Art Argauer had built a team and won his first state football championship. Now he had to build a program.

He would do it brick by brick, not through domination but rather through grinding. Garfield had come through a tough, but fabulously successful, 1938 season preceded by a harsh and disappointing ’37 campaign. The Boilermakers had followed up a losing season with an undefeated one, but each of those seasons provided important lessons for the veterans of those campaigns.

The competition in New Jersey was stiff, and the criticisms came easily—both prime motivators at persevering not only as a good team, but more importantly, as a team that is good at winning. Recall Miami coach Jesse Yarborough and how, at the start of the 1938 season, he asserted his team would not enter a single game not believing it would win. But Miami was a different case. The Stingarees’ reputation preceded them. They expected to win, because the teams before them won. They would always have believers, in and out of their—and the opponents’—locker rooms. The Garfield players’ belief system was built within the walls of their locker room. Bill Parcells had a saying when he coached the Giants: “Confidence is born of demonstrated ability.” He might have added: “especially under pressure or in the clutch.” By 1939, the Boilermakers went into every game believing they could win no matter what.

“We had complete faith in Coach Argauer, and then there was Benny (Babula),” Walter Young recalled. “I’d say we were a tough-minded team, maybe because we didn’t know any better. It was as if we’d just go out there and play, trusting what we were taught. We didn’t think about it. We just played.”

When 65 candidates greeted Argauer at the first practice, none of them had any inkling of spending Christmas in Miami or playing for a national championship. The Boilermakers would navigate through close calls and narrow escapes until they found themselves in the blinding Florida sunshine. All the while, they summoned an innate ability to persevere, instilled by their coach, hardened by trials even tougher than faced by the 1938 team.

Every opponent was after them. Ever since state champs were first named in 1912, only Rutherford (in 1921-22) and the Bloomfield Bengals (’33-’34, ’36-’37) had repeated, so the odds were against them in the first place. For so long, it had been just a matter of toppling the Bengals. Not in 1939. There were several strong squads with legitimate title aspirations, including those not on the schedule. Unlike Bloomfield, Garfield hadn’t established a mystique. People thought the Boilermakers could be had.

All of this was plain to Argauer, who tempered outside expectations while building inner confidence. Perhaps out of habit, he sang the blues after that first pre-season workout, at which Paul Horowitz of the Newark Evening News scoffed: “Argauer’s pessimism seems to have no foundation.”1 Soon, the coach gave up the charade. Who was he fooling? Not only was his varsity coming off an undefeated 1938 season, but his JV team was as well.

“I know I have a big job ahead but I’m not letting that worry me,” he told the Newark Sunday Call as preseason preparations were being completed. “In the group out for the varsity are many big, strong boys who played on the junior varsity team when it swept aside all opposition last year. Besides, I have many regulars from the state championship team.”2

Benny Babula had grown in size and strength. He weighed 191 pounds now, 17 more than in 1938. At 19, he was more of a man than a boy. With Ted Ciesla graduated, Babula would pick up the rest of the workload that he split the previous year and call all signals. Wally Tabaka and John Orlovsky were also returning from the deep backfield of ’38, although Johnny Sekanics, that season’s freshman flash, became ineligible to play in 1939 due to poor grades. Babula’s power and Sekanics’ speed would have been a dizzying combination, but Argauer was a stickler for making the classroom a priority.

John Grembowitz and Young were back after starting almost every game on the line in ’38. Angelo Miranda, Alex Yoda, Jack Boyle and Bill Wagnecz, who had all seen action the previous year, would join them. So would Joe Tripoli, the giant 210-pound tackle, who had just moved into town to live with his grandparents after starting the previous two seasons for Park Ridge. Pete Yura was moving up from the JV to take over at center and Ed Hintenberger, whose brother had starred for Argauer a few years earlier, looked as though he could break into the lineup at right end. That allowed lanky 6-footer Ray Butts, a starter at end for four games in ’38, to move to the backfield to add his blocking prowess—with Grembowitz also available for emergency duty there.

Argauer lamented his depth. It wasn’t at 1938 levels, and it showed in the annual pre-season scrimmage against Columbia. The first string, even with Babula on the sidelines with a sore leg, put together a couple of 70-yard scoring drives, but the subs stalled. Later, Babula showed off his throwing arm in a non-contact scrimmage, completing nine straight passes against a Columbia defense that knew he was passing. Columbia coach Phil Marvel marveled indeed, calling Babula, “the best pitcher in football I’ve ever seen.”3

Garfield, the papers said, would be going to the air more often and with greater effect. That was one big area of improvement.

There was one change on the coaching staff. Andy Kmetz left after the 1938 season to take the head coaching job at Hasbrouck Heights. He was replaced by John Hollis, a star on the 1925 team beginning a 38-year tenure at the school. The schedule was stronger from a Colliton-System standpoint with just one key change. Argauer added Thomas Jefferson of Elizabeth, which had challenged Garfield’s state supremacy through much of the 1938 season, in place of smaller Carteret. An undefeated season would not guarantee Garfield another state title—other teams had slightly stronger schedules according to Colliton—but it would put the Boilermakers above most others.

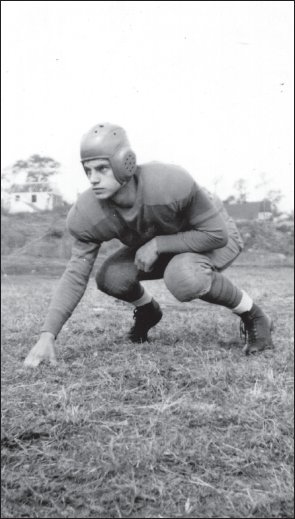

Walter Young gets into a stance for his preseason publicity shot at Belmont Oval. Courtesy Estate of Walter Young

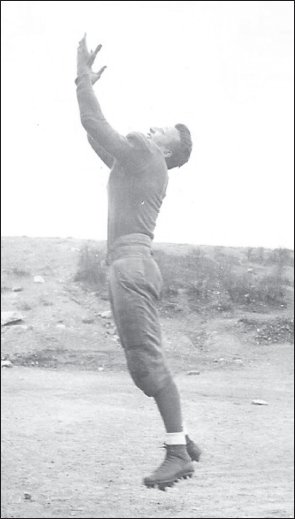

Ray Butts goes up for a pass at a preseason practice session at rocky Belmont Oval. Courtesy Estate of Jack Boyle.

Dickinson: Domination

Dickinson was the first to test the defending champs in the traditional season opener at Passaic Stadium. The Jersey City boys were supposed to be weak on offense, strong on defense, and they were missing two injured starters. Unlike the nail-biting 1938 meeting, however, no one was pointing out any Garfield weaknesses when the game was over.

While Al Del Greco derided Dickinson as “big and fat and greatly overrated” Garfield took full advantage, and 7,000 spectators could vouch for the Boilermakers’ strength.4 Everyone was expecting a smooth ride to another state title after the 33-0 victory, bigger than any recorded by the 1938 (20-0 over Carteret). It was the most lopsided win since the Boilermakers defeated overmatched St. Cecilia by the same 33-0 score in the final game of the 1936 season.

No sooner had those lucky fans settled into their bleacher seats than the rout began. As expected, the Boilermakers started throwing early, as two straight hook-and-lateral plays moved the ball to Dickinson’s 45. Babula gained 43 yards on a couple of off-tackle smashes, and then went over from the two for a TD. In six snaps, Garfield travelled 70 yards. The Hilltoppers were star-struck.

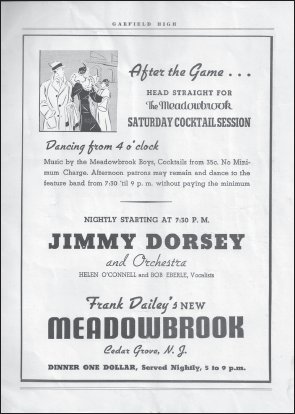

The inside back cover of the Garfield-Dickinson game program invites fans to drive over to Frank Dailey’s Meadowbrook to dance to Jimmy Dorsey’s orchestra after the game.

In all, Babula ran for 92 yards and two TDs and completed 7-of-11 passes with one TD. One scout told Del Greco: “No little guy on any team will drag down that Benny Babula. It takes a big, strong man. That means three of the opponents must slap him down.”5 Garfield’s line held the visitors to 25 yards rushing. What’s more, Argauer’s fears about his depth proved to be unfounded. He substituted liberally, using his regulars only in the first and fourth quarters, and never lost momentum.

“It will take an unprecedented string of injuries to stop Garfield High School from retaining its state football championship this year,” noted the Bergen Record. “The team is banked three deep with unlimited power in reserve.”6

Charles Witkowski seconded that thought. He called the ’39 Boilermakers the best drilled team he’d ever seen in a season opener and rated them over the ’38 champs.

There was one skeptic (the usual one): Passaic coach Ray Pickett. He scouted the game and was confident he could shut down the Boilermakers, at least through the air. He’d get that chance in two weeks. First, it was Irvington’s turn. The Camptowners would provide Garfield with the first test of wills when they hosted the Boilermakers at cozy Morrell Field.

Irvington: Survival

Irvington had opened the season as impressively as Garfield, with a 26-0 win over Thomas Jefferson. The Jeffs, as it turned out, were not even close to their 1938 form but few guessed it at the time, given coach Frank Kirkleski’s sterling reputation. He wasn’t accustomed to losing big.

In any case, Irvington knew this was its chance to muscle its way to the front line as state title contenders and it could not have been more motivated. The Camptowners (Camptown was the original name of the Newark suburb) had no fear of the Boilermakers. They knew they had come close to pulling off a late comeback win the year before. They were always a challenge due to Coach Bill Matthews’ unorthodox offensive formation, with an unbalanced line to one side and an unbalanced backfield to the other. They were as deceptive a team as Garfield ever played. Garfield had seen it before, of course, but playing Irvington always required a sharp week of practice and certain adjustments. The Boilermakers had not reacted well to it in the 1938 game with Irvington gaining plenty of yardage on trap plays and smashes up the middle by Polish pals, Hank Przybylowski and Johnny Kulikowski, the “Flying Skis.” Both were back.

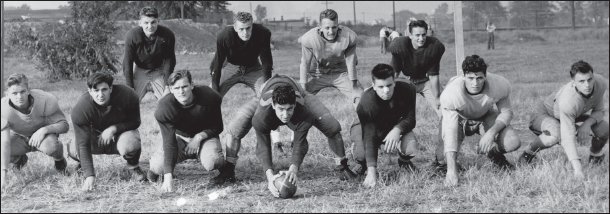

The Garfield line charges in a preseason publicity photo shot at Passaic Stadium. From left to right: Ray Butts, Angelo Miranda, John Grembowitz, Pete Yura, Jack Boyle, Joe Tripoli and Walter Young. Courtesy Estate of Angelo Miranda.

It was another bright, warm day. The shirt-sleeved 8,000 in attendance must have marveled at the intricate maneuvers and booming horns and drums of Irvington’s 132-piece band, then at Babula’s also-booming punts in warmups. He was quite a sight, exploding his thick right leg into the football, lifting off the ground with his left, his outstretched hands held high and his blonde-topped head surveying the results. He sent the ball soaring, some boots carrying 80 yards. Irvington, warming up on the side of the field where those punts rolled out, couldn’t fail to notice. But the Camptowners remained undaunted, even if they had to flip back a few footballs. They planned to force Babula to punt more than a few times.

Irvington started strong. Matthews threw everything at the visitors—half-spinners, reverses and lateral pass plays. There was often no telling which back was taking the direct snap; that’s how well the offense was designed and disguised. The Boilermakers were on their heels on every play as Irvington marched 79 yards for the first TD of the year against Garfield.

Steve Reckenwald, who started the game in place of Przybylowski, hit left tackle for eight yards on the first play, and, as the Camptowners kept the Boilermakers guessing, went off right tackle and into the clear. Babula made a touchdown-saving tackle at midfield. Again, it was Reckenwald for 10 more yards, but he fell to injury and was replaced by Przybylowski. Kulikowski made five yards up the middle and, when it seemed as though Irvington would simply run the Boilermakers into the ground, Przybylowski surprised them with a short pass to Charley Hedden, who raced to the one-yard line, where Wally Tabaka rushed across the field and pushed him out of bounds. The Boilermakers caught their breath and stopped one play cold. But, on the next, Kulikowski went off tackle for the touchdown. Importantly, Garfield managed to bat down the pass on the conversion try to keep the score 6-0.

Irvington’s confusing offense made the Boilermakers look like 11 blind mice at the snap of the ball. Garfield fans were stunned. Irvington was not “big, fat and overrated” like Dickinson. Winning this one would require not only Babula’s best, but also pulls on the rope from several teammates. Two in particular stood out: Wally Tabaka and John Orlovsky.

The compact but elusive Tabaka took the ensuing kickoff. Garfield fans rose to their feet as he weaved through the open field to give their team great starting field position at its 40. Babula tugged his helmet over his blond locks and immediately called his own number. He hurtled across the line and, as two blue-shirted defenders darted for him, fired his right arm out at them and sent them both to the ground. Partially in the clear now, he picked up a great block by Orlovsky and, as the Garfield fans stood again and shouted, “Go, Benny, Go,” he obliged them, outrunning the last safety man for a 60-yard touchdown, eating up the yards with his gigantic strides. According to Gus Falzer of the Sunday Call, it looked as though he were “travelling in seven-league boots.”7 One play, one touchdown. The Camptowners’ shoulders slumped heavier as Orlovsky converted the place kick. Garfield led, 7-6.

Fans, sitting shoulder-to-shoulder in the late afternoon glare of the sunlight, were witnessing one of the most thrilling and most crucially contested games of the year. The grandstands at Morrell Field were so close to the field it was as if the spectators could feel the heartbeats of the players and the players, the hushed breaths of the spectators.

Now it was Irvington’s turn to respond in a game of thrust and parry. Kulikowski ripped off a big run, but fumbled. Babula threw himself on the ball at Garfield’s 13. Irvington forced a punt but it was unlike the bombs that launched from Babula’s foot in the pre-game. It was a rare misfire, a shank, and Irvington took over 30 yards from another touchdown. Garfield was penalized 15 yards for piling-on to cut that distance in half. Backed up against its end zone, the Boilermakers’ defense got even more aggressive, so Irvington burned them with more deception.

On the next play, Hal Hornish sucked Orlovsky out of position and lateraled to Przybylowski, who found open field and skirted his right end to put the gutty underdogs back up. Again, they failed to tack on the extra point. This time, Kulikowski tried kicking, but his try went wide. The half ended, 12-7, with Irvington on top and Argauer addressing his team in the dusty, stuffy locker room. Tactically, he cautioned them against over-reacting on defense. Motivationally, he reminded them how many comebacks they pulled off last year.

Irvington changed into white jerseys at halftime and, so too, its luck. Tabaka began the second half with another fine kickoff return almost to midfield, and the Boilermakers, playing with what Falzer called “smugness,” pounded their way to the Irvington 18, where the Camptowners gallantly held on fourth down.8

With just more than a quarter to go, Irvington resorted to convention to protect the lead. It played the field position game, hoping to rely on a defense that had deprived Garfield any sustained multi-play drives. Kulikowski got off an excellent quick kick on third down, and the Boilermakers were 67 yards away from the go-ahead touchdown. Now, it was Garfield’s turn to get creative. Babula faked a punt and roared around the right side for 33 yards, before three Irvington players hauled him down at the Camptowner 36. With the home team on its heels, Babula called for Garfield’s pet play, the Naked Reverse, and Orlovsky gained 11 yards for another first down on the 22. Runs by Babula and Orlovsky netted seven as the third quarter ended with Garfield 15 yards from the end zone.

The teams collected themselves as they switched ends of the field. Irvington dug in, but the Garfield line’s strong blocking enabled Babula to chew up seven yards to the eight for another first down. The anxious Camptowners jumped the next snap and were penalized a critical five yards for offside. Falzer described what happened next:

A young man answering to the name of Nickolopoulos was sent in to brace the Irvington line at the center. While he stood there in defiant attitude Mr. Babula paraded around the right end and scored.9

It wasn’t exactly a parade until Babula had shaken off an Irvington defender behind the line of scrimmage. One man hardly ever took down the determined Babula. Orlovsky continued his great day by adding the extra point. Garfield regained the lead, but Irvington had one last chance and was determined to make it count. The kickoff went out of bounds, so Irvington started at its 35 and Kulikowski started hitting the center of the Garfield line like a wrecking ball. A series of line bucks and a couple of pass plays put Irvington at the Garfield 20 with all the momentum on its side. Garfield was barely hanging on. The 8,000 could sense an upset in the making when, on third down, Kulikowski burst through the middle one more time to the 10.

But, as Kulikowski pulled himself up, there it was. A yellow flag. As Joe Lovas of The Herald-News put it, “eagle eye” umpire Frank Spotts had “spotted” a hold by Irvington’s left tackle, Hal Arnold.10 Home fans groaned as the yardage was marched off to the 35. On third-and-25, Irvington had to abandon the ground game that had advanced the ball deep into Garfield territory. The Camptowners completed two passes but came up short of the first down and Garfield managed to run the last two minutes off the clock. Two exhausted teams left the field, one in relief, the other in despair. The Sunday Call ran a picture of an utterly dejected Matthews, whose boys had done everything but win. Falzer empathized:

The team in gold held to its two-point lead for dear life up to the final whistle. You could have knocked the Irvington boys down with a crowbar, such was their chagrin, when defeat was their potion after they had come within 10 yards of conquering the state champions.11

It would have been easy to chalk up the close call to Garfield’s overconfidence. It wasn’t. Irvington was good, tricky and inspired. It was easily the best game the Camptowners played all year. They finished with a 5-2-2 record, falling to an upset by Kearny with two scoreless ties against Bloomfield and a good Newark West Side team, eighth in the state in the final Colliton point standings. But that’s the danger the Boilermakers faced every week—that an inspired opponent would elevate its game against them. But winning those games also had its benefits, as Art McMahon of The Herald-News noted.

Garfield’s close rub at Irvington may encourage future Boilermaker opponents or discourage them, depending on how they prefer to accept the narrow squeak. One school will accept the 14-12 victory as proof that Garfield can be beaten when a robust offense is thrown into its teeth.

The other and more logical school will recognize the fact that the Boilermakers beat one of the outstanding clubs of the state in Irvington and did it the hard way—by coming from behind. Pre-season dope conceded only two teams had much chance to upset Garfield. Irvington was one and Passaic the other.

Irvington had its chance Saturday and missed by the space of a 15-yard penalty for holding. Passaic gets its opportunity this week and the Indians have a world of followers who think Ray Pickett’s club has the tools necessary to manufacture a victory. The Passaic-Garfield series has seldom produced a margin larger than a single touchdown and when games are that close they belong to anybody right until the final peep of the whistle.12

Yes, Passaic was next. And it was anybody’s game.

Passaic: Pickett’s Charge

Like Irvington, Passaic could have a clear path to the state championship if it could pull off an upset. As Irvington before them, Passaic went into the Garfield game off an impressive win, 31-6, albeit over a mediocre Clifton team. As usual, Pickett was talking up his team’s chances, although with not quite the same verve as in 1938. Inwardly, he still lamented how two of his backfield starters were knocked out of that game and how he was forced to play an inexperienced line in Passaic’s first game of the season. He had been spoiling for a rematch, but didn’t get it. So, here was another chance against the gold-clad rivals from across the river.

While Picket had complained before the ’38 contest that his team hadn’t yet played a game, he nevertheless believed Garfield had a scheduling advantage this time.

“Saturday’s results were bad for us,” he griped. “Garfield had a tough game and must realize that it has some weakness and can’t get careless. We had an easy game and Garfield now knows we are strong. If Garfield had had an easy game and we had a tough one, it would have improved our chances.”13

That was debatable. Argauer and the Boilermakers weren’t likely to take any Passaic team lightly, especially since they knew how competitive the last game was. Both coaches soon reverted to a more cautiously optimistic tenor.

“Garfield has a tough club but if (Nick) Corrubia, my sophomore quarterback, continues to display the blocking game he showed against Clifton, the Boilermakers will be in for plenty of trouble,” Pickett said.14

“Garfield met its toughest club Saturday,” Argauer claimed. “I don’t think any club will give us as much trouble as Irvington did.”15

Pickett, as usual before the Garfield game, worked his team behind locked doors at the stadium. Argauer, too, was taking no chances this time. He had sensed that Passaic regularly spied on his workouts at wide-open Belmont Oval, so he took the unprecedented step of closing practice. He had little choice after seeing the throngs hoping to watch the Boilermakers’ first workout of the week. When the team walked over from the No. 8 School locker room, they found the hill overlooking the field mobbed with spectators—in mid-afternoon. There were more there than at some high school games today.

Argauer wasn’t about to open up his playbook to the nosey onlookers, so he had the entire area cleared. As the fans grumbled, he posted guards at the every entrance to ensure they couldn’t return. It was futile. For the rest of the week, Argauer took the team to a field in neighboring East Paterson where he could prepare in peace.

Those drills didn’t exactly go well. The first string had a difficult time working against Passaic’s plays and, on Thursday, fullback Ray Butts, who had done a great job of blocking in the first two games, twisted his ankle. It was swollen so badly, Argauer doubted he could play. The inexperienced Al Kazaren took his place in practice. In addition, guard Jack Boyle had been smashed in the nose against Irvington and was having trouble breathing. Sophomore Ted Kurgan lined up there in practice.

Garfield’s first stringers line up at their Belmont Oval practice field shortly before the game against Passaic. Note the scraggly field and makeshift goalpost. The line, from left to right: Bill Wagnecz, Angelo Miranda, John Grembowitz, Pete Yura, Jack Boyle (with a bandaged nose), Joe Tripoli and Walter Young. The backfield: Wally Tabaka, Benny Babula, Ray Butts and John Orlovsky.

Courtesy Garfield Historical Society.

As the injuries kept the new whirlpool bath in the Garfield locker room whirring (the admiring press marveled at Argauer’s modern “hot water machine”), the papers trumpeted Passaic’s upset chances. The Herald News even noted that Garfield was coming off an unlucky thirteenth straight win. The paper didn’t explain why it wouldn’t have been even unluckier when the thirteenth win actually occurred. In any case, Passaic had more than a puncher’s chance.

East Rutherford stopped Babula last year and there’s no reason why Passaic can’t turn the trick. The Indians have an experienced line composed of six veterans and a letterman.Orlovsky and Tabaka are good ball carriers, always dangerous, but without Babula, the morale of the team is practically shot. Irvington showed that Garfield’s defense can be penetrated and if Passaic gives its ball carriers any kind of blocking, speedy (Mungo) Ladyczka and (Joe) Zabawa may get off to a long run. Garfield experienced trouble beating Passaic last year when the Indians presented a green line in their opening game.16

Elaborated the Bergen Record:

Realizing that Pickett has pointed his Passaic Indians for the contest, Coach Art Argauer appears a trifle worried. Then again, Argauer hasn’t quite recovered from Saturday’s thrilling contest with Irvington. Passaic gets its opportunity this week and the Indians have many followers who think Pickett’s club has the tools necessary to manufacture a victory.17

Both cities were on edge. Fans snapped up advance tickets at Geldzeiler’s and Sidor’s in Garfield and Markey Brothers and Rutblatt’s, the two sporting goods stores in Passaic. Garfield boosters were laying odds of 7-to-5 and in some cases 2-to-1. They were getting plenty of takers, although both McMahon and Del Greco cautiously picked Garfield to prevail by 7-0 and 13-7 scores, respectively.

Then, on Friday night, the fever pitch broke the thermometer. Some Garfield fans thought it a good idea to drive across the bridges into enemy territory and honk their horns while parading through the streets. Passaic fans were tipped off and were waiting for them with tomatoes, rotten fruit and vegetables, and, in some cases, rocks.

At Broadway and Gregory Avenue, Passaic boosters came out from between parked cars to let loose a storm of garbage down on one of the Garfield vehicles. In a pique of road rage, the incensed driver climbed out of his car and put up his dukes. Badly outnumbered, he was saved when local residents called police to the scene. His car, however, was thoroughly trashed.

Mistaken for a Boilermaker invader, an innocent bystander named Edward Baultz was driving home when he was ensnared in the melee. Brawlers stoned his car and smashed his windshield. Another Garfield contingent ran into a fusillade of refuse when it reached the intersection of Monroe and Market Streets. “It was a pleasure,” a Passaic rooter told The Herald-News. “Them Garfields got it all right.”

Passaic police protected the high school from vandalism, but some Garfield cars made it through to the Main Avenue business section where they created a ruckus and held up traffic.18

Dawn ushered in a nervous calm. The anticipation before the 2:30 p.m. kickoff seemed interminable, as the concrete grandstand filled up hours early. Up to 12,000 squeezed and elbowed their way through the gates. Stadium personnel were already ringing a flimsy wooden fence around the field as the teams—Passaic in red helmets, red jerseys and khaki pants, Garfield in gold helmets and jerseys, khaki pants and purple trim—trotted onto the grass to loosen up. Even the New York Giants hadn’t drawn as many to Passaic Stadium when they played Argauer’s Clifton Wessingtons. There was a palpable buzz in the air and, once the game started, spectators in the grandstand had to stand to get a view. It was as if it were the homily part of a high mass, except everyone fixed their gaze on the celebrants.

Argauer deferred his decision on his injured players until the warmup. Boyle had been fitted with a facemask to shield his nose—Young had been wearing one all year—and he’d start in his regular position. Butts was able to move around on his ankle but Argauer didn’t want to use him the entire game. Kazaren got his first varsity start. The game wouldn’t be too big for him. He was the starting third baseman on Garfield’s baseball team. He had confidence in his athletic abilities.

The teams eyed each other from their halves of the field. The Boilermakers knew their opponents well, knew they had All-State candidates in left guard Al Fadil and right tackle Joe Gawalis, part of what Passaic rooters were calling their Maginot Line, and a capable pass catcher in left end Dan Kuzma. The backfield featured Zabawa and Ladyczka, two kids from Passaic’s heavily-Polish First Ward, just across the Passaic and Monroe Street Bridges. Some players cursed each other in their parents’ native tongues. Sure, they shared deep-rooted cultural backgrounds, but the only thing they shared today was a shared ambition to topple one another.

That played out on the line where Walter Young played opposite Joe Gawalis, Passaic’s captain. Gawalis was plenty tough. He reached the Golden Gloves boxing finals that year, would play football at Georgetown and was a future Marine.

“On offense, every time he came to the line, he’d whack me on the head. Boom. Boom,” Young explained, still a bit peeved by the memory. “And I thought to myself, ‘this has got to stop. This has got to stop.’ There were no facemasks back then. So next time he came up to the line, my elbow found him right in the nose.”

Stunned, Gawalis confronted Young.

“You keep hitting me on the head, there’s more of this,” Young warned him.

“And that ended it,” Young said. “He didn’t hit my head anymore.”

With tensions that high, it would be as good a high school football game as one could ever see, not from offensive fireworks distinguishing great games today but, rather, from the import freighted in every snap, every contested yard. There was beauty in it, too—in the artistry of Passaic’s spinners, in Ladyczka’s punting form, in the precision of Garfield’s blocking and, especially, in the graceful power of Babula. Even the game’s violence seemed orchestrated with symphonic drama, the hits reverberating like bass drums.

There was no better example than the Babula run that helped set up the first touchdown of the game. The teams had thrown themselves up against each other for a full quarter when Garfield took over at the Passaic 46, and Babula called for the Boilermakers’ patented off-tackle smash right.

With his long legs, Pete Yura took his wide stance at center and, as soon as he snapped the ball, it seemed everything was set in motion with military precision. Babula was already moving to his right and lowering his shoulders when he caught the snap chest-high, five yards deep in the backfield. John Orlovksy, the wingback, slanted toward center on the right side of the formation, did a quarter-turn and fired himself through the hole. John Grembowitz, the right guard, exploded backwards out of his stance and pulled to the right to form Babula’s cordon with Wally Tabaka. Kazaren, the halfback, made a 90-degree turn out of his stance and, with Tabaka passing just behind him, laid his shoulder into the chest of Kuzma, who had penetrated upfield from his left end position.

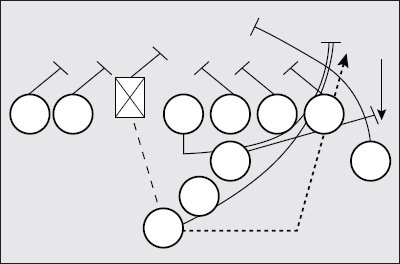

A diagram of Garfield’s devastating off tackle smash. Note all the moving parts and how they formed a wall of interference for Benny Babula.

The seal block prevented Kuzma from getting to Babula, but failed to knock him off his feet, and he pursued the play. Passaic players scattered across the ground as Babula turned the corner and tore through the hole with his great forward lean, his big strides eating up turf. Kuzma, trailing, raised his arms and considered making a dive at Babula’s heels from behind, but then thought better of it. Babula, with superb field awareness, now saw he could cut back to his left. He did just that, and stiff-armed Oliver Henry to the ground while Nick Corrubia, the Passaic safety, shook himself free of Young’s downfield block. Corrubia got a hold of Babula’s legs next, but another patented Babula stiff arm dispatched him. Babula almost lost his balance from the hit but, just before his knee touched, he braced himself with his right hand against the ground, righting himself, and kept going. Finally, Kuzma, on a great hustle play from behind the line of scrimmage, wrangled the big man down by his neck at the Passaic 26.

The play was an amazing in several ways. It hinged on superb, choreographed blocking as well as Babula’s vision, natural decision-making and, of course his power. And, it wouldn’t have been stopped without Kuzma’s determination. Preserved on film, one can watch it over and over in amazement to see all the pieces falling together.

If the Indians didn’t know it, they did now. Babula was a horse, and that horse was determined to carry the Boilermakers the entire day. Again and again, he called his number but, even though the Indians knew he was coming, they needed three, four and sometimes five men to haul him down. As the drive continued, Babula hammered on, absorbing blows, pushing forward. He gained another 15 to the six and, on three straight off tackle smashes, the horse plowed into the end zone. Orlovsky, the kicking hero of the Irvington game, missed the extra point. 6-0 Garfield.

The lead didn’t last long. Ladyczka sparked the comeback. First, he pinned the Boilermakers inside their 10 with a nice punt and, in three plays, the Passaic defense forced Garfield to punt. Babula barely got the kick off with Teddy Ryback charging him. It would have been a penalty for running into the kicker today, but no such rule existed. Ladyczka fielded the football at the Garfield 40 with running room. Sensing Bill Wagnecz coming hard to his left, he pushed off with his right foot, cut inside Wagnecz and escaped his long, futile reach. Grembowitz dove at him, but missed, and Ladyczka spun out of Orlovsky’s tackle. He was finally tripped up along the left sideline at the 20 amid a cloud of red clay dust kicked up from the baseball infield.

Here, Passaic went at the middle of the Garfield defense with Zabawa carrying the ball. The Indians kept blasting away inside the five until, on fourth down, Zabawa got behind right guard Murray Friend and tunneled in under four Garfield defenders. The score remained tied at 6-6 when Fadil’s kick was wide to left of the red-striped uprights, as a group of Garfield girls in bobby socks gleefully jumped up and down behind the end zone.

Both teams threatened to no avail in the remainder of the first half. Babula got loose for a couple of good gainers but Garfield lost the ball on downs at Passaic’s 31 when Orlovsky came up short on a pass from Babula. Louis Bednarz, at first unable to bring down Orlovsky by the neck, pursued him a second time, finally yanking him down, with his fist clutching the back of his jersey. The Indians took over and Ladyczka hit Bednarz with a 40-yard pass play, with Grembowitz saving a touchdown by running Bednarz down at the Boilermaker 20. On the next play, Ladyczka took a handoff from Zabawa on a spinner play and got around the right side. Grembowitz, from his knees, and substitute Ted Kurgan, from behind, combined to jar the ball loose and Tabaka recovered.

The half was nearly expired when Ryback got the ball back for Passaic by recovering a Babula fumble. But Garfield stuffed Zabawa on a spinner play up the middle and with Ladyczka running an end sweep, Young forced him back into Grembowitz’ grasp. The half ended with the Indians five yards short of what they used to call pay dirt.

Butts, who had entered the game for Kazaren in the second quarter, lost a fumble on Passaic’s 30 after Orlovsky and Babula had done some hard running on Garfield’s first possession of the third quarter. But the Boilermakers started their winning drive from their 32 on their next possession following a Ladyczka punt. It came with Argauer having scattered substitutes into his line as Kurgan, Julius Fick. Ed Leskanic and Len Macaluso all played parts.

Babula quickly hit Tabaka with a pass for a first down and, with Grembowitz and Butts laying down defenders ahead of him, gained 16 yards round his end before running into the Passaic cheerleading squad. Switching up his calls, Babula turned into lead blocker for Orlovsky on two straight runs and continued to cross up the Passaic defense with a pass to Butts who lateraled to Tabaka for 12 yards to Passaic’s 17. That was enough fooling around. They instead resorted to blunt force and that meant turning the horse loose. Babula dragged four Passaic defenders for 12 yards to the five, then, on the second play of the fourth quarter, he ran an off-tackle smash to his left and followed the blocks of Orlovsky and Macaluso into the end zone. Orlovsky missed the extra point but Passaic was offside, so Babula gave it a try—but missed.

Babula inadvertently gave Passaic another chance when he tried to run with a fake punt and was stopped short of the first down at the Passaic 40. The Indians moved to the Garfield 25 on the strength of Ladyczka’s arm, but he threw one pass too many when Tabaka intercepted and returned it 19 yards to the 29. Garfield could have added to its winning total but Orlovsky fumbled as he crossed the goal line. Butts ended the game with another interception of Ladyczka.

When they added up the stats, Babula had run for 193 yards, more than tripling Passaic’s total. Garfield totaled 259 rushing yards to Passaic’s 59, more than negating Passaic’s 119-44 edge in passing yardage. Garfield finished with 15 first downs to Passaic’s eight. As well as Passaic fought, it was, in the end, Babula’s day and another example of him coming up big in the big games. McMahon and Del Greco agreed.

“He’s the Difference,” Del Greco wrote in capital letters. “Irvington looked classier than Garfield. Benny brought the Camptown team to its knees. It was Benny who beat Passaic on Saturday. Garfield High’s men simply blocked and Babula ran wild. He packs tremendous power. And yet, the opponents know he’s raking the ball. They’re laying for him but he just can’t be had.”19

“The difference between Passaic and Garfield on Saturday was Benny Babula,” McMahon wrote, as well. “It is the same difference that lifts Garfield from the ordinary football class to the first flight in New Jersey schoolboy championship ranks.”20

The game was a win-win for Garfield, a win on the field and a win at the gate. As the home team, Garfield took in $4,237 in ticket receipts and put out about $230 in incidentals, including $70 for the rental of the stadium, to turn a profit of over $4,000. That windfall made its dispute with East Rutherford, the next opponent, rather ironic.

East Rutherford: Daylight Saving

The original schedule had the teams meeting under the lights at Passaic Stadium Friday night as they did the previous year. That game drew a big crowd and, as the host team, Garfield took in $2,200 and offered East Rutherford just a $15 guarantee, which the Board of Education upped to $75 after East Rutherford athletic director and coach Jimmy Mahon made a personal plea. Now, it would be East Rutherford’s turn to make a box office killing.

But a week before the game, Mahon suddenly received a letter from the Garfield board announcing that night games were henceforth banned and that the game would have to be played on Saturday afternoon. “After giving due consideration to all circumstances and the danger to the health of the players, the above decision was unanimously decided upon,” it said.21

Mahon and the East Rutherford officials were incredulous, but there was nothing they could do beyond airing their side of the story, which Mahon did by calling McMahon and Del Greco.

“When Art Argauer asked me last year to play our game at night, I told him it was all right with me if I could get the permission of my superiors,” Mahon explained. “I got the permission and then asked Art if he would agree to play a night game in 1939 so that we might have a chance for a good gate. He agreed and we played.”

Mahon said he double-checked with Argauer several weeks before the season began and was assured that the rematch would be played at night.

“Now, though, I get a letter from the Athletic Council informing me that night games for Garfield are banned because they are injurious to the players,” Mahon went on. “Argauer says Garfield couldn’t see my kids last year. As a matter of fact, it was just the opposite. Sekanics scored a touchdown (on the opening kickoff) before we could get accustomed to the lights. As it later turned out, that touchdown meant the ball game.”22

Mahon had a point about what Al Del Greco called Garfield’s “trumped-up squawk,” although the lights were really quite poor. Garfield barely escaped with a 13-7 victory as East Rutherford controlled the play. A loss would have cost the Boilermakers the state championship. Argauer vowed immediately after the game that he’d never play another night game— Christmas games in Miami eventually excluded, of course. Obviously, this time, he wanted to avoid adding another variable that could affect the outcome.

East Rutherford was a tough enough opponent that always pointed to Garfield as one of the biggest games on its schedule. Paterson Central had trampled the Wildcats in their last game two weeks earlier, after East Rutherford tied rival Rutherford in their season opener, but their record hardly mattered. They historically played the Boilermakers tough.

East Rutherford was the only opponent Garfield had faced every year since the program began in 1922 and Argauer was 5-2-1 against Mahon since he took over in 1930. The 1932 contest, a 6-6 tie, erupted in fisticuffs in the fourth quarter when every man on the field squared off with an opponent as if it were a hockey game. Spectators soon rushed onto the field to join the melee, which carried on for five minutes until Passaic police broke it up. Each school considered cutting off relations with the other, but didn’t. Yet, certainly some bad blood remained and now, a little more was split with Garfield’s refusal to play at night.

Mahon was riled up. He prepped his team as if it were the biggest game left on the schedule. Which it was. He knew this was a perfect spot to spring an upset. The Boilermakers were coming off two intense, physical games against Irvington and Passaic. They were a little banged up, while East Rutherford, having not played the previous week, was in top shape. Plus, with Irvington and Passaic behind them, everyone was talking about how Garfield had just one big hurdle left—unbeaten Bloomfield, two games down the road.

“Everybody but Art Argauer expects his championship club to draw a breather at East Rutherford,” the Bergen Record noted.23 Del Greco, the Garfield alum, and McMahon, the East Rutherford graduate, made their predictions accordingly.

Del Greco:

The club which knocks off Garfield will be some sucker outfit, not conceded a chance. East Rutherford isn’t a sucker outfit by any means but it has a whale of a chance for that Jimmy Mahon can always steam up a club which plays against Garfield. However, Benny Babula is still with the champs and I look for Garfield to win by a 20 to 7 score.24

McMahon:

Over in Garfield this is considered a breather for the hard charging Boilermakers. And indeed, the Wildcat record for the year makes it look like one. On the chance that East Rutherford will never roll over and play dead for an old rival like Garfield, I’ll call it respectably close. Say 19-6.25

Mahon was telling people to expect an upset as the game, played at Riggin Field in East Rutherford, neared. As with everyone else, he felt the key to beating Garfield was up-front and, with the extra week of prep time, he worked in a new wrinkle by shifting his line to Garfield’s strong side, where Babula did his most of his running. Then, Argauer decided to start backup Bill Librera in Babula’s place along with a few other regular backups. It made no sense. After telling his team not to take the Wildcats lightly, he was doing just that.

Librera was a capable backup who would star as Babula’s successor in 1940, but this wasn’t his day. He fumbled when the Boilermakers reached midfield immediately after the opening kickoff and, after the Boilermakers stopped three East Rutherford rushes, he fumbled receiving the punt. The Wildcats quickly turned that into a 6-0 lead when Joe Sondey hit Ed Subda with a two-yard scoring pass after the Boilermakers fell for a fake handoff.

Argauer left his second teamers in for one more offensive series that went nowhere and East Rutherford was forced to punt one more time. Now Argauer sent Walter Young in off the bench, and the gangly end came around the corner to block Subda’s kick and recover on East Rutherford’s 19. Now Babula went into the game and picked up 17 yards to the two, followed by a two-yard TD run by Tabaka. Argauer chose to run for the PAT and Babula plunged over to make it 7-6.

For the second straight week the first half whistle saved the Boilermakers. The home team was at the Garfield 13 when the half ended. Although the Boilermakers controlled the second half, limiting East Rutherford to only three possessions, they scored only once, on a 15-yard pass from Tabaka to Young, who played hero for the second time, then kicked the extra point to boot. It also came on the play after Babula left the game with an injured leg. Mahon’s game plan didn’t stop Babula completely, but it did tie him up. The Wildcat captain, Ed Bode, had two hard tackles that sent Babula to the sidelines.

Garfield had a chance to add to its lead late but was stopped inside the one-yard line. No one on its sideline was happy with the 14-6 win. Argauer was probably happy the game hadn’t been played the night before, if this was how things went during the day.

“I’m afraid the boys can’t stand prosperity,” he said. “Unless they awaken to the fact that they can be beaten, they will be on the outside looking in when the title is handed out this year. Of course I’m partly to blame for starting the second team against East Rutherford.”

The record stood at 4-0 and the critics began to howl. It was one thing to escape with narrow wins against state powers like Irvington and Passaic. But East Rutherford? Wrote McMahon:

Benny Babula is apparently All State everywhere but East Rutherford. The Wildcats stopped him cold and just to show that it was no fluke, handcuffed him again Saturday. East Rutherford’s football camp treats the entire Garfield title unit with the same disrespect, as a matter of fact.

The narrowness of Garfield’s last three victories makes that November 4 tussle with Bloomfield loom very important in Art Argauer’s program. The Bengals are coming on fast. They had to have something to whip Central, 19-0. That same Central team walloped East Rutherford, 34-6, just to give you a hint of its merit.

Still, unlike some, McMahon wasn’t predicting doom:

Disregarding all the storm signals, I’m going to stick with Garfield to win the state title. The Boilermakers have what it takes when they are under pressure.26

Thomas Jefferson: The Breather

Before the Boilermakers got to their next pressure spot against Bloomfield, they took on Thomas Jefferson of Elizabeth, the team that briefly challenged them for state laurels the year before. The Jeffs, however, were decimated by graduation and their 1939 team was a disaster. Not expecting much competition, Argauer scheduled two scrimmages during the week, the first against Ridgefield Park, the second against Rutherford. Babula, still limping from the injury sustained against East Rutherford, was held out of both. Orlovsky threw out his shoulder making a block against Ridgefield Park and it was feared he was lost for the season. Meanwhile, Otto Durheimer, one of Babula’s backups, developed pain in his side and was rushed to the hospital to have his appendix removed. It was a good thing that Elizabeth didn’t offer much competition.

The game, played at Williams Field in Elizabeth, was a 26-0 rout. To replace Orlovsky, Grembowitz was moved from the line into the backfield and young Steve Noviczky got his first start at right guard. Alex Yoda, who showed power in the Passaic game, started at left guard instead of Tripoli. Babula, playing on his sore leg, ran for two TDs plus a conversion and passed to Tabaka for another score. Argauer was able to sit down his regulars in the fourth quarter and Red Barrale, who was turning 20 the day of the Bloomfield game and becoming ineligible, was given the chance to direct the team in his final game. He scored the last touchdown on a one-yard run then took off his shoulder pads seemingly for the last time.

The win allowed Argauer just a momentary pause to catch his breath before the epic clash with Bloomfield. With their fifth straight win and sixteenth overall, the Boilermakers moved past the midway point of the season. They were ranked number one in the state in both the Colliton System and by the Jersey Journal. With the first rankings now released, the competition for the state title was getting clearer.

Close behind Garfield in the Colliton ratings was undefeated and unscored upon East Orange, followed by Nutley, also undefeated and unscored upon, then Columbia and Bloomfield, both unbeaten. Vineland, the defending South Jersey champ that so wanted a post-season showdown with Garfield in ’38, was also unbeaten and unscored upon but the Poultry Clan’s schedule was working against them again, and they trailed the five North Jersey schools in points.

Vineland fared better in the Journal’s ratings, which had it in a three-way first-place tie with Garfield and Nutley with Woodrow Wilson of Camden, yet another unbeaten team, close behind. That began to give Clan supporters hope for at least a title shot with a post-season clash.

The mish-mash would be settled somewhat in the coming week. Of the 10 unbeaten teams among state contenders, six were in action against each other. The Garfield-Bloomfield tussle topped the Saturday slate with Vineland at Atlantic City the top attraction in the southern part of the state. On Tuesday, Election Day, Nutley was visiting East Orange at Ashland Stadium. Paul Horowitz speculated that the winners could be 1-2-3 in the next Colliton ratings.

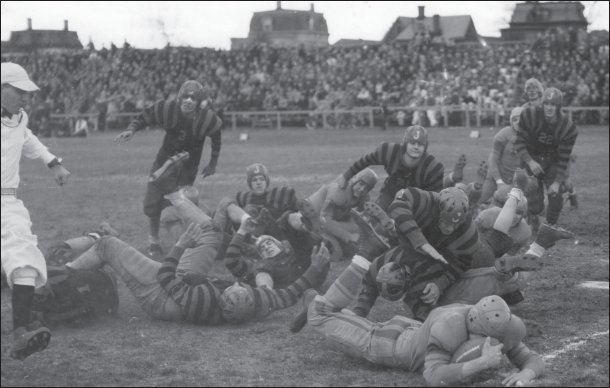

Benny Babula dives across the goal line, leaving a sprawled jumble of Thomas Jefferson defenders in his wake. Courtesy Estate of Angelo Miranda.

Bloomfield: Green Pastures

Argauer and his players weren’t paying much attention to Nutley or anyone else. Beating Bloomfield seemed a perfect path to repeating as state champs with Asbury Park, Paterson Eastside and Clifton closing out the schedule. And the Bengals were converting plenty of believers.

After Bloomfield’s impressive win over Paterson Central, Frank Fagan of the Newark Star Eagle warned Garfield that Foley was “waving his magic wand” again.27 Foley wasn’t expecting much from his team before the season, especially after the Bengals were bounced around by powerful East Orange in a scrimmage. He noted his team was “younger and lighter” than any he’d coached in eight years—but he did feel it had a chance to play spoiler against the three opponents with title aspirations—Garfield, Nutley and Irvington.

By Garfield week, the Bengals had exceeded Foley’s expectations. While their schedule was less stellar than Garfield’s—with only Paterson Central regarded highly—Foley’s reputation convinced many neutral observers that he had the makings of another state title team. Garfield, meanwhile, had its doubters, all pointing out the nail-biters the Boilermakers played against Irvington, Passaic and, especially, East Rutherford. Relying on what he heard from “scouts,” Herb Kamm, the sports columnist for the Asbury Park Press, was the leading voice of critics calling Garfield overrated.

“The Boilermakers are a good club and they’ve piled up a nice stack of points already under the Colliton system,” Kamm penned. “But the report is that Art Argauer’s 1939 edition isn’t as strong as some of the enthusiastic scribes up that way would have you believe—which may be good news to Asbury Park’s gridders, who’ll have the pleasure of finding out for themselves in another week come Saturday.”

Kamm noted that Thomas Jefferson coach Frank Kirkleski, after his team’s 26-0 loss to Garfield the week before, described the Boilermakers as the easiest team his boys had played in five weeks. It was an odd pronouncement, considering Argauer had emptied his bench in the second half and had used 32 players against the Jeffs. But there it was.

“Argauer pits his charges against Bloomfield this Saturday and the word up that way is that the Bengals are loaded for bear, eager to avenge a 19-0 setback they suffered in the clash between the bitter rivals last year. Bloomfield stands a good chance of ending Garfield’s victory streak,” Kamm surmised.28

Argauer had other concerns. There was the matter of Orlovsky’s shoulder. He’d been seeing a New York orthopedic specialist who was somewhat optimistic that Orlovsky could play with a brace, but he hadn’t given his final approval and Orlovsky hadn’t practiced all week. And even if he had been wholly recovered, there was a chance that Librera and end Ed Hintenberger would be unavailable. Both were scheduled to report to Fort Dix the morning of the game for a week-long National Guard camp. Argauer was frantically trying to pull strings, calling “everybody but the President,” noted Art McMahon. The coach couldn’t figure out how Hintenberger and Librera got themselves committed anyway since each was under the 18-year age limit. “It would be funny if the threat of war kept Garfield from winning a football game,” McMahon wrote.29

With Orlovksy’s status in doubt, Argauer was trying to find a way Red Barrale could play. Barrale was turning 20 on game day, about two-and-a-half hours after kickoff, to be precise. He planned to ask for Foley’s permission. Such agreements had been made in previous seasons. In the end, he thought better of it, knowing that other teams might protest Barrale’s eligibility, and he didn’t want to risk a prospect of forfeit.

It was also raining during the week, which curtailed practice sessions. Both Foley and Argauer claimed the weather as a disadvantage to his team. Argauer complained it was difficult to adjust his lineup for injuries and to install the five new plays he planned to unveil against Bloomfield.

Of course, even without Orlovsky and Barrale, Garfield would still have Babula, but he, too, was preoccupied. He came to practice each day worried about his mother, who was seriously ill. The Newark Sunday Call had put together a photo spread of Babula at home with his family, at school with his girlfriend Violet Frankovic and surrounded by adoring Garfield kids. It was to run in the paper’s magazine section the day after the game. But that happy tableau was being overshadowed. When Babula left his house the morning of the game, doctors were considering whether Tillie Babula needed surgery. They decided to forgo the operation to ease Babula’s mind. Still, he’d go into the biggest game of his young life knowing there was much more at stake than a football game—even if it was the football game of the season in New Jersey. As The Herald-News put it:

As far as Garfield and Bloomfield supporters are concerned, the Nutleys, East Oranges, Columbias and the rest of the undefeated Group Four football teams might just as well take a back seat and forget about the state championship. Tomorrow, the Boilermakers and Bengals collide at Foley Field, Bloomfield in the outstanding schoolboy struggle in the state this week, publicized as the state title clash.30

A view of the overflow crowd of 19,000 that jammed Foley Field to witness Garfeld’s 18-0 win over Bloomfield. Newark Sunday Call.

Game day morning brought freezing temperatures to North Jersey as fans gulped down coffee and hot chocolate to brace for the contest. By 11:00 a.m., parked cars jammed the streets around Foley Field, and it was soon apparent that the crowd could exceed record proportions. When the Newark News reported that extra bleachers had been brought in, the paper said they were “ample enough to supply the crowd,” but that was hardly the case.

Officials posted an “S.R.O” sign an hour before kickoff and, 30 minutes later, Bloomfield police closed the gates to all except advance ticket holders. They entered the stadium, passing the shutout, begrudging latecomers. More than a thousand of them, however, managed to secure vantage points from the hill outside the stadium. The entire scene pulsed with humanity and 50 Bloomfield cops circled the field to keep order. Among the throng in the wooden grandstands on Garfield’s side of the field were Walter Young’s father and mother, at the only football game they would ever attend. They could not believe the fuss their son and his playmates had kicked up. The crowd was estimated at 19,000, not including those outside the stadium. More eyes watched this high school game than any other before in New Jersey.

As usual, there was a lot of betting action between the grandstands. Del Greco had predicted a score of 13-6, Garfield, McMahon, 18-7, Garfield. During the week, bookies were laying odds of 8-to-5 for Garfield backers, 6-to-5 for those taking Bloomfield. With the cockiness afforded by pregame Adrenaline, and the courage provided by hip flasks, each side was settling for even money now.

Bloomfield fans started a taunt: “California, Oregon, Arizona, Texas. We play Garfield just for practice.” Meanwhile, Red Simko didn’t disappoint. He walked up and down in front of the Garfield stands, tossing lollipops to cheers. As he did, a helmetless Babula warmed up with punts soaring over 70 yards. The Bengals always looked intimidating. Their snappy black jerseys with red trim made them appear larger than they were—and they were large. But all eyes were on the 6-1, 190-pound Babula, who was, as always, larger than life, now appearing even more classically heroic with his curly blonde locks.

A Steve Bognar cartoon in The Herald-News during the week had asked, “Can the Bengals stop the Garfield terror?” and “If so … can they upset the Boilermakers?” Bognar also asked if Red Simko would be there to cheer on his team? The answer to the last question was yes. The answer to the first question would be no, making the second question irrelevant.

Argauer didn’t have to pull strings with the National Guard. As it turned out, they were due to report Sunday, not Saturday. Even so, Orlovsky would not play. His New York doctor had fitted him for a brace. But the shoulder still needed healing and he’d have to rest two more weeks.

At last it was 2:30—game time. Bloomfield’s opening kickoff, to a crescendo of cheers, bounced to Wally Tabaka, ace return man, who raced with it 18 yards before he, as he almost never did, fumbled the ball. A huge roar erupted from the Bloomfield side as kicker Bill Greenip threw himself on it at the Garfield 35. Two running plays netted a first down at Garfield’s 25 and two more set up third and seven at the 22. Here, the Bengals tried to bait the Boilermakers with a misdirection play. The interference went left while Bob Kerr tried to sneak around the right side. But Young had learned his lesson from the 1937 Bloomfield game, when he had put himself out of position and got an earful about it from his coach. This time, he stayed put and threw Kerr to the ground for a five-yard loss. The Bengals then tried a fourth down pass but turned the ball over on downs.

The Boilermakers couldn’t move, so Babula punted down the right sideline. Kerr neatly caught the ball on the dead run and was heading for daylight. Wagnecz, whose job, like a modern gunner, was to get up the right side as swiftly as possible, was caught flat-footed. But, out of desperation, he lunged for Kerr’s arm and the ball popped loose. Jack Boyle beat Kerr to the bouncing ball for the recovery. It was a mistake on Kerr’s part. He should have been carrying the ball in his outside arm.

For Garfield, it was a second bullet dodged. The third came after a fourth down try from the Boilermaker 48 when Yura’s errant snap from center went over Babula’s head. But two plays later, Bloomfield returned the gift. Ray Butts, who played a tremendous defensive game behind the line, recovered Francis Vesterman’s fumble. The Bengals’ offense would not see Garfield’s side of the field again although Vesterman would curse his hands one more time when he was unable to hold on to what would have been an interception, juggling the ball and finally dropping it five yards later with an open field in front of him.

For Garfield, the uncharacteristic sloppiness of the first quarter luckily went unpunished. When the teams switched sides, Tabaka got it started with a 15-yard punt return to the Garfield 46. Babula took Yura’s snap and followed his blockers around left end, where he slipped two tacklers and stiff-armed a third for 18 yards, his longest carry of the game. Now, Babula drifted to his right and, with his sidearm delivery, whipped a pass to Young, who lateraled to Tabaka for a gain to Bloomfield’s 32. Babula got 10 more yards on an off-tackle smash and hit Tabaka with a pass inside the 10.

Little Roy Gerritsen struts his stuff at halftime of the Garfield-Bloomfield game at Foley Field as drum majorette Margaret Hoving leads the way. The Herald-News.

The Bengals’ defense was winded, leaning over at the waist. Still, they ganged up on Babula to stop him for no gain. They would not do it twice. On the next play, the big guy went off left tackle, gave one defender a straight-arm and outran another into the end zone. He was inches short on a plunge for the extra point. The halftime whistle blew with Garfield leading, 6-0. Each team went into the lockers knowing it had a chance, but Bloomfield also knew it has squandered opportunity against a good team. Garfield could feel it was taking over the game as long as it could hold onto the ball.

Outside the locker rooms, there was quite a stir. Five-year-old Roy Gerritsen, decked out in a purple band jacket, white hat atop his head, was making his debut as the Garfield High band’s tiny drum major. He marched down the middle of the field with his cut-off baton until he reached the 50-yard stripe.

There, he gave the signal for the band to come onto the field. Led by drum majorette Margaret Hoving in her smart outfit and cape, they joined him and played on. The 5-foot-7 Miss Hoving and 3-foot Roy made quite the sight as they twirled away to the music. Gerritsen’s parents were a bit apprehensive as their son was about to take the field before 19,000. But he eased their fears. “Mom and Dad, you make me laugh. Why are you so nervous? I’m not,” he said.31

Neither were the Boilermakers when they emerged from the dressing room. They would score a touchdown in each of the last two periods while completely stifling the Bengals’ attack. Babula was inexorable. When Garfield marched 65 yards in the third quarter, Babula carried the ball seven consecutive times for the final 26 yards. Somewhat tired, Babula went to the air during a 60-yard fourth quarter drive, where he ate up 40 yards with two passes to Young. When the drive reached the four-yard line, Babula spread the glory. Tabaka had just let a touchdown pass slip through his fingers and, when his teammates urged Babula to score again, he instead called a play for Tabaka, who went in over left guard.

Babula injured his hip when blocked on the subsequent kickoff and stayed in the game for a few plays to shake it off. When he came off the field with 2:00 left, he received a thunderous ovation, as did Tabaka when he came out. Even the Bloomfield fans appreciated Babula’s dominating performance in the 18-0 win.

When they tallied the stats, Babula, on 26 carries, had gained 106 of Garfield’s 142 yards rushing and completed nine of 13 passes for 116 yards. Three of his four incompletions were drops and seven of his nine completions went for more than 10 yards, no small feat in those days. Babula also averaged 36 yards on six punts, including one that went for only 10 yards because Grembowitz backed into him. And, on one of Tabaka’s punt returns, he laid out three Bengals with one block.

Bloomfield was completely shut down. Young, Noviczky, Yoda, Boyle, Grembowitz and Butts were singled out for their play. The Bengals netted 20 yards rushing after netting minus-13 yards in the second half. They didn’t complete a pass in seven attempts. The only things Garfield didn’t conquer were the goalposts. Those 50 Bloomfield cops prevented Garfield fans from getting close, unlike 1934 when the two fan bases did battle over them.

In his game story for the Star-Ledger, Sid Dorfman wrote: “It was plainly a case of too much Bennie Babula. If there was something Babula failed to do, it went by unnoticed. He was in just about every offensive play Garfield tossed at the bewildered Bengals, running, passing and kicking the Foley brigade dizzy in as great an exhibition as this season will see. It was simply Babula against Bloomfield and the All-State back collected.”32

But was it that simple? To say that was to ignore the coaching dynamic on display between Art Argauer and Bill Foley, two masterful football strategists. In the end, the game stood out, undoubtedly, as one of Argauer’s masterpieces. Argauer not only motivated his team into its finest performance, but also devised a brilliant game plan while cleverly negotiating injuries and uncertainty. For the first seven years of their rivalry, Argauer was the challenger punching above his weight. But in ’38 and ’39, the roles were reversed. Argauer had the better team. While on top, Foley never played chess with X’s and O’s. He ran his T-formation, sometimes shifting into a conventional single wing; but you either stopped it or you didn’t. Then, before the 1938 game, Foley claimed he found a way to stop Babula. But couldn’t.

That’s not to minimize Foley’s coaching brilliance. His teams were so finely tuned and so filled with “confidence born of demonstrated ability” that opponents were routinely caught up in the gears of the machinery. Argauer always looked for the monkey wrench, whether in his early preparation in 1934 or, as the favorite these last two years, to exploit Bloomfield’s weaknesses.

Yes, Argauer had Babula and he was daring Bloomfield to knock him off. The papers wrote about the five new plays he would use, but he never did. As usual, everything worked off the off-tackle smash. But Argauer also tweaked the game plan to include more reliance on the passing game, which seemed to catch Bloomfield off-guard. Defensively, he stopped the Bengals cold by using four different alignments, a 6-3-2, a 5-4-2, a 5-3-2-1 and a 6-2-2-1. On passes, he dropped a lineman into coverage, a modern innovation.

He also went deep into the lineup and mixed things up, partly out of necessity due to Orlovsky’s injury, and he continued to do so throughout the season. The right side of the line was totally different than on opening day. Young Steve Noviczky was at right guard, where Grembowitz had been playing, Al Yoda had played himself into a starting job at right tackle and Ed Hintenberger had surpassed Bill Wagnecz at right end. Big Joe Tripoli was also moved back to the second unit with stocky Angelo Miranda changing sides from right to left tackle. Center Pete Yura and left end Walter Young were the only fixtures at their original positions.

Benny Babula’s mom, Tekla, serves him and sister Eva Polish specialties in one of the pictures that ran on the Newark Sunday Call’s magazine photo spread. Newark Sunday Call.

When Babula jogged off Foley Field, passing through the phalanx of backslapping Garfield fans, many of them a little richer from his exploits, his thoughts were only of his mom.

The team bus pulled up. Babula was away from the tumult now, but, as he climbed on, Lou Miller of the New York World-Telegram was waiting for him.

“Ben, got a minute?” Miller asked, extending his hand.

Babula could not have put on a better show for the New York press, which had crossed the river to check him out personally. But, as Miller noted in a story that ran Tuesday, “scant light heartedness was apparent on the classic Babula features as the big Polish boy boarded the bus for home. Although he had just given one of the finest triple-threat exhibitions of the year, Benny was worried about his mother, who was ill at home.”33

Babula, not exactly in the mood, was polite but no great interview. He did tell Miller that he might not be playing college football. Miller went on to write that Babula was haunted after every game by “his mother’s anxiety.” Tillie didn’t want to see her boy get hurt and he was thinking of quitting the game after high school to ease her mind. Miller claimed Argauer told him so. An exaggeration? That wasn’t beyond a newspaperman’s desire to sell papers in the 30s, and it made the story juicier with Benny now more worried about his mother than she had ever been about him. That wasn’t exaggerated.

Babula drove home from the high school as quickly as he could. It was euphoria around town as evening fell. He passed cars tooting horns, people out on Palisade Avenue walking almost above the sidewalk. Across the Ackerman Avenue Bridge he went and, when he entered the house on Trimble Avenue, his father greeted him with a huge smile and hearty handshake. All was good: his mother’s condition had improved, and there was no need for an operation.

Babula could finally take in all his good fortune in one giant exhale. With his mom on the mend, things could not have been better, and the future much more promising. Babula telephoned Violet then slept well that night. The next morning, his family opened the Newark Sunday Call to a full-page photo spread: “Day with Ben Babula, Garfield’s All State Quarterback.” The captions below the glossy pictures made him blush:

Sort of pensive is Bashful Ben on way to school in Garfield; his “queen in calico,” is Miss Violet Francovic (sic).

Even football stars must study. Here is “Golden Boy” in classroom, absorbed in something or other.

Then, for a hearty luncheon at home with his mother, Mrs. Michael Babula, and his sister, Eva.

Admiring youngsters listen to Babula’s explanation of how the game was won.

On gridiron Coach Arthur Argauer points out to his ace player some new wrinkle in practice of Ben’s teammates.

Ben’s on the loose—as hard to stop as a locomotive. Looks like another Garfield score.34

Babula didn’t like publicity, but there was no stopping the hero treatment now. It was the business of newspapers in those days. Heroes were needed and, sometimes, created. Babula came ready-wrapped. Even the New York City papers were touting Babula as the best high school player in New Jersey. And the Jersey papers agreed. Frank Fagan of the Star-Eagle for instance:

Garfield may have other challenges hurled in its direction but so long as Benny “Bingo” Babula is at large the Boilermakers have nothing to fear. It is the opinion in this corner that Garfield, with Babula going Bingo on those chalked lines whenever he desires, will come into its second New Jersey Group 4 championship.

Babula is above the average schoolboy football player. He can do most anything on the football field and, with the expert blocking given by his teammates; he probably could make a joke out of any scholastic eleven in the state.

Bloomfield today will tell you that Garfield, without Babula, is just another ball team (but) Argauer has a great team, even greater than the one which won the title last year.35

It certainly seemed that way now, with the hardest part of the schedule behind them. Joe Lovas of The Herald-News wrote of “green pastures ahead,” that “unless the Boilermakers suffer a severe letdown in their remaining games, they are assured of their second straight New Jersey Group Four championship.”

Art McMahon concurred:

Garfield has only itself to worry about from now until the close of the football season. Asbury Park, Paterson Eastside and Clifton would be deep dish apple pie and ice cream after Irvington, Passaic, East Rutherford and Bloomfield.36

But not everyone was thinking that way, certainly neither East Orange nor Nutley, scheduled to meet on Tuesday in the wake of all the breathless Garfield title chatter. No one could yet say with certainty that Garfield would come out on top of the Colliton rankings if it won its last three games, so both Nutley and East Orange held legitimate state title visions.

Those two Essex County communities were totally different in character. By the turn of the 20th century, East Orange had evolved into a wealthy suburb of Newark, its eastern neighbor. In the 30s, it retained those characteristics of big homes and leafy avenues with a central business district that included glitzy department stores such as B. Altman and the 10-story Hotel Suburban with a well-heeled clientele. Meanwhile, throughout its five neighborhoods, the city’s demographics were a diverse mixture that included Jewish, Irish, Italian and other European ethnicities along with a growing black population that was reflected in the football roster. The city and school had made some racial progress since the swimming pool incident of 1933.

Nutley, on the far end of Essex County adjacent to Clifton, also held an equally interesting, albeit different, past. Its brownstone quarry had been a magnet for Italian immigrants, particularly from the province of Avellino. The quarry was abandoned in the late 20s, and a famed bicycle velodrome with seating for 12,000 was built there. When cycling’s popularity faded, its boards were converted for midget auto racing, ignoring the safety dangers of so steeply pitched a track. They called it the “Death Bowl.” Upon the third fatality of the 1939 racing season, it was closed in August.

By 1939, Italian-Americans who had originally worked in the quarry became firmly entrenched in Nutley. They had worked through earlier prejudices prohibiting them from even walking through some parts of the borough. Now, their sons comprised the vast majority of the high school’s football roster. No one, not even the bluest-blooded of Nutleyites, complained.

The contrast of the two towns existed, too, between the two teams’ coaches. At age 48, Nutley coach George “Chief” Stanford was one of the longest-tenured coaches in the state. He played on Newark Central’s first football team in 1912 and then professionally in California and Nevada. While serving in France near the end of World War I, he received a letter from Dr. F.W. Maroney, the state supervisor of physical education, about the coaching vacancy in Nutley. Although he hadn’t attended college, he got the job in 1919 after completing a physical education course. That began a fantastic 23-year coaching career that included four state championships in baseball and three in football. Stanford drilled his teams hard in fundamentals and produced quality teams year after year. His 1922 championship team was led by Frank Kirkleski, the Elizabeth coach.

East Orange coach George Shotwell was just 28. He had been an All American center at University of Pittsburgh, which dominated college football in the early part of the decade. Shotwell had a string-bean body at 159 pounds and at 6-feet, was diminutive for a center, even back then. But he was technically proficient and, in a day when every hike required a long snap, Shotwell had never flubbed a snap his entire career. He also has a very high football intelligence quotient, and was rightly known as a “keen diagnostician of plays” who was unsurpassed in that respect, according to his coach, the legendary Jock Sutherland

“I am perfectly willing to admit that Shotwell is the most remarkable center I have ever seen,” Sutherland said in 1934. “If all my centers in the future are more Shotwells, I’ll be satisfied.”37

Shotwell first coached at Hazleton High School in his native Pennsylvania, where he took over a losing team and lost just three games in two seasons. In 1938, East Orange, with no shortage of funds, coaxed Shotwell to New Jersey with a $4,000 offer, a $1,400 raise. East Orange, like Hazleton, was starving for victories when Shotwell arrived. Then he went 8-1-1 in his first season and undefeated his second. A feature article in the Star-Eagle ranked him the No. 1 citizen in the city.38

Shotwell brought with him Pitt’s offense, the “Sutherland Scythe,” a variation on the single wing that moved the wingback further off the line of scrimmage. But he used just 10 plays. That’s all East Orange needed.

Both coaches met tragic ends. Shotwell, down on his luck, was one of 30 victims in a 1981 fire at a boarding home in Keyport, N.J., that would lead to more stringent state regulations on such facilities. Stanford, the World War I veteran, re-enlisted as a captain in World War II. He died while at home on leave of a heart attack on April Fool’s Day, 1943, having taken his leave of absence from Nutley the previous May.

When Stanford met Shotwell in 1939, each had arguably his strongest team ever. While the papers had hyped Garfield-Bloomfield as the game of the year, these two powerhouses were actually more evenly matched. Gus Falzer gushed, “chances are there will be more fighting there than on the West front in the European War.”39

Nutley, led by Frank Cardinale, the state’s leading scorer with 96 points, had been destroying the opposition, 176-0, in total. Their fans were already drawing comparisons with Garfield. One curious fellow reported back to Nutley Sun sports editor Walt Maloney from the Garfield-East Rutherford game. Babula, he said, “couldn’t carry Frank Cardinale’s water bucket.”40

But after watching Babula romp over Bloomfield, Maloney wrote, “This corner must disagree with those who have been telling us that Garfield’s Benny Babula is not a great back. On the basis of his performance in the Bloomfield game, we’d say that Babula is Garfield and without him the Boilermakers would be just another team. Perhaps he’s not as spectacular or as fast as Nutley’s Frank Cardinale but he’s a 190-pound, six-foot back that any coach would like to have.”41