If the old time prison bodyweight masters had one lesson in common about how to build ferociously strong joints, it would be this: always, always train to generate what Joe Hartigen called “supple strength” in the “sinews”. The old timers all would’ve recognized the concept of supple strength, but because it might mean different things today, I’m going to update the term and call it tension-flexibility. If there’s one key or “secret” to strong tendons and soft tissues, you can find it right here.

What is tension-flexibility?

Tension-flexibility is the capacity of a muscle to remain tensed and strong even though it is stretched, or elongated.

Tendons have evolved to be tensed and powerful when on the stretch. It’s what makes them springy and allows animals (or us) to jump, hop, sprint or perform explosive movements. In nature, if stretched muscles were flaccid and relaxed, most forms of strength and power would be impossible.

This view of “flexibility” is one that modern bodyweight strength athletes and gymnasts will know all about, although it’s very much at odds with the general concept of flexibility found in the everyday fitness world. When most coaches talk about flexibility, they automatically associate it with relaxation. This is largely because passive training methods involve deliberate relaxation techniques. It’s taken for granted that a muscle being stretched needs to be relaxed. But does it?

For sure, for voluntary movement to be possible, the muscles on one side of a joint must contract harder than the opposite side. But it doesn’t follow that the muscles on the other side cannot contract at all. They can tense quite hard, in fact—as long as they’re not tensing harder than the muscles on the opposite side, movement will still occur.

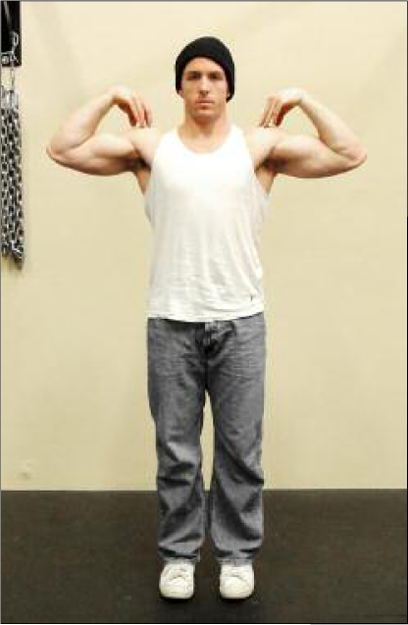

The top picture shows a traditional triceps stretch. The biceps are contracted, the elbows are bent, and the triceps are relaxed.

The picture below shows the top position of a pullup to the chest. At the top of the pullup, the elbows are bent just as acutely as in the “triceps stretch” in the top picture. But although the triceps are lengthened (stretched) at the top of a pullup, they aren’t relaxed.

Just because muscles are stretched, it doesn’t necessarily mean they have to be loose and floppy. They can still be braced and strong as steel.

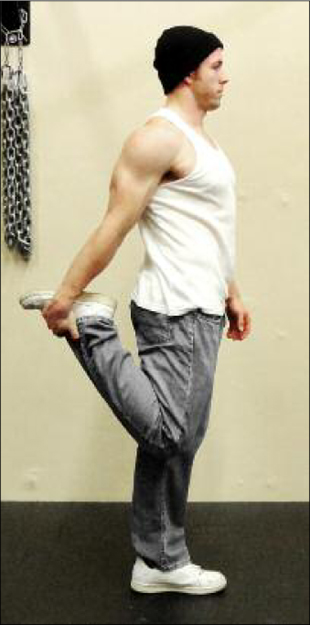

We can think of lots of examples where a muscle needs to be stretched and powerfully contracted simultaneously. Here’s one example. If you wanted to stretch out your quadriceps, and the tendons of the knee, what would you do? Most athletes would probably grab their ankles and pull their heels into their butts, like this:

For sure, this movement is a good example of relaxation-flexibility. The muscles of the quadriceps are being relaxed, and the knee joint is being stretched out. But what if I asked the same athlete to pop down and do a one-leg squat?

The one-leg squat is generally seen as a great strength exercise. It sure as hell isn’t seen as a stretching exercise. But you can see from this picture that Max’s knee is fully bent. In fact, it’s bent even more than when he was deliberately stretching his knee by pulling on his ankle. But despite the fact that the quad and knee tendons are stretched to the limit, they are still generating a lot of tension in this position. In fact, it’s obvious that they must generate a large amount of tension in the fully bent position—if they couldn’t, Max wouldn’t be able to begin moving and stand up straight again. Pressing variations like the uneven pushup are upper body analogs to the squat. In the uneven pushup, the elbows are bent to the max, but the triceps still have to generate high levels of strength and tension to press the athlete up.

It’s not just the quad that’s stretched in this bottom squat position, either. Scan the photo again and catch a look at Max’s right hip. This joint is also being stretched. The glute is stretched so far that his thigh is compressed up against his trunk! But that glute is tensed like a rock to maintain this position, and it it’s about to become the motor that pushes his bodyweight up. The ankle is also highly flexed. So you can see from this simple example that a stretched muscle can also be a very powerful muscle.

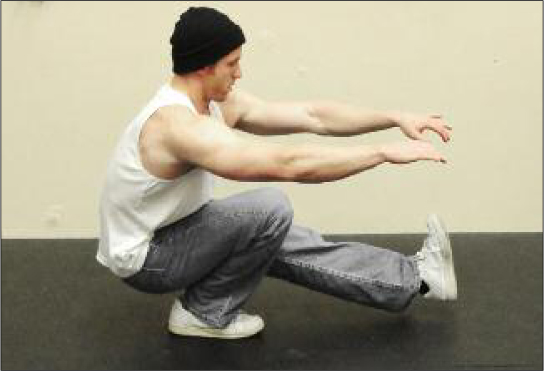

Let me give you another quick example. Look at these two pictures:

In both images, the athlete is stretching out the triceps muscle of the upper arm. The shot on the left is a good example of the kind of relaxed-flexibility found in passive stretching. Max is relaxing his arm muscles and pulling his forearm so that the elbow is bent as much as possible to stretch out his right triceps. In the shot on the right, Max isn’t trying to stretch at all—he’s just doing a close pushup. But you can see that, for the pushup, Max’s elbow is bent to at least the same degree—in fact his bicep is pressing hard on his forearm. Are his triceps relaxed? No way! They are tight and tensed as hell. Even the wrists are bent and stretched, but taut as steel. If Max relaxed his muscles now he’d collapse!

The take-home message? Tension and flexibility aren’t enemies. They go hand-in-hand when it comes to producing strong tendons and powerful joints. Whatever training floats your boat, make sure you gradually build supple strength, or your joints will get proportionately weaker over time—even as your muscles get stronger. This is a dangerous combination.

Many athletes are surprised that strength training in the gym seems to give them aches, pains and injuries, while calisthenics strength training keeps their joints strong, fresh and pain free. There are several reasons for this, but one of the main reasons is that bodyweight exercises develop high levels of tension-flexibility. The basic exercises involve a full range of motion—full squats, close pushups, pullups, etc. Because the extended muscles and tendons are under load in these movements, they are an ideal way to build “supple strength”. Just as important, because Convict Conditioning is divided into gradual, manageable stages (the ten steps) it allows you to build tendon strength slowly. It helps you walk before you can run.

Compare this with a more modern approach, like bodybuilding. Far from taking steps to develop their supple strength, most of these guys do the exact opposite. Instead of building tension-flexibility in their joints by loading their tendons on the stretch, they often avoid full range movements. Instead of full squats, they load up the leg press with huge weights for partial reps. And they all wonder why they have knee problems after just a few months! They shun “supple strength” and favor machines which pump up their muscles using peak contractions, stimulating the muscle bellies but doing nothing for the tendons and joints.

You’ll never see a big-ass bodybuilder perform a one-leg squat or a full one-arm pushup. Their joints would rip in half. These guys pile on muscle as quickly as they can, but fail to realize that the joints and tendons adapt more slowly than the muscles. Instead of smooth, gradual development, everything grows and adapts at the wrong speed. On top of this mess, many bodybuilders have bought into passive flexibility ideas. They train these huge muscles to be loose and limp under force. As a result, when they trip, slip or have to lift something awkward, bad things often happen. Big, impressive muscles do not equal strong, healthy joints.

Compare some popular in-gym movements with their prison bodyweight counterparts, and you’ll get a good idea of why calisthenics movements naturally build tension-flexibility better.

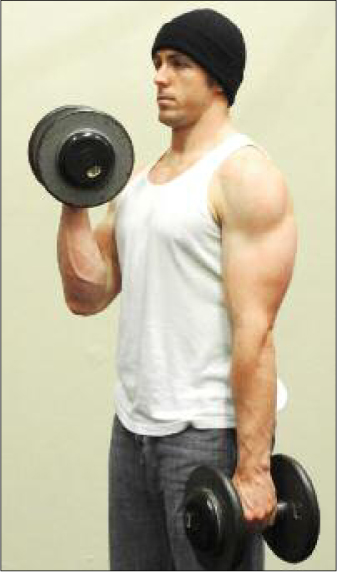

In the gym, most lifters use dumbbell curls to work the biceps. But at the bottom position, where the arm hangs down, the biceps are hardly under tension at all.

Compare this to a properly executed pullup—the arms are kept “soft” meaning that the elbows are slightly, almost imperceptibly, kinked. Not only does this prevent hyperextension, it keeps the elongated biceps under full tension when they are lengthened.

Machines are used more and more in gyms, because they deliver “peak contractions” at the top of a movement. They rarely develop supple strength. Here, an athlete works his anterior shoulder girdle with front cable raises. This will contract (and build) the muscles due to the contraction at the top, but what about the joints? Where’s the tension at the bottom?

Contrast this with a lever pushup—the front delts are forced to retain tension strongly at the bottom, while they are on the stretch. Both the muscles and the joints are developed simultaneously.

I could produce enough examples to fill a whole book, but you get the message. Tension-flexibility is a dead concept for modern trainers.

The idea of “supple strength”—of having muscles and tendons which are strong while stretched—is totally at odds with most modern training methods. Contemporary methods focus on the opposite approach—they teach athletes to relax their muscles while stretching. This is the key to most “passive stretching” methods which pass for flexibility training today.

Modern writers will tell you that stretching and relaxation must go hand in hand. Wrong. Muscles and joints should be stretched under tension. It’s the natural way to stretch. Look at this cat instinctively stretching...is its body floppy and relaxed, or tense and lithe?

Why do modern coaches and trainers teach their athletes to relax during stretching exercises? The reason is obvious. Relaxing while stretching increases the range-of-motion (ROM) of the stretch. It makes it appear that you are more flexible than you really are. But do you really need this “extra” flexibility that relaxation-stretching can give you? For sure, close pushups, deep squats and full pullups contract and extend the muscles over a healthy range-of-motion, but they will never turn you into a contortionist. The question is, do you need this extra artificial range?

Extra ROM from relaxed stretching techniques sounds kinda cool, I admit. But it’s actually a double-edged sword. Relaxing into a flexibility exercise only helps you stretch further because it desensitizes the receptors in your soft tissue—called muscle spindles. Normally the muscle spindles work hard to stop your muscles from overstretching, but gradual relaxed stretching “tricks” them into thinking nothing’s wrong. (Like when you put a frog in a pot of cool water and slowly heat it up to boiling—the frog’s nervous system won’t notice if you do it gradually. The principle is similar.) This desensitization process allows the muscles to stretch further than normal; but it takes time—usually at least several minutes. This loosening up period might help you increase your max ROM, but here’s the nut-punch: you need to perform that loosening up stage again if you want to access the increased ROM in the future. You might see a lot of karate guys pull off impressive kicks in the dojo, but outside on the street, there’s no way they can perform those same moves. So there’s something fishy about all that extra ROM.

The old timers I trained with in jail all shared the same view, maybe for different reasons though. Joe Hartigen, my mentor in SQ, always emphasized that—far from giving you strong joints—relaxed stretching exercises gave you lax, weak joints. I heard similar views from many advanced, knowledgeable bodyweight strength guys stuck behind bars: if you want bulletproof joints, stick with your supple strength training—full range calisthenics movements with bridging and leg raises thrown in. Modern “cutting edge” articles over the last few years talk about stretching like it’s the goddam Holy Grail of injury prevention, but a lot of the old timers believed the exact opposite: relaxed stretching made you more prone to injury!

Ironically, science is only now catching up with those old prison dinosaurs. In an effort to improve the performance of their warriors, the US Army recently conducted an extensive study on the relationship between relaxation-flexibility and injury prevention.* Guess what? Soldiers with the highest levels of flexibility were more prone to injuries than soldiers with average levels of flexibility!

Why do athletes with high levels of relaxation-flexibility get injured more than “tenser” athletes? The answer is that passive stretching methods are based on relaxation under force. They train your muscles to relax under pressure. This is totally contrary to what your body wants to do.

Let me ask you a question: why do joints get injured in the first place? Virtually all joint injuries are caused when ligaments, tendons and soft tissues are stretched too far. These materials can be stretched up to a point, but beyond that point, they rip and split. The results can be devastating.

Knee ligaments split, bursae are torn, shoulder capsules are ripped open, wrists and elbows dislocate and pop out of place. These horrors are all the result of joint tissues being overstretched.

Luckily, Mother Nature is real clever. Your body intuitively understands this risk of overstretching the joints, and has put safety-measures in place to prevent it happening. These natural safety measures are called myotatic reflexes. These reflexes are very ancient, primitive, and totally involuntary. Whenever a muscle is exposed to sudden, shocking forces, it contracts. This is a direct result of the myotatic reflex. The classic “knee-jerk” reflex is an example of this phenomenon. If you strike the tendon of the kneecap, even lightly, the quad muscles will contract to protect the joint.

The patellar tendon (or “knee jerk”) reflex is just one example of a myotatic reflex. When the body goes into protection mode, it tenses.

To put it simply, when your body gets a shock, it tenses. It braces itself, automatically. Do you remember the last time you were walking down the stairs and missed a step? As soon as your body felt the extra jolt of force when you hit the next step, your lower body will have undergone a series of myotatic reflexes—your leg will have tensed. It might be embarrassing to look like a spaz suddenly jerking to attention like that, but trust me, your body does it for a good reason. Tensed muscles absorb shock safely. If you relax when you take a tumble, all that extra force has only one place to go—through the joints. Without muscle and tendon to protect them, joints are fairly easy to injure. Even mild pressure in the wrong direction can easily dislocate a shoulder. If the knee is twisted in the wrong direction by just a few degrees, the ACL can be torn—forever. I could go on and on.

One of the reasons that passive stretching is so dangerous is that it gradually de-activates your body’s vital myotatic reflexes. It replaces tension with relaxation. Great if you are in a hot tub—not so great if you are using your body to actually do something challenging.

A relaxed body is incredibly easy to injure. This is as true for the trunk as for the arms and legs. A single punch can end a fight, if a boxer’s not ready for it—and by “ready” I mean “tensed”. Just ask a karate fighter. For centuries, those dudes have been performing tension exercises. When they get struck, they need their muscles and tendons to be taut and strong to act as armor for their internal organs. Their training supports their myotatic reflexes, and makes them more indestructible in combat. Gymnasts brace for a landing, as do parachutists. Even Olympic divers retain body-tension when they hit the water. In any discipline where big forces are suddenly introduced to the body and the chance of injury is high, athletes are taught how to support their myotatic reflexes by maintaining the right kind of muscular tension.

Don’t believe that flower power bulls*** that a relaxed body is impossible to damage. We’ve all heard the old wives’ tale that drunks rarely get hurt when they fall over, because their bodies are relaxed. It’s just that; an old wives’ tale. Talk to medics who work in the Emergency Room over any given weekend. The vast majority of injuries they are forced to deal with are alcohol related. Falling onto concrete braced is bad enough, but falling relaxed like a drunk is a sure way to really hurt yourself. It might even kill you—many drunken falls result in severe head injuries because the cervical spine is too relaxed to contract and prevent the head from striking asphalt. Excess alcohol can interfere with the nervous system and make your myotatic reflexes sluggish, but this ain’t a good thing. Getting wasted might be fun, but it certainly doesn’t protect you from injury. Just the opposite.

Exercises which generate high levels of tension-flexibility (like one-leg squats) strengthen the joints like nothing else. But you can’t launch into them overnight. Your tendons and soft tissues can and will adapt to these exercises, but you need to give the body the correct preparations—which is the reason why progressive calisthenics begins with gentle steps which allow the tendons to strengthen at their own speed. Rushing into hard “supple strength” exercises, such as close pushups might give the illusion of ability, but athletes who slowly build up to these exercises will have stronger and healthier joints in the long run. Tension-flexibility exercises can be tough. (Which is why many bodybuilders purposefully avoid them.)

Another important point to make is that your muscles need to be elongated under load during tension-flexibility training. But “elongated” does not mean “hyper-extended”. Moving your limbs in their normal range is perfect. You don’t need (or want) to become a contortionist to gain maximum supple strength.

One last word of advice. When training your muscles to be strong while stretched, stick only to those exercises which mimic your natural biomechanics. Steer clear of anything forced or painful. Heavy pressing or pulldowns with a bar behind your neck might stretch your muscles under load, but they also put your rotator cuffs in a vulnerable position. The same is true for most fixed barbell presses and many machine exercises. Avoid.

If you want high levels of supple strength, you don’t need to use fancy machines, bizarre exercises or expensive “supplements”. The best thing you can do is skip the modern stuff and stick to good old-fashioned calisthenics, using bodyweight. Be progressive—begin training the movements in a full-range of motion, but with very little resistance (jackknife squats, wall pushups and vertical pulls are great examples). Build up slowly until you are moving the bulk of your bodyweight (full squats, full pushups and full pullups), then push things further by going on to only one limb (one-leg squats, one-arm pushups and one-arm pullups). This is the approach I learnt in prison, and it not only gives you incredibly powerful joints, it also helps you get that power safely, because you give your tendons and soft tissues time to adapt to the demands of tension-flexibility. Following this kind of “supple strength” routine should be the cornerstone of your training if you want strong, healthy joints.