Over the years inside prison I got hurt plenty of times. I got hurt from fights, work detail and stupid accidents, but the funny thing is I can’t remember getting badly dinged up from my training, despite the fact that I often trained hard every day, seven days a week. A lot of this is down to old school calisthenics—it’s an incredibly safe way to train. Go into any commercial gym and watch guys straining with heavy barbells, dumbbells and weird machines, and you’ll notice they get hurt all the time. In the battle between tender flesh and unforgiving iron, the iron always wins in the end.

No matter how safely you train though, the chances are that you’ll have to work through injuries at some point. The body isn’t a machine. It’s a strange, constantly-altering entity that can be difficult to predict and accommodate. I met a powerlifter once who could deadlift nearly eight-hundred pounds on a bar with no problem, who put his back out picking up his little girl who weighed less than fifty pounds. You can do a one-arm pullup with no pain at all, and then tweak your shoulder brushing your teeth. The body can be weird sometimes. It’s the nature of human life, I guess.

During my three long stretches behind bars, I broke my nose twice, lost three teeth, strained my left bicep, got third degree burns to my right forearm, fractured (and re-cracked) several ribs, dislocated my right kneecap, tore my sacroiliac ligament, split a groin muscle and broke my ankle. I’m not complaining—a lot of guys have come away from jailtime a lot worse than I did. Prison can beat up the body bad, that’s for sure.

These kinds of injuries really interfere with your training, and the problem is magnified by the fact that medical support inside prisons is rarely on a par with the kind of healthcare you get on the outside. Hacks and prison doctors are incredibly wary of inmates seeking medical help—it’s usually an excuse for escape from work detail, or a chance to get access to painkilling drugs (or any drugs). Often convicts with minor injuries are just sent back to their cells to get better pretty much under their own steam. I was always obsessed with my physical conditioning routine—it was the only thing that kept me sane on the inside—and there was no way I was ever going to let something as dumb as being hurt get in the way of that. As a result, I often trained too much; but I also developed a good understanding of how to work around injuries, from the perspective of a guy who trains.

On the outside, you can pick up meds at a 24 hour drugstore, or easily get prescriptions from your doc. Prison docs are less likely to prescribe meds than other healthcare professions. The majority of cons lean towards substance abuse, and no inmate can be trusted to self-medicate.

I’m certainly not a medical expert, by any stretch of the imagination. If you’re on the outside and you get hurt, seek professional attention if you can. But in my experience, doctors often don’t understand the kind of help athletes need when they get dinged. The best guy to ask is usually an athlete—somebody who has been training for years, who has been hurt lots, and had to cope with injuries with very little in the way of surgery, medication, physical therapy or support. As I say, I ain’t no doctor, but I pretty much fit that description.

To help you out as much as possible, I’ve squeezed as much of what I’ve learned as possible into eight general ideas, which, to me, make up the eight laws of healing. Older athletes will recognize a lot of what I’m saying immediately; you young punks will be able to save yourself a lot of trouble and pain by adopting these ideas early on in your careers.

Ready? Okay, lets go:

LAW 1: PROTECT YOURSELF.

The best way to handle an injury is not to get injured in the first place. This seems like a nobrainer, but it’s really not. The vast majority of painful injuries are stupid little things that didn’t need to happen in the first place. Teenagers are the worst offenders here—particularly the “Jackass” generation. Following puberty, kids (okay—male kids) are high on their own newfound sense of physical presence. They feel immortal; invincible. They delight in the rush that comes from doing dangerous things—picking fights, driving too damn quick, playing fast and loose with their health.

After a few scrapes, you begin to realize that the body definitely isn’t invincible—you are not immortal. When you break a rib or a finger, it never feels quite “right” again. If you fully rupture a ligament, that ligament is gone forever; it never grows back. If you dislocate your shoulder, it becomes loose for the rest of your life; it dislocates much easier next time you put it under pressure. (It was a dislocated shoulder that ended Steve Reeves’ bodybuilding career.) Over time, injuries begin to accumulate; even little, minor tears and tweaks, until you are continually plagued by nagging aches and pains and reduced function. Those tough guys who threw themselves around on the high school football field twenty years ago? They are still feeling it now.

You’d think that in the world of strength and fitness, people would be far more into looking after their bodies. In fact, it seems like the reverse is true. Whether to prove a point or just to satisfy their egos, guys in gyms seem prone to continually perform stupid acts that are virtually certain to cripple them somewhere along the line. They load up bone-crushing weights on dangerous exercises like the bench press and the press-behind-neck, bouncing the bar off their ribcages and spines. They hurt their joints with exercises they go back to, week-in, week-out, for years, whittling away their connective tissue and cartilage. They eat and inject all kinds of nasty s*** just to look better than the next guy, while all the time their bodies are breaking down from the inside out.

In the pen, nobody looks out for you. Not really. You might think your gang has your back, but in reality most attacks are launched by one guy on another guy in the same gang. Gang-on-gang violence is a big thing when it happens, but most of the time it doesn’t. Being injured behind bars is not a macho thing like on the outside—it only makes you vulnerable, so real early on you need to cultivate a survivalist approach, an attitude of self-protection. This is the kind of mindset you need to have all the time if you want to make the most of your training and avoid these piled-up injuries that screw with your body and eat away at productive training time. Be perceptive. See dangers coming before they arrive. Avoid stupid, high-risk situations and treat your body nice.

This applies to the choices you make outside your training as much as it does to your conditioning career. Be careful when you train. Look at the following factors:

• Make sure your training environment is secure. Are there items strewn over the floor you could trip over? Etc.

• If you are using objects or equipment to train with, make certain that they are stable and up to the task.

• If you think a technique puts you at risk (of a fall, or hitting your head, for example), don’t do it—find ways to make it safer, or drop it altogether.

• Self-protection is also about how you train. If an exercise hurts—I’m talking injury pain, rather than the discomfort of effort—stop. Alter the exercise so that it no longer hurts, or find an alternative.

Self-protection as a principle continues to function even after you get hurt (God forbid). Immediately following an injury, your first job is to identify what happened and remove yourself from any further danger. Again, this sounds obvious but it isn’t. I knew a guy in my neighborhood who hurt himself doing pullups on an overhead pipe which came loose. He fell down, chipping a bone in his elbow when he slammed into the concrete. Rather than just quitting, he jumped back up in an attempt to finish his set, only to injure his elbow even further. This is a dumb macho attitude—it only makes you weaker in the long run. Be strong and smart.

Illnesses can interfere with your training, the same as injuries. Look after your body with good nutrition and a healthy lifestyle and steer clear of anyone you know who has colds or viruses. A bad cold can put your training back three weeks.

LAW 2: IMMEDIATE THERAPY.

When the time comes that you do get injured—and it probably will come—you need to take immediate steps to speed recovery the second you are out of harm’s way.

Acute injuries to the joints are the bane of an athlete’s life. Most acute soft tissue injuries arrive in the form of either strains or sprains. A sprain is an overstretching of a ligament encasing a joint, whereas a strain is the overstretching of muscle tissue. When strains and sprains occur, the wounded areas go into protective mode and begin to swell up, as the body sends excess fluid to the injured parts to act as a cushion and shock absorber. Unfortunately, sometimes the body doesn’t know when to stop this swelling, and this can be a real problem because swelling interferes with the healing process.

Ouch! Sprained ankles are a classic example of a sprain. You turn your foot under weight, and the ligaments are overstretched and busted up. The body responds by pumping the area with fluid. This acts great as a short-term shock absorber, but it interferes with long-term healing: it can take longer to heal a sprained ankle than a broken leg!

Once you get injured, the best thing you can do is to set about reducing swelling in order to kick-start your body’s healing mechanism. The finest way to do this is to follow the acronym “P.R.I.N.C.E.” which stands for:

PROTECT: This follows on from the first law. If you get injured, you must principally ensure that you prevent further injury. If you have been injured by an exercise, stop the exercise. If you have been injured by an object—such as a dangerous item of machinery—get away from the cause of the injury. Protect yourself immediately by identifying the problem and isolating yourself from it.

REST: The more you move an injured area around, the more it will swell up—so you must rest your injury. If you tear a muscle during an exercise, you need to stop using that muscle for the time being. If you hurt your leg in a fall, don’t attempt to put weight on the leg. This is just common sense. Paradoxically, activity is also vital for healing in the long run (see laws 3 and 4), but right after the injury, rest is more essential.

ICE: When you apply ice to an injury, the cold tissues contract, preventing the excess swelling mentioned above. Ice the injured area using an ice pack, or frozen food. Make sure you have some kind of barrier between yourself and the ice pack—something like a wet towel—to prevent ice burns. A slush bath of ice cubes also works. Ice injuries for no more than fifteen to twenty minutes every two to three hours for the first two days following a strain or sprain.

NSAIDs: NSAIDs are Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs. These are basically medicines which act to reduce swelling in an injured area by inhibiting the chemical processes which cause swelling on a cellular level. As somebody who has had limited access to these meds in jail, I can confirm that when I’ve used them following an injury on the outside, they work wonders. Often when injured, athletes instinctively reach for analgesics—over-the-counter painkillers like paracetamol. This is a mistake. If you have access to them, always appropriately use NSAIDs like ibuprofen or aspirin instead, as they will actually accelerate healing (by reducing swelling) rather than just removing the feeling of pain.

COMPRESSION: Compression is a fundamental and powerful way to reduce excess swelling in tissues. Wrap an injured area in a bandage, nice and snug but not tight enough to disrupt blood flow. Begin wrapping at the point furthest from your heart, and loosen a dressing if it causes pain or if the area below it becomes numb.

ELEVATION: Lifting an injured area up (above the level of your heart) drains excess fluid though the plain old power of gravity. Find some safe and secure way to place your injured limb up on something and just leave it there for a good while—at least half an hour. This is a particularly useful way to reduce swelling during the night, when you will be asleep and unable to apply ice.

Immediate therapy should be applied to joint injuries for several days—up to a week—following acute injury. As soon as the immediate pain and swelling is reducing, an athlete can move to the third law.

LAW 3: KEEP TRAINING YOUR UNINJURED AREAS.

Often athletes instinctively take a layoff after an injury. This is not only unnecessary—it actually slows up your body’s healing process. When you injure yourself, you should get back into training your injury-free body parts as soon as you possibly can.

Let’s say you break your left arm. You can still train your right arm; you can still train your midsection and legs. If you break your legs, you can still find ways to train your torso and arms. If you hurt your lower back, you can still work around the injury to train your limbs. As a general rule of thumb, if you can continue safely working an area, you should do so. Even if you are badly injured and can only work a single body part—maybe your grip, using dynamic tension eagle claw exercises—you should do it.

There are various rewards to this approach. Here’s a shotgun blast of benefits:

• Psychology. Training boosts the self-esteem, an all-too tender quality after an unpleasant injury. It keeps you motivated and helps you to take control, doing something productive and proactive during recovery.

• Routine. Just laying off after an injury messes with your timetable and sense of habit. Getting back into training as soon as you can lessens the likelihood that you will drift away from the fitness lifestyle.

• Crossover effect. The body ultimately works as a system. Training one muscle group automatically transfers strength to other muscles, even if they are seemingly unrelated.

• Fitness maintenance. All athletic qualities are based on a bedrock of basic fitness; attributes such as cardiovascular conditioning, neural communication, cellular health, etc. Continued training will maintain all these qualities.

• Hormonal balance. Athletic training releases useful muscle-building/fat-eating hormones like testosterone. If you quit training due to injury, these hormonal levels plummet.

• Circulation and blood flow. Training the muscles improves circulation around the entire body. This in turn will speed up the healing process (see law 5).

• Stress reduction. Stress compounds like norepinephrine and cortisol can be destructive to the body. Continued training helps you to manage these chemicals, replacing them with painkilling endorphins.

Some people might argue that only working one side of the body—your right arm, if your left is incapacitated, for example—creates strength imbalances. This may be partially true, but there is also some crossover effect, as stated above, and as a result an untrained area will retain a higher level of strength than it otherwise would. Plus, “muscle memory” will allow you to even out your strength symmetry very soon after you get back into bilateral training.

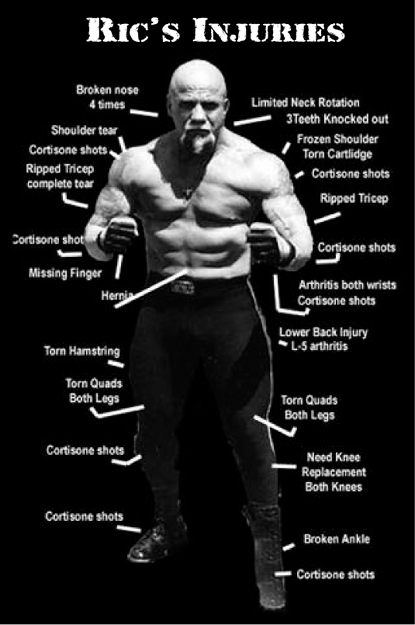

Sometimes you might be unsure of how to train around injuries in this fashion, but where there’s a will there’s a way. You just gotta get creative. When pro wrestler Ric “The Equalizer” Drasin accidentally amputated three fingers in a table-saw accident, he was in the gym the very next day, lifting dumbbells using his palms rather than his fingers. A physical therapist once told me about a paraplegic guy he worked with who used to train his trunk muscles by rocking backwards and forwards while his good arm clung onto a pole. Remember, you don’t need to set records while you’re training around an injury—you just need to get focused and do what you can while being careful not to further injure your preexisting wounds.

And there’s a silver lining to be found here. Often, athletes find that they can radically improve neglected muscle groups when they injure their more highly-developed areas, because the system (both mental and physical) has more energy to invest in them. An arm injury is the perfect opportunity to improve leg strength, for example. Try it and see.

Ric Drasin just takes a lickin’ and keeps on tickin’!

As explained under law 2, the initial bodily response to injury is swelling and inflammation. This swelling must be reduced if you wish to kick-start the healing process. Once the swelling has gone down and the injured soft tissue has begun repairing itself, you should think about training that area again. How long this initial period of rest takes depends upon the severity of the injury—it could take anywhere from a week to a month, or even longer.

This is where a lot of beginners go wrong. Once they hurt themselves—maybe a knee, a shoulder, a wrist—they back away from training that area, to let it heal. Unfortunately, they discover that—six months, a year, even two years later—the acute injury has turned into a nagging, chronic pain. It never really went away. As a result, if they simply stop training an area until it feels 100% again, they will never get better.

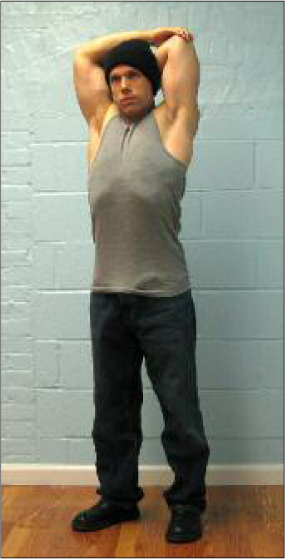

Passive stretching can improve circulation and is good therapy if your body is not yet up to the demands of active stretching or calisthenics.

This happens because a great deal of connective tissue has restricted blood flow, certainly compared to the main muscles. Training not only enhances blood flow, it also sets tissues into a synergistic process of growth and adaptation which is associated with incredibly powerful cellular healing agents. The old timers understood this. They used to advise athletes that injuries had to be “worked out” of joints. This idea, of literally working an injury away seems strange to most people, who are used to resting to try and get rid of an injury. But it works.

There is a caveat, however. “Working out” an injury requires discretion and body wisdom. It’s not a license to launch back into your hardest exercises while you are still hurting. That would only lead to further damage. First of all, you have to wait until swelling has drained from the injured joint or area, ensuring that the healing process has begun. Next, you need to find a movement which involves the damaged joint or muscle, which you can perform without pain. Many therapists—educated from a weight-training perspective—advise the use of light dumbbells to find a movement groove that pumps up a muscle without pain. Being from a calisthenics background, I generally advocate the use of total-body exercises as soon as possible. Bodyweight-type exercises not only train the muscles, they also develop balance, coordination, core strength and functional motion, so you should always favor them over weights work while you are healing. Exercises like pushups and pullups are generally too heavy for rehab purposes, so opt for easier exercises. The movement series in the Convict Conditioning system of calisthenics all begin with a set of three “rehabilitation sequence” exercises, so if you are looking to work your muscles with gentle bodyweight techniques, refer to Convict Conditioning volume one. These milder exercises become progressively harder and are perfect for rehabilitation and physical therapy to help you get back to peak shape—and beyond.

Once you have found a movement you can perform without irritating your injury, focus on increasing your reps. Higher reps will augment blood flow far better than heavier, lower rep work, and this is exactly what you need to speed recovery. Just the simple act of repeatedly contracting healing muscles stretches scar tissue and lessens the likelihood of it spreading. Begin with a shorter, “pumping” range of motion as you are healing, and slowly build to fuller movements over time.

LAW 5: THE POWER OF HEAT.

Once you are able to work a joint again, your recovery will speed up due to the excess blood that training pumps into a wounded area. You can amplify this effect when you are not training, by the use of thermal therapy.

The application of heat to injuries is an incredibly old healing technique. There is evidence that the ancient Egyptians used heat to cure injuries, and the practice of applying heated compresses and poultices goes back long before the early Greeks and Romans wrote about it. Modern-day inmates lean on thermal therapy a great deal, largely because prison medics are so cagey about dishing out painkillers and anti-inflammatory drugs. Whenever I had an injury—or even just an achy joint—I’d heat up some water in my little stinger kettle and pour it into a small rubber heat pack. I found that resting the heat pack on a sore area for twenty minutes relaxed the tight tissues and really helped speed up my healing. It eases pain, too.

When you apply heat to an injured area, the local capillaries naturally expand and enlarge, and this in turn allows more blood into the area. Oxygen and nutrient-rich blood is possibly the most vital factor necessary for healing, and as a result the heat speeds recovery. All that extra blood also loosens up tissues and gently blocks pain sensations from getting back to the brain. Often, relief can come after only a few minutes. Heat therapy is a real wonder.

Get yourself a heat pack to deal with your chronic or acute injuries. I use a fluid-filled water bottle, but several varieties are available on the market, including microwavable gel and bean filled bags. You can even get electrically heated pads. Heat your pack up until it is very warm—bearable, but not burning or painful—and apply it to the point of the injury for twenty minutes on the hour. A good alternative to thermal therapy is sitz therapy, which involves alternating hot and cold temperature on an area (using hot and cold water, packs, etc.). The cold intervals ensure that the body can’t adapt to the heat during a therapy session, and the circulation is really supercharged as a result. Try it with a faucet or showerhead, if you can get the temperature right. Be aware that the cold temperatures can temporarily numb your skin, so be careful not to scald yourself when you apply the heat afterwards.

Because the use of heat increases blood volume in an area, you should never apply heat therapy to an injury that is still swollen or inflamed—heat will only add to the swelling, which is the opposite of what you want. Only apply heat to an injury after the swelling has dissipated, preferably after you are able to work the injured area gently again (see law 4). Muscles and connective tissue can also become inflamed after heavy training, so don’t heat up a tender area immediately after exercise either. In these two special circumstances, ice is the best choice.

LAW 6: BUILD BACK SLOWLY.

Let’s assume it’s been a while since you got hurt, and you have had some success in working the affected area again (law 4). At some point, you’ll want to start heading towards your previous best performances. Note that “heading” doesn’t mean “sprinting”. The body is great at healing injuries, but it requires time. Give it the time it needs. When progressing back to peak shape, it’s wiser to err on the side of going too slowly than going too fast, because if you go too fast and re-injure yourself you’ll wind up taking more time in the long run. Where recovery is concerned, slow and steady wins the race.

Once you can use a good range of motion on your exercises with no pain, you can begin adding resistance by moving onto the harder exercises in the Convict Conditioning system—but do so slowly, and with tender lovin’ care. Don’t jump forwards several steps at a time. Work through each and every step. You can do this faster than it took the first time, but definitely go stage by stage, using your intuition and internal senses to guide you. It’s impossible to give guidelines, because how fast you get back to your best depends on your healing speed and the severity of your injury, but even if you have a very light injury, never leap back to your previous bests. Take it stage by stage. Build up a good head of steam and you’ll be smashing old barriers before you know it.

LAW 7: HAVE FAITH.

Often athletes take great pride in their physical abilities, sometimes centering their entire sense of self-esteem on what they can do with their bodies. When their abilities become curtailed—however temporarily—by an injury, this hits them hard. They can become depressed, despondent, and even suicidal in some cases. I well remember the case of Japanese marathon runner and Olympic medalist Kokichi Tsuburaya, who committed suicide prior to the Mexico City Olympics because his training was hampered by a bad back.

Injuries cause mental stress, which can lead to negativity. If we think we will never recover, we will lose the motivation to conduct proper rehab, and as a result healing slows down to a crawl. This results in stress, which leads to negativity and the cycle repeats itself—it’s a self-fulfilling prophecy. If you really believe you’ll never get better, you probably won’t.

Luckily, the reverse is also true. Believe in yourself, and your chances of recovery skyrocket. Don’t dwell on the negatives of your injury, no matter how bad you think it is. Most of the time, injuries loom much larger in our minds than they really are. The human body is a miracle, and people have been known to recover 100% from even horrific injuries. The sports world is full of athletes who became great again after injuries which should have ended their careers. The annals of medical history are bursting with cases of accident victims who got up and walked despite being told they never would. Have absolute faith in your own future—and you will heal faster.

Focus on the improvements you make on a daily basis, and above all, be positive. A positive attitude releases serotonin, a neurotransmitter that aids relaxation while boosting energy levels; perfect recovery fuel. Positivity stimulates the immune system and releases beta-endorphins which provide pain relief. Recent research even indicates that a good mood can increase circulating human growth hormone—one of the most powerful anabolic healing agents in the body.

There is a very real biology of faith. Tap into it!

LAW 8: HEALING IS A LEARNING PROCESS.

This law is related the previous one, and has a lot to do with staying positive through an injury. We inevitably see getting hurt as a completely bad experience, but this really isn’t true. It’s part of the yin and yang of life that no experience is ever totally negative.

If you perceive injury as exclusively bad, you are missing a trick. I’ve been working out for decades now, and pretty much the only time I ever really learn something new about my body is when I get hurt. Being injured forces an athlete to examine how parts of his or her body work, and encourages us to learn new forms of moving, novel methods of training. If you are paying attention, these little gems of insight will stay with you after you are fully recovered, and can be prize investments in your quest for greater and greater levels of athleticism.

Plus, there’s definitely a deeper message to being injured. Being injured forces us big, ugly, headstrong dudes to stop for a second and gaze down over the battlefield. It gives us a chance to look inside and remember why we started working out, why we need it. Being hurt gives us a potent reminder of how fragile and precious the body really is. In older cultures, healing was seen as a divine thing, holy even. Maybe this is why.

Don’t get me wrong. I’m certainly not saying you need to run around injuring yourself to obtain these profound little life lessons. Always follow law 1 and protect yourself as much as possible; injuries find a body enough without being lent a helping hand. But over the years I’ve learned that being injured—like being incarcerated—needn’t be the end of the world. There’s always a profit to be made of a bad time, if you look hard enough.

During my teens and very early twenties, I didn’t think very much of dealing with injury. It was all just something footballers and old people did. But when I turned twenty-five something happened to me that changed my mind.

The incident in question was the famous 1982 riot in San Quentin. It involved more than a thousand convicts and left many injured real bad. The cause of the riot is unknown. There are a lot of “official” theories, but we knew at the time that most of them were bulls***. Racial and gang attitudes were factors, but no way were they the ultimate cause.

The riot started in the large upper yard. The media at the time spoke in terms of “organized group violence”, but again that was bulls***. The sheer numbers of inmates in the yard, combined with the fact that the violence escalated so quickly made “organization” impossible. It was total chaos. The atmosphere was terrifying, confusing. Adrenaline was running high, and it seemed like a cloud of fear and anger—which to be fair had been bubbling up for weeks—descended over the entire prison. Jostling became pushing, and little, personal fights were started. Friends and nearby gang members quickly joined in, and soon there were brawls all over the yard. In turn these scuffles became the spark which fanned into a flame, and within the course of what seemed like a quarter hour the entire prison was total anarchy. It was crazy.

San Quentin, aerial shot. Even from this height, you can easily see the build up of orange-clad inmates. Trouble’s brewin’.

I had nothing to do with the start of the riot, and I really had no interest in it. But like a lot of convicts I became involved, got sucked in, just because I was out in the yard when things went down. A lot of guys were wounded in the fights that broke out. Inspections have become much tougher since the seventies and eighties, and shanks and basic knives and stilettos made out of pens and toothbrushes were much more common in the joint then than they are now. For some, the riot was a perfect opportunity to facelessly act out little vendettas that had been brewing for years. One guy I knew was unlucky enough to receive a permanent razorblade smile. He was held down by two big gang members, while the third slashed him from ear to ear with a short shiv—a razorblade wound into the shaft of a split pencil.

I guess I was lucky that I didn’t receive any injuries like that. But I did get injured. At some point into the most intense part of the riot, I got the idea into my head that some of my boys were in the north part of the yard, a place where they usually chilled during recreation breaks. I formulated the dumb notion of making my way towards them, fighting through the mass of orange-boilersuited brawlers. And this I did—at least for a few minutes. But eventually the crowd got real dense, and I found myself surrounded by panic-fuelled combat on every side. I began to get nervous as I was pressed and pushed around by the sprawling bodies. I knew that I had made a mistake venturing away from the periphery of the yard where I had started out. Icy fear gripped my insides—I had visions of myself being crushed or trampled to death if things got much worse. I thought about trying to fight my way back out of the riot, but by now I had no idea where I was going.

At this point I was sent sprawling assways as several guys slammed into me, back first. In retrospect, it’s pretty obvious that this wasn’t deliberate. I guess they were just at the tail end of a wave of pressure that started further up the crowd. But at the time I was about thirty pounds of beef lighter than I am now, and I got sent flying into the chest of a weasel-faced little con a few feet behind me. He didn’t like this, and shoved me hard in the shoulder blades, sending me hurtling forwards. By now the blood was rising in my temples, and I made the mistake of turning round and smacking him square in his mean little jaw with a right cross. I’ve no idea whether he went down or not because a split-second later a larger guy—presumably a buddy of Mr Weasel—shoulder barged me from my left. I was quick enough to grab him and turn, so his own momentum slammed him onto the concrete. At some point he had snagged onto my boilersuit though, and I followed him down. I slung my leg over the dude to try and find the purchase to get up, but right at that moment something nasty happened.

I guess there had been more pushing around us, because suddenly, out of nowhere, this hugely fat, bald S.O.B. tripped back and landed right on top of the both of us. It wasn’t his fault, and he landed pretty much flat on his back, but he must have weighed three-hundred pounds and he came down like a Harley or something. I was twisted up badly when he fell on me, and I heard a great big SNAP, even over the shouts of the crowd. I screamed as what felt like a bolt of lightning shot down my left leg. For a split second I got the impression that the chaotic swell packed tightly around us were all going to lose balance and topple down as well, killing us, but luckily no-one else followed him. I scrambled out from under King Kong and hobbled away.

In moments I was in a different part of the yard, but I knew I was hurt. I had no feeling at all in my left leg. It was like a useless chunk of wood.

The riot seemed to last forever, and luckily I survived. But into the night—as the adrenaline and endorphins began to wear off—the pain set in. I realized I had done something very, very bad to myself. The muscles at the rear of my thigh felt like they had been stripped off the bone, blow-torched, then sewn back in. I stupidly tried to walk it off, but the agony was off the scale. The next day my entire lower back had seized up. It was a struggle just to stand up, and I could barely walk even with support. I was convinced I had broken my back or something, and the fear of it made me talk to a hack.

The guards could see I was badly screwed up and I was sent to the prison hospital. Following the big riot, the place was completely packed full of casualties. Limping inside, my hands up against the wall, I remember thinking that it looked like something out of the TV show M*A*S*H. It was that bad. As it turns out, the 1982 riot still holds the dubious record of being the biggest and worst riot in the history of San Quentin, so it’s a pretty safe bet that the hospital hasn’t been so busy either before or since.

Eventually I got to see a couple of doctors who, although competent, were clearly being pretty much pushed beyond their limits by the conditions and workload they had to deal with. After giving my description of what happened, I was prodded, manipulated and had my leg moved round for about fifteen minutes. It was excruciating, and it was a major relief when the examination was over. Even though I’d barely moved, I lay back on the gurney I’d been placed on, soaking in sweat. After consulting with his fellow medic, the older doctor came and spoke to me. “Well,” he said in a southern drawl, “it’s pretty clear what you’ve done sir.” I awaited the verdict in silence. “You’ve torn a ligament in your hip, probably the sacroiliac ligament. Judging by the amount of swelling, you’ve probably tore it clean away.”

Once you can perform the Trifecta movements without hurting yourself, recovery is not far away.

“When will it heal?” I asked. The doctor looked at me with raised eyebrows.

“Ruptured ligaments don’t heal, sir. Once they’re gone, they’re gone. There’s really not much we can do for you. I’ll sign your sheet here, and make sure you get a break from your work details for the foreseeable future.” And with that he turned on his heel to see whoever was next in line.

To my horror, I was given aluminum crutches to help me get back to my block. I could feel the eyes of the inmates burning into me as I slowly, pathetically, clicked and clacked the long, long walk back to my cell. I had felt scared and vulnerable in prison before—everybody does, no matter what they say. But for perhaps the first time in the joint, I had felt the way prey must feel when being eyed up by predators. My tottering trip along the gangways seemed to go on forever, and my thoughts became blacker and blacker with every step. What if this injury was permanent? The doctor had told me that torn ligaments don’t grow back. Would I be limping around with a bum leg forever?

The thought of being a cripple in a hellhole like San Quentin filled me with dread. I knew I would have to get fighting fit again—freakin’ quick—or be perceived as weak. This would mean a whole heap of trouble for me in the future, and I was looking at a lot more time inside at that point. I wasn’t dumb. I knew that recovering from an injury like the one I had would require a lot of physical therapy. I also knew that my chances of getting any such specialist health care inside SQ were between slim and none. I was gonna have to fix this thing myself.

I spent the rest of the week pretty much flat on my back on my bunk, except for mealtimes. I’m a big reader—it’s a valuable hobby to have inside—and when I next got the chance, I tottered to the shabby prison library to look for books on injury rehab. I found two, and they both emphasized the same point about soft tissue injury; namely that it isn’t the actual wound which limits motion after healing—it’s scar tissue. Scar tissue is inevitable following almost any injury, and in many ways it’s a good thing; it knits together damaged anatomical structures, replaces lost function and can even prevent the onset of infection. It is usually stronger than normal tissue, but there is a major downside to this strength—scar tissue is less flexible. This inflexibility makes injured areas tighter than they should be. Scar tissue pulls against surrounding muscle, reducing speed and function and causing joint pain. The only way to make scar tissue more supple is—you guessed it—by proper stretching.

I soon developed a few stretches I was able to do without pain, and I practiced them daily; hourly if I was up to it. This really helped my back and thigh, and in a couple of weeks I was able to resume some upper body calisthenics. After a month I was walking normally, and within six weeks I was able to resume my bodyweight training for legs. This really made my healing speed up. The fresh blood flow and tissue stimulation brought nutrients directly into the injured area so fast I could actually feel myself getting stronger every day. I kept stretching the area, and during my convalescence I read up on the topic, devouring every book I could on flexibility and yoga. After three months my hip was totally back to normal, and I’ve never had a single problem with it since—in fact it is now stronger than it was when I was in my twenties. Being a devotee of calisthenics before the accident definitely gave me a leg up on healing; my muscles were healthy and fit and my metabolism was quicker and more athletic than it would have been otherwise. But the constant stretching out of the injured hip without doubt played a massive part in my recovery.

Like I said, we only really learn something about our bodies when they get injured. When everything’s runnin’ smooth, we don’t pay any attention. The experience of getting hurt in prison was horrible at the time, but I now see it as a blessing; it kick started my study of flexibility.

After this incident I got into stretching more seriously, and began to search out guys inside who could teach me advanced stretching techniques. Prison athletes who stretch are hard to come by, and usually bring their techniques in from the outside. Eventually I hung out with several wrestlers who did a lot of stretching, and quite a few guys who knew a lot of yoga (if that sounds bizarre, remember that San Quentin is in California!). But early on I mostly got to speak to martial artists. I knew several martial artists in prison, and most of them were students of kenpo—a hybrid art similar to karate—which was very big on the West Coast at the time. It’s a little known fact that James Mitose, the guy who actually brought kenpo to America, was imprisoned in Folsom in 1974 after being convicted of murder. Years later, he was moved to San Quentin. He was still there when I arrived, although he died not long afterwards. Sadly, I never even got the chance to meet him; he died just months after I got sent there. I didn’t even discover that he had been incarcerated there until a couple of years after his death.

Left: A young James Mitose works on a striking board.

Right: A mugshot of a much older Mitose, after years of imprisonment in California.

Ironically, I continued passive stretching (see chapter thirteen) after I got back into calisthenics, and guess what? I actually found I got injured more often when I stretched. You don’t need to do passive stretching forever—just as rehab until your body relaxes, heals a little, and gets back to the point where you can do active stretching again without risk. When that time comes, drop passive stretching with a smile on your face. Get back to active stretching, and build up to some calisthenics to build supple strength and blood flow in the joints. This will make you heal at maximum speed.

Talking about healing isn’t sexy. But it’s an absolutely crucial part of any athlete’s experience. Getting big, strong, fast, agile—or whatever you want to be—takes lots of training. It can take a long time. This is only possible if your body is functioning as it should. More athletes quit training due to nagging aches and pains than you would ever believe. The tragedy is that usually quitting is unnecessary—if you have the right knowledge, you can come back from an injury bigger and badder than ever before.

Unfortunately, knowledge about healing the body generally only comes with time and experience—and that translates into a lot of pain. I can’t put my old head on your shoulders, but I can at least try to distill all the tricks I’ve learned in my years of coping with physical wounds behind bars into something you can take away. This is the point of the eight laws. Learn them, take them to heart and you’ll save yourself years of healing time over a lifetime of working out.