Jesse Yarborough had just finished riding herd on his team through another scalding September practice session. A cap perched on his head. He tugged at the towel draped around his neck. He was bare-chested for effect, even though his Clemson lineman’s physique had slipped south a tad.

He headed off the big practice field toward his office, satisfied with the day’s work. The newspapermen had emerged from the sparse shade of a few stray palm trees and trailed him, eager to scribble down the “Colonel’s” take on the upcoming 1938 season. He was obliging, or, more accurately, charming them. As he spun his words, exhausted players, trying not to look so, participated in the day’s final ritual across the field from the interview scrum. Yarborough had left it to assistant coach Clyde Crabtree to put the squad through those universally despised wind-sprints designed to sap any little remaining energy from burning legs and aching lungs. It’s how the Stingarees developed their immunity to the heat and humidity as visiting teams hit their thresholds of tolerance. Fight through the urge to quit. Make ’em think you enjoy it.

Suddenly, Yarborough halted an answer in mid-sentence and wheeled around, letting go a rebel yell of a shriek that announced to all he wasn’t pleased with those infernal wind sprints. A “wild yell ripping the quiet afternoon,” Jack Bell called it.

He turned back with a sly smile and a wink.

“You gotta let ’em know you’re watching them all the time,” he told the newsmen.

“But you weren’t,” Bell protested.

“Shhh. Not so loud,” Yarborough chortled. “I make ’em think I can see with my ears.”1

The performance was directed as much to the reporters as it was to his players. Yarborough knew how to make an impression, and he wanted them to know that nothing could escape his attention this year, and that this team, perhaps his best ever, was all-in. What Yarborough saw, he liked. There was size and there was depth. “I don’t reckon we’ll play a game this year we don’t think—before it starts—we’ll win,” he cracked.

The reporters wanted more. He gave it to them. Heck, he said, he had to actually take it easy on his players for their own good.

“We don’t scrimmage more than two or three times a week; those kids are so big and tough and hit each other so hard I’m afraid we’ll be crippled before the season starts,” he chuffed.2

They laughed at the homespun hyperbole and spread the narrative. Lefty Schemer had graduated, but Yarborough still had talent on every unit. Ever since 80 candidates turned out for spring practice, he was over the Miami moon about his team’s prospects. In interview after interview, he was as contentedly confident as if he were relaxing back home watching the cows graze on the family farm in Chester. At least that is how the Miami News’ Luther Voltz had described him when he found him alone in his office that August:

Col. Jesse Hardin Yarborough is quite complacent these days. He lolls in a big chair, his feet propped on a table and munches on a bushel of peanuts, boiled South Carolina style, figuring all is right with the world.

The colonel wouldn’t want the boys to hear it but he will confess to his cronies in the sitting-around room at the University Club that his Miami High Stingarees will be very hard to get along with on the football field this fall. To use an oft-uttered phrase: The colonel’s got ’em.3

He had them all right, especially along the line, the foundation of any great team. Burly All-State guard Joe Sansone, with his pile-driving legs, 200-pound Gene Ellenson, rated among the best tackles in Florida, and Joe Crum, at end, anchored an experienced front wall while Jay Kendrick, a young Samson, was ready for a breakout year. The backfield was loaded as well. Captain Johnny Reid was back to call the signals with Davey Eldredge, the best of the runners, Jason Koesy, the best of the passers and Reddic Harris and Roy Bass, the best of the blockers. Eldredge was to alternate with Oscar Dubriel, who performed admirably in ’37 after being plucked out of gym class. Alwin Carter, who had performed so well after Eldredge was injured, was yet another option.

There was plenty of competition, a coach’s best friend. Yarborough could always use demotion from the starting lineup as a powerful motivating factor. On the line, Doug Craven, Levin Rollins and Gilbert Wilson were showing plenty of promise. In the backfield, J.B. Moore was looking like a find. So was a tenth-grader by the name of Harvey Comfort, who impressed Yarborough in spring practice. And, if that weren’t enough, two new players with varsity experience transferred to Miami High: Roy Maupin, an end from Marist High in Atlanta, and redheaded Bobby Mathews from Sylacauga, Alabama.

When the Miami Herald previewed the season, Luther Evans looked to FDR’s festive 1932 campaign song for his lead:

“Happy Days”

That’s the theme song out at Miami High where the Stingarees, although facing the Southland’s toughest schedule, from Goldie Goldstein, executive manager, to Coach Jesse Yarborough are confident they’ll tackle the opposition with the best all-around club ever to represent the Blue and Gold.

For even Yarborough, who usually carries a face as stern as a Puritan father, can’t keep a cheerful grin from creeping across his pan when he watches his charges hustle in practice.4

As usual, the Stingarees were thinking national championship if they could get through their 10-game schedule undefeated, a daunting but seemingly-doable challenge that would begin immediately.

Knoxville: Fumbling One Away

The first game was against Knoxville, the team that proclaimed itself national champion after dealing the Stingarees a 25-0 defeat the previous year. This time, the game was on the road and, after two straight home defeats against Knoxville, the Stingarees were determined to repay the debt. Yarborough boarded an Eastern Airlines plane to Tennessee (the athletic department’s budget was that impressive) to scout the Trojans’ 31-0 win against outmatched Bradley County. He found them formidable, despite the loss of seven starters, including Johnny Butler, now doing his running across town for the Tennessee Vols’ freshman team.

Yarborough caught up to Knoxville coach Wilson Collins on the field afterwards and marveled, “Why, they look even bigger than they did last year, Wilson.”

“They aren’t so big,” Collins replied. “Those shoulder pads just make them appear larger than they really are.”5

Suitably impressed, but armed with information, Yarborough got back to Miami in time to see his B team take on Fort Lauderdale’s varsity. The game, while it wouldn’t count on Miami’s record, offered some basis of comparison, given that the Flying L’s had played a 12-12 tie with Bradley County, the team Yarborough witnessed Knoxville destroy. And it wasn’t exactly a B team that Yarborough was fielding. The backfield featured Eldredge and Dubriel. The line had varsity first-teamers Kendrick and Butch Miles. That the Stingarees could manage just a 13-13 tie was rather curious. Just as curious—and costly—was Yarborough’s decision to play Miles, who broke his collarbone, the second of two setbacks leading up to the Knoxville game. The first occurred the previous Wednesday when Alwin Carter was declared academically ineligible. Koesy, too, was now nursing a bruised knee. Yarborough’s “Puritan” visage returned as he considered ways to reshuffle his lineup.

The road trip, in any case, was a fantastic one for a team unaccustomed to making them, and there was no shortage of fanfare at the sendoff. The marching band was out on the platform at the Seaboard station in Allapattah where 24 players boarded the train Wednesday night. Coeds waved pennants, cheerleaders went through the team cheers and everyone expected the Stings to return home with a win. Yarborough even turned to a fan before he climbed on board. “Bet on my kids if you’re going to put any money on the game,” he winked, pre-dating Joe Namath’s Miami Super Bowl guarantee by a little over 30 years.6

After Collins’ Knoxville team had been fêted on its trips to Miami, he planned to show the visitors a “grand time” with a program that seemed to steal every minute of the Stings’ time. They arrived on the L&N Railway around 11:00 Thursday night and were whisked to the landmark Hotel Farragut for a good night’s sleep. The morning of the game began with a special chapel program at Knoxville High. They had planned to take a quick tour of Smokey Mountain National Park but Yarborough called it off, preferring to postpone the hoopla until after the fray.

A dance was scheduled for that night and a visit to two-year-old Norris Dam, the first major project of the Tennessee Valley Authority, was scheduled for Saturday morning. That afternoon, the team would take in the Saturday game at Shields-Watkins Field between Clemson, their coach’s alma mater, and the powerful Tennessee Volunteers of Major (not yet General) Bob Neyland. Even Knoxville’s stores greeted the Floridians in style. Merchants trimmed their shops in Miami colors. Woodruff’s appliance store on Gary Street, flashed a “WELCOME MIAMI STINGAREES” message in its ad in the Knoxville News-Sentinel for the Bendix Home Laundry, the first automatic washing machine ever made. The modern marvel, it said, “does all the disagreeable work without attention. Bendix washes the clothes, gives them three separate fresh water rinses, spins them damp-dry, then shuts off … all automatically.”

Why, a housewife’s hands never touches water and the clothes come out “ready for the line.” Unfortunately, the automatic dryer had yet to be invented.7

“The welcome extended by the people of Knoxville and East Tennessee may have to make up for our welcome on the field,” Collins said sheepishly. “Frankly, I doubt that we shall give them as close a game as they are expecting since the Stingarees outweigh us so badly. Their experience, too, is going to tell, but maybe it will be a game they can enjoy.”8

They did not enjoy it.

The Stingarees lived up to their pre-game expectations by outgaining the hosts, 174-39. They were not expected to lose seven fumbles and have two punts blocked. Knoxville’s 19-7 victory even had News-Sentinel correspondent Harold Harris writing apologetically, “Knoxville fans agreed that, but for the breaks which went against them, the powerful Stingarees would surely have won.”9

Collins called the Miami line the hardest charging his team had faced in some time. He said the Stingaree backs were hard to stop. That is, of course, when they weren’t stopping themselves by dropping the ball. At first, Knoxville took advantage of field position to open the scoring in the second quarter, marching just 28 yards after Reid’s punt went out of bounds. Miami’s line failed to stop Joe Fritz on third down from the one and it was 7-0. The Stingarees appeared to have survived a blocked punt when they took over on downs at their five-yard line. But Eldredge, who had his problems holding onto the football as a sophomore, fumbled on the first play from scrimmage. That turned into a 13-0 deficit when Tiger Roberts scored for Knoxville from the one.

Eldredge began to compensate for his mistake in the fourth quarter. Alternating passes with shifty runs, he sparked a long, steady drive and scored standing up on an off-tackle play from the 10. He was fielding a punt later in the quarter with Miami within a touchdown. But Fritts launched the kick high into the lights at Caswell Field and Eldredge lost sight of it. It bounced off him at the 25 and rolled all the way to the five where the Trojans recovered again. A second Fritts touchdown clinched the Knoxville win. Eldredge left the field in a bad mood. He just couldn’t cure himself of his bout with of fumbleitis.

“Breaks are part of the game,” Yarborough said. “Knoxville played a fine game and by their heads-up play they deserved to win.”10

Robert E. Lee: There Goes Florida

Yarborough played down the defeat, even though it just about killed any chance for a mythical Southern championship. It could easily be rationalized. It was Miami’s first game, Knoxville’s third. Even the inimitable Neyland and Clemson coach Jess Neeley, who scouted the game for potential talent, had been impressed by the Stingarees, calling Miami’s line the speediest high school unit they’d ever seen. Just clean up the turnovers and all would be fine. The Stings historically rebounded strongly after defeats, which Miamians expected them to do yet again. After all, that next game was at home against a Florida foe, Robert E. Lee of Jacksonville, and the Stingarees hadn’t lost to an in-state school in 10 years.

The Generals, though, had not been pushovers. They had stayed within a touchdown of Miami the three previous years, including the ’37 mud bath, and they weren’t heading down the Florida East Coast Railway as any sort of get-well gift. They had rolled over their first two opponents by a combined 74-0 score. The Florida Times-Union wrote they were bringing a “now-or-never attitude” to the game, confident, the paper said, that “they’ll be the ones to hand the Miamians their first defeat at the hands of a Florida rival since 1928.”11

Crabtree vouched for Lee’s strength. He scouted the Generals’ 33-0 rout of Gainesville on the way to Knoxville and, when he caught up to the team, he brought ominous reviews. Lee’s line was small but quick, he reported, and 186-pound Maxwell Partin, who shifted between end and tailback, was exceptional, a worthy successor to the slippery Dingman.

The practices were hard, despite the Stings’ added injury problems with center Peter Schaefer out with a knee injury (Kendrick would be shifted to his spot) and Crum hobbled but available. Old “Cannonball” Crabtree suited up to impersonate Partin against the first team defense and had a field day getting around the ends.

“That’s what you can expect Saturday,” the former Florida flash told them. “And this Partin is faster than I am.”12

Aside from stopping Partin, Yarborough’s biggest problem was Eldredge. His was fleet-footed and impossibly agile. But, his hands? He just couldn’t stop fumbling the football. Even in practice. With Dubriel looking sharp, Yarborough made the decision. Dubriel would start. Eldredge would come into the game as a substitute. For a kid as competitive as Eldredge, it stung like a Miami sunburn.

In spite of the issues, Yarborough sounded confident: “Tell ’em we’re going to war out there,” he blustered in the Jacksonville paper.13 But did he mean it? The visitors did. Conditions were perfect for the 3:30 kickoff at Burdine Stadium. The Stingarees were not. Eldredge and Company fumbled seven more times, losing four of them. This time, the turnovers didn’t lead to points. They just allowed the Generals to control the game. Partin was as hard to corral as Crabtree had been in practice. In the first half, playing end, he gained some nice yardage on a couple of reverses. In the second half, at tailback, he set up and scored the game’s only touchdown. The vaunted Miami line was outplayed. The quicker Generals set them up on trap plays and Partin ran through some big holes. Miami’s offense was no better. Lee’s front stuffed the running game.

It wasn’t until after Partin’s third-quarter score that the now-desperate Stingarees showed any life. After stopping Lee on their 12-yard line, Yarborough sent Koesy into the game late and he completed pass after pass, mostly to Reid. Miami was at the Generals’ 29 with time enough for one last play, trailing 6-0. Eldredge worked his way out of the backfield and was at the one-yard line with his back to the goal when Koesy let loose a pass that could have tied the game.

The crowd of 3,300 stood and watched the ball hang in the air. But Eldredge, perhaps thinking about the move he’d have to make to score, failed to secure the ball and the game was over when the ball hit the grass. The Stingarees were 0-2 and Eldredge was marked with butterfingers. It wasn’t supposed to be this way.

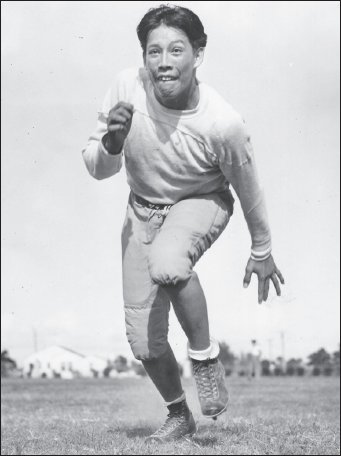

Mike Osceola rushes upfield in a staged publicity shot. Courtesy Estate of Mike Osceola.

Miami hadn’t lost to a Florida team since Thanksgiving Day, 1928, when Lakeland came down from Central Florida and won by a 13-7 score. In all probability, the Stingarees, who had fumbled away the Southern championship in Knoxville, had lost their long-held claim on the state championship, unless Lee fell apart—and that didn’t seem likely. In two games, the entire season outlook changed. No, things were hardly as merry on the practice field as when Yarborough bantered with the writers before the season. First, the fumbling needed to stop. Crabtree went over films of the Lee game and was certain he found the problem when he called his backs into the room.

“Our backs were trying too hard to fight for yardage after they were tackled,” he explained. “Instead of relaxing and covering up when it was certain that they would be downed, they kept squirming and inviting second and third defensive players to hit them and the shock was just too great. One of the boys (presumably Eldredge) was trying to change the ball to the arm away from the tackler just as he was hit but I don’t think he will be doing it any more.”14

Yarborough entered the darkened room and interrupted the film session with a special announcement. Anyone who fumbled in the next game against Nashville Central would take an immediate seat on the bench. He also planned one change in the lineup with Charlie Burrus making his first start as the blocking back. Eldredge was starting the game on the sidelines.

As for his underachieving line, changes were coming, one by necessity with Ellenson spraining his ankle. To underscore the point, Yarborough was starting at one tackle his personal project, the sophomore Seminole Larry “Mike” Osceola, who had played in just one game before in his life. At the other tackle, Dick Fauth was coming up from the B Team after Roy Risgby, who started for the injured Schaefer against Lee, was benched for poor play. Crum, who played crummy against Lee, was to start the game on the bench behind Damon Bates. Even Jack Bell called out Crum in the paper.

“If Joe Crum doesn’t snap out of it and play better ball than he did last week he’s due for a kick in the pants from us truly,” he wrote.15

Miamians were justifiably angry over the team’s performance. The Stingarees had not been 0-2 since 1924. In fact, it was the only other time a Miami team ever had a losing record at any point in the season. Its worst overall record was 5-5, in 1936.

Nashville Central: Back on Track

Fortunately for the Stings, Nashville Central wasn’t arriving as a powerhouse. Yarborough put Central on the schedule after it finished as runner-up for its city title in 1937. But with only two returning starters and 10 lettermen, Central came into Miami on a two-game losing streak after starting off with a pair of wins. A fed-up Yarborough put the Stingarees through a few hard practices. The visitors were going to catch the Stingarees at the wrong time. It all worked in Miami’s favor, even Yarborough’s promise to yank the first man who fumbled out of the game. Sure enough, Reddic Harris fumbled three plays after the opening kickoff, and that gave Eldredge his chance to get back on the field. In fact, the officials had barely finished pulling players off the pile before Eldredge was sprinting onto the field to play defense past the dejected Harris as he hung his head.

Li’l Davey didn’t disappoint. The first time he touched the ball on one of those punt receptions he’d been fumbling, he brought the ball back to Miami’s 48. Here, Yarborough’s new line configuration opened a huge gap on the right side. Osceola cleared his man, and Eldredge zipped around him, never to be touched en route to a 58-yard touchdown. That was one way to avoid fumbling. Never let them catch you.

Luther Evans of the Miami Herald was thrilled.

“Zigging and zagging, the Stingaree speed merchant baffled the frantic backs and toyed with the safety man to go across the goal, slightly tired but unmarked after running 58 three-footers,” he wrote.16

Eldredge repeated the feat twice more, from 18 yards out and from 48, with all three of his TDs behind the blocks of Osceola, who had an entire cheering section on hand from the Seminole tribe. It was 25-0 at halftime when Yarborough called off the dogs and played his reserves in the entire second half. The 25-7 victory certainly took the pressure off the team and, specifically, its star running back. The Miami News called the game a “personal triumph” for Eldredge.17

It was just the beginning. Yarborough alertly changed the emphasis from power to speed, utilizing outside runs and quick openers. It takes a great coach and the right talent to pull that off, but Miami soon hit its stride. Eldredge, finally free of worry about fumbling, began to run less tentatively. The offensive line, which returned the injured Ellensen and Schaefer at tackle, became more versatile and, with Osceola emerging, deeper than ever.

Savannah: Davey’s Torch Dance

Winless Savannah was next to visit Miami that Friday night, but the Blue Jackets were doomed from the start. The stage was set for a crowd-pleasing show at Burdine Stadium, including halftime, which Earnie Seiler would have been proud to produce. Frances Mary Walker, Miami High’s “shapely 16-year-old drum major,” led the band out while twirling a flaming torch. The crowd loved it when the stadium lights were extinguished to “make the spectacle more impressive.”18

Miss Walker was almost the biggest hit of the night. Almost. Eldredge was the main attraction. The papers now began to give him star billing again. With his socks rolled down above his high-tops, his chinstrap tight under his jaw, Eldredge looked every bit the football hero. His white jersey with the satiny-gold numerals shined in the Orange Bowl lights as brightly as Miss Walker’s torch.

The Miami News said Eldredge was in his “best form,” that he “ran with all the finesse of a great back. He was fast, had a sweet change of pace, and followed his interference and when finally on his own he was a hard hombre to render horizontal.”19

“Li’l David has winged feet and Lawd, Lawd, how he can run,” raved Miami Herald sports editor Everett Clay.20

Today, a 14-0 final score may not seem like a rout. This was. At least it was written up that way. And it happened as quickly as the churning of Eldredge’s legs. Both touchdowns came in the first half before Yarborough emptied his bench. After Koesy and Burrus combined for a 21-yard pass completion to the Savannah 12, Eldredge darted around a block by Harris and was across the goal line almost before the visitors could react. Harris scored the second touchdown after Eldredge brought the crowd to its feet with a few more dazzling runs. Kendrick almost single-handedly shut down the Blue Jacket running game inside. Said the News:

So neatly did everything work that Savannah appeared bewildered and did nothing soon thereafter to dispel such belief.21

Andrew Jackson: Partial Payback

The Stingarees’ 0-2 start had nearly been forgotten along with Eldredge’s fumble problems and the next week’s game provided some measure of revenge. It was the second of Miami’s two 1938 road trips, this time to Jacksonville to play Andrew Jackson and it was a chance to atone somewhat for the loss to Jacksonville’s other high school, Robert E. Lee. What’s more, Jackson was 3-1-1 in four contests and would play Lee later in the year. An impressive Stingaree win, combined with a Jackson win over Lee, could allow Miami to claim another state championship.

The Stingarees and Tigers had not played since their post-season meeting on New Year’s Day, 1935, a Kiwanis charity game with the state championship at stake. Miami, which was twice tied and once-beaten that year, handed Jackson its only loss of the year, 7-6, when Norman Pate, the Stingarees’ All-Southern quarterback, called for a pass on fourth-and-four from the Miami 44 and completed it to keep the winning touchdown drive going. Eldredge’s brother Knox sent a perfect drop kick through for the point-after to give the “gallant” Stings the much-lauded victory.

“For five years I’ve been trying to get them to play us,” explained Yarborough, back in sardonic humor. “But they have always turned thumbs down on the idea before this year. Gee! They must have a great team or they wouldn’t be playing us at all.”22

Before turning his full attention to Jackson, though, Yarborough had one other matter. His B Team was traveling to take on Fort Myers Junior High, a game that oddly turned into one of the most important of the year. The JV Stings blasted their younger opponents, 40-0, but that wasn’t the point. Harvey Comfort, who first impressed during intramurals, then in spring practice, did everything for Miami. He showed what the Fort Myers News-Press called “shifty speed” in running for two scores and showed off his arm to JV coach Pete Tulley by throwing for two long TD strikes to Bucket Barnes and J.B. Moore, both of whom would start on the 1939 team. Tulley brought back such glowing reports that Yarborough immediately promoted Comfort to the varsity and made him part of the 30-player party headed to Jacksonville.23

Comfort didn’t get into the varsity game in Jacksonville. After all, he hadn’t practiced with the big squad all year. But he did stand closely by Yarborough to watch and learn. The Stingarees won, 12-7, in a hard-fought battle witnessed by 5,000 fans. The home team held Eldredge relatively in check, limiting him to 65 yards, but Reid took over as the featured attraction by throwing one TD pass to the revitalized Crum before taking it over from the one-yard line for Miami’s second score. It was Miami’s first win over a winning team and lifted the Stings over .500, where they would stay the rest of the season.

Lanier: Poetic Justice

Miami was off the next week as Sea Biscuit and War Admiral dueled in their historic match race at Pimlico that Tuesday. That gave Yarborough time to plan a new look for the next opponent, Lanier of Macon, on Armistice Night. Injury-riddled Lanier was 0-4-3 and had scored just 13 points all season. But Selby Buck’s team had won the Georgia state title and bullied the Stingarees a year earlier. The Maconites and Knoxville were the only two teams to hold advantages over Miami in their all-time series, and the Stingarees were hungry for payback. Yarborough also figured it was the perfect time to give Comfort his first start with an extra week of practice against a weaker opponent.

Comfort was ecstatic. He knew how rare it was to be promoted from the B team, and he didn’t miss his opening during the off week by excelling in a series of hard scrimmages, proving he could play with the big boys. Yarborough and Crabtree delighted in Comfort’s unique running style, low to the ground and with power. And he didn’t fumble. And Comfort wouldn’t be the only Sting making his starting debut against the Poets. He’d run alongside Pericles Nichols, who was also promoted to the starting lineup after an impressive debut on both offense and defense in Jacksonville.

“These backs. Along with Li’l David Eldredge, have begun to show themselves and they’ll be mighty hard to stop Friday night,” Yarborough crowed.24

Yarborough, as they say, had more depth than he knew what to do with. In fact, the Miami News ran a picture the day of the game with three rows of four backs stacked up on each other, smiling from inside their leather helmets. The same could be said for his line. Butch Miles was returning from his broken collarbone, but he couldn’t break into the starting lineup the way Jay Kendrick had been opening holes and clogging the middle.

It was all too much for the Poets. Oscar Dubriel had run back the opening kickoff to the Miami 18-yard line and had barely caught his breath, when he took the direct snap on the first play from scrimmage and followed his blocking around the right end. He turned the corner, shrugged one defender off his hips and romped 72 yards to a score. Then, Eldredge entered the game and, after a punt, made good on his first carry, slipping into the open between right guard and tackle, and sprinting into the end zone on another 72-yard TD run. Lanier was as dazed as a prizefighter stumbling in the ring, but with no referee to call off the brutal pounding. Reid scored three times, and Ellensen blocked a punt for another TD in the 38-6 rout.

The Stingarees were peaking. Yet, there was one problem. Lime burns. Of all the hazards of the football field, the most hazardous was sometimes the field itself. When unslaked or “quick” lime was used to mark the lines, any contact with moisture—rain or even sweat—set off a chemical reaction that could cause, at worst, second-degree burns, sometimes right through the uniform. Precautions weren’t always taken and a careless workman could cause unintended agony. When it happened at a Clemson-Wake Forest game in 1936, Greenville News sports editor Scoop Latimer, Yarborough’s old friend, called it “tantamount to criminal negligence.”25 Nevertheless, instances of quick lime burns from football fields persisted into the 1960s.

The grounds crew used such untreated lime for the Lanier game with 12 Miami players developing painful blisters, four of them serious. At first, there were doubts that Joe Sansone, Roy Bass, Kendrick and Crum could play against the high-flying Pine Bluff Zebras, the defending Arkansas state champs. They all ended up making it.

Pine Bluff: No Contest

The game was originally scheduled for Saturday afternoon but was moved under the lights to drive up ticket sales. Pine Bluff’s celebrated passing attack was the top attraction. Coach Allen Dunaway had been throwing it out of a double wing attack since before he coached Don Hutson, among the greatest of all NFL receivers in 1930. Now, he had Hutson’s two brothers, Robert and Raymond, in his backfield. The Stings didn’t face the double wing often, so Yarborough enlisted his predecessor at Miami, Fred Major, to aid the preparations since Major was running the same offense at Ponce de Leon.

The Zebras threw it all right. Everett Payne lofted 33 passes into the night air, completing 13 for 179 yards, with most of them in comeback mode. The Stingarees dominated the lighter visitors in a 33-7 win that included Eldredge’s 96-yard interception return, another highlight reel play, had there been those back then. Eldredge neatly cut in front of the pass at the four and was up to the Pine Bluff 40 before any Zebra had an angle on him. He seemed to be hemmed in at the 29 but cut back and picked up the blocking of Crum and Rigsby and coasted in from there.

Pine Bluff, which would win the Louisiana State Authority’s version of the national championship game the next season, hardly looked the part. Luther Evans closed his game story in the Miami Herald with a derisive kicker:

And now we have seen football as they play it in the Southwest.26

Ouch.

Edison: The Jinx Continues

Now, local fans were going to see how football was played in Miami. The week of the Edison-Miami game had finally arrived and, once again, Cardinal fans were certain this was their year—certain, but still nervous.

The usual back-and-forth banter had actually started before the season. A new state rule prohibited teams from practicing before September 1 (not including spring practice), and both coaches accused each other of breaking it. Pop Parnell admitted there were a few players on his practice field, but it was none of his concern if they wanted to break in new shoes. Colonel Yarborough said there wasn’t a coach in sight when a few of the Stingarees were seen kicking it around.27

Because the University of Miami was playing Bucknell in the Orange Bowl on Thanksgiving Day (the high schools ended up outdrawing the Hurricanes by 3,000 fans), the Edison-Miami grudge match was scheduled for Wednesday night, depriving the teams of sufficient preparation time. The Cardinals, or Red Raiders as they were sometimes called, had won six straight games since being thumped, 14-0, by Jackson of Jacksonville, the only common opponent. In all, Edison was 7-1, Miami 5-2. As usual, the city championship was on the line, as was the privilege of hosting the annual Christmas game on December 26. The Stingarees were 8-5 favorites, although Herald sports editor Everett Clay noted that the “smart boys” were taking Edison with seven points. He had his doubts.

Possibly it is not as much a question of Miami High beating Edison as it is a question of the Red Raiders beating themselves. For the Edisons seem to choke up every time they step on the same football field with Miami High. There is no particular reason for this tension as the Red Raiders are usually the better ball club and figure to win with little trouble. Something always seems to catch the Edison boys in the pit of the stomach when they see those terrible Stingarees rushing down on them.28

Bell, at the rival News, pooh-poohed Clay’s theory—especially the bit about Edison’s historical strength. And, for once, Edison did not quiver at the sight of navy blue and gold. The Red Raiders outplayed Miami. They outfought Miami. They outgained Miami. They did everything … but outscore Miami. If there were anything more frustrating than the previous season’s unexpected rout at Stingaree hands, it was the 6-6 tie that captivated the crowd of 16,647 that night.

Reid got the Stingarees out in front in the opening minutes. On third and four from the Edison 45, he drifted back to his right as Crum sprinted up the south sideline. The Miami captain’s heave pierced through the light beams slanting through the night. With every fan on his or her feet, the ball looped into Crum’s outstretched hands then was clutched to his chest at the 17. Crum, the ex-Edison player who had so delighted in crushing his former team the year before, had seemingly begun another rout as he scampered into the end zone. Even when the Cardinal line smothered what turned out to be the critical extra point try, the Stingaree cheering section remained smug. At that point, it seemed as if the familiar script would play out again.

Instead, they spent most of the remaining play with lumps in their throats, as their team staved off Edison threats. Parnell’s boys marched to the Miami 17, the 20 and the 19 only to be repelled each time, twice by batted-down fourth down passes and a third time by a Harris interception. But Edison, led by triple-threat back Red Bogart, kept battling.

Finally, down to one of their last chances in the fourth quarter, the Red Raiders sustained a drive. Bogart’s passes found their mark, and a halfback, Wallace Seekins, fought his way from the five to the goal line, where the football was knocked loose and fell into the end zone. For once, Edison was spared another heartache. Pahokee Smith, a lineman who played his heart out during the game, pounced on the football to tie the game.

Out came Carleton Lowe, one of the most sure-footed kickers in the state, with a chance to put Edison ahead. But point-after conversions were no sure thing in those days, more like 50-50 propositions at best. Lowe, who was playing despite a dislocated hand, didn’t get enough foot into it and the ball fell short of the cross bar. Later, in the Edison dressing room, Lowe buried his face in a towel and sobbed.

“I guess I flunked out,” he said. “I just wasn’t any good.”29

It could have been worse. Miami summoned up one last drive that ended on the Edison 14 when the big red clock struck zero. Miami’s stunned fans calmed fast-beating hearts. Edison fans stormed the entrance to the locker room to congratulate their team. It was as if the Cardinals had won, only they hadn’t. When Yarborough met Parnell at the middle of the field after the final whistle, he said, “Shake hands with the luckiest guy in town.”

“By Johnnies, I don’t know what to say,” Parnell told the writers. The scribes did. When they got to their typewriters, they sang the praises of Bogart, who ran and passed the Stingarees silly. Wrote Bell:

That 6-6 score goes into the record book but someday we’ll be tellin’ our grandchildren about the night Red Bogart put on the greatest exhibition ever seen in this Miami-Edison football classic. Once in a long time you see a flaming, inspired boy down there leading his team with force that will not be denied. And when you do see such a boy you don’t forget.30

Parnell outcoached Yarborough in this one. Edison’s offense normally operated out of the Notre Dame box but Pop surprised Miami by alternating between the single and double wing. Edison kept attacking off the weak side of the formation, another changeup. The Stingaree line was supposed to have a big advantage, but Parnell played his tackles inside the Miami ends to stuff the middle runs that the Stingarees ran wild with in previous years. That left Edison’s two ends on islands, so to speak, but the gamble paid off.

Of course, it settled nothing, least of all who would host the Christmas game. When the teams had played to a 12-12 tie in 1935, they reached a compromise that sent Miami into the Christmas game on the basis of its stronger overall record and the fact that it had established the classic. Edison would receive 25 percent of the gate receipts. This time, it wasn’t so simple. Clay immediately began to call for the teams to play a Christmas rematch instead of inviting a team from elsewhere:

Forget all this business of an unbeaten, untied, unscored-on Northern high school team and an intersectional game. Miami High and Miami Edison are the teams folks want to see play again, not Miami High and Flap Stop, Ind., or Miami Edison and Mouth Wash, Mass.31

Yarborough suggested playing in two weeks on December 9. Parnell demurred because his team was traveling to Greenwood, Mississippi, for a December 2 game and would be at a disadvantage. Clay persisted in the Sunday editions of the Herald. He included letters supporting his position from Frank B. Walton, president of the Edison student body and Joe Sansone, the Miami guard who was president of the senior class. Below the column he ran a ballot, which was worded to produce his desired outcome. He could have been a modern pollster.

The ballot offered readers two options: to be in favor of Edison and Miami playing off on December 26, or to not play off the tie at all. The option to play the game on an earlier date with the winner hosting an intersectional opponent December 26 was conspicuously absent. Given just the two choices, readership, not unsurprisingly, voted unanimously in favor of a playoff. Clay attended a meeting to decide the matter and spilled the mailed-in ballots onto the table. They ended up filed in the trash. The rematch was scheduled for Wednesday, December 19, a week before Christmas. Yarborough and Parnell would jointly choose the opponent.

Clay was unhappy. He called it a “big mistake.” The decision to play on the 19th, Clay wrote, “completely ignores the wishes of the students of the two schools, as well as everybody else in town.”32

Clay pointed out that Edison, if it won the playoff, would be playing its twelfth game of the season. Miami would be playing its eleventh. That’s too many for high school kids, he argued. But, while Yarborough and Miami Principal W.R. Thomas were amenable to a Christmas rematch, not so Parnell. Edison had never hosted the Christmas game, because it had never defeated Miami. He wanted to give his kids that chance. And, so it was settled, with 40 percent of the proceeds to go to the libraries of both schools, 10 percent to charity and half to feed underprivileged children.

Boys: Shorty Comes up Short

Until then, both teams had big games in a matter of days. For the Stings, it was the Kiwanis-sponsored game against Boys High, their second-best rival. Shorty Doyal was bringing his Purple Hurricanes into their season finale at 7-2-2 with similar results against Knoxville, Savannah and Lanier so the game was rated a toss-up. Perhaps a letdown would have been natural for Miami, caught in between its two games against Edison. But Miami dispatched the Atlantans with surprising ease. Eldredge gained most of the yards and Harris scored all the touchdowns in a 19-0 rout. Edison’s trip to Mississippi produced a 19-19 tie with Greenwood the next night. Then, over the next long 18 days, everyone’s attention turned to the playoff.

Edison: The Grudge Bowl

Yes, everyone’s attention was on the playoff, except for Everett Clay. His focus was riveted on changing the game to Christmas time. In a last-ditch column written for the December 6 editions, Clay cited numerous conflicts that would keep attendance down on December 19. Merchants kept stores open late for Christmas shoppers, and there was a Rachmaninoff concert in the Miami Edison Auditorium. Clay pleaded for school administrators to get involved. It was no use.33 On Thursday of that week, feelers were sent to McKeesport, Pennsylvania, High, Peabody, Massachusetts and East High of Chicago. On Friday, Yarborough and Parnell decided on the Pennsylvanians.

The newspaper ads called it the “Grudge Bowl.”

Edison was a narrow 6-5 favorite. In a way, Miami had the advantage. Edison had caught them by surprise in the first game. Now the Stingarees could scheme for Bogart. “Miami High has the motion pictures of that last game and they’ll be a big help,” Parnell said apprehensively. “They know just how we were running those weak side plays that gained so much ground.”34

Yarborough let on that he was shifting his lineup. Sansone, the All Southern lineman who had played a linebacker, in the first meeting, was moved back to his regular position. Kendrick was moved to tackle. On offense, Comfort was worked in to work spinner plays. Otherwise, both camps were shrouded in secrecy. Rumors of scheme changes and new formations swirled. Word was that Miami was installing new passing plays, and that Parnell had even more surprises in store for Miami.

It all added up to little. The game came down to trench warfare. Outplayed in the first game, Miami’s line, led by Sansone, took over. The rumored new pass plays were unnecessary, as the Stingarees dominated in the running game with 247 yards. And yet, Miami eked out just a 7-6 win on the margin of Shaffer’s extra point on the first TD of the game. Jack Rice took the kick after Edison answered Miami’s first touchdown, yet did no better than Lowe in the first game. Luther Voltz suggested in the Miami News that there was something to the jinx since Edison had scored seven touchdowns in the 16 games and had never converted for the point-after.35

Where Edison deserved a better fate in the first game, Miami was the superior team and deserved this win. “They’re tough when they’re aroused,” an Edison coach told Voltz. “If they would play the football they’re capable of for 60 minutes, there’s not a high school team in America able to stand up against them.”36

McKeesport: A Strange Finale

Pennsylvania’s McKeesport High School would test that theory. The Tigers, a.k.a. the Tubers, were Class AA (large schools) champions of the Western Pennsylvania Interscholastic Athletic League. The city, with a gritty population of over 55,000 at the time, was situated at the confluence of the Monongahela and Youghiogheny Rivers, a suburb of Pittsburgh. The National Tube Works factory employed the majority of residents, and their kids had the built-in toughness to be expected from the sons of steelworkers. They usually followed their fathers to the blast furnaces soon after graduation. The environment quite naturally forged high school football players as its factories did steel girders. Football was—and still is—a religion in Western Pennsylvania, and winning the WPIAL was and still is a massive accomplishment.

McKeesport had lost only to Paul Brown’s powerhouse Massillon in the second game of the season but had not lost to a Pennsylvania opponent in three years. They were led by stocky fullback Casey Ploszay, who had scored 129 points on the season, including three touchdowns in the 38-20 WPIAL championship game win over Johnstown. Ploszay did everything for the Tubers—run, pass and punt.

Just as a few other teams that had come to Miami, McKeesport would not be at full strength. It had to leave behind its sturdy left guard, Richard Stevenson, due to the segregation laws. The Tubers, also like previous visitors, were at another disadvantage. The heat. When McKeesport’s husky cigar-smoking coach, Jack Tinson, stepped off the train, he was wearing an overcoat, suit coat and vest. He quickly stripped them off and wiped his brow.

“Does it stay this hot down here?” he asked. “I’ve been perspiring ever since we crossed the state line.”37

The Miamians shrugged. It was only 75 degrees. The city was in the midst of a cold snap. But Tinson had a point. His team was hardly able to practice because of snow storms in Pennsylvania. He would try to whip them into shape in three days’ time, but he couldn’t push them too far.

The Stingarees had been working hard in what seemed like cool conditions. Yarborough put them through three strenuous scrimmages. The day before the game, he announced his captain and alternate captain for next season in a vote of the team. Davey Eldredge would take over for John Reid and lead the team onto the field. Jay Kendrick would take over for Joe Sansone. They would be the only underclassmen to start the game.

It was, as Jack Bell wrote, a “queer” game.38 Maybe the season was just one game too long. The game drew just 5,490 spectators and the two teams traded mistakes, including the one that gave the Stingarees a 19-13 win, their first in the Christmas series since 1932.

As time wound down, the score was even. Ploszay stood in his own end zone, apparently set to punt. But the play was a fake, a rather knuckle-headed decision. The snap, which was supposed to have gone to the up-back, rolled back to the McKeesport captain, who was aware that, if he couldn’t get out of the end zone, Miami would score a safety. So, with the gold-clad Stingarees closing in on him, Ploszay blindly threw a pass into the air. The duck fell into the hands of Miami tackle Gene Ellerson, a senior who had never touched the football before in his entire high school career. He stumbled inside the one-yard line, and Oscar Dubriel took it in for the win from there.

Eldredge’s debut as Stingaree captain started well when he dashed 55 yards for the first TD of the game in the first quarter. It was just like most of the other big plays he broke off, a sweep around left end, a neat cutback to the center, where he picked up a wall of blockers and an unabated gallop to the end zone with Crum wiping out the last potential tackler with a nasty rolling block.

But Davey was also called on for pass interference to set up the first touchdown and was caught napping on a bullet pass by Ploszay that pulled McKeesport even early in the fourth quarter.

It had been that kind of year for Eldredge, although brilliance mostly outshone the negative, as it did for Miami in general. No, the Stingarees couldn’t claim a national title or even the Southern championship. They barely won the championship of the city. Yet Yarborough called it his best team yet and with all the seniors being lost, he wasn’t sure whether the ’39 team would be able to surpass it.

“That closes just about the greatest season Miami has had in the last 10 years,” Bell wrote.39

Just wait until the next three.