In her rush to get through the door of the pharmacy, Nieve didn’t observe as closely as she might have done the woman who passed her going in. She did note that the woman radiated a frostiness because she felt it in passing, as if she’d pushed through a cold current. This caused her to glance up briefly, taking in the woman’s pale, perfect features, the elegant, upswept hairdo, the ritzy clothes, the confident stride. Altogether the woman looked as if she knew exactly where she was going, and why. Nieve didn’t try to warn her off.

Instead, she hurried down the street, trying not to think about how those two creeps in the pharmacy had known her name . . . and that wasn’t all they seemed to know about her. As she passed the bookstore, she saw that DunstanWarlock was arranging a new window display. This was something he did so infrequently that there were thick shoals of dust in the window and long-dead flies belly-up on the foxed and yellowed books.

Glancing out at her, the bookseller straightened, tipped his hat, and smirked. He’d never acknowledged Nieve before and she couldn’t see why he did so now. She ignored him and kept on. But her stomach tightened in distress only a few steps ahead when she realized why he’d tipped his hat at her. On his little finger he was wearing a gold ring with a black stone, the very same kind of ring that her mother had been wearing the night of the storm. He had wanted her to see it.

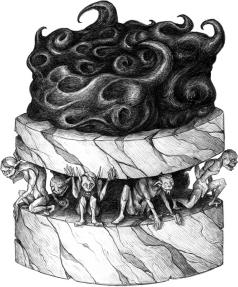

Nieve picked up speed. The street was oddly empty: no one was out shopping or running errands, visiting the library or dropping into the post office for a chat with Mrs. Welty, the postmistress. When she’d passed by Redfern’s Five & Dime, she saw that it was closed now, too. The storefront windows were covered with black paper. Wishart’s Bakery was open, but when she stopped to see what kind of cookies and squares they had on offer, she saw instead a single cake displayed in the window on a peculiar pedestal cake stand. The stand was made of grey marble, stained and chipped. Around its base were detailed carvings of strange men. They were like bald, ugly children, pug-nosed, with crafty eyes, pointy ears, and sharp teeth filling their leering mouths. These carved men were holding up a marble plate upon which sat what Nieve thought must be a chocolate cake, although it was so dark it could have easily been licorice. The cake’s icing had been whipped into fierce peaks as sharp as claws. In colour and consistency the icing reminded her of Genevieve Crawley’s lipstick.

Nieve gazed at the cake, unable somehow not to. She had no desire to sample it. Her stomach tightened even more the longer she looked at it, and yet it was . . . .

“Divine,” someone beside her said.

Nieve had been so absorbed that she hadn’t noticed Alicia Overbury sidle up beside her.

“It’s icky, if you ask me.” Nieve pulled her gaze with difficulty from the window. “Why aren’t you in school?”

“Why aren’t you? ”

“I’m sick.” This wasn’t a lie, she’d witnessed enough this morning to make anyone sick. Although Alicia did look sick. Not only did she appear wan and listless, but she was a mess. Her clothes were rumpled and torn, and her face was dirty, flecks of mud on her cheeks and the corners of her mouth smudged with jam. Not at all her usual prim and prissy self.

“You’re missing out. We play games all the time and get loads of treats.” While Alicia spoke, she continued to stare intently, hungrily at the cake.

“Why aren’t you there then, if it’s so much fun?”

“Night school,” she said tonelessly. “We’re starting night school.”

“Night school?”

Alicia nodded and licked her lips, her full attention devoted to the grim pastry in the bakery window. That’s when Nieve saw that her tongue was black. It wasn’t simply stained from eating black candy, but had turned black. She tried not to stare, but it was so freakish and ugly. Not that Alicia noticed.

“I don’t want to go to school at night,” Nieve said quietly. Amazing, but she was beginning to feel sorry for Alicia. “Going during the day is bad enough. Why do you?”

“No choice. You’ll have to go, too. The truant officer will come and get you. He’s horrible. I’ve seen him. He’ll come at night and drag you out of your bed.”

“I’d like to see him try,” Nieve said stoutly.

“Don’t worry, you will.” Alicia finally turned to look at her.

Nieve saw then how zoned-out she was, her eyes drained of their usual spark and glint. This wasn’t the exasperating Alicia she knew. Exasperating, but still lively and full of herself and with-it. Those treats aren’t jawbreakers, Nieve thought, they’re mindbreakers.

“Alicia, listen, don’t eat any more of those candies or anything else like them. They’re really not good for you. They’re harming you.”

“That’s a laugh,” Alicia said, not laughing at all, but turning once again toward the window to stare and stare at the black cake.

Nieve knew she had even more reason now to see Mayor Mary. She backed away from Alicia and ran headlong to the clinic, troubled, but not without hope that Mary would understand what was happening and know how to stop it. When she arrived, however, and pushed eagerly through the door, she found the clinic abandoned. No one was minding the front desk and no one was seated on the chairs lined up against the wall reading tattered old magazines and waiting their turn for whatever medical advice the mayor had to offer.

Unsure of what to do next, Nieve walked over to the receptionist’s desk. She’d noticed that a pile of papers had fallen onto the floor beside it, along with a couple of pens and a tongue depressor. A coffee mug with a jokey I’d Rather Be Dancing inscription lay toppled over on the desk, as if the mug itself had given dancing a shot and it hadn’t worked out. Drips of coffee were splattered on the pages of the appointment book and a large, sloppy stain had spread over the ink blotter. She touched it – still damp. Several empty medicine bottles sat on the blotter, lids tossed aside. She picked one up and read the label: SCATTERBRAIN’S SUPER-DUPER EXTRA-STRENGTH HEADACHE PILLS. Mary must have come down with a terrible headache, Nieve concluded. No surprise there. The headache must have been so sudden and sharp that she’d knocked over her coffee and the papers and . . . and . . . had gone home.

At a loss, Nieve supposed she’d have to go home, too. Spotting a box of tissues on the filing cabinet next to the desk, she wondered if it would be okay to take it if she left a note promising to replace it later. Hesitating – it didn’t seem right – she heard a faint muffled sound coming from somewhere in the back. She crept over to the door of the consulting room and put her ear against it. Nothing. As quietly as possible, she turned the knob and opened the door a crack. She peeked in, but saw no one. Nor was there anywhere for a person to hide – or be stashed – since the room contained only a couple of chairs, an examining table, Dr. Morys’ desk, a small cabinet, a garbage can, and a sink. This was a room she was familiar with, having seen Dr. Morys here for some bad colds and sore throats, and once a sprained ankle. (“Ahh, Nieve no more running for you, I’m afraid,” Dr. Morys had said. Fortunately, he’d winked at her when he said it.)

She heard the voice again, still muffled but louder, so slipped into the consulting room and crept over to the window that overlooked the lane behind the clinic. Outside were three child-sized figures dressed in black leggings and short cloaks, baggy hoods over their heads, obscuring their faces. They were struggling to load a body into the back of the idling ambulance, a body that was wrapped from head to foot like a mummy in gauzy swaths of spider silk. Their captive was fighting hard, squirming and wriggling in an effort to wrench free. Muzzled, the captive’s angry protests were smothered, the voice squashed and unrecognizable. Almost unrecognizable.

Nieve tugged desperately at the window, trying to yank it open. It was jammed shut. The only way out was through the front door. She tore out of the consulting room, ran past the reception desk, and out the door. Without slowing, she turned sharply at the corner of the building and sped down the alley beside the clinic . . . but she was too late! By the time she got to the back lane, the ambulance was pulling away. Frantically, she searched the ground, seizing a rock to throw at it, a last ditch effort to stop them, but already the ambulance was speeding down the lane toward the road that led out of town.

She hurled the rock furiously in its wake.

Mayor Mary! Nieve had failed her, but what could she have done? Not only had she been outnumbered, but the figures themselves, although small, were not children. When the ambulance had peeled away, spinning its tires and spitting gravel, one of the abductors had turned to stare at her. His hood had fallen onto his shoulders revealing a bald head and a clenched, rag-grey face. His yellow eyes, taking her in, were as sharp as pins.