesse Yarborough may have had a softer exterior than Art Argauer but he was, without question, the boss.

Arnold Tucker, the great Army quarterback who played for Yarborough in 1941, said that Yarborough, “was not rough or mean but was very exacting in his communicating what he wanted from his players. I’d like to use the word disciplinarian but he didn’t really discipline his players, he was more exact, with determination … drive, give your best. He demanded the best of an individual.”

“When he walked into the room, everyone stood at attention,” Harvey Comfort explained. “He wasn’t a badass. He was a gentleman. But he was very regimented. You either did it his way or you didn’t do it. He just made it a point that, ‘this is what you were going to do.’”

A perfect example was the few times the Stingarees travelled to away games. Before each of those trips, Yarborough held a team meeting to make clear what was expected of each player; that they were representing Miami High. For starters, everyone was required to travel in jacket and tie. He didn’t want anyone blowing his nose in public or walking around with a toothpick in his mouth. Above all, no one could be caught smoking, even though, like Art Argauer, Yarborough enjoyed his Chesterfields and attempted to hide that vice from his team.

In The Stingaree Century, his history of Miami High, author Howard Kleinberg quotes several players. They paint the picture of a master psychologist.

Bruce Smith, a star on the 1941 team and, later a Navy Rear Admiral, noted that Yarborough prepared his players not just for football but also for life, “for living properly and studying.” He could be intimidating, but Smith noted he knew how to handle different personalities. He’d shout at those who needed it, and let up on those who wouldn’t react well.

John Oakley, a sophomore on the 1939 team, recalled an incident a year later in this excerpt from The Stingaree Century:

“We were up in Jacksonville for a game and I was roomed with Bruce Smith,” he said. “I had a tendency to smoke now and then and there comes a knock on the door. I flipped the cigarette in the toilet and flushed it. In walks Yarborough and he asks: ‘Who’s smoking in here?’ No one said anything. But he knew Bruce didn’t smoke, so when we got back to Miami, Yarborough told me to report the next morning at 8 am. He didn’t say why, but I knew. He ran my butt off that morning. The next year, we’re up in Jacksonville again and on the train going up, Yarborough comes up to me. ‘Oakley,’ he said, ‘I had a dream last night. I dreamed that I walked into your room and caught you smoking.’ I said, ‘Coach, that wasn’t a dream, that was a nightmare.’”16

Drinking, naturally, was forbidden. According to Bruce Smith, Yarborough made it seem that just one drink made you a drunkard. Yarborough also tried, with less success, to keep a handle on his players’ relationships with the fairer sex, even though dates usually consisted of innocent trips downtown, sometimes on bikes. When his players flirted with girls in the courtyards after school, he’d tell them, “Stop seeing those gulls,” in his South Carolina drawl. Autrey said he got the first sex lecture of his life from Yarborough. “He’d start off by telling us we’d be better off by not fooling around,” Autrey recollected.17

Not many of the Stingarees had steady girlfriends, but Levin Rollins and Harvey Comfort were the exceptions. They both ended up marrying their younger high school sweethearts. Comfort remembered how he fell for Jeanne Shaffer when she sang for him. “I liked what I saw,” Comfort said with a laugh. “When you were on the Miami High football team, that was something. It paid with the girls.” There were a few other privileges, as well. They could, for example, work in the cafeteria and lunch for free. But that meant they had to work. No one loafed.

Likewise, Yarborough’s practices were no picnic. In 1939, his home was about a mile from the Stingarees’ spacious practice field behind the school. When the wind was right, his family could hear his booming voice barking instructions with the occasional admonition. If a player got out of line or messed up an assignment, he’d get a swift boot in the backside. To play football in Miami, a player had to be in shape. Yarborough made sure of that. He took wind sprints one step further. Each player had to pair up with someone his size. He would put his partner on his shoulders and run the 120-yard length of the field. Then he’d climb onto his partner’s shoulders for the return trip.

He also had a way of thinning out the herd. In The Stingaree Century, Kleinberg recounts Autrey’s typical experience after going out for football. With only so many practice uniforms to go around, the newcomers dressed in shorts, held blocking dummies and observed. Several quit out of boredom. “If you stood there long enough,” Autry said, “Yarborough would say: ‘Go ahead, son, go get a uniform.’”18 That was just the beginning of it. Every newbee would be thrown onto defense to see if they could stand up to the pounding.

If you made it, though, there was nothing like being a Stingaree.

“No one had it better than us. We were surrounded by class people with first-class facilities. Everything was top drawer,” Comfort said. “I got everything I ever wanted out of it.”

Well, almost, anyway.