Chapter Two

“THE KING OF WATERS, THE SEA-SHOULDERING WHALE”

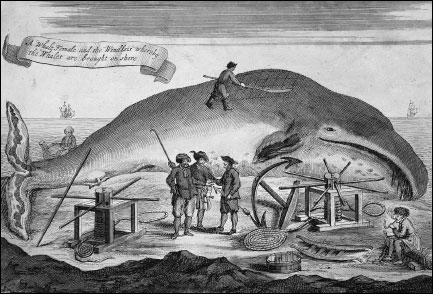

A 1704 ENGRAVING ILLUSTRATING JOHN MONCK’S 1620 VOYAGE TO SPITSBERGEN, SHOWING A “WHALE FEMALE AND THE WINDLAIS WHEREBY THE WHALES ARE BROUGHT ON SHORE.”

AT DAYBREAK ON NOVEMBER 9, 1620, AFTER MORE THAN TWO months of stormy seas, the passengers of the Mayflower sighted shore, which they deemed a “goodly” land that was “woodded to the brinke of the sea.” Unfortunately they also realized that they were in the wrong place. Their patent had permitted them to settle in the vicinity of the Hudson River, but here they were near the tip of Cape Cod, far north of where they were supposed to be. Joyful though they were on reaching land, the Pilgrims decided to coast farther south to finish the journey to which they had originally agreed. But less than a day later, after a harrowing attempt to sail beyond the elbow of the Cape through treacherous shoals, the master turned the Mayflower around and headed back. If they were going to settle in the New World, New England was going to have to be the place, patent or no. To give some semblance of order to their new endeavor, the Pilgrims quickly drafted and signed the Mayflower Compact, in which they announced their intention to “plant the first Colony in the Northerne parts of Virginia,” and bind themselves “together into a civill body politike, for our better ordering and preservation.” No sooner had they completed this historic document, than on the morning of November 11, the weary wanderers dropped anchor in modern-day Provincetown Harbor. Almost immediately, whales surrounded the ship.1

The abundance of whales caused great frustration. “Every day,” wrote one of the passengers, “we saw Whales playing hard by us, of which in that place, if we had instruments and meanes to take them, we might have made a very rich returne, which to our great griefe we wanted. Our master and his mate, and others experienced in fishing, professed we might have made three or foure thousand pounds worth of Oyle.” One whale surfaced near the ship and floated there listlessly, with the sun glinting off its back. Thinking that it might be dead, and apparently wanting proof of this surmise, two men went for their guns and prepared to shoot it. When one of the men fired, his “musket flew in peeces, both stocke and barrell.” Amazingly nobody was hurt, though quite a few people were nearby. The whale, oblivious to the commotion, finally “gave a snuffe and away.”2

It is not surprising that the men of the Mayflower lacked the “instruments and meanes” to pursue whales. While the Pilgrims had always intended to go fishing in the New World, the fish they wanted to catch were not whales, the vaunted “Royal fish,” as they were called in England, but the equally prized though much more diminutive cod.3 It is impossible to know from the Pilgrims’ written accounts what type of whales greeted the Mayflower, but in all likelihood they were right whales. The men seemed to be familiar with the species, and certainly right whales, which had been the mainstay of European whaling for centuries, would have been a familiar sight to men “experienced in fishing.” The men noted, furthermore, that they preferred fishing for these whales than to go “Greenland Whale-fishing.”4 That was a logical comparison to make. Right whales and Greenland, or bowhead, whales, were really the only two species of consequence hunted at the time. And the bowhead had recently taken center stage as the preferred whale for the English, the Dutch, and other nations, all of whom were struggling to gain the upper hand in the whaling grounds off Spitsbergen.5 Assuming, then, that the whales milling about the Mayflower were right whales, the men’s preference to hunt for them made perfect sense. Although right and bowhead whales share many favorable characteristics from the whalemen’s perspective—foremost among them being that they are relatively slow moving, easy to kill, usually float when dead, and provide large amounts of oil and baleen—there is still the issue of location. Even to see, much less hunt, bowheads one had to go to where they lived, and that meant braving the freezing and treacherous waters of the Far North.

The men of the Mayflower not only professed a preference for whaling off Cape Cod but boldly proclaimed that they would “fish for Whale here” the next winter. Before the Pilgrims could make it to the next winter, however, they had to survive the one that lay in store. The weather was getting colder, the food supply on board the Mayflower was dwindling, and many of the passengers were sick, with most suffering “vehement coughs.” Some argued for going no farther and settling on the Cape, not far from where they had first anchored. There was a good harbor there, and the area appeared to be easily defended. Indeed, the search for a better location seemed a foolhardy undertaking now that “the heart of Winter and unseasonable weather” were imminent. There were also the whales to consider. Some of the passengers pointed out that “Cape Cod was like to be a place of good fishing, for we saw daily great Whales of the best kind for oyle and bone, come close aboord our ship, and in fayre weather swim and play about us.” But the majority agreed with Robert Coppin, one of the Mayflower’s mates, that before making such a fateful decision they should explore one more location, “a great Navigable river and good harbour in the other head-land of this bay.” Coppin remembered the place well. Years earlier he and his shipmates came ashore there, and while they were trading with the Indians, one of the “wild men” stole a harpoon, causing the Englishmen to label the place Thievish Harbor. So on December 6, a band of explorers began sailing the Mayflower’s shallop, or small boat, west along the coast of the Cape’s inner arm, toward what they hoped would be Thievish Harbor. At dusk, having made good progress and with their clothes frozen “like coats of Iron,” they headed toward the shore and saw movement on the beach.6

A dozen or so Indians were “busie about a blacke thing,” which the explorers could not quite discern. Seeing the white men approach, the Indians ran back and forth as if gathering their things, and then disappeared into the woods. The explorers pulled ashore farther up the beach, where they spent the night behind a hastily constructed barricade, while sentries kept watch for unwelcome visitors. The next morning the explorers set out to “discover this place” and came upon a “great fish, they called a ‘Grampus,’ dead on the sands.” Two more were found dead at the bottom of the bay under a few feet of water. “They were some five or sixe paces long, and about two inches thicke of fat, and fleshed like a Swine.” Later that day the explorers solved the mystery of the “black thing” that had so interested the Indians. It was another grampus, which the Indians had been cutting into “rands or pieces, about an ell long, and two handfull broad.” In their haste to depart, they had left some pieces behind. Having found so many of these “great fish” that day, the explorers decided to call this place Grampus Bay.7

The grampus would later go by various names, including “blackfish,” “cowfish,” “pothead,” and “puffin pig,” though we know it today as the pilot whale.8 In contrast to right and bowhead whales, the pilot whale has teeth, not baleen, in its mouth; feeds on squid and schooling fish; and is a relatively small whale, reaching twenty feet in length and nearly four tons in weight. Henry David Thoreau described pilot whales, somewhat ungenerously, as being “remarkably simple and lumpish forms for animated creatures, with a blunt round snout or head, whale-like, and simple stiff-looking flippers,” and skin that was “smooth shining black, like India-rubber.”9 The pilot whale’s jawline angles upward toward the back of its mouth, giving it, as another writer called it, “an innocent, smiling expression,” a feature it shares with many of the smaller whales, including dolphins.10

That the Pilgrims were familiar with pilot whales, having a ready name for them, makes sense, since this widely distributed species is found on both sides of the Atlantic. In speculating on how these “great fish” had died, the explorers thought that they had been “cast up at high water, and could not get off for the frost and ice.”11 While this might have kept the pilot whales from returning to open water, and thereby surviving, it is just as likely that these animals had, in effect, killed themselves. This is not to say that the pilot whales sought death in the way that a human being might choose suicide; it’s just that the pilot whales’ behavior sometimes ends in a self-imposed death sentence, and nobody knows why. For centuries humans have been baffled by pilot whales periodically stranding themselves on beaches.12

Scientists have offered many theories to explain this behavior. Perhaps whales strand because they are ill and disoriented, or their navigation systems are disrupted by perturbations in the Earth’s magnetic field or sonar, or they are too aggressive in chasing prey into the shallows, or they simply get lost in the mazelike inlets and bays along the coast and can’t find their way out before the tide recedes. It is even possible that the gregariousness of pilot whales and the strong social cohesion of their pods are partly to blame for some of the larger strandings, especially if after one or more whales become stranded, others in the same pod refuse to leave the beached individuals behind and therefore get stranded themselves. Whatever causes pilot whales to follow this deadly course, this behavior is most prevalent in the waters surrounding Cape Cod, for that long, curvaceous arm of land leads the world in strandings.13

The Pilgrims’ discovery of the pilot whales on the beach elicited a response similar to the one they had had on seeing their first whales from the deck of the Mayflower. This time, though, instead of lacking the instruments to take the whales, they lacked only the “time and meanes” to boil down the whales’ blubber, a process they reckoned would “have yeelded a great deale of oyle.”14 For a second time these newcomers had seen valuable whales yet could not exploit the situation. Thwarted, they returned to the task at hand, finding a good location to settle. The next morning the Pilgrims skirmished with the local Indians and then departed in their shallop, leaving behind a stretch of sand that would thenceforth be known as First Encounter Beach. That night, after losing its rudder and its mast to a savage sea, the crippled shallop, with the explorers hanging on tight and thankful to God, limped into Plymouth Harbor. Although this was not the Thievish Harbor that Coppin had hoped to gain, it was a safe and good harbor, and it became the place where the Pilgrims finally and permanently stepped ashore.15

There is no evidence that any of the men on board the Mayflower went whaling the year following their arrival. Nor is there any indication that any of the colonists who came ashore in New England during the 1620s or early 1630s took up harpoons and got into boats to hunt for whales. During those early years the colonists were consumed by other tasks, such as harvesting fish from coastal waters and crops from the land. While the colonists appear to have had neither the inclination nor the infrastructure to pursue whales at sea, they undoubtedly looked for them on the beach, taking advantage of what the currents and the tides ushered in.16 And they had good reasons for doing so. Whale oil had for centuries proved itself as an excellent illuminant, and the possibility of using such oil in that way must have looked attractive, especially given the lighting alternatives. Burning slivers of wood or pine knots from the pitch pine trees, which grew in great numbers, was a ready option, and one that the colonists and the Indians commonly used. This “candlewood” or “lightwood” was, as one contemporary noted, “so full of the moysture of Turpentine and Pitch, that they burne as cleere as a Torch.”17 But the turpentine and pitch that weren’t consumed during combustion dripped from the wood, leaving behind a sticky, black mass, and candlewood also created thick plumes of sooty smoke; neither of these features commended this fuel for indoor use. And some observers were none too pleased with the light that candlewood threw off, claiming that “it makes the people pale.”18 Another illuminant was oil from the livers of fish, primarily cod. This too was plentiful, but it also smelled rancid and gave off only a middling amount of light.

One lighting alternative that was not readily available to the early colonists was tallow, or animal fat, which could be used to make candles. Tallow was scarce because there were precious few domesticated animals, the main source from which this substance was usually rendered.19 There was, of course, the option of importing tallow candles from England, but that was cost prohibitive for all but the wealthiest individuals. Assessing all their lighting options, the colonists would have viewed whale oil quite favorably. Poured into a crude lamp of the time, or simply pooled in a dish, with a wick sticking out, whale oil provided a dependable and superior light.

The date on which the first colonist cut into a beached whale and boiled its blubber into oil is not known, but by 1635, John Winthrop, the founding governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, wrote in his journal that “Some of our people went to Cape Codd & made some oyle of a whale which was cast on shore: there were 3: or 4: cast, as it seemes there is allmost everye yeare.”20 This enterprising use of whales fit in well with the plans of English promoters of colonization. In 1622 the Council for New England, which had received a royal charter to the region in 1620, sent a report to the king’s son, in which they did their best to showcase the benefits of colonizing New England and thereby transforming it into an economic engine that would admirably serve old England. Turning its attention to the bounty from the sea, the council highlighted the “great numbers of whales, and other merchantable means to raise profit to the industrious inhabitants or diligent traders.”21 The importance of whales to the future prosperity of New England was reconfirmed seven years later, in 1629, when the Massachusetts Bay Company received its charter from the Crown, granting it the rights to a great chunk of land along the coast, as well as to “all Fishes, royall fishes, whales, balan, sturgions, and other fishes of what kind or nature soever that shall…be taken in…the saide seas or waters” in and around Massachusetts Bay.22

However enterprising the colonists were in capitalizing on drift whales, they were not the first Americans to do so. The butchered pilot whale the Pilgrims inspected on First Encounter Beach proved that. The Indians had for many years, and undoubtedly many centuries before that, viewed stranded whales as a commodity, cutting them up and putting parts of the animals to good use, including the meat, blubber, bones, tendons, teeth, flukes, and skin.23 The Indians’ use of drift whales raises a controversial question: Did the Indians hunt for whales at sea? If saying something over and over again makes it true, then the answer is a resounding yes. Numerous authors have stated plainly and without reservation that the Indians were America’s first whalemen.24 One wrote that “the first white men to explore the coast of New England found red whalers at work. In every clan and tribe along the coast were men accustomed to killing whales.”25 Another author was more specific and bold in his conclusions, stating that the American Indians were skilled at killing not just any whales, but sperm whales, the most formidable whale in the ocean.26 The problem with such claims is that there is very little evidence to support them. The only written documentation that Indians in New England pursued whales before the Europeans arrived is the description of the Indian whaling hunt in the book documenting the Waymouth expedition. Although this account is fascinating, and it appears to be a reasonable description of how a whale hunt could be prosecuted, it is not entirely convincing on its own. And, as one historian notes, it “does not appear to be first-hand,” casting further doubt on its reliability.27 As for archaeological support that New England Indians hunted whales, while examples of bone-or stone-tipped spears and harpoons have been unearthed in the region, even some that are thousands of years old, they could have been employed in hunting seals rather than whales.28

The only other early written account of Indians along the east coast of America hunting whales is by Joseph de Acosta in his History of the Indies, published in 1590, which tells an extraordinary story of whaling off Florida. According to Acosta the Indians paddled their canoes alongside a whale, and one of them leaped onto the whale’s neck and thrust “a sharpe and strong stake…into the whales nosthrill [blowhole],” causing the whale to “furiously beate the sea…[and run] into the deepe with great violence, and presently [rise] againe.” The Indian, relying on seemingly supernatural powers, remained firmly attached to the whale’s back, and when it resurfaced, he resumed the attack, driving a second stake into the other blowhole to “take away” the whale’s “breathing.” The Indians then tied a cord around the whale’s tail and towed it into shallow water, where they surrounded the “conquered beast” to collect their “spoils,” cutting its “flesh in peeces…[and] using it for meate.” Although Acosta’s story was repeated many times, few believed it. Not only were the details too fantastic, but the story was not based on an eyewitness account and instead was relayed to Acosta by “expert men.”29

The idea that New England’s Indians went whaling before the colonists arrived is by no means far-fetched. Other native peoples, with tools and skills not dissimilar to the ones available to the eastern tribes, hunted whales well before Europeans were even aware that New England existed. A thousand years ago the Thule Inuits, using bone-tipped harpoons, were whaling in the Canadian Arctic for bowhead and beluga whales from skin-lined boats.30 And the Indians Waymouth encountered had arrows that possibly could have been used to hunt whales, which were described by an eyewitness as being made of ash or witch hazel, “big and long, with three feathers tied on…headed with the long shank bone of a Deere, made very sharpe with two fangs in [the] manner of a harping iron. They have likewise Darts, headed with bone…. These they use very cunningly, to kill fish, fowle and beasts.”31 As for being able to approach a whale in its element and react to and defend against its fury, the coastal Indians of New England possessed the canoe-handling talents to have done so. Still, if the New England Indians had an independent whaling tradition, it most certainly would have continued after the colonists arrived. Yet none of the accounts of the region written by Europeans during the early years of colonization mention Indian whaling. The lack of evidence, of course, does not prove that Indians didn’t have a tradition of whaling, rather it simply means that we cannot say with any confidence that they did.32

While the New England colonists and, most likely, the local Indians focused their attention on drift whales, the Dutch took whaling in America to the next level.33 On December 12, 1630, two Dutch ships, the Walvis (whale) and the Salm (salmon), departed from the Dutch port of Texel and began their voyage to a small parcel of land located at the mouth of the Delaware River, in the vicinity of Cape Henlopen. The Dutch West India Company, the ship’s owners, set two goals for the expedition. The first and primary one was to hunt for whales in and around Delaware Bay, and boil their blubber to produce oil that could be sent back to Holland for use in manufacturing soap. The second goal was to establish a permanent Dutch settlement in the area.

Efforts to establish a settlement on the Delaware coast, in an area that was called Swanendael, or Valley of the Swans, proceeded reasonably well, with the construction of a few buildings and fortifications. But the whaling was a complete bust. Capt. Pieter Heyes, whose job it was to oversee the whaling, abandoned his responsibility, claiming that the whaling season had passed despite the fact that plenty of them were seen swimming just offshore. The only whale that Heyes encountered up close was dead on the beach, from which he and his men extracted a pitifully small amount of oil. Thus, when the Walvis returned to Texel in September 1631, Heyes had almost nothing to show for his trip.

The Dutch West India Company, upset about the outcome of its first whaling expedition, decided to launch another, and placed David de Vries, an accomplished sea captain, in charge. The Walvis was joined by the Eikhoorn (squirrel), and the two ships, after a series of mishaps and delays, finally reached Swanendael in December 1632. After landing and helping to set up the shore-based whaling station, de Vries left on the Eikhoorn to explore the area, while another captain stayed behind on the Walvis to oversee the whaling. From December through March the men of the Walvis harpooned seventeen whales but killed and brought in only seven, and those were the smallest of the bunch, leading de Vries to remark that “the whale fishery is very expensive when such meager fish are caught.”34 De Vries’s disappointment notwithstanding, the men of this expedition made history, becoming the first Europeans to hunt whales successfully in America.

Despite the poor performance of the Dutch, and the limited nature of whaling activities in New England, there was no doubt that whaling was going to play an increasingly important role in America’s development. There were simply too many whales to ignore. Immigrants saw them on their way to America, and settlers saw them from the shore. When a ship traveling to New England in 1629 passed near Cape Sable, off the southern tip of Nova Scotia, the Reverend Francis Higginson wrote in his journal, “In the afternoon we had a cleare sight of many islands and hills by the sea shoare. Now we saw…a great store of great whales puffing up water as they goe, some of them came neere our shipp; this creature did astonish us that saw them not before; their back appeared like a little island.”35 Soon after Higginson arrived in Massachusetts in 1630 he wrote that “the aboundance of Sea-Fish are almost beyond beleeving, and sure I should scarce have belleved it except I had seene it with mine owne Eyes. I saw great store of Whales, and Crampusse.”36 Five years later, on a clear July afternoon, the minister Richard Mather reported seeing off the coast of New England “mighty whales spewing up water in ye ayre, like ye smoake of a chimney, and making ye sea about them white and hoary, as is said [in] Job…of such incredible bigness yt I will never wonder yt ye body of Jonas could bee in ye belly of a whale.”37

And each whale represented a potential path to earning a livelihood. One of the first visitors to note this relationship was William Morrell, an Episcopal clergyman who arrived in Plymouth in 1623. Finding that the locals didn’t lack for religious leadership, Morrell abandoned his first calling and busied himself during the following year by studying the local animals, plants, and people. So smitten was he with his surroundings that he wrote a long and flowery poem about New England, which was published in 1625.38 In a couplet devoted to whales, Morrell captured the primary animating force that would drive future whaling activities in America.

The mighty whale doth in these harbours lye,

Whose oyle the careful mearchant deare will buy.39

About five years after Morrell published his poem, another young Englishman, by the name of William Wood, arrived in Massachusetts. He too wrote down what he saw, and in 1634, after returning to England, he published New England’s Prospect, a relatively short, wide-ranging book about the unfolding colonial experience. In the chapter devoted to fish, Wood included a poem to illustrate the range of commodities that were plentiful off the New England coast. The poem led with the line, “The king of waters, the sea-shouldering whale.”40 And in subsequent years “the king of waters” did not disappoint.