Seems like everyone these days wants to train “obliques”. Those cord-like muscles running up the sides of the abdomen are the subject of some kind of gold rush—at least if you buy into the fitness media. It’s impossible to pick up a magazine, skim a training book or watch an ab-gadget infomercial without being beaten around the head with the term obliques. It’s like some kind of ab-training buzzword…like a cake just ain’t complete without frosting, your abs aren’t complete until you’ve worked those obliques.

If you’re anything like me, you find this excessive focus on developing such a minor body part in isolation for purely aesthetic reasons pretty sickening. It reminds us of the narcissism of our species; plus our amazing capacity to waste precious time and energy on insignificant crap. And if the idea itself isn’t bad enough, checking out modern training methods for working the obliques will surely make you to make you want to hurl or put a gun to your skull. The bulk of techniques applied by coaches and personal trainers consist of side crunches, twisting crunches, side cable crunches and similar silly garbage.

This group of popular techniques are both misguided and ineffective. They are misguided, because they attempt to train a small muscle with isolation movements, when that muscle evolved to function as a link in a larger chain. They are ineffective because movements like the crunch aren’t strength exercises—they are low-resistance tension exercises. They make it feel like you’re working, while you are actually producing zero results. (Stop and “tense” your quads for three sets of twenty reps, three times a week. Will they get any bigger? Nope. Any stronger? Nope. It kinda feels like work, but your quads won’t actually change at all, unless you actually bend those knees and start squatting.)

If you really want to strengthen and harden your obliques, you need to work them following the same four tried-and-true principles you would use to effectively work any muscle group. You need to:

• Use bodyweight as resistance

• Apply techniques which integrate the body as a total unit

• Work hard

• Keep moving on to progressively tougher techniques

Use this as a basis for your strength training philosophy, and you will get great results, no matter what muscle group you want to work. Don’t be afraid of getting strong!

This warning—don’t be afraid of getting strong—isn’t nearly as dumb as it might sound. Believe it or not, there are guys and girls in gyms all over the world scared to death of training their obliques hard, for fear that it will thicken their waists, detract from their “V taper” and spoil the symmetry of their physiques. Only one response to that attitude—bulls***!

There are only two things which will bloat out your waistline and give you chunky “love handles”. One is excess body fat. The other is steroid and growth hormone abuse, which will cause all your muscles to gain water and expand the size of your internal organs, swelling your overall midsection. Functional strength training won’t affect your waist size—unless it causes you to lose body fat and become slimmer.

The obliques are small, dense muscles, and naturally working them to maximum strength will cause them to become powerful and sculpted, but it won’t stretch the tape much. Just look at elite martial artists and gymnasts. These men and women need incredibly powerful obliques for their respective disciplines; but take a look at their waists and you’ll see that they are slim, tight, and hard as iron.

Modern gym-rats could take a lesson from these athletes. If you have been brainwashed into doing light, pointless exercises for your obliques, don’t panic, partner. In this chapter I’m going to show you how to get a waist that’s Bruce Lee-strong; no side crunches, cables, rubber bands or ab-gadgets required.

Before we get started, it might be helpful to ask a simple question: do you really need to start performing specific oblique work at all?

If you read the ab-training articles in modern muscle rags, you’ll assume the answer is obviously “yes”. But wait. Hold your horses. Don’t forget that all the muscles of the midsection work together, a bit like a big, muscular girdle. When one of these muscles fires hard, they all have to fire—even if only isometrically. This anatomical reality also applies to the obliques. Your obliques fire when you do bridges, and when you squat—and the harder you work on these exercises, the harder your obliques have to work to keep up.

This effect is enhanced if you perform specific work for the abdomen—particularly leg raises. If a tight, powerful midsection is what you’re looking for, strict hanging leg raises will get the job done. Not only do leg raises work the hell out of your anterior chain, the obliques get a great workout just holding the hips in place. In Convict Conditioning, I also included twisting leg raises as a supplemental variant exercise for those athletes who wanted to amplify the effects of leg raises for their obliques.

In reality, if you are working hard on leg raises and the rest of the Big Six movements detailed in Convict Conditioning, you may not feel the need to give your obliques any specific ancillary work at all. Truth is, they’re already getting a workout from what you are doing.

That said, there will always be sportspeople who need to give their obliques extra specific training for their chosen sport. The muscles of the flank (including the obliques) are responsible for bringing the side of the ribcage and hips closer together, so optimal obliques are essential for any sport that involves kicking or lifting the legs out to the side. Acrobats, skaters and dancers are examples of athletes who need beyond-normal oblique strength. There will also be some hardcore bodyweight athletes for whom mastering leg raises is just not enough—they have to master everything. These brutes will also want to know how to work their obliques right.

Plus, the moves I’m gonna teach ya in this chapter are badass…as cold as ice. They are satisfying as hell to master, and goddam impressive to show off to others. A lot of bodyweight athletes will want to experiment with oblique training for these reasons.

And why not? You pay taxes too, right?

Bridges work the back of your body: hamstrings, glutes, spinal muscles, traps—the posterior chain. Leg raises work the front of your body: abs, hips, deep thigh muscles—the anterior chain. If you are looking for an exercise to work the muscles of the side of your body—the lateral chain—look no further than the human flag.

There are many variations of the flag, but the hardest versions all involve maintaining a straight body out from a vertical base. From this position you look like a flag standing out in the wind—hence the most common name of the exercise. (Though you should know that the term “flag” is not a universal one. Some call it a side or horizontal lever. The athlete who taught me the movement called it the side plank, and I didn’t hear of it referred to as anything else until years later.)

The flag is a wonderful example of a total body exercise. Maintaining this position works the entire lateral chain—not just the obliques, but also the lats under the armpits, the serratus of the ribcage, the intercostals, the hip abductors, and the tensors on the outside of the thigh. The spine and trunk muscles need to be steely to lock everything in place safely. Because the lower leg has to be held up against gravity, the adductor muscles of the inner thigh also get trained by this hold. It also works the upper body hard, because the athlete has to hold onto the base with the arms. For sure, the flag can leave the side of your waist sore for days after you do it, but every muscle in your body has to be strong if you want to have a hope of holding the flag.

How strong is your lateral chain, son?

LATERAL MUSCLED WORKED

BY ALL FLAG TECHNIQUES

The flag is not drawn from modern gymnastics—there are no vertical bases in modern gymnastics, only horizontal bases (think of the floor, vaulting horses, beams and rings, rather than upright poles). The flag is an ancient exercise, and is still seen in disciplines which require a vertical base; Indian pole training (mallakhamb), Chinese pole exercise and circus rope acrobatics are examples where flag progressions are still formally taught. I learnt how to do the human flag where I learnt the rest of my skills—in jail. There are plenty of rails, bars, and fence posts in prison.

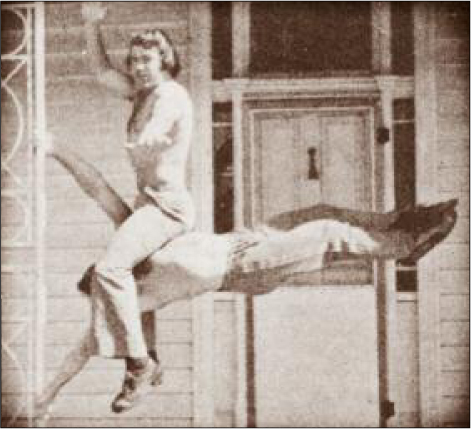

Assorted forms of lateral chain training. From top left: partner calisthenics; rope acrobatics; traditional mallakhamb training; and a circus stunt. (That’s the great Roy Rogers supporting a couple of pals.)

Wherever and whenever you learn the flag, one fact remains true—it’s an incredible strength feat. It needs to be treated with respect. If you don’t approach it progressively, you won’t have a prayer of mastering it properly.

There are two major variations of the human flag hold. One is called the clutch flag, the other is called the press flag. In the clutch flag, you clutch the vertical base—a pole, staff, slim tree trunk, whatever—to your chest, hence the name. In the press flag, you press your body out from the vertical base using straight arms.

Al Kavadlo demonstrates a classic clutch flag. The body is perfectly aligned. As usual, Al’s strength makes difficult holds appear effortless.

Vassili performs a perfect press flag. In this shot, you can really see how the press flag is a total body movement–practically every muscle in the physique is activated. Check the phenomenal back development!

I’m going to show you a series of progressions to help you learn both these variations of the flag hold. The clutch flag is a significantly less demanding version because of the reduced leverage. This makes the clutch flag easier and quicker to learn, but ultimately the press flag delivers greater benefits in terms of lateral chain and total body strength.

Because of the difference in difficulty between these two forms of the flag, I always advise my students to master the clutch flag progressions first—before they try to take on the press flag. This rule of thumb is particularly true for athletes who aren’t used to full body holds (like the regular plank, or elbow lever). Becoming proficient in the clutch flag first will not only systematically strengthen your body and give you a radically reduced chance of injury, it will also make your progression towards the press flag that much quicker if you decide to give it a shot.

True strength is born of the ability to use your body as a unit; and fast muscle growth comes from using the best strength exercises possible. This is why modern training of the “flanks”—or the side waist musculature—is so ass-backwards. Modern exercises focus on isolating the obliques to the maximum degree possible.

Wrong.

You want a powerful, sculpted waist like the ones you see in classical statues? Those statues were carved millennia before the side crunch was dreamt up by whatever idiot was to blame. You know my rallying cry by now, cuz. Ignore modern methods. Find a vertical base and learn the flag instead. With side crunches, you might feel a teeny burn somewhere in your waist. But bust out a flag variation and you will feel all the muscles along the side of your body—neck to lats to ribs to obliques to hips and thighs—clenching like nothing on earth. You’ll know those muscles and tendons are being stimulated, strengthened, and tightened. They won’t have a choice!

If you want to develop your lateral chain muscles to their limit, you’ll need to learn the press flag. But, as always in strength training, learn to walk before you can run. Master the clutch flag first. I’ll show you how to do it in the next chapter.