The environmental cost of human inequality

![]()

The more unequal a society is, the more it damages its environment, which eventually collapses. This is clear from archeological as well as modern evidence. However, more equal societies can enjoy prosperous and fulfilling lives with little or no impact. ‘Blame games’ have dominated the debate until now – targeting the rich, or the poor, or human nature itself. But our real enemy is the inequality that creates rich and poor – and turns technological progress into an arms race.

To a conventional ‘hard-headed realist’, the human suffering described in the last chapter is water off a duck’s back. The idea that life is a tough business has been thoroughly drummed into many people. But what if all this allegedly healthy rough-and-tumble is what’s wrecking the planet?

We have seen that inequality is bad for technological progress and bad for human beings. But if it is also, by exactly the same token, disastrous for the environment, then human well-being suddenly becomes a matter of major concern even for ‘hard headed realists’. A simple if challenging remedy offers itself as an alternative to all the hand-wringing, finger-pointing and head-scratching: to reduce impact, reduce inequality.

ARE THE RICH DESTROYING THE EARTH?

It used to be argued that, although the wealth of the rich might be morally objectionable, it is a distraction because no matter how wealthy they are, sharing their wealth among the whole population would spread it too thin to make much difference. Even some leftwing economists have argued along those lines.1

But this misses the real point: when a few people control most of the wealth, the whole dynamics of a society change, affecting the way people live their lives, and the impact they collectively have on their environment.

We now have strong evidence from a great many sources that the lion’s share of any society’s impact is caused by its wealthiest members, and a less equal society as a whole has a higher environmental impact than a more equal one does.

An Oxford University study in 2006 found that 61 per cent of all travel emissions came from individuals in the top 20 per cent, while only 1 per cent of emissions came from those in the bottom 20 per cent.2 Similar figures are frequently cited for the global situation. The social geographer Danny Dorling reckons that:

it is almost certainly an underestimate to claim that the richest 10th of the world’s population have a greater negative environmental impact than all the rest put together… And, of the richest 10th of the world’s population, the richest 10th [the top 1 per cent] consume more, even than the other half a billion or so affluent.3

Their disproportionate impact is explained not by their wealth per se, but their wealth relative to the rest of the population. In fact, the very meaning of wealth is distorted in an unequal society.

Data from the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) in its biennial Living Planet Reports support the idea that global environmental impact is connected with inequality. The WWF developed the concept of the ‘Global Hectare’ (GHa) to measure how much of the planet each country requires to sustain itself at its current level of consumption. To be sustainable, each citizen would need no more than 2.1 GHa but, in 2005, US citizens were using 9.4 GHa each.4

This could easily be taken to mean that improved living standards inevitably carry an environmental cost, but the WWF’s 2006 Living Planet Report revealed an important new twist by comparing each country’s ecological impact with its quality of life, as measured by the UN’s Human Development Index (HDI). It showed that many countries with acceptable HDIs had much lower impacts than the US (and we will see more detail on this below). One of these, Cuba, made headlines briefly in the world’s media: it was the only country in the world to achieve environmental sustainability and good lives for its people, with a footprint per citizen of just 1.8 GHa. It was even regenerating forests that had been destroyed in the days of Columbus. Cuba is of course (or at least still was in 2006) one of the world’s most equal countries.

Cuba’s huge achievements were recorded in the immediate aftermath of what should have been a catastrophe: the loss of its major export market and its main source of oil, fertilizer, medical technology, training, drugs and even soaps and disinfectants, after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1989. Brian Pollitt, a Glasgow academic who works with Scottish Medical Aid for Cuba, has written:

The most important single factor is that despite dramatic falls in State income of all kinds during the worst years of the 1990s, the maintenance of health provision, together with education, was an official national priority… Cuban State expenditure on health was $937.4 million in 1990 and $1,210 million in 1996. In telling contrast, expenditure on defence and public order over the same years fell from $1,149 million to $725 million.5

The fall in military spending is indeed telling – in at least three ways. First, military activities account for a fifth of all global environmental degradation6 – so this of itself must have helped Cuba ‘go green’. Second, militaries are quintessentially elitist organizations, and accrete around themselves larger ‘penumbras’ of important people, who supply, advise, admire and represent them in government, and this affects a country’s respect system as well as its distribution of resources. Third, to reduce one’s armed forces so significantly at such a moment of extraordinary vulnerability – Cuba had lost its main military ally and was now surviving, under blockade, on the very doorstep of its avowed enemy, which happened to be the world’s largest military power – flies in the face of conventional wisdom, and rather calls it into question.

For those who are wary of accepting a Latin American socialist example, Finland also offers a similar example of very high health and educational achievements, low spending on military, police and prisons, very low carbon emissions – and very low inequality. Pasi Sahlberg has explained that Finland’s politics were shaped by two major economic crises – in the 1970s and again in the 1990s – leading to an all-party commitment to solidaristic policies.7 He writes: ‘a crisis can spark the survival spirit that leads to better solutions to acute problems than a normal situation would.’ These included scrapping selection in schools, abolishing private education of all forms and making it illegal, and a commitment to free education, including tertiary education, for everyone, wherever they lived. It was also decided to give teachers much greater autonomy, and scrap the schools inspectorate – of which Sahlberg had been Director. He instead became Finland’s proselytizing education ambassador.8

Some people argue: ‘Ah, but Finland is a rich country.’ Not so: it has few natural resources apart from timber and it has never had an empire; the Finns had realized that their main resources had to be themselves and their children. The other objection is ‘Ah, but the Finns are ethnically homogeneous: solidarity comes easily to them.’ Again, not so. Finland is fairly diverse. It has several official languages, a substantial aboriginal population – the traditionally stigmatized Sami – plus Swedes, Russians, Romani, Arabic-speakers, Vietnamese, and others.

Measuring the impact of capitalist nations is likely to under-report the situation if one looks only at what is happening within their national borders, because their basic dynamic involves externalizing high-impact activities. But, even so, general patterns are observable – and the figures in the table below, based on the polite convention that nations do their own dirty work, are certainly on the conservative side.

The WWF’s reports consistently show that countries, such as the Scandinavian ones and Japan, that are almost as wealthy in GDP per capita terms as the US, but which are more equal, have lower ecological impacts. Danny Dorling has found that the correlation between European countries’ inequality and their ecological footprints may be even closer than the reports suggest, when each country’s usable land area is added into the equation.

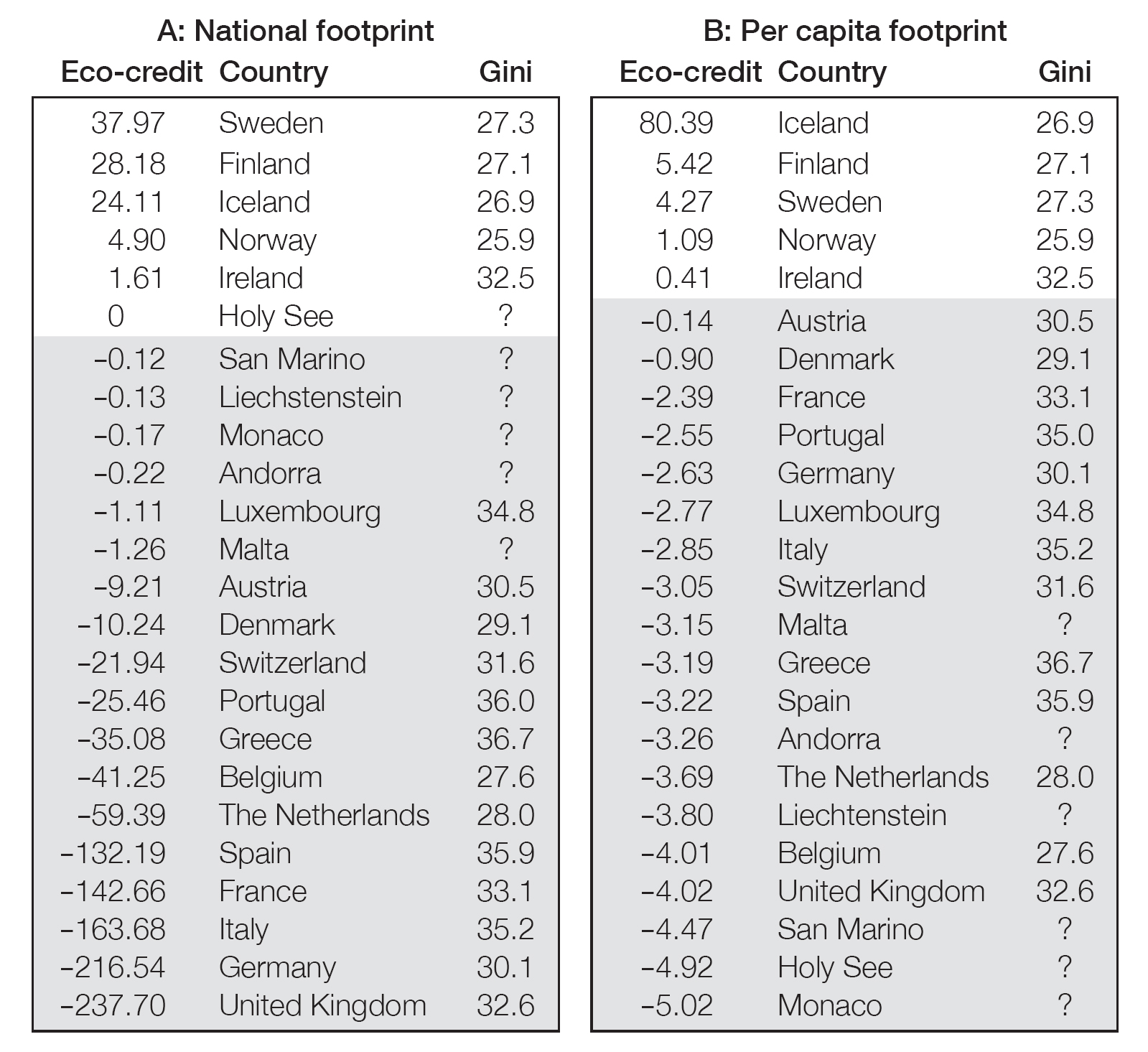

Table 1 shows the ‘eco-credit’ (or debt) of 24 countries, and their Gini coefficients of income inequality, where available. It shows the impact of the country as a whole (1A) and per capita (1B). Nearly all the countries that are in ‘eco-credit’ are the more equal ones — especially when calculated per capita. It is interesting that some of the most resource-hungry countries are also the more secretive ones, with no readily accessible wealth and income data.

Table 1 National and per-capita ecological credit or deficit

Eco-credit or deficit is shown in millions of global hectares for a selection of European countries, adjusted from WWF 2006 data by Danny Dorling to include each country’s own biocapacity (usable land area). The unshaded countries at the top have more capacity than they are using, especially when calculated per capita (B).

The Gini coefficients are from the World Bank and are based on 0 = perfect equality and 100 = perfect inequality.

A similar relationship can be seen at regional and local level. Jim Boyce, co-director of the Political Economy Research Institute (PERI) at the University of Massachusetts, has found that the most unequal US states (such as Tennessee, Alabama and Mississippi) contain more environmental degradation than do more egalitarian states (such as Minnesota, Maine and Wisconsin), in direct relation to their level of inequality. The relationship holds up whether you measure this by income differences, or by distribution of political power – indicated by voter participation, access to education and healthcare, and tax fairness. This is because:

In practice, many environmental costs are localized, rather than being uniformly distributed across space. This makes it possible for those who are relatively wealthy and powerful to distance themselves from environmental harm caused by economic activities…. Within a metropolitan area, for example, the wealthy can afford to live in neighborhoods with cleaner air and more environmental amenities. Furthermore, sometimes there are private substitutes for public environmental quality. In urban India, for instance, where public water supplies are often contaminated, the upper and middle classes can afford to consume bottled water. The poor cannot. In such cases, because access to private substitutes is based on ability to pay, again the rich are better able to avoid environmental harm.9

He, too, finds that the same phenomenon is observable globally: countries with a more equitable balance of power (evidenced by such things as civil rights and adult literacy) also tend to have better environmental quality – even when controlling for factors like per-capita income, which might have affected the result. He concludes that ‘People are not like pondweed. How we treat the natural environment depends on how we treat each other’.10

Human environmental impacts have increased over time, as human inequality has increased. Figures from the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) show that atmospheric CO2 equivalents increased more than twice as fast during 1995-2004 (the first 10 years of the World Trade Organization’s existence, when the brakes really came off neoliberal growth and worldwide inequality soared) as during 1970-94.11

INEQUALITY TURNS HUMANS INTO A GEOLOGICAL FORCE

In 1992, a science writer and ecologist, Andy Revkin, wrote: ‘We are entering an age that might someday be referred to as, say, the Anthropocene. After all, it is a geological age of our own making.’12

In 2008, the Geological Society of London’s Stratigraphy Commission (the global authority on these matters) agreed to adopt Revkin’s suggestion and make the Anthropocene designation official.13 The Holocene period (the period of climate stability since the end of the last ice age, about 10,000 years ago) is officially over and we are now in ‘a stratigraphical interval without close parallel in the last several million years’.

But this situation has been longer in the making than we generally realize. Archeology tells us that the problems of ecological collapse we’re now facing were already evident when the first class-based societies appeared in the eastern Mediterranean around the third millennium BCE, and in the Americas. Those vanished societies should be ‘warnings from history’: their inequality made them ‘self-extinguishing’, for reasons explained by Deborah Rogers’ work, described in Chapter 2. The heavy material demands that social inequality creates (for palaces, temples and so on) eventually sucked the life out of the ecosystems on which they depended, they were unable for one reason or another to draw in new resources from beyond their borders, and they collapsed. This was the fate of many of the states of early antiquity in the Fertile Crescent in present-day Iraq and Syria, and of the Mayan empire of pre-Columbian America in the ninth century CE. The events described in Chapter 2 suggest that Japan may have escaped a similar fate in 1600.

The Mayan empire fell victim to droughts caused by deforestation which, it is now apparent, was caused by the huge demand for charcoal to burn lime, required for the construction of palaces and temples. Thomas Sever, co-author of a recent study of the Mayan deforestation, calculated that 20 trees would have been needed to produce a square meter of cityscape. ‘When you look at these cities and see all the lime and lime plaster, you understand why they needed to cut down the trees to keep their society going.’14 The environmental effects are mirrored in the skeletal remains of the people, which show the kinds of malformation found in unequal societies down the ages.

As we go back in history, it becomes clear that the impacts of inequality on the environment and on humans cannot be viewed separately: they are a single system. The condition of one tells us about the condition of the other.

The archeologist Martin Jones represents a growing body of research indicating that human societies started to damage their environments precisely when and where they first started to become unequal, in Bronze Age settlements in the eastern Mediterranean, around 5,000 years ago. These contain typically ‘modern’ contrasts: the treasure-laden burials of tall, straight-limbed elites, alongside the sparser evidence of dwarfish, ill-clad, prematurely aged, malnourished subject classes, and rectangular fields stripped of nutrients by the insatiable demands of the elite for tradable commodity crops.15

Jones also reports that in Britain, excavations of graveyards from Roman times right up to the 20th century have revealed the skeletal malformations typical of a people subsisting on the most basic and monotonous of commodity crops, alongside skeletons with the spinal malformations typical of an elite grown obese on the meat raised and fattened on those commodity crops.16

MALTHUS’S MISTAKE: NOT TOO MANY BABIES, BUT TOO MUCH DEBT

Human and environmental degradation have been and still are widely attributed to population growth, and the introduction of agriculture. The influential science writer Jared Diamond has called agriculture ‘the worst mistake in the history of the human race’.17 The Reverend Thomas Malthus’s persuasive theory of population growth (first published in 1798) seemed to support that view.

According to Malthus, increased food supply leads to overpopulation: the food supply grows arithmetically (from 1 to 2 to 3 tons per acre, and so on), encouraging people to produce more babies. But populations grow exponentially (from 2 people to 4 to 16 and so on). Therefore, he said, humans are doomed to breed up to the limit of their environment’s ‘carrying capacity’ until epidemic, wars or other disasters rectify the situation. The idea seemed obvious, with its simple mathematical formula (and the London slums did rather seem to be ‘teeming’), so Malthus never tested it against real data – which would have shown that people and animals are very good at regulating their own numbers. Later on, people went to extraordinary lengths to find examples of Malthus’s model in action. Disney’s production team tried to find lemmings demonstrating their famous solution to population pressure for the film White Wilderness in 1958, but ended up buying some lemmings, filming them on a rotating snow-covered turntable so that centrifugal force pushed them over the edge, and herding them over a small cliff and into a river for the final shot.18

Further to confound the Malthusian model, Martin Jones’s eastern Mediterranean examples of environmental collapse date from some thousands of years after the appearance of agriculture, and the non-European world is full of examples of agricultures that sustained higher population densities than Europe’s without any negative impact on their environments at all – the reverse, in fact. Outside Europe, highly productive, ecologically stable agriculture has been the norm for thousands of years.19 In many places, peasant agriculture has led to greater biodiversity (Ladakh, which is essentially a high-altitude desert, would have very low biodiversity without its human population, according to Helena Norberg-Hodge20).

Malthus would have been right if he had not focused on fertility but had paid attention instead to the role played by debt, which (as Thomas Piketty has shown) necessarily rises in lockstep with rising inequality. Debt becomes an increasingly attractive investment for the wealthy, and increasingly necessary for the poor: a closed feedback loop that, historically, has only ever been ended by a catastrophic economic or political crisis.21

Unlike population, debt really does increase exponentially. No matter how hard indebted farmers work to increase production, they can only do so incrementally – but their debts mount in exactly the same, multiplicative way Malthus said human numbers did, thanks to compound interest. As soon as farmers, or producers in general, become indebted to banks, simple arithmetic calls the tune and sets the pace, and producers must do whatever it takes to service the debt – or leave the land, as millions did.

The physicist Frederick Soddy explained it like this in 1926:

Debts are subject to the laws of mathematics rather than physics. Unlike wealth which is subject to the laws of thermodynamics, debts do not rot with old age and are not consumed in the process of living… On the contrary, [debts] grow at so much per cent per annum, by the well-known mathematical laws of simple and compound interest… which leads to infinity… a mathematical not a physical quantity.22

And Will Carleton, a poet from rural Michigan, put it this way in the 1890s:

We worked through spring and winter – through summer and through to fall

But the mortgage worked the hardest and the steadiest of us all;

It worked on nights and Sundays – it worked each holiday –

It settled down among us, and it never went away.23

Recently, a number of writers (such as the economist Ann Pettifor24 and the anthropologist David Graeber25) have been pointing out that debt was not originally like this: debt and credit were and are essentially something that communities provided for themselves to buffer the ups and downs of life, support new projects, and keep track of who owed what to whom. It was the monopolizing of money by a merchant elite, the right to create debt, and set its terms, that turned debt into the tyrannical, mathematical and even (in the sense implied above by Frederick Soddy) supernatural force that it became. Production, says Ann Pettifor, ceased to be simply to meet needs and wants, but a race ‘to make food production more profitable than debt’26 with predictable consequences for people, their communities and, ultimately, the land.

This unwinnable contest was a large factor in the agrarian crisis of medieval and early modern Europe, leading to the exodus of the impoverished – first into the cities (a major trend by the 16th century) and then to the Americas and Australasia in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.27 Teresa Hayter writes that:

from the early 19th century to the 1920s, more than 60 million Europeans migrated to America and Australasia, of whom 5.7 million went to Argentina, 5.6 million to Brazil, 6.6 million to Canada, and 36 million to the United States.28

Until 2001, this exodus of the European poor was still the largest mass migration in history.

‘SHEER HUMAN NUMBERS’ RE-EXAMINED

The human story used to be told without its neolithic prelude, so that humanity seemed to emerge from nowhere 5,000 years ago (the dawn of Biblical time), complete with inequality, doomed from the outset to lives of hard labor and counter-productive striving – the Judeo-Christian version of history into which Thomas Malthus’s theory seemed to fit quite easily. Yet Malthus never showed any causal link between ‘sheer human numbers’ and either famine or ecological harm and, when the precise causes of famines, species loss and environmental deterioration finally came to be examined, they failed consistently to implicate population growth. The finger of blame points, instead, at debt, and its essential precondition, inequality.

The Nobel Prize-winning economist Amartya Sen has shown that for every single famine for which records existed, there had in fact been no shortage of food, but a surplus – and a failure to distribute that surplus to the people who needed it. Shop windows might have been full of food, but people simply lacked the money to buy it.29 Often they were priced out of the market by foreign demand, and that was the situation in all of the great famines that marked the onset of globalization in the 1870s, as it had been in Ireland in the 1840s (where pork and wheat continued to be exported, even past the bodies of the starving).30 Sen showed that no such famines had ever been recorded in a functioning democracy – often despite extreme climatic and economic challenges.

Cuba could easily have been the scene of famine after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1989-90 (as North Korea was, after support from China ended at around the same time31). In Cuba, it was egalitarian solidarity that enabled the country to switch rapidly from reliance on sugar exports to a high degree of self-sufficiency. As we saw above, this also coincided with environmental regeneration – as it did under a completely different political regime, after inequality fell in Japan three centuries earlier.

‘Sheer numbers’ were never the issue, but they still have a powerful intuitive appeal – if one believes that a planet is the same kind of thing as a night club. But supposing it were, how many people would fit into it?

In 2008 it was calculated that the world population (then 6.8 billion – but rising to 9 or 10 billion before stabilizing) would fit into a land area the same size as former Yugoslavia, at the same density as Manhattan (in other words, not too dense for comfort, and providing a reasonable amount of open space for recreation). Self-sufficiency would obviously require a lot more space than that – but, not that much more: until the mid-1990s, the Chinese city of Shanghai (like other Chinese cities) was self-sufficient in vegetables and grain. Using the population density of Shanghai for that period (2,588 people per square kilometer) the entire world population could (if it wished!) lead an entirely self-sufficient and self-contained, if vegetarian, existence in a land area slightly smaller than the Democratic Republic of the Congo (2.35 million square kilometers: about a fifth of the world’s cultivated land32), and donate the rest of the planet to wild animals and plants.

This may sound far-fetched, but it is consistent with other studies. For example, a major recent study by Norway’s Development Fund (Utviklingsfondet), gathered data from all available sources and found that 25 per cent of the world’s food was already being produced within cities before the 2007/8 food-price crisis; and presumably much more than that subsequently.33 Cities cover less than three per cent of the world’s land, excluding Antarctica.

The Norwegian report also shows that modern, intensive agriculture produces far less of the world’s food than we think it does – barely 30 per cent, much of which is for animal feed – yet is responsible for 14 per cent of greenhouse-gas emissions (mainly through damage to soils). Fully 50 per cent of world food (including most of the rice we eat in rich countries) comes from peasant agriculture – which has never enjoyed anything like the investment showered on industrial agriculture, and has proved capable of doubling, tripling and even quintupling its yields by organic methods, given modest support.34

EHRLICH’S LAST GASP: TECHNOLOGY AND ‘EYE-PAT’

In the 1970s, Paul Ehrlich and colleagues offered what many still find a compelling explanation for why, despite all the evidence above, human numbers were destroying the earth: technology. Their argument came packaged in a scientific-looking equation, I=PAT (pronounced ‘eye-pat’; environmental Impact equals Population times Affluence times Technology). As societies get wealthier, said Ehrlich, they need more cars, washing machines and air conditioners, which means more roads, more raw materials extraction, more fuel consumed, and so on. All of this means that, for the sake of the planet, ‘they’ cannot aspire to ‘our’ levels of affluence and technology – unless ‘they’ reduce their populations drastically.

This may sound hypocritical, but it touches on uncomfortably pervasive, unconscious assumptions many of us have. For example, in Radu Mihaileanu’s film La Source des Femmes (2011, released in English as The Source) the women of a Moroccan village launch a campaign to have the water from their mountain spring piped into the village, saving them hours of carrying heavy loads of water every day. The petty official handling the decision says: ‘If we give them their pipeline, the next thing we know, they’ll be wanting washing machines and showers’. One flinches slightly at this: most of us use washing machines and showers, know what their environmental cost is, feel guilty about it perhaps… and might like these attractive North African folk to go on living in their beautiful mountain village, untainted by the world of washing machines. An unsettling scenario is evoked, in which villagers and especially the young have to migrate to the city to find work to earn money to supply the new luxuries, the beautiful mountain village becomes depopulated, and its people end up in a grey, dusty, sprawling suburb somewhere… and we feel particularly uncomfortable that this smug, sexist bureaucrat expresses attitudes that we hide even from ourselves.

This vision of inexorable degradation derives from the apparently linear nature of progress: we got where we are along a particular path, and we assume that that is the route everyone will have to take. The engineering scientist Howard Rosenbrock argued against that kind of fatalism.35 He called it ‘the Lushai Hills effect’ after the hills in north-east India, which rise from a maze of wooded valleys and ravines. He took a walk there one morning and somehow reached a summit. Looking down, it seemed extraordinary that he had struck on the one possible route to the top. But of course, he hadn’t – there were plenty of ways of getting there, all different; and indeed other summits he could have reached.36

Most of us have very little say in the decisions that shaped our ‘possibility landscapes’, yet we must live in them and choose from among whatever options they offer. The greatest fuss is made about the smallest choices (whether to buy Indesit or Electrolux, this phone tariff or that, from this provider or the other), which encourages an illusion of free choice like the one created by close-up magicians, when they ask you to ‘pick a card’. More radical choices are either hidden by the sales patter, or under lock and key. Yet they exist.

THE POWER TO CHOOSE A LOW-IMPACT LIFE

I=PAT is promoted as if it were an iron law, decreeing that every improvement must carry an environmental price. But technology is by definition the more and more parsimonious use of natural phenomena: doing more with less. Technological choices should radically reduce impacts – and sometimes they do. I=PAT fails to explain the great differences in impact between countries, shown earlier. Many people in European and Nordic countries, and Japan, enjoy lives just as comfortable as those in the US, but with far lower impact. Even within high-impact countries it is possible to find people who enjoy very high levels of comfort, amenity and health, at very little environmental cost.

In 2012 The Guardian interviewed a couple in Lancashire, UK, who have a modest income (only one of them has a paid job, halving their impact at a stroke) but ‘feel rich because the quality of life is so rich’. They live in a co-housing project (a co-operatively owned development with shared facilities): ‘It’s 41 eco houses and we share 11 cars. We cook and shop communally. Because we’re sharing everything, we’ll have 3 lawnmowers and 6 electric drills instead of 41. We’ve got shared laundry facilities.’37

This very modest, quite unrevolutionary setup is a choice millions of people in Britain would love to be able to have, according to the UK Cohousing network,38 but only a few hundred can exercise it because the housing industry and regulatory system are not set up to favor small, co-operative ventures. If washing machines have become engines of destruction, it could have more to do with the way housing has been atomized, the machines have been commodified, and daily life restructured to maximize profit by turning communal tasks into private ones – so that people who want clean clothes must buy their own laundries.

Even greater economy and luxury are possible with a bit of political initiative. In nearby Oldham, Lancashire, a small number of families have moved into ultra-low energy ‘Passivhaus’ housing where they can walk around in t-shirts in the depths of winter yet pay only £20 ($32) a year for heating – compared to the £550 ($880) for gas alone, just for the three summer months, paid by a neighbor in one of the pre-cast concrete council homes they used to live in.39 These homes only cost an extra £20,000 ($32,000) to build, but Britain only has 150 of them, there is little market incentive to build more, and only market solutions are permitted in the country since public provision of housing was effectively ended in the 1980s. Instead, market incentives favor burning as much fuel as possible: the fuel and power utilities were all privatized and became stock-market listed companies at the same time.

Consequently, most people must live in isolated, expensive, high-impact housing because that’s what’s available – Britain’s rising power inequalities have distorted the ‘possibility landscape’ in a way that favors the needs of a few extremely wealthy landowners, construction firms and energy companies over those of everyone else.

The difference between paying £20 a year and more than £2,000 a year, just to keep warm (and the even greater subjective difference between struggling to keep warm and living comfortably and worry-free, in a t-shirt in the depths of a Lancashire winter) shows what a lot of ‘give’ there is in the I=PAT equation.

We are encouraged to think that reducing impacts is very difficult, and this mindset provides cover for some of the biggest environmental impacts of all: those of the mining and extractive industries, and of globalized freight. If mundane examples like the ones above are kept out of the discussion, it is perfectly possible to be fooled by talk of squeezed profit margins, and of how difficult it is for struggling firms to reduce their environmental impacts as they try to meet the world’s ‘need’ for other ‘scarce resources’ – including the metals used in electronics. Here, the iron laws turn out to be very generously padded on the supplier’s side.

Amrit Wilson tells us that, whereas average return on capital in developed countries is about five per cent, ‘in countries like Tanzania, in sectors such as goldmining and oil and gas, even in 1982 it ranged from over 40 per cent to several hundred per cent’; ‘less than 0.001 per cent’ of turnover is paid in tax. As she says:

Today Tanzania’s workforce is being made available to global capital in new ways for some of the worst kinds of exploitation through the establishment of special economic zones (SEZs) and export-processing zones (EPZs). In these zones, which often take over prime agricultural land, wages are low, there are few health and safety regulations, trade unionism and all labor laws are banned, and if experiences in other parts of the world are anything to go by the workers – often predominantly female – face frequent sexual harassment and abuse.40

The global spread of SEZs was led by the growth of the global electronics industry in the 1980s. Shenzhen, home of the giant Foxconn plant mentioned at the beginning of this book, was one of the first; in fact SEZs first appeared in the People’s Republic of China as a key feature of Deng Xiaoping’s reforms in 1978.41 Having created the conditions for a ‘race to the bottom’, the phenomenon was turbocharged by the arrival of Information and Communications Technologies (ICTs), which allowed wholesale offshoring of industries such as the garment industry, the shoe industry and call centers.42 There are now thousands of SEZs around the world. As pressure on raw-material prices has grown, mining has become a ‘natural’ candidate for SEZ treatment. Profits on the scale mentioned by Wilson are common, together with huge environmental and human impacts.43

The environmental costs are deeply ramified, and go hand in hand with the erosion of equality via attacks on workers’ security and conditions. In their 2010 documentary The Forgotten Space, Allan Sekula and Noël Burch show that containerization of sea freight (which began in New York immediately after the Second World War) was more to do with destroying the power of the dockworkers’ and seafarers’ trade unions than with commercial considerations. Containerization removes the need for dock labor apart from a few, isolated individuals operating cranes. It allows firms to exert much tighter control over the ‘value chain’ and even to extend it, exploiting resources and labor much more easily – hence the explosion of ‘offshoring’, and the amount of energy used in transporting goods.

Containerization is also far less efficient in energy terms than conventional cargo-handling. The bulkier, containerized cargoes require larger ships – which use space extremely inefficiently because containers cannot be stowed deep below decks. The bowels of the ship must therefore be filled with either ballast or heavy, low-value cargoes, which travel almost free – explaining the appearance over recent years of millions of tonnes of heavy stone garden ornaments from China and India in European garden centers. All of this has led to a doubling of the amount of goods carried by sea between 1982 and 2007, so that, by the latter year, shipping carried 90 per cent of world trade. Shipping was by then one of the biggest sources of greenhouse gases on the planet, producing twice as much CO2 as did airlines, and is predicted to rise by up to 75 per cent within 15 years.44

The slowdown in international trade since 2007 has somewhat reduced the growth in container traffic, but any reduction is offset by the growth of oil-tanker traffic: the boom in shale-oil production in Canada and the US has forced traditional oil suppliers such as Venezuela and Nigeria to seek markets in Asia. In 2012, each tonne of oil used in the world had travelled nearly 10 per cent further than it had the year before, making a total of 7.8 trillion tonne/miles for the year, and raising interesting or alarming new security issues. Longer voyages mean more danger from pirates, especially in the seas through which these cargoes must pass, hence ‘it is only a matter of time before we see Indian [war]ships in the South Atlantic’.45

The same lobby groups that drove through containerization during the 1960s and 1970s also succeeded in having sea transport excluded from the Kyoto Agreement on climate change – making shipping a neatly self-contained object lesson in the environmental impacts of concentrations of power.

1 For example, Alec Nove, The Economics of Feasible Socialism, Allen and Unwin, 1983, p 157.

2 Brand, Preston & Boardman, Travelling in the right direction: lessening our impact on the environment, Final Research Report to the ESRC 2006: nin.tl/ESRC2006

3 Danny Dorling, personal communication, 28 Sep 2007, citing Worldmapper.org and WWF Living Planet Report data. See also Dorling, Injustice: why social inequality persists, Policy Press, April 2010.

4 WWF Living Planet Report, 2008.

5 Brian Pollitt, ‘Cuba’s health services – crisis, recovery and transformation’, CubaSí (magazine of Cuba Solidarity, UK), Autumn 2004.

6 Patricia Hynes, ‘War and the True Tragedy of the Commons,’ Truthout, 28 July 2011, nin.tl/PHynes2011

7 P Sahlberg, Finnish Lessons, Teachers College Press, 2011. See also: Alan Moore, ‘What Makes the Finnish Education System Work?’ No Straight Lines, nin.tl/MooreFinland Accessed 16 Feb 2014.

8 Melissa Benn, ‘The Question of Private Schools’, 9 June 2012, nin.tl/Benn2012

9 James K Boyce, ‘Is inequality bad for the environment?’ Equity and the Environment, 15, 2007, pp 267-288, citing Princen, ‘The Shading and Distancing of Commerce’, MIT 1997.

10 Ibid.

11 International Panel on Climate Change; for example see graph at: nin.tl/IPCCemissionsgraph Naomi Klein writes that global emissions rose, on average, 1 per cent per year throughout the 1990s, and ‘by the 2000s, with “emerging markets” such as China fully integrated into the world economy, emissions had sped up [to] 3.4 per cent a year,.’ This Changes Everything, Simon & Schuster, 2014.

12 Andrew Revkin, Global Warming, understanding the Forecast, Abbeville Press, 1992, p 55.

13 PJ Crutzen & C Schwägerl, Living in the Anthropocene, Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Science, 2011. See also Mike Davis, Living on the Ice Shelf, Tom Dispatch 26 June 2008.

14 ‘Forest Razing by Ancient Maya Worsened Droughts, Says Study’, Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory website, 21 Aug 2012.

15 Martin Jones, Feast: Why Humans Share Food, Oxford University Press, 2007.

16 Ibid.

17 Jared Diamond, ‘The Worst Mistake in the History of the Human Race’, Discover Magazine, May 1987, nin.tl/Diamond1987.

18 Danny Dorling, Population 10 Billion, Constable, 2013, pp 132-133.

19 For example, see FH King, Farmers of Forty Centuries, Mrs FH King, 1911; Wayne Roberts, The No-Nonsense Guide to World Food, New Internationalist, 2008; and Colin Tudge, Feeding People Is Easy, Pari, 2007.

20 Helena Norberg-Hodge, Ancient Futures, Sierra Club Books, 1991.

21 Thomas Piketty, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, Harvard University Press, 2014, pp 396-420.

22 Frederick Soddy, Wealth, Virtual Wealth and Debt, EP Dutton, 1933, quoted by Ann Pettifor, Just Money, Commonwealth Publishing, 2014, p 42, commonwealth-publishing.com/?p=201.

23 Will M Carleton, ‘The Mortgage’, in Ralph Windle, The Poetry of Business Life: An Anthology, Berrett-Koehler Publishers, 1994.

24 Pettifor, op cit.

25 David Graeber, Debt: the first 5,000 years, Melville House, 2012.

26 Pettifor, op cit, p 43 (original emphasis).

27 The phenomenon of land exhaustion in Europe since the 10th century is described and analysed by (eg) Fernand Braudel, Civilization and Capitalism, 1981; Immanuel Wallerstein, The modern world system, 1974; Catharina Lis and Hugo Soly, Poverty and capitalism in pre-industrial Europe, 1979.

28 Teresa Hayter, Open Borders: the case against immigration controls, Pluto, 2001, p 9, citing estimates by Bob Sutcliffe in Nacido en Otra Parte, Bilbao, 1998.

29 Amartya K Sen, Development as Freedom, Oxford University Press, 1999.

30 Mike Davis, Late Victorian Holocausts, Verso, 2001.

31 Starved of Rights: Human Rights and the Food Crisis in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, Amnesty International, 2004.

32 Joel E Cohen’s 1995 estimate of the world’s total cultivated area was 13.6 million km2; see How Many People Can the Earth Support? Norton, 1995.

33 A Viable Food Future, Part 1, Utviklingsfondet (The Development Fund, Norway), Nov 2011, p 47, nin.tl/viablefuture

34 Ibid, p 40.

35 HH Rosenbrock, Machines with a purpose, Oxford University Press, 1990.

36 Conversation with Mike Cooley, 2007.

37 Olivia Gordon, ‘How much is enough?’ The Guardian Weekend, 15 Sep 2012.

38 The UK Cohousing Network website, cohousing.org.uk Accessed 19 May 2013.

39 John Vidal, ‘Actively Cutting Energy Bills in Oldham’, The Guardian, 1 Nov 2013, nin.tl/Vidalpassivhaus

40 Amrit Wilson, The Threat of Liberation, Pluto, 2013, pp 104-105.

41 Hsiao-Hung Pai, Scattered Sand, Verso, 2012, pp 165-166.

42 David Holman, Rosemary Batt & Ursula Holtgrewe, Global Call Center Report, 2007, nin.tl/callcenterreport

43 Dionne Bunsha, ‘India’s Viagra – Special Economic Zones’, New Internationalist, Sep 2007, nin.tl/Bunsha2007; Aradhna Aggarwal, ‘Special Economic Zones’, Economic and Political Weekly 41, no 43/44, 4 Nov 2006, 4533–36.

44 John Vidal, ‘CO2 output from shipping twice as much as airlines’, The Guardian, 3 March 2007.

45 Ajay Makan, ‘Oil tanker trade soars on back of US boom’, Financial Times, 15 May 2013.