It was as if everyone from the city of Garfield had chipped in for an Irish Hospitals’ Sweepstakes ticket and collectively hit the jackpot. Against odds that seemed just as long … their Boilermakers were going to Miami.

Paperboys around town delivered the glad tidings that rainy morning. The Herald-News screamed, “GARFIELD TO PLAY MIAMI CHRISTMAS” across its front page, pushing the war news down below the fold.

The players wore their lettermen sweaters to school, the underclassmen in purple and the seniors in white. Even the teachers had a hard time concentrating on that day’s lessons. There were pats on the back for Michael Babula as he made his rounds delivering his meat. In the taverns and corner bars such as Klecha’s on Ray Street, the patrons downed shots to toasts of Na zdrowie! (To your health!). Even the looms at the woolen mills seemed to whirr a bit more merrily. Everyone, of course, expected the Boilermakers to return a winner.

It had been a community effort, from Mayor John Gabriel’s behind-the-scenes politicking to Art Argauer working his Florida connections, to ordinary citizens who deluged Jesse Yarborough’s office with telegrams after Art McMahon reported that the Miami coach had the final say in the selection process. Now that Garfield finally got the nod, Hy Goldberg, the Newark News columnist, said that if the committee was looking for an underdog story, it wasn’t getting short-changed in Garfield:

That’s all very unfortunate but the bitter pill for Seward is ice cream for the Garfield boys. There aren’t any Vanderbilts on the Garfield team. Most of these lads are just as much “Dead End Kids” as the Seward boys, even if they don’t live down near the East River. They are the children of mill workers and under ordinary circumstances, trips to Florida are something they read about on the society page, if, by accident, they should happen to turn back from the sport page.1

Argauer was buzzing around with preparations with the team leaving in six days on December 19. He wanted to call an immediate practice after school at half-frozen Belmont Oval, but the rain kept the team indoors for a skull session. In the meantime, Mayor Gabriel quickly arranged for subsequent practices to be held at Passaic Stadium.

“Belmont Oval’s days are over,” Gabriel declared, ever hopeful that a new stadium was forthcoming. “Why should we show our worst side to the visiting newspapermen?”

Argauer had already started working with the team for its basketball season opener in three days against Dickinson in Jersey City, where footballers Ed Hintenberger, Bill Librera, John Grembowitz, John Orlovsky and Al Yoda were in the lineup that came away with a 51-35 victory. There would be another game against Kearny the night before the planned departure. They would win that, as well, but for now, football was back as the number-one focus.

The Bergen Record’s Al Del Greco, the old Garfield Comet, headed back to his old haunt to catch up with Argauer and the boys at No. 8 school, where team manager Louis Kral reissued uniforms and equipment amid the hubbub. Most of the players, as if on a cloud, jaunted through the raindrops up Palisade Avenue from their classrooms at No. 6 to their lockers at No. 8 and engaged in a little horseplay once they got there. Argauer, Del Greco’s old Savage School classmate, was flashing an ear-to-ear smile. For once, the stern coach was letting the team have a bit of fun.

An anxious lad tugged on Del Greco’s arm.

“Look, I’m an assistant manager,” he said excitedly. “There are seven of us. We collect the uniforms, we clean the helmets, we sweep the floor. We see that these guys don’t rob the building and are we going to Miami?”

Del Greco “took a philosophical slant” on the matter and told him, “In every life, some rain must fall.”

The kid got the message.

“Nuts.”

The basement room was crowded with reporters and photographers, and Argauer was multi-tasking as he pulled on his coaching togs.

“We’ve got 500 choice seats. The Bowl seats 30,000,” he told one reporter before instructing the squad to put on their uniforms for pictures.

“There won’t be time later,” he explained.

He turned to William Capone, Board of Ed secretary and needlessly reminded him: “You had better take care of all the train and boat reservations.”

And then to William Whitehead, president of the Board of Ed, he said: “We should order forty-four new rayon jerseys right now with yellow numbers on the purple. They’ll only cost about three-fifty, and that’ll give us a swell set-up. The old jerseys will go two more years.”

Then he came back to the reporters, offering them a cigarette.

“They’re on the desk,” he said. “Honest, I think we’ll play a better game than any crowd of All Stars. Of the twenty-two All Stars picked on the World-Telly team, only two played the double wingback system (to be used by Seward Park coach Jerry Warshower). How can you get any place that way?”

Benny Babula was in demand. A photographer asked him to pose with his coach. Babula ran his finger through his wavy blonde hair and asked for a comb.

“Thinks I got all day,” the photographer whispered underneath his breath.

“Nothing the matter with your hair,” Argauer told him.

“One of you fellows hold a football,” the photographer said. So Wally Tabaka found one and threw it against the wall, nearly knocking out the camera.

The Newark Evening News spreads the news of Garfield’s Health Bowl selection on its lead sports page. Newark Public Library.

“No brains,” Argauer chided.

“Here, throw it right this time,” he said as he tossed the football back. Tabaka caught it easily, looking the ball into his hands then sent back a low spiral that Argauer missed somewhat clumsily.

The players howled.

“Now settle down,” Argauer said, getting back to business. “There are some things I want to make clear to you about this game.”

The room emptied out except for the players and coaches.

“The door closed,” Del Greco wrote. “And the assistant manager peered into the room through the keyhole.”2

Garfield already rivaled the Stingarees in enthusiasm, especially after a rather depressing occurrence that took place in Miami over the past weekend. With some free time between games, Jesse Yarborough headed out for a round of golf at Miami Springs, where the $10,000 Miami Open, featuring Byron Nelson, Sam Snead, Ralph Guldahl, Jug McSpaden and Henry Picard, would be played later that week. He asked Jay Kendrick to caddie for him as he teed it up with state official E.D. Fancher, Dr. A.F. Kasper of the Orange Bowl Committee, and Milton Chapman, managing director of the Miami Biltmore Hotel, where the Missouri Tigers stayed during the Orange Bowl.

The conversation was carefree and Yarborough, after a decent front nine, was hoping to break 90 again. They were on the 11th tee, a long par four, when Chapman took a mighty cut with his driver and hit one off the club’s toe. Kendrick was standing in the most unfortunate spot imaginable, at Chapman’s two-o’clock (just in front and to his right). He had no time to react and the golf ball hit the star lineman just under his right eye. Blood gushed from a gash requiring three stitches at nearby Jackson Memorial Hospital. Kendrick had been one of his most durable players, and now he was injured in a freak accident. The Miami Herald reported that Kendrick’s availability for the Christmas game wouldn’t be known until his X-rays were viewed.3 But the coach knew that, outside of Eldredge, there wasn’t a more valuable member of his team than Kendrick. What he didn’t know was that a big, bruising back named Benny Babula would soon be banging away at his line and that Kendrick would be needed more in this game than in any other.

The Boilermakers, meanwhile, had to make up for the week that was lost before they were finally extended the bid. They hadn’t played a game in the 19 days since the anticlimactic win over Clifton. Miami, meanwhile, never broke training while playing two huge games in that span, one for the city championship against Edison, the other for the Southern championship against Boys High. In fact, while a handful of Argauer’s two-sport athletes were already playing basketball, Eldredge and the other gridders who also played on Clyde Crabtree’s basketball team were not going to join the cage squad until football was finished.

Of course, it could work both ways. The Stingarees had been through a long season and had gotten emotionally charged up for two championship games. This was not necessarily their biggest game. The Boilermakers were, in a way, fresh and rejuvenated. This was unquestionably their biggest game, not just of the season but of their lives.

Miami’s two newspapers gave the Garfield announcement equal billing with the golf tournament and its record 217-player field, happily noting that the national championship was back on the table with the demise of the Met All Stars.

Yarborough began his preparations for the game with a light practice the same day Garfield got back to work. It was mostly a photo session. The hard practices would start the next day as he tried to gather information on Garfield. The coaches would exchange their offensive and defensive formations but not their game films. And, in that, Argauer held an advantage.

There was no way Yarborough could know anything about the strengths and weaknesses of Garfield, especially on short notice as the National Sports Council fumbled for an opponent. This left Yarborough a bit on his heels, a bit sucker-punched when it came to pre-game surveillance. Argauer, on the other hand, had a spy, of sorts. The vacationing Art McMahon attended the Stingarees’ rout of Boys High. The newsman could tell Argauer not only what plays the Stingarees used but also in what circumstances they were employed. Additionally, he imparted to Argauer reconnaissance on Eldredge’s play and how the Purples had strategically plotted to thwart the speedster.

McMahon’s wasn’t the only brain Argauer picked. Ever meticulous, he would leave no detail unattended. He phoned Charles Benson, the coach at Pompton Lakes. Benson’s team had played in Clearwater, Florida, in 1938 and lost 20-6 after defeating the Floridians, 13-7, in New Jersey in 1937.

Benson’s advice? Don’t drink the water.

That gave Argauer an idea. Garfield operated its own artesian well water works in neighboring East Paterson, where groundwater was contained in aquifers under pressure between layers of permeable rock. Residents claimed, then as now, that there was no better drinking water in New Jersey. Maybe it was because of the exotic name “Artesian,” but in any case, that was the water that would slake his players’ thirsts in Miami. But, how to get it there? Ah, convenient connections, again. Mayor Gabriel’s family ran a dairy farm. They would fill twelve forty-gallon stainless steel milk cans with artesian well water and load them onto the train.

Argauer would also get an idea of the strength and merits of Florida football from Nutley. On the same day the Boilermakers were back practicing, the Maroon Raiders were going through their first workout in Gainesville, where they would meet Suwannee High that Friday night. Suwannee High was out of Live Oak, a once rich cotton-producing area that was devastated by the boll weevil infestation of the 1920s. Farmers had since transitioned to growing tobacco as their main cash crop—that and high school football players. They grew them big and strong in Live Oak.

The Maroon Raiders were already in Florida when they opened the local papers and read that Garfield had been chosen for the Health Bowl. Now, they suddenly felt as though they were on the undercard. In fact, the Florida Times-Union reported that the entire Nutley crew was “sort of steamed” about it.

“There wasn’t a boy here today who didn’t believe his team could whip Garfield,” the paper said.4

The Maroon Raiders pointed to their edge in the comparative scores against Bloomfield and Clifton and claimed that Garfield refused to play them or to even consider it. They had also been led to believe that they were a favorite—over Garfield—to play Miami.

It had been reported by Walt Maloney of the Nutley Sun that, according to a story in the Washington Times-Herald by-lined Vincent X. Flaherty, the Health Bowl committee was about to name Nutley as the northern representative before the nod went to Seward Park. Flaherty’s source of information was McCann, the fast-talking guy who’d been keeping up everybody’s hopes. Had Maloney known that, he might not have written that, according to the “grapevine,” the bid was “as good as in Nutley coach George Stanford’s hands.”5

Disappointed by the Miami verdict, Nutley accepted readily when the invitation from the Jacksonville organizers of the Gainesville game came “like a bolt out of the blue.” Nevertheless, there seemed to be a lot of envious Maroon Raiders. Garfield was stealing their thunder.

Now, as a way of building up the Gainesville game, The Nutley Sun was calling the Suwannee team “the most feared in Florida” and reporting that Miami had turned down a challenge to play the Green Wave. Of course, the Stingarees would have had a hard time squeezing another game into their crammed schedule, especially at the end of the year. They had little to prove playing a northern Florida club after defeating Robert E. Lee, the champion of the Big Ten, the biggest football conference in Florida.6

Suwanee had won all nine of its games by a combined 321-37 score and had an All Southern guard in Rudolph Fletcher. The papers hyped the game as a battle between two hard-driving fullbacks, Frank Cardinale for Nutley and Suwannee’s Nicky Tsacrios, who scored 133 points to Cardinale’s 132 on the season. Stanford, meanwhile, proclaimed his team “ready for any schoolboy team in the country.

“The caliber of football played by high school elevens in this state (New Jersey) I think is the best of its kind,” he said. “Sure, we’re going to beat them.”7

He was right. The game wasn’t close. Nutley was the superior team.

Suwannee squandered an early opportunity when Tsacrios intercepted a lateral from Motz Buel to Cardinale, only to fumble himself with a clear field ahead of him. Later, Tsacrios was hit hard while fielding a punt in the second quarter and he fumbled again at the Green Wave 19. Cardinale finished off that drive and scored again once more before the half. The heat got to Nutley in the second half—Stanford used just three subs trying to keep the slippery Tsacrios in check—but the teams played a scoreless second half and Nutley earned a 14-0 victory, as convincing as 14-0 win could be.

Charley Bozorth, writing in the Gainesville Sun, acknowledged it a was a one-sided contest with Nutley, “working with precision and grace that was beautiful to watch.” He added: “While a power in themselves, the Suwannee eleven just couldn’t cope with the faster, harder running New Jersey team.”8

Suwannee wasn’t on the same level as Miami. Anyone who’d seen both of them play agreed. But because Nutley’s win reinforced the strength of New Jersey high school football, Argauer had to be heartened. New Jersey teams had now won five of the six games played against Florida squads since 1936, and McMahon reported from Miami that “cocky” Stingaree supporters were suddenly a bit jittery. Of course, that did not stop The Sun’s Maloney from predicting doom for Garfield based on what people were telling him down south:

Being a Northerner, we should say that the Boilermakers will annihilate the Stingarees but reports on Miami make us think the Floridians will be victorious next Monday night.

Although they were crowned Northern Jersey champions and acclaimed by many as state kings, we were not overly impressed with Garfield’s record during this season. Certainly, they do not rate as being one of the contenders for the national championship, which Miamians (but not Floridians) are calling this game.9

It turned out to be one of the last of Garfield putdowns, at least in North Jersey. For the most part, though, everyone in New Jersey, and even the metropolitan area, wished the Boilermakers well. Lodi coach Stan Piela, who starred on Garfield’s unbeaten 1924 team, even offered his team up as scrimmage fodder to Argauer the day Nutley played Suwannee. Piela knew the Boilermakers needed to knock off the cobwebs and he was happy to help his alma mater. “I’d like to see his boys in good shape for that Miami game,” he explained. Argauer called it “a gracious move” that he “appreciated very much.”

“The boys are in good condition but need some work to sharpen themselves. That long train ride to Miami isn’t going to do them any good,” he said, somewhat worriedly.

Of course, the Lodi boys couldn’t wait. When Piela told them to prepare for the scrimmage, their faces lit up with thoughts of: “Get Babula.” Big Stan quickly put a stop to that.

“Listen. If any of you boys dare to touch that big boy, I’ll personally see that you’re fried in the best olive oil. Let’s get it straight. We’re friends for a while, not enemies,” he said, firmly.

“I can’t imagine anything more terrible than Babula getting hurt in practice now,” Del Greco wrote. “Argauer would never live it down. So don’t be surprised if Benny doesn’t do any running.”10

Babula did a lot of running, in fact, and the Lodi kids never really touched him. He burst off the end for several long runs and completed a series of passes (9-of-11 in all) that left the Lodi defenders bewildered. He came out of the scrimmage unscathed. But Argauer would still be left second-guessing himself about the wisdom of accepting Piela’s offer.

Early on in the scrimmage, Wally Tabaka made a cut on a field still soggy from the previous days’ rain. He felt something go in his left knee and, although it wasn’t terribly painful, it didn’t feel right. He came off the field limping, and Argauer sent him into the grandstands next to John Grembowitz, who was sitting out the scrimmage with a staph infection on his arm. The Bergen Record’s Art Johnson reported that neither seemed to be serious, but Argauer wasn’t going to take any more risks.11 Only light practices were scheduled for the next three days before the long trip over the rails Tuesday. Team physician Dr. Erwin Reid would join them and try to nurse Tabaka’s knee back to playing condition. Hopefully, it would respond well in the warm Florida sun.

Now, each team had a major injury concern. By Sunday, it became official that Kendrick would not be available. He was taken back into Jackson Memorial and kept in a darkened room. The injury was much more serious than it first appeared.

Yarborough couldn’t believe how fortune was beginning to turn against his team.

“All year long we didn’t have an injury,” he lamented to Art McMahon. “Now Kendrick is out. (Henry) Washington is in Havana where his mother is ill. His father (Raoul F. Washington) is vice consul there. (Dick) Fauth has the flu and is in the hospital. That’s luck for you.”12

Yarborough, unsure of the status of Washington and Fauth, both tackles, suddenly had limited options. He decided to violate a cardinal rule of coaching. He changed three positions to replace one man. He moved Levin Rollins from center to right tackle and shifted Doug Craven from right tackle to Kendrick’s spot at right guard. Then, instead of using backup center Paul Louis—a future Stingaree Hall of Famer—he moved Harvey James into the pivot spot. James had played exclusively as a blocking back his one season at Miami but had been the starting center at Benedictine Military Academy. That’s also where he would make the Hall of Fame at the University of Miami and from where the Cleveland Browns would draft him.

It wasn’t as if Yarborough were throwing slugs into the lineup. He knew Kendrick was a long shot anyway and, in the least, he had two weeks to practice with the new configuration. Still, Kendrick was a major loss.

Argauer had a couple of other minor concerns. Walter Young’s mother balked at her son making the trip. The game was on Christmas when New Apostolic boys would be in church, not on the football field. Had Walter not had two older brothers, Argauer might have been missing his star left end, just recently named to at least one All State team. But Rudy and Curt ultimately convinced their mother to let Walter make the trip of his young life. She needn’t worry about him behaving himself. That much was certain.

Babula, meanwhile, was reaching his 20th birthday on Christmas Eve. That would have made him ineligible by NJSIAA bylaws. There was a brief concern that he’d be unable to play. But the Florida age limit was 21, not 20. Three Miami players had already turned 20, Harvey James in July, Charlie Burrus in November and Bucket Barnes in December.

When Argauer informed Yarborough about Babula’s age, Ole Mule said playfully, “You stick to your regulations and I’ll stick to mine.”13 He wasn’t serious, of course. There was no way organizers were going to disqualify one of their primary gate attractions. In fact, Argauer ended up bringing back Red Barrale, who turned overage just before the Bloomfield game.

By this time, Garfield was becoming a national story. Back home, the papers had to decide whether to spring to send someone to Florida to cover the game. Art McMahon was already in Miami for The Herald-News. There was no question he would remain there while Joe Lovas covered the activities in Garfield. Al Del Greco didn’t get to make the trip, much to his dismay. The Bergen Record used anonymous “special” dispatches all week. Paul Horowitz arrived in Miami shortly after the team but he was the only Newark writer there. The Star-Ledger contracted Miami Herald sports editor Everett Clay as a stringer. The New York City papers retained some interest in the game once the Met All Stars were nixed but only the New York Times staffed the game.

Then there was Hardy Whritenour. Whritenour was a 17-year-old high school student who had little interest in high school. He dreamed of becoming a sportswriter and he managed to wrangle assignments covering high school games for the Paterson News and his hometown Little Falls Herald—without pay. At the dinner table he’d regale his family with tales of the games he saw and while they humored him, they really wanted him to earn his high school diploma. They thought changing schools might help so Whritenour transferred between Passaic Valley, Paterson Central and Paterson Eastside but never did graduate.

It just so happened that the Whritenours were vacationing in St. Petersburg over the 1939 Christmas holiday. Young Hardy made his way from there to Miami to cover the game. Later in life, he’d be known as Joe Whritenour. After serving as a combat correspondent for the Stars and Stripes during World War II, he eventually settled in as the long-time sports information director at Lehigh University. He’d type out his releases in a room with his pet parakeet, who learned to mimic the sound of his fingers pounding on the keyboard.

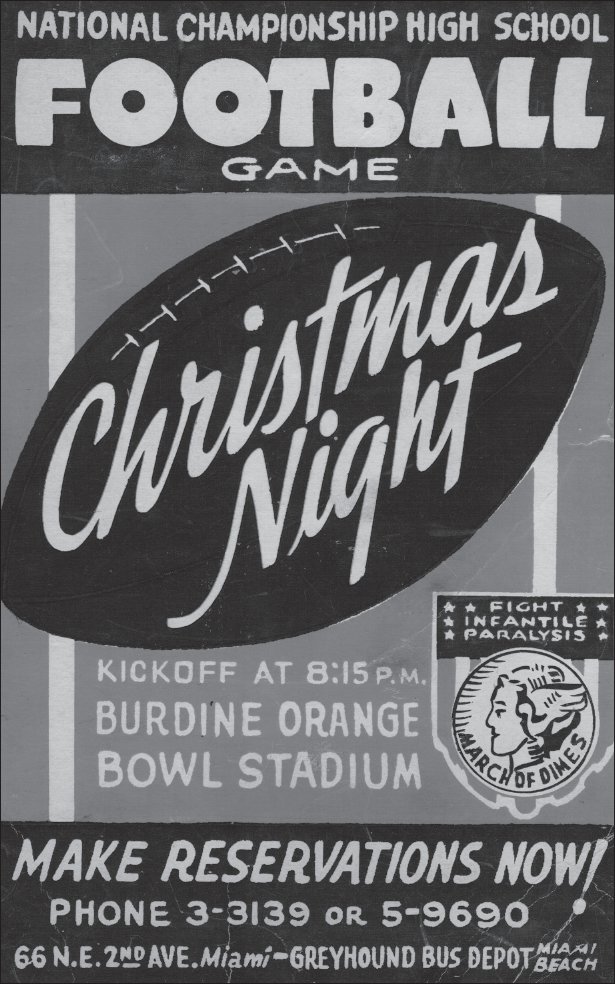

Meanwhile, the National Sports Council was cranking up the publicity machine after losing so much valuable time that could have been spent on promotion and ticket-selling. Its press releases, however, along with Associated Press wire stories, were widely picked up by newspapers around the nation, unlike the marginal attention the Louisiana game piqued.

The NSC sought to get the ball rolling just before the Seward Park announcement with a release on the game’s importance as the opening salvo in the anti-polio campaign with its focus on the four high school gridders—Jules Yon, Charley Moon, Jimmy Colton and Bill Stevens—felled by the disease since the start of the 1939 season.

“More than ever before the fight against infantile paralysis is the sports world’s own fight,” it said.14

Surely, the NSC was ready to wax poetic in press releases about Seward Park but, in Garfield, it found material to spin a new narrative in two figures—Gabriel and Babula. The mayor, never camera-shy or media unfriendly, willingly participated in the publicity campaign, even if it may have given him a little more credit than he deserved. It was all for the good of the city. If they didn’t know about Garfield before, they certainly knew now.

Considine promptly began working the “Boy Mayor” angle in his syndicated “On the Line” column in the New York Daily Mirror where he called Gabriel “the wonder boy of Jersey politics” and took one final shot at New York’s regents:

His Garfield High School football team has been selected to play Miami High in the Health Bowl game … the novel part of all this is that they are actually going—a pardonable observation on our part, inasmuch as we’ve been enthusing in print for more than a week over this and that foe for Miami High. We wrote a piece about Seward Park, the Dead End Zone Kids, and then, when they were finally sidetracked by our charitably-minded educators, we spit on our hands and did some more literary cartwheels over the selection of the World-Telegram’s All Metropolitan team. This, too, was ploughed under by our persevering pedants.

We don’t know what is the matter with New Jersey’s educational fathers. They obviously don’t believe that it hurts a boy to see a section of our great country that most of the kids could never hope to see: Florida. They apparently don’t even think it will be harmful for the Garfield boys to stop off in Washington for a look at Congress and a trip through several of the nation’s great shrines. Like Mayor La Guardia, the Jersey educators see nothing unconstitutional, or even criminal, in the kids having a great Christmas holiday.15

Considine shared the story of how Gabriel drove past a Garfield practice one day and decided to have a look. The competitive juices from his football playing days at Garfield and Drexel kicked in, and he sauntered to the middle of the field where he asked Wally Tabaka to flip him the ball.

“Let me boot one,” the mayor pleaded. He swung his leg mightily, too mightily, as a matter of fact. There was a loud ripping noise from the seat of his pants. Indeed, he would have been showing his own “worst side” to the newspapermen.

“Miami High gridmen are herewith warned not to be astounded if he comes tearing out of his flag-draped box on Christmas night, silk hat tucked under his arm, and tackles a touchdown-bound Miamian,” Considine joked.16

Indeed, at one of the pre-Miami practices at Passaic Stadium, Gabriel obliged photographers by climbing back into a gold uniform—jersey number 25—and lining up for a field goal with Babula holding. It got good play across the country as papers ran the NSC press release on the boy mayor:

Gabriel blew his horn—and the undefeated football team of Garfield High School got the bid over a score of other crack schoolboy elevens scattered through the nation.

You see, Mayor Johnny Gabriel, the 29-year-old chief executive of this thriving little industrial town, made it practically a campaign issue to get this trip and game for his high school boys. He bombarded the Florida Sports committee, the National Sports Council and various noted sports writers with phone calls, telegrams, letters and personal visits seeking the bid for the boys.17

Of course, none of that helped until the New York State Board of Education wielded its gavel but then, as now, there was no letting the facts get in the way of a good story. And there certainly was a lot of truth in the mayor’s enthusiasm for city and team.

“I just had to holler for them,” Gabriel was quoted as saying. “You see, we used to have a high juvenile delinquency rating here about five years ago and I campaigned on the platform of getting the boys out of the alleys and back into the classroom. When I got into office, I told the kids that if they concentrated on athletics and studies, life would be happier and better all around. I got them to be more interested in sports because, you know, if you’re playing a game you’re keeping out of trouble.

“Well, it worked. The accent on athletics produced two happy results: the delinquency rate dropped and the victories rose.”18

It also helped having a player like Benny Babula. And, with college scouts eyeing the Garfield flash, the press got busy hyping the game as a battle between the two blonde backs: Babula and Eldredge.

“There are a couple of blondes who will be preferred by the gentleman of the collegiate football scouting profession when Garfield High of New Jersey and Miami High of Florida get together in their high school clash on Christmas Day,” an Associated Press story barked, calling each a “ball of fire” and speculating that they could even end up on the same college team.19

Other papers ran an NSC release that portrayed Babula as another Bill DeCorrevont, the Chicago High School sensation who attracted nationwide fame two years earlier before deciding on Northwestern:

He’s got a face like a matinee idol. He’s got a powerful frame like a Tarzan. And his name sounds like a football cheer.

Benny pronounces his name to rhyme with Yale’s great cheer, “Boola-Boola” which is quite all right with Eastern experts because they’ve been pronouncing him the greatest schoolboy back in the nation.

The story added that Benny’s boosters would have none of those DeCorrevont comparisons:

“What do you mean Bud DeCorrevont the second?” they snorted. “Benny is second to no one. He is Benny Babula the First, not Bud DeCorrevont the Second.”

Actually, the anonymous writer got that wrong. “Bud” DeCorrevont was Bill’s brother, also at Northwestern. He probably took more literary license when he “quoted” Argauer regarding the college scouts:

They’ve been after him so much—at school, at practice, everywhere—that I wouldn’t be surprised to see one of them pop up right in the huddle and hand him a contract to sign and a scholarship to use.20

Papers everywhere began attaching Babula’s name to some big-time college program: Tennessee, Notre Dame, Princeton and Georgia Tech, which was playing Missouri in the Orange Bowl New Year’s Day. One story even had him heading to William and Mary with Johnny Grembowitz in a package deal. Babula himself broke the suspense while in Miami when he named Fordham as his number one choice. Eldredge, meanwhile, was said to have every college in the south on his list. He wouldn’t announce his intention to attend Georgia Tech, his brother Knox’s biggest rival—for quite some time.

Hyperbole or not, it all helped to focus national and local attention on the game—just as its organizers had hoped—and triggered a spike in ticket sales.

Back in Garfield, the city was planning a grand send-off Tuesday morning. Incredibly, when viewed through today’s lens, there was a final matter the Boilermakers needed to tend to. The school’s basketball team was scheduled to host Kearny on the eve of the Miami trip, with the Garfield squad suiting up several football players. A specter of injuries loomed.

Tabaka, naturally, didn’t play on his injured knee, and Argauer kept Babula out of the lineup in the 55-30 victory. However, five other football players participated, including Orlovsky, who scored 14 points. Joe Benigno, one of the Jewell Street boys, led the Boilermakers with 15 points.

With that, Argauer and his boys hurried home to packed bags. It was an early wake-up call. John Gabriel declared December 19 a citywide holiday, and it remains one of the most spectacular days in Garfield history.

“Schools will be deserted, factories will be slowed down, shops will be shuttered and housewives will leave the breakfast dishes soaking as all of Garfield moves to Newark to cheer the boys on their way when they board the streamline special for the sunny south,” trumpeted the Associated Press.21 And, for once, they weren’t exaggerating. Almost half the city turned out for the twelve–mile procession to Newark Penn Station to see their heroes off to Miami—more than anyone could have imagined.

An organizing committee cutting across party lines demonstrated what could be achieved with politics put aside. By 7:45 a.m., thousands were gathered around the high school on Palisade Avenue, where 15 buses, 200 private automobiles countless trucks and the pumper from Fire Company 1 were to be loaded with supporters.

One Garfield motorcycle cop, four cruisers from the Garfield police department and six more from the Bergen County police force led the entourage and cleared the way.

Banners draped across the front of the buses read: “Garfield to Miami in Fight Against Infantile Paralysis.”

School was suspended for half the day, and the entire student body of the high school and elementary schools—2,800 strong—went along for the ride. Benny’s sister Eva drove his girlfriend, Violet Frankovic.

The motorcade headed toward Passaic Street and crossed the Passaic River into Wallington, then on through the Carlton Hill section of Rutherford and into Lyndhurst, North Arlington, Kearny and Harrison, hugging the Passaic River bank south toward Newark, sirens and horns blaring, lights flashing. People craned from their front porches, and workers peered out of factory windows all along the way, cheering along with passers-by. The players opened their bus windows and waved back to some of the same fans who had rooted against them during the regular season. But they were New Jersey’s team now.

They crossed the Central Avenue Bridge in Newark and stopped at Raymond Boulevard and Broad Street, along Military Park, where they disembarked and marched down the final few blocks to the railroad station. The purple-clad Garfield High School band, with Margaret Hoving high-stepping out in front, played Garfield’s fight song. But one band wasn’t enough. Joseph F. Fitzgerald, the head of the New Jersey Committee for the Celebration of the Presidents Birthday, arranged for his hometown Carteret High School band to join the party. Gabriel told the blue-cloaked Rambler band: “If our team is as good as your band, Garfield will win by a large margin.”22

Ordinary folks off the street joined in until the throng swelled to what Newark police estimated at 10,000.

Students carrying the banners led the parade, followed by the Garfield High band. Next came Gabriel and other city officials, followed by the players and coaches, the Garfield Junior Patrol, the Carteret band, which lined either side of the entrance to the station as the players walked through and, bringing up the rear, what seemed like all of humanity.

It was a mob scene. Traffic and commerce came to a temporary halt in New Jersey’s largest city but few seemed to mind. Office workers fashioned makeshift confetti and rained it down from skyscrapers. The players must have felt like Charles Lindbergh.

At Penn Station, photographers snapped pictures of Babula, in a fashionable trench coach and tie (all the boys wore their Sunday best), shaking hands with Gabriel and Argauer.

As the flashbulbs popped, reporters asked for final comments.

“Better spirit is in the team today than I’ve ever seen,” Gabriel said. “I honestly think the team will win. By the time Babula gets through with them, he’ll be All American. The most important part is they know they can’t be beaten.”

“We’re going to do our best,” Argauer promised. “The boys are in great shape physically. If we get acclimated, we’re going to lick ’em.”

Babula was more modest.

“I hope we win,” he said. “I feel fine and so does the rest of the team.”23

The photographers wanted to get a picture of Babula with Governor Moore but he couldn’t be found. Moore had intended to deliver a prepared speech to the team just before the train pulled out. But, battling the hundreds that managed to squeeze onto the platform at Penn Station, he and Senator John G. Milton somehow got lost in the jostling throng.

They ended up on Track 3 while the team was on Track 1. In what must have seemed like a comic Laurel and Hardy short, all he could do was shout across the sets of tracks to Gabriel. The newspapers compared him to “Wrong Way” Corrigan, the aviator.

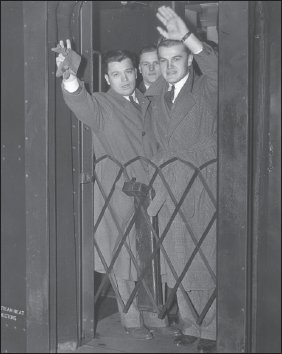

Benny Babula and John Gabriel wave good bye from the back of the Vacationer as the Garfield team pulls out of Newark Penn Station.

Courtesy Garfield Historical Society.

If the players weren’t impressed by the pandemonium breaking out at Penn Station, then they must have been when they took in the special coach train commissioned for the trip to Florida. The original plans were for the team to journey by boat, which would be docked in Miami and also serve as the team’s hotel for the week. With time running out, Garfield was instead whisked down on the Atlantic Coast Line’s Vacationer streamliner, which had been put into service only the year before. With the massive diesel engine out front, it must have seemed to the boys that they were stepping onto a space ship.

A final photo was taken of Babula and Gabriel waving from the rear of the last car to a huge ovation from the masses sending them off. Rosalyn D’Amico, Joe Tripoli’s little niece who hung out at the team practices, had a great view from atop her father’s shoulders. Violet and Eva waved frantically from the middle of the mob scene, but they weren’t sure if Benny saw them. They shrugged as the train powered up and chugged out of the station at 9:45 am for the 26-hour journey with brief stops in Washington, Richmond, Rocky Mount, Charleston, Savannah and Jacksonville.

Babula and Grembowitz sat together up front, across from Argauer and his wife Florence. The team saw her only at breakfast and at the Christmas Eve dinner. Most of the players looked excitedly out the train windows. Only two had ever been more than 100 miles away from home. Only a handful had even been to New York City. When the train got to Philadelphia, one of the players asked if they’d reached Miami.

“Settle down,” Argauer told him. It was one of his favorite phrases.

All the while, Letty Barbour, the high school songstress, entertained the team. She went from car to car and, by all reports, never stopped singing. Just a 15-year-old, she was discovered by Daily Mirror radio critic Nick Kenny, who gave her the stage name of Barbour and secured a spot for her on Major Bowes’ The Original Amateur Hour over WHN Radio in New York.

“How old are you?” the major asked her.

“Sixteen,” she fibbed, blushing.

“What do you want to be when you grow up?” he said.

“Seventeen,” she answered.

Whatever her age, Letty wowed Bowes with her rendition of God Bless America and won the segment and got a few gigs at North Jersey nightclubs. She was not just keeping the team entertained on the trip; she was to sing over the public address system, including God Bless America, before the game.

Inside the team’s special car on the Vacationer just before the train left the station en route to Miami. Starting linemen Pete Yura and Jack Boyle are in the front lower right. Assistant coach John Hollis beams in the upper left. Courtesy Estate of Angelo Miranda.

The Garfield High traveling party waves goodbye to the throng of well-wishers outside Newark Penn Station. Art Argauer, Benny Babula and Mayor John Gabriel are all visible at center.

Courtesy Estate of Angelo Miranda.

Born Letizia Barbato, she lived on Westminster Place at the edge of the Heights with her parents and paternal grandparents. Her father, Joseph, a real estate and insurance agent, was born in Marseille and her mother Giulia was born in Italy. Letty’s mother and grandmother made their own pasta and baked bread and rolls every morning, a daily treat for Letty’s friends before they walked together to school.

Apart from Letty’s warbling, the trip was uneventful. But, when they pulled into Jacksonville station at 4:15 a.m., to be switched over to the Florida East Coast tracks, the Boilermakers got their first taste of Southern hospitality. J. Frank Gough greeted them to escort them on the last six-and-one-half hours of their journey.

Gough was the president of the Greater Miami Hotel Association, a rather prestigious position in a city whose economy revolved around the tourism trade. He managed the Alcazar, where the team lodged at the hotel’s expense. Built in 1925 as the Miami skyline rose from the ground seemingly overnight, the Alcazar was one of the most lavishly accommodated hotels in town.

Gough, a full-fledged Irishman, was a Brooklyn native who started his hotel career in Illinois. Now he was a Miami fixture and man about town, frequently mentioned in Jack Bell’s newspaper columns, mostly to poke fun at his golf game. He was one of those larger-than-life figures, perfectly suited to the hospitality industry, and he was eager to show the Boilermakers the time of their lives. He would be there at their beck and call. After flying up from Miami, Gough filled in Argauer what awaited them in Miami.

Brilliant sunshine gleamed off the Vacationer as it rolled the team into Miami Depot, right on time at 11:59 a.m. The station itself wasn’t very impressive, unlike four-year-old Newark Penn Station, with its airy, vaulted waiting halls and neo-classical inspirations. Instead, Miami greeted visitors with an outdoor platform fronting a non-distinct wood-frame building that was built in 1912 and dwarfed by the 361-foot Dade County Courthouse as its backdrop. In later years, the city wasted little time in razing the structure, long-derided as a traffic-clogging blight on the city.

But, to the Garfield players in 1939, it was the gateway to heaven. There, at Miami’s sun-drenched gates, awaited a sun-tanned welcoming committee with all the accouterments of a momentous civic event. Mayor Sewell greeted Mayor Gabriel and Yarborough shook Argauer’s hand as he got off the train. The two coaches greeted each other heartily as they met for the first time—with their reputations very much preceding them.

A Movie Tone newsreel camera and radio microphones had been set up. Argauer unabashedly stepped before them, delighting in the attention, although he might have had to jostle his way to get in front of Gabriel.

“The boys are all are in good condition. Right now they need rest,” he stated authoritatively, noting that not many slept well in their seats amid the excitement of the trip.24

The advance publicity had the photographers scrambling for the mayor and Babula. They clamored for pictures of Babula and Eldredge—the two blonde bombers—together in the same frame. They got the photo-op their editors expected: lovely Health Bowl queen Martina Wilson posed between them. Davey represented the team with Harvey Comfort, who was to take over captain duties at halftime, a Miami Christmas game tradition. Comfort reached his hand out to Babula and got more than he expected—three of his fingers crushed by Babula’s vice-like handshake. When Comfort got back to his team, he warned this guy might be a problem.

Jesse Yarborough greets Art Argauer with a handshake as the Garfield team arrives at the Florida East Coast Railway station in Miami. Courtesy Garfield High School.

“That guy better not grab my hand again ’cause I’m gonna pull it right back,” Comfort said. “He’s got some strong grip.”

Babula, undoubtedly, was far gentler as he joined the arms of two Miami coeds who escorted him to a waiting car. They were part of Miami High’s all-female reception committee, described in official dispatches as “a bevy of Miami High School’s famed beauties.”25 They brought gifts of oranges, bananas and coconuts to each player.

Peeling off their overcoats to bask in the warmth of both the bevy and the climate, the Boilermakers were paraded down Flagler Street in a 50-car caravan to the sounds of the Miami High School band and the Miami Drum and Bugle Corps. Told they would be taken to the Alcazar, one puzzled player asked the coach: “Gee, are we heading for Alcatraz?”

“This seems to be the biggest thing to hit Miami,” a native told McMahon. “The Orange Bowl teams arrive, they are put in a bus and taken to their hotels. This Garfield sure must be plenty of football team to earn all this.”26

The parade swept them to the steps of the Alcazar as if by magic carpet.

The ornate lobby was bedecked in tropical motifs. It was fitted with comfortable parlor chairs around an outsized Persian rug, ringed by ferns. An expansive, towering balcony added even more grandness. Gough led them up to the tiled rooftop of the 13-story hotel— some taking the first elevator rides of their lives—where the team was treated to an opulent lunch. There they ate, hundreds of miles from frost-bitten Garfield, shaded from a blazing sun by potted palm trees, scattered around the Alcazar’s novel sun-bathing compartments.

The magnificent Alcazar Hotel, the team’s home in Miami, as seen from across Biscyane Boulevard. HistoryMiami Miami News Collection.

The team hangs out in the well-appointed lobby of the Alcazar. Red Simko, the Boilermakers’ head cheerleader, can be seen in the background after hitchhiking down to Miami. Courtesy Estate of Angelo Miranda.

Looking down, they could marvel at magnificent Biscayne Boulevard, with its three sets of royal palm islands. Directly across the thoroughfare, Bayfront Park stretched out its multi-colored hues only Florida could produce, toward the city’s sun-on-chrome waters. It was other-worldly. They had never been feted like this before and maybe never would be again. Years later, Garfield’s starting guard, Angelo Miranda, put it in perspective.

“Going to Miami was like another part of the world. We felt like we were part of the rich, the elite, when many of us were just about penniless,” he said. “A trip like this was like a fairy tale. To be put up in a hotel for two weeks, being served breakfast, lunch and dinner, was the most beautiful thing that could ever happen to us. That game gave us hope.”27

The boys chowed down, guzzling nothing but their own water, and got their room keys, four each in two-room suites. As tired as they were from the trip, the pranks began. Being typical goofy boys, they pushed the elevator buttons to stop on every floor. And they couldn’t stop phoning each other’s rooms just as modern-day teens can’t stop texting. They drove the hotel’s telephone operators crazy.

Argauer would put a stop to that later in the week when he told the boys that the hotel charged a five-cent tax for room calls.

“My gosh, I’m bankrupt,” one cried.

There was no time for a nap. Practice was next, barely four hours after their arrival. Yes, practice. Nothing like some hard work to snap their minds out of paradise. And, while some grumbled, one was surely anticipating it. Wally Tabaka had been flexing his knee with apprehension the entire trip down and, as he stepped off the train and squinted into the sun, he hoped it would be a magical elixir that would allow him to play.

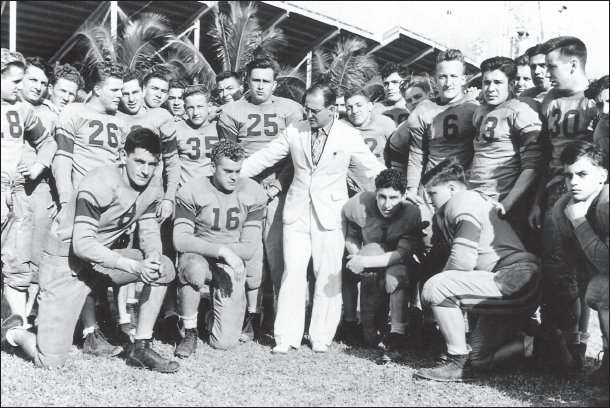

The starting lineup poses outside the Orange Bowl. Wally Tabaka (10) is pictured with John Grembowitz (33) on the line. Tabaka would be ruled out with a knee injury. Courtesy Estate of Angelo Miranda.

Art Argauer, nattily attired in a white linen suit tailored by his father, gathers his team around him outside the Orange Bowl at the Boilermakers’ first practice in Miami. Courtesy Howard Lanza.

The players really felt the Miami heat for the first time when they assembled in front of the Alcazar to board the bus to practice at Miami Field, just outside the Orange Bowl. Art McMahon had forewarned them in his reports from Miami when they were still working in the New Jersey chill.

“The weather has turned unusually warm in Miami and the Boilermakers may have to steal a leaf from the books of their grid hosts and do their practicing in shorts and bathing suits,” he wrote. Instead, Argauer had them in full gear, heavy woolen jerseys and all.

“Now is the time,” he said, to get them accustomed to the heat.

Now was also the moment for Tabaka to finally test the knee. He went off to the side with Dr. Reid and Bill Dayton, the University of Miami trainer who had been assigned to the team. Tabaka tried to loosen it up. It didn’t feel any better. He tried to push off. He couldn’t. He knew what that meant, and he started to cry openly. His teammates saw him.

Reid confided to Horowitz that Tabaka was definitely out with a torn ligament although there was no official word.28 The Miami Herald’s Everett Clay, freelancing for the Newark Star-Ledger held out hope for the readers that Garfield could “slip him” into the game for a few minutes.29 There were also scattered reports during the week that Dayton was cautiously optimistic Tabaka might play but, after some improvement, it stiffened up again on Friday night.

Tabaka stayed in uniform and posed for pictures. It was easy to see his disappointment in those shots. Garfield would miss him. While his sidelining didn’t balance the Stingarees’ loss of Kendrick, the Boilermakers nevertheless relied on Tabaka’s talents as a return man and as a complement to Babula in the backfield. He ran most of the Boilermakers’ spinner plays and, without him, the Garfield attack would be less deceptive. As a senior, he had started every one of Garfield’s 20 straight wins and was one of the team’s leaders.

It was truly a misfortune.

“Everyone felt terrible for Wally, he was so well-liked by all,” Young recalled all those years later. “It was the one bad thing about the trip.”

Argauer already expected Tabaka not to be ready and he was prepared. The good news was that John Orlovsky was healthy again after giving his shoulder a few weeks’ rest. When Orlovksy was first injured, Grembowitz came out of right guard and replaced him at right halfback. Grembowitz would now have to shift into Tabaka’s left halfback spot, though more as a blocker than runner. The Miami practice was Grembowitz’s first. The staph infection had kept him out of the all workouts up north.

As the sun bore down on them, some of the players tried to beg off, yet Argauer kept them for the next two hours. He didn’t work them particularly hard. There were lengthy warm-up exercises and what was called a signal drill, the offense going through its plays without working against a defense. Argauer told Paul Horowitz of the Newark News he wanted to tire the players out so they’d get a good night’s sleep.

He also told Horowitz he was more worried about overconfidence than the heat. The players, having scanned the Miami roster, were pleasantly surprised to note their light-weighted opponents. Indeed, the Stingaree backfield averaged only 146 pounds per man, 36 fewer pounds per man than Garfield’s backfield, with the Boilermakers enjoying an 11-pound average edge on the line.30

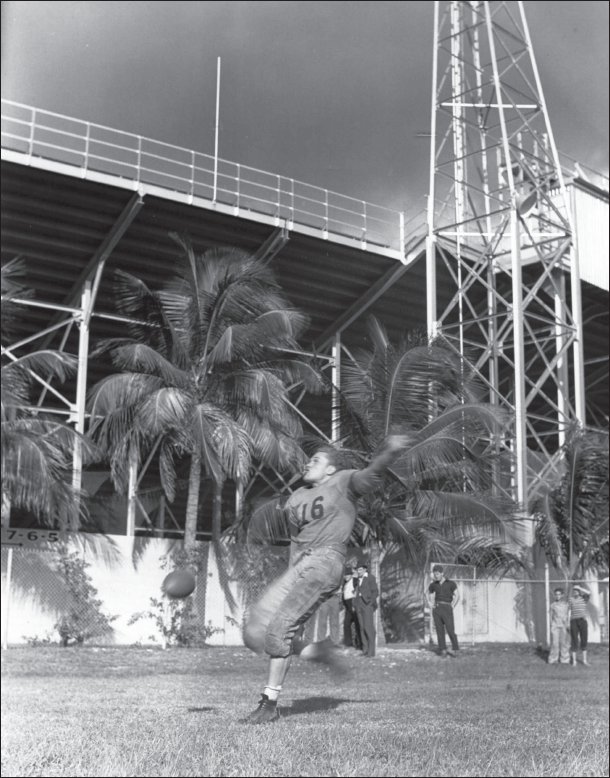

Benny Babula gets his powerful leg into a punt during a practice session outside the Orange Bowl as a few of the locals look on and marvel. Courtesy Jack DeVries.

“Benny Babula and his mates are wondering how the Miami backs can penetrate the powerful line of the Boilermakers,” Horowitz wrote.

The Boilermakers weren’t permitted to practice in the stadium in order to protect the playing field. Of course, that also meant that anyone could watch their workout. And as the Miami Herald reported, “all eyes were on ‘Boom-Boom’ Benny Babula.

“The Garfield attack looked impressive,” the Herald observed. “The big blonde runs well and can hit pass receivers both near and far downfield.”

The paper called Babula the “most troublesome back” the Stingarees would see, not only in 1939 but since the 1931 Christmas game when Andy Pilney starred for Harrison Tech of Chicago before earning fame at Notre Dame.31

Clay, on assignment for the Star-Ledger, noted that the Boilermakers “moved with smoothness and snap that cause favorable comment from spectators.”32

Babula uncorked a few long punts and the team posed for the newsreel cameras and photographers. There always seemed to be pictures to take. The starters lined up outside the Orange Bowl stands for a few group shots. Gabriel, looking snappy in a pair of white slacks, posed with the shiny new water wagon that Garfield would use for the first time. Crowed Jack Bell:

The boys from Garfield are with us! They’re a nice looking flock of kids; big and eager, and excited as they look around Miami for the first time. And with them are quite a number of New Jersey backers just as excited and just as confident the boys will have little trouble taking the Stingarees of Miami High into camp next Monday evening.

Garfield High comes with a great record. The boys, as they got off the train this noon and grinned happily, looked like good athletes. Perhaps there isn’t a better team in the East this fall. There’s no way of knowing what team, if any, is best in high school football. But this one did all asked of it, a clean record of victory no one can deny.33

Back in Garfield, the excitement continued to mount. The game would be broadcast in Florida with Ted Husing at the microphone, but none of the New York stations were paying for the hook-up. The Herald-News announced that it would stage a play-by-play reading in Garfield’s No. 8 School gymnasium. The paper assumed the cost of leasing telegraph wires from Western Union with Morse code operators at both ends transmitting the action. Advance tickets were snapped up at 15 cents each, with the proceeds going to the Garfield Athletic Association.

At least 500 fans made it down from Garfield to Miami. That’s how many tickets Gabriel ordered. But, after they had been mailed to New Jersey for sale, it was quickly noticed that the seats were on Miami’s side of the field.

“This would have caused a furious renewal of the War Between the States and made the Health Bowl something else,” reported the wires. “But Arthur Suskind Jr. who is handling this detail of the game for the National Sports Council hurriedly wired Miami for 500 different tickets and thus made certain that the blocking and tackling will be confined to the gridiron.”

The first Garfield rooters, around 250, made the trip with the team on three cars that were added to the special train. Another fan train left the next day, and still more arrived on the Havana Express train Friday. Other stragglers travelled by car, including a few 12- and 15-car caravans. Some even made it down by thumb.

Bill Wagnecz’s father, George, had just purchased a 1939-model Plymouth. He wanted to drive the family down in it but he couldn’t get out of work. Instead, six family members and Bill’s girlfriend (later wife) Marguerite Comment squeezed into the sedan for the three-day journey. Another uncle, John, wouldn’t have fit so he took one of the chartered buses instead.

“It was myself, my mother (Julia), my older brother Ernest, my Aunt Anna and Uncle George (Roman) and their eight-year-old son, George, plus Marguerite,” remembered Bill’s sister, Eleanor, just eight at the time. “We all crammed in there and when I say crammed, I mean it. My mom and my aunt were a little on the heavy side. I sat on my mother’s lap most of the time and my cousin sat on his mother’s lap. Poor Marguerite was squeezed in between us in the back seat.”

Ernest was behind the wheel most of the time but Uncle George was a bit of a backseat driver. He got his turn in South Carolina, where a motorcycle cop noticed the New Jersey license plate and chased them down for speeding. They all had to traipse down to the police station to pay the fine. Uncle George didn’t drive again—from either seat. It remained a family joke for generations.

R. Sal Barrale, clerk to the Garfield Board of Assessors and the brother of Red Barrale, was already in Florida on honeymoon with his new bride Edythe. He found out about the Garfield bid when he bought a paper in Jacksonville to shut up a pushy newsboy. The Barrales, as planned, took in the Nutley game in Gainesville before heading to Miami to catch up with the team.

Lou Mallia, 23, was temporarily unemployed. He had a ’37 Pontiac sedan. He headed down with three of his buddies and, when one begged him to take his friend, he reluctantly agreed, so he crammed the car with five guys. Mallia did all the driving. He had bought a trip plan from the Continental Oil gas station to keep track of expenses, but was kind of sore when his buddies didn’t pick up their share. They went straight through to Savannah before stopping to sleep and got to Miami the next day.

“When we finally got to the Alcazar, those guys were living it up,” he recalled many years later.

Mallia’s bunch found less luxurious quarters.

“We stayed in a so-called hotel with the bathroom down the hall. A so-called hotel,” he repeated. “All they had in the room was a sink to wash your face. It may have been one or two dollars a night.”

Another enterprising bunch from the Garfield Indians athletic club chipped in to buy a ’31 jalopy, a wreck that guzzled gas at the rate of nine miles a gallon. They made it as far as South Carolina before blowing a tire in the middle of the night. They couldn’t see, so they set one of the spares on fire in order to change the tire. Off they went once more until the car started to buck. It gave out for good in Brunswick, Georgia, where they sold it for $11 and took a bus the rest of the way.

Red Simko hitchhiked down on his own, leaving ahead of the team on Monday and arriving Friday. Garfield’s top cheerleader and candyman got as far as Richmond, Virginia, where he was stranded for 10 hours before an FBI agent gave him a lift into Jacksonville. Garfield fans driving south saw him on the side of the road outside Jacksonville and took him the rest of the way. Simko said the longest ride he received was 900 miles. He bragged that the entire trip cost him $4.35.

Bunches of Garfield High students followed Simko’s lead.

At one point, Gabriel was asked, “What do you think the Board of Education will do about these hitchhikers who are skipping school to see the game?”

“What do you think?” he replied with a wink and a smile. Suffice it to say the New York State Board of Education would not have approved so cavalierly.

Somewhat unfortunately for the players, most of those kids ended up freeloading at the Alcazar.

“I remember going up to our room and finding a dozen of the guys from back home in it,” Bill Librera said at the team’s 50th reunion. “After a while I asked them where they were staying and they said, ‘With you … look at this room. And guys, when you go to breakfast in the morning bring us back rolls, because we’re short of money.’”34

It wasn’t as an adventurous week for the Miami players, who were all at home. The only difference for them was that they were on Christmas vacation. Yarborough held his last hard scrimmage the Friday before. He practiced every morning at 9:30 in the days leading up to the game to beat the heat, but the sessions lasted just over an hour. It had been a long season. One day the entire team met for a photo session at the school. Eldredge, Koesy, Comfort and Red Mathews posed for campy publicity shots on Miami Beach. Just in their helmets and bathing trunks, they feigned to prepare to receive a hike delivered by a lovely young woman. As Jack Bell noted:

In a Herald-News promotional photo, Art Argauer and the boys take in the paper’s account of their trip south. Showing interest, from left to right, are Ed Hintenberger, Benny Babula, Angelo Miranda, John Orlovsky and John Grembowitz. Courtesy Howard Lanza.

To Col. Jess Yarborough and his boys this Christmas day game is old stuff. They’ve been playing it since 1929 and are going about their job of getting ready with little fanfare. It’s just another football game to them for if ever a high school team had poise it’s the 1939 Stingarees.35

That may have been. But, for once, the Stingarees weren’t playing a team that held them in awe. What’s more, they knew very little about the makeup of Garfield’s team, apart from the barrage of publicity surrounding Babula and the formations Argauer sent them in an exchange with Yarborough. There was no film available and, unlike Argauer, who had Art McMahon’s report from the Boys High game, Yarborough knew no one who had seen the Boilermakers in action. Interestingly, Yarborough practiced with a seven-man defensive line to stop the big back in his tracks and perhaps make up for the penetration that Kendrick would have given them. But the formation also opened his team up to reverses and end-arounds. Offensively, Miami concentrated on the passing game, perhaps rationalizing that, without Kendrick, the running game would be less effective.

Things were going just as Argauer had planned—even his late Wednesday practice, the ploy to tire his boys out. Many of them slept through breakfast the next day. They were on a tight regimen down to the minute, designed to fix their minds on the business at hand with two workouts scheduled on certain days. There were three meals a day on the roof of the Alcazar and, at one o’clock, Argauer read to them greetings and best wishes from town residents published in the Garfield Guardian. They returned a message that they were “striving to bring victory and glory to Garfield.”

On Thursday, the team’s first full day in Miami, organizers took them on a sightseeing tour of Miami Beach just before practice, where Argauer began to install a game plan geared to stopping Miami’s high-flying offense. The philosophy was exactly the reverse of Jesse Yarborough’s. He was bringing men up to the line to stop Babula. Argauer was moving them further back to stop Eldredge.

At the team’s first practice, the papers dutifully reported that Argauer used a standard 6-2-2-1 defensive formation. That suited Argauer just fine, knowing that Yarborough would be anxious for any tidbits, and that he had no intention of sticking with a six-man line.

Paul Horowitz’ story in Friday’s Newark News offered the first hint of Argauer’s real strategy.

“Pass defense was stressed in yesterday’s drill, which lasted an hour and 45 minutes,” Horowitz reported. “Coach Argauer believes the Southerners will fill the air with passes and he is toying with a defensive setup that probably will surprise the Miamians.”

The surprise setup was a five-man line with Grembowitz as a sort of rover. Not only would this put more men in the secondary if Miami went to the air, but it would also work against Eldredge’s breakaway ability.

McMahon saw that first-hand in the Boys game and again while watching the Stingarees’ scrimmage the previous Friday. The description of Miami’s “short punt” offense that he provided in The Herald-News was probably quite similar to the scouting report he gave Argauer:

The plays are diversified but the pet ground gainer is an off-tackle smash that requires breathless speed and expert blocking. Dave Eldredge is a ball of lightning and much of his success is due to the speed with which he reaches the scrimmage line. Garfield will have to keep a hair trigger defense to keep him under control.

It was useless, Argauer thought, to have an extra man at the line of scrimmage given that Eldredge did his real damage once he got past the scrimmage line. So, Argauer would array six of his men in a formation that maintained a numerical advantage over Eldredge’s quick-footed downfield blockers. They were also instructed not to go at Eldredge straight on but rather at angles to limit the effectiveness of Eldredge’s jukes and fakes. Here is where Grembowitz would be key. While he wasn’t as fast as Eldredge, he was smart. He knew how to take away space, and he was relentless. He never gave up on a play.

As luck would have it, neither Miami paper had anyone at the Boilermakers’ Thursday practice. Everyone, even Mayor Gabriel, along with his mother, whom he brought along, seemed to be at the opening of Tropical Park. That was the news of the day. Both the News and Herald relied on the daily press release, which still had Garfield in a six-man defensive line. Unless Yarborough had a spy at practice, he was unaware that Argauer was scheming otherwise. Argauer had one day to practice in relative seclusion. And since the practice was more a mental one—meticulously going over and over the new formation—he could overlook the lethargy, which was evident to observers.

As Horowitz wrote, “Two days of practice under a hot Florida sun has caused the players … to show signs of sluggishness.”

McMahon, obviously watching the same workout, went even further.36

“Miami’s weather has been as important as Miami’s football team to Garfield High’s knights of the gridiron,” McMahon wrote. “Staging their second drill in this semi-tropical air, the Jersey Boilermakers plainly showed the effects of the hot sun. Here it is mid-July in Jersey and the boys just can’t get football conscious. They were sluggish, peevish and out-and-out unimpressive.”37

There was a good reason for that. Dayton was advising the Boilermakers not to swallow liquids during practice.

“No matter how much of their imported water they drink, they sweat it right out,” McMahon reported. “Their blood has thinned in the normal 48-hour transition and the natural slow gait that attacks all who have trapped Florida sand in their shoes has caught up with them.”38

That was the popular belief then. So the Boilermakers would go to their water wagon, swish their artesian well water around to wet their whistles and spit it out. Rather than combatting the dehydration with hydration, Dayton suggested that Argauer give two 10-grain salt tablets to each player after each drill.

“The salt treatment has done wonders to offset devitalization of the players in this climate,” Horowitz explained, although McMahon noted sarcastically, “a glance at the Hurricane record is hardly a strong recommendation for the practice.

“Anyway,” McMahon continued. “Argauer plans to try the tablets in an effort to restore some of the Jersey vim and vigor to his weary Boilermakers.”

Off the practice field, the intrigue began to build between the two coaches. Argauer worried about playing at night. Remember, he had begged off a return game under the lights against East Rutherford after the nearly losing to the Wildcats in a poorly-lit night game at Passaic Stadium in 1938. He vowed at the time it would be the last night game his team would play.

Miami had a distinct advantage, of course. The Stingarees played every one of their home games and one of their two road games under the lights.

At first, Argauer asked that the game be played with a white ball. Yarborough refused to even use the white ball for just one half. The white paint made the ball too slippery, he said. Argauer’s request to practice Friday night in the Orange Bowl was also turned down on grounds that the Boilermakers would rip up the playing field. He got around that by scheduling a Friday night practice at Stranahan Field in Fort Lauderdale. The people up the coast were happy to comply. Their civic rivalry with Miami was fierce and they saw this as a chance to stick it to them.

Yarborough didn’t attempt to prevent that. He had other concerns that threatened the very playing of the game.

Garfield was being lodged, fed and feted in typical Miami style, all expenses paid at a total cost of $2,000, with Frank Gough’s Alcazar slicing that in half by putting up the team. What were the Stingarees getting out of it? Every other Christmas game put money into the athletic department’s coffers. Now they were expected to play the game for nothing—and that’s not what Miami High had agreed to when Robert Dill and his group met with Miami High and Edison High authorities back in November.

According to Jack Bell, who was present at the meeting, Dill was informed that both Miami and Edison already played charity games. Edison played Greenwood, Mississippi, for the Lions Club fund and Miami played Boys High for the Kiwanis fund for underprivileged children. Miami would donate the total take of $3,231.70 for that game.

Dill was amenable, and city officials at the meeting said they would ensure the home team would receive a fair share. Dill asked Miami principal W.R. Thomas how much the Stingarees usually netted playing on Christmas.

“Anywhere from $1,500 to $3,500,” Thomas said.

“Oh,” Dill replied. “We won’t have any trouble getting together on the matter.”

As Bell noted, the Miami High officials agreed without even a handshake. “How dumb they were,” Bell wrote.

At the time, no one gave it a thought; most all had assumed they had a potential gold mine in Seward Park. Whether that was true or not, Dill convinced the National Sports Council that Miamians would fill the stadium and assured the Miamians that New Yorkers would scoop up boxes at $200 apiece. Meanwhile, the press was being told that every cent of the proceeds would go to fight infantile paralysis.

It wasn’t until Garfield became the opponent that Miami High was told that the state chairman of the infantile paralysis committee still assumed Miami would play gratis. The Miami High School athletic council hastily met and voted to request $3,000. Dill, after all, had previously told Thomas not to take less than the school would usually profit on the game.

That was, however, when Dill had dreams of an $80,000 gate. Then, when it appeared ticket sales lagged—largely due to the botched Seward Park-Met All Star affair—even a $20,000 gate seemed unlikely despite the Sports Council’s best efforts to whip up interest.

So, in an all-out effort, the Sports Council began promoting the game with a special 15-minute spot on the CBS Radio Network. Featuring Kate Smith, it was aired coast-to-coast. The papers ran pictures of Sam Snead (who had just come from behind to win the $2,500 first prize at the Miami Open) and former heavyweight champ Jack Dempsey (who ran a restaurant and bar in Miami Beach) purchasing boxes for the game. However, neither could attend: Dempsey headed to the Philippines to referee a fight and Snead went back to West Virginia with a toothache.

A ticket office was set up in the lobby level of the beautiful new DuPont Building. The window to Flagler Street was plastered with pictures of both teams. Considine had written that once word got out about Babula, “ticket sales leaped.” But regular Miamians, who were being asked to attend a third straight big high school game, were more confused than enthused by the organizational mismanagement.

Now Miami High was told: “Sorry, you’re not taking anything out of the pot.” And, when the state infantile paralysis representative reminded the city of Miami that it had guaranteed the school $1,500, the city fathers hemmed and hawed.

“The old buck looked like a football handled by Sammy Baugh,” Bell later wrote. “There were definite threats to call off the game, which I’m sure weren’t as serious as they sounded.”39

As it was since the start, no one seemed to be in charge. And that’s how the matter was left as game day approached—just hanging like the moon over the horizon. Nevertheless, it remained very much on Yarborough’s mind. He was, and legitimately so, annoyed.

With a Machiavellian touch, Yarborough waited until two days before the game to press the issue and threatened not to take the field unless the high school was compensated. The city of Miami now agreed to turn over to the Stingaree coffers the money it received for the stadium rental and concessions—about $1,500.

Of course, Garfield’s athletic treasury wasn’t profiting from the trip, either. Art McMahon estimated that the Boilermakers would have netted at least $4,000 from a post-season showdown against either Vineland, Nutley or Passaic. But he also noted that the season’s profits were already at $7,000 after the big paydays against Passaic and Bloomfield.

“Coach Art Argauer and other school officials favor the Miami trip as a reward for the players,” McMahon wrote when Garfield was considering its options. “They don’t feel that the squad should be called upon to increase the treasury’s football booty with a postseason tilt here but if the opportunity to take a pleasant journey to the land of oranges and sunshine is offered as bait, that’s barking right up the palm tree.”40

Garfield’s benefits from the game came in the form of nationwide publicity and in the once-in-a-lifetime experiences of the players. Friday, three days before the game, they were treated to their most enjoyable outing of the week, a two-hour boat ride down Biscayne Bay on the Silver Moon. The excursion boat was famous for midnight cruises and about a month earlier, made news when Ray Hamilton, a 23-year-old visitor from Buffalo, declared, “this boat’s too slow for me,” and dove into the water three miles from shore. Feared drowned, he showed up at the hotel later that day. He was an expert swimmer.

There were no such theatrics on Garfield’s voyage but it was quite an affair. Gabriel was on hand again and, as the ever-present photographers snapped away, he was greeted at the gangplank by the ship’s captain whose boat was plastered with posters for the game. A Miami High coed awaited each player and, as a full band played away, several danced up a storm. Nearly everyone knew how to dance in those days. It was the path to romance, and they had stars in their eyes as they cruised along the bay. There’s a picture of Babula and Grembowitz relaxing with the girls. They looked like movie stars at a Hollywood party.

John Gabriel shakes hands with the captain of the Silver Moon as the team boards, drawing interest from some of the local kids. Courtesy Estate of Angelo Miranda.

The two lovely Miami High coeds assigned to keep John Grembowitz and Benny Babula entertained on the boat trip. With Babula is Martina Wilson, the Health Bowl queen. Courtesy Estate of Angelo Miranda.

The Silver Moon, adorned with game posters, is fully loaded with the Garfield team as it prepares to leave the dock. Courtesy Estate of Angelo Miranda.

Angelo Miranda twirls his girl around the Silver Moon dance floor to a live orchestra as Leonard Macaluso bashfully holds his girl close. Martina Wilson has her arms around Benny Babula in the background. Courtesy Estate of Angelo Miranda.

Letty Barbour relaxes with Mayor John Gabriel and his mother aboard the Silver Moon cruise. Courtesy Estate of Angelo Miranda.

Earlier, several Garfield players joined several Miami players in a visit to Jackson Memorial Hospital, where they were photographed visiting young polio victims and, then Jay Kendrick, who wore a huge bandage over his right eye. Argauer sent his reserves.

Back at the Alcazar, Frank Gough was fully enjoying his guests, even the moochers. He loved Letty Barbour’s voice and set her up with a gig at the Eight O’clock Club on one night and to accompany the hotel band on another. One afternoon, he escorted her into the News Tower, where she wowed the staff with “South of the Border” and got her picture taken for the next day’s paper.

Jack Bell called Letty “Little Personality” and noted, “blasé sportswriters, photographers and even Smiley quit her beloved switchboard, paused and listened. After she left the evening was spent in attempts to speak Mexican and wonderment that the high-salaried crew staging the infantile paralysis fund hadn’t discovered Letty days agone.”41

The Boilermakers’ Friday night practice would be their best of the week. The night air was crisp. The Boilermakers reveled in it. They had finally been unshackled from the day’s 85-degree heat. Even after an earlier two-hour workout under the sun at Miami Field, they were refreshed and active. They opened the windows on the bus ride up Rt. 1 to Fort Lauderdale and, when they arrived at Stranahan Field, a big crowd awaited them, anxious to confirm if Babula indeed had a frame like Tarzan. He didn’t disappoint.

Wrote Horowitz: “Benny Babula’s passing and kicking so impressed a small group of Fort Lauderdale residents, one was heard to remark, ‘Gee! They ought to play Miami University, not Miami High.’”42

Similarly, the headline over McMahon’s story read, “Babula’s passing Makes ’em Sit Up.” McMahon called it a “flashy workout” and wrote that Garfield, “found in the brisk air of this place at night the tonic it needed.43

“The air was sharp last night and there is no question that if the weather gods treat Garfield that way Monday, the Boilermakers’ chances of victory will be enhanced,” he said.

It was pretty much impossible to quantify those chances because of both the variables and the unknowns. The Associated Press made Garfield the favorite because of the 17-pound per-man weight advantage it took into the game. The Stingarees’ backfield, with Jason Koesy, at 150 pounds and its biggest starter, was the lightest the Boilermakers had faced. Both the Miami Herald and Miami News had it too close to call. The Bergen Record, which did not have a man in Miami, gave the clearest insight into the locals’ thought process in a story headlined “Jersey Champions Have Few Backers”, which was written anonymously as a special to the paper:

In spite of their 20-game winning streak, Garfield High School’s Boilermakers will be underdogs when they oppose the Miami High Stingarees.

Miami High School’s backers are offering odds that vary from 6-5 to 8-5. Few wagers have been made.

Except for Babula, sportswriters here haven’t a high opinion of the Garfield eleven. All of them are stringing along with the Miami team. The Miami scribes figure the Stingarees will win on speed and deception.44

It was interesting that Argauer used a white ball that night in Fort Lauderdale. The New Jersey writers all reported that he had convinced Yarborough to approve it after the Miami coach learned that Garfield wore yellow-colored jerseys that, Argauer told him, would blend in with a regular football. Those reports were wrong. The only white ball in the game was a souvenir ball that was used for autographs. However, both Horowitz and McMahon reported that the lightweight purple jerseys Argauer had ordered had come in. Argauer said he would use them at least one period unless it was a cool evening.

“The Boilermakers have been complaining in the afternoon workouts that their suits are too heavy, the sweaters especially becoming sweat-clogged after brief periods of practice,” Horowitz noted.45

The Fort Lauderdale excursion was noteworthy for another reason other than the cooler temperatures. Nearby was another reminder of the war in Europe. The SS Arauca, an unarmed Hamburg-American freighter flying the Nazi flag on its maiden voyage, was docked in Port Everglades, where it would remain for the next 20 months as Washington walked a diplomatic tightrope with Berlin.