Chapter Fourteen

“AN ENORMOUS, FILTHY HUMBUG”

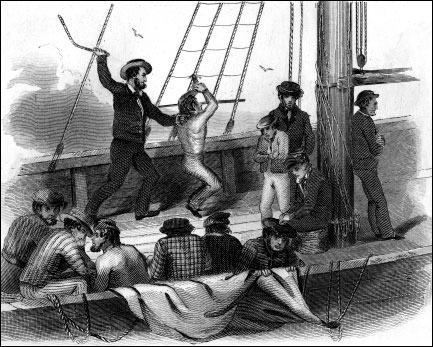

A PICTURE FOR PHILANTHROPISTS, THIS NINETEENTH-CENTURY PRINT SHOWS THE HORRIFIC AND INCREDIBLY PAINFUL PUNISHMENT OF BEING WHIPPED WITH THE CAT-O’-NINE-TAILS, WHICH LEFT THE RECIPIENT BLOODY BUT NOT ALWAYS BOWED.

DURING THE GOLDEN AGE TWO IMAGES OF THE WHALING LIFE competed with each other. There were those who saw it as an exciting and even romantic enterprise, most often because they were considering it from the safety of their own homes and had neither experienced the rigors of whaling, nor knew anyone who had. Then there were others who had a decidedly darker image of the profession. The author of the following passage, written in 1835, clearly falls into the first camp. “’Tis high time you were aware that few voyages…can boast of greater attractions than a ‘whaling cruise’ offers to the nautical lounger, the novelty-monger, the devotee of exciting sports—the anything, or anybody, in short, who, like the Venetian Doges of yore, is in any degree ‘wedded to the imperial sea.’”1 Another contemporary writer saw whaling as a noble pursuit that could help men throw off the oppressive shackles of modern life, which forced them to earn their keep in menial jobs, and instead reinvigorate their character, satisfy their wild side, “gather wealth in the face of danger, and snatch subsistence from the impending jaws of death.”2

The contrasting view, offered primarily by ex-whalemen, and in particular those who labored before the mast, painted whaling in far less glowing terms. To them whaling was a mean and singularly unprofitable line of work. After reflecting on four years at sea, whaleman William B. Whitecar, Jr., politely concluded “by advising all young men who can gain a livelihood ashore, to stay at home.” Ben-Ezra Stiles Ely wrote to assure those who were contemplating a whaling cruise, “that a life on the ocean wave is generally one of many hardships, and of few bright prospects. It demoralizes most persons who devote themselves to it; and raises but a few to nautical eminence, honour and wealth. Generally they who live on the sea have but a short life; and nine hundred and ninety-nine out of a thousand of them are but poor Jack Tars at last.” Charles Nordhoff was a little less genteel, stating succinctly that whaling was “an enormous, filthy humbug.” And George Whitefield Bronson offered a particularly harsh assessment, observing that “whalemen, as a class, have been too long neglected. Too many ships that float are in reality prison-ships;—their crews-for the time being-perfect slaves. White slavery exists this side of Algiers. There are Legrees in spirit—and as far as power extends, in practice—north of the sugar fields of Louisiana. Uncle Tom has many nephews on the sea. We hope some gifted mind will soon faithfully and fully exhibit the interior of ‘jack’s’ cabin.”3

To determine which view is closer to the truth, one cannot simply split the difference. While whaling did have its thrilling moments, these were overshadowed by the inescapable fact that whaling was, during most of the golden age, a miserable pursuit, and the average whaleman’s lot was depressing.

THE GREEN HAND’S TRIALS began as soon as his ship left port. The rocking motion, the salt air, and the uneasiness or outright fear of what was to come usually had him doubled over in fits of nausea and vomiting. Having left behind everything he knew on land, the green hand inevitably cursed his decision to become a whaleman and fervently wished that he could turn back time. One such green hand was nineteen-year old Robert Weir, who had dishonored his family by ruinous gambling and chose to punish himself by going on a whaling cruise. Leaving his hometown of Cold Spring, New York, for Mattapoisett, Massachusetts, Weir joined the crew of the Clara Bell, which left for a voyage to the Atlantic and Indian Oceans on August 20, 1855. His early journal entries are punctuated by the pain of a young man who clearly knows he has made a major mistake. On the second day out he was already bemoaning his situation. “Beginning to get seasick and disgusted…. We have to work like horses and live like pigs.” The next day, while on watch, he saw large sharks circling the ship, and was “tempted” to throw himself “to them for food.” And less than a week after he had lost sight of his “sweet Ameriky,” Weir wrote that he was “absolutely sick and disgusted with living & everything.”4

Regardless of his emotional or physical state, the green hand had to work, and if he didn’t it was certain that one of the mates, with a barked order or a threat of more severe punishment, would quickly see to it that he was performing his duties, such as climbing high into the rigging and setting the sails, a task that was scary enough during the day but truly harrowing at night. In the weeks and months to come, the green hand would go through a trial of fire, as he tried to become a competent if not a respected seaman.

One of the most daunting tasks was becoming fluent in the language of the sea. Every part of the ship had a name. The green hand not only had to know where to find the bowsprit, the jib boom, the cat-heads, the lower deadeyes, the fore-topgallant mast, the spanker, the booby hatch, the lashing rail, the hawsepipe, and the mizzen yard, but also what they were for. Every one of the ropes in the rigging, which at first glance must have looked like a distressed spiderweb, had a name and a function, which had to be memorized, as did all the many sails the ship carried. The green hand also had to understand the language of command, so that when the officers issued orders, he could jump to. All this was difficult enough for native English speakers, but must have been abject hell for foreigners.

Even the rawest of recruits knew that the captain was in charge, but it wasn’t until the captain called all the men forward to give his introductory speech, usually the first full day out, that the green hand realized the extent to which that was so. Every captain had his own style of delivery, but all of them had basically the same message, which was, I am the ultimate authority on this ship, and what I say goes. I will be fair, but any insubordination, any talking back, any failure to execute an order given by me or the other officers, will be met with immediate punishment. There will be no fighting or loafing. If you see a whale, sing out. It is our job to fill this ship with oil and return to port as soon as possible, and I expect that that is exactly what we will do. While most captains’ speeches were extemporaneous affairs, a few captains, such as Edward S. Davoll, wrote theirs down and read it to his crew. Davoll’s speech followed the basic plotline, but some of his specific directions to the foremast hands bear repeating. There was to be:

No loud and noisy conversation…from sunrise til dark [to avoid scaring whales]. No singing or whistling…. No sneaking into the forecastle under the pretense of getting something when it is your watch on deck, because I know all about those things. [And] No sleeping in your watches…. If white water, sing out ‘There She White Waters!’…if a spout, ‘There She Blows!’…if flukes sing out ‘There Goes Flukes!’…Always sing out at the top of your voices. There is music in it.

Davoll knew that the business of whaling often led to complaints, so he warned the crew, “Don’t let yourselves be heard to grumble in any way. I and the officers can do all that. Grumblers and growlers won’t go unpunished.” Davoll had separate speeches for the steward, the cooks, the boatsteerers, and the officers. He took particular pains to clarify the boatsteerers’ allegiance, for these men, although they lived and worked aft of the foremast, were only just above the foremast hands in terms of rank, and the captain wanted to know where they stood in the event of trouble. “If you want to be respected by me,” Davoll told the boatsteerers, “you do as I tell you. But in case you don’t, you cannot inhabit the cabin. All who live aft I count on as my helpers, or officers. And now if you are not for me, say so, for if you are not for me you are certainly against me…. There is no such thing as hanging astride. Either keep aft or keep forward. Decide now and I shall know what ground I stand on.” And to his officers Davoll counseled, “I do not want you should be tyrants and brutally treat men, but I do want you should make them know that what you say you mean, and mean what you say.”5

A common saying among American whaling captains was, “This side of land [by which he meant Cape Horn] I have my owners and God Almighty. On the other side of land, I am God Almighty.”6 A whaleship truly was a “monarchy in miniature,” in which the captain, often called the “old man,” was king, and his officers were the generals.7 For the most part, captains were reasonably benevolent despots, treating their men firmly but fairly, but there were also more than a few who were foul-mouthed, spiteful brutes who relied on intimidation rather than leadership to run their ships. While a captain’s speech might have sounded harsh, especially to those who hadn’t heard one before, that’s how it had to be. Without rigid discipline the voyage would at best founder, and at worst descend into anarchy. The captain’s most important ally in maintaining discipline was his own bearing and rank. If the men respected him, there would be scant possibility of trouble. However, if such respect wasn’t forthcoming, or discipline broke down for some other reason, the captain possessed further tools to maintain order. The means of punishment ranged from a tonguelashing to extra duties to, in the extreme, being shackled, strung up by one’s thumbs, or flogged. The last of these was feared the most. The cat-o’-nine-tails was nine strips of rope or leather with knots along their length, attached to a handle, which could quickly turn a man’s back into a pulpy mass of bloodied flesh. Flogging on merchant ships was outlawed by the U.S. government in 1850, but before that time and after, it was employed by a relatively small number of whaling captains who believed that the cat was the ultimate means of keeping men in line.8

To those who felt that captains were too severe in their actions, a justification was invariably offered that the disputatious behavior of the wayward hands left the captains with no other recourse. To deal with the scurrilous behavior of these men, especially the green hands who often lacked an inherent respect for rank and discipline, captains, it was said, had to act and act quickly.9 Nevertheless, there was a line between discipline and mistreatment, and some captains stepped over it. Such was the case with Benjamin Cushman, captain of the Arab, a Fairhaven whaleship that voyaged to the Indian Ocean in the late 1830s. On multiple occasions Cushman punished the steward, Michael Ryan, for supplying crew members with liquor, a substance that was prohibited on board. In one instance Cushman punched and kicked Ryan repeatedly, drawing blood, and thrashed him with a rope. Another time Cushman punched Ryan and then had him seized up in the rigging, stripped of his pants, and flogged fifteen times across his bare bottom and arms and legs, which not only inflicted hideous lacerations but also caused Ryan involuntarily to defecate on the deck. Not done yet, Cushman ordered Ryan to clean up his own waste with a shovel, and when the dazed and bleeding steward failed to do so quickly enough, he was flogged a second time, and then forced to stand naked at the masthead for two hours in a drizzling rain. On hearing this case on appeal, the Massachusetts Circuit Court upheld the lower court’s ruling awarding Ryan $150 in damages, finding that “the punishment was…excessive in kind and degree,” and “disproportionate to the offense.” The judge added that “there was a gross indecency and impropriety in the character of the punishment, and in the mode of inflicting it.”10

Beyond punishment, there were plenty of other potential discomforts on board, with accommodations ranking high on the list. The captain, of course, had the best lodgings, but they were hardly what one would consider elegant or spacious, and things quickly deteriorated from there, with the bunks becoming more cramped until one reached the worst accommodations on the ship, the forecastle, which seems almost universally to have earned the enmity of anyone who had ever had to dwell there. The best forecastles were bad, while the worst were truly vile. As many as twenty-five men had to fit into this cramped area, with low ceilings, no privacy, little or no natural light, and the grimy patina of whale oil coating everything. There they slept on uncomfortable straw or corn-husk-filled mattresses referred to as a “donkey’s breakfast.”11 Worst was when the heat from the tryworks sent the rats and cockroaches scurrying toward the bow of the ship, where they would march, like armies from hell, over the fitfully sleeping men. One whaleman described the forecastle on his ship as “black and slimy with filth, very small, and as hot as an oven. It was filled with a compound of foul air, smoke, sea-chests, soapkegs, greasy pans, tainted meat, Portuguese ruffians, and sea-sick Americans.” Later, he added, “It would seem like an exaggeration to say, that I have seen in Kentucky pig-sties not half so filthy, and in every respect preferable to this miserable hole; such, however, is the fact.”12

The hierarchy of the ship was also reflected in the food. The captains and the officers, who were fed first, always got the best food and largest servings, while the quality and quantity diminished considerably as one moved on down the line. Shipboard food was designed for longevity, not for taste, and it was not particularly varied.13 One captain told his new hands, only partly in jest, that the shipboard fare would consist of “beef and bread one day, and bread and beef the next for a change.”14 The food came in such predictable waves of the usual suspects that whalemen often could tell the day of the week by what was on the menu. There was salt horse, which was rarely horse and usually beef or pork salted for preservation to such an excruciating degree that if one soaked it in ocean water, the meat actually became less salty and more edible. Biscuits called hardtack were another staple; they were in fact hard as a rock, and any man who bit into one once never did so again. The only way to eat hardtack was either to shatter it and suck on one of the pieces, or immerse it in water or stew to soften it. The whalemen could also depend on getting rice, beans, potatoes, dried vegetables, water, and coffee, perhaps with a bit of molasses added for taste. There also were occasional “treats,” often served on Sundays, such as lobscouse and duff; the former being a mixture of chopped meat, vegetables, and biscuits boiled with grease and spices, while the latter was a pudding of flour, lard, and yeast mixed with equal parts fresh and salt water.15 For foremast hands mealtime was not meant to be an enjoyable occasion. The food was thrown into a wooden bucket, called a kid, and brought forward, whereupon the men attacked it on a first-come, first-served basis.

At the outset of the voyage the food, although not exactly inspired, was at least relatively fresh. As the weeks and months passed, however, the food began to spoil and the water became foul, a transition that was accelerated in hot climates. Everything, even the seemingly indestructible hardtack, became riddled with maggots and overrun by cockroaches, all the while smelling like something that had begun to decay. The cooks made matters worse because often they were cooks in name only, and the results of their culinary adventures were not pretty to see or taste. Nordhoff noted that while the cook on his ship was a very respectable man, who kept his cooking stove exceptionally clean and shiny, he had not the least idea of how to perform his job. He was, said Nordhoff, simply an “abominable” cook. “His bean soup was an abortion—his rice, a tasteless jelly, and the duff—that potent breeder of heart-burns, indigestion, and dyspepsia, even in the iron bound stomach of a sailor—reached under his hands the acme of indigestibility.”16

The whalemen’s diets were greatly enhanced by the occasional catching of fish and periodic infusions of fresh meat and vegetables obtained during layovers. But the amount of fresh food brought on board varied considerably depending on the conscientiousness of the captain and the availability of friendly ports. Whalemen’s journals are full of lively condemnations of shipboard cuisine. “Our duff this noon,” wrote one whaleman, “heavy & watery was literally filled with dirt & cockroaches.” Another found the meat “disgusting,” the molasses to be no better than “tar,” and the food in general to be not even good enough for “a swill pail.”17 And yet another complained that “our beef and pork in general would produce a stench from the stem to the stern of the vessel, whenever a barrel was opened.”18 The only thing worse than wretched food was not having enough to eat. More than a few captains, either following orders from frugal owners or deciding that the only way to cut costs was to cut rations, would serve their men such paltry fare as to skirt the edges of starvation. Whalemen were at least partially able to deaden their hunger pangs through the liberal use of tobacco. Morning, noon, and night, whalemen either lit up or chewed this addictive plant. According to one estimate, in 1844 nearly eighteen thousand American whalemen consumed just over half a million pounds of tobacco, which translates into a usage rate of almost thirty pounds per man.19

WHALEMEN ALSO HAD TO confront the ever-present possibility of getting sick or injured. The predominant malady was scurvy, a vitamin C deficiency caused by a lack of fresh vegetables and fruit. It led to sore gums, bleeding, extreme fatigue, and, if allowed to persist too long, death. Tropical fevers, dysentery, venereal disease, rheumatism, tetanus, tuberculosis, pneumonia, and run-of-the-mill colds invariably made appearances on board ship, as did depression, although not recognized as an illness at the time, which sometimes escalated to suicide, such as was the case for Capt. Thomas B. Peabody of the New Bedford whaleship Morea. At sea on June 3, 1854, Peabody asked some of his officers “if they thought a man would be punished in the other world for making away with himself if he had nothing to hope for or could see no prospect for happiness before him.” The first mate, worried about the captain’s mental state, kept an eye on him and noted that the next day he “seemed melancholy.” In the late morning Peabody called the first mate into his cabin and told him “that he was going to meet his goal.” Alarmed, the first mate called the two other officers to the captain’s cabin, whereupon the officers asked Peabody if he had taken anything. Just “a spoonful of brandy,” Peabody replied. Then, after thinking for a moment, he said that “he could not go with a lie for he had taken laudanum.” The officers were gravely concerned, “but,” as one of the wrote later, “we thought he had not taken enough to cause death [so] we let him bee.” And indeed, the next day the captain appeared as usual on deck. But, the day after, while his men were preparing to chase a whale, they “heard the report of a gun and a musket ball came up through the deck.” The officers rushed to Peabody’s cabin and found him on the deck, “with his face blown off from his chin to his eyes…he breathed a few moments and was gone.”20

In the annals of whaling one would be hard pressed to find a whale-ship cursed more by illness and injury than the Franklin, which left Nantucket on June 27, 1831. From beginning to end, its Pacific voyage was a series of misfortunes so numerous as almost to defy belief. In 1831, for example, one man died of consumption, and two men fell from aloft, with one breaking both legs and the other receiving internal injuries that put him out of commission for two months. In 1832 the pace of calamity accelerated. Another man fell from aloft and died, three men got entangled in harpoon lines and were dragged under to their death, and another man caught malaria.21 In 1833 a man who had strained himself earlier while carrying Galápagos tortoises back to ship died from those injuries, while five other men died from scurvy, including the captain. On July 3, 1833, the Franklin anchored in Maldonado harbor, at the mouth of the La Plata River, in Argentina. The remnants of the crew were so weak that they could not furl their sails, and that task was performed by some kindly French sailors. The same Frenchmen helped the Franklin travel north, to Montevideo, in Uruguay, where new crew members were signed. On August 12 the slightly rejuvenated crew of the Franklin departed for what they sincerely hoped would be the final leg of their journey home. But two months later the Franklin grounded on a reef off Brazil. Although the men and one-third of the cargo were saved, the ship broke apart within ten days, mercifully bringing a halt to the Franklin’s run of calamity.22

Sick or injured whalemen, however, were not left to their own devices. By law each whaleship had to have a medicine chest, and the captain served as the resident doctor.23 The medicine chest came with a list of instructions, informing the captain which substances were to be used to treat various maladies; for example, castor oil for dysentery and cholic, opiates for pain and irritable bowel, and calomel for syphilis.24

Some captains ignored the medicine chest and instead relied on their own time-tested remedies. In this manner ocean sunfish oil was used to treat rheumatism, burying a man in the sand up to his neck for a couple of days or slathering his body with warm whale meat was seen as an antidote for scurvy, and Glauber’s salts, which were used for horses on land, were believed by some “old school” practitioners to be the cure for just about anything.25 When a man feigned illness to get out of work, a smart captain had a quick and effective response. One that was advocated by a Nantucket captain was to cut up a head of tobacco, soak it in blackfish oil, and administer it in the form of an enema, a treatment that was sure, swore the captain, to cure the patient!26

The biggest test for the doctor-captain was the massive injury that demanded surgery. It took a tremendous amount of fortitude for a captain to cut into and try to repair one of his crew, and those are exactly the traits that Jim Hunting possessed. The captain of a Sag Harbor whaleship, Hunting was a giant of a man who stood six feet six and weighed 250 pounds, measurements even more remarkable in the nineteenth century. When one of his men got entangled in a line and was violently pulled from a whaleboat, having four of his fingers ripped from one hand and one foot nearly severed at the ankle, Hunting didn’t flinch. While other men fainted, Hunting strapped the injured man to a plank and used his carving knife, a carpenter’s saw, and a fishhook to amputate the foot and dress the mangled hand. This stabilized the patient long enough for the ship to make it to the Hawaiian Islands, where he was hospitalized.27

Some whaling captains were better prepared than Hunting, and had onboard surgical instruments that were provided with the medicine chest. Still, there was a big difference between having the instruments and having the will to use them. In many cases, rather than perform surgery, with or without surgical instruments, captains hoped that the men could hold on until a port was reached. That is what happened on the Ploughboy out of New Bedford. On March 4, 1849, the Ploughboy was cruising offshore grounds looking for sperms when one of its whaleboats approached a group of seven of them. The boatsteerer threw a couple of harpoons into the biggest one, which thrashed about and then dived. When the whale surfaced, Albert Wood, one of the mates, lanced him several times, whereupon the boatsteerer commented, “We have got an ugly customer.” And so he was. The whale, spouting blood, clamped his jaw onto the boat and, spinning in the water, flipped it over. Wood ended up sitting astride the whale’s jaw, pinned in place. Then the whale smashed his flukes down upon the boatsteerer, killing him instantly, and simultaneously let go of Wood, who grabbed onto the capsized boat. But the whale wasn’t done, striking Wood a few more times with his jaw before backing off long enough for the injured sailor to be hauled aboard a whaleboat that had come to his rescue. Wood’s injuries included a hole in his side, “with fat hanging out,” an inner thigh cut to the bone, and a four-inch gash on his back. On seeing Wood’s wounds, one of the crewmen wrote in his journal, I “am afraid he cannot live. His sufferings are terrible.”28 Wood managed to hang on for thirteen days, until the Ploughboy reached Tahiti, where he was treated by a French surgeon. As for the whale that nearly killed him, it made eighty barrels, and Wood saved one of its teeth as a keepsake.

Although Wood’s encounter with a whale was harrowing to say the least, the chase in most instances provided whalemen with rare moments to experience exhilaration. Walt Whitman tried to capture this feeling in his poem, Song of Joys:

O the whaleman’s joys! O I cruise my old cruise again!

I feel the ship’s motion under me, I feel the Atlantic breezes fanning me,

I hear the cry again sent down from the mast-head, There—she blows!

Again I spring up the rigging to look with the rest—we descend, wild with excitement,

I leap in the lower’d boat, we row toward our prey where he lies,

We approach stealthy and silent, I see the mountainous mass, lethargic, basking,

I see the harpooneer standing up, I see the weapon dart from his vigorous arm;…29

Another writer contended that, “If we regard whaling merely as a manly hunt or chase, quite apart from its commercial aspects, we think it is far more exciting, and requires more nerve and more practiced skill, and calls into exertion more energy, more endurance, more stout-heartedness, than the capture of any other creature—not even excepting the lion, tiger, or elephant.”30 And when nineteenth-century journalist J. Ross Browne sailed aboard a whaleship in the early 1840s, he penned a stirring description of the chase. “Down went the boats with a splash. Each boat’s crew sprang over the rail, and in an instant the larboard, starboard, and waist boats were manned,” and they were off, with the oarsmen leaning into their work to gain the bragging rights of being the first whaleboat to strike a whale. “‘Give way, my lads, give way!’” yelled the boatheader, “‘A long, steady stroke! That’s the way to tell it!’…‘Pull! pull like vengeance!’ echoed the crew,” as they “danced over the waves, scarcely seeming to touch them.” More than two miles from the mother ship, the first whaleboat came within a quarter mile of a large bull sperm whale, and the boatheader redoubled his encouragements. “‘On with the beef, chummies! Smash every oar! double ’em up, or break ’em! Every devil’s imp of you, pull! No talking; lay back to it; now or never!’” But then the whale dived, surfacing nearly a mile off, and began swimming rapidly to windward. Despite the apparent hopelessness of the chase, the men “braced” themselves “for a grand and final effort.” Battling nearly gale-force winds and choppy seas, the whaleboat maneuvered alongside the whale, and the boatsteerer “let fly the harpoon, and buried the iron.” The whaleboat backed off as the whale thrashed its “tremendous flukes high in the air,” showering the men “with a cloud of spray,” and then disappeared beneath the waves. When the whale came up again, the men “dispatch[ed] him with lances.” Weary from the chase, the victors laid upon their oars “a moment to witness [the whale’s]…last throes, and, when he had turned his head toward the sun, a loud, simultaneous cheer burst from every lip.”31

The only element missing from Browne’s rendition is fear. A whalemen who claimed not to be afraid of battling against a sperm whale, or any whale for that matter, was either a damned fool or a liar. To row after a massive animal at least twice as long as your whaleboat, and then harpoon this animal, all the while knowing it could smash your boat or drag it under, was not something to be pursued without serious foreboding. Yet the whalemen had a job to do, and fear often acted as a catalyst. In fact the dangers of the chase were, as one whaleman said, “welcome visitors” because they provided a change of pace from the typical “wearisome” time at sea.32

The sense of achievement that whalemen felt at the end of a successful chase quickly disappeared. Then came the row back to the ship, and then the cutting in, described by one whaleman as “surgery, or dissection, on a gigantic scale.”33 First the whale was brought snug up to the starboard side of the ship, its tail facing forward and the head aft and secured in place by a sturdy chain looped around the flukes. A section of the bulwarks at the gangway was pulled away and the cutting stage—a wooden scaffolding comprising three narrow planks—was lowered over the carcass. The captain and the first and second mates walked out ten feet along either of the stage’s perpendicular planks to the third plank, which connected the first two and provided a platform, replete with a handrail, on which they stood while cutting into the whale below. Armed with razor-sharp, steel-headed cutting spades mounted on sixteen-foot poles, the men began their operation. Typically the captain and the first mate separated the head from the body and secured it to the stern with a chain, to be dealt with later, while the second mate focused on stripping the blubber off of the whale. The second mate began his work by making a circular incision between the eye and the pectoral fin, into which was inserted a one-hundred-pound iron blubber hook that was attached by a chain to a block-and-tackle assembly on board. To get the hook into place, one of the boatsteerers, tethered about the waist to a man on board by the aptly named monkey rope, was slowly lowered onto the whale. This was not a job for the fainthearted. One errant swing of the blubber hook could fracture bones or kill a man, and maintaining one’s footing on the wet, oily, and bloody carcass of a whale was difficult enough in calm weather and nigh impossible when the seas were up. Were the boatsteerer to slip and fall between the whale and the ship, and not be yanked clear by a tug on the monkey rope, he could be crushed against the hull; and if he fell into the water on the other side of the whale he would have to contend with the sharks, or sea wolves as they were called, that were gorging themselves on chunks of blubber.34

With the blubber hook inserted, the peeling commenced. As the men put their backs into turning the windlass, the block-and-tackle hanging from the mainmast creaked under the weight of the massive blanket of blubber that was slowly pulled and cut away from the whale. The cutting trajectory was always at an angle, “like the thread of a screw,” so that the blubber could be stripped in one continuous ribbon, from head to tail, much in the manner that one would strip an entire apple without removing the blade from the fruit.35 Slowly the four-to six-foot-wide strip of blubber ascended higher, as the whale, unraveling, rolled in the water. When the blubber rose twenty to thirty feet above the deck, the boatsteerer, two-foot boarding knife in hand, stepped up to the mountain of flesh and cut a hole in the center of the blanket strip, into which another massive hook and line was inserted, which would soon take up the task of peeling the next slab of blubber from the whale. On hearing the captain cry, “Board the blanket piece!” the boatsteerer stepped forward again, slicing the blubber just above the hole and severing the strip in two, sending the pendulous blanket piece careening across the deck, scattering the men out of the way lest they be knocked senseless or pitched overboard by the swaying mass.36

The blanket piece was then lowered through the main hatch to the blubber room, where one man, wielding a long pole with a hook on the end, called a gaff, tried to hold the blanket piece in place, while another man, perched upon the blubber, used a finely honed spade to chop it into “horse pieces” about one foot square. The blubber room was a treacherous place. Despite the gaffman’s Herculean efforts, the massive blanket pieces would slosh across the floor every time the ship rolled, sliding on a slick of oil, blood, water, and dirt. The horse pieces were, in turn, pitched onto the main deck and sent to the “mincing-horse,” where the mincer, using an extremely sharp two-handled knife, cut the blubber into narrow strips, leaving one end of them attached to the whale’s skin. These flayed horse pieces were called books, and the strips of blubber were called “bible leaves” because of their resemblance to the fanned pages of a Bible. Mincing increased the surface area of the blubber and caused it to boil more efficiently once it was tossed, with a blubber fork, into the try-pots. The process of peeling, chopping, and mincing was repeated until the whale had been stripped of all its blubber, at which point what was left of the whale’s carcass was released, making an excellent if not unexpected meal for the circling birds and the denizens of the deep.

Next the men turned their attention to the whale’s head, which had been hanging off the stern and now was pulled up toward the gangway for processing. For baleen whales the head was hauled aboard or taken to the deck piece by piece. The whalebone was cut from the upper jaw, scraped clean, and set aside to dry before being bundled and stowed, while the whale’s enormous, oil-laden tongue and lips were chopped up in preparation for the try-pots. For sperm whales, first the lower jaw was severed and set aside on the deck to rot until the teeth, still embedded in the gums, could be wrenched free from the jawbone and later extracted for use in scrimshawing or for trade. If the rest of the head wasn’t too large, it would be hauled onto the deck so that the loss of the precious spermaceti could be kept to a minimum. If the head was too big for this maneuver, it was pulled as far out of the water as possible and lashed to the side of the ship. To get to the spermaceti the men cut a hole in the whale’s head and began bailing the case. Usually this was accomplished by repeatedly plunging a bucket attached to a pole into the case to ladle out its contents. Sometimes, however, one of the crew would crawl into the case to do the ladling himself, in effect taking a spermaceti bath. Although this might seem to be a particularly gruesome task, whalemen rarely viewed it that way. Spermaceti was an excellent moisturizer, and the warmth of the liquid could be a welcome change from a cold, biting wind. Melville, in relating the experience of squeezing the lumps out of congealed spermaceti back into fluid, waxed poetic about the orgiastic joys of immersing one’s hands in this most unusual substance:

A sweet and unctuous duty! No wonder that in old times this sperm was such a favorite cosmetic. Such a clearer! such a sweetener! such a softener! such a delicious molifier! After having my hands in it for only a few minutes, my fingers felt like eels, and began, as it were, to serpentine and spiralize…. Would that I could keep squeezing that sperm for ever!…In thoughts of the visions of the night, I saw long rows of angels in paradise, each with his hands in a jar of spermaceti.37

With the cutting in completed, the process of trying out began. For a large whale this could require as many as three days of nonstop activity, by multiple shifts of men periodically relieving one another. It was grueling and dirty work that caused one whaleman to call it “hell on a small scale.”38 Other whalemen offered more detailed and emotional descriptions. Browne observed that “a trying-out scene has something peculiarly wild and savage in it; a kind of indescribable uncouthness…. There is a murderous appearance about the blood-stained decks, and the huge masses of flesh and blubber lying here and there, and a ferocity in the looks of the men, heightened by the red, fierce glare of the fires, which inspire in the mind of the novice feelings of mingled disgust and awe…. I know of nothing to which this part of the whaling business can be more appropriately compared than to Dante’s pictures of the infernal regions.”39 William Abbe, who shipped out on the Fairhaven whaleship Atkins Adams in 1858, provided a less ethereal and more pungent view of the proceedings. “To turn out at midnight & put on clothes soaked in oil—to go on deck & work for Eighteen hours among blubber—slipping—& stumbling on the sloppy decks—till you are covered from crown to heel with oil…to dream you are under piles of blubber that are heaping & falling upon you till you wake up with a suffocating sense of fear & agony…to be weary—dirty—oily—sleepy—sick—disgusted with yourself & everybody & everything…to go through such a scene, I confess the very thought turns my stomach.”40

Toward the end of the trying-out process, the men mopped up in an attempt to glean every last bit of profit from the whale. The scraps of blubber and the oil on the deck, which was kept from oozing over the side by plugging the scuppers, was collected and thrown into the try-pots. The blubber encrusted with meat, which had been hewn from the horse pieces and tossed into casks, was brought forward. After days of decomposing these so-called fat-leans were a noisome mess. The men bent into this slurry of putridity, surrounded by the nauseating stench, and pulled out the “the slimy morsels which are not fit for the try kettles.”41 Those morsels were pitched into the sea, while the contents of the casks were fed to the pots. After the last bit of oil was wrung from the whale and placed in casks to cool, the men began cleaning the ship. The tryworks were attacked first, and here the whale gave its last measure of service. The ashes under the try-pots—the charred remains of burnt blubber and skin—contained lye, an excellent cleansing agent, which was mixed with water and used to clean the crew’s grimy clothes, as well as the decks, until they were “white as chalk.”42 Once the oil had sufficiently cooled, the casks were lowered into the hold or the oil was funneled through a canvas or leather hose to the casks below. To keep the casks tight to avoid leakage, the men would douse them with water up to four times a week.

WHALING WAS A PROCESS of punctuated equilibrium, with the frenzied action of the chase, the cutting in, and the trying out being only a small part of the voyage. Given that it could take anywhere from three to five days to catch and process a whale, and that a good trip might kill on the order of twenty to seventy whales, depending on the species, whalemen were left with ample time on their hands over the course of an average four-year cruise. Not all of this in-between time, however, was free time. There were many activities to attend to, including sailing and cleaning the ship, readying the whaleboats, practicing lowering, sharpening lances and knives, looking out for whales, and doing shipboard repairs.

The length of the voyages, the separation from loved ones, the dangers of the profession, and the monotony of shipboard life made all whalemen pray for the return trip home. “God knows I shall be glad when this cruise is ended,” wrote a whaleman in 1844. “I would not suffer again as I have the last 3 months for all the whales on the North West.” The same year another whaleman moaned, “For the last three or four months I have looked for whales hard—pulled hard in the boats, worked hard on board—and have done next to nothing—which is very hard—and now I am very homesick and can’t get home, which is harder yet. Oh! dear—Oh! Dear. Oh! Dear.”43

How soon the men got to return home depended on a multiplicity of factors. Often the trip ended as soon as the hold was full, and the sooner this happened the shorter the voyage. But even a full hold didn’t always mean a ticket home. Captains could offload their cargo at a port near the whaling grounds, and have it shipped back home on another vessel, while they soldiered on. And when the whaling was poor, the captain could decide to prolong the trip rather than return ignominiously with a barren ship to the icy stares of the owners. Whatever the reason, no whalemen wanted to be at sea any longer than absolutely necessary. When Richard Boyenton, for example, learned, on May 29, 1834, that his voyage on the Salem whaleship Bengal was being extended, he vented his anger in his journal. “I have heard today that our capt intends prolonging this voyage 16 months longer if that is the case I hope he will be obliged to drive a Snail through the Dismal swamp in dog dayes with hard peas in his shoes and suck a sponge for nourishment he had ought to have the tooth ache for amusement and a bawling child to rock him to sleepe.”44

Even if a ship returned full, financial happiness was far from assured. Determining the ship’s profits was a complicated bookkeeping exercise that required the owner to take the money earned by the sale of the cargo and subtract from that, among other charges, sales commissions, insurance premiums, and pilotage, wharfage, and shipping fees. Once the profits were known, they were further divided among the owners and the crew, with the former taking upward of 70 percent for themselves. The profits that remained went to the crew. While the lay system continued to give whalemen a direct stake in the success of the voyage, the gulf between the lays of the captains and officers and those of crewmen widenened over time. Thus a captain’s lay of 1/15th or 1/18th in 1800, might, by midcentury, have risen to 1/12th or as high as 1/8th, and an officer’s lay might have gone from 1/27th or 1/37th to 1/25th or 1/20th, while the lays for relatively green foremast hands during the same period could have dropped from 1/75th or 1/100th to 1/175th or 1/200th. The actual fluctuations depended on the ship, but the basic point held true—the men at the top were getting more, and the men at the bottom less.45

The lays, however, hardly determined the whalemen’s earnings. This was merely the base amount from which a whole list of expenses was deducted. The advance received for signing on, which had been accruing interest ever since the ship left port, was subtracted first. Then came the five or ten dollars that the owner took to pay for loading and unloading the ship, along with a smaller fee to stock the medicine chest. Any purchases of clothes or personal items from the ship’s slop chest, which was the equivalent of a floating general store, were added to the tally. This store, however, was quite different from most of those on land, because it had no competition, its patrons a captive market. Loans made by a captain to a crewman in port had to be repaid with often-exorbitant interest rates. There were other costs to consider as well. The often-overpriced outfitters, who sold supplies to whalemen at the beginning of the trip, and the equally rapacious infitters, who supplied the whalemen on their return, had their hands out, as did the boardinghouse keepers. And one could not forget the shipping agents, whose fee for recruiting crewmen was carved from the lay. Whalemen derisively referred to this menagerie of outfitters, infitters, boardinghouse keepers, and agents as “landsharks.”

The net result was that many of the crewmen on whaleships made little if any money, averaging only about twenty cents per day, and a significant number of them returned in debt. “The lowest grade of landlubber could sell his untrained strength,” Hohman observed, “for an amount two to three times as great as that obtained by the occupant of a whaling forecastle.”46 In contrast the captains and the officers fared much better, and according to one economic study, earned considerably more than their counterparts in the merchant marine.47 And despite a high percentage of losing trips, owners profited the most during the golden age, often earning healthy double-digit returns on their investments. The Lagoda compiled a particularly enviable record between 1841 and 1860, earning an average of 98 percent profit on six voyages.48 Even more lucrative was the Envoy’s trip to the northwest coast, which began in 1848. The year before, Capt. W. T. Walker had taken a great chance, purchasing the condemned Envoy for $325, and then investing $8,000 to fit it out for a voyage even though he was unable to persuade any agent to insure the trip. When the Envoy docked in San Francisco in 1851, Walker and his men had earned the right to gloat. In its three years at sea the Envoy had collected 5,300 barrels of whale oil and 43,500 pounds of baleen, which sold for $138,450. Then, as an additional bouns, Walker sold the Envoy for $6,000.49

Captains and officers, finding the work difficult but financially rewarding, and having few more attractive shoreside job possibilities, often became career whalemen. Not all of them, however, were pleased with a system that routinely rewarded owners so handsomely while often leaving those who generated the profits with relatively little to show for their efforts. On this point the perspective offered by a mate on the New Bedford whaleship Kathleen, in the 1850s, is telling.

For the owners at home a few words I will say

We’ll do all the work and they’ll get all the pay

You will say to yourself tis a curious note

But don’t growl for some day you may chance steer a boat

When your fast to a whale running risk of your life

Your shingling his houses and dressing his wife

Your sending his daughter off to the high school

When your up to your middle in grease you great fool.50

As for the rest of the crew, and in particular the foremast hands, few of them were able to joke about their financial situation, as did Boyenton, who, after calculating that he had earned but a paltry six and a quarter cents per day during the first five months of his whaling voyage, mused about the charitable possibilities that this largess might afford. “I have not as yet concluded weather to give this as a donation to the sabath school union or to the education foreign mission or Temperance societies.”51 Rather than humor or resignation, the usual response after finding out that one had spent four years of his life and had little or nothing to show for it was to curse the captain, the officers, the owners, and the industry, and vow never to go whaling again. And indeed, few foremast hands shipped out on a whaleship for a second time, and those who did were usually in debt to the owner, mildly masochistic, unable to find any more satisfying line of work, or all of the above. The hugely discrepant financial rewards between owners, captains, and officers on the one hand and the rest of the crew on the other underscored the fact that whaling reflected class and social status as much as any industry in pre–Gilded Age America.

The miserable conditions on whaleships and the execrably low pay of the average whaleman spawned a new genre in mid-nineteenth-century publishing—the whaling exposé. Former whalemen, benefiting from the democratization of the press, published harsh and often scathing critiques of the whaling life, all of which complained about the conditions on board and the lack of personal profits. The most comprehensive and extreme attack on whaling came from Browne, who hoped, largely in vain as it turned out, that his representation of the horrors of whaling would generate public pressure to reform the whaling industry.52 “While the laudable exertions of philanthropists have effected so much for the happiness of [merchant sailors, Browne observed]…It is a reproach to the American people that, in this age of moral reform, the protecting arm of the law has not reached [out to whalemen]…. History scarcely furnishes a parallel for the deeds of cruelty committed upon them during their long and perilous voyages.”53 Such whaling memoirs anticipated muckraking books like Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle and Ida Tarbell’s The History of the Standard Oil Company by at least half a century, yet they are hardly as well known. They clearly document, perhaps more than any other books of the period, the vast social disparities that would polarize the American work force in the century to come. And they provide a fascinating and historically significant glimpse of how the labor market would come increasingly to exploit the poor and dispossessed.

The sentiments of these whaling memoirs were echoed by many whalemen who, although not published, wrote down what they thought in their journals. Christopher Slocum, a seaman on board the Obed Mitchell out of New Bedford, addressed himself to the men and women who profited most from whaling. “You wealthy and respectable cityzins of New Bedford who have axquired their wealth by the whaleing business and are still endeveriring too augment their wealth by building and fiting more ships are but little awair how much abuse and hardships is suffered by those men who constitute the crews of their ships.”54

Given such conditions it is no surprise that whalemen often literally jumped ship during a voyage. For much of the golden age it was almost unheard of for a whaleship to return to port with the same men it left with. Desertion rates often exceeded 50 percent, and at times the entire crew was replaced a few times over.55 The United States consul in Paita, Peru, claimed that it was the “small pay and bad treatment” that led the many whalemen to become “disgusted, desert, and either from shame or moral corruption never return.”56 And when one combines desertions with discharges of crewman, often for unruly behavior, the turnover rate could skyrocket, as it did on the Montreal, which shipped thirty-nine men and during a five-year cruise racked up thirty desertions and seventy-nine discharges.57

Desertion was a dramatic step, especially when there was no assurance that the deserter’s situation would improve once he left the ship. While many of these men ultimately returned home, sometimes as hands on another whaleship, others either settled where they landed, were killed by hostile natives, or simply disappeared.58 A letter in The Friend in March 1846, told of three deserters from the New London whaleship Morrison who drowned in Gray’s Harbor on the northwest coast while trying to reach the shore in a stolen whaleboat. The letter, which was signed, “A Friend to Whalemen,” and was undoubtedly penned by a whaleship owner or captain, concluded with a stern lesson. “Would that this might serve as a warning to others when tempted to pursue a similar course, that they may avoid a similar fate, and be induced to continue faithfully discharging the duties of their calling however replete it may be with difficulties and trials.”59

Neither this appeal nor any other plea had much, if any, effect. Desertions kept pace with the worsening conditions in the whaling industry. But no matter how bad whaling was, it offered employment and a salary, or least a semblance of it, to a growing number of impoverished men, both Native Americans and immigrants, who began crowding the city, creating desperate and growing pockets of urban poor, and reflecting a profound shift of America from an agrarian to an urban society.