CHAPTER 7

MTQ: MATERIAL, TIME, QUALITY

Every chess player is familiar with the concepts of material, time, and quality. The balance among these three factors is the foundation of every move in chess—and in every decision we make. Making a correct evaluation— and then a correct decision—requires understanding the trade-offs and relative values of these core elements. Material describes our tangible assets. Time is how long it takes to achieve a specific objective. Quality, the most important element and a goal unto itself, is value—or even power. We strive to gain in every area and also to invest and balance the factors correctly.

It was a curious experience when I first tried to think seriously about what exactly goes through my mind when I look at a chess position. After a lifetime of living and breathing the game, I can only compare it to trying to understand what happens in your brain as you read this book. For me, chess is a language, and if it’s not my native tongue, it is one I learned via the immersion method at a young age. Like a native English speaker trying to explain the difference between that and which, such familiarity makes it difficult for me to consider my approach to the game objectively. Now that I’m removed from the heat of battle and tournament play, I can look back at my games and performances with greater introspection and better understand what goes into strategic assessment.

Improving your decision-making is like studying your native language. Even though most of us don’t know much about the mechanics of the language we learned as children, that doesn’t prevent us from speaking it fluently. But still, we all make mistakes: incorrect grammar, words we use improperly, awkward sentences. Millions of books on more effective writing are sold every year to native speakers who recognize the value of communicating with greater precision. Similarly, with decision-making we all have an apparatus that gets us through life. But there are still improvements that can (or is it may?) be made.

To do so requires conscious thought about something you’ve done unconsciously all your life. Since the day you started to crawl, you’ve been making countless choices, and like the rest of us, you’ve developed systems and tendencies that you employ instantly, constantly, without being the least bit conscious of them.

We aren’t going to overturn a lifetime of experience, nor would we want to. We need to start out by becoming aware of the processes that work for us, then move on to improving them step by step. What bad habits have you picked up in your decision-making? Which steps do you skip and which do you overemphasize? Do your poor decisions tend to stem from bad information, poor evaluation, incorrect calculation, or a combination of these things?

Material, the Fundamental Element

Few of us will ever lead a multinational corporation or run in a national election, but all of our routine daily decisions benefit from an improved process. The key to that is the ability to correctly assess and evaluate a situation. By becoming more aware of all the elements, all the factors in play, we train ourselves to think strategically, or as we say in chess, positionally.

Evaluating a position goes well beyond looking for the best move. The move is only the result, the product of an equation that must first be imagined and developed. So, determine the relevant factors, measure them, and, most critically, determine the optimal balance among them. Before you can begin your search for the keys to a position, you have to perform this basic due diligence. We can categorize these factors into three groups: material, time, and quality.

The simplest and perhaps most important area to evaluate is material. Assets, stock, cash, goods, pieces and pawns, it’s all material. In chess, the first thing we do when we look at the board is count the pieces. How many pawns, how many knights and rooks? Do I have more or less material than my opponent?

When we first learn the game, we are all terrible materialists. We capture as many enemy pieces as we can without paying much attention to other factors. A game between two beginners can look more like Pac-Man than chess as the two competitors gobble up each other’s pieces. This is a normal and healthy way to start out. Being told the values is one thing, but only experience really teaches you what those values signify in the “real world” of chess.

In other areas too, most of our objective measurements of success and failure come down to material. On a basic personal level, that means food, water, and shelter. Now that we as a society can express value electronically, it might be an account balance, or stocks or funds in banks. In warfare it’s which side has more soldiers, more guns, more ships. In business it’s factories, employees, stock, cash on hand.

It isn’t always easy to assess the true value of material. We all have personal attachments to certain assets that have little to do with their objective value. These sentimental attachments can distort your evaluation ability considerably, if not always in a harmful way.

When I was a child, my favorite piece was the bishop, for no reason I can remember today. Even in my earliest games I was a great believer in the power of the bishop, and I avoided their exchange at all cost, a habit that often proved detrimental. Other beginners might be attracted to the unusual leaping ability of the knight or, alternatively, develop a fear of this most unpredictable piece.

A significant part of Botvinnik’s intensive research of his opponents was dedicated to discovering such biases in their play. He would comb through their games looking for errors, then try to categorize them in a way he could later exploit. In his teachings Botvinnik made it clear that the worst type of mistake was one produced due to a bad habit because it made you predictable.

Our friends, colleagues, and family usually know much more about our bad habits than we do. Hearing about these psychological tics can be as surprising as being told by your spouse that you snore. Prejudices and preferences in your decisions are unlikely to be harmful as long as you are aware of them and actively work to iron them out. Awareness can mean the difference between a harmless habit and a bias that leads to a dangerous loss of objectivity.

It doesn’t take long in chess or any other pursuit to realize that there is much more to life than material. The first time you are checkmated despite having a big material advantage, you’ve learned an important lesson. The ultimate value of the king trumps everything else on the board, and your value system begins to adjust. You realize that other factors can be even more important.

Anyone who has ever worked for an hourly wage knows that in the most basic sense time has value. Your employer exchanges material—money— for labor, as measured by the hours you work. This is “clock time,” measured and understood in the same way everywhere. It is quite different from what chess players call “board time,” which is the number of steps it takes to accomplish an objective.

Chess players are used to thinking of both types of time during a game. Your clock is ticking and you have a limited amount of time to make all your moves: clock time. Then you have the game itself, where time is divided neatly into moves, alternating between you and your opponent. How many moves does it take to get from point A to point B? How long will it take for my knight to threaten his queen? Can I reach my objective before my opponent reaches his? That is board time. And as I hope to show, success in every kind of enterprise requires the ability to understand and use both sorts of time to your advantage.

The simplest way to demonstrate this is to look at the difference between playing white and black. White goes first, putting him a single move ahead at the start, giving him an advantage in board time. It is a matter of historical debate whether the advantage of the first move should prove enough to force a win for white if both sides play perfectly. As humans we are so far from perfect that this can never be proven. Among amateurs, who are more likely to make errors and wasteful moves, the narrow advantage of that single move at the start is rarely decisive. But among professionals, being one move ahead is a tangible plus. With precise play, that single move allows white to apply pressure and make threats against black’s position. White is acting, black is reacting. Statistics bear out the value of the first move: at the Grandmaster level white wins twenty-nine percent of the time, black eighteen percent, and fifty-three percent of games are drawn. But if white takes too long to decide his moves, he can find himself rushing decisions at the end of the game to avoid defaulting—that is, he might squander his advantage in board time due to a disadvantage in clock time.

A military commander is used to thinking of time in the same way as a chess player, but in the real world things are much more dynamic. There is practically no limit to the number of “moves” you and your enemies can make at the same time. Multiple attacks and counterattacks can take place concurrently around the battlefield, or around the world. But the definition of time remains the same because in both cases what matters is how quickly an objective can be achieved, whether it be on the battlefield or the chessboard.

Time is not gained just by moving faster or by taking shortcuts. Time can often be bought or swapped for material assets. Think of it as paying extra money (material) for express delivery (time). Time for material is the first of the trade-offs in our evaluation system. When is it worth material to achieve an objective, and how much material to invest? How do we know we are getting our “material’s worth” in time?

No one understood the value of time and material better than Mikhail Tal. The first time I saw Tal in person, I was ten years old, and while his year as world champion had come and gone before I was born, his thrilling games were the favorite of every schoolboy. Tal was the ultimate “time player.” When his attacking genius was in full flight, his pieces seemed to move not just better but somehow faster than his opponent’s. How was this possible? The young Tal cared much less for material than most players and would happily give up almost any number of pawns and pieces in exchange for more time to bring his other forces into action against the enemy king. He constantly pushed his opponents onto the defensive, leading to errors and disaster. This sounds simple, but few have been able to imitate Tal’s unique gift for knowing just how far he could go, and few would dare give up as much material as he would.

It’s easy to see that when you’re attacking, being a move ahead is more important than material. But how much more important? Is one move worth two pawns? Or two moves worth a bishop? There is no simple value chart for time, only case-by-case evaluation. Ask a general if he would rather have another company of men or an extra few days. During peacetime he’d rather have the men, while in a guerrilla combat situation the extra time could be much more valuable.

In chess we talk about open positions and closed positions. An open position has many clear lines for your pieces, more options to move in different directions, and more opportunities for attack and counterattack. A closed position usually means a slow, strategic maneuvering game, the chess equivalent of trench warfare. In an open game the value of a move is much greater than in a closed game because a single attack can do much more damage. If the position is blocked and there is little activity overall, there is less need for speed.

These factors occur in business as well. Imagine that you own a company that is working on a new product line. You know a competitor is working on a similar project and is at around the same stage in development. Should you rush your products to market to beat Company B? Or should you spend more money on development to try to ensure your product is superior to Company B’s? Of course the answers always depend on real-world factors, so recognizing what sort of situation we are in is a crucial part of the evaluation. Before you start considering trade-offs, take a good look around. What industry are these companies in? What type of product is it? Time is always a factor, but is it really of the essence in this case, or are you just being impatient? Putting a new heart medicine on the market isn’t the same as trying to get the latest gadget out in time for Christmas shoppers. What’s important is recognizing the exchange between time and material.

My third world championship match with Anatoly Karpov presents a wonderfully clear example of this constant fluctuation. It was the eighth game of our 1986 match, which was split between London and Leningrad, as St. Petersburg was still known at the time. Searching for an advantage, I offered Karpov a pawn in exchange for the opportunity to attack his king, judging that the two moves I would gain against his king were worth the price of a pawn on the other side of the board.

Karpov had done the same math, and after his evaluation he captured the pawn. My attack quickly built up steam until it was Karpov’s turn to offer material in order to organize a defense of his king. He exposed his rook to my bishop; taking it would give me a slight material advantage, but at the cost of abandoning my attack and allowing him to consolidate his position. This was a classic example of the fluidity in the factors of material and time as they played a role in both of our games. I gave up material for attacking time, and later Karpov offered the material back to gain time for his defense.

I declined the offer, not wanting to go from lender to borrower so quickly. (It’s worth noting that Karpov, as a matter of style, would certainly have taken the material had our positions been reversed. Taking the rook guaranteed a small advantage with no risk, exactly the sort of situation Karpov enjoyed.) I ignored the rook and instead continued on, down a pawn, looking for a way to break through. A few moves later I even gave up another pawn to keep my attack alive, even though this meant I was likely to lose if my attack didn’t succeed. As so often happens, an advantage in board time—pressure and threats that force your opponent to react— results in an advantage in clock time. Move after move, Karpov had to burn a lot of time finding his way through all the dangers to his king. With ten moves still to go until we got more time added to our clocks, Karpov lost on time, a nearly unprecedented event in his long career.

This game serves as a testament to my philosophy of preferring time over material, favoring dynamic factors over static factors. These evaluation preferences are part of one’s style and aren’t necessarily superior or inferior to those of others, only different. Karpov lost that game; does that mean he was wrong in his evaluation of the position? Or that I was right? Neither. In another situation, material might have triumphed over time. What’s important here is to recognize these factors at play.

Each piece in chess has a standard value that allows us to quickly add up who’s ahead in the arms race. Our standard of measurement, our basic currency, is the pawn. Each player starts with eight of these foot soldiers, the most limited and least valuable members of the army. Even the word pawn has come to connote weakness and expendability. We even say “pawns and pieces,” not including them in the same class as bishops, knights, and rooks.

Pawns provide a useful system of equivalent value. Knights and bishops are said to be worth three pawns. Rooks are five pawns, while the queen is worth nine. (The king, whose capture ends the game, is weak but priceless.) So informed, a beginner can go into battle knowing that he shouldn’t give up a knight for a pawn, or a rook for a knight.

But for the experienced player, much more goes into the evaluation of a position than counting pieces and moves. The piece values fluctuate depending on your position and can change after every turn. The same is true about the value of a move, unless we believe Tal’s knights really were faster. Material is the fundamental reference point; time is movement and action. To be correctly understood and utilized the two elements must be governed by a third element: quality.

Generations of platitudes teach us that there is good money and bad. There is even the entrenched notion of “quality time.” In chess we talk about a weak knight or a particularly strong pawn, because their value changes depending on their placement and on other factors. A knight located in the center of the board—where it controls more territory and can join the fight in any region—is almost always more valuable than one near the edge of the board, a concept that is immortalized in the old chess maxim “A knight on the rim is dim.”

On the real field of battle as well, all terrain is not equally valued. Throughout the history of warfare combatants have sought the highest ground available. From the heights your archers, and later your artillery, can shoot farther and your commanders can better see the battle develop. Satellites and airpower have changed these ancient equations in many ways, but it will always be true that where your forces are placed can be as important as their strength in numbers. Placement provides, or limits, utility, which is what the commander—or the business executive or the chess player—seeks.

We often talk about having a “good” bishop or a “bad” bishop, and understanding how this can be provides insight into the subtle but essential differences in the materials that we work with every day. My childhood favorite, the bishop—called an elephant in Russian and a fool in French— is a good example because of the way its movement is limited. The bishop can travel as many squares as it likes in any diagonal direction, but on only one color of the board. This gives it great range but makes it predictable. If many of the squares of the bishop’s color are occupied by pawns of the same color, its mobility is extremely limited.

Such a bishop is called bad, but its intrinsic nature is no different from when the game started. Its quality has been diminished by the circumstances around it. From a practical standpoint, that of utility, it is inferior and should be considered as such. If I have a bad bishop, I would be glad to trade it off for another piece.

The CEO and the general have to be alert to bad pieces in their worlds as well. When Jack Welch took over the behemoth that was General Electric in 1981, one of the first things he did was to make a list of all the divisions in the company that weren’t performing up to his standards. The directors of those operations were told they had to improve or their divisions would be sold or closed down. Instead of hanging on to units solely for their presumed material value, GE would focus on what it was best at and cut back in the areas where it wasn’t doing well.

Any chess master would recognize Welch’s strategy as employing the principle of improving your worst piece. He was applying Tarrasch’s dictum “One badly placed piece makes your whole position bad!” If you have a bad bishop, you try to find a way to activate it, to make it “good.” If it can’t be rehabilitated, you try to swap it off or eliminate it. The same is true of ineffective material in any business or enterprise. Put that bad piece, that underperforming asset, to good use or get rid of it and your overall position will improve.

Returning to our stock portfolios, we can see why the same strategies don’t always apply. Any good investment counselor will tell you to keep a balanced portfolio with a mix of risky and stable assets depending on your age, needs, and income. If you constantly sell the things that aren’t performing well at the moment, you will inevitably be out of position at some point—and it could happen at a crucial juncture when you have everything to lose.

Putting the Elements into Action

Only in extreme cases can material in chess be completely inert and worthless. A knight that is trapped in the corner may someday escape and play a critical role in the fight. One of the difficulties programmers have in improving computer chess programs is the “concept of never” and how it relates to the value of material. Even a weak human player can see that a piece has permanently been trapped and is therefore worthless. But to a computer that piece still has the same numeric value in its calculations as before it was trapped. Perhaps some points are deducted for loss of mobility, but there is no good way to teach a computer that a bishop on square X is worth three pawns but on square Y it’s only worth one.

This gives us different classes of material: long-term and dynamic. Investment portfolios work much the same way. Depending on personal style and needs, your portfolio might be full of dynamic (liquid) assets, which require constant attention and reassessment. Or the portfolio might be aimed at long-term growth and preservation of capital (bonds) for a retirement that is still decades off. My play in the aforementioned game with Karpov showed my preference for dynamism and his for the long term. I sacrificed pawns to make my remaining material more valuable in the short run. Had my attack failed, his investment in long-term material advantages would have won the day.

This was a typical theme of many of my games against Karpov thanks to our different natures regarding time and material. In our first world championship match my skills were not so well developed, and Karpov’s material advantage deflected my attacks. His evaluations were superior. But by the London match, a year and a half later, I had learned to be less rash with giving away material, and it was a different story.

“Who is winning?” is a simple enough question, but real evaluation is a complex undertaking. First we count material. If one player has a significant advantage here, we can say he is winning unless his opponent has compensation in time and/or quality. Whose forces are better developed and placed more aggressively? How quickly can one side attack and the other defend? How long will it take for reinforcements to arrive? Who commands more territory? Is someone’s king in danger? These are all qualitative evaluations, and each carries a different degree of significance.

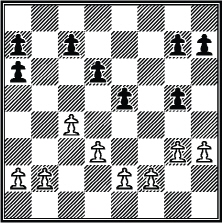

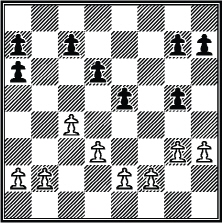

One way to illustrate the relative nature of qualitative evaluations— the type that leaders in every enterprise must do each day—is to examine the qualities of a group of pawns on a chessboard. A chess visual aid will help us here (you don’t even need to know how to move the pieces).

Take a look at the difference between the white and black pawns in the diagram. Both sides have the full contingent of eight, so they are equal in material. The qualitative difference here is structure, the form the pawns take as a group. White’s are orderly and form a complete wall across the board. Black’s are fragmented into three “islands.” In two cases, one black pawn stands in front of another, limiting its mobility. Thus we would say that white has a “superior pawn structure.”

In that we would be correct, and the game would be simple if there were no pieces or kings. But in a real game, the pawn structure would be just one factor in evaluating the position. The holes between the black pawns could possibly benefit black, giving him compensation for his inferior structure. A chess player who likes long-term static advantages such as a solid structure would undoubtedly prefer to play the white side. But show such a position to the great David Bronstein, who challenged Botvinnik for the world title in 1951, and he would surely prefer black! Like me, Bronstein was a dynamic player who always favored short-term activity over long-term considerations. Here he would be content to have those structural holes because he would use them to activate his pieces. I tend to look at structure in chess as a double-edged sword; it can cut both ways, depending on what kind of player you are. Only the truly accomplished strategist will be able to see how—and why—the concept of structure works this way in the situations he faces every day.

Finer, double-edged factors such as structure come into focus only when the forces are evenly matched in the essential areas. The stronger the players, and the more balanced the game, the more the evaluation comes down to the tiniest details. While major differences in material and time are relatively obvious, distinctions in these more subtle criteria only show under great pressure, and it is the mark of a great player to be able to detect and exploit them. The saying goes that the “devil is in the details,” and these secondary factors are the chess player’s devils. Any police officer can follow a thief’s footsteps in the snow, but Sherlock Holmes could deduce an amazing amount from clues invisible to others.

What are the smaller issues that can have a big impact on our lives? Few of us need to worry about food and water, yet we obsess over material things as much as our ancestors. The higher concepts of utility, quality, and happiness sound too vague and philosophical to think about. We think about time as something not to waste, not as something to invest.

Our pursuit of education provides an elegant rebuttal to that idea. What is going to college if not an investment of material and time for quality? We give time and money to gain skills that will raise our intrinsic value to an employer. Higher education is one way we (or our parents) make material sacrifices to increase the quality of our position in the future. The more we can afford to invest, the greater our return will be. If you have the money and grades to go to a top university, you will be able to gain a superior education, make better contacts, and be better positioned to enter the job market.

Perhaps a more openly mercenary path, getting an MBA, offers a clearer example. An executive making a hundred thousand dollars a year decides to leave a good job and spend tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars to go back to school. By all accounts, going to business school isn’t much fun, so short-term enjoyment isn’t a motive. Considering the investment of time and material, the qualitative return must be judged to be high since business school enrollments continue to rise.

That return in quality comes in the shape of skills and contacts, which then lead to a better job. Higher pay and more responsibility enhance the new MBA’s quality of life, or at least that’s the way the formula is supposed to work. Certainly, many people with business degrees are unhappy. A new high-paying job might take up so much time that none is left for activities that are significant components of happiness. The difficulty is in being aware of these small factors and evaluating them before we make a decision that affects them.

The questions we must ask are not only about trade-offs. Giving up material doesn’t always result in a gain of time, or vice versa. At least in chess, you can have it all or lose it all. The player with a winning position will usually have more pieces and be ahead in time and have superior placement and position. Consider this the “rich grow richer” variation.

A politician on the campaign trail is seeking happiness by way of winning the election. The candidate has a limited amount of time and a limited amount of money. His strategy is predicated on using these things to give the biggest possible boost to his image in the eyes of the electorate. Although a huge amount of money is spent on campaigns, now more than ever, experience shows that subtle elements can still surprise. A single sound bite or gaffe can shift perception dramatically, for better or for worse. Dan Quayle’s mangling of the spelling of the word potato in front of a classroom full of kids while on the campaign trail mangled his political career forever. However, such things only rarely overcome more fundamental advantages and disadvantages.

These exchanges between material, time, and quality are just as powerful in our personal lives. For example, my wife, Dasha, and I recently bought a new home, an ordeal that for me involved no fewer considerations— and no less stress—than playing in a world championship match. Anyone who has bought a home or even rented an apartment knows how many trade-offs are involved. They go well beyond the obvious one of material vs. quality. Even if you believe that “you get what you pay for” and the more you pay the better house you’ll get, figuring out precisely what “better” means is complex, especially if you have a family, which increases the number of decisions and the number of decision-makers.

The same cliché rules in both real estate and chess: “location, location, location.” Where you live is as important as what you live in. If you have children, you’ll want to be near a school; if you work long hours, you’ll want to be near your office. In any case, you’ll want a neighborhood that’s safe, convenient to shopping and entertainment, and so on. These are the obvious qualities people look for. We have equivalent guidelines in chess too. “Play in the center.” “Get your king to safety quickly.” These rules of thumb serve as useful guides for beginners. But as players advance, they begin to detect the occasional exceptions to the rules, and capitalizing on these exceptions is what separates a great player from a good one.

There is no universal formula for evaluation. We get caught up in standardized rhetoric and end up with something that doesn’t fit our unique needs. For the most part we all know what we like and make decisions accordingly, but under pressure we can easily be confused and lose sight of our goals. The little things are hard to keep in mind when there are so many big things, so it’s no surprise that the “small stuff” causes the most problems.

Many fail by overdependence on the areas they best understand. It is comforting to stick to what you know, and you are often unaware that a problem can be seen from a different perspective. If you are so focused on just one aspect of a situation—if you fall blindly in love with your bishops, or that corner office, or that big tree in the backyard—you will almost certainly make mistakes in your evaluation.

While you can “have it all” in chess, and perhaps even in life, that elysian condition is not useful for learning. Most of the time we will have to balance, exchange, and evaluate over and over. If we do this well enough to blend material, time, and quality into a multidimensional evaluation, we gain a clear idea of what we want and can then plan on how to achieve it. When we see all the factors, we can then learn how to shift them and build them. Without expanding our powers of evaluation we risk fulfilling Oscar Wilde’s famous observation about knowing “the price of everything and the value of nothing.”

Material is only as valuable as the use it can be put to. Time for action is only important if it helps us make our material more useful. Most people would welcome having an extra hour in the day, but not the man in a jail cell. The message here is, use time to improve your material, not just acquire more of it. Material for its own sake is as useless as wasted time in the pursuit of our goals.

Useful material and well-spent time lead to winning in a chess game. In the corporate world they lead to higher revenues. In war and politics they lead to victory. And I might add that in everyday life, “victory” can simplistically, perhaps a little romantically, be defined as happiness. Money can’t buy it, after all. But I believe that by using your time wisely you can put all your material to your best advantage and achieve the ultimate goal of quality. That’s the promise of the material-time-quality concept—in chess and in life.