“A total eclipse,” Sutton said.

Sophie, when she got home from wherever, said, “What a marvellous eclipse! Everyone’s out watching it.”

Nieve knew better. It was not an eclipse, or not what normally constituted one. For one thing, it lasted for hours, then never really ended. The sky remained overcast and dark at the edges as though bordered in black. It was unnatural and frightening, although her mother didn’t seem troubled at all, and her father only frowned and shook his head as he stood blank-faced at the window staring out.

That night in bed Nieve kept mulling it over. What had happened was impossible, but it had happened. She’d seen it; she’d seen them. Two more of them. But who were they? Why were they here in her town? What did they want? Too many questions, all barring the way to sleep. Her thick white cotton sheets rustled like sails as she turned on her side, and then as she turned onto her other side, and then when she kicked her feet – she was so restless! – and then when she flipped onto her back. She knew she should get up and make some warm milk, or read the dictionary, or do something . . . when she heard an unfamiliar noise. She lay very still, no more fidgeting and rustling the sheets. She listened intently. It wasn’t a middle-of-the-night house sound, one of those abrupt creaks or cracks she sometimes heard, and it wasn’t a Mr. Mustard Seed sound, the kind he would make if he were to creep up from the basement to check things out. It sounded more like a marble rolling across the hardwood floor. It was faint at first, but as it got closer to her room, it grew louder, and seemed to be rolling faster, gaining momentum. She lay rigid listening to its approach. It can’t be, she thought . . . and then it shot under her door, and across her floor, and before she even had a chance to react, it was on her bed, and on her! She jumped in fright and smacked at it but couldn’t stop it as it rolled up her arm, over her shoulder, her chin, and plunged into her gaping mouth. That blasted candy! She gagged and spat it out and scrambled out of bed, coughing violently.

Still coughing, she bolted over to her closet – the thing was following her! She grabbed the baseball bat that she’d shoved in there after her last game of the summer. Before the jawbreaker could roll onto her foot, she took aim and whacked it hard . . . once . . . twice . . . and the third time she whacked it even harder. It exploded with a BOOM! like a fat firecracker going off. What was left of it sizzled and burned and finally expired in a cloud of fluorescent green smoke, leaving behind nothing but a scorch mark on the floor and a putrid smell in the air.

Nieve stood trembling, staring at the spot where it had been, and expecting her parents to show up any minute, angry, rubbing the sleep out of their eyes, and demanding an explanation for what they might think was a stupid prank.

They didn’t come, which was worse than being unfairly scolded. What if she’d been seriously hurt? Her only consolation was that she didn’t have to try to explain what had happened.

Once her heartbeat had slowed to normal, Nieve leaned the baseball bat up against her nightstand, close by just in case, and opened her window. The stench in her room was unbearable, a rotten swampy sulphuric smell. She climbed back into bed, a little nervous about the window being open, but she couldn’t stand the stink. The cool, fragrant air that wafted in did help dissipate the fumes, although before they were completely gone, and probably because of them, she grew drowsy and soon drifted off. And because she was so soundly asleep, she didn’t hear the silky voice that was also carried into her room, a thin thread of sound woven into the night breeze. Nieve, it said softly. Nieve, Nieve . . . .

The next morning, Sutton asked her if she’d run to the pharmacy to buy some tissues. That very night was to be the sympathy gig for which he and Sophie had been rehearsing so strenuously – he had anyway. He figured that five or six boxes might be needed.

“But Dad,” she said, “don’t you know it’s closed?”

“Not any more, En. New owners. That’s what your mother said.”

“Oh. I wondered about that. And they’re open already?”

“Apparently so.” He pulled his wallet out of his back pocket. “Here’s a ten, that should do the trick.” Normally, he’d also tell her to buy a treat for herself, a chocolate bar or a bag of chips, but this time he didn’t.

Forgot, Nieve sighed, as she started toward the door. She knew there was no point in telling him what had happened last night, but just because her parents had lost interest in her didn’t mean that she felt the same way about them. She turned to look at her father, saying, “What is this job you’re doing, I keep meaning to ask?”

“It’s for Mortimer Twisden.”

“That rich guy from the city?”

Mortimer Twisden, owner of several huge pesticide factories, had recently bought the oldest and most beautiful and most secluded house in town (there was only one, actually) and used it as his weekend place. The house, which had belonged forever to the Manning family, used to be call “Woodlands,” but for some reason no one could figure out, he changed it to “Ferrets.”

“The very same. His wife died unexpectedly, about a week ago. He’s holding a wake for her at his place here and Sophie and I have been hired to provide the . . . you know, the grief. It’s a pretty big deal.”

“I’ll say. He must be really sad.”

Sutton nodded, and said, without much conviction, “Yeah. Inconsolable.”

When she stepped outside into the dim, overcast morning, Nieve tried not to let it get to her, the unnatural light, dusky-dark with a faint yellowish tinge. It seemed to be neither day nor night, but some lost place in between. How long was it going to last? She did have a sense that the sun was trying to break through, which might only be wishful thinking. But then, if the sun weren’t trying there might be no light at all, only deep unrelieved darkness.

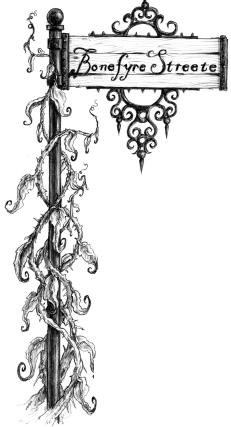

Nieve ran down the lane to town, enjoying the running at least, the thrill of surging free through the morning (no school!), and the familiar feel of her hair whapping against her back. Her enjoyment didn’t last long. She came to an abrupt stop at the foot of Main Street, where someone had erected a new street sign, if you could call a sign new that was so weathered and bent. A prickly, purple-leaved vine twisted around its cast-iron shaft, and the sign affixed to the top of it read, Bonefyre Streete.

What? Main Street wasn’t the most original name around, but it had always been called that. Looked like somebody was trying to turn the place into a tourist town with fake, old-fashioned “streetes” and “shoppes.” Odd that Mayor Mary had allowed it. But then, maybe she didn’t know. The sign can’t have been up for very long, Nieve thought, despite looking as though it had been rooted on the spot for centuries. If so, she’d make sure Mary knew. Once she was finished at Exley’s, she’d find the mayor and tell her.

Arriving at the pharmacy, Nieve saw another new-old sign. This one, a wooden signboard hanging above the door, was carved in the shape of a mortar and pestle. Except that the mortar was a skull with the top sheared off and the pestle a bone sticking out of it. The sign’s white paint was cracked and dirty and the black letters painted on it were faded to grey. Barely legible, Nieve read Wormius & Ashe the names that arched across the skull’s forehead. Below, the word Apothecaries formed a kind of grim smile that served for the skull’s mouth. The sign swung back and forth on its rusted bracket, squeaking and creaking, despite the stillness of the morning. This didn’t appear to disturb the chubby bat that was suspended upside-down from the tip of the pestle, wrapped up in itself like a round brown parcel. Greedy thing must have eaten a bagful of moths last night, Nieve thought. She even thought she could hear it snoring contentedly. But surely not.

She wasn’t at all sure that she wanted to go in. Shielding her eyes, she tried peering through the door, but it was too dark within to make anything out except for some bulky, indefinable shapes. Dad was wrong, she decided, it’s not open . . . that is, she hoped it wasn’t, but when she tried the handle it turned easily and the door gave way.

Nieve stepped cautiously over the threshold and into the store. Despite the weak light coming through the front window, it was very dark inside. No overhead lights were on, and yet as far as she knew there hadn’t been a power outage in town. Towards the far end, where the dispensary was, she did see a small light shining and she headed toward that, navigating between the counters more by touch than sight. Her fingers trailed over bottles and jars, and moving along, she touched something soft and thick that felt horribly like human hair. She pulled back her hand in alarm, but then remembered that Mr. Exley used to sell wigs for people who got sick and lost all their hair, so this was probably one leftover from when he must have so hastily cleaned off the shelves.

Still, she felt uneasy. She told herself to turn around, to leave. It was dumb to be fumbling around in the dark, dangerous even. The new owners couldn’t be wanting business too badly. But she couldn’t stop moving toward that light – it seemed to draw her on. It flickered and wavered, beckoning. Candlelight, she realized, and the closer she came to it the more agitated the candle’s flame grew, as if she were a gust of wind that had stirred up the air in the dusty old store.

As she arrived at the dispensary, a figure rose up suddenly from behind the counter, clearly calculated to startle her. She did give a start, but more so because she recognized him. It was the same tall gangly man she’d seen bicycling into town dragging the darkness with him. He stood directly behind the candle and the light it cast gave his already narrow and ghastly face an even more ghastly aspect.

He smiled down at her with an equally ghastly grin, and said, “May I be of some service, young lady?”

Nieve, determined to keep her cool, said evenly, “Yes, I would like to buy some tissues. Six boxes, please.”

“Tissues?” he said. “Tissues. What an interesting request.”

She didn’t like the way he said “tissues.” And she couldn’t think of anything less interesting.

Nevertheless, he said it again. “Tissues. Hmmm, let me see.” He placed a long, stick- thin finger on his bony chin and tapped it a couple of times. “Mr. Wormius, tell me, would we happen to have any tissue on hand?”

Confused, Nieve looked around to see who he was talking to, and it was only then that she noticed the top of someone’s head – wide and moon-white – behind the counter, barely cresting it.

“Tissue, Mr. Ashe?” The round head now rose above the counter and came into full view. (He’s climbed onto a stool, Nieve thought.) He appeared with a considering expression on his large, smooth, dish-like face. His eyes were as grey as gravel and unadorned with either lashes or eyebrows. “Why, I believe we do, Mr. Ashe,” he said in a raspy voice. “I believe we have several boxes of . . . tissue.”