Chapter Seventeen

STONES IN THE HARBOR AND FIRE ON THE WATER

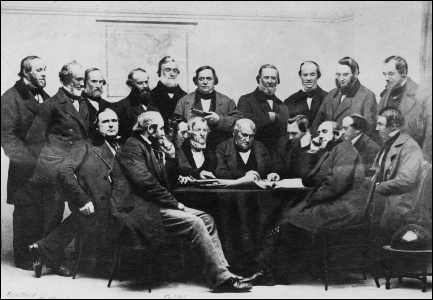

THE CAPTAINS OF THE STONE FLEET GATHER IN 1861 TO RECORD THEIR INVOLVEMENT IN THE SINKING OF STONE-FREIGHTED WHALESHIPS IN CHARLESTON HARBOR, SOUTH CAROLINA. PHOTOGRAPH BY THE BIERSTADT BROTHERS.

TOWARD THE END OF THE 1850S, EVEN AS WHALESHIP OWNERS were still counting their profits, many of them looked with foreboding to the future and the increasingly inevitable conflict between the North and the South, which would be ignited in 1861 and engulf the nation for four and a half long and exceptionally bloody years. Like the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812, the Civil War had a crippling effect on American whaling. Many whaleship owners, faced with the increasing difficulty of obtaining insurance for whaling voyages, idled their ships and sought land-based outlets for their capital. Others took “flight from the flag” and registered their ships with foreign nations in an effort to skirt the war. The demand for whale oil in the North plummeted, as kerosene became the illuminant of choice, while the pipeline of whale oil flowing to the South was completely cut off. In fact, during the course of the war, the American whaling fleet contracted by roughly 50 percent.1

From the outset of the war the Union sought to place a stranglehold on Confederate commerce to prevent the flow of supplies. The Union also hoped to keep the South from sending privateers to attack Union shipping. Capitalizing on its vast naval superiority, the Union planned to seize commercial and military vessels traveling to and from the South. But there was, Union military strategists thought, another way to choke the Confederacy: Why not sink a large number of ships in the channel leading to Savannah’s harbor, making it impassable? Deciding to pursue this course in the fall of 1861, Gideon Welles, the secretary of the Union navy, instructed a team of purchasing agents to obtain “twenty-five old vessels of not less than 250 tons each for” this purpose. The ships were to be loaded with blocks of granite to weigh them down, and in each vessel’s hull there was to be placed a “pipe and valve” so that on anchoring, the valve could be opened and the ship scuttled.2 The purchasing agents located the readiest source of old ships available for a good price—the fleet of Northern whaleships. Whaleship owners, already experiencing a dramatic decrease in demand for whaling products, were more than willing to sell their ships for both economic and patriotic reasons. At the bargain price of about ten dollars per ton, the purchasing agents quickly obtained the twenty-five vessels, twenty-four of which were whaleships, with fourteen coming from New Bedford and Fairhaven, five from New London, two from Mystic, and one each from Nantucket, Edgartown, and Sag Harbor. The final vessel was a New York merchant ship. The whaleships ranged from around 250 to 600 tons, and while some had recently returned from whaling voyages, others were quite old, with two of them approaching one hundred, and all of them had seen better days. This most unusual group of ships—sacrificial lambs for the Union cause—was dubbed the Stone Fleet in honor of its intended cargo.3

Everything of value was stripped from the ships and sold at auction. Although the navy had requested that the ships be filled with granite blocks, the granite was not as readily available as fieldstone, and soon farmers, getting fifty cents per ton, were doing a brisk business dismantling their rock walls and carting them to the docks. Cobblestones, too, were ripped from the streets until 7,500 tons of stone were collected and placed in the ships’ holds.4 The Stone Fleet’s captains, many of them former whaling masters, and their skeleton crews, were ordered to proceed directly to Savannah, where they were to deliver their ships “to the commanding officer of the blockading fleet.”5 Originally conceived as a clandestine operation, the outfitting of the Stone Fleet was so massive that it became an open secret among New Englanders who were eager to do their part to support the war and weaken the Confederacy. The Stone Fleet’s departure from New Bedford, on November 20, 1861, was the occasion of a public celebration, with the revenue cutter Varina leading the fleet into the bay, while thousands of spectators cheered and loud blasts from signal guns and a thirty-four-gun salute from Fort Taber heralded the procession.6 The New Bedford Mercury noted that blocking harbors in this manner was “an exceedingly pacific mode of carrying on the war, [and that] all of our citizens will join in wishing it success.”7 On November 22 the New York Times declared, with characteristic nineteenth-century bluster, “The rebels cannot but regard our proceedings with terror and dismay. They cannot lift a finger in resistance, or to prevent the cities through which their commerce has been carried on from becoming desolate wastes. They have tasted many a bitter cup since the rebellion broke out, but this last one is the most fatal chalice yet commended to their lips.”8

The stormy voyage from New Bedford to Savannah was difficult for the old fleet, which finally began arriving in early December. The commanding officer for the Savannah blockade, J. S. Misroon, complained to his superior, Flag Officer Samuel F. DuPont, that there were “few good vessels among them and all badly found in every respect,” noting that “several had arrived in sinking condition.”9 Whether the fleet was sinking or not, its arrival had a terrifying effect on the Confederate forces, who thought that it signaled the beginning of a Union invasion. It was a natural mistake. Some of the whaleships had false gun ports painted on their sides, called “Fiji ports,” which had been placed there years before to fool would-be attackers into thinking that the whaleships were warships bristling with cannons, and therefore should not be trifled with.10 It certainly confused the Confederates, who, fearing a major assault by a superior Union force, torched a lighthouse, fled some of their defensive positions, and reinforced Fort Pulaski, near the mouth of the Savannah River. The Confederates, however, weren’t fooled for long. Soon after arriving the Stone Fleet literally began to fall apart. The Meteor and the Lewis grounded, and the Phoenix, “leaking badly,” was intentionally sunk near shore along with three other ships, the Cossack, the South American, and the Peter Demill, all of which were used to create a “breakwater and bridge” to land supplies and Union troops on Tybee Island.11

As it turned out, the Stone Fleet’s services weren’t needed. The Confederates beat the Union forces to the punch by sinking a few old vessels in the channel leading to Savannah to keep the Yankee fleet out. This strategic maneuver played right into the hands of the Union and provided DuPont with an opportunity to poke fun at the enemy. In a letter to Gustavus V. Fox, the assistant secretary of the Union navy, DuPont observed that Confederate naval captain Josiah Tattnall “is doing all the work for us…I sent word to Misroon to get [Tattnall]…word if he could, that we would supply him with half a dozen vessels to help his obstruction of Pulaski.”12 The Confederate blockade of Savannah allowed what was left of the Stone Fleet to be redirected to a second target, Charleston, another critical Southern port, where Capt. Charles Henry Davis, the chief of staff under DuPont, was waiting to take charge. Davis, who was an expert on navigation and the effects of tides and currents, did not welcome this assignment. “The pet idea of Mr. Fox has been to stop up some of the southern harbors,” Davis observed. “I had…a special disgust for this business…. I always considered this mode of interrupting commerce as liable to great objections and of doubtful success.” Another time Davis called Fox’s preoccupation with placing obstacles in Southern harbors a “maggot in his brain.”13

Despite these misgivings Davis carried out his job and oversaw the sinking of sixteen ships of the Stone Fleet across the mouth of Charleston’s main shipping channel, a task that was completed by December 20 (the few remaining ships of the first twenty-five were converted to use as storage and coaling vessels for Union forces). Davis laid the ships out in what DuPont referred to as “checkerboard or indented form, lying as much as possible across the direction of the channel,” the hope being that this design would facilitate the shoaling of sand around the hulks and thereby form an impenetrable barrier to navigation.14 Once the ships were in place their crews stripped them of valuable cordage and supplies that could be used by the enemy, cut away their masts, and then scuttled them by opening the valves on the pipes inserted into the hulls. All the ships sank under the waves, with one exception, the Robin Hood, which had settled on a sandbar with its main deck still well above the water. The men took advantage of this during their operation, piling the Robin Hood’s deck high with materials taken from the other ships, such as damaged sails, frayed lines, and worn-out blocks. But they couldn’t leave the Robin Hood in this exposed position for fear that it might be used by Confederate ships as a landmark to guide them into port. So at dusk the Robin Hood was set ablaze. The Union commanders had hoped to create a conflagration of epic proportions that would light up the sky with a dazzling display and strike fear into the hearts of the Confederate onlookers, but the fire burned only fitfully, with more smoke than flames, and it was many hours before the ship burned down to the waterline and the fire was extinguished.

Shortly after the first twenty-five vessels were purchased, Welles ordered that another twenty be obtained, which was easier said than done. The first buying spree had stripped many of the whaling ports of their oldest, least seaworthy, and cheapest ships, forcing the purchasing agents to look farther afield and, in many instances, pay higher prices to get the additional ships—fourteen whaleships and six merchantmen.15 This second Stone Fleet was prepared for scuttling and sent south toward the end of December 1861, in the same manner as the first, with Charleston as its ultimate destination. There, on January 25–26, 1862, most of the fleet was sunk across Maffitt’s Channel, in the signature checkerboard fashion.

A reporter for the New York Times, watching the sinking of the Stone Fleet’s first squadron, grew nostalgic and wistful.

Who could help feeling melancholy at the reflection that the poor old vessels, which had traversed so many thousands of miles of ocean, safely carrying human beings amid Pacific calms and Arctic colds through long years of dreary, tedious whaling voyages, were to be relentlessly destroyed?…Short, broad, square-sterned, bluff-bowed…. Queer old tubs with queer fittings-up, and quaint names set in elaborate beds of quaint carved work. Yet many of these fossil vessels were celebrated in their time. The fortunes of the Tabers, the Howlands, the Sims’, Swifts, Coffins, Starbucks and many other New England families have been created from their voyages.16

While the sinking of the Stone Fleets created a psychological boost for the North, it was viewed in the South as yet another example of the Union’s perfidy.17 Gen. Robert E. Lee called “this achievement, so unworthy [of] any nation…the abortive expression of the malice and revenge of a people.”18 Many observers in Britain and France joined in the chorus of condemnation. The Times of London kept up a particularly biting line of attack, writing in several issues, “Among the crimes which have disgraced the history of mankind it would be difficult to find one more atrocious than this” “No belligerent has the right to resort to such a warfare” and “People who would do an act like this would pluck the sun out of the heavens, to put their enemies in darkness, or dry up the rivers, that no grass might for ever grow on the soil where they had been offended.”19 Even foreigners who strongly supported the Union had little good to say about the Stone Fleet, as evidenced by a letter from a British manufacturer, John Cobden, to Massachusetts senator Charles Sumner.

I am not pleased with your project of sinking stones to block up ports! That is barbarism. It is quite natural that, smarting as you do under an unprovoked aggression from slave-owners, you should even be willing to smother them like hornets in their nest. But don’t forget the outside world, and especially don’t forget that the millions in Europe are more interested even than their princes in preserving the future commerce with the vast region of the Confederate States.20

Given the extent of the hostility registered from overseas, compounded by the fear that such outrage might induce Britain to break the blockade, possibly precipitating another war, the Union could not simply ignore the criticism. Thus William H. Seward, the Union secretary of state, let it be known through official diplomatic channels that the sinking of the Stone Fleet was never “meant to destroy the harbor permanently. It was only a temporary measure to aid the blockade, and it was well understood that the United States would remove the obstructions after the war was over.”21 And to allay any lingering concerns that sinking stone-laden vessels in Southern harbors was an ongoing policy, Seward added that there were no plans to employ this tactic again.

All the acrimony was for naught. If the Stone Fleet impeded traffic at all, it was only for a very short while, and certainly not long enough to have any measurable impact on the outcome of the war, except perhaps to inflame the passions of the Confederacy. Powerful currents coursed around the wrecks and scoured out new channels. Swarms of marine worms soon riddled the ships with holes. As the ships’ already elderly skeletons weakened, pieces of planking and ribbing broke free and washed up on nearby shores. And all the while these heavy hulks, weighted down by tons of stone, sank into the mud and sand. A coastal survey in May 1862 found that parts of Charleston’s main channel were deeper than they had been before the Stone Fleet arrived, and when another survey was conducted the following year, all evidence of the fleet had simply disappeared.22 The final requiem for the Stone Fleet came from Melville’s pen, in the form of a poem he published in 1866, which he called, “The Stone Fleet, An Old Sailor’s Lament.”

I have a feeling for those ships,

Each worn and ancient one,

With great bluff bows, and broad in the beam:

Ay, it was unkindly done.

But so they serve the Obsolete—

Even so, Stone Fleet!

You’ll say I’m doting; do but think

I scudded round the Horn in one—

The Tenedos, a glorious

Good old craft as ever run—

Sunk (how all unmeet!)

With the old Stone Fleet.

…………………

And all for naught. The waters pass—

Currents will have their way;

Nature is nobody’s ally; ’tis well;

The harbor is bettered—will stay.

A failure, and complete,

Was your Old Stone Fleet.23

THE SOUTH ALSO WANTED to sink Northern whaleships, but not in the manner of the Stone Fleet. Instead the Confederacy’s goal was to seek out and destroy whaleships as part of a much larger naval strategy aimed at crippling the Northern economy and forcing Union warships to shift from blockading Southern ports to protecting the Union’s assets at sea. But to implement this strategy, the confederacy needed ships they didn’t have. When the war broke out the Union seized almost all of the United States Navy, as well as a massive merchant fleet, and the South was left in the unenviable position of having to build a navy of its own, largely from scratch. Although the South had plenty of wood, it lacked the other critical resources necessary for building and fitting out warships, including iron, ammunition, and the skilled workmen to do the job; reflecting the fact that the North had greatly industrialized over the previous decades while the South remained agrarian, its economy based to a large degree on slave labor.

Even if the resources and workmen had been available, there were no facilities to build the ships. There was only one manufacturer in the entire Confederacy capable of building a “first-class marine engine,” and the South’s main shipyard, at Norfolk, had been greatly damaged by Northern forces.24 If the South was to rebuild at Norfolk and launch new warships, it would still have to run the gauntlet through the powerful Union blockade, a virtual impossibility given how many guns were trained on Norfolk’s exit to the sea. Rather than give up on its desire for a navy, the Confederacy looked across the ocean for assistance, and Confederate president Jefferson Davis and his secretary of the navy, Stephen R. Mallory, sent special agents to Europe to arrange for the building of warships. One of those agents was James D. Bulloch, and of the twelve vessels he obtained for the South, none were more feared by whalemen than the Alabama and the Shenandoah.

Bulloch, a native of Georgia who had spent many years in the U.S. Navy and then the merchant service, was by all accounts shrewd, diplomatic, decisive, and thoroughly knowledgeable in naval affairs, and his role as agent for the Confederacy required that he use all his talents to their utmost.25 Bulloch arrived in England in the summer of 1861 and immediately began commissioning ships for the Confederate navy, but he had to be extremely careful to conceal their true purpose. Britain had declared itself neutral during the Civil War, and the Foreign Enlistment Act of 1819 forbade any British subject from arming or outfitting any vessel for use by a belligerent power. Thus if the British authorities determined that a shipyard was engaged in supplying a warship for the Confederacy, it would be violating the act and its operations would be shut down and the ship confiscated. Bulloch avoided this outcome by exploiting a loophole in the law. Although it was clearly illegal for a British shipyard single-handedly to build, arm, and outfit a warship for a belligerent, it was perfectly legal, according to the lawyers Bulloch consulted, to have all these acts be performed by different vendors; the key was keeping the elements of the enterprise separate from one another, and that is exactly what Bulloch did. So well, in fact, that even though the North soon caught on to Bulloch’s ploy and pleaded with the British government to confiscate the ships he was building, the government said that it couldn’t because Bulloch wasn’t violating the law. In this manner the CSS Alabama was launched from Birkenhead Iron-works in Liverpool on July 29, 1862.

At 210 feet long the Alabama was a beautiful, sleek, and fast ship. “Her model was of the most perfect symmetry,” observed Capt. Raphael Semmes of his new command, “and she sat upon the water with the lightness and grace of a swan.”26 With auxiliary steam power the Alabama had the luxury of running down prizes and escaping from enemies in dead calms, when sail-driven ships could only drift. After departing from Liverpool the Alabama sailed to the Azores, where it was armed and provisioned by a supply ship sent by Bulloch. Now the Alabama was ready to seek out and destroy Union shipping wherever it could be found, and Semmes, “following Porter’s example in the Pacific…resolved to strike a blow at the enemy’s whale fishery off the Azores.”27

On September 5, seeing a ship in the distance, the Alabama raised a U.S. flag and went to investigate. It was the Ocmulgee, a whaleship out of Edgartown, and it was so busily engaged in the process of cutting into a large sperm whale that it took little notice of the Alabama and, seeing the Union colors flying on its mast, had no reason to be concerned. Indeed Semmes learned later that the Ocmulgee’s master had thought the Alabama to be a military ship sent by Union navy secretary Welles, to protect the American whaling fleet from attack. “The surprise was,” Semmes wrote, “perfect and complete…. [the Ocmulgee’s master, Abraham Osborne] was a genuine specimen of the Yankee whaling skipper; long and lean, and as elastic, apparently, as the whalebone he dealt in. Nothing could exceed the blank stare of astonishment that sat on his face as the change of flags took place on board the Alabama.”28 Osborne was not merely astonished, he was furious. “This is a disgraceful act,” Osborne told Semmes, “you flying the United States colours until you come right alongside my ship and only then exchanging them for your Confederate flag.” Semmes saw things a little differently, telling Osborne, “I see your point, but this is war and my tactics were quite legitimate.”29

Osborne was ordered to bring his ship’s papers and chronometer to Semmes’s cabin. Semmes perused the papers, then looked up at the captain. “So you’re from Edgartown,” Semmes purportedly said. “I thought so. You’re the kind we are looking for. Anything from that blackhearted Republican town we must burn if it comes within reach.”30 As Semmes was saying this, Osborne observed him carefully. He thought Semmes looked familiar, and then it came to him. Before the war Semmes, then a U.S. naval officer, had visited Edgartown to purchase whale oil for government use, and Osborne’s parents had had him over for dinner. Osborne mentioned this, but his family’s prewar hospitality meant nothing to Semmes now. Northerners were the enemy, and he had his orders. Semmes proceeded to transfer the thirty-seven whalemen, along with provisions, to the Alabama, and then burned the Ocmulgee. He had no intention of harming the whalemen, who were noncombatants, and after paroling them he let them row their whaleboats to a nearby island, from which they were later rescued.

Over the next two weeks, as the whaling season off the Azores wound down, the Alabama captured and burned eight more whaleships. Reflecting on the ease with which he bagged these prizes, Semmes wrote, “It was indeed remarkable, that no protection should have been given to these men, by their Government. Unlike ships of commerce, the whalers are obliged to congregate within small well-known spaces of the ocean, and remain there for weeks at a time, whilst the whaling season lasts.” One of Semmes’s prizes was the Ocean Rover, a New Bedford whaleship that had been out for more than three years in the Indian and Atlantic Oceans, whose captain had decided to stop off in the Azores on the way home to top off his voyage with the oil of a few more whales. Soon after the Ocean Rover was captured, its captain asked Semmes if he and his men could be accorded the same opportunity as the men of the Ocmulgee, to row ashore. Semmes, noting that the Alabama was four or five miles from land, wondered aloud whether the captain really wanted to row that far. “Oh! That is nothing,” the captain replied. “We whalers sometimes chase a whale on the broad sea, until our ships are hull-down and think nothing of it. It will relieve you of us sooner and be of some service to us besides.” Semmes consented and gave the whalemen time to return to the Ocean Rover and load six whaleboats with their belongings and provisions. When the whaleboats returned, overflowing with “plunder,” Semmes, somewhat amused by the scene, said, “Captain, your boats appear to me to be rather deeply laden; are you not afraid to trust them?” The cheery captain replied, “Oh! No, they are as buoyant as ducks, and we shall not ship a drop of water.” And with that Semmes, who possessed a literary flair even Melville might have admired, watched as the whalemen departed under the moonlit sky. “That night landing of this whaler’s crew was,” Semmes wrote, “a beautiful spectacle…. The boats moving swiftly and mysteriously toward the shore might have been mistaken, when they had gotten a little distance from us, for Venetian gondolas with their peaked bows and sterns.”

In later reports the Northern press would claim that Semmes intentionally burned the whaleships at night, using the flaming beacons as bait to draw in other victims, relying on sailors’ natural and honorable impulse to aid fellow sailors in distress. Such reports greatly offended Union sensibilities, but they reflected Northern propaganda and simply weren’t true. Semmes was much smarter than that: “A bonfire by night,” he knew, “would flush the remainder of the game…in the vicinity; and I had become too old a hunter to commit such an indiscretion. With a little management and caution, I might hope to uncover the birds no faster than I could bag them.” The Northern press also demonized Semmes, labeling him no better than a pirate. However, from where Semmes sat, his actions seemed quite reasonable. His beloved South was at war, and it was his responsibility to strike at the enemy however he could. When captains pleaded with Semmes not to set fire to their ships, he responded, “Every whale you strike will put money into the Federal treasury, and strengthen the hands of your people to carry on the war. I am afraid I must burn your ship.”31 Semmes commented later that, “The New England wolf was still howling for Southern blood, and the least return we could make for the howl, was to spill a little ’ile.’”32 Semmes’s officers shared his contempt for the North, and shortly after President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, a couple of them left a two-by-four-foot carved wooden tombstone on an island the Alabama visited, which read, in part, “In memory of Abraham Lincoln, President of the late United States, who died of Nigger on the brain. 1st January 1863.”33

For nearly two years the Alabama pursued its mission of destruction, in the end capturing or burning nearly 70 Union vessels, fourteen of them whaleships. The end came on June 19, 1864, when the Alabama, which had pulled into Cherbourg, France, for much-needed repairs, left the port to engage the USS Kearsarge, which had been sent to hunt it down. The battle, which was witnessed by throngs of observers from the shore, ended when the hull and rudder of the outmatched Alabama was shattered by a cannon-ball strike just beneath the waterline, causing the ship to sink.34 Within weeks of the Alabama’s demise, Confederate leaders, desperate to grab onto any scheme that might turn the tide of the war in their direction, asked Bulloch if there was another vessel that could replace the Alabama in order to continue to attack Union shipping. Bulloch responded in late summer by purchasing the Sea King, an East India merchantman docked in England that was quite similar to the Alabama, being about the same size and with auxiliary steam power, but the Sea King was the faster of the two, having traveled on one occasion 330 miles in twenty-four hours.35 Using the same secrecy and deception that had become his hallmark, Bulloch completed his preparation of the new Confederate raider before Union representatives, fearing that the Sea King was to be another Alabama, could induce the British government to halt its departure. When the Sea King left the Port of London on October 8, 1864, its manifest claimed that it was nothing more than a merchant ship heading to Bombay, but British India was most definitely not on its itinerary.

In a little more than a week the Sea King made it to Madeira, off the coast of northwestern Morocco, where it rendezvoused with the Laurel, a Bulloch-sponsored steamer full of the cargo necessary to outfit and arm the raider. Also on board the Laurel was Capt. James I. Waddell, who would soon have the Sea King under his command. Waddell, who walked with a limp courtesy of a dueling injury, had been born in North Carolina. In the years prior to the Civil War he had achieved considerable success in the U.S. Navy, rising to the rank of lieutenant, but when his beloved North Carolina seceded, Waddell left the navy to serve the Confederacy, writing in his letter of resignation that, “I wish it to be understood that no doctrine of the right of secession, no wish for disunion of the States impels me, but simply because, my home is the home of my people in the South, and I cannot bear arms against it or them.” After most of the Laurel’s cargo had been transferred to the Sea King, Waddell came on deck dressed in his Confederate navy uniform and informed the assembled crews of the Laurel and the Sea King that the latter had been purchased by the South and was now the CSS Shenandoah. Before the dumbfounded men could fully absorb this revelation, Waddell “asked them,” as he later recalled, “to join the service of the Confederate states and assist an oppressed and brave people in their resistance to a powerful and arrogant northern government.”36

Waddell had brought with him, on the Laurel, only eighteen handpicked officers and crew. While they were good and dependable men, a few of whom had seen duty on the Alabama, there simply weren’t enough of them effectively to man the Shenandoah. So convinced were Bulloch and Waddell of their cause, that they had hoped at least sixty out of the eighty crew members of the Laurel and the former Sea King would sign on to the Shenandoah, but only twenty-three did, bringing the Shenandoah’s total complement to a paltry forty-two, still far fewer than the 150 men who would be wanted for a warship of its size.37 Waddell, although severely disappointed, accepted this outcome with steely composure and told those who rejected his offer to board the Laurel, which would take them back to England. Then Waddell ordered his men to get under way, but that proved easier said than done. There were not enough crew members to haul up the anchor, forcing Waddell and his officers to shed their coats and give the men a hand. With the anchor secured, the Shenandoah’s career as a Confederate raider began.

Waddell’s orders were clear. “You are about to proceed upon a cruise in the far-distant Pacific,” read the letter from Bulloch, “into seas and among the islands frequented by the great American whaling fleet, a source of abundant wealth to our enemies and a nursery for their seamen. It is hoped you may be able to greatly damage and disperse that fleet, even if you do not succeed in utterly destroying it.”38 Although the ultimate goal of the cruise was to damage the whaling fleet, the Shenandoah did not pass up the chance to gain other prizes when such opportunities arose, and within six weeks of leaving Madeira, Waddell and his men had captured six merchant vessels, scuttling or burning all but one of them, which was used to transport prisoners to Brazil.

On December 4, 1864, not long after Union general William Tecumseh Sherman began his infamous March to the Sea through Georgia and the Carolinas, the Shenandoah encountered its first whaleship, the Edward of New Bedford, just fifty miles from the island of Tristan da Cunha in the South Atlantic Ocean. The men of the Edward Carey were so busy cutting into a right whale that they did not notice the Shenandoah until it was within close range.39 The Edward Carey was well provisioned, and the Shenandoah stood by it for two days, stripping it of much needed supplies, including cotton canvas, blocks, one hundred casks of beef and pork, and thousands of pounds of hardtack, which was, according to Waddell, “the best we had ever eaten.” The Edward Carey was then set ablaze. Waddell didn’t enjoy burning his prizes; it was simply the most effective and efficient way to dispose of them.

The captain and crew of the Edward Carey were taken to Tristan da Cunha, an island that had been used since the early 1800s by whalemen and sealers as a stopping-off point, and which now had a population of about forty, most of whom were of either American or British lineage.40 On nearing the island, the Shenandoah was greeted by locals in a canoe who wanted to barter for supplies. When one of the islanders looked to the masthead and saw the Confederate flag, he asked what it was. When they were informed that the Shenandoah was a Confederate cruiser and that there were prisoners on board whom the Confederates planned to leave on the island, the islander responded:

“And where the devil did you get your prisoners?”

“From a whaler not far from here,” replied one of the Shenandoah’s officers.

“Just so, to be sure; and what became of the whaler?”

“We burned her up.”

“Whew! Is that the way you dispose of what vessels you fall in with?”

“If they belong to the United States; not otherwise.”

“Well, my hearty, you know your own business, but my notion is that these sorts of pranks will get you into the devil’s own muss before you are through with it. What your quarrel with the United States is I don’t know, but I swear I don’t believe they’ll stand this kind of work.”41

Their concern for the Confederates notwithstanding, the islanders, whose governor was a Yankee no less, agreed to take the prisoners, who stayed on the island for three weeks until they were rescued by the USS Iroquois, which had been sent to pursue the Shenandoah.42

Soon after the Shenandoah left Tristan da Cunha, one of the crewmembers discovered a cracked coupling band on the propeller shaft. Instead of going to Cape Town, the closest port where the needed repairs could be made, Waddell took a risk and continued on his intended course to Melbourne, Australia, under sail. When the Shenandoah arrived, it was an instant sensation. According to Cornelius Hunt, acting master’s mate on the Shenandoah, “Crowds of people were rushing hither and thither, seeking authentic information concerning the stranger, and ere we had been an hour at anchor, a perfect fleet of boats was pulling toward us from every direction.”43 Waddell officially requested the local governor’s permission to make repairs to the Shenandoah as quickly as possible and take on a load of coal for its subsequent voyage. The governor, nervous about hosting a Confederate raider and mindful of Britain’s official stance of neutrality, ultimately consented, and thus began the Shenandoah’s nearly four-week stay in Melbourne. After Waddell agreed to allow visitors, “the news spread like wildfire,” wrote Hunt. Thousands of people, “all eager to say that they had visited the famous ‘rebel pirate,’” came aboard.44 The U.S. consul in Melbourne had a much dimmer view of the proceedings. Incensed about the courtesy afforded the Shenandoah, he repeatedly urged the governor to seize it, but to no avail.

Its repairs complete and its coal hoppers full, the Shenandoah left Melbourne on February 18, 1865, the day on which Fort Sumter was recaptured by Union forces. While in Melbourne, hundreds of Australians, sympathetic to the Confederate cause, asked to ship out on the Shenandoah, but Waddell and his officers had politely refused them, not wanting to run afoul of Britain’s Foreign Enlistment Act. It was a bitter pill to swallow because seventeen men had deserted the already undermanned Shenandoah while it was being repaired, apparently induced to do so, Waddell claimed, by one-hundred-dollar bribes from the U.S. consul.45 But no sooner had the Shenandoah gotten under way than men literally began to crawl out of the woodwork. All told, forty-five new recruits had smuggled themselves on board, most likely the night before departure. They had been hiding in the hollow bowsprit, the empty water tanks, and the lower hold. “How such a number of men could have gained our decks unseen was a mystery to me,” said Hunt, “but there they were, and the question now was, how to dispose of them.”46 Despite Hunt’s surprise, the stowaways, all of whom claimed to be “natives of the Southern Confederacy,” were undoubtedly helped on board, as one midshipman argued, “with the knowledge and connivance of the crew.”47 Knowing full well that he desperately needed these men, Waddell decided that what was done was done, and the stowaways could stay.

The Shenandoah sailed next to the Caroline Islands, where it captured four whaleships. Rather than burn these prizes, Waddell had them run aground to allow the natives to strip them of whatever they wanted, and in return for this indulgence the native king agreed to take 130 whalemen off Waddell’s hands and host them until another U.S. ship happened by. These whaleships provided an unexpected windfall in the form of charts the whalemen used in hunting whales. “With such charts,” observed Waddell, “I not only held a key to the navigation of all the Pacific Islands, the Okhotsk and Bering Seas, and the Arctic Ocean, but the most probable localities for finding the great Arctic whaling fleet of New England, without a tiresome search.”48 Thus armed and eager to engage that fleet, the Shenandoah headed north, battling through typhoons and gales, and arriving off the Kamchatka Peninsula in late May, where it captured and burned the New Bedford whaleship Abigail.49

Nobody was more surprised by this turn of events than the Abigail’s captain, Ebenezer Nye. He had pegged the Shenandoah as a Russian vessel, and was amazed to discover its true identity. When Nye asked what a raider was doing in those waters, he was informed by one of the Shenandoah’s officers that, “the fact of the business is, Captain…we have entered into a treaty offensive and defensive with the whales, and we are up here by special agreement to disperse their mortal enemies.” Nye, reflecting on the relatively poor success of his trip thus far, responded, “The whales needn’t owe me much of a grudge, for the Lord knows I haven’t disturbed them this voyage, though I’ve done my part at blubber hunting in years gone by.”50 But Nye was far unluckier than that. This was not his first experience with a Confederate raider. He had been on one of the whaleships captured and burned by the Alabama, leading one of his forlorn crew to exclaim, “You are more fortunate in picking up Confederate cruisers than whales. I will never again go with you, for if there is a cruiser out, you will find her.”51 Nye may have been unlucky, but he didn’t lack courage. While watching his ship go up in flames, Nye told Waddell, “You have not ruined me yet; I have ten thousand dollars at home, and before I left I lent it to the government to help fight such fellows as you.”52

As he had done with all his earlier captures, Waddell asked the Abigail’s crew if any of them wanted to join the Shenandoah and help fight for the Southern cause. One who did was the second mate, Thomas S. Manning, a native of Baltimore who, through mendacity and obnoxiousness, soon managed to become thoroughly despised by the Shenandoah’s crew.53 The addition of Manning, however, was not a total loss. He provided a valuable service, using his knowledge of the Northern whaling fleet’s movements to guide the Shenandoah to its prey. On June 21, off Cape Navarin in the Bering Sea, the Shenandoah picked up the trail, encountering blubber floating in the water, indicating that there were whaleships nearby. Two sails were soon sighted, and before long the Shenandoah captured and burned the whaleships William Thompson and the Euphrates, both from New Bedford. The next day the Shenandoah captured three more New Bedford whaleships, the Milo, the Sophia Thornton, and the Jireh Swift. The last of two of these provided the Shenandoah with a bit of excitement. Unlike the other whaleships the Shenandoah had captured, the Sophia Thornton and the Jireh Swift, both of whom had watched the Shenandoah overhaul the Milo, made a run for it, lowering their sails and heading into the ice fields.54 The Shenandoah, with its steam engine pumping, set off after the two, drawing close to the Sophia Thornton first. A couple of warning shots from the Shenandoah’s thirty-two-pound Whitworth rifle, one of which tore through the Sophia Thornton’s topsail, convinced her captain to surrender. Meantime the much faster Jireh Swift sailed free of ice and was heading for the Siberian coast. Using both steam and sail power, the Shenandoah pursued it, moving through the water at eleven-plus knots, but even at that impressive speed it took three hours before the Shenandoah was able to get within shelling range, at which point, Waddell observed, “Captain Williams, who made every effort to save his bark, saw the folly of exposing her crew to the destructive fire and yielded to his misfortune with a manly and becoming dignity.”55

Waddell’s success was creating a problem. With each ship captured, the number of prisoners increased, to the point where they couldn’t safely be held on board the Shenandoah, and since Waddell didn’t want to leave the men among the ice floes, an almost certain death sentence, he had to come up with another plan. So he ransomed one of the ships. Waddell invited the Milo’s captain, Jonathan C. Hawes, onto the Shenandoah and offered him a deal: Waddell would spare the Milo if Hawes agreed to give a bond of $46,000 and take all the prisoners to San Francisco.56 The bond, which was equal to the value of the ship and its contents, was intended to serve as an IOU that would be paid by the Milo’s owners to the Confederacy at the end of the war. Hawes quickly consented, and the Milo, with its human cargo, sailed south, leaving behind the Sophia Thornton and the Jireh Swift, both of which were burned. As for the bond, it was never paid, a fact that still rankled Hunt years later when he wrote a book about his time on the Shenandoah.

This and a number of similar vouchers taken by us during our cruise, have not yet been paid, and if they ever intend to take up these obligations, no better time than the present will ever offer. To be sure the war terminated disastrously to our cause, but we are, therefore, so much the more in need of any trifling sums that may be owing to us. The above amounts, therefore, may be sent to me, care of my publisher, who is hereby authorized for receipt for the same.57

Ever since leaving Australia the Shenandoah had been virtually cut off from the outside world, leaving Waddell and his men to wonder and worry about the progress of the war. Thus, before the Milo departed, Waddell asked Captain Hawes the same question that he posed to all the captains whose ships he had captured—did he have any news from the States? Hawes’s response, that the war was over, agitated Waddell. Unwilling to accept the captain’s word at face value, Waddell asked him for proof, and when the captain couldn’t provide such evidence, Waddell relaxed, assuming that the captain’s intelligence was incorrect. But Waddell’s confidence would soon be shaken. Two days later the Shenandoah captured and burned the Susan Abigail, a trader recently sailed from San Francisco. On board the Abigail were California newspapers that contained dire news about the South, reporting on Grant’s victory at Richmond, Lee’s surrender at Appomattox, and the removal of President Jefferson Davis and the rest of the Confederate government to Danville, Virginia. Waddell also read with keen interest news of Lincoln’s assassination and a proclamation issued by Davis, in which he urged Southerners to carry on the war “with renewed vigor, and exhorting the people of the South to bear up heroically under their calamities.”

Waddell then asked the Susan Abigail’s captain what Californians thought about the likely outcome of the war. “Opinion is divided,” he said. “For the present the North has the advantage, but how it will all end no one can know, and as to the newspapers they are not reliable.”58 That was exactly what Waddell wanted to hear. He couldn’t bear the thought the South had lost, and he took this man’s opinion, along with Davis’s proclamation and the fact that a couple of the Susan Abigail’s crew voluntarily joined the Shenandoah, as proof that the war was not over. Of course the newspapers on the Susan Abigail were three months out of date, as was the captain’s information. Still, without solid proof that the war had ended, and no matter the misgivings Waddell likely had about the prudence of continuing on his present course, he did so with the same grim and unfaltering determination that had gotten him that far. And that proved to be disastrous for the Arctic whaling fleet.

The Shenandoah sailed North, and on June 25, 1865, burned the General Williams of New London. Two days later, on a beautiful and serene day, the Shenandoah made good use of its steam power to capture three more whaleships, the William C. Nye, the Nimrod, and the Catherine, all of which were essentially immobilized due to the lack of wind. Like Ebenezer Nye of the Abigail, Capt. James M. Clark of the Nimrod was no stranger to Confederate cruisers. Two years earlier, when he was captain of the Ocean Rover, his ship had been captured and burned by the Alabama. At that time the first Confederate officer to board his ship was Lt. S. Smith Lee, and now the first person from the Shenandoah to board the Nimrod was the very same Lieutenant Lee, who seemed to regard the coincidence as “an excellent joke,” a sentiment most definitely not shared by Clark.59

There was now “a much larger delegation of Yankees than we cared to have on board,” according to Hunt, “with nothing to do but plot mischief.” So 150 of the whalemen were placed in whaleboats that were strung off the back of the Shenandoah. No sooner had Waddell’s men set fire to their last three captures than the man at the mast spotted five more ships in the distance. “It was a singular scene upon which we now looked out,” remembered Hunt. “Behind us were three blazing ships, wildly drifting amid gigantic fragments of ice; close astern were the twelve whale-boats with their living freight; and ahead of us the five other vessels, now evidently aware of their danger, but seeing no avenue of escape.” Dodging the ice floes, the Shenandoah closed in on the five helpless vessels. Waddell was careful to avoid one of them, which was rumored to have men on board stricken with smallpox, but the other four were fair game, and the Shenandoah managed to catch three of them—the Gypsy, the Isabella, and the General Pike. The Gypsy’s captain was visibly shaken on capture, and according to Hunt, “could scarcely return an articulate answer to any question addressed to him. He evidently imagined he was to be burned with his ship, or at best run up to the yardarm, and could scarcely believe it when I assured him that no personal injury or indignity would come to him.”60 After burning the Gypsy and the Isabella, Waddell ransomed the General Pike for $45,000 to take the Shenandoah’s 222 prisoners back to the States. When the captain of the General Pike wondered aloud how he was going to feed all these prisoners, along with his crew of thirty, during the long voyage back to San Francisco, Waddell told him he could “cook the Kanakas” or Hawaiians, since there were “plenty of them.”61

On June 27 the Shenandoah sighted yet another eleven whaleships in the distance. Waddell wanted to capture all of them, but caution was necessary. The wind had picked up, and if any of those vessels were to become alarmed by the Shenandoah’s arrival, they would undoubtedly attempt to flee, greatly reducing the Shenandoah’s chances of success. So Waddell decided to be patient. The steam engines’ fires were banked, the smokestack was lowered, and the propeller lifted, as the Shenandoah sailed far back from the pack so as not arouse suspicion. Waddell did not have to wait long. The next day the winds died, and the Shenandoah’s steam engine kicked into gear. At ten A.M. the Shenandoah picked off the Waverly, a whaleship out of New Bedford, which was trailing well behind the others, and after transferring the prisoners, burned it. By 1:30 the Shenandoah caught up to the other ten. As Waddell recalled, “The game were collected in East Cape Bay, and the Shenandoah entered the bay under the American flag with a fine pressure of steam on. Every vessel present hoisted the American flag.” The whaleships were gathered closely together because they were trying to render assistance to one of their number, the Brunswick, which had just a few hours before been stove in by a large chunk of ice and was now listing badly, having taken on a considerable amount of water. Soon after the Shenandoah arrived in the bay, a boat from the Brunswick came alongside, ignorant of the Shenandoah’s true identity, and asked for help. Waddell replied, “We are very busy now, but in a little while we will attend to you,” and that they would.62

Once Waddell had the Shenandoah in a good strategic position, he hoisted the Confederate flag and shot off a blank cartridge to announce formally the turn of events. “All was now consternation,” wrote Hunt. “On every deck we could see excited groups gathering, gazing anxiously at the perfidious stranger, and then glancing wistfully aloft where their sails hung idly in the still air. But look where they would, there was no avenue of escape. The wind, so long their faithful coadjutor, had turned traitor, and left them, like stranded whales, to the mercy of the first enemy.”63 All the whaleships lowered their colors and immediately surrendered, with one exception. The Favorite of Fairhaven kept its flag flying, and when one of the Shenandoah’s boats got near, it was clear why. There, standing on the deck, armed with whaling gun and a revolver, was the Favorite’s captain, Thomas G. Young, along with a couple of crew members, who were also armed. Young’s courage, although not his wisdom, apparently had been amplified by a heavy dose of liquor. When the Shenandoah’s boat came alongside, Young yelled, with an odd questioning tone, “Boat ahoy?”

“Ahoy!”

“Who are you, and what do you want?”

“We come to inform you that your vessel is a prize to the Confederate Steamer Shenandoah.”

“I’ll be damned if she is, at least just yet, and now keep off or I’ll fire into you.”64

The Shenandoah’s boarding party reported to Waddell what had transpired, and he called them back to the ship. Young would have to deal directly with Waddell, who ordered his men to steam toward the Favorite. In the meantime Young’s crew, who had begun to “get shaky in the knees” at the prospect of tangling with the Shenandoah, removed the firing caps from the captain’s guns and took all his ammunition, and then lowered themselves and the whaleboats into the water, leaving Young alone on the ship. As Young, who was more than sixty years old, watched the Shenandoah approach, he became stoic about the possibility of literally going down with his ship. “I have only four or five years to live anyway,” he thought to himself, “and I might as well die now as any time, especially as all I have is invested in my vessel, and if I lose that I will have to go home penniless and die a pauper.”65 When the Shenandoah had come within hailing range of the Favorite, the officer of the deck called to Young, “Haul down your flag!”

“Haul it down yourself! God Damn you! If you think it will be good for your constitution.”

“If you don’t haul it down we’ll blow you out of the water in five minutes.”

“Blow away, my buck, but may I be eternally blasted if I haul down that flag for any cussed Confederate pirate that ever floated.”66

This display of bravado amused Waddell, and with grudging respect for Young’s sheer audacity, he sent an armed contingent onto the Favorite to capture Young, rather than fire on the ship at close range. As the Confederate boarding party made its approach, Young attempted to fire the whaling gun, and when he discovered that its caps were missing, he lowered his weapon and surrendered. When Young boarded the Shenandoah, recalled Hunt, “it was evident that he had been seeking spirituous consolation, indeed to be plain about it, he was at least three sheets to the wind, but by general consent he was voted to be the bravest and most resolute man we captured during our cruise.”67

Of the ten vessels cornered in East Cape Bay, eight were burned, including the Hillman, Nassau, Isaac Howland, Brunswick, Martha 2d, Congress 2d, Favorite, and the Covington. This blaze created a scene that Hunt described as one “never to be forgotten by any who beheld it. The red glare from the…vessels shone far and wide over the drifting ice of those savage seas; the crackling of the fire as it made its devouring way through each doomed ship, fell on the still air like upbraiding voices.”68 The remaining vessels, the Nile and the James Maury, were ransomed and sent to San Francisco with all the prisoners on board. There was, however, one passenger on the James Maury who technically didn’t qualify as a prisoner. Before the Shenandoah had appeared, the captain of the James Maury, who had brought along his wife and three children, died. Rather than bury her husband at sea, the wife had him preserved in a whiskey cask for the journey home.

WADDELL NOW HEADED NORTH through the Bering Strait. He knew there were more whaleships in that direction, and he wanted to catch them if possible. But in less than a day of sailing Waddell turned around and headed south. There were, he later wrote, two reasons for this about-face. First, because it was getting colder and there were so many ice floes, he worried about “the danger of being shut up in the Arctic Ocean for several months.” He was also concerned that, if word had gotten out about his exploits, enemy warships would soon be coming for him, and “it would have been easy for them to blockade the Shenandoah and force her into action.”69 According to whaling historian John Bockstoce, “neither of these…[reasons] is convincing.”70 Instead he argues that the newspapers that Waddell captured from his prizes were actually of more recent vintage than he had admitted in his diary of the events, and that, as a result, Waddell knew that the war was virtually over. Thus his decision to head south had less to do with escaping the elements or enemy cruisers than it did with wanting to learn more about the status of the war. Whichever explanation is closer to the truth, by August 2 the Shenandoah was off the coast of California, when it spotted a ship in the distance and gave chase.

It was the British bark Barracouta, on its way to Liverpool from San Francisco. Waddell dispatched a boat to inquire about the news, and when it returned, the news couldn’t have been worse. The Union had indisputably won. “The Southern cause,” wrote Hunt, “was lost,—hopelessly—irretrievably—and the war ended. Our gallant generals, one after another, had been forced to surrender the armies they had so often led to victory. State after State had been overrun and occupied by the countless myriads of our enemies, until star by star the galaxy of our flag had faded, and the Southern Confederacy had ceased to exist.”71 Waddell was stunned. “My life had been checkered from the dawn of my naval career,” he wrote, “and I had believed myself schooled to every sort of disappointment, but the dreadful issue of that sanguinary struggle was the bitterest blow.”72

The Shenandoah’s career as a Confederate raider was over. Waddell and his men had captured thirty-eight ships and 1,053 prisoners. The thirty-two ships that the Shenandoah destroyed were valued at nearly $1.4 million; and of those thirty-two, twenty-five were whaleships. But it was all for naught. The Shenandoah’s actions had absolutely no impact, other than psychological, on the course of the war, which had ended well before the most destructive phase of the Shenandoah’s cruise had even begun. Now Waddell had to decide what to do. From the Barracouta he had learned not only that the South had lost but also that he and his men had been branded pirates and traitors by President Andrew Johnson’s administration and that U.S. Navy warships had been sent to hunt him down. Rather than submit to what he knew would be particularly harsh treatment should the Shenandoah run into an American port, Waddell set a course for England, where he assumed, as Bulloch later wrote, that he would “receive impartial consideration and a fair, equitable hearing” from the government and the courts.73 So as to avoid arousing suspicion during the Shenandoah’s long journey, Waddell stripped the decks and the crew of arms, placing them below, planked over the gun ports, and lowered the steam engine’s stack, trying as best he could to make the Shenandoah look like nothing more than a fine merchant ship going about its business.74

Meanwhile word of the tragedy that befell the Northern fleet had begun to spread.75 Bold headlines in Northern newspapers and firsthand accounts from the Shenandoah’s prisoners heralded the calamity:

THE PIRATE SHENANDOAH

HER CRUISE IN THE ARCTIC SEAS—

WHOLESALE DESTRUCTION

OF AMERICAN WHALERS76

The greatest outcry and the deepest grief emanated from the staunch Yankee port of New Bedford, from which most of the burned vessels hailed. The editors of one of the local papers, the Republican Standard, bemoaned the failure of the American government to come to the aid of the whaling fleet at this time of its direst need. “It seems,” the editors complained, “that there has been gross negligence on the part of the government, in leaving so important of a branch of national industry and so much property without adequate protection. One or two powerful steamers should have been cruising in the North Pacific ever since we had reason to apprehend the depredations by Confederate cruisers.”77

After traveling seventeen thousand miles without a single stop for provisions, the Shenandoah arrived in England on November 5, to an extremely chilly reception. As one London paper put it, “The reappearance of the Shenandoah in British waters is an untoward and unwelcome event. When we last heard of this notorious cruiser she was engaged in a pitiless raid upon American whalers in the North Pacific…. It is much to be regretted…that no federal man-of-war succeeded in capturing the Shenandoah before she cast herself, as it were, upon our mercy.”78 The Shenandoah’s return fanned the flames of American anger over Britain’s duplicitous role in building and outfitting Confederate raiders, while at the same time it mortified the British politicians and their constituents, who knew that America’s anger was partly, if not wholly, justified. There followed a few tense days of detention during which the men of the Shenandoah waited to hear news of their fate. Then, much to their surprise and great relief, they were set free. The British government had concluded that it had neither the grounds nor the desire for pursuing any form of prosecution. The Shenandoah was handed over to the U.S. consul, and the men who had sailed her went their separate ways. The surrender of the Shenandoah, however, was not the end of the story. Instead of forgetting about Britain’s role in the launching of the Alabama, the Shenandoah, and a third raider, the Florida, the American government demanded that Britain pay reparations for the damages that these ships inflicted on Northern shipping during and after the war. An international tribunal ultimately arbitrated these “Alabama claims,” and the United States was awarded $15.5 million in gold.79

As for Waddell, he stayed ten years in England and then moved to Hawaii to take command of a mail ship that ran between Yokohama and San Francisco, finally settling in Annapolis, where, after a brief stint as an oyster warden, he died in 1886.80 Until the end Waddell never wavered from his conviction that the Shenandoah had pursued a noble cause in a noble fashion. As he wrote in his memoir, “She was the only vessel which carried the flag of the South around the world…. The last gun in defense of the South was fired from her deck…. She ran a distance of 58,000 miles and met with no serious injury during a cruise of thirteen months…. Her anchors were on her bows for eight months. She never abandoned a chase and was second to no other cruiser, not excepting the celebrated Alabama. I claim for her officers and men a triumph over their enemies and over every other obstacle which they encountered.”81

The Shenandoah’s return to England brought to a close one of the most dramatic chapters in the history of American whaling. The sinking of the Stone Fleet and the depredations of Confederate raiders combined to destroy more than eighty whaleships, and the war itself had caused a serious disruption and hobbled the industry. If history repeated itself, then whaling would rise again, as it had after the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812, when American whalemen rebounded from near destruction to grow again into a major national and international commercial force. But the Industrial Revolution had changed the American landscape so profoundly and irrevocably that history no longer served as a useful guide. The dissolution of the American whaling industry would be further accelerated by a competing source of energy that would soon render the Yankee whaleship a historical relic.