If you’ve got a talent, protect it.

—JIM CARREY

Most self-help and get-success books orient themselves by placing the reader (i.e., “the talent”) at the center of the discussion: their skills, history, personality. “It’ll all come to you, if only you prime yourself properly for the right breaks.” Fair enough.

But we see things differently.

We know that for 10x talent to thrive in this new unwieldy environment, they are going to need the guidance of someone else: a seasoned, reflective, intermediary force with a separate POV and what we call “skin in the game.”

When we say “skin in the game,” we aren’t just talking about a percentage of earnings.

Skin in the game means way more than financial stakes.

It means emotional and even spiritual stakes.

It means belief.

Strong management that has a vested interest in your success must always be dedicated to your cause, beyond percentages and hyperbole. Your win is their win, and vice versa, at the deepest life levels.

To reiterate, we use the phrase “management” in this book to denote any number of relationships—the word could signify a manager in your organization on whose team you work; it could mean an outside entity with skin in the game who is helping you navigate your career; it could be a leader in your industry with whom you have struck up a mentor/mentee relationship. Whatever the set-up, skin in the game is mandatory. They have to know that your success is their success, too.

In fact, as far as we’re concerned, for any form of management to even be strong, it has to be willing to go to the mat and kill (or die trying) for their talent. The half-invested aren’t worth your precious time.

This skin in the game is an important asset for talent at every stage of their career, because strong management is the only force that can bring the benefits of experience to bear on your maiden voyages. In other words, what a talent is going through for the first time is often something that strong management has dealt with and refined their approach to, situation after situation, year after year.

Even more important, strong management with skin in the game is frequently the only outside entity that can deliver unbiased (or, at the very least, less biased) advice toward aligned interests. If there is one thing the great managers have in common, it’s their embrace of the unvarnished truth.

This is why, for fledgling and experienced talent alike, it takes guts to be managed. You’ve got to be ready to take advice that is sometimes counterintuitive, sometimes hard to hear. Inevitably, managerial advice is most valuable when it’s hardest to hear.

Letting another person help guide your destiny is nothing less than an act of faith.

Skin in the game is what delivers that faith.

WHAT TO DO WHEN YOUR BOSS IS THE BOSS

In order to illustrate skin in the game, we went straight to the top. Nowhere is the utility of this force more evident than in the decades-long, multitiered relationship between supermanager Jon Landau and his most famous client, Bruce Springsteen.

If there were ever two guys who might be described as game changers, Landau and Springsteen are them.

In ’74, Springsteen was just an up-and-coming artist with a few noteworthy records and no hits to his name. Landau, a respected, pioneering rock critic, had the audacity to write, “I saw rock and roll future and its name is Bruce Springsteen.” This bold statement was the first of its kind and was Jon’s first example of putting skin in Springsteen’s game. He literally would be wrong if Springsteen failed, and therefore it was now in Jon’s interest to see the opposite occur.

Springsteen was flattered, of course, and the two struck up a friendship. In those embryonic days of the rock press, the division between artist and critic was not so very wide, and camaraderie of this kind was not completely unusual. What was unusual, however, was just how much they hit it off.

Within months, Landau switched gears and became Springsteen’s producer on nothing less than his breakout album, Born to Run, considered to be one of the greatest rock LPs of all time. (Unless you’ve been living on the moon since August 1975, you probably already knew that.) When Springsteen had a falling out with his then-manager, he and Landau decided to work together as artist and manager, and the rest is rock-and-roll history. For almost half a century, they’ve been thick as thieves, demonstrating the highest level of shared skin in the game—artistic, financial, emotional, and spiritual alignment.

How did it happen?

“When it comes to artists,” Landau told us, “if you love what they’re doing, they can feel it. And that’s a good starting place.”

Unsurprisingly, Jon Landau is a larger-than-life personality himself, with enough great anecdotes and tales for ten books. Still, looking back on those early days, he’s both candid and discerning, and even a little awestruck himself.

“The way I describe it is, we were sort of dancing around each other. I’d written about him, and that was an important review for him, of course, but we had no formal relationship whatsoever.

“So one day he calls me and he says, ‘Jon, why don’t you come down to Long Branch tonight’ over in New Jersey where he was living. He says, ‘Let’s hang out and listen to music, I got some records here, and let’s just keep talking.’ And I say, ‘Sounds like fun.’ But lo and behold, there was a huge snowstorm that night, and I mean huge. Roads are blocked, it’s a mess. So I call him back with the assumption that, you know, we’ll postpone.

“But Bruce wasn’t really a realistic-type person. He wasn’t interested in the weather. He was interested in doing what he wanted to do. And what he wanted was to stick to our plan. I was about to explain that the roads were closed and so forth, but I could tell . . . he really wanted me to visit. So, I said, ‘Bruce, I’ll be there.’ I had no idea how I’d get there.

“It turned out that some trains were running, but completely off schedule. I seem to remember getting a ticket and leaving at around 6:00 p.m. and arriving somewhere around midnight. A six-hour train ride to Long Branch! Bruce’s place was right near the train station. I don’t remember if I just walked there in the blizzard or what.

“We spent all night talking, until 8:00 or 9:00 in the morning. I said, ‘Bruce, I gotta go home. This has been great but. . .I gotta get some sleep.’ Well, he checked and the roads had cleared, so he showed me the best way home on the bus.”

At this point in telling us the story, Landau pauses. He seems to be shuffling through a thick deck of vague memories and lost notions, detours and paths not taken.

“Now, you know,” he says, “I don’t know if that’s why I became the producer of Born to Run and Bruce’s manager. But I have the feeling—I have always had this feeling—that if I hadn’t gone there that night . . . it wouldn’t have happened.”

What we glean from this awesome story is a lesson for every aspiring talent and every manager out there: Going out on a limb and demonstrating real skin in the game, especially without an agenda, is the truest—no, the only—way to build a credible talent-management bond.

Landau is quick to point out that he and Bruce don’t usually deal in role titles like “manager” or “producer.” But when the Boss lost his manager and was unsatisfied with working through entertainment lawyers, he knew he needed someone with skin in the game to represent him.

As Landau explains: “Record companies don’t want to deal with an artist that wants to manage himself. If the artist starts calling up direct, asking, ‘Why am I not making the Billboard charts?’ it’s very uncomfortable. You have to have kid gloves on when you’re talking to the talent, and it’s stifling.

“From the other side, the artist also can’t say ‘Screw you’ to the record company and get into a big fight about some important things the way a manager can.”

A rapidly rising star with a full-throttle work ethic and a schedule to match, Bruce turned to the person he related to best—Landau.

“We had a six-month trial period. I told Bruce right off that I had no business background at all. I didn’t know anything about it. He said: ‘You’re a smart guy. This other stuff, I get the feeling it’s not rocket science. And we trust each other, that’s the important part.’”

Landau jumped into the deep end, handling all aspects of Bruce’s career and enlisting the best in the biz to educate him wherever he needed guidance.

For contracts, he called on David Geffen. “I learned so much about management from David,” Landau says. “The way he would agitate for artists he believed in. The way he wouldn’t take no for an answer. The way he would never quit. Also, he had this belief in quality, especially about people. Everybody associated with him was the best at what they did.”

Over time, guys like Geffen and Landau helped reshape the spirit of rock-and-roll management—from cigar-chomping loudmouths exploiting and sometimes even bullying their own people to serious representatives who respect their artists and defend their talent to the world. Landau told us that in forty-five years, he and Springsteen have raised voices to each other maybe three times. Yet an ongoing dialogue and very open communication is the key to their bond.

“In the early years,” Landau explains, “we were looking to be perfect, and one of us would get onto an idea that the other didn’t see, and we didn’t know how to close it. But since we’ve gotten older, we’ve learned how to bounce ideas and let go. You have to learn where to stop. You have to learn to grow up.”

What’s also striking is that, forty-five years down the line, Landau still takes enormous pride in what he contributes to Bruce’s career in the present.

“The show went on at 8:00,” he says, recounting a concert challenge. “I watched the first hour, a big outdoor show. Then we went down to catering, which was near enough to the stage that we could hear the show. I’m standing there with George Travis, Bruce’s long-time tour director for almost as long as I’ve been with him, and Barbara Carr, the partner in my management company. All of a sudden, the sound cuts out. I say, ‘George, what’s happening?!’ Well, as you can imagine, we went flying out of our seats.

“It turns out that the primary generator had gone south. It was like the show stopped dead. Oh my God, never had anything like that happened. We had a safety generator, and we scrambled to hook it up. Finally, we get things humming, and Bruce works twice as hard. The crowd got as good a show as he could do that night.

“Show’s over, Bruce is walking down a ramp, and I’m standing on the ramp, and George is with me. And to our amazement, Bruce is . . . ecstatic. Because the show has ended on a high. He looks at us, and he says, ‘Gentlemen, there’s only one thing I want to hear.’ Well, George, God bless him, starts explaining in detail what happened with the generators. I grabbed his arm and said, ‘George, I’ll take it from here.’ Bruce wasn’t interested in the details. I knew what he wanted to know right then and there, so I looked Bruce in the eye. ‘Bruce, that will never happen again.’ Of course, Bruce, George, and I knew that no one could literally promise it would never happen again. . .but that was the closure that was needed right at that moment.”

The reason Bruce Springsteen could take Landau at his word is because of half a century of skin in the game.

The energy you create around you is perhaps going to be the most important attribute. In the long run, EQ trumps IQ. Without being a source of energy for others, very little can be accomplished.

—SATYA NADELLA

WHAT’S REALLY AT STAKE

Sometimes skin in the game doesn’t come from a single individual. Just as Springsteen went out on a limb when he saw 10x qualities in Jon Landau, Landau himself knew he had met his 10x business partner for life when he connected with Barbara Carr, a legend in the world of rock music. “Couldn’t get along without you, Barb,” is the way the Boss put it to the crowd on the night he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

Barbara Carr knows a thing or two about talent and management.

A student of Marymount College and the London School of Economics and a former publicist at Atlantic Records, Carr has a reputation for being capital-T Tough, a formidable gatekeeper who is incredibly organized and smart and suffers no fools. Before joining the Springsteen camp, she was already widely credited with having created tour publicity, whereby music artists interface with local media as they make their way around the globe. A simple and logical concept, but like many great ideas, no one before Barbara had the Future Vision to see it. She literally changed the game.

Today, Carr herself travels with Springsteen on most dates of every tour. She also leads his considerable charity efforts and is a trustee of The Kristen Ann Carr Fund for sarcoma research, named for her daughter who died from the disease in 1993 at age twenty-one. As of this writing, The Kristen Ann Carr Fund has raised more than $23 million since its inception in 1993.

And to what does Barbara Carr attribute the incredible success and remarkable longevity of her team?

“We manage each other,” she says, with an infectious laugh. “We’re very respectful, very careful with each other, because everyone has their ups and downs, their good days and their bad. It’s like family. It’s about staying calm, having some humility and some perspective and also just really keeping in mind that everybody involved is a human.”

The record biz was very much a boys’ club when Carr got started, and she can still recall earning $5 an hour at Atlantic in the 1970s—any number of small-minded guys wanted to take her job or see her fail. As the first woman to become head of a department at a major record company, she cracked the glass ceiling for several generations that followed, and stood her ground with some of the most feared characters in show biz. Today a powerhouse manager in her own right, Carr forms an interesting equation when describing the formidable managers and execs she’s worked for and worked with over the years, from Landau to the infamous Atlantic Records founder Ahmet Ertegun to the legendary former Sony Music Entertainment boss Tommy Mottola and beyond.

“The reason these people are known for having a large leadership aspect, the reason they can wield power so well . . . is because of their passion. Yes, they are managers, but they’re really artists themselves, they have an artistic part of them that is undeniable. Look at Ahmet. The story goes that he got started selling records out of the back of his car. He’s an artist, in that he’s a visionary. Jann Wenner had a vision when he started Rolling Stone. Jon Landau certainly always had a vision for Bruce, though perhaps he wouldn’t put it that way. But these guys were visionary and artistic themselves, and that’s why they could lead artists.”

This, for our money, is one of the best descriptions of the yin-yang nature of talent and management. Great managers have skin in the game because management itself is their art, their talent.

Their own vision is part of what’s at stake.

Smart 10x talent can spot that key difference a mile away.

For Carr, this vision must combine with a genuine emotional attachment to the talent’s work for management to be truly effective. At a recent screening of Springsteen’s new documentary, Western Stars, she burst into tears.

“I was crying so much at the end that I could barely tell Bruce what I thought of the movie. I just got moved, totally. You know, all of us are getting older, Bruce just turned seventy, and the movie makes you think: I am going to stop and smell the roses, I am not going to sweat the small stuff and care who left their shoes in the middle of the kitchen or whatever. You know—I am capable of change.”

She pauses to reflect, and adds, “How can I ever retire? Why would I retire from this deep emotional experience? I’m so proud to take this to the rest of the world.”

Recounting all this to us, Carr cried a little again and tried to apologize, but we understood where she was coming from. She has the deep sense of connection great management always has to the talent and their work. That heart-and-soul connection is what’s at stake when we say skin in the game.

After a sigh, Carr captured the nuance of this talent-management yin-yang even more succinctly. “It’s like . . . we’re managing Bruce . . . but there’s a way that you might even say he’s managing us right back . . . through his inspiration.”

One of my greatest talents is recognizing talent in others and giving them the forum to shine.

—TORY BURCH

DISTORTION, REVERB, AND TONE

Skin in the game isn’t just the glue that holds rock stars and their superstar managers together. It’s a state of affairs without which no business can function. Wherever you work, in order to be 10x, you need your boss or manager or team leader to understand that you’re hitched together, that you share fates.

As we’ve noted, this means keeping an open mind even when the guidance isn’t attractive at first glance. After all, what talent in their right mind would listen to someone advising them to turn down millions of dollars for a few months of easy work, in order to go lose money on something more difficult that might pay long-term dividends? Smart talent would, if they knew their advisor had real skin in the game. As you learned in Chapter 3, John Mayer did—because that’s what smart talent does.

In fact, convincing talent to make counterintuitive career moves is a major part of our job, and it’s only possible once they know that we sink or swim together.

Our tech clients, for instance, often look to us to advise on which engagement is right for them when they have to choose between two, three, or even four active offers. In one such instance, a coder named Aviva was looking at two opportunities that both had appeal, but one was offering a much better rate. Despite our own desire to make the bigger commission, we advised Aviva against taking the higher paying gig because the founder doing the hiring seemed like an egomaniac and our Spidey senses were on high alert.

Aviva resisted our advice at first—she really liked the idea of the better rate, not just for the money but because it would have been the most she had ever made, a symbolic win.

She said, “Are you guys sure you aren’t leading me away from my big break?”

We had to remind Aviva that our advice was not mere opposition—we would be making less money, too. We said, “The only possible reason we would guide you like this is for better long-term benefits . . . for you and for us.”

She got it: Our wagons were hitched.

We recently looked into the company that had offered Aviva a higher offer, and it is no more. We certainly don’t get it right every time, but this was a corner so easy to see around, it was practically transparent.

As we said, it takes guts to be managed, and not everybody has the stomach to embrace it with the same gusto. It’s a practice, and a practice takes practice.

Gary was co-founder of one of the top ten websites in the world when he came to us seeking management. We were happy to take him on as a client, but we soon learned that Gary could be paranoid in unpredictable ways. Right out of the gate, every piece of advice seemed to put him on the defensive, and even after we secured him his first two stellar engagements, he was ready to walk because it took us a bit too long to find those first gigs for him. Despite our business model really aligning with our client’s interests (we earn a percentage of the client’s revenue), he still was sure there was some angle. It was only through careful explanation that there was no way we could win without him winning that we got things back on track. Of course, this was a sign of trouble to come, but he was quite exceptional and worth the time and attention. More than once, we had to talk him off the ledge. Despite the fact that he was making more than he had before and getting more praise than he had before, he tended to equate input with hostility. It was chronic.

One of Gary’s customers was paying him quite well, but would make requests that really pushed his buttons, and after a couple behind-the-scenes meltdowns, we knew we needed to intervene. We came up with a plan. We taught Gary to come to us first when something got him riled up.

We convinced him to:

1. Vent to us.

2. Take time to adjust to the new information.

3. See things from the other side.

4. Let us play bad cop when needed.

One of the methods we have employed to help Gary sounds comical but it’s darn effective: Whenever Gary gets particularly sore about an email he’s received, we have him read it out loud, with several different vocal intonations. Read it once as though it was angry. Now read it as though it was super matter of fact. By doing this he is able to see how he inserts his own feelings and ideas on to words that may or may not have included those feelings. This simple ritual has made it very clear to him that he is not always right about what he thinks he hears, or, to put it more accurately, he is always interpreting matters in a subjective way—it’s in the nature of being human. Getting in touch with his own subjectivity has allowed Gary to make small perceptual shifts, in order to interpret (in fact, reinterpret) input differently (i.e., maybe they are not angry). Overall, we have found this to be a great technique in helping our clients and team parse what is there from what they think is there.

None of the above would have worked had Gary not developed a sense of our skin in the game first. The most important thing we taught him along the way is that there is really no way for us to exploit or take advantage of him without shooting ourselves in the foot.

MOMAGERS, SPOUSAGERS, FRIENDAGERS, AND OTHERS

Who has skin in the game in your life?

In the entertainment world, it’s not uncommon to have a family member, spouse, or friend in one’s corner, especially in the early days of one’s career. In the professional world, it’s equally prevalent to find a mentor or coach through existing connections—someone who can help guide at the personal level.

Because of the premium placed on trust and familiarity when skin in the game is at play in a manager-client setting, it makes a certain amount of sense to seek advice and guidance from those closest to you. Having a momager (a mom who is acting as your manager) has many benefits. After all, who wants to see you succeed more than your own mother? Spousagers and friendagers can sometimes get in on the act, too. What good friend wouldn’t want to help you when asked? In some cases you may not have another option, so asking those closest to you for advice and guidance may seem like a better option than going it alone.

Still, there are a few obvious pitfalls to be aware of when enlisting the near and dear. For starters, every industry has its standards and practices. If your momager isn’t familiar with industry norms, she may suggest things that are way out of step. We always joke that if you showed a non-entertainment attorney the best record deal that has ever been done with a record company, they would advise their client not to sign it because the terms are so bad. Furthermore, simply wanting the best for someone isn’t exactly a credential, so the Third Party Effect, which we’ll talk about in Chapter 7, is weakened.

We heard a story, hopefully an urban legend, about a Millennial writer who misspelled a word and, when her editor corrected it, she told her editor that that’s how she spelled the word. When the editor insisted that the word be fixed, the writer called her momager from the office to scold the editor.

In a hilarious Fox News piece titled “Entertainment pros: Most Hollywood moms should be moms, not momagers,”1 writer Hollie McKay points out the inherent conflict of interest in momagering. “Wanting what’s best for your kid, but also wanting what pays the most for you—that makes being a momager way too risky a proposition.” Cautionary tales include Brooke Shields’s mom, Teri, urging her minor daughter to appear nude in a role as a child prostitute, and R&B crooner Usher being forced to fire his momager, Jonetta Patton, for “different view and mind-set.” Ariel Winter, of television’s Modern Family, fired her momager and replaced her with her sister. We hope that works out better for her, but can’t help noting that it couldn’t have been very fun firing your own mom.

Paula Dorn, co-founder of the BizParentz Foundation, a nonprofit corporation providing education, advocacy, and charitable support to parents and children engaged in the entertainment industry, paints a grimmer picture. “It seems as though many inexperienced parents believe they should be taking on career-enhancing tasks for their child without understanding what is appropriate.”

Familial and friendship support should always be used with discretion.

Still, it’s understandable that people gravitate toward working with those they can relate to, those who have “automatic” skin in the game, because you will be close to your manager if the relationship’s any good. Even if you can keep your family and friends out of your business, it is our belief that, in today’s career-heavy world, the talent-management or manager-client relationship is one of the most important in a person’s life, and it can stand alongside relationships with parents, children, siblings, spouses, and truly close friends to vie for your daily focus and attention. Like those other relationships, the manager-talent connection requires trust, demands patience, and induces growth. Coasting simply won’t do.

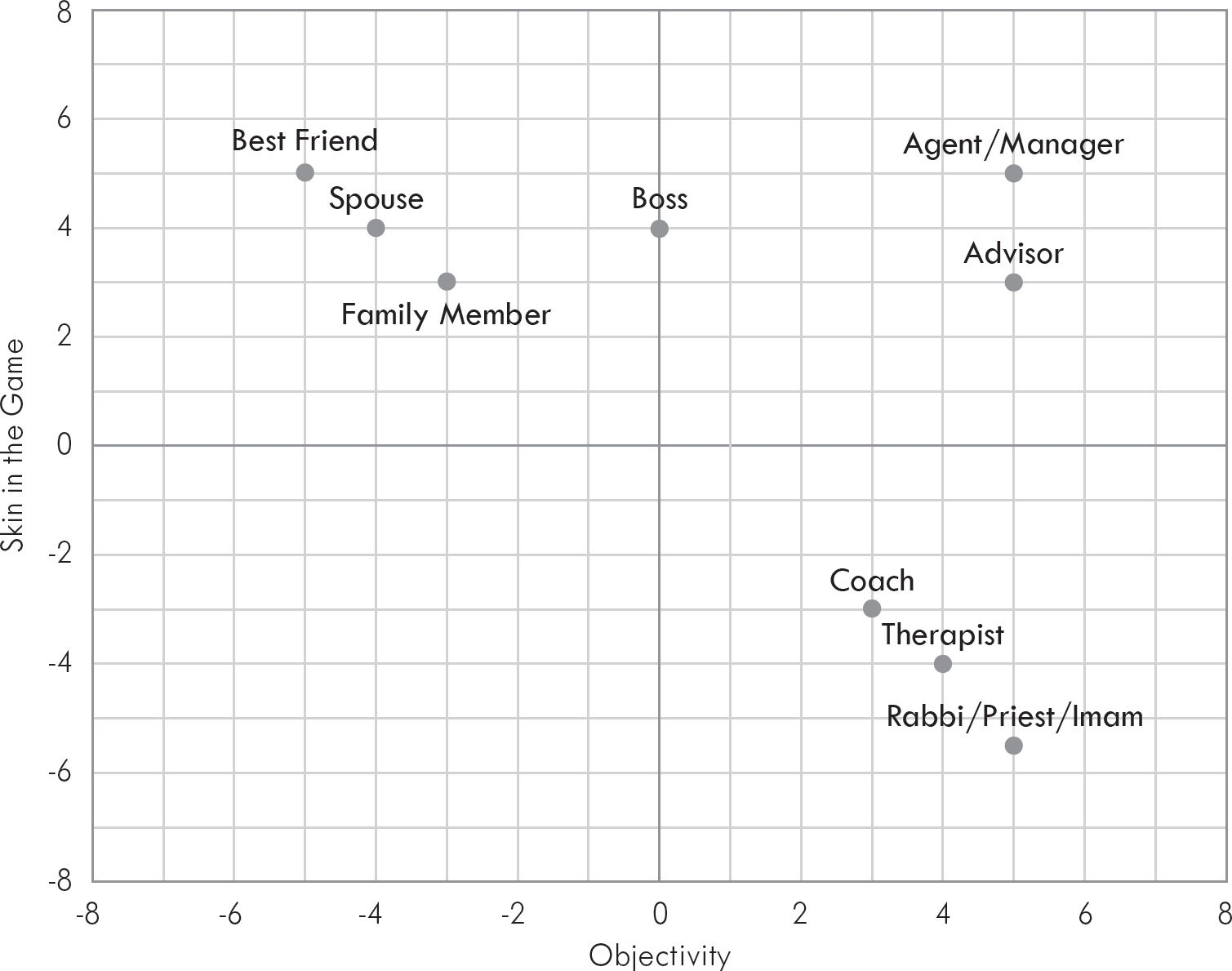

Not all “local” or “automatic” managers are created equal. Michael has created this hair-raising chart (see below),2 which indicates the basic tenets of Objectivity versus Skin in the Game as demonstrated in relationships with Rabbi/Priest/Imam, Therapist, Coach, Boss, Agent/Manager, Family Member, Spouse, and Best Friend.

Obviously, the positions are “ballpark” but the takeaways embedded here are not to be ignored:

• A boss—a good boss, that is—will likely have the greatest balance of skin in the game and objectivity, but they don’t have an excess of either. They want what’s best for you, and your destiny affects them, but not the way it affects your family. (In Chapter 8, we’ll talk about how you can cultivate skin in the game from those who manage you.)

• Your best bud, your uncle, and your spouse have a lot more skin in the game than they do objectivity. What happens to you will likely affect them fairly directly; so much so, in fact, that they probably can’t do the proper distancing necessary for the strongest advice.

• Your coach, therapist, or religious guide bring greater objectivity, but at the end of the day, their investment is not as life-or-death as family members and spouses.

• Only the agent/manager can provide high levels of skin in the game matched by full-force objectivity. It’s their raison d’être, the nature of their occupation.

Sometimes you may need to mix and match to get all the best elements for strong management from more than one source. Once skin in the game is firmly in place, strong management can deliver an invaluable dimension to the talent it represents, what we call the Third Party Effect. We’ll go there next.

SKIN IN THE GAME FOR MANAGERS |

|

0x Management |

Doesn’t have any focus or understanding why alignment is important. Charges should do what they are asked because it is their job. |

5x Management |

Knows that having skin in the game with the team is a very important element of trust, but is not clear how to create it and communicate it. |

10x Management |

Helps to create a cohesive team and can articulate how everyone’s success is tied to one another, knowing and demonstrating that their recommendations are beneficial to each team member, because their destinies are connected. |

SKIN IN THE GAME FOR TALENT |

|

0x Talent |

Doesn’t really understand that giving people a vested interest in their life/career has concrete value. Believes people should help out of the goodness of their hearts. |

5x Talent |

Knows that having partners with skin in the game can be a huge boon to their goals, but has yet to identify who can play that role, and doesn’t know how to secure the right person. |

10x Talent |

Creates a team filled with alignment where wins are shared with those around them and vice versa. |

TAKEAWAYS FROM CHAPTER 6

• Skin in the game is our catchall phrase for the high level of investment every strong manager needs in their talent, and talent needs in their manager.

• Strong managers are after much more than a percentage. They have an emotional and spiritual stake in the talent’s future. They believe.

• Really and truly loving what a talent does is the healthiest starting place for management. Deep respect and trust are the best starting place for the talent.

• Skin in the game is the most honest, most logical way to build trust with a prospective talent. Once the talent knows your wagons are hitched, trust follows.

• Smart talent will listen to a manager’s sometimes difficult advice, as long as the talent knows that manager has skin in the game.

• It takes a visionary, empathetic sensibility to lead great talent.

• Ultimately, the management-talent connection is symbiotic: the two entities succeed or fail together.