Chapter Thirteen

THE GOLDEN AGE

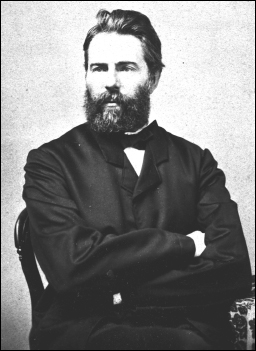

HERMAN MELVILLE IN 1861. HIS GREATEST BOOK, MOBY-DICK, USED THE GOLDEN AGE OF AMERICAN WHALING AS ITS BACKDROP. PHOTOGRAPH BY RODNEY DEWEY.

FROM THE CONCLUSION OF THE WAR OF 1812 THROUGH THE TWILIGHT of the 1850s, the American whaling industry went through a period of unparalleled growth, productivity, and profits. During this golden age, U.S. whaling merchants, unburdened by international conflict and encouraged by the growing domestic and foreign demand, built the largest whaling fleet in history, a veritable armada that peaked at 735 ships in 1846, out of a total of 900 whaleships worldwide.1 The tens of thousands of men who manned these ships traveled millions of miles in their ever-lengthening hunt for leviathans. They pursued and killed hundreds of thousands of sperm, right, bowhead, gray, and humpback whales in the Atlantic, Pacific, Indian, and Arctic Oceans, and in the process discovered new waters and new lands.2 The value of the oil and bone brought back to port made whaling, by the middle of the nineteenth century, the third largest industry, after shoes and cotton, in Massachusetts, and according to one economic analysis, the fifth largest industry in the United States, leading U.S. senator William H. Seward to call whaling an important “source of national wealth.”3 At its height whaling provided a livelihood for seventy thousand people and represented a capital investment of $70 million, while whaleships accounted for roughly one-fifth of the nation’s registered merchant tonnage.4 In 1853, the industry’s most profitable year, the fleet killed more than 8,000 whales to produce 103,000 barrels of sperm oil, 260,000 barrels of whale oil, and 5.7 million pounds of baleen, all of which generated sales of $11 million.5

The golden age is the lens through which people generally view America’s whaling heritage. It is when New Bedford overtook Nantucket as the nation’s whaling capital, and scores of coastal towns launched their own whaling enterprises hoping to cash in on this lucrative trade. It is when the maniacal Captain Ahab met his match and his destiny in the form of Moby-Dick. It is when the whaling industry spawned most of its greatest stories of human drive, perseverance, success, and failure, and when the American whalemen, harpoons in hand, attained mythic status.

On Nantucket the suffering and despondency brought on by the War of 1812 was quickly replaced with almost unbridled joy and optimism come war’s end. The merchants who had managed to hold on through the long and desperate years now sprang to life, and the business of whaling, as Obed Macy observed, “commenced with alacrity.”6 Although the war had claimed half of the island’s whaling fleet, twenty-three vessels still remained, and it seemed as if the entire town had but one goal—to get those vessels and others under construction off to sea. Before the end of 1815 twenty-five whaleships sailed from Nantucket. A contemporary article noted the departure of this small fleet and stated that the war-weary whalemen of New England “have at this moment as much cause of joy as any people under the sun. The produce of their labour is in high demand, and, literally speaking, with every fish they draw out of the sea, they draw up a piece of silver.”7 Sperm and whale oil found ready markets both here and abroad, and by 1819 Nantucket’s whaling fleet had grown to sixty-one vessels. The next year that number rose to seventy-two, and a year later it was approaching ninety.8

One newspaper editorialist, noting Nantucket’s smallness in size and population, and the great losses it suffered during the war, heaped praise on the island and its people. “We are struck with admiration at the invincible hardihood and enterprise of this little active, industrious and friendly community, whose harpoons have penetrated with success every nook and corner of every ocean.”9 When Jared Sparks, who would later become president of Harvard University, arrived in Nantucket harbor in October 1826, he noted that there were “whale ships on every side and hardly a man to be seen on the wharves who had not circumnavigated the globe, and chased a whale, if not slain his victim, in the Broad Pacific.” Although Sparks was impressed by the ten thousand sheep that grazed on the island, he had no doubt that “the absorbing business of Nantucket is the whale fishery. Many had made themselves rich by it, and it gives life to all.”10

In September 1830, when the Loper returned from the Pacific brimming with 2,280 barrels of sperm oil after just fourteen and a half months at sea, the Nantucket Inquirer labeled it the “Greatest Voyage ever made.”11 While other voyages had brought back more oil, none had brought back so much in so little time. The Inquirer’s editor mused that if the captain’s “unparalleled success is the effect of superior skill in the art of whaling, would it not be proper for him to communicate it to others of the same profession, who are now three years in performing exploits for which he requires little more than one?”12 The grateful owners of the Loper staged a sumptuous dinner for the captain and crew, preceded by a triumphant march through the streets of Nantucket. Instead of guns over their shoulders, the men had harpoons and lances as they stepped lively over the cobblestone streets in time with the musical accompaniment. At dinner, glasses were raised and toasts filled the air. To Capt. Obed Starbuck, “No man living has given so much real light to the world, in the same length of time.” To the many whalemen who had died, “May they never want oil to smooth their ways;” and to whaling, “That war which causes no grief, the success of which produces no tears—war with the monsters of the deep.”13 The most interesting toasts of the evening were offered by Absalom Boston, a prominent black Nantucketer and fomer whaleman who shared with the Loper’s nearly all-black crew his reflections on the dismal status of black America, and whose words were “recorded,” as Nathaniel Philbrick notes, “in dubious dialect in the Inquirer.”14 To fellow people of color, Boston shouted out, “May de enemy of our celebration and of African freedom, hab ’ternal itch and no benefit of scratch so long as he lib,” and to the iconic city of Boston, “Where seed of liberty come from—Washington plant him, Lafayette till him, may African reap him.”15 Boston’s toasts were heartily cheered by all, and in particular by the black crewmen, who had the good fortune to be part of a community, given its strong Quaker influences, that had long since decided that black men were not pieces of property but human beings who had a right to all the benefits that entailed. The Loper’s extraordinary voyage was not the only high point for the Nantucket whaling community in 1830. That is also when the Sarah returned after three years at sea, filled to overflowing with 3,497 barrels of sperm oil worth nearly ninety thousand dollars, the largest single voyage ever recorded on the island.16

Nantucket’s whaling fleet built on its success throughout the 1830s and early 1840s, keeping the island’s numerous oil and candle factories busy. William Comstock, writing in 1838, eloquently and in a rather racy manner captured the buoyant mood of the time and the island’s intense connection to whaling. “In the present day, every energy, every thought, and every wish of the Nantucketman is engrossed by Sperm Oil and Candles. No man is entitled to respect among them, who has not struck a whale; or at least, killed a porpoise: and it is a necessary for a young man who would be a successful lover, to go on a voyage around Cape Horn, as it was for a young Knight, in the days of chivalry, to go on a tour of adventures, and soil his maiden arms with blood, before he could aspire to the snowy hand of his mistress, and enjoy the delights of ‘ladye love.’”17

These good times, however, would prove ephemeral. Nantucket’s fall from its lofty perch was the result of many factors, all of which conspired to dampen the hopes of the island’s whaling aristocracy. First in line was the sandbar at the harbor’s mouth. In the early years of Nantucket’s rise as a whaling port, the bar posed no problem to navigation. Although it was a mere seven to eleven feet below the surface, depending on the tides, the bar was deep enough to let the relatively small whaling vessels of the day float over it. But the longer voyages of later years required larger ships, and larger ships, especially when laden with cargo, rode too low in the water to make the same passage. To overcome this obstacle, Nantucket’s whaling merchants employed lighters, or small vessels, to ferry supplies and cargo over the bar, to and from whaleships anchored either beyond the harbor’s mouth or at Edgartown on Martha’s Vineyard, which was increasingly becoming Nantucket’s alternative port. Lightering added time and expense to each voyage, and placed the Nantucketers at a competitive disadvantage with their whaling peers on the mainland, who could load and offload their vessels more efficiently while they were tied up at the wharves. For years, as frustration mounted, Nantucketers debated what to do about their predicament. By the early 1800s popular opinion coalesced around a plan for dredging a channel through the bar, but Nantucket’s appeals to Congress to undertake the project were rejected, and the town’s locally financed dredging effort failed. So, up through the early 1840s the sandbar problem persisted, much to the chagrin of Nantucket’s whalemen. Then, in 1842, Peter Folger Ewer provided a solution.18

Borrowing from earlier Dutch designs, Ewer built two hollow wooden pontoons, connected by sturdy chains, to create a floating dry-dock that could ferry whaling vessels over the bar. The mechanics of these pontoons, which Ewer called “camels” because of their ability to hold great quantities of water and carry heavy loads, were relatively simple. Each pontoon, which was 135 feet long, 19 feet deep, and 29 feet wide, was flat on the top, the bottom, and the outer edge, but contoured on the inner edge to fit the curves of a vessel’s hull. The camels used the same process to transport whaleships both into and out of the harbor. The pontoons would be flooded with seawater, causing them to sink. Once a whaleship was nestled between the pontoons, the camels’ steam engines would then pump the water out of the pontoons, causing the camels and their cargo to float high enough to be towed over the bar. The camels would then be flooded again, thereby sinking and leaving the vessel free to make its way to the wharf or to begin its next voyage.

The camels’ inaugural trial came on September 4, 1842. The guinea-pig vessel, the Phebe, was fully loaded and ready to begin its voyage. The camels were maneuvered into place and the Phebe was lifted high in the water, but once the towing began the weight of the ship proved to be too great. In rapid succession all the chains broke, and as each one went asunder, it created a thunderous report like a cannon firing, which reverberated throughout the town, startling the locals. The Phebe sank back into the water and returned to the wharf for extensive repairs to her copper-sheathed hull, which was greatly damaged by the grating of the chains. This was hardly an auspicious debut, but Ewer forged ahead. He blamed himself for using regular ship’s chains, rather than waiting for the ones designed specifically for the camels. And when those new chains arrived, shortly after the Phebe fiasco, Ewer convinced the owner of the whaleship Constitution to give the camels another try. This time they worked flawlessly, and on September 21, 1842, the Constitution floated over the bar into open water. Less than a month later, the camels passed an even more demanding test when they brought the Peru, laden with sperm whale oil from the Indian Ocean, over the bar. An errand boy living with Ewer’s mother at the time wrote that “more than 1,000 people had assembled to view the novel scene, and someone cried out ‘three cheers for Mr. Ewer.” The New Bedford Weekly Mercury observed that, “The circumstance caused great rejoicing in Nantucket…the bells were rung, and a salute of 100 guns fired.” Another newspaper report proclaimed that “the ultimate success of the Camels is now placed beyond a question. They will be the means of securing to Nantucket much business which has heretofore been done elsewhere.”19

The camels provided a cost-effective alternative to lightering, and scores of whaleships hitched a ride over the bar. But in 1849, just seven years after their introduction, the camels made their last run. The much hoped for revitalization of whaling on Nantucket, which some thought that the camels might spark, failed to materialize. The camels could not overcome larger forces that were driving Nantucket’s whaling fleet toward extinction. Nantucket’s position within the industry was diminished, in part, because its whalemen failed to respond nimbly to changes in demand and to the availability of whales. While their competitors exploited the expanding markets for whale oil and baleen, and sought out new whaling grounds when the old ones had been depleted, Nantucket whalemen continued to hunt sperm whales almost exclusively, and to return to the same grounds year after year even though they were becoming less productive over time.20 The Nantucket fleet’s situation worsened in July 1846 when “the Great Fire” destroyed much of the town’s waterfront, and with it a considerable part of the island’s whaling infrastructure.21 Then, two years later, California beckoned.

ON DECEMBER 5, 1848, President James K. Polk informed the nation that the fantastic rumors emanating from California were true. “The accounts of the abundance of gold in that territory,” Polk said in his annual message to Congress, “are of such extraordinary character as would scarcely command belief were they not corroborated by authentic reports of officers in the public service.”22 Gold fever swept over the East Coast, and whalemen from Nantucket, New Bedford, Sag Harbor, New London, and other whaling ports sailed for the Golden Gate in San Francisco, drawn to California’s rivers and streams by dreams of instant wealth.23 Eastern whaling merchants could do little to stop this hemorrhaging of whaling talent. Even if their men were not leaving to pan for gold, they might still head to California to earn money as carpenters or laborers at rates many times what they could earn on a whaling cruise.24

San Francisco Harbor became a floating graveyard as scores if not hundreds of ships, including a great many whaleships, remained behind as their captains and crews set off for the interior. The interrupted voyage of the Minerva, out of New Bedford, offered evidence of how powerful the lure of gold could be. After whaling in the Pacific, the Minerva’s captain wrote to the ship’s owners about a sudden change of plans. “I went to San Francisco to recruit…but the excitement there in relation to the discovery of gold made it impossible to prevent the crew from running away. Three of the crew in attempting to swim ashore were drowned, and the ship’s company soon became too much reduced to continue the whaling voyage.”25

Nantucket came down with a particularly severe case of gold fever. Hundreds of Nantucket whalemen and more than a dozen ships set sail for California.26 The Nantucket Inquirer fed this fantasy by providing its readers with amazing visions. California “is likely to prove a perfect El Dorado,” wrote the editor. “Portions of it are reputed to be almost paved with gold.”27 Although the Gold Rush quickly faded, the damage to Nantucket’s whaling fleet did not. Many of the whalemen and most of the whaleships that left for California never came back. In 1852 a Nantucket resident painted a depressing scene of the island’s whaling business, noting that it “does not seem to flourish much in this seat of ancient glories…. The Empire which arrived here lately, has been sold at New Bedford. The Daniel Webster is to be sold next week. So they go. Only three whalers are at our wharves…. Of our thirty-two oil manufactories, only four are in operation. The Camels rot on the shore after costing $50,000. To crown all, our hotel is illuminated and perfumed with ‘burning fluid’” (rather than the sperm whale oil that had made Nantucket famous).28 Two years later oil took another hit when gaslight made its first appearance on the island. Throughout the 1850s and 1860s Nantucket’s whaling fleet dwindled to the point where there were only a handful of voyages each year. The end came on November 16, 1869, when the Oak, Nantucket’s last whaling vessel, sailed for the Pacific Ocean, never to return.29

NANTUCKET’S DECLINE as a whaling port coincided with New Bedford’s rise. At the end of the War of 1812, New Bedford was, wrote historian Leonard Ellis, “in a sad condition…. The wheels of industry had long since ceased to move, and her fleet of vessels that had brought wealth and prosperity had been driven from the ocean. Her shops and shipyards were closed, the wharves were lined with dismasted vessels, the port was shut against every enterprise by the close blockade of the enemy, and the citizens wandered about the streets in enforced idleness.”30 But, like Nantucket, New Bedford sprang back quickly. Its whaling merchants expanded their operations by taking advantage of many of the factors that had originally brought Joseph Rotch to the area in 1765—the deep harbor, the heavily wooded forests, and the town’s convenient location on the mainland. New Bedford’s connection to the mushrooming network of railroads inserted the town directly into the stream of commerce, and gave it an efficient means of transporting supplies in and whaling products out. Capitalizing on the growing demand for sperm oil, whale oil, and baleen, New Bedford’s whaling fleet grew at a phenomenal rate, eclipsing Nantucket’s in the 1820s. From that point forward the gap between the two ports rapidly widened, and by 1850 Nantucket’s fleet of 62 paled in comparison with New Bedford’s 288. New Bedford continued its climb until 1857, when it peaked at 329 whaleships, roughly half of the entire American whaling fleet. While New Bedford’s geographical advantages were major factors in its meteoric rise, part of its success was due to the willingness of its whaling captains to hunt for all types of marketable whales wherever they might be, rather than focusing, as Nantucket had, largely on one species or locale.31 Yet another reason for New Bedford’s success had to do with the intensity with which it pursued whaling, bringing with it an extreme devotion to the industry that gave it a competitive edge. As Emerson observed, “New Bedford is not nearer to the whales than New London or Portland, yet they have all the equipment for a whaler ready, and they hug an oil-cask like a brother.”32

America led the world in whaling, and during most of the golden age New Bedford was the nation’s whaling capital. A forest of masts lined the harbor, silently witnessing the stream of ships exiting and entering the port. The waterfront was in a constant state of frenetic action, as armies of men loaded and unloaded the ships with seasoned familiarity, while crowds gathered to celebrate departing and returning whalemen. Shipyards built new ships and repaired those that were worn by the ravages of age. Riggers set thousands of square feet of sails, caulkers filled miles of seams with oakum, and carpenters hammered copper sheathing on the hulls to keep the ravenous and destructive marine boring worms from turning the ship’s wooden skin into a pulpy, porous mass that would allow water to rush in at the slightest provocation.33 The docks and quays were covered with enormous casks of oil and bundles of baleen arranged like sheaves of wheat drying in the sun. Nearly a score of chandlers pressed, molded, and packaged spermaceti candles for the well-to-do, and overflowing warehouses shipped whaling products throughout the United States and the world at large. The streets and alleys abutting the waterfront were lined with the shops of blacksmiths, coopers, and outfitters who supplied the whaling trade; the offices of shipping agents who hired the crews; and the counting rooms of the whaling merchants in which profits and losses were tallied. Farther up, on Johnny Cake Hill, toiled the insurance men who reduced the monetary risks of whaling, and the bankers who helped finance the voyages. Nearby was the Seaman’s Bethel, where whalemen went to pray for forgiveness and protection before heading to sea. The spiritual comfort these men received was tempered by the words on the walls. There, at eye level and ringing the room, were marble cenotaphs that told the tragic tales of whalemen who had been lost at sea.

IN MEMORY OF

CAPT. WM. SWAIN

ASSOCIATE

MASTER OF THE CHRISTOPHER MITCHELL OF NANTUCKET THIS WORTHY MAN, AFTER FASTNING TO A WHALE WAS CARRIED OVERBOARD BY THE LINE, AND DROWNED.

MAY 19TH 1844

IN THE 49TH YR. OF HIS AGE

BE YE ALSO READY: FOR IN SUCH AN HOUR AS YE THINK NOT THE SON OF MAN COMETH.34

In between their devotions, the men couldn’t help but see these remembrances of the dead and wonder if they might be next.

Farther away from the waterfront stood the stately homes of the whaling captains and shipowners. “Nowhere in all America,” wrote Melville, “will you find more patrician-like houses, parks, and gardens more opulent, than in New Bedford…all these brave houses and flowery gardens came from the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans. One and all, they were harpooned and dragged up hither from the bottom of the sea.”35 Melville was not exaggerating. By midcentury New Bedford, whose population had swelled from three thousand in 1830 to more than twenty thousand in the 1850s, was arguably the richest city in the United States per capita.36 Whaling fortunes made by the Rotches, the Russells, the Rodmans, the Morgans, the Delanos, and the Bournes reverberated through the economy, as the men whom the leviathan had made rich invested their wealth not only in whaling but in other businesses and philanthropies as well. And it was not only men who benefited financially from whaling. Hetty Green, who would become the richest woman in America at the beginning of the twentieth century (and be labeled the “Witch of Wall Street” by her detractors), got her start as the main heir to the great New Bedford whaling fortune created by the Howland family.37 But there was also another side to New Bedford—the grimy, dark, and mean streets where the men who manned the whaleships lived. These were what one historian referred to as the “squalid sections,” such as the appropriately named “Hard-Dig,” that housed “the saloons, where delirium and death were sold, [and] the boarding houses, the dance halls and houses where female harpies reigned and vice and violence were rampant.” One of the most notorious destinations in the poorer part of town was the Ark, a whaleship that had been converted into a floating “brothel of the worst character,” replete with a houselike superstructure and rooms to rent.38

With the hub of the rapidly expanding whaling industry in New Bedford, it is not surprising that the country’s first and only newspaper devoted to whaling would be published there. The inaugural issue of the weekly Whalemen’s Shipping List and Merchant’s Transcript hit the streets on March 17, 1843. “It is our intention,” the editors declared, “to present to our readers, a weekly report carefully corrected from the latest advices, of every vessel engaged in the Whaling business from ports of the United States, together with the prices current of our staple commodities, and interesting items of commercial intelligence.” Now, rather than digging through traditional newspapers to glean valuable information about their trade, whalemen could find it all in one place. The Whalemen’s Shipping List also provided a more personal service. “We have been led to believe,” the editors continued, “that a paper of this kind would be interesting to…the parents and wives, the sisters, sweethearts and friends of that vast multitude of men, whose business is upon the mighty deep, and who are for years separated from those to whom they are dear.”39

Although Nantucket and New Bedford were the largest whaling ports during the golden age, they were hardly the only ones. More than sixty other coastal communities pursued whaling at one time or another between the 1820s and the 1850s.40 New London and Sag Harbor headed this list, and in their best years were home to between sixty and seventy whaleships.41 At its height, in the late 1840s, New London’s whaling fleet was second only to New Bedford’s in size.42 New London produced many well-known whaling captains, including the Smith brothers, all five of whom mastered their own ships, completing a combined total of at least thirty-five voyages and earning well over $1 million.43 Perhaps the most famous New London whaling captain was James Monroe Buddington, the man who found the HMS Resolute.

In May 1845 renowned British explorer John Franklin led two ships to the Arctic on an expedition to discover the still-elusive Northwest Passage linking the Atlantic and the Pacific Oceans. Within a couple of months Franklin, his men, and his ships vanished. During one of the subsequent rescue missions, the Resolute, a six-hundred-ton bark, was trapped in the ice, and in May 1854, it was abandoned. Enter Captain Buddington. In May 1855, as master of the George Henry, Buddington left New London on a whaling cruise to the Davis Strait, and on September 10 he spied a vessel in the distance, listing severely to one side. It was the Resolute, and it had drifted in the ice pack more than one thousand miles in sixteen months. Buddington was well aware of the Resolute’s history, and he decided that salvaging it and returning it to port would be far more remunerative than whaling, so he and his men worked to make the Resolute seaworthy again, freeing it of ice and pumping out the water that filled its lower decks. This done, Buddington split his men between the George Henry and the Resolute and took command of the latter. For two months Buddington and his shorthanded crew sailed the battered and rickety Resolute through heavy gales and violent seas before arriving in New London.

The British government honored Buddington’s heroics by announcing that it had waived its rights to the Resolute, and instead wanted to leave the ship to Buddington to dispose of as he saw fit. Congress, however, had a better idea. It purchased the Resolute from the owners of the George Henry for forty thousand dollars, and in a diplomatic effort to improve the United States’ rocky relations with Britain, returned the ship to its original owners. When the Resolute arrived back in England in December 1856, Queen Victoria headed the welcoming party. On the Resolute’s main deck, Capt. Henry J. Hartstene of the U.S. Navy delivered a message from President Franklin Pierce and the American people, stating that the return of the ship was “evidence of a friendly feeling to your sovereignty,…[as well] as a token of love, admiration and respect to Your Majesty personally,” to which the queen responded, “I thank you, sir.”44 While the story ended well for the Americans and the British, it was a bust for Buddington. Although he would forever be remembered as the savior of the Resolute, he claimed that he saw not a dime of the forty thousand dollars windfall the owners of the George Henry had received on account of his actions.45

Sag Harbor, which is situated on the southern tip of Long Island, reached its peak as a whaling center in 1847, when thirty-two ships brought back roughly four thousand barrels of sperm oil, sixty-four thousand barrels of whale oil, and six hundred thousand pounds of baleen.46 James Fenimore Cooper was one of many men who caught whaling fever in Sag Harbor. During a visit to Shelter Island, New York, in 1818 Cooper met one of his wife’s relatives, Charles T. Dering, who was also a shipping merchant. The two got to talking, and Cooper, with no other mode of employment in sight but with plenty of ready cash, joined forces with Dering and other investors to launch a whaling company. The venture not only promised the potential for success, given the whaling industry’s growth in recent years, but it also allowed Cooper to maintain his connection to the sea. Over the next three years Cooper’s whaling company sponsored three voyages out of Sag Harbor, all of which yielded poor returns. Given this track record it is doubtful that Cooper could have remained in the whaling business much longer, but, as it turned out, he didn’t have to. While his ships were faring poorly at sea, Cooper was writing, and in 1821 he achieved his first commercial success, with the publication of The Spy. From that point forward literature became his sole vocation, and he created such classics as The Last of the Mohicans and The Pioneers. In one of his novels, The Sea Lions, published in 1849, Cooper wrote admiringly of Sag Harbor’s whaling heritage, claiming that “Nantucket itself had not more…of the true whaling esprit de corps,” than did this small Long Island community.47

Continuing down the list of whaling ports in the golden age, the number of vessels and voyages quickly diminishes. There were Fairhaven, Provincetown, and Westport, Massachusetts; Stonington, Connecticut; and Warren, Rhode Island—all of which, at their peaks, were home to between twenty-two and fifty whaling vessels each. Next came a raft of cities and towns, including Cold Spring, New York; Bucksport, Maine; Portsmouth, New Hampshire; Gloucester, Massachusetts; Mystic, Connecticut; Newark, New Jersey; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; and Edenton, North Carolina—all of which had only a handful of vessels, and in some cases only one.48 The driving force behind this great explosion up and down the coast was, of course, money. Some of the smaller ports even engaged in a public relations campaign to encourage whaling merchants to relocate. On May 4, 1833, the editors of the Gloucester Telegraph, jealous that Nantucket whalemen were thinking of migrating to Wiscasset, Maine, where the harbor was deep and rarely froze, wrote, “If it is really a fact that any of the good people of Nantucket intend to remove in search of better advantages that are to be found there, we would urge their stopping in at Gloucester. If ever a harbor was intended for extensive business, this is that one. It is comeatable [accessible] in all seasons and at all times; it is spacious and safe for vessels in storms…and, upon a moderate calculation, one thousand whale ships might ride at anchor as slick as grease.”49

Like Gloucester, Wilmington, Delaware, hoped to build a whaling fleet from the ground up.50 In January 1832 a Wilmington merchant wrote a letter to the Delaware Journal in which he urged his peers to get into whaling because of its great profitability. “The eastern cities and towns have pursued whaling for about a century, and in no one instance when it has been undertaken, have they abandoned it—No—they have increased rapidly, and all those that are now pursuing it, are in a prosperous…condition.”51 By late 1833 the prowhaling forces in Wilmington had gained considerable strength, and on October 24 a large crowd of local residents met in city hall to discuss the possibility of establishing a whaling company, and they appointed a committee to further explore the matter. After just eleven days of review, the committee, confidently predicting that whaling in Wilmington would undoubtedly succeed, enthusiastically urged that the Wilmington Whaling Company be created. Wilmington’s leading businessmen rushed to buy stock in the new venture, quickly giving it one hundred thousand dollars of working capital. As historian Kenneth R. Martin points out, to the somewhat naive and eager Wilmingtonians the whaling business seemed relatively straightforward. They would have to purchase a vessel or have one built, hire whaling captains and skeleton crews from one of the New England whaling communities, supplement those crews with eager and youthful men from Delaware, send the ships to the whaling grounds, and wait for the ships’ triumphant and profitable return. And that is exactly what they set out to do.

The first vessel of Wilmington’s fleet was the Ceres, an old and haggard ship out of New Bedford, yet one with some good years left. Along with the Ceres came Capt. Richard Weeden, a seasoned New Bedford whaling captain, and a few of his mates and boatsteerers. Much of the rest of the crew was comprised of wealthy Wilmingtonians, who had little firsthand knowledge of what a whaling voyage entailed, and rather viewed it as a grand adventure that would be great fun. They were what veteran whalemen called “green hands,” landlubbers with no experience on board ship, a fact that became apparent as soon as they tried to leave port on May 6, 1834. Minutes after casting off the Ceres, its crew almost helpless against the tide, grounded in the mud, well within sight of much of the town, which had turned out to cheer on their men and say good-bye but now could only look on with a combination of amusement and concern. The Ceres remained mired for a couple of hours until a steamer pulled it free, and after one more grounding it finally began its cruise for sperm whales in the Pacific.

The trip was a failure, the ship returning in the fall of 1837 not even half full, with less than one thousand barrels of sperm oil on board. Just a few weeks from port, Captain Weeden began to fret about how the good people of Wilmington might react to this extremely poor showing, given that the voyage had began with such high expectations. Rather than let the people down right away, he decided to dupe them. He had his men fill more than one hundred casks with seawater to make the ship ride lower so that it would seem to be heavily laden with oil. That way, when the ship appeared on the horizon and came to dock, those on hand to welcome the whalemen might think that their prayers for a greasy voyage had been answered. Such duplicity prompted one of the crew to comment, “This looks rather blank, deceiving the people of Wilmington with the flattering hopes of our returning home in 30 months, with a full cargo.”52 If any were fooled by this rather silly ploy, they were soon disabused of that notion when they heard that the voyage had lost $5,228. The Wilmington youth who had so enthusiastically signed on to the Ceres were now much the wiser about the rigors and frequent disappointments of whaling, and most of them were just thankful to be home.

While the Ceres was away, the Wilmington Whaling Company had proceeded with its business plan, raising more funds and buying three additional ships, the Lucy Ann, the Superior, and the North America. Then, in 1839, the company added a fifth and final whaleship to its fleet, the Jefferson. Putting aside the Ceres’s first disastrous voyage, the Wilmington Whaling Company’s fleet fared fairly well during the late 1830s, posting a number of profitable if not impressive voyages. But in the early 1840s, the company suffered an abrupt reversal. A major blow was landed when the North America foundered on a reef off Australia, losing its cargo and nearly the entire crew. This, combined with a couple of exceedingly poor voyages, low prices for whale oil, and the lingering effects of a nationwide depression, led the stockholders in 1842 to vote to liquidate the company’s holdings, a task that was completed in 1846. Ironically most of Wilmington’s whaleships were sold to northern whaling ports, whose success Wilmington had so earnestly hoped to emulate. Wilmington was not alone in its failure to capitalize on whaling. Many, though certainly not all, of the minor ports that went whaling during the heady days of the golden age were ultimately unsuccessful. Like Wilmington, these ports optimistically forged ahead only to discover that whaling was a hard and unforgiving business that required more skill than luck.

PART OF THE REASON that American whaling surged ahead during the golden age, notwithstanding the lackluster performance of many of the minor ports, was that American whalemen were simply the best at what they did. In 1843 the Merchants’ Magazine and Commercial Review proudly proclaimed, “The enterprise and success of this fishery, as carried on in American ships, totally disables any other nation from competing with them.”53 And of all the nations that were thus disabled, none was more so than the British. The historic rivalry between Britain and America evaporated as the British whaling fleet, a major player in whaling between the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812, faded from view. British whaleships, which had larger crews, higher costs, and less whaling talent on board, failed to compete with their American counterparts. The Americans caught more whales in less time, undercut the British in world markets by offering the best prices, and did a better job of seeking out and exploiting new whaling grounds. And the British government’s decision, in 1824, to end its long-standing policy of subsidizing the whaling fleet, only hastened, even if just by a little bit, the fleet’s demise.54 In a letter to the London Times in 1846, an Englishman who served nearly six years on board American whaleships pulled no punches in telling his fellow citizens exactly why the Americans were so much better at whaling than the British. “A few words will explain it,—the greater cost of fitting out whalers here, the drunkenness, incapacity, and want of energy of the masters and crews”—all of which were traits that he claimed the Americans didn’t share. “I have little sympathy for the Americans,” the writer continued, “for as a body, I do not believe you could well find a more dishonest people, but their energy in bringing the trade to the pitch it has arrived at, deserves the highest encomium.”55

The explosive growth of the American whaling industry generated an equally explosive demand for labor. In the mid-1850s, New Bedford whaleships alone employed ten thousand seamen, with all the other ports accounting for another ten thousand. Supplying this quantity of bodies was no easy task. The captains and officers were usually hired directly by the shipowners or shipping agents, while the latter were responsible for recruiting the crews. To get men in the door, the agents advertised positions in newspapers, at public establishments, and on the streets. The pitch was always optimistic, like this one:

LANDSMEN WANTED!!

One thousand stout young men, Americans, wanted for the fleet of whaleships, now fitting out for the North and South Pacific fisheries. Extra chances given to Coopers, Carpenters, and Blacksmiths. None but industrious, young men with good recommendations, taken. Such will have superior chances for advancement. Outfits, to the amount of Seventy-Five Dollars furnished to each individual before proceeding to sea. Persons desirous to avail themselves of the present splendid opportunity of seeing the world and at the same time acquiring a profitable business, will do well to make early application to the undersigned.56

Exciting and encouraging words such as these camouflaged a less than “splendid” reality. Whaleship owners, so desperate for labor, rarely had the luxury of focusing on recommendations or the upstanding nature of the applicants. In the mid-1800s “industrious young men” had plenty of shoreside opportunities that were both less dangerous and more remunerative than becoming a whaleman. So the owners were often forced to take what they could get, which was usually green hands who were not infrequently some combination of penniless, delinquent, or drunk.57 The quality of recruits, or more accurately the lack thereof, was a constant source of irritation in the industry, as an article from a Nantucket newspaper in 1836 makes clear: “Too many ungovernable lads, runaways from parental authority, or candidates for corrective treatment, too many vagabonds just from the clutches of the police of European and American cities—too many convicts…are suffered to enlist in this service…. The whale fishery shall not be converted into a mere engine for the repair of cracked reputations and the chastisement of those against the reception of whom even the jail doors revolt.”58 There were also, to be sure, whalemen who were, as one magazine called them, “hardy, intelligent sons of our soil,” who came from fine families, had decent if not stellar educations, and simply chose to sign up believing it would be an adventure, a means of character building, or simply a potentially rewarding job, but they were a distinct minority.59 The seventy-five-dollar signing bonus recruits received sounded generous until one realized that it was only an advance against wages, and from that amount the men would have to pay for clothes, food, and other supplies. As for seeing the world, if that meant gazing on seemingly endless stretches of ocean, then it was true enough that a whaleman would see a good portion of the world. But if by seeing the world one meant experiencing exciting stretches of terra firma, then a whaling voyage was the last place one wanted to be.

To ensnare recruits agents would usually echo the advertisements’ message and focus on the positive attributes of whaling, even if these virtues where partially or wholly fictitious. “These shipping agents were,” observed historian Elmo Paul Hohman, “marvels of suave deceit and shameless misrepresentation, if contemporary accounts of their methods may be credited. False promises and fluent mendacity were resorted to whenever it seemed advisable.”60 A whaleman in the late 1840s wrote of how “the runaway young man from the country is entrapped [by an agent]; stories are told him, which he, from his want of knowledge readily believes, and thus becomes an easy victim to the wiles of those heartless men who get their living by selling men for a term of years, uncertain in their number, at five dollars a head.”61 Samuel Eliot Morison told of a Boston agent who, after expounding on the “imaginary joys” of whaling to a Maine plowboy, “concluded confidentially: ‘Now, Hiram, I’ll be honest with yer. When yer out in the boats chasin’ whales, yer git yer mince-pie cold!’”62 A duplicitous agent out of New York devised a particularly ingenious scheme of recruiting. He hired a con artist to befriend young men new to the city and encourage them to go whaling with a compelling pitch. First the con artist would say that he was going on a whaling voyage out of New Bedford and that he was leaving the next day on a steamer headed for that port. The con artist would then plead with the newcomer to join him, so that they could share the adventure. Finally, to seal the deal, the con artist would assure his new best friend that there were great profits to be made in whaling—at least “a thousand dollars” for three years’ work. Duly impressed, the newcomer would march down to the agent’s office, accompanied by his new best friend, and sign on. Since agents only got paid if the men they signed actually showed up for duty, the New York agent had to make sure that his new recruit made it to his ship. The agent would, therefore, have the recruit spend the evening and the next morning with the con artist, all the while talking animatedly about the voyage to come. But when the new recruit finally got on board the steamer headed for New Bedford, he would soon discover that his putative friend had fast disappeared. Only then did the recruit realize that he “had been gulled.”63 The ploys used by agents to keep their recruits in line ranged from keeping them under close surveillance to, in extreme cases, forcibly delivering the men to the ship even if upon further reflection the men no longer wanted to ship out. Despite such tactics the agents didn’t always get their men. Some recruits, sobered by the reality of their impending departure and, perhaps, clearer visions of the whaling life, failed to show up. Others were yanked away at the last minute by relatives who wanted to keep impetuous and wide-eyed young men from making a major life mistake.64

While the captains and mates, for the most part, were still pulled from the ranks of white Yankee stock, the men who served under them were a polyglot mixture of white and black Americans, Pacific islanders, Portuguese, Azoreans, Creoles, Cape Verdeans, Peruvians, New Zealanders, West Indians, Colombians, and a smattering of Europeans. According to one nineteenth-century observer, “A more heterogeneous group of men has never assembled in so small a space than is always found in the forecastle of a New Bedford sperm whaler.”65 Some of the crew were picked up en route to the whaling grounds, and in many instances this was part of the plan, with the captains stopping in foreign ports expressly to hire new hands. In other cases, however, the captains were forced to make such layovers because of the need to replenish their crew as result of desertions along the way or the loss of men due to injury or death. Many of the foreigners who were thus enlisted into whaling chose to settle in American ports rather than return to their homelands, creating cultural enclaves where English was a second language, if it was spoken at all.

A whaling voyage was a unique opportunity for black men. In a country that still condoned slavery, shipping out as a deckhand on a whaleship provided a black man with a rare measure of dignity and self-worth.66 At sea the color of one’s skin was less important than the skills one possessed and their contribution to the success of the trip. As one black seaman put it, “There is not that nice distinction made in whaling as there is in the naval and merchant services. A coloured man is only known and looked upon as a man, and is promoted in rank according to his ability and skill to perform the same duties as a white man.”67 Just as important to the black whaleman’s sense of pride was the fact that he received equal pay for equal work.68 This is not to suggest that whaleships were bastions of equality and brotherhood among men. There were still many whites who despised their black shipmates, even as they relied on them for their lives and livelihood. As one whaleman from Kentucky, who firmly believed in the rectitude of slavery, noted, “It was…particularly galling to my feelings to be compelled to live in the forecastle with a brutal negro, who, conscious that he was upon an equality with the sailors, presumed upon his equality to a degree that was insufferable.”69

A few black men nonetheless became officers on whaleships, and some, such as Absalom Boston, the man who so heartily toasted the Loper’s black crew on their triumphant return to Nantucket in 1830, even became captains. Born on the island in 1785, Boston, a third-generation Nantucketer, was raised in the section of the island known as “New Guinea,” a name that reflected the African roots of many who lived there.70 His grandparents, who likely arrived on Nantucket in the mid-1700s, had been slaves who were later freed by their owner, and his uncle, Prince Boston, was the man who gained some measure of fame when William Rotch paid him, and not his alleged owner, directly for his work on the whaling sloop Friendship. Absalom Boston pursued the life of a laborer and a mariner, and in 1822, when he was thirty-seven, he took command of the Industry, a whaleship owned and crewed entirely by black men. This ship full of “coloured tars” was, as one of the crew commented, “quite strange.”71 The Industry fared miserably, at least as far as whaling went, returning to Nantucket within six months with a paltry seventy barrels of oil. This failure appears not to have bothered the crew much, and one of them even penned an admiring verse in honor of their leader.

Here is health to Captain Boston

His officers and crew

And if he gets another craft

To sea with him I’ll go.72

Boston never did go to sea again, becoming instead a successful merchant and landowner, and one of the most respected and wealthy blacks on Nantucket.

There was also another side to the blacks’ relationship with whaling. To some slaves, and possibly a considerable number, whaling was viewed as a means of escape. That was the case for John Thompson, who, around 1840, when questioned about his background by the captain of a whaling ship he was on, responded, “I am a fugitive slave from Maryland, and have a family in Philadelphia; but fearing to remain there any longer, I thought I would go a whaling voyage, as being [a] place where I stood least chance of being arrested by slave hunters.”73 To other slaves whaleships became prisons, as did the Fame, which left New London in 1844 on a routine whaling voyage to the Pacific. Two years later, after both the captain and the first mate died, the second mate, Anthony Marks, took command of the ship. While maintaining the outward appearance of a whaling cruise, Marks took the ship to the east coast of Africa, picked up 530 slaves, and delivered them in five months’ time to Cape Frio, Brazil, collecting forty thousand dollars for his efforts.74 Whaleships were particularly well suited for a barbarous conversion to slaving. Their cavernous holds had room for many people, and the tryworks provided a built-in galley, capable of cooking large amounts of food to feed the human cargo. Most convenient to those engaging in this even then reprehensible business was that a whaleship carrying slaves below decks looked like nothing more than what it purported to be. Faced with the potential of earning a windfall for such heinous work, a small number of whaling captains and owners turned their ships into “slavers in disguise,” as historian Kevin Reilly has called them. While some of these men operated without interference, others were caught and successfully prosecuted for participating in this illegal trade.75

NO MATTER WHICH PORT they sailed from, the whaleships of the golden age shared many similarities. And there is no better example of a typical whaleship of the time than the 314-ton Charles W. Morgan, which was built in New Bedford and christened on July 21, 1841.76 On the day of the ship’s launching, the principal owner and namesake, Charles Waln Morgan, wrote in his diary of “his elegant new ship,” and how “about half the town and a great show of ladies” had witnessed the event.77 From the bluff bow to the squared-off stern the Morgan was about 105 feet long. It was broad of beam, measuring 28 feet wide, and had a draft of nearly 18 feet when fully loaded. A good part of its hull was constructed of live oak, a species that ranges from Virginia to Texas and was prized for its strength and reserved for use in the best ships of the day.78 The Morgan’s three masts were shrouded in a dizzying array of ropes and studded with a phalanx of yards from which the white sails were suspended and held taut in the wind. The mainmast towered 100 feet above the deck and was topped by a fully exposed wooden platform with waist-high iron hoops, on which the men spent countless hours, totaling months on a long cruise, staring toward the horizon in search of spouting whales as far as eight miles away. On either side of the Morgan, beyond the main deck’s rails, were a series of long, curved wooden arms, called davits, from which five whaleboats hung, clearly identifying the Morgan as a whaleship.

Below the main deck was the tween deck, which housed the captain’s quarters, the officer’s quarters and mess, the blubber room, and steerage—where the boatsteerers as well as the cooper, cook, steward, carpenter, sailmaker, and blacksmith slept. Within the curves of the bow was the cramped forecastle, or foc’sle as it was usually called, which had bunk beds for as many as twenty-four men and boys along its perimeter. Below the living quarters and the blubber room was the hold, where the food and water were stored as well as the casks of oil and the baleen, along with other supplies.79 At maximum capacity the Morgan held roughly three thousand barrels, or about ninety thousand gallons of oil.

Most merchantmen viewed the wide-bodied, blunt-nosed, and square-ended whaleships with disdain, condescendingly referring to them as “blubber hunters,” “spouters,” or “stinkers,” and claiming that they were “built by the mile and cut off in lengths as you want ’em.”80 But this view entirely missed the point that whaleships, like the whaleboats they carried, were perfectly designed for the tasks they had to perform. “As a vessel,” Hohman pointed out, the whaleship “was signally lacking in the grace, speed, and slender feminine beauty of the clipper; but in staunch seaworthiness, in bulldog battling with wind, wave, and whale, and in the range and seeming endlessness of her voyages she was the peer of any craft afloat.”81 Merchantmen also had few good things to say about whalemen. One such critic, on boarding a whaleship, noted that “Her captain was a slab-sided, shamble-legged Quaker, in a suit of brown, with a broad-brimmed hat, and sneaking about decks, like a sheep, with his head down; and the men looked more like fishermen and farmers than they did like sailors.”82 Here again the critique was too harsh. Where merchantmen often sailed set routes over and over again, and achieved success in part through familiarity, whalemen were forever shifting their course in the elusive search for whales. Although whaleships were not as fast as merchant ships, they still had to go true, and it took considerable skill to sail them for years at a time, in good weather and bad, with and against mighty currents, through uncharted seas, and over treacherous shoals and into tight harbors. While many of the crew on whaleships were a shabby lot, they quickly learned how to handle themselves ably aboard ship, and whaling captains and their mates were quite accomplished seamen, often more capable than the merchant sailors who derided them.

WHALING CAPTAINS LIKED to return to the whaling grounds where they had been successful in the past, but as the number of whaling voyages increased along with the number of whales killed, many of the historically productive areas were depleted. This boom-and-bust cycle, which was no stranger to the industry, forced whalemen to seek out new grounds. One of the first such discoveries during the Golden Age were the fabled offshore grounds, which lay one thousand miles from the Peruvian coast, and were found in 1818 by Capt. Edmund Gardner of the Nantucket whaleship Globe. Gardner’s discovery was not an accident. After months of frustration cruising the “onshore” grounds off South America, which had been hammered by whalemen for years, Gardner decided to sail west. His gamble paid off handsomely. The offshore grounds were teeming with sperm whales, which for many years would provide whalemen with brilliant returns. When Gardner returned to Nantucket in 1820, with 2,090 barrels of sperm oil aboard, his fellow islanders were shocked and buoyed by his success, because just a year earlier, the Independence had returned from the “onshore” grounds with only 1,388 barrels of sperm oil, leading its captain, George Swain, to assert confidently that never again would a ship to the Pacific fill its hold with oil.83 In subsequent years American whalemen discovered other productive whaling grounds, including ones off Japan (1820), Zanzibar (1828), Kodiak (1835), Kamchatka (1843), and in the Okhotsk Sea (1847).84 The most important of all the new grounds, however, were those in the Arctic Ocean, and the first whaling captain to sail into this forbidding frozen region was Thomas Welcome Roys.

In 1847 Roys was given command of the Superior, a relatively small whaling vessel out of Sag Harbor. His instructions from the owners were to sail to the South Atlantic and hopefully return full within ten months, but Roys had other plans. In 1845, while laid up in a Siberian town, recuperating from a violent encounter with the fluke end of a right whale, Roys had heard from a Russian naval officer that the waters north of the Bering Strait were brimming with an unusual species of whale. Intrigued, Roys purchased some Russian naval charts, and when he returned to Sag Harbor he read accounts of Arctic explorers and found that they too had seen whales, which were referred to as “polar whales.” Now, with the Superior under his command, Roys planned to find out if these tales were true. Roys hid his intentions from the owners of the Superior, for he knew that they would veto the idea, and while hunting for whales in the South Atlantic he didn’t let on to his crew that their voyage would be anything other than routine. Finally, after the better part of a year, with little to show for his efforts, Roys decided to execute his plan. Stopping off in Hobart, Tasmania, Roys sent a letter to the owners, letting them know that he was sailing for the Bering Strait and, ultimately the Arctic Ocean, commenting that if they never heard from him again, at least “they would know where [he] went.”85

When his crew finally figured out where they were headed, they panicked. No whaleship had ever sailed into the Arctic Ocean, and they didn’t want to be the ones to blaze the trail. Faced with this unrest, Roys temporarily aborted his plan and had the Superior sail, instead, in the Bering Sea, south of the strait, looking for right whales. After a few weeks of this, Roys turned the bow of the Superior north again and sailed for the strait, the fears of his crew notwithstanding. Roys knew well the fate that might befall him if his gamble didn’t pay out. “There is a heavy responsibility,” he later wrote, “resting on the master who shall dare cruise different from the known grounds, as it will not only be his death stroke if he does not succeed, but the whole of his officers and crew will unite to put him down.”86

Roys’s courage and his faith in his abilities and intuition were hard won, and he was fast becoming a legendary figure in whaling circles. Only thirty-two at the time of the Superior’s voyage, Roys had already had a whaling career that spanned fifteen years and numerous voyages, each one a financial success. Then there was the oft-told and perhaps apocryphal tale of his ride on a whale’s back. While chasing right whales in the northern Pacific, the story began, Roys was dragged overboard by a tangled line. No sooner had he gotten free of the line than a whale rose out of the water beneath him and he found himself straddling the whale’s slippery back. He then jumped onto another whale’s back, fell in the water, and was swatted by the flukes of yet a third whale, the impact of which sent Roys flying back into his boat, where he immediately grabbed his lance and killed all three of his tormentors.87 A man who lived through that certainly wouldn’t shy away from a challenge, especially when there was the potential for great profits.

The Superior entered the strait on July 15, 1848. When the first mate, Jim Eldredge, took his bearings, he assumed that his calculations were incorrect. They couldn’t be that far north. Roys assured Eldredge that there was no mistake; they were indeed in the Arctic Ocean. “Great God,” screamed Eldredge, “where are you going with the ship? I never heard of a whale ship in that latitude before! We shall all be lost!”88 Overcome, Eldredge ran to his bunk and started sobbing. News of the ship’s location quickly spread throughout the crew, all of whom begged Roys to turn around. Roys stood his ground, and soon he noticed a great number of whales about the ship. The officers labeled them humpbacks, which were not worth catching, but Roys disagreed. These whales matched the description of the whales Roys had heard about, and he thought they might be polar whales, so he ordered the whaleboats lowered. Although his men were, according to Roys, “not inclined to meddle with the ‘new fangled monster’ as they called him,” they overcame their trepidation and soon harpooned a whale, which immediately dived and “swam along the bottom for a full 50 minutes,” long enough for Roys to begin wondering whether he “was fast to something that breathed water instead of air and might remain down a week if he liked.”89 The whale finally surfaced dead and was brought alongside the ship, with many of the crew members still insisting that it was a humpback. The cutting in and trying out, however, disabused them of that notion. The whale’s baleen was twelve feet long and its blubber produced 120 barrels of oil. This was no humpback, nor was it a right whale, which it somewhat resembled. Roys’s hunch was correct. It was a polar whale—actually a bowhead—and by killing it he and his men earned the distinction of becoming the first commercial whalemen to meet with success in the Arctic Ocean.90

Roys sailed the Superior 250 miles beyond the strait, “cruised from continent to continent,” and then looped back through the strait on August 27. During that time he and his men, who were still expecting disaster to strike at any moment, took eleven whales and filled the hold to capacity with sixteen hundred barrels of oil. Since that far north the sun never fully sets in summer, the Superior’s whaleboats operated around the clock, with the first whale being killed at midnight. So much blubber was brought on board that, once lit, the flames of the try-pots were not extinguished until the final whale was processed. While the whaling was phenomenally productive, it was not easy. Roys wrote, “On account of powerful currents, thick fogs, the near vicinity of land and ice, combined with the imperfection of charts, and want of information respecting this region, I found it both difficult and dangerous to get oil, although there are plenty of whales.” And some of those whales were colossal, yielding upward of two hundred barrels of oil. Then there was the one that Roys didn’t kill because it was “too large” and he didn’t think that the Superior was big enough or had the equipment necessary to cut into it properly. This “King of the Arctic Ocean,” was, the men reckoned, the largest whale any of them had ever seen, and they thought it would yield more than three hundred barrels of oil.91

When the Superior finally docked in Honolulu on October 4, 1848, word of its remarkable cruise spread quickly, and as whalemen have always done, they rushed to make their claim on the new whaling grounds. In the following year no fewer than fifty whaleships ventured north. Log entries for the Ocmulgee, out of Holmes Hole, Massachusetts, on Martha’s Vineyard, provide a glimpse of the tremendous bounty shared by the Arctic fleet that year.

|

July 25 |

“Plenty of whales in sight, but all hands too busy even to look at them.” |

|

July 26 |

“Blubber-logged and plenty of whales in sight.” |

|

July 27 |

“The same.” |

|

July 28 |

“Blubber-logged, but were obliged to cool down six hours for the want of casks. Whales aplenty.” |

|

July 29 |

“Blubber-logged and whales in every direction.”92 |

Part of the excitement resulted from the size of the bowheads. The biggest did, as Roys and his men had estimated, yield more than 300 barrels of oil, and the average was about 150, which still far outstripped sperms and rights, which averaged 25 and 60 barrels respectively.93 And in each of the bowhead’s mouths were thousands of pounds of long and valuable baleen.94 In 1850 more than 130 whaleships were hunting on the Arctic grounds, but they didn’t fare nearly as well as their predecessors. The whales were definitely becoming scarcer, prompting one “Polar Whale” to write a letter to the Honolulu Friend, pleading for restraint. The editors noted that they were “somewhat surprised that a member of the whale-family should condescend to make his appeal through our columns,” but were nonetheless “honored by the compliment.” The rather lengthy letter offered a particularly cogent if not self-serving argument, which was highly unusual, coming as it did in an era when few, if any, people spoke up against the ravages of whaling.

“The knowing old inhabitants of this sea have recently held a meeting,” the letter began, “to consult respecting our safety, and in some way or another, if possible, to avert the doom that seems to await all of the whale Genus throughout the world.” The Polar Whale had thought he and his peers were safe in the Arctic, far away from man, but still the whaleships came, and as a result, large numbers of polar whales had had been “murdered in ‘cold’ blood.’” His race, he continued, was no match for “the Nortons, the Tabers, the Coffins, the Coxs, the Smiths, the Halseys, and the other families of whale-killers,” and he worried that, if the hunting did not stop, soon none of his kind would be left. “I write in behalf of my butchered and dying species,” the letter concluded, and “I appeal to the friends of the whole race of whales. Must we all be murdered…. Must our race become extinct? Will no friends and allies arise and revenge our wrongs?…I am known among our enemies as the ‘Bow-Head,’ but I belong to the Old Greenland family. Yours till death, POLAR WHALE.”95

Despite the Polar Whale’s plea, whalemen did not stop their assaults on bowheads, or rights or spermacetis for that matter, and the numbers of whales continued to drop. Seeing the stocks dwindle, a few whalemen began to worry about the viability of their livelihood, with one writing, “The poor whale is doomed to utter extermination, or at least, so near to it that too few will remain to tempt the cupidity of man.”96 But whatever reservations whalemen might have had about the future, they kept on whaling with their characteristic drive and determination.

THE FARTHER WHALEMEN went in pursuit of whales, the longer the voyages became, to the point where the average trip lasted almost four years.97 Some whalemen were able to joke about the length of their cruises. A popular story told of a California clipper ship passing near a whaleship off Cape Horn, whose crew appeared to be old, haggard men with wrinkled faces and shaggy beards. A man on board the clipper yelled, “How long from port?” to which one of the apparently geriatric whalemen responded, “we don’t remember, but we were young men when we started!”98 Humor notwithstanding, whalemen didn’t like these long voyages, but they had no choice in the matter. Sailing halfway around the world, and then roaming about in search of the telltale spouts of an ever-diminishing population of whales took a huge amount of time, and most whaling captains chose to stay out longer rather than come home with a poor catch or, worse, a clean ship.99 Capt. Leonard Gifford, of the whaleship Hope, typified this perspective, writing to his fiancée in 1853, after cruising the Pacific for two years, “If I am not fortunate I shall be shure to take another year for if I live to reach home no man shall be able to say by me thear goes a fellow that brought home a broken voyage.” Unfortunately for Gifford and his fiancée, he was far too optimistic. Rather than one more year, Gifford took another three and a half years to make a good trip, not returning to New Bedford until April 1857. Gifford’s desire to avoid a broken voyage was so strong because he knew that captains who failed to perform well were often forced to find another line of work, not only because the owners had lost faith in their abilities but also because crews didn’t want to serve under captains who had earned a “bad name,” and were thought to be unlucky or unskilled or both.100

One idea that would have shortened whaling voyages greatly never got off the ground: namely, to cut a canal across the Isthmus of Darien (modern-day Panama). Writing in November 1822, Samuel Haynes Jenks, the editor of the Nantucket Inquirer, noted that “the practicability of cutting a canal across the Isthmus of Darien, seems to be acquiring daily strength.” Such a project would, Jenks noted, greatly benefit all whalemen. “The subduction of thousands of miles from the length of a voyage to the South Sea, merely by excavating a channel of perhaps only twenty miles, is a matter of the utmost moment to those concerned in the Whale Fishery—a saving of at least one half the time and expense of a voyage, and a total escape from the dangers which attend the doubling of Cape Horn, would be the results.” Pointing out that other forms of commerce would likewise benefit from such a canal, Jenks urged that “every government on the globe” should unite behind this plan, and that the United States government, in particular, should begin the “topographical prerequisites” necessary to evaluate its feasibility.101 But no action was taken, and the plan remained just that. Although Jenks and other supporters of the canal were disappointed, the editor of the New Bedford Mercury was not. He opposed the canal, fearing that it would increase the number of ships, which would in turn lead to a situation in which “there would soon be no whales in the Pacific.”102 Almost another hundred years would go by before there was a canal across Panama, coming far too late to be of much help to American whalemen.

Many whalemen spent more time at sea than they did at home, which led to an unusual sense of time, as evidenced by this apocryphal interchange between a whaling captain and his wife, which made the rounds on Nantucket.

“Dear Ezra:

Where did you put the axe?

Love, Martha.”

Fourteen months later came the reply:

“Dear Martha:

What did you want the axe for?

Love, Ezra.”

A year later came another letter:

“Dear Ezra:

Never mind about the axe. What did you do with the hammer?

Love, Martha.”103

Nathaniel Hawthorne, in one of his “Twice-Told Tales,” echoed this theme when he reflected on the odd married life of a whaling captain from Martha’s Vineyard who hired a sculptor to carve a headstone for his dear departed wife. “So much of this storm-beaten widower’s life,” Hawthorne observed, “had been tossed away on distant seas, that out of twenty years of matrimony he had spent scarce three, and those at scattered intervals, beneath his own roof. Thus the wife of his youth, though she died in his and her declining age, retained the bridal dewdrops fresh around her memory.”104

The long separations meant that the men on whaleships missed many of the important milestones of life, including the births and deaths of friends and relatives, and it was not unusual for a whaleman to return home only to be introduced to a son or daughter he had never seen. Whaling families were able to maintain some semblance of communication by sending letters, but like the fictional Martha and Ezra, the wait for replies, if they came at all, could be agonizingly long. Ironically letter writing often added to the stress and strain of being apart. Recipients opened letters with a combination of joyful expectation and dread. Good news and glad tidings would raise one’s spirits and increase homesickness. Bad news, in contrast, not only pierced the heart, but it also caused the readers great frustration because they were not able to lend a hand, offer comforting words, or mourn, as the case may be.

If we are to judge from the lyrics of “The Nantucket Girls Song,” written in 1855, perhaps being a whaling wife was not all that bad:

I have made up my mind now to be a sailor’s wife,

To have a purse full of money and a very easy life,

For a clever sailor Husband, is so seldom at his home,

That his Wife can spend the dollars, with a will thats all her own,

Then I’ll haste to wed a sailor, and send him off to sea,

For a life of independence, is the pleasant life for me.

…when he says; Good bye my love, I’m off across the sea

First I cry for his departure; Then I laugh because I’m free,…

For he’s a loveing Husband, though he leads a roving life

And well I know how good it is, to be a Sailor’s wife.105

These lyrics, however, cannot be taken at face value, for they were written, as historian Lisa Norling points out, somewhat tongue-in-cheek.106 Few if any whaling wives viewed separation from their husbands as a blank check to freedom and good times. Instead, they were almost always quite pained at the prospect and the reality of being apart. One wife wrote to her absent husband that she was “very lonesome,” and wondered if there might not be another way to live their lives. “Why should so much of our time be spent apart, why do we refuse the happiness that is within our reach? Is the acquisition of wealth an adequate compensation for the tedious hours of absence? To me it is not…. Thy absence grows more unsupportable than it used to be. I want for nothing but your company.107

It was not only the women who missed their men. In March 1860 Charles Pierce wrote to his wife, Eliza, “It is a dreadful thing for a man to be away from his wife for four long years, not knowing how she is.”108 It was because of such feelings that during the golden age an increasing number of whaling wives and husbands abandoned the married-but-apart arrangement, which had become the leitmotif for the whaling life. Whaling wives became “sister sailors,” following their men to sea come hell or high water (at least one of which was usually guaranteed).109 This privilege—if one were so bold as to call it that—of joining one’s husband on board a whaleship was not afforded to all whaling wives but rather was exclusively reserved for captains’ wives; due to rank, social status, and the fact that the captain’s quarters were the only ones large enough to accommodate roommates of the opposite sex.

In her book Petticoat Whalers maritime historian and novelist Joan Druett documents the trials, tribulations, and joys of many of these resourceful, willful, and devoted women who lived on whaleships alongside their men. She points out that this form of oceangoing cohabitation—like the very notion of a woman living on a whaleship and, heaven forbid, participating in some of the routines of whaling life—was frowned upon when it first came into vogue in the 1820s, being perceived as most “unladylike.”110 A woman’s place was in the home, society proclaimed, and that’s where she should stay. One of the most compelling stories from those early years is provided by the indefatigable Abby Jane Morrell, of Stonington, Connecticut, who simply wouldn’t take no for an answer.

When Abby’s husband, Benjamin, was preparing to go to sea in 1829, she implored him to take her too, regardless of the hardships that the voyage would entail, because she would not “survive another separation.” She swore that she was “willing to endure any privation—let my fare be that of the meanest creature on board, and I shall be happy, if I can see you in health and safety…. I would a thousand times rather share a watery grave with you, than to survive alone, deprived of my only friend and protector against the wrongs and insults of an unfeeling world.”111

Benjamin worried about what the owners might say, and in particular that they would fear that he “would neglect his nautical duties,” and focus more attention on Abby’s needs than the ship’s. Most of all Benjamin worried that bringing her along might lead “slanderous tongues” to damage his “professional character” and subsequent career. But nothing could dissuade Abby—not her husband’s objections or her family’s pleadings that she remain behind. And Benjamin, unable to withstand his wife’s emotional assault or effectively to counter her assertions that all the obstacles he pointed out could be overcome, finally relented, and two days before the voyage was to leave, he said yes, whereupon Abby “threw herself upon my bosom,” he later recalled, “and for some moments could only thank me with her tears.”112

Over time these whaling wives, who often had children in tow, became less of a novelty and more of an accepted fact on board many whaleships, and by the middle of the nineteenth century it was not unusual to encounter so-called hen-frigates at sea. In 1858 the Honolulu-based Reverend Samuel C. Damon remarked, “A few years ago it was exceedingly rare for a Whaling Captain to be accompanied by his wife and children, but it is now very common.” He added that there were at least forty-two such whaleships in the Pacific, and half of them were “now in Honolulu. The happy influence of this goodly number of ladies is apparent to the most careless observer.”113 Although whaling wives did not participate in the daily activities of shipboard life as they related to whaling, they did not have it easy. Just like the men on the ship they confronted nasty weather, worried when the whaling was poor, and had to deal with boredom and loneliness. “How would you feel,” a whaling wife asked in a letter to her cousin, “to live more than seven months and not see a female face?…I spend a great many hours in this little cabin alone during the whaling season, and if I were not fond of reading and sewing, I should be very lonely.”114 However, these wives also had a rare opportunity to escape the boundaries of domesticity and see the world and their husbands in a new light. “We are…in a little kingdom of our own,” wrote Mary Chipman Lawrence while on board the whaleship Addison, out of New Bedford, “of which Samuel is the ruler. I should never have known what a great man he was if I had not accompanied him.”115

Many crews welcomed or at least tolerated having the captain’s wife on board. These women sometimes cared for the men when they were sick and, just as important, gave them a glimpse of home, which could have a healing effect on a weary, weatherbeaten soul. And the children, with their antics and questions, provided a pleasant respite from the monotonous routine of shipboard life. But the captain’s family, in particular the wife, was not always viewed as an asset to the voyage. Some crewmen believed that having a woman on board was bad luck, while others were frustrated that the captain had a woman to sleep with and they didn’t. And more than a few disgruntled crewman saw the captain’s wife as unwanted competition for a limited supply of food.