Preface (from The Rings of Saturn)

. . . after my discharge from hospital I began my enquiries about Thomas Browne, who had practised as a doctor in Norwich in the seventeenth century and had left a number of writings that defy all comparison. An entry in the 1911 edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica had told me that Browne’s skull was kept in the museum of the Norfolk & Norwich Hospital. Unequivocal though this claim appeared, my attempts to locate the skull in the very place where until recently I had been a patient met with no success, for none of the ladies and gentlemen of the present administrative staff at the hospital was aware that any such museum existed. Not only did they stare at me in utter incomprehension when I voiced my strange request, but I even had the impression that some of those I asked thought of me as an eccentric crank. Yet it is well known that in the period when public health and hygiene were being reformed and hospitals established, many of these institutions kept museums, or rather chambers of horrors, in which prematurely born, deformed or hydrocephalic foetuses, hypertrophied organs, and other items of a similar nature were preserved in jars of formaldehyde, for medical purposes, and occasionally exhibited to the public. The question was where the things had got to. The local history section of the main library, which has since been destroyed by fire, was unable to give me any information concerning the Norfolk & Norwich Hospital and the whereabouts of Browne’s skull. It was not until I made contact with Anthony Batty Shaw, through Janine, that I obtained the information I was after. Thomas Browne, so Batty Shaw wrote in an article he sent me which he had just published in the Journal of Medical Biography, died in 1682 on his seventy-seventh birthday and was buried in the parish church of St Peter Mancroft in Norwich. There his mortal remains lay undisturbed until 1840, when the coffin was damaged during preparations for another burial in the chancel, and its contents partially exposed. As a result, Browne’s skull and a lock of his hair passed into the possession of one Dr Lubbock, a parish councillor, who in turn left the relics in his will to the hospital museum, where they were put on display amidst various anatomical curiosities until 1921 under a bell jar. It was not until then that St Peter Mancroft’s repeated request for the return of Browne’s skull was acceded to, and, almost a quarter of a millennium after the first burial, a second interment was performed with all due ceremony. Curiously enough, Browne himself, in his famous part-archaeological and part-metaphysical treatise, Urn Burial, offers the most fitting commentary on the subsequent odyssey of his own skull when he writes that to be gnaw’d out of our graves is a tragical abomination. But, he adds, who is to know the fate of his bones, or how often he is to be buried? Thomas

Browne was born in London on the 19th of October 1605, the son of a silk merchant. Little is known of his childhood, and the accounts of his life following completion of his master’s degree at Oxford tell us scarcely anything about the nature of his later medical studies. All we know for certain is that from his twenty-fifth to his twenty-eighth year he attended the universities of Montpellier, Padua and Vienna, then outstanding in the Hippocratic sciences, and that just before returning to England, received a doctorate in medicine from Leiden. In January 1632, while Browne was in Holland, and thus at a time when he was engaging more profoundly with the mysteries of the human body than ever before, the dissection of a corpse was undertaken in public at the Waaggebouw in Amsterdam — the body being that of Adriaan Adriaanszoon alias Aris Kindt, a petty thief of that city who had been hanged for his misdemeanours an hour or so earlier. Although we have no definite evidence for this, it is probable that Browne would have heard of the dissection and was present at the extraordinary event, which Rembrandt depicted in his painting of the Guild of Surgeons, for the anatomy lessons given every year in the depth of winter by Dr Nicolaas Tulp were not only of the greatest interest to a student of medicine but constituted in addition a significant date in the agenda of a society that saw itself as emerging from the darkness into the light. The spectacle, presented before a paying public drawn from the upper classes, was no doubt a demonstration of the undaunted investigative zeal in the new sciences; but it also represented (though this surely would have been refuted) the archaic ritual of dismembering a corpse, of harrowing the flesh of the delinquent even beyond death, a procedure then still part of the ordained punishment. That the anatomy lesson in Amsterdam was about more than a thorough knowledge of the inner organs of the human body is suggested by Rembrandt’s representation of the ceremonial nature of the dissection — the surgeons are in their finest attire, and Dr Tulp is wearing a hat on his head — as well as by the fact that afterwards there was a formal, and in a sense symbolic, banquet. If we stand today before the large canvas of Rembrandt’s The Anatomy Lesson in the Mauritshuis we are standing precisely where those who were present at the dissection in the Waaggebouw stood, and we believe that we see what they saw then: in the foreground, the greenish, prone body of Aris Kindt, his neck broken and his chest risen terribly in rigor mortis. And yet it is debatable whether anyone ever really saw that body, since the art of anatomy, then in its infancy, was not least a way of making the reprobate body invisible. It is somehow odd that Dr Tulp’s colleagues are not looking at Kindt’s body, that their gaze is directed just past it to focus on the open anatomical atlas in which the appalling physical facts are reduced to a diagram, a schematic plan of the human being, such as envisaged by the enthusiastic amateur anatomist René Descartes, who was also, so it is said, present that January morning in the Waaggebouw. In his philosophical investigations, which form one of the principal chapters of the history of subjection, Descartes teaches that one should disregard the flesh, which is beyond our comprehension, and attend to the machine within, to what can fully be understood, be made wholly useful for work, and, in the event of any fault, either repaired or discarded. Though the body is open to contemplation, it is, in a sense, excluded, and in the same way the much admired verisimilitude of Rembrandt’s picture proves on closer examination to be more apparent than real.

Contrary to normal practice, the anatomist shown here has not begun his dissection by opening the abdomen and removing the intestines, which are most prone to putrefaction, but has started (and this too may imply a punitive dimension to the act) by dissecting the offending hand. Now, this hand is most peculiar. It is

not only grotesquely out of proportion compared with the hand closer to us, but it is also anatomically the wrong way round: the exposed tendons, which ought to be those of the left palm, given the position of the thumb, are in fact those of the back of the right hand. In other words, what we are faced with is a transposition taken from the anatomical atlas, evidently without further reflection, that turns this otherwise true-to-life painting (if one may so express it) into a crass misrepresentation at the exact centre point of its meaning, where the incisions are made. It seems inconceivable that we are faced here with an unfortunate blunder. Rather, I believe that there was deliberate intent behind this flaw in the composition. That unshapely hand signifies the violence that has been done to Aris Kindt. It is with him, the victim, and not the Guild that gave Rembrandt his commission, that the painter identifies. His gaze alone is free of Cartesian rigidity. He alone sees that greenish annihilated body, and he alone sees the shadow in the half-open mouth and over the dead man’s eyes.

We have no evidence to tell us from which angle Thomas Browne watched the dissection, if, as I believe, he was among the onlookers in the anatomy theatre in Amsterdam, or indeed what he might have seen there. Perhaps, as Browne says in a later note about the great fog that shrouded large parts of England and Holland on the 27th of November 1674, it was the white mist that rises from within a body opened presently after death, and which during our lifetime, so he adds, clouds our brain when asleep and dreaming. I still recall how my own consciousness was veiled by the same sort of fog as I lay in my hospital room once more after surgery late in the evening. Under the wonderful influence of the painkillers coursing through me, I felt, in my iron-framed bed, like a balloonist floating weightless amidst the mountainous clouds towering on every side. At times the billowing masses would part and I gazed out at the indigo vastness and down into the depths where I supposed the earth to be, a black and impenetrable maze. But in the firmament above were the stars, tiny points of gold speckling the barren wastes. Through the resounding emptiness, my ears caught the voices of the two nurses who took my pulse and from time to time moistened my lips with a small, pink sponge attached to a stick, which reminded me of the Turkish Delight lollipops we used to buy at the fair. Katy and Lizzie were the names of these ministering angels, and I think I have rarely been as elated as I was in their care that night. Of the everyday matters they chatted about I understood very little. All I heard was the rise and fall of their voices, a kind of warbling such as comes from the throats of birds, a perfect, fluting sound, part celestial and part the song of sirens. Of all the things Katy said to Lizzie and Lizzie to Katy, I remember only one odd scrap. I think Katy, or Lizzie, was describing a holiday on Malta where, she said, the Maltese, with a death-defying insouciance quite beyond comprehension, drove neither on the left nor on the right, but always on the shady side of the road. It was not until dawn, when the morning shift relieved the night nurses, that I realized where I was. I became aware again of my body, the insensate foot, and the pain in my back; I heard the rattle of crockery as the hospital’s daily routine started in the corridor; and, as the first light brightened the sky, I saw a vapour trail cross the segment framed by my window. At the time I took that white trail for a good omen, but now, as I look back, I fear it marked the beginning of a fissure that has since riven my life. The aircraft at the tip of the trail was as invisible as the passengers inside it. The invisibility and intangibility of that which moves us remained an unfathomable mystery for Thomas Browne too, who saw our world as no more than a shadow image of another one far beyond. In his thinking and writing he therefore sought to look upon earthly existence, from the things that were closest to him to the spheres of the universe, with the eye of an outsider, one might even say of the creator. His only means of achieving the sublime heights that this endeavour required was a parlous loftiness in his language. In common with other English writers of the seventeenth century, Browne wrote out of the fullness of his erudition, deploying a vast repertoire of quotations and the names of authorities who had gone before, creating complex metaphors and analogies, and constructing labyrinthine sentences that sometimes extend over one or two pages, sentences that resemble processions or a funeral cortège in their sheer ceremonial lavishness. It is true that, because of the immense weight of the impediments he is carrying, Browne’s writing can be held back by the force of gravitation, but when he does succeed in rising higher and higher through the circles of his spiralling prose, borne aloft like a glider on warm currents of air, even today the reader is overcome by a sense of levitation. The greater the distance, the clearer the view: one sees the tiniest of details with the utmost clarity. It is as if one were looking through a reversed opera glass and through a microscope at the same time. And yet, says Browne, all knowledge is enveloped in darkness. What we perceive are no more than isolated lights in the abyss of ignorance, in the shadow-filled edifice of the world. We study the order of things, says Browne, because we cannot grasp their innermost essence. And because it is so, it befits our philosophy to be writ small, using the shorthand and contracted forms of transient Nature, which alone are a reflection of eternity. True to his own prescription, Browne records the patterns which recur in the seemingly infinite diversity of forms; in The Garden of Cyrus, for instance, he draws the quincunx, which is composed by using the

corners of a regular quadrilateral and the point at which its diagonals intersect. Browne identifies this structure everywhere, in animate and inanimate matter: in certain crystalline forms, in starfish and sea urchins, in the vertebrae of mammals and the backbones of birds and fish, in the skins of various species of snake, in the crosswise prints left by quadrupeds, in the physical shapes of caterpillars, butterflies, silkworms and moths, in the root of the water fern, in the seed husks of the sunflower and the Caledonian pine, within young oak shoots or the stem of the horsetail; and in the creations of mankind, in the pyramids of Egypt and the mausoleum of Augustus as in the garden of King Solomon, which was planted with mathematical precision with pomegranate trees and white lilies. Examples might be multiplied without end, says Browne, and one might demonstrate ad infinitum the elegant geometrical designs of Nature; however — thus, with a fine turn of phrase and image, he concludes his treatise — the constellation of the Hyades, the Quincunx of Heaven, is already sinking beneath the horizon, and so ’tis time to close the five ports of knowledge. We are unwilling to spin out our waking thoughts into the phantasmes of sleep; making cables of cobwebs and wildernesses of handsome groves. Besides, he adds, Hippocrates in his notes on sleeplessness has spoken so little of the miracle of plants, that there is scant encouragement to dream of Paradise, not least since in practice we are occupied above all by the abnormalities of creation, be they the deformities produced by sickness or the grotesqueries with which Nature, with an inventiveness scarcely less diseased, fills every vacant space in her atlas. And indeed, while on the one hand the study of Nature today aims to describe a system governed by immutable laws, on the other it delights in drawing our attention to creatures noteworthy for their bizarre physical form or behaviour. Even in Brehm’s Thierleben, a popular nineteenth-century zoological compendium, pride of place is given to the crocodile and the kangaroo, the ant-eater and the armadillo, the seahorse and the pelican; and nowadays we are shown on the television screen a colony of penguins, say, standing motionless through the long dark winter of the Antarctic, with its icy storms, on their feet the eggs laid at a milder time of year. In programmes of this kind, which are called Nature Watch or Survival and are considered particularly educational, one is more likely to see some monster coupling at the bottom of Lake Baikal than an ordinary blackbird. Thomas Browne too was often distracted from his investigations into the isomorphic line of the quincunx by singular phenomena that fired his curiosity, and by work on a comprehensive pathology. He is said to have long kept a bittern in his study in order to find out how this peculiar bird could produce from the depths of its throat such a strange bassoon-like sound, unique in the whole of Nature; and in the Pseudodoxia Epidemica, in which he dispels popular errors and legends, he deals with beings both real and imaginary, such as the chameleon, the salamander, the ostrich, the gryphon and the phoenix, the basilisk, the unicorn, and the amphisbaena, the serpent with two heads. In most cases, Browne refutes the existence of the fabled creatures, but the astonishing monsters that we know to be properly part of the natural world leave us with a suspicion that even the most fantastical beasts might not be mere inventions. At all events, it is clear from Browne’s account that the endless mutations of Nature, which go far beyond any rational limit, and equally the chimaeras produced by our own minds, were as much a source of fascination to him as they were, three-hundred years later, to Jorge Luis Borges, whose Libro de los seres imaginarios was published in Buenos Aires in 1967. Recently I realized that the imaginary beings listed alphabetically in that compendium include the creature Baldanders, whom Simplicius Simplicissimus encounters in the sixth book of Grimmelshausen’s narrative. There, Baldanders is first seen as a stone sculpture lying in a forest, resembling a Germanic hero of old and wearing a Roman soldier’s tunic with a big Swabian bib. Baldanders claims to have come from Paradise, to have always been in Simplicius’s company, unbeknownst to him, and to be unable to quit his side until Simplicius shall have reverted to the clay he is made of. Then, before the very eyes of Simplicius, Baldanders changes into a scribe who writes these lines, and then into a

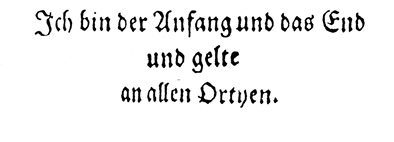

mighty oak, a sow, a sausage, a piece of excrement, a field of clover, a white flower, a mulberry tree, and a silk carpet. Much as in this continuous process of consuming and being consumed, nothing endures, in Thomas Browne’s view. On every new thing there lies already the shadow of annihilation. For the history of every individual, of every social order, indeed of the whole world, does not describe an ever-widening, more and more wonderful arc, but rather follows a course which, once the meridian is reached, leads without fail down into the dark. Knowledge of that descent into the dark, for Browne, is inseparable from his belief in the day of resurrection, when, as in a theatre, the last revolutions are ended and the actors appear once more on stage, to complete and make up the catastrophe of this great piece. As a doctor, who saw disease growing and raging in bodies, he understood mortality better than the flowering of life. To him it seems a miracle that we should last so much as a single day. There is no antidote, he writes, against the opium of time. The winter sun shows how soon the light fades from the ash, how soon night enfolds us. Hour upon hour is added to the sum. Time itself grows old. Pyramids, arches and obelisks are melting pillars of snow. Not even those who have found a place amidst the heavenly constellations have perpetuated their names: Nimrod is lost in Orion, and Osiris in the Dog Star. Indeed, old families last not three oaks. To set one’s name to a work gives no one a title to be remembered, for who knows how many of the best of men have gone without a trace? The iniquity of oblivion blindly scatters her poppyseed and when wretchedness falls upon us one summer’s day like snow, all we wish for is to be forgotten. These are the circles Browne’s thoughts describe, most unremittingly perhaps in the Hydriotaphia or Urn Burial of 1658, a discourse on sepulchral urns found in a field near Walsingham in Norfolk. Drawing upon the most varied of historical and natural historical sources, he expatiates upon the rites we enact when one from our midst sets out on his last journey. Beginning with some examples of sepulture in elephants, cranes, the sepulchral cells of pismires and practice of bees; which civil society carrieth out their dead, and hath exequies, if not interments, he describes the funeral rites of numerous peoples before coming to the Christian religion, which buries the sinful body whole and thus extinguishes the fires once and for all. The almost universal practice of cremation in pre-Christian times should not lead one to conclude, as is often done, that the heathen were ignorant of life beyond death, to show which Browne observes that the funeral pyres were built of sweet fuel, cypress, fir, yew, and other trees perpetually verdant as silent expressions of their surviving hopes. Browne also remarks that, contrary to general belief, it is not difficult to burn a human body: a piece of an old boat burnt Pompey, and the King of Castile burnt large numbers of Saracens with next to no fuel, the fire being visible far and wide. Indeed, he adds, if the burthen of Isaac were sufficient for an holocaust, a man may carry his own pyre. Browne then turns to the strange vessels unearthed from the field near Walsingham. It is astounding, he says, how long these thin-walled clay urns remained intact a yard underground, while the sword and ploughshare passed above them and great buildings, palaces and cloud-high towers crumbled and collapsed. The cremated remains in the urns are examined closely: the ash, the loose teeth, some long roots of quitch, or dog’s grass wreathed about the bones, and the coin intended for the Elysian ferryman. Browne records other objects known to have been placed with the dead, whether as ornament or utensil. His catalogue includes a variety of curiosities: the circumcision knives of Joshua, the ring which belonged to the mistress of Propertius, an ape of agate, a grasshopper, three-hundred golden bees, a blue opal, silver belt buckles and clasps, combs, iron pins, brass plates and brazen nippers to pull away hair, and a brass jew’s-harp that last sounded on the crossing over the black water. The most marvellous item, however, from a Roman urn preserved by Cardinal Farnese, is a drinking glass, so bright it might have been newly blown. For Browne, things of this kind, unspoiled by the passage of time, are symbols of the indestructibility of the human soul assured by scripture, which the physician, firm though he may be in his Christian faith, perhaps secretly doubts. And since the heaviest stone that melancholy can throw at a man is to tell him he is at the end of his nature, Browne scrutinizes that which escaped annihilation for any sign of the mysterious capacity for transmigration he has so often observed in caterpillars and moths. That purple piece of silk he refers to, then, in the urn of Patroclus — what does it mean?

— W. G. SEBALD