Chapter Sixteen

MUTINIES, MURDERS, MAYHEM, AND MALEVOLENT WHALES

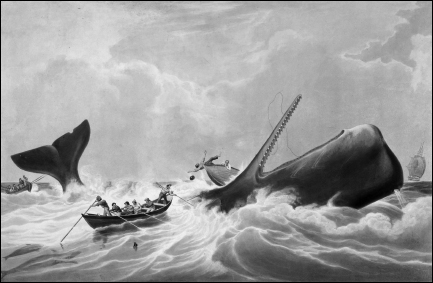

SPERM WHALING IN THE PACIFIC OCEAN. 1834 PRINT BASED ON A PAINTING BY WILLIAM JOHN HUGGINS.

WITH THE LENGTHENING OF VOYAGES, MANY CAPTAINS AND THEIR officers found it difficult to maintain order on board, especially given the degraded character of the crews. In the worst cases, usually when cruel and vindictive officers butted heads with strong-willed and unsavory crewmen, mutinies resulted. Near the end of whaling’s golden age, as the United States marched inexorably toward civil war, these uprisings occurred with surprising regularity and a few became media sensations. Such was the case of the whaleship Junior, which departed from New Bedford on July 21, 1857, bound for the Sea of Okhotsk. The voyage began with high expectations. The Junior had recently returned from a profitable four-year cruise to the North Pacific, and the owners were hoping for a repeat performance.

The owners entrusted the Junior to a callow first-time captain, the twenty-seven-year-old Archibald Mellen, Jr., of Nantucket, a very poor choice indeed. Mellen, who was immediately overwhelmed by his new position, proved to be a woefully lacking leader. Rather than exert his authority, he often wavered in his decision making, projecting weakness to the crew. He made matters worse by turning to his first mate, Nelson Provost, for advice and giving him wide latitude in administering discipline. Provost, a malicious and vindictive officer, looked down on the crew and chose to put them in their place with tonguelashings and repeated corporal abuse. He rarely referred to the men by their names but rather called them “damned Mickey,” “damned Indian,” “black Arab,” or the like, and on one occasion beat a man into unconsciousness with a club, while on another threatened to shoot half the crew before the voyage was over.1

Beyond this litany of abuse, the men had to put up with horrible food. The owners, seeking to economize, had left on board three casks of salt beef that had been on the Junior’s prior cruise. The meat stank and was so rotten than when cooked it simply fell apart, leaving behind a foul slurry that the men could hardly bear to eat. Other provisions, including rock-hard vegetables and wormy bread, were equally inedible. In addition the voyage was, during its first six months, an utter failure. While many whales were seen, not a single one was struck. This dismal record led the officers and the crewmen to accuse one another of incompetence, while the captain drove the men harder and chose to limit their time and freedoms in port. With each passing day the crew became increasingly disgruntled, so much so that all they needed was a spark to set them off, which was provided by a twenty-four-year-old harpooner named Cyrus Plumer.

On his two prior whaling cruises Plumer had distinguished himself not as an experienced whaleman but as an inveterate troublemaker. In December 1854 Plumer had been discharged from the Daniel Wood at Honolulu by “mutual consent,” according to captain Joseph Tallman. Later Tallman remarked that Plumer was “of a very restless, roving and discontented disposition, always wanting to get away from the ship, and a bad and dangerous man to have on ship-board.”2 Then, in 1855, Plumer joined the crew of the New Bedford whaleship Golconda, captained by Philip Howland. The following year Plumer and six others deserted the ship off the coast of Chile. After the deserters left the Golconda, Howland learned that things could have turned out much worse, when one of the boatsteerers said that Plumer had tried to induce him to join in a plot to jettison the captain and take control of the ship. Failing to get enough support, Plumer deserted instead. Given this miserable record, it is a small wonder that Plumer was able to get hired again. That he accomplished this provides yet another example of his duplicity. When Plumer applied for a spot on the Junior, he presented the agent with a beautifully written—and forged—recommendation from Captain Howland. Even if the outfitter had had doubts about the authenticity of the document, he did not have the option of verifying it because Howland was still at sea on the Golconda, which Plumer had seen fit to abandon.3

Given the widespread discontent on the Junior, Plumer had no problem finding other crewmen with whom to conspire, and before long he, William Cartha, Charles Fifield, Charles Stanley, William Herbert, and John Hall were plotting among themselves. Their first impulse was to desert, but when they tried to leave the ship off the Azores, barely six weeks into the voyage, they found their way blocked by the officers, who were ready for such an attempt. Subsequently Plumer convinced his compatriots that mutiny was the only alternative. The plan was to lure the second mate, Nelson Lord, to the main deck to check a damaged sail, whereupon Fifield would knock him unconscious while the other mutineers, hiding in the shadows, would go below to subdue the captain and the other officers. But when Lord fell for the bait, and climbed onto the bowsprit to fix the sail, Fifield lost his nerve. Striking Lord at that point would have sent him plummeting into the ocean, and although Fifield was willing to mutiny, he was not, he later recalled, willing to kill a man.4 This close call caused the mutineers to lose some of their ardor, and for a couple of months they stayed their hands. Then, on Christmas, while spirits sagged and the Junior was sailing in a northeasterly direction five hundred miles off the southeastern tip of Australia, Plumer roused them to action.

Early in the evening Captain Mellen honored the holiday, giving each of the crew a shot of brandy, while he retired to his stateroom. A short while later Lord gave them a bottle of gin as a “treat,” and then he too went below.5 The liquor loosened the men’s tongues, and soon they were complaining bitterly about the voyage, their bad luck, and their treatment at the hands of the officers, in particular Provost. Just after midnight Plumer turned to the small group huddled around the deck pot and barked angrily, “By God, this thing must be done tonight!” When one of the men asked what thing he was talking about, Plumer responded, “We must take the ship.”6 Plumer then passed around a coconut shell full of gin and urged his coconspirators to take a deep draft and prepare for action.

While Fifield and Stanley stood guard on the main deck, Plumer, Cartha, Herbert, Hall, and Cornelius Burns went below and armed themselves with thirty-five-pound whaling guns, boarding knives, cutting spades, and pistols. As the others stood silently outside the officers’ cabins, Plumer crept into the captain’s cabin, leveled the muzzle of a whaling gun, yelled “Fire!” and pulled the trigger.7 Three large balls tore through Mellen’s chest and embedded themselves in the side of the ship.

“My God! What is this?” Mellen yelled as jumped up from his bed. “God damn you, it’s me!,” Plumer screamed, as he grabbed Mellen by the hair, yanked back his head, and began hacking away at him with a hatchet, slicing open his chest and administering a lethal blow that nearly severed his head.8 The firing of the gun woke the men in steerage and the forecastle, but when they came aft to see what was the matter, one of the mutineers shouted, “Go back, or I will cut you down!”9

The violence quickly escalated. Following Plumer’s lead, Hall shot the third mate, Smith, with a whaling gun, then Burns skewered him with a boarding knife to make sure that he was dead. Cartha shot Lord in the chest, and Provost was shot in the shoulder with a whaling gun, the impact of which flung him back into his bed; the shot also ignited the bedding. As smoke filled the lower deck, the mutineers and the others below, including Lord, who had survived his injuries, climbed onto the main deck. When Provost came to moments later, he moved through the smoked-filled cabins, opened the captain’s sea chest, took out his revolver, and loaded it with three shots. Plumer yelled down to Provost to come up. “I shan’t come up there,” Provost replied. “And if any of you shows himself below the hatch he is a dead man. I have a revolver, and I will shoot.”10 Bleeding badly and choking on the smoke, Provost retreated to the lower hold to hide.

The mutineers controlled the ship, and Plumer took command. “I want you all to understand,” he said to the men on the deck, “that I am captain of this ship now. If you behave yourselves and obey orders, you will be well treated; if not, look out for squalls.”11 His first order was to extinguish the fire, and the men responded by dousing it with water. By the time the sun rose on December 26 the fire was out, and Plumer proceeded to consolidate his position. All the men who did not participate in the mutiny were made to hand over their sheath knives and any other potential weapons. These, along with all the harpoons, spades, and knives, were thrown overboard. Now only the six mutineers were armed, and they kept a close watch on the rest of the men. The next step was to dispose of the bodies. Plumer refused to participate, claiming that “he could kill a man, but couldn’t handle the corpse,” and instead he sent three men below for this gruesome task.12

The captain was hauled up first, and his body was weighted with a chain and thrown overboard. “Go down to hell,” yelled Plumer, “and tell the devil I sent you there!”13 The third mate was then brought up and tied to a grindstone before being pitched over the side. A little while later, thinking that Provost might have succumbed to his wounds, Plumer sent Dutch crewman Anton Ludwig below to find the first mate. While Ludwig groped around in the sooty darkness, he bumped into something and yelled, “Another body hard fast to a rope!” Plumer inquired, “Large or small whiskers?” and Ludwig responded, “Small whiskers.” Plumer yelled back for Ludwig to haul up the body, but when he climbed out of the cabin and into the light, the men started laughing and poking “fun at the Dutchman,” because the body that Ludwig had in tow was not Provost’s, but that of the captain’s dog, which had died from smoke inhalation.14

Plumer had been in this part of the world before, and he knew not only of Australia’s vast size but also of its gold mines. If he and the other men could get ashore, Plumer thought that they could disappear and ultimately find their fortune. But first he had to get ashore, and that, he quickly realized, was going to be a real problem. They were five hundred miles from the coast, and none of the mutineers knew how navigate the ship. If they headed in the wrong direction, it could be weeks or months before they hit land. The only navigator on board was Provost, so Plumer demanded that he be found. Repeated searches turned up nothing, leading some of the mutineers to fear that Provost had gone over the side. But then, on the fifth day after the mutiny, Provost’s hiding place was discovered. Unable to stand and teetering on the edge of death, Provost passed up his revolver and was hauled to the main deck. He “presented a shocking and pitiable appearance,” according to one witness, his body caked in dried, blackened blood, his greasy hair standing on end, his eyes sunken into their sockets.15 To gain Provost’s assistance, Plumer promised to spare his life and give him control of the ship as long as he sailed the Junior to Cape Howe so that Plumer and the other mutineers could make their escape. Provost agreed, and by January 4 they were in sight of land.

In preparing to depart the five mutineers, with five other crewmen, some who had been conscripted, loaded two whaleboats with provisions, valuables, and firearms.16 Plumer, knowing that Provost was a religious man, had him swear on a Bible that he would take the Junior to New Zealand, thereby giving the mutineers a head start on their new life. Provost, in turn, concerned that he and the other men left behind might be implicated in the mutiny without evidence to the contrary, asked Plumer to provide written proof of their innocence. Plumer obliged by dictating a confession, which was written into the ship’s log by Herbert, and signed by the mutineers. It surely ranks as one of the most unusual and fascinating documents in all of whaling:

This is to testify that we, Cyrus Plumer, John Hall, Richard Cartha, Cornelius Burns, and William Herbert did on the night of the 25th of December last take the Ship Junior and that all others in the ship are quite innocent of the deed….

We agreed to leave [Provost]…the greater part of the crew and we have put him under oath not to attempt to follow us; but to go straight away and not molest us. We shall watch around here for some time and if he attempts to follow us or stay around here we shall come aboard and sink the ship….17

When the whaleboats departed with the mutineers on January 4, Provost headed the ship on a course towards New Zealand, as he had sworn to do, but as soon as the whaleboats were out of sight, he turned the Junior around and sailed for Sydney. Oath or no oath, Provost didn’t feel bound by promises made to murderers. The Junior arrived in Sydney on January 10, and two days later Provost dictated a letter to the ship’s owners, apprising them of the situation.18

As soon as the Junior sank below the horizon, the mutineers headed for land, only twenty miles away. Plumer’s boat, with four men on board, took the lead, sailing through the rough seas at a good clip, while the six men in the second boat, which was leaking and heavily weighted down with supplies, quickly fell behind. As night approached, Plumer, wanting to keep the group together, waited for the second boat to catch up, and the two boats floated together until dawn on the rough, open ocean. During the night Alonzo D. Sampson, fearing that his second boat would swamp unless lightened, convinced Plumer to allow him to discard all of the items on board, save a “keg of powder and a little hard bread.”19

At first light, the two whaleboats set off again, and soon Plumer’s was way out in front. According to Sampson, this is when he and one of the other men on his boat, Joseph Brooks, neither of whom had participated in the mutiny, decided they didn’t want to continue following Plumer, preferring instead to set out on their own. Before they could make a break for it, however, they had to get the four other men on board, Herbert, Burns, Hall, and Adam Canel, to accept the wisdom of their plan. “We soon convinced them,” Sampson later recalled, “that Plumer had plotted to drown them,” by placing them on the least seaworthy boat, and that their only chance was to get to shore as quickly as possible. And with that agreement, the men on the second boat rowed to shore, landing after a short, drenching, and damaging ride through the churning surf a little to the south of Cape Howe.20

Plumer, who soon realized that he had lost his consort, turned his boat around to see what had happened. When Plumer sighted the six men and their boat pulled up on the shore, he demanded to know what was the matter, and why in the “Devil’s name” they had landed.21 Sampson replied that they did so to avoid sinking, an answer that didn’t sit well with Plumer, who began waving his hands, claiming that if he could get to shore he would “shoot” them. But with the surf even worse than when the men had landed, Plumer decided not to try, and he reluctantly continued sailing until he reached Twofold Bay, some 50 to 75 miles north of where Sampson and the others had come ashore.

On shore Plumer’s hapless group, which included Stanley, Cartha, and Jacob Rike, wandered into a nearby town and tried to pass themselves off as Americans in the middle of a trip from Melbourne to Sydney. “But,” as the Sydney Morning Herald reported, “the singularity of such a voyage being taken in a whaleboat, their arms and the nature and value of the property they had with them, excited suspicions.” The local authorities were suspicious enough to arrest the four, only to release them soon after for lack of evidence. Although they were still not quite sure what to make of this motley band of visitors, the locals let them be for a while, during which time the men settled into a rather comfortable lifestyle, donning fine clothes and spending a considerable amount of money in drinking establishments. Plumer, who referred to himself as Captain Wilson, amused the locals with wild stories of daring on the high seas, and apparently was quite a ladies’ man, with one rumor circulating that he had become engaged to a local girl.22 But when the news of the mutiny reached this outpost, the mutineers were captured in early February and brought to Sydney.

The other six men had an even more interesting fling with freedom. After spending seven days walking under the blazing sun along the endless beach, finding water scarce and food scarcer, they were on the verge of starvation when they saw a man in the distance, at a river’s edge. “Boys,” Sampson shouted, “yonder is an Indian, or something in human shape. Let us go to him. It is the best we can do. Our condition can’t be made any worse than it is already.” When they approached the native, he took fright and ran off, and the men followed, soon coming to a village which lay on the stream’s opposite bank. The natives (Aborigines), who spoke no English, motioned for the men to cross the river, and then sent a canoe to get them. One at a time the men were ferried over, and on landing they were stripped of most of their belongings. “When they had robbed us to their heart’s content,” Sampson said, “they took us before their chief, whom we found in the principal hut, which would have made a tolerable pig-sty in good weather.” Despite being nearly blind, the gray-haired chief inspected the men very closely, looking them up and down and even examining the insides of their mouths, and every once in while saying something that caused peals of laughter to erupt from the other Aborigines. Once the inspection was over, the men were ushered into an empty hut and given fresh fish to eat.

Fearing that the Aborigines were cannibals, the men “stood watches in order to guard against being massacred by stealth,” and looked for an opportunity to escape, which came about a week after they had arrived. As soon as their guards had fallen asleep, the men crawled out of the hut and down to the river. They decided to swim from bank to bank while slowly making their way upstream, hoping that the frequent immersions would throw off any pursuers. After swimming the river twelve times, however, they were too exhausted to continue and headed into the bush.

The next day they came upon another group of natives, one of whom spoke broken English and told them that two white herdsmen lived nearby, and that he would guide the men to the herdsmen in return for a shirt. The deal struck, the men and their guide set out. Within a day they found the two herdsmen, who fed them and told them of another settlement which the men went to next. It was there that the group split up, with Burns and Hall going one way and the other four men—Sampson, Brooks, Herbert, and Canel—going another. The group of four hired themselves out at the end of January 1858, to an Irishman who ran a pub house near Port Albert in southern Victoria. They stayed there about a month and then continued on their way, stopping to hire themselves out again, this time as lumbermen, but before they could settle in to this new job, the law caught up with them. According to Sampson, one day while walking down a dirt road, a couple of policemen on horseback approached the men and inquired what they were about.

“We are going to work for Mr. Smith,” Sampson replied.

“You are, eh?”

“Yes, that is the calculation.”

“What are your names?”

The men told them.

“Did you sail on the ship Junior?”

Inexplicably, they said yes.

“Just the men we want,” and with that the policemen drew their revolvers.

Sampson, laughing nervously, asked them what they planned on doing with their guns, to which the policeman replied, “Nothing, but we are going to put you in irons.”23 Back at the station, the policemen asked where Burns and Hall were, but Sampson and the others told the police they had no idea. Indeed, Burns and Hall were never found or heard from again, causing one to wonder whether they were killed by Aborigines or were assimilated into the local population.24 Soon after their capture Sampson, Brooks, Herbert, and Canel were duly shipped off to Sydney, where they joined Plumer and the others in Darlinghurst jail in early March.25

After a hearing that conferred legal jurisdiction on the American courts, the mutineers were shipped back to New Bedford, ironically aboard none other than the Junior. The American consul in Sydney, understandably eager to avoid escape attempts, had the Junior fitted out with eight specially constructed prison cells, which measured six feet square apiece, had thick wooden bars reinforced with iron, and were bolted to the deck. Provost and Lord had to be sent home on another ship, for the Junior’s crew, or what was left of it, categorically refused to sail with their former officers. The Junior’s return voyage proved uneventful, with one exception. Herbert wrote a note and managed to get it to Plumer through a chink in the cells. Plumer read it, tore off a piece that had his name written on it, and attempted to pass the remaining portion of the note to Richard Cartha, by way of one of the guards. Plumer had hoped that by wrapping the note in a lock of his hair the guard might not take notice, but simply pass it along. The guard, whose curiosity was piqued by this curious package, immediately gave it to Captain Gardner, who upon reading it discovered that the mutineers had hoped to bribe one of the guards into letting them out so that they could attempt to take over the ship. With the plot uncovered, Gardner ordered further reinforcements for Plumer, Herbert, and Cartha’s cells.26

At the New Bedford dock, the manacled mutineers were greeted on their arrival by throngs of curious and angry onlookers, who had been avidly reading about the mutiny for weeks. Thousands of people came to see the Junior and inspect its holding cells, and many made their way to the large window of a local insurance company where daguerreotypes of eight mutineers were displayed. Reflecting on this unfolding spectacle, worthy of a scene in a Dickens novel, the New Bedford Mercury wrote, “No whaler that ever belonged to this port has been an object of so much interest as the Junior.”27 On viewing the daguerreotypes a writer for another local paper quipped, “The prisoners were pronounced on all hands to be a ‘desperate looking set of fellows.’ We don’t think they look half as badly as they acted.”28

The trial, held in U.S. District Court in Boston, lasted three weeks and included passionate speeches from the prosecution and the defense, accusations of guilt from various officers and crew members, proclamations of innocence from the accused, and charges and countercharges about what transpired on the Junior. Papers in Boston, New York, New Bedford, and Nantucket followed the proceedings with a tabloid intensity that was surpassed only by their readers’ appetite for news about the case. On November 9, 1858, the first day of the trial, one of the lawyers for the government stated, “The case to be presented and proved was not one of manslaughter, or any minor degree of crime, but one of downright, absolute murder, and if the government does not prove this in its fullest degree, it will prove nothing.”29 By this measure the government failed. While the jury found Plumer guilty of murder, his three accomplices—Cartha, Herbert, and Stanley—were found guilty of the lesser charge of manslaughter.30 The other four men were not implicated in the murders and were not found guilty of any crimes.

Almost five months later, on April 21, 1859, the mutineers were back in the courtroom for sentencing. The room was filled to capacity, and every available standing place was taken, with the overflow crowd spilling into the entryway. According to one local paper, “Plumer received the announcement of the sentence calmly, but with a sad expression upon his countenance; Cartha manifested extreme indifference; while Herbert and Stanley smiled.”31 Justice Nathan Clifford, one of the two judges who had heard the case, asked Plumer if he had anything to say as to “why the sentence of death should not be pronounced upon him.” Plumer responded, “I have very much to say,” and he asked the clerk to read his written statement to a hushed courtroom.

I object to the sentence of death being passed upon me: 1st because I am not guilty of the death of Captain Archibald Mellen. His blood does not rest on my hands…. the death of Captain Mellen was caused by wounds inflicted with a hatchet in the hands of another person, who went into the Captain’s stateroom, and who afterwards coming on deck, stated to another person that I “missed the captain, but that he did not miss him,” and boastingly showed the blood on his Gurnsey frock, saying “it was the Captain’s blood, and that he was the butcher.”

That man is Charles L. Fifield, whom I generously, but unwisely, screened from suspicion, assuming his crime, that he might remain in the ship, because he came to me in tears and told me he dared not go on shore with the other men with whom he had quarreled, and who abhorred him and his conduct. I have been convicted by the perjury of that man.

Plumer’s statement further maintained that the “real culprit” was none other than one of the officers on the ship, Nelson Provost, “whose contriving and intriguing heart were the instigating cause of the conspiracy and mutiny.” Plumer’s third reason for objecting to the sentence was that he was “guiltless of taking life,” and, in fact, had tried to preserve life by sparing Lord and Provost.

In view of these facts I maintain what I know to by my real character, that I am not the bloodthirsty man that the law would make me out to be, and that the ends of justice and the security of life and property in the commercial marine under similar circumstances, would not be promoted, but jeopardized by passing and executing sentence of death upon me.32

The judges were unmoved by Plumer’s plea, his claim to be “a humble and penitent believer in the Lord Jesus Christ,” as well as the numerous affidavits he laid before the court, attesting to his character and his version of the story. Judge Clifford delivered Plumer’s sentence: “It is considered by the court that you be deemed guilty of felony and that you be taken [back to prison until June 24, 1859, when you will be taken to your place of execution]…and there you be hanged by the neck until you are dead; may God have mercy on your soul.”33

Next Clifford sentenced Plumer’s accomplices to jail time and fines. One of the reporters noted that tears welled up in Plumer’s eyes while listening to the judge’s statement. The New Bedford Mercury, however, had scant sympathy for Plumer’s plight, and ran an editorial that described him as a symbol of abject failure.

Cyrus Plumer’s case reads a sad, impressive and terrible lesson to the youth who embark on our ships and sail to distant seas for a long period of difficult duty. The experience of this man shows the need of full and firm conviction that duty must be done and discipline must be maintained. The constraint of the voyage, the perils, the tedium, and the confinement demand cheerful spirits and repression of all dark and evil thoughts. Cyrus Plumer did not, in the hour of temptation, come up to the required demands.34

The Mercury’s harsh assessment was shared by virtually all of the other papers as well as the people of New Bedford. The more frequent these mutinies became, the greater the threat to the livelihoods of whaleship owners, captains, crews, and those who depended on them, and, therefore, the greater the threat to New Bedford’s economic well-being. Not surprisingly New Bedford’s residents cheered Plumer’s sentence and hoped that it would serve as a warning to those who might contemplate a similar crime.

Ultimately the court of public opinion proved more powerful than the court of law. While Plumer languished in jail and his lawyers sought to overturn his sentence, he actually became an object of compassion and an unlikely cause célèbre, his case taken up by the swelling ranks of Northern evangelicals, many of whom detested capital punishment.35 New witnesses were duly trotted out, whose recollections, it was argued, proved Plumer’s innocence, and new “facts” were uncovered that purportedly did the same.36 Petitions were circulated on Plumer’s behalf, and one such effort generated 21,146 signatures—including Ralph Waldo Emerson’s—mostly from the Boston area, with only a very few from New Bedford.37 Plumer aided his own cause, either out of conviction or calculation, by aligning himself with God and taking baptism in his cell from the prison’s chaplain on the eve of his scheduled rendezvous with the hangman’s noose. Editorialists took sides on the issue of whether Plumer should live or die. The Boston Courier and the Boston Journal sniped at each other in one of the harsher interchanges recorded during this time.

The Boston Courier opined:

The murders of the officers on the whaleship Junior were as atrocious as any we have ever heard of. Does the fact that Plumer saved the lives of two officers blot out the guilt of his taking the lives of Captain Mellen and Mate Smith? We cannot find the shadow of a trace of palliation in this case or this crime and must reserve our sympathies for a better cause. Let others indulge their own.

The Boston Journal, eager to appeal to its own audience of more sympathetic readers, shot back:

The Boston Courier seems to be thirsting for the blood of Cyrus Plumer and descends to the contemptible artifice of sneering at those acting in his behalf…. It appears as though the Courier man would be glad to volunteer to kick the fatal drop from beneath the convict’s feet and hurry him into eternity…. Letthe Courier and its malignant hatred of whatever is generous and human pass. It is hoped that the President will grant Plumer a reprieve.38

President James Buchanan, woefully inept at dealing with the regional divisions that were leading the country toward civil war, found time to focus on the case, and succumbed to the coordinated public campaign on Plumer’s behalf, commuting his sentence to life in prison. In his letter of commutation Buchanan noted that “ten of the jurors who tried the cause have earnestly besought me to commute the punishment,” and that even “the District Attorney who conducted the prosecution against Plumer on the part of the United States, has in an official communication ‘cheerfully’ borne the testimony of his opinion ‘that there are considerations connected with the conduct of Plumer which address themselves to the execution of clemency.’” On learning that his life would be spared, Plumer wrote a note in which he expressed his “thanks to all the friends and editors of public journals who have been active in my behalf—to all the signers of petitions in my favor—to many friends at Washington—to members of the cabinet, and especially to the President of the United States.” He assured them that his “future conduct shall show that interest has not been felt or mercy shown to a bad or unworthy man.”

Not surprisingly Buchanan’s commutation precipitated another heated debate in the press, with observers either applauding or decrying the president’s action. Whaleship owners, in particular, were out-raged that a convicted murderer would be let off, fearing that such a precedent would make subsequent mutinies more likely. “Whaling masters in these days must go well-armed,” wrote the editors of the Whalemen’s Shipping List upon hearing of the commutation, “and, expecting no favors from home, must exercise their judgment for the maintenance of order, the preservation of peace, and protection of life.”39

But that was not the end of the story. Plumer’s lawyer, Benjamin F. Butler, who went on to become a highly controversial general under Ulysses S. Grant, was elected after the war to Congress representing Massachusetts. He had not forgotten about Plumer all those years, and when Grant became president, Butler pleaded his former client’s case to his old commander, aided by testimonials from various Massachusetts politicians and the warden in the prison where Plumer was being held. Grant, in turn, pardoned Plumer—nearly fifteen years after the trial.40

ATTACKS FROM WITHIN WERE not the only ones that whaling captains feared. Hostile natives sometimes posed a serious threat to a whaleship’s command, and a smart captain was always prepared for the worst, especially when sailing near Pacific islands with dangerous reputations. In one instance, on October 5, 1835, the Awashonks, out of Falmouth, Massachusetts, anchored off the island of Namorik (Baring’s Island), in the Pacific Ocean, to get supplies. Shortly before noon, about a dozen natives paddled to the ship in three canoes loaded with coconuts and plantains, unarmed and seemingly intent on bartering with the crew for metal and sperm whale’s teeth. Capt. Prince Coffin, looking upon this as a good opportunity to stock up, let the natives, who were noted to be “well-formed, muscular men,” come aboard.41 Nothing seemed amiss, as additional canoes came from the island, and the number of natives on the ship swelled to a band of almost thirty. A small group of them clustered about the middle of the ship where the harpoons, spades, and lances were stored. Coffin, seeing that the natives were fascinated by the iron and steel instruments, grabbed a spade and wielded it as if cutting into blubber, then put it back on the rack. This display generated quite a bit of animated conversation among the natives. Then the third mate, Silas Jones, called out to Coffin that one of the natives was coming up the gangway with a war club in his hands. Coffin, sensing danger, ordered the first mate immediately to clear the natives from the deck. Jones struggled with the man coming up the gangway, wrenched the war club free, and threw it over the side. But no sooner had he done so than another native, also clutching a war club, tried to get over the railing. As Jones went to deal with that native he heard a commotion behind him, and turned to see that the other natives had rushed forward, snatched the spades, and then turned on the surprised and largely defenseless crew. With a single swipe of a spade, one of the natives cut off Coffin’s head. The second mate and two crewmen jumped overboard where “they were soon destroyed,” while the rest of the crew ran for their lives, with some climbing the rigging and others jumping through the hatch. Within minutes the natives had control of the deserted main deck. Below decks Jones and four other seamen gathered to assess the situation. Lying before them was the first mate, who had been fatally stabbed as he leaped down the hatch-way. “Oh, dear Mr. Jones,” the first mate was reported to have said with his dying breath. “What shall we do? Our captain is killed and the ship is gone!”

Jones and the other men found and loaded a couple of muskets. Meantime the natives had gathered at the head of the gangway, but before they could descend to dispatch the crew, Jones aimed and fired into their midst. “If they had all been struck by lightning from heaven,” Jones later wrote, “they could not have ceased their noise quicker than they did.” The stunned natives began throwing their weapons toward Jones and the other men, who continued firing back. Suddenly the crew was faced with an even greater concern. The natives were attempting to steer the Awashonks toward land. Were they to succeed, the ship would surely founder against the rocks and the remaining crew would have no chance of survival, because instead of dealing with a small band of natives on board they would have to face all the inhabitants of the island. Jones and one other crewman fired their muskets repeatedly through the planking in the vicinity of the helm, and all went quiet. Not knowing what was happening above them, Jones and his men thought that their only chance lay in attacking the natives head-on. As the men made their way up the companionway, they heard the rush of footsteps on the main deck, and before Jones could get his head above the level of the deck, the muzzle of his musket was grabbed. Jones’s momentary shock was immediately replaced with joy. The hand on the muzzle belonged to one of the crewmembers who had earlier climbed aloft, and who now exclaimed, “Oh, Mr. Jones, I did not know you were alive. They are all gone. They are all gone.” When Jones had shot through the planking, he had killed the chief. Their leader lost, the remaining natives jumped over the side and paddled for shore. Fearful of another attack, Mr. Jones, now Captain Jones, and the crew got the ship under way. Six weeks later the Awashonks sailed into Honolulu. The final toll—six dead and seven wounded.42

The Charles W. Morgan had a very different kind of encounter with hostile natives.43 In 1850, Capt. John D. Samson spied a raft of canoes coming from the Central Pacific island of Sydenham and paddling quickly toward the Morgan. He ordered his men to bring up the fire-arms and pull in all the ropes that could be used to climb aboard. Samson would much have preferred simply to sail away, but there was no wind, and the ocean current was bringing the Morgan ever closer to the reef surrounding the island, where the natives appeared to be anything but a welcoming party. As the canoes got closer, Samson moved his men into position along the rails, each one armed with a spade or lance, ready to repel any boarding attempt but not kill the natives if it could be helped.

The first canoes to arrive came right up to the ship, but as the natives tried to grab the hull, the men above swung and jabbed their weapons, causing the attackers “to shove off with shouts of fear and eyes sticking out like crabs’.” For an hour or more, canoes kept arriving until the Morgan was surrounded by “a cluster twice the length of the ship and at least five or six deep.” The five hundred or so natives in this war party were “jabbering and gesticulating with a din and uproar that made things hum.” Their most heated gestures were directed at Samson, who was armed with a musket and walking calmly back and forth on the poop deck, surveying the scene, and giving occasional orders to his men. Despite his apparent nonchalance Samson was increasingly worried. The ship was continuing to drift toward the reef, which was now only three-quarters of a mile off the bow. He and his men knew that if the ship grounded on the reef or managed to clear the reef and grounded near the beach, they would be done for. The option of lowering the whaleboats and using ropes to tow the Morgan clear of these obstacles was foreclosed by the natives, who would certainly kill any whalemen foolish enough to leave the ship.

The natives, apparently concerned that the currents might allow their prize to slip away, rushed at the ship from both sides, whooping and hollering insults, and then retreated at the first sign of resistance. With considerable glee they showed their rumps to the whalemen, a move that finally got the better of Samson, who asked for the shotgun. When a “large dignified-looking chap” repeated this gesture, amplifying the effect by placing one hand on either side of his rear end, Samson hit the “shining mark” with a load of shot, propelling the offending native headlong into the water. This quieted the natives for only a moment, and then they resumed their attacks more furiously than before, this time coming at the ship simultaneously with many canoes from different angles, and trying desperately to grab onto “the chain plates and moldings with their fingers” in order to climb up the sides, “which were bristling with steel fore and aft.” Many of them cut and bloodied, the natives fell back into their canoes. Having failed in so many attempts, they did not attack again but waited to see if the ship would come to them.

The Morgan slowly drifted to the edge of the reef, and the men could clearly see the coral just beneath the surface on both sides of the ship. When the copper-sheathed hull gently grazed a coral head, breaking off some fronds, the natives began jumping up and down and swinging their clubs. As boatsteerer Nelson Cole Haley observed, there was no mistaking this display, it clearly “meant they would soon be beating out our brains.” The Morgan was eerily silent. All the men could do was watch and pray that the ship would skirt the reef. At the same time the nearby beach was lined with natives who were hoping for a very different denouement. After nearly a half hour of mounting tension, the mate gave all on board a fright, calling out that there was “a patch of coral right across our bows just under water,” which the ship would could not clear. The natives, sensing that the final act was near, “began dancing up and down with delight.” But then, slowly, the Morgan’s course shifted. The current gently turned the ship’s bow until it was almost ninety degrees from the collision course it had been on just a few moments before. In ten minutes the Morgan was miraculously well past the reef and in deep water, slowly drifting away from danger. Now it was time for the whalemen to celebrate, firing all their guns and letting out “three cheers” as the severely disappointed natives paddled back to shore.

There are many other stories of bellicose natives attacking whaleships and, in some cases, enslaving and even eating the men they captured. Some of these attacks, like those on the Awashonks and the Morgan, were unprovoked. But it is equally true that in many instances the natives had profound reason to be angry, if not murderous. Some whaling captains were guilty of what was called “paying with the fore-top-sail,” which essentially meant telling the natives that they would be paid for the proffered supplies the following day, then sailing off. Little wonder then that when the next whaling vessel stopped by this island, the chief would believe that white men lacked honor. There was, unfortunately, a good deal of truth to J. Ross Browne’s claim that “there has been more done to destroy the friendly feelings of the inhabitants of the islands of the Indian and Pacific Oceans toward Americans by the meanness and rascality of whaling captains than all the missionaries and embassies from the United States can ever atone for.”44

WHALESHIPS WERE NOT ONLY vulnerable to mutineers and hostile natives but also to whales.45 At about ten o’clock on the evening of September 29, 1807, the Union out of Nantucket was cruising at a good clip off Patagonia when it plowed into a large sperm whale, a collision that caused the ship to shudder and left a gaping hole in the hull.46 Capt. Edward Gardner, realizing that the pumps were no match for the torrent of sea water rushing into the hold, called for the men to abandon ship. Within a couple of hours the Union sank and Gardner and his crew of sixteen were left bobbing on the open ocean in the middle of the night in three whaleboats loaded with food, navigational instruments, water, books, and fireworks. “Our trust,” Gardner later recalled, “was on Divine Providence to bear us up and protect us from harm. Never was it more fully brought to my view than at this time, [that] ‘they that go down to the sea, and do business on the great waters, these see the wonders of the Lord in the mighty deep.’”47 Gardner set a course for the Azores, and after eight days and six hundred miles of sailing, they landed on Flores Island, from which they were later rescued.

Whereas the Union’s encounter with a whale was most likely an accident, the Essex’s was most definitely not. On November 20, 1820, the Essex was sailing near the equator, on the offshore grounds of the Pacific, when the lookout cried, “There she blows!”48 Capt. George Pollard, Jr., ordered whaleboats lowered and soon two of them were fast to whales. As the Essex sailed to meet these boats, Thomas Nickerson, a boy of fifteen who had been left to tend the wheel, saw a large whale, perhaps as much as eighty-five feet long, not more than one hundred yards from the port bow, quite still in the water and facing the ship. After diving briefly the whale surfaced again about thirty yards away. “His appearance and attitude,” wrote Nickerson, “gave us at first no alarm.”49 Then the whale began moving forward, powerfully thrusting its mighty flukes, reaching a speed of three knots, which equaled the speed of the ship that was heading toward it. Before the men on board could take evasive action, the whale struck, as first mate Owen Chase recalled, “just forward of the fore chains,” stopping the ship “as suddenly and violently as if she had struck a rock,” and nearly throwing “us all on our faces.” Water poured into the hold, and the whale continued under the ship, “grazing” the keel, and surfacing on the other side, about six hundred yards away, where it snapped its jaws open and shut and thrashed about in the water “as if distracted with rage and fury.” While the men manned the pumps, the whale once again made for the ship, coming twice as fast as before, “with,” Chase said, “tenfold fury and vengeance in his aspect,” and its head “about half out of the water.”50 The whale smashed the port bow and was moving with such velocity and continuing to pump its flukes with such strength that the Essex, a ship of nearly 240 tons, was pushed backward.51 The Essex’s tormentor, perhaps satisfied that his work was done, left the scene, and soon the ship listed sharply to port, giving the men just enough time to cut loose the whaleboats, get in, and pull away from the sinking hulk.

At the time of the ramming the Essex’s two whaleboats were miles from the ship, including one headed by Captain Pollard. When the whaleboats’ crews noticed that the ship was slowly disappearing from view, they became puzzled and deeply concerned, and quickly rowed back to investigate. On coming within hailing distance of Chase’s whaleboat, Pollard, dumbfounded, called out, “My God, Mr. Chase, what is the matter?” Chase, still scarcely able to believe what had happened, responded, “We have been stove by a whale.”52 The sinking of the Essex provided Herman Melville with the material he needed for the perfect climax to Moby-Dick. Had he waited just a while longer before penning his magnum opus, he would have had another example to draw on—that of the Ann Alexander.53

The Ann Alexander sailed from New Bedford on Saturday, June 1, 1850, thirty years after the Essex disaster. The beginning part of the cruise was successful, with the Ann Alexander capturing a number of good-size whales off Brazil, and then, in March 1851, heading round the Horn to the Pacific. The Ann Alexander reached the offshore grounds in August, and on the twentieth of that month, Capt. John Scott DeBlois saw sperm whales swimming in the distance. Three hours later one of the whaleboats harpooned a large bull, deemed to be “a noble fellow,” and DeBlois sang out, “Boys, pull for your dear lives! Get that whale and your voyage will be five months shorter.” But no sooner had the men fastened on than the whale turned, swam directly at its tormentors, and shattered the whaleboat between its jaws, sending the startled crew into the water. The whale “rushed through the wrecked boat two or three times, crushing the largest pieces left, in the wildest fury. The men were thrown hither and thither into the water, and climbing on the broken boat, were again dashed from it.”54 Two other whaleboats quickly rescued their soaked mates and set out after the offending whale. The chase had hardly commenced, however, when the whale turned again and repeated its earlier performance, “knocking” the second boat “all to pieces” and sending its crew overboard.55 DeBlois, shorn of confidence and fearful of the whale’s third act, had had enough. After collecting the second crew from the water, he turned the remaining whaleboat around and ordered the men to pull for the Ann Alexander, which lay seven miles away.

It was a hard row with “a heavy sea on,” and with eighteen men weighing down the boat, “every now and then,” a few of them “would have to jump overboard” while the rest bailed to keep the boat afloat. DeBlois thought the worst might be over, because the first few times he looked over his shoulder he saw the whale about a quarter to a half a mile off, floating at the surface. But the next time he looked the whale had disappeared. Then, “suddenly I heard under the boat a noise as of coach whips,” DeBlois remembered, “and I caught a glimpse of the whale coming for me. But he just missed the boat, and turning on his side, he looked at us, apparently filled with rage at having missed his prey. Had he struck us, not a soul of us could have escaped; for the ship knew nothing of our peril, and we were too far away to have reached it by swimming. It was indeed a narrow escape.”

Once the men made it back to the Ann Alexander, the whale reappeared about two miles off, and DeBlois, no doubt feeling less humble from his commanding perch aboard a massive ship, began sailing toward the whale, harpoon in hand, ready to launch his weapon should the gap be closed. “My blood was up,” DeBlois said, “and I was fully determined to have that whale cost what it might.” When the whale was within range, DeBlois threw a lance at its head, and at the same instant the whale hit the ship “with a dull thud,” knocking DeBlois “off the bow clean on the deck.” DeBlois commanded his men to lower a whaleboat and renew the chase at close quarters, but the crew was petrified into inaction. “If I was as big as you, and you, and you,” DeBlois screamed, pointing to his men, “I could eat that whale up!” but still they wouldn’t budge.

With the sun setting on the horizon, DeBlois could see the whale a half mile off, and he assumed that the battle was over. Then the whale started barreling toward the ship at an alarming rate. The Ann Alexander shuddered “from stem to stern” on impact, and the men were thrown to the deck. Water rushed in through the breach in the hull, and DeBlois ordered his men to cut the anchors and throw over the chains to lighten the ship in the hope of keeping it afloat. DeBlois then ran to his cabin to grab navigational equipment. Back on deck, sextant and chronometer in hand, DeBlois ordered the men into the two whaleboats, while he returned to his cabin to retrieve an almanac and some charts. Soon after DeBlois descended, a tremendous sea hit the ship, and the cabin filled with water. DeBlois swam for his life, and when he reached the upper deck he was “astonished” to discover that he had “been left alone on the doomed craft.” He called to his men, pleading with them to pick him up, but they ignored him. “You don’t know how quick this ship may sink,” screamed DeBlois over the waves, and then to his “great relief,” one of the boats came back for him.

The men spent a horrific night aboard the whaleboats near the wreck. Some of them accused the captain of getting them into this mess, to which DeBlois responded, “For God’s sake, don’t find fault with me! You were as anxious as I to catch that whale. I hadn’t the least idea that anything like this would happen.” DeBlois tried to comfort his men, but there little he could do or say to make them feel better about their plight. “Here were crowded into a small, weak boat a band of hungry sailors,” recalled DeBlois, “without a drop of water or a morsel of bread. The sea was running heavily, and the boat was leaking a good deal,” and they were two thousand miles from the nearest land. For the rest of the night, until dawn, the sounds of men sobbing and pleading for their lives punctuated the long hours of silence and fitful sleep.56

At first light DeBlois swam to the Ann Alexander, which was on its side, and using a hatchet, he cut away some of the masts, whereupon the ship righted slightly. Now men from the whaleboats scampered aboard and cut the other anchor free from the foremast, causing the ship to right further, giving them a chance to cut holes in the deck to search for stores below. The only items retrieved were two quarts of dried corn, six quarts of vinegar, a little barley, and a bushel of bread. Before leaving the wreck DeBlois scratched a message in the taffrail with a nail. “Save us; we poor souls have gone in two boats to the north on the wind.” All the men were familiar with the fate of the Essex, and they knew that unless something dramatic happened, they too might be forced to draw lots to see which of them would be eaten first. Fortunately, however, it didn’t come to that. After just two days at sea the men sighted a sail on the horizon and soon boarded the whaleship Nantucket.57 As for the whale, his tale had a sadder ending, being killed five months later by the men of the New Bedford whaleship Rebecca Sims. Identifying the whale, which yielded nearly eighty barrels of oil, was easy; two harpoons from the Ann Alexander and some wood from its hull were still embedded in its flesh.58

Just as Moby-Dick was about to be published, in 1851, Melville learned of the Ann Alexander’s misfortune. So carried away was he with the power of his own story that in a letter to a friend, commenting on the fate of the whaleship, Melville mingled fact with fiction. “I make no doubt,” wrote Melville, “it is Moby Dick himself, for there is no account of his capture after the sad fate of the Pequod about fourteen years ago.—Ye Gods! What a Commentator is this Ann Alexander whale. What he has to say is short & pithy & very much to the point. I wonder if my evil art has raised this monster.”59

The Ann Alexander’s tale made a considerable splash in the press. Whaling stories were in vogue, and a story about a whale sinking a ship was simply too good to ignore. Not every news outlet, however, took it seriously. The Utica Daily Gazette argued that the Ann Alexander’s story was too fantastic to be believed, especially the parts dealing with the escape of the men from the sinking ship and their subsequent efforts to salvage what they could. The editorialist claimed, in fact, that feats such as cutting away masts and parting anchor chains surpassed those of “Jack the Giant Killer or Saladin.” The Gazette’s incredulity brought a quick and sharp response from the Whalemen’s Shipping List, whose editors questioned why a newspaper located in the center of New York State, far from the ocean, should think itself knowledgeable enough to offer any commentary on the subject. The writer for the Gazette “may be remarkably well posted upon the navigation of mill-ponds,” wrote the Shipping List’s editors, “and the stormy terrors of the ‘raging canawl,’ but we opine that he gets altogether out of his depth when he undertakes the task of throwing doubt upon the account given by Capt. DeBlois of the loss of his ship.”60

Mutinous men, murderous natives, and seemingly vengeful whales were some of the most merciless foes that the whalemen ever faced. But as whaling entered the twilight of the golden age, there were new enemies on the horizon that would be much more relentless and damaging than any the industry had faced before, and that would ultimately defeat the American whalemen.