CHAPTER 3

HOW TO CRAFT A GOSPEL PRESENTATION

Scratch where they itch.

Jim was born in a small town in Iowa in the 1950s. He grew up going to church, attending Sunday school, and learning all the stories about Moses, Jonah, and Jesus. In the 1970s, Jim moved away from home to go to college in San Francisco. This was a time of experimentation for him as he explored drugs and sex and developed a new set of friends. He left behind the Christianity that he had inherited from his parents. But after a few years, he found his new lifestyle unsustainable. The drugs affected his ability to hold a steady job. Casual sex made him feel more lonely. And his new friends were self-absorbed and tiresome.

One day, Jim walked past a church. It advertised an old-style revival meeting that Saturday night. So he went. And that night Jim heard familiar hymns from his childhood. The Bible passage was also familiar: it was the story of the prodigal son from the book of Luke. Even the preaching style was familiar. A preacher delivered a fiery monologue for twenty to thirty minutes. But it wasn’t the speaking style that gripped Jim; it was the preacher’s message. He heard that he had knowingly disobeyed God, broken God’s laws, and was now guilty. Jim realized that he deserved to be punished for his sins. But he had heard good news as well, that if he trusted and followed Jesus, his sins would be forgiven.

Jim was cut to the heart. After the preacher finished his message, Jim prayed the prayer of repentance and gave his life to Jesus. He felt a huge weight lift as his sins were washed away. That day was a clear line in the sand for him. After that, he considered himself a committed follower of Jesus Christ.

That day was long ago now, and today Jim has been happily married for more than thirty years. He and his wife have one daughter, Megan, who is all grown up and working in a career. However, Megan will have nothing to do with her father’s Christianity. Whenever Jim tries to share how Jesus died for her to take away her guilt, Megan finds the message cold and offensive. For Megan, Christianity is a white man’s organized religion which imposes artificially constructed laws upon people to control them by making them feel guilty.

Jim doesn’t know what to do. When he heard the gospel message all those decades ago, it was so convicting to him. But that same message has no effect on his daughter. If anything, it is turning her away from Christianity.

Many Christians are familiar with one way of understanding and talking about the gospel. They grasp one chief gospel metaphor—in Jim’s case the idea of guilt and forgiveness. But the Bible also gives us several other metaphors that help us understand what Jesus has done for us. In this chapter, we will explore other biblical gospel metaphors which we can use to craft a compelling gospel presentation that speaks to the needs and wants of today’s audience.

HOW DO WE PRESENT THE GOSPEL?

In Acts 16:30, the Philippian jailer, facing a crisis, asks Paul and Silas, “What must I do to be saved?” How would you have answered this question? How would you have presented the gospel to the jailer? And is there only one way to present the gospel, or are there many different ways we can do this? Is there a best way of presenting the gospel? Is there a wrong way?

Let’s say we have a car that we want to give to a friend. But our friend is reluctant to take our car because they are skeptical that it is what they need. How would we promote the car to our friend?

If our friend was an engineer, we would tell them about the engine specifications—the cubic-inch capacity, the number of cylinders, and the double overhead camshaft. If our friend was an architect, we would emphasize the form and beauty of the car: “Look at the teardrop aerodynamic shape!” If our friend was a racecar driver, we would tell them about the car’s performance, the quarter-mile time. If our friend was a sales representative, we would tell them about the trunk space. If our friend was a nurse, we might tell them about the safety features of the car. If our friend was a college student, we might emphasize the car’s economy.

It’s the same car. But we have different ways of promoting it to different people. In none of the cases are we being deceitful. Instead, we’re emphasizing some aspect of the car that our friend will immediately understand. We are also promoting an aspect of the car that will engage our friend at emotional and existential levels.

Conversely, we can unwisely choose an aspect of the car that our friend will not understand. Or we can promote an aspect of the car that will not connect at an emotional or existential level. For example, a racecar driver might not be interested in trunk space. Or an engineer might not be interested in form and beauty. Or a sales representative might not be interested in engine specifications. It’s not that it’s wrong to do it this way. But it might not be the most strategic way because it doesn’t connect.

This is also true when we present the gospel. It’s the same story—God’s story—true for all people, at all times, in all places. But the Bible gives us different ways of explaining it to different audiences and different people. Each audience will have different existential entry points. Each audience will find a different aspect of the gospel that connects emotionally with them. For example, when Jim heard the gospel presentation using the biblical metaphor of guilt and forgiveness, it connected with him existentially and emotionally. But that same biblical metaphor had much less connection with his daughter, Megan. So what other biblical metaphors can we use? How else can Jim try to present the gospel to his daughter? In this chapter we will answer this question by looking at the different gospel presentations in the Bible, different gospel metaphors, and several different contemporary gospel presentations.

GOSPEL PRESENTATIONS IN THE BIBLE

The gospel is true for all people, at all times, in all places. It is the same story—God’s story—for everyone. But at the same time, the different books of the Bible employ different ways of presenting the gospel for its different audiences.

In the gospels of Mark and Matthew, the gospel is God’s story about Jesus—the Messiah, the Son of God. The blessing of the gospel is entry into the kingdom of God. The correct response to the gospel is for the audience to repent, deny themselves, humble themselves, and give up everything to follow Jesus (Mark 1:1; 1:14–15; 4:30–34; 10:14–15; cf. Matt. 4:17; 13:31–35; 18:1–5).

In the Gospel of Luke, the gospel presentation is similar to Mark’s and Matthew’s. Jesus is the Son of God. The blessing of the gospel is entry into the kingdom of God. The correct response is to repent, deny oneself, humble oneself, and give up everything to follow Jesus. But Luke’s implied audience is slightly different. There’s an emphasis on Jesus’ mission to those who are marginalized: for example, the women, the poor, the sick. For this audience, salvation is described as freedom, healing, and restoration.

Luke also shows what the correct response to the gospel looks like for different audiences. Both the expert in the law (Luke 10:25) and the rich young ruler (Luke 18:18) ask Jesus the same question: “What must I do to inherit eternal life?” But Jesus gives a different answer to each person. The expert in the law needs to love like the Samaritan (or be loved by the Samaritan, depending on our interpretation of the parable), while the rich young ruler needs to give up his love of riches.

Luke also gives us the example of Zacchaeus as the paradigm of a true follower. While the rich young ruler is the negative example of someone who can’t give up everything to follow Jesus (Luke 18:22–23), and the Pharisees are the negative example of people who love money (Luke 16:14) and are self-righteous (Luke 16:15; 18:9–12), Zacchaeus is the positive example of someone who can give up self-worth, self-dignity, and riches to follow Jesus joyfully (Luke 19:1–10).

In John’s Gospel, we have the well-known gospel summary of John 3:16–17. John also shows how Jesus himself presents the gospel differently to different people. To a Pharisee—Nicodemus—Jesus says, “You must be born again” (John 3:7). But to a Samaritan woman at a well, Jesus says, “Whoever drinks the water I give them will never thirst” (John 4:14). To a man born blind, Jesus says, “I am the light of the world” (John 9:5). Moreover, we have the “I am” sayings of Jesus, where Jesus chooses a well-known Old Testament metaphor and applies it to himself, but in a way that is contextually relevant: “bread of life” (6:35, 51, 58); “light of the world” (8:12; 9:5); “gate” (10:7, 9); “good shepherd” (10:14); “resurrection and the life” (11:25); “way, truth, and life” (14:6); and “true vine” (15:1, 5). Thus, in John’s presentation of the gospel, Jesus is the Son. The correct response is to believe in Jesus. The blessings of the gospel are eternal life and union with Jesus and other believers.

In the book of Acts, Luke’s summary of the gospel is found in Peter’s speech to the crowd on the day of Pentecost (Acts 2:32–38). Jesus is the exalted Messiah. The blessings are forgiveness of sins, indwelling of the Holy Spirit, and membership in the new people of God. The correct response is to repent and be baptized. But then in the rest of the book of Acts, Luke shows how the apostles present the gospel differently to their different audiences. To the Jewish audiences, the apostles present Jesus as the risen Messiah. They emphasize Jesus’ titles—Son, Messiah, Prince, Savior. They show that Jesus is the fulfillment of Old Testament prophecies. And they use Scripture as a starting point for the conversation. Scripture gives them common ground with their audience. The Scriptures are the epistemological justification for their claims (Acts 4:10–12; 5:29–32; 13:32–41).

But to gentile audiences, the apostles use a different approach. The apostles present Jesus as the one they have been seeking all along. But there is no mention of Jesus as the fulfillment of Old Testament prophecies. There is no mention of Jesus’ titles. There is no mention of Scripture. Instead, the apostles look for common ground in God’s common grace (sending rain, making crops grow, providing food), general revelation (his creation), and the universal human desire to worship a god. They also quote not Scripture but references from their audience’s cultural authors as starting points for the conversation (Acts 14:15–17; 17:22–31).

FINDING COMMON GROUND

I’m not saying that we don’t use Scripture at all when we present the gospel. We need eventually to end up with Scripture, for that is where we get our gospel. But I’m saying we don’t necessarily have to begin with Scripture.

The apostles look for common ground, something that both they and their audiences already hold to be true, as a beginning into the gospel. For a Jewish audience, that common ground was Scripture. But for a gentile audience, unfamiliar with Scripture, the common ground was God’s common grace, general revelation, universal human desires, and their cultural authors.

In Paul’s letters, we can find a handful of representative summaries of Paul’s presentation of the gospel (Rom. 1:1–6; 1:16–17; 2 Cor. 5:20–21). Paul presents Jesus chiefly as the Christ, the Son of God. The blessings of the gospel are justification, sanctification, reconciliation, and union with Christ. The correct response is faith and obedience. But even Paul has a variety of different ways of presenting this same gospel story. For example, I’ve already mentioned in a previous chapter how Paul describes the gospel as God’s gospel (Rom. 1:1), but then he also calls it my gospel (Rom. 16:25). He necessarily tailors it to his audience. I remember hearing Timothy Keller note that Paul says that there is one gospel (Gal. 1:8) but then distinguishes between two different forms of the gospel—“the gospel to the circumcised” and “the gospel to the uncircumcised” (Gal. 2:7; cf. 1 Cor. 1:22–25; 9:19–23). This suggests that Paul was thinking about how to contextualize the message for the different audiences he encountered.

Finally, it’s helpful to notice that every now and then in the New Testament, we get a presentation of the gospel in the form of early traditions, hymns, summaries, and creeds (1 Cor. 15:3–4; Phil. 2:5–11; Rom. 10:9; 1 Cor. 1:23; 1 Tim. 3:16). This reminds us that the message of the gospel was spoken, sung, memorized, summarized, and communicated in a variety of forms.

Every gospel presentation in the Bible essentially says something about Jesus: who he is, what he has done, what he will do. It also says something about the blessings of the gospel, which are both individual and corporate. And then it says something about the correct response to this gospel. It also implies an incorrect response—sinful response—to the gospel, and the condemnation for remaining in sin.

But notice that even in our brief and far from comprehensive survey of the New Testament, there is a wide variety of presentations of the gospel. There are different genres—narratives, speeches, letters, parables, hymns, creeds, traditions, summaries—and different metaphors—Jesus as Son, Shepherd, Bread, Life, Truth, Way, Light, Gate, Vine. There are different blessings. Different styles. Different tones.

There are also different emphases. For example, I heard Timothy Keller point out that the Synoptic Gospels emphasize the entry into the corporate kingdom of God. But John emphasizes the promise of eternal life. And Paul emphasizes justification. The significance for us is that we also should be free to try out different gospel metaphors, looking for the ones that will best connect with our audience at an existential and emotional level.

It also means that it is unfair to criticize a gospel presentation for not mentioning something. Otherwise we’d have to give a comprehensive presentation of all sixty-six books of the Bible and every single biblical metaphor in order to present the gospel. A gospel presentation is a summary of who Jesus is, what blessings are promised to us, and what our response must be. The logical flipside is that it will also communicate what sin and condemnation will look like. But we need to remember that a summary, by necessity, must leave things out. In doing so it can be sharply focused, penetrating, and to the point.

HOW TO CRAFT A GOSPEL PRESENTATION

When we present the gospel, we are doing at least four things.

- Presenting the gospel elements: Jesus (or God), blessings, response, sin, condemnation.

- Using a set of coherent biblical metaphors to organize the elements.

- By necessity, leaving out other biblical metaphors.

- Being sharply focused, penetrating, and to the point.

My PhD supervisor, Graham Cole, helped me to understand how the Bible can give us sets of coherent biblical metaphors. To explain what this means, let’s begin with table 3.1. In the lefthand column, we’ll begin by filling in some biblical metaphors for God. In the other two columns, we’ll fill in the corresponding metaphor for sin (or the sinful state) and the correct response based on that metaphor or aspect of God’s person and nature.

| God | Sin or Sinful State | Correct Response |

| Creator | Idolatry | Worship |

| King | Rebellion | Repentance and submission |

| Holy | Impurity | Purity |

| Judge | Transgression | Righteousness |

| Savior | Self-righteousness | Calling on his name |

| Father | Broken relationship | Becoming a child of God |

| Groom | Unfaithfulness | Faithfulness |

| Shepherd | Wandering | Following |

Table 3.1

This is just an example, and we don’t have to begin with God. We can mix it up. Look what happens if we begin with sin (or the sinful state) in the lefthand column. Now we can fill in the corresponding salvation blessings in the other column (table 3.2).

| Sin or Sinful State | Correct Response | Blessings |

| Transgression, guilt, rebellion, disobedience | Faith and obedience | Justification, forgiveness |

| Falling short | Calling on God’s name | Reconciliation |

| Captivity | Serving Jesus | Redemption, liberation |

| Blindness | Recognizing our blindness | Illumination |

| Deadness | Recognizing our deadness | Regeneration, life |

| Enemy of God | Ceasing our hostilities | Peace, reconciliation |

| Not a child of God | Repentance, returning | Adoption, reconciliation |

| Uncleanness, impurity | Recognizing our uncleanness | Sanctification, purification |

| Separation | Returning | Union |

| Idolatry | Worshiping God | God’s favor |

| Shamefulness | Honoring God | Restoration, face |

| Wandering, erring, going astray | Walking in God’s ways | Being on the correct path, wisdom |

| Wickedness | Godliness | Godly flourishing |

Table 3.2

Or we can use metaphors and titles for Jesus in the lefthand column and fill in the corresponding metaphors for sin (or the sinful state) and our correct responses in the other columns (table 3.3).

| Jesus | Sin or Sinful State | Correct Response |

| Creator | Idolatry | Worship |

| King, Messiah, Christ | Rebellion | Repentance and submission |

| Holy, Priest | Impurity | Purity |

| Judge | Transgression | Righteousness |

| Savior | Self-righteousness | Calling on his name |

| Groom | Unfaithfulness | Faithfulness |

| Shepherd | Wandering | Following |

| Living Water | Thirsting | Drinking |

| Living Bread | Starving | Eating |

| The Way | Wandering | Following |

| The Truth | Falsehood | Believing |

| The Life | Death | Living |

| The Vine | Nonparticipation | Participation, union |

| Light | Blindness | Illumination |

| Word | Deafness | Hearing |

Table 3.3

Or we can use metaphors for Jesus in the lefthand column and fill in the corresponding metaphors for the work of Jesus and what he saves us from (our sinful state) in the other columns (table 3.4).

| Jesus | What Jesus Does | Sinful State |

| King, Messiah, Christ | Rules | Rebellion |

| Savior | Saves | Self-righteousness |

| Priest | Reconciles | Separation and impurity |

| Shepherd | Shepherds | Going astray |

| Servant | Obeys | Disobedience |

| Groom | Loves | Unfaithfulness |

| Word | Reveals God | Ignorance of God |

| The Way | Reveals the way | Lostness |

| The Truth | Reveals the truth | Error |

| The Life | Gives eternal life | Death |

Table 3.4

Or we can use metaphors for Jesus’ atoning work on the cross in the lefthand column and fill in the corresponding metaphors for our sinful state and our salvation blessings in the other columns (table 3.5).

| Jesus’ Atoning Work | Sinful State | Salvation Blessings |

| Penal substitution | Guilt, penalty of death | Innocence |

| Ransom, redemption | Captivity | Freedom |

| Victory | Defeated by Satan, sin, death | Victory over Satan, sin, death |

Table 3.5

WHAT ABOUT OTHER MODELS OF THE ATONEMENT?

I have omitted the moral influence and moral example models of atonement. That’s because they are a fruit of the atonement rather than a means of atonement. We follow Jesus’ example because he has atoned for our sins. But our sins are not atoned for by our following Jesus’ example.

The lists of metaphors in the tables are not exhaustive. There are far more metaphors that we can use. As an exercise, see if you can add more to the lists I’ve given. You could also add a column to the right which identifies the corresponding condemnation from God. Keep in mind that these lists are meant only to help us craft a gospel presentation; we don’t have to use the exact wording or phrases when we talk with people.

Now that we have a set of coherent biblical metaphors, we can use them to present the gospel. For example, if we begin with God as holy, our gospel presentation might go like this: “God is a holy God. But all of us are impure; we are not as good as we should be. So we deserve to be separated from God forever. But if we call on Jesus to save us, Jesus will wash our sins away and make us clean. Now we can come near to God.”

Or if we begin with sin as transgression, our gospel presentation could be, “We have all done things that we know are wrong, and if we break one law, it’s as good as breaking all of God’s laws. We stand guilty before God. We deserve to be punished by him. But if we trust in Jesus’ death for us, God will justify us.”

Or if we begin with Jesus as King, our gospel presentation would have these elements: “God sent Jesus to be our King. But we have all rebelled against Jesus by living our own way. But God calls on us to repent and submit to Jesus. If we do this, we will be forgiven by God instead of being punished by him.”

Or if we begin with Jesus as Word, our gospel presentation might be, “Jesus is the Word because he reveals God to us. Without Jesus we are ignorant of who God is. But now, if we listen to Jesus, we can know God personally because of him.”

Use the tables as a guide to try this out for yourself. As you practice various metaphors and begin to see how they cohere, you will soon notice that your gospel vocabulary will grow as well. You will be able to talk about the Good News in a variety of ways adaptable to different contexts and people.

EXPLORING DIFFERENT METAPHORS FOR SIN AND SALVATION

By exploring a variety of biblical metaphors for God, Jesus, sin, and salvation, we can connect with the emotional and existential needs of our audience. Here are some thoughts on using the different metaphors.

Calling on the Name of the Lord

The metaphor of calling on the name of the Lord as a means for salvation is prominent in the Bible. It begins in Genesis 4:26 and 26:25. Abraham does it (Gen. 12:8; 13:4; 21:33). The psalmists do it (e.g., Ps. 17:6). Paul uses it in Romans 10:13 (citing Joel 2:32). It is a shorthand term for a Christian (2 Tim. 2:22) and the church (1 Cor. 1:2). It is a useful summary for what we need to do to be saved.

Chief Metaphors for Sin

The Old Testament uses more than fifty words for sin. But according to Henri Blocher, the three main metaphors for sin in the Bible are:1

- Transgression: to break a law, commit a crime, rebel

- Falling short: to miss the mark, to be unclean

- Iniquity: to be broken or bent out of shape

Each metaphor speaks differently to where we are. Someone like the prodigal son was guilty of transgression. But the apostle Paul, who was once called Saul, was not breaking laws but keeping them. Paul wouldn’t have seen himself as a transgressor—far from it. Yet despite his religious zeal, Paul fell short of God’s righteousness. And Isaiah, when he stood before the throne of the Lord, was confronted by his iniquity before God.

All three metaphors are complementary. Together they give us a fuller picture of sin. For example, after David commits adultery with Bathsheba, he confesses his sin to God in Psalm 51. David uses all three of these metaphors in his confession: “Blot out my transgressions. Wash away all my iniquity and cleanse me from my [falling short]. For I know my transgressions, and my [falling short] is always before me” (Ps. 51:1–3).

When we share the gospel, one metaphor will often resonate more than the others with the person we’re speaking with. For example, in a modern culture, which is strong on absolutes, people might see their sins as transgressions. But in a postmodern culture, which is strong on community, people might see their sins as falling short. Or in a society which is strongly aware of the prevalance of social injustices, people might see their sins as brokenness.

Theological Components to Sin

There are also three theological components to sin that we must consider:

- Internal: We sin against ourselves; we let ourselves down.

- Horizontal: We sin against someone else.

- Vertical: We sin against God.

For example, when David committed adultery with Bathsheba (2 Samuel 11), he sinned internally. He sinned against himself. He let himself down. He should have known better. He probably should have gone off to war instead of staying at home alone (v. 1). But he also sinned horizontally. He sinned against Bathsheba by seducing her and making her commit adultery. He also murdered her husband, Uriah. And he sinned vertically by breaking God’s laws and falling short of God’s righteous standards.

Ultimately every sin is against God (coram Deo). This is why David eventually confesses, “Against you . . . have I sinned” (Ps. 51:4). Without this vertical component to sin, it’s very hard to explain why God has to punish us or send us to hell. It’s tempting to soften the way we communicate about sin by mentioning only the internal component—“We have let down ourselves”—or the horizontal component—“We have let down our friends.” But if we don’t eventually communicate the vertical component—“We have sinned against God”—it’s going to be hard to explain why we need to be saved by God from his judgment.

At the same time, the internal and horizontal components give us a fuller understanding of sin. There are personal and social consequences for our sin. For example, after David’s sin with Bathsheba, David lost his moral standing with his family. David’s son Amnon raped his half sister, Tamar, and the moral chaos continued with David’s other son, Absalom, killing Amnon and then staging a war against David. This reminds us that our sins aren’t only between us and God. They are not merely things we do in the privacy of our homes. They have personal and social ramifications.

HELL AND THE HOLINESS OF GOD

Part of the problem of hell is that the punishment seems disproportionate to the offence. Apologetically, we often defend hell by explaining that the problem exists because we have too low a view of God’s holiness. If we understood how holy God is, we could understand the magnitude of our sins against God, and then we could understand the need for God to send us to hell.

But another way of explaining it is we have too low a view of humankind. For our sins are also against fellow humans. For example, if I envy or lie or curse or am impatient, I am sinning against a human—horizontally. And according to God, every human is made in his image, and thus every sin against a human is also a sin against God—vertically (James 3:9). God has a much higher view of humans than we do. Whenever God rails in the Old Testament against Israel and the nations because of their sins, often the sins listed are sins against humans—lying, cheating, fraud, violence (Mic. 6:9–12; Amos 1–2)—especially those who are disadvantaged and marginalized. So if we can understand how holy humans are, and that our sins against humans are also sins against God, we can also understand the need for God to send us to hell.

Manifestations of Sin

There are also multiple manifestations of sin:

- Vertical: offence against God, death, judgment

- Horizontal: socioeconomic-political oppression

- Internal: psychological disturbance

The biblical doctrine is that all humans are in a sinful state before God (Rom. 3:10–18; Eph. 2:1–3). Each and every human is guilty, responsible to God, and needs to repent and ask God for forgiveness.

But sin is manifest in many different ways to us—vertically, horizontally, and internally. For example, when the jailer asks Paul and Silas, “What must I do to be saved?” (Acts 16:30), what is he asking to be saved from? Of course he ultimately needs to be saved—vertically—from his guilt before God. But perhaps he is also oppressed—horizontally—by socioeconomic-political evils. As a member of the working-class poor, he will forever be condemned to work in unjust working conditions. Or perhaps he needs to be saved—internally—from his anxiety, insecurity, and depression. So when the jailer asks, “What must I do to be saved?” he might be aware of all three manifestations of sin in his life.

Interestingly, Jesus in Luke 4:18–19—quoting the commissioning of the Servant in Isaiah 61—claims that he has been commissioned by God to bring salvation at all three levels—vertically (“the Lord’s favor”), horizontally (“good news to the poor . . . freedom for the prisoners”), and internally (“recovery of sight for the blind”). This suggests that we might be able to find an existential connection with our audience by addressing the horizontal problem of social evils. Or the internal problem of psychological and physical states. And demonstrating that this is evidence of the foundational vertical problem of our sin and need for salvation by Jesus.

God’s Judgment

There are also three components to God’s judgment:

- Privation of good: We miss out on God and his blessings.

- Separation: We are cast away from the presence of God.

- Punishment: We pay the penalty for our transgressions.

For example, we see all three components in Matthew’s parable of the wedding banquet (Matt. 22:1–14). Those who decline the invitation to the banquet miss out on the feast. That is their punishment. They could have enjoyed God’s blessings, but they choose not to, and God hands them over to their choices. But they are also separated from God and his banquet. They are thrown outside into the “darkness” (v. 13), and they are punished for rejecting the invitation. God is “enraged” and destroys those who refuse the invitation (v. 7). They are cast outside where there is “weeping and gnashing of teeth.”

Once again, if we cast sin only as something internal or horizontal, it’s very hard to explain why we need God’s salvation. If we cast sin only as our “breaking a relationship with God” or “rejecting God,” it’s very hard to explain why God should punish us. If I break up with a friend, I don’t expect them to respond with vengeance. So why should God punish us for breaking our relationship with him? If we cast sin only as our being more or less victims of social evils, it’s hard to understand why we should be punished by God, for why should God blame the victims?

Even though we are allowed a variety of metaphors to explain sin, eventually we will have to explain that there is a vertical component to sin. Eventually, we will have to explain that God’s judgment is more than a privation of good or a separation from him. Ultimately God’s judgment is a form of retributive justice. It is punishment for our wrongs.

Concepts of Sin

Different cultures gravitate to one of these three biblical concepts of sin:2

| Breaking a law | Guilt | We need forgiveness (West). |

| Defilement | Uncleanness | We need cleansing (Middle East). |

| Breaking relationships | Shame | We need restoration (East). |

Each of these concepts is taught in the Bible. And we happily affirm all of them. But different cultures will find that one concept connects more with their moral system at intellectual, emotional, and intuitive levels. For example, one day my friend was talking to a man who was a Muslim and was on his way to the mosque. But this Muslim man had also just cheated on his wife. The man was worried that he hadn’t sufficiently purified himself after sex and would be too defiled to enter the mosque. He wasn’t all that worried about having cheated on his wife or having broken a law. He wasn’t worried about being guilty or having broken a relationship. Instead, he was worried about being unclean.

Using Shame and Dishonor as a Model of Sin

I believe that our Western world, as it becomes more and more postmodern and post-Western, is also moving away from the guilt model of sin. Many people no longer believe in absolutes. They see laws as artificial constructs imposed upon us by oppressive institutions of power such as churches and governments.

This might be a time for us to explore the shame model in the West.3 Using shame will not send us down the pathway to relativism, for shame has both objective and subjective elements. And when we talk about our shame before God, we talk about how we have not lived up to God’s objective standards for us. More and more, I find that talk about shame resonates with Western audiences. For example, in the West, professional athletes—especially men—often get themselves into trouble when they get into fights or drug scandals or are caught cheating on their wives. How do the sports authorities tell these athletes to behave in their public and private lives? Such men don’t care about laws; they’re professional athletes and can do anything they like! They are a law unto themselves. But the authorities have had some success appealing to a code of honor. They tell the sportsmen to behave to avoid “bringing the game into disrepute” and “letting down their teammates.” This is an appeal to shame and honor.

In 2011 there were riots in Vancouver, Canada, after their hockey team lost the Stanley Cup final. People trashed cars, smashed windows, and looted shops. The riots shamed Vancouver, especially because the city had just proudly hosted the 2010 Winter Olympics. After the riots, newspaper headlines screamed, “Shame!” And webpages uploaded photos to name and shame the rioters.

The use of social media has increased this phenomenon, as observed by Jon Ronson in his book So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed.4 And David Brooks, in an op-ed piece in The New York Times, observes that we now live in a “modern shame culture” which can be “unmerciful to those who disagree and to those who don’t fit in.”5 All of this suggests that shame is becoming more prominent in our postmodern society, with its larger emphasis on community and tribal groups. If so, we can utilize it more often in our gospel presentations.6 For example, when I delivered gospel talks to high school students and talked about breaking God’s laws and being rebels against God, I often got vacant looks from them and some rolled their eyes at me. They were thinking, “Here we go again. The church is imposing its oppressive laws on us, taking away our freedoms.” More recently, I’ve been using the language of shame—we have “shamed God,” we have “not been honoring God”—and the room is silent. All eyes are on me. They get it. It’s personal.

I believe this is similar to the approach of the apostles in Acts. When the apostles preached the gospel to the Jews, they appealed to the guilt model of sin. The Jews had the Scriptures and should have known better. But when God sent them the Messiah, they killed him, thus breaking God’s laws. For this they were guilty (Acts 2:14–40; 4:10–12; 5:29–32; 7:51–53; 13:26–41). But when the apostles preached the gospel to the pagans, they appealed to the shame model of sin. The pagans had been enjoying God’s general creation blessings. But they had not been giving thanks to this God. They had not been worshiping him. Thus, they had dishonored God. For this, they needed to repent (Acts 14:15–17; 17:22–31).

In the twentieth century, modern Western culture had more in common with the religious Jews in Acts. It was churched and familiar with the Scriptures. It believed in laws and absolutes. The guilt model worked well. But in the twenty-first century, the postmodern West is postchurched, post-reached, and post-Christian. It has more in common with the unreached pagan culture in Acts. And perhaps the shame model will work better.

Using Defilement as a Model of Sin

It might also be time for us to explore the defilement model in the West. For example, a pastor whose church has a high proportion of women who suffer domestic abuse says that the women feel defiled by what they have suffered. As a result, what attracts them to the gospel is the promise of being purified by Jesus.

I also have a friend who was addicted to methadone for years. One day while on a train, he was disgusted with his own life. He felt defiled by the drugs he was using, and he cried out to God, “If you’re real, show yourself to me.” At that moment, he felt God wash the drugs out of his system. He gave his life to Jesus and has never taken drugs since that day.

I understand that these examples refer to defilement by our own actions and the actions of others. They do not refer to defilement by sin. But if we feel defiled already, then the defilement model of sin will connect more immediately with us. For example, my friend who was addicted to methadone was not so much worried about breaking laws—he had been breaking them all his life—but he was more worried about the corruption of his body by drugs. Defilement and the need for purification made him also long for the truth of the gospel. Defilement and purification also became a redemptive analogy that made the gospel more plausible to him.

Using Brokenness as a Model of Sin

We also find language of brokenness in the Bible when talking about sin. I understand that brokenness is an elastic term, and it can even be misleading. It can be unhelpful in talking about sin for a variety of reasons.7 But at the same time, brokenness as iniquity is a legitimate biblical metaphor for our sin, and the Bible speaks of broken relationships as a metaphor for our sinful state. Brokenness is also a prominent model of sin in shame cultures. And the language of brokenness is readily accepted by our twenty-first-century audiences. So I believe we can cautiously appropriate the language of brokenness for our evangelism.

Broken relationships are a feature of the Genesis 3 postfall curses. The first curse—weeds in the garden—means that our work will be frustrated. The second curse means that childbirth will be fraught with pain, danger, and death. The third curse—“Your desire will be for your husband, and he will rule over you” (Gen. 3:16)—means that human relationships will be dysfunctional, dislocated, and fractured. All relationships will have some level of brokenness. Today in the West, relationships especially will be broken because of our emphasis on individualism, self-absorption, and pursuit of pleasure on our own terms. For example, I have attended several parenting seminars and have been impressed by the large numbers of people who attend. Many parents in the West—including me—need as much help as we can get because we cannot control our children. There is brokenness in our parent-child relationships.

As another example, I went to a seminar run by an Australian psychologist, Stephen Biddulph. Biddulph said that in a room of one hundred Australian men, thirty-three will not have spoken to their fathers in years, maybe decades. Another thirty-three will speak to their fathers, but it ends badly: words are said, someone storms out, and a door is slammed. And the last thirty-three say that they have an okay relationship with their fathers because they catch up once a week for dinner. But that’s duty, not a warm relationship. Biddulph goes on to say that in a room of one hundred Australian men, only one can say that they have a warm functional relationship with their father. Biddulph goes on to propose that to function as husbands and fathers, men need to be reconciled first with their earthly fathers.8

I used this example when I gave a talk to a room full of a hundred powerful businessmen and CEOs. Afterward there was silence. Every set of eyes was locked onto me. Each man was inwardly acknowledging that he had a broken relationship with his father. Despite his success and status, he still had much pain and hurt. His life was broken. I then used this as a redemptive analogy for how our relationships with God, our Father, were also broken, and we need reconciliation. But unlike our earthly fathers, where reconciliation might not be possible, reconciliation with God is possible. And God can be the Father that we never had, but have always needed.

Using Self-Righteousness as a Model of Sin

I have also started using self-righteousness as a metaphor for our sinful state. A twenty-first-century Western audience no longer believes in laws as absolutes. So they don’t feel guilty about having broken any laws. And our Western narrative tells us that we are free to pursue happiness on our own terms. The mantra is to “be true to yourself.” So how can anyone be guilty as long as they are trying to be happy? What can possibly be wrong with being authentic? We are now told that guilt is a social construct imposed upon us by organized religion to rob us of happiness and true identity.

But even with this narrative of freedom to pursue our own happiness, our twenty-first-century Western audience is quite self-righteous. If I am pro-environment, I might recycle, carry my groceries home in a bright-green environmentally friendly shopping bag, and drive a prominently badged hybrid car. And I will feel good about myself because I am doing the right thing. Or to give another example, if I am happily married, with children who attend an elite school, and I mail out Christmas newsletters with an impressive list of achievements each year, I will feel good about myself because I must be doing the right thing.

Correspondingly, the twenty-first-century Western audience is also quite judgmental. If I am doing my thing for the environment, I will look down on those who are not. I might roll my eyes at those who do not recycle properly, use plastic shopping bags, and drive a gas-guzzling SUV. I will feel morally superior to them. As another example, if I am happily married, I will look down on those whose marriages have failed. I might roll my eyes at how their children are not high achievers. I will feel morally superior to them.

Jesus often uses self-righteousness as his chief metaphor for sin, especially in the Synoptic Gospels, and more specifically in the Gospel of Luke. For example, Jesus tells the parable of the Pharisee and tax collector to “some who were confident of their own righteousness and looked down on everyone else” (Luke 18:9). In Luke 18:9–14, the Pharisee’s sin is not that he’s guilty of breaking laws. Instead his sin is self-righteousness, moral superiority, judgmentalism, and looking down on those around him.

Using Idolatry as a Model of Sin

Our Western narrative also tells us to pursue fulfillment. We seek life, happiness, freedom, pleasure, success, identity, status, and security. Believe it or not, these are God-given things for us to enjoy. They are not bad things in and of themselves.

In the parable of the rich fool, Jesus tells us, “The ground of a certain rich man yielded an abundant harvest” (Luke 12:16). This is Jesus’ way of saying that God is the one who gave the man his abundant harvest. God gave this man his success, wealth, and security. So the man’s riches are not a bad thing in and of themselves. They are a good gift from a good God for him to enjoy.

But in the parable, it’s what the man does with God’s gift that is sinful. The man makes his riches his source of security. That’s why he stores his grain, thinking the riches it will bring will guarantee him lifelong happiness: “You have plenty of grain laid up for many years. Take life easy; eat, drink and be merry” (Luke 12:19). He makes his riches do what only God can do: be the source of life, happiness, freedom, pleasure, success, identity, status, and security. Or to use the categories of the Bible, he makes an idol of his gift from God.

In the Western narrative, we do the same thing. God gives us life, freedom, pleasure, success, health, sports, school, work, family, friends, abundant wealth and possessions. But rather than worship God the giver, we worship the gifts. We ask the gifts to do what only God can do for us.

What is wrong with this? The problem is that the gifts can never be God. So we’re asking too much from the gifts. And either we will destroy them or they will destroy us. For example, if I make the trophy family the source of my happiness, I will destroy my spouse and children by asking them to do for me what only God can do. Or I will destroy myself by trying to be the perfect father and husband, which only God can be. As another example, if I make fitness and beauty my source of identity, I will destroy my body by asking it to be what only God can be. Or I will destroy myself in my quest for beauty and perfection, which only God can be.

Author and pastor Timothy Keller, in his sermons and books,9 often uses idolatry as his preferred metaphor when describing sin to a postmodern Western audience. Keller says that we’ve all got to live for something, otherwise we’ve got nothing to live for. But whatever we live for will own us. Whatever we live for will never fulfill us. And whatever we live for will never forgive us when we fail it. We become enslaved to our idols, and they ultimately destroy us.

This is the great irony of our Western narrative. Our Western narrative tells us that we are free to do whatever we want. We are free to pursue happiness on our own terms. This is the foundational premise of the US Declaration of Independence, the French Revolution, and the first line of the Australian national anthem. But the truth is that we are owned by whatever we pursue. We surrender our freedom in our quest for freedom. As Paul says to the Corinthians who glorified their pursuit of freedom, “ ‘I have the right to do anything,’ you say—but not everything is beneficial. ‘I have the right to do anything’—but I will not be mastered by anything” (1 Cor. 6:12). The great paradox in the Bible is that salvation is found in giving up our freedom to pursue happiness on our own terms and worship God instead. In doing so, we will find true freedom.

Using Falling Short as a Model of Sin10

Our Western narrative also tells us to be the best we can be. A prominent catchphrase of the twenty-first-century generation is that we want—actually, we need—to “make a difference” in this world. Make the most of every opportunity. Carpe deum. You only live once! This is the message we often hear at commencement speeches in schools across the Western world.

This is a good desire. We need to praise people who make a difference. In Genesis 2, God puts Adam and Eve in the garden to work the garden, to cultivate order, beauty, and goodness. God’s mandate to humans is to seize opportunities to leave this earth better than how we found it. This is a God-given desire and mandate.

But we fall short. Although we are good people, we still fall short of the ultimate good of worshiping God. Just like my car is good as transportation, but not good enough to be my friend, we are good in our deeds, but not good enough to be God’s children. We fall short of this ultimate good. We are not the best we can be. And if we were true to ourselves, we would know that although we are good people, we’re not good enough. But Jesus can help us to be the best we can be. We see this in the parable of the Pharisee and the tax collector. The Pharisee is a good person. It is good that he is generous with his money. It is good that he is faithful to his wife and does not cheat on her. He needs to be praised for this. He’s making a difference! But the Pharisee fails to see that he is not good enough to be a child of God; this is the point of the following passage with the children coming to Jesus as children (Luke 18:15–17) and not as a rich, lawkeeping ruler (Luke 18:18–30). We need to humble ourselves—admit that we fall short (as the tax collector does)—and ask Jesus to “exalt us” (Luke 18:14), making us the best we can be: children of God.

Using Peace as a Metaphor for Salvation

The Bible gives us many metaphors for our salvation blessings—union, adoption, justification, sanctification, redemption, reconciliation, freedom, regeneration. But Graham Cole believes that the umbrella metaphor for all of these salvation metaphors is peace or shalom.11

This is the ultimate existential cry of every human heart. Peace. Because of the curses in Genesis 3, we are not at peace with our work, our identity, our roles, the environment, our bodies, our friends, our family, and ultimately God. Today’s society has so many fractured relationships at home and work that we are longing for peace. Every aspect of our lives is affected by disharmony, disruption, and despair. Peace is the opposite of our lives. This means if we allow our friends to talk about their work, health, family, and relationships, we will soon hear them talking about their search for peace.

Every child longs for peace. The sound a child hates the most is the sound of their parents fighting. They would do anything for that sound to stop. Or consider my friend and his wife. They lived in an apartment and could always hear the couple next door fighting. One day, my friend was able to talk to the man next door. He looked stressed and exhausted. So my friend asked the man what was wrong. The man said to him, “I need peace. I’m looking for peace. I need peace.” So my friend was able to use peace to begin a conversation about Jesus with the man next door.

Do I Need to Use the Word Sin?

You might wonder whether the word sin is still the best word to use when talking with people today. Why not? Why shouldn’t we use the word sin to communicate the idea of sin? I’ll say two things. First, Jesus himself often doesn’t use the word sin to describe sin. Instead he uses metaphors, picture language, and stories to communicate the idea of sin. For example, in the parable of the rich fool, sin is painted as “storing up riches for yourself” and “not being rich toward God” (Luke 12:21). In the parable of the lost sheep, sin is painted as finding oneself lost, not as an act of willful rebellion, but that’s just what happens to sheep (Luke 15:1–7)! In the parable of the Pharisee and the tax collector, sin is painted as being confident of one’s righteousness and looking down on others (Luke 18:9). Jesus doesn’t use the word sin, and yet the idea is vividly communicated. This is the basic premise of theology—that a biblical idea can be communicated without using the word for that idea (for example, the Trinity).

Second, I believe it might be more helpful not to use the word sin in our culture. Francis Spufford, in his book Unapologetic, explains that the meaning of the word sin in the English language has changed in recent decades. Its meaning is now closer to the idea of a guilty, playful pleasure, like chocolates, ice cream, or lingerie. Something that we have a delightful giggle about.12 As with other words in English whose meanings have changed over time—thong, gay, dumb—we can’t expect our listeners to hear the intended meaning when we use it. We might have to use different words to communicate the same meaning.

There Are Many Ways to Share the Gospel

The gospel is God’s story about how he saves the world through Jesus. For those who respond with faith and obedience, there will be salvation: entry into the kingdom! But for those who don’t respond this way, there will be judgment and condemnation.

But the Bible itself uses a wide range of metaphors, genres, and styles to present this gospel. Jesus and his apostles used a variety of presentations for their different audiences. We are also free to explore a variety of gospel presentations. We can use different gospel metaphors—freedom, adoption, peace, honor—looking for the one that will best connect with our audience existentially, emotionally, and culturally.

THREE COMMON GOSPEL PRESENTATIONS

As a learning exercise, we can look at three common and recent gospel presentations. From these we can see that there is no one-size-fits-all gospel presentation. As summaries of the gospel, they all have strengths and corresponding weaknesses. And as our analysis will show, this indicates that we need to use a variety of gospel presentations.

1. Two Ways to Live: Matthias Media

The Two Ways to Live gospel presentation was developed in the 1980s for college ministry in Sydney, Australia. It was highly welcomed by many Christians—especially me!—because it helped explain the gospel clearly, easily, and succinctly. The pictures were easy to learn and draw. The Bible verses were easy to recite. The step-by-step presentation was engaging and easy to present to non-Christian friends. And it was hard hitting; it didn’t back away from hard truths such as condemnation, hell, judgment, and penal substitution.

It is an example of brilliant contextualization for its time. Most students on college campuses in the 1980s would have gone to Sunday school or had some sort of religious education. But in college, they experimented with their newfound freedom away from home. At some stage, they hit an existential crisis—“What am I doing here?”—similar to that of the prodigal son (Luke 15:17). If someone presented them Two Ways to Live, they would readily identify as the rebel who needed to come back and submit to God’s rule.

But as with all contextualization, what speaks well to one audience won’t speak so well to another. With the cultural shift into postmodernity, some features of Two Ways to Live no longer resonate. The chief metaphors—God as King, sin as rebellion, and salvation as submission—find little existential traction in the postmodern West, where authority figures impose their artificially constructed laws upon us to take away our freedom and authenticity. That’s why in the postmodern West our moral heroes are the rebels who resist and overthrow authorities such as kings to preserve freedom and authenticity. Think of the American Revolution. Or the Australian bushranger. Or Braveheart and his cry of “Freedom!”

But again, please note we are applying these comments as a learning exercise. In defense of Two Ways to Live, it was never designed as a standalone evangelistic tract. Instead, its purpose was to be a summary for Christians to use as a framework for gospel conversations with their friends. To do it justice, you should read the full text of the Two Ways to Live presentation online instead of relying only on my brief summary: www.twowaystolive.com.

Here’s a summary with a few images from the presentation:

| 1. |  |

God is the loving ruler of the world. He made the world. He made us rulers of the world under him. But is that the way it is now? |

Revelation 4:11 |

| 2. |  |

We all reject the ruler—God—by trying to run life our own way without him. But we fail to rule ourselves or society or the world. What will God do about such rebellion? |

Romans 3:10–12 |

| 3. |  |

God won’t let us rebel forever. God’s punishment for rebellion is death and judgment. God’s judgment sounds harsh but . . . |

Hebrews 9:27 |

| 4. |  |

Because of his love, God sent his Son into the world: the man Jesus Christ. Jesus always lived under God’s rule. Yet by dying in our place, he took our punishment and brought forgiveness. But that’s not all . . . |

1 Peter 3:18 |

| 5. |  |

God raised Jesus to life again as the ruler of the world. Jesus has conquered death, now gives new life, and will return to judge. Well, where does that leave us now? |

1 Peter 1:3 |

| 6. |  |

The two ways to live: A. Our way - reject the ruler, God - try to run life our own way Result: - condemned by God - facing death and judgment B. God’s new way - submit to Jesus as our ruler - rely on Jesus’ death and resurrection Result: - forgiven by God - given eternal life |

John 3:36 |

Two Ways to Live © Matthias Media, Sydney. Used by permission. To read the full Two Ways to Live tract text, visit twowaystolive.com.

Analysis of Two Ways to Live

The chief gospel metaphors are:

- God is King.

- Sin is rebellion against this King.

- The judgment for sin is punishment from God.

- Salvation blessings are forgiveness and eternal life.

- Jesus is the King who died in our place.

- The Christian life is submission to God’s rule.

The strengths of this presentation are that it communicates:

- God’s sovereignty and right to be our ruler.

- The objective (vertical) aspects of our sin, judgment, atonement, and salvation.

- That we have sinned against God, are under God’s wrath, need to be justified by God, and need Jesus as our penal substitutionary sacrifice.

But the corresponding weaknesses are:

- It is weak on the warm relational aspects of the Christian life. God is not Father but King. Jesus is not our Shepherd, brother, or friend. He is the King we submit to.

- There is no joy in the Christian life, only submission.

- The world disappears in the last frame. It offers a platonized or spiritualized view of the material world. As a result, it struggles to explain how a Christian lives in this material world after submitting to Jesus. What do I actually do with this world now that I’m forgiven?

- It struggles to explain the worth of ethics, aesthetics, arts, culture, study, work, and wealth in the Christian life. As a result, it might place a priority on “sacred” work, such as so-called full-time ministry, over “secular” work.

- The Christian in the final frame is an individual. It struggles to explain the corporate aspect of Christian living.

- It can lead, in practice, to a deistic God who acts mainly in salvation-historical moments (creation, fall, redemption, consummation), but little in between. Although it is strong on salvation-history categories, it is weak on providence. It struggles to explain guidance, prayer, healings, and miracles.

2. Four Spiritual Laws: CRU (Formerly Campus Crusade for Christ)

This gospel presentation was developed in the 1960s for college campuses in the United States by Campus Crusade for Christ (now known as CRU). It too is an example of brilliant contextualization for its time. In the 1960s, the USA was in a time of social turmoil with the civil rights movement, the Vietnam War, the feminist movement, free love, oral contraception (the pill), the hippie movement, and student protests. A college student living away from home for the first time would have been lost. Where am I going? Where is this world going? What am I doing here?

So if someone said to them, “God has a loving plan for your life,” that is exactly what they wanted—and needed—to hear. But there are features of the Four Spiritual Laws that don’t resonate well anymore. The opening premise—that there are laws—is no longer accepted by a postmodern audience, because laws are social constructs imposed by oppressive authority figures.13

You can check out the Four Spiritual Laws gospel presentation at http://crustore.org/fourlawseng.htm. It’s also included in the appendix Here’s a summary:

Law 1: God loves you and offers a wonderful plan for your life.

Law 2: Man is sinful and separated from God. Therefore, he cannot know and experience God’s love and plan for his life.

Law 3: Jesus Christ is God’s only provision for man’s sin. Through him you can know and experience God’s love and plan for your life.

Law 4: We must individually receive Jesus Christ as Savior and Lord; then we can know and experience God’s love and plan for our lives.14

Analysis of the Four Spiritual Laws

The chief gospel metaphors are:

- God is Lover.

- Sin is a state of being; we are sinful.

- The judgment for sin is separation from God.

- Salvation blessings are to “know and experience God’s love and plan for our lives.”

- Jesus is the provision for our sin, and the means for knowing and experiencing God.

- The Christian life is to “know and experience God’s love and plan for our lives.”

The strengths of this presentation are that it communicates:

- God is warm, personal, loving, relational.

- It explains sin more as a state of being—who we are—rather than what we do.

- Judgment is a privation of good; we miss out on God’s love and plan.

- The Christian life is one of purpose and fulfillment.

- The category of providence is prominent.

But the corresponding weaknesses are:

- It almost makes me the most important person in the universe!

- The Christian life is individualized; it struggles to explain the corporate nature of the Christian life.

- What if we already have fulfillment through other things—sports, work, partying? Why do I need God if I’m already happy?

- The category of salvation history is not so prominent.

Comparing Two Ways to Live and Four Spiritual Laws

While Two Ways to Live predominantly utilizes the categories of salvation history (creation, fall, redemption, consummation), Four Spiritual Laws predominantly relies on categories of providence (God’s ongoing interaction with us and his creation). This has led to some interesting developments.

Most of my American Christian friends have grown up familiar with the Four Spiritual Laws. I’ve also noticed that, in general, they are more articulate with the language of providence. For example, if you ask an American missionary why she decided to leave her successful career in medicine to become a missionary, she might say, “Because God told me to.”

Americans who grew up with the Four Spiritual Laws also tend to be more concerned with God’s guidance: What is God’s loving plan for my life? Where does God want me to live? Who does God want me to marry? They need to find God’s plan and remain in it! The strength of this is a healthy concern with prayer and guidance. There is also a healthy concern with how to be part of God’s plan to make a difference in this material and secular world. A weakness might be that they are led more by their subjective emotions and experiences than other objective factors. Another weakness is that it makes it hard to deal with failure, sickness, and suffering. How can this be part of God’s loving plan for my life?

Conversely, many of my Australian Christian friends have grown up more familiar with Two Ways to Live. They are less articulate with the language of providence. For example, if you ask an Australian youth pastor why he decided to leave his successful job in medicine to go into full-time paid ministry, he might say, “Because my pastor encouraged me to.” And if he said, “Because God told me to,” his answer might be viewed with suspicion.

Similarly, my Australian Christian friends often have little to say on seeking God’s guidance. If I ask them, “Should I be an engineer or a lawyer?” they might answer, “It doesn’t matter as long as they are moral jobs (unlike being a bank robber).” Or if I ask, “Should I marry Jane or Jill?” they might answer, “Doesn’t matter as long as she’s a Christian and not already married.” They tend to think in salvation-historical, sacred, and spiritual categories rather than providence, secular, and physical categories. If I ask them, “Should I be an engineer or a lawyer?” they might even answer, “It doesn’t matter as long as you give up that job and go into full-time paid ministry!” This leads to a limited Christian ethic where the application for almost any sermon or Bible study is “Tell your friends about Jesus” or “Give your money to missions” or “You should go into full-time paid ministry.”

3. The Bridge to Life: Navigators

The Bridge to Life, produced by the Navigators, is a third gospel presentation. The Navigators were founded in the 1930s and ministered to sailors in the US Navy, but by the 1950s its ministry had spread to college campuses and beyond. The Bridge to Life is also an example of brilliant contextualization for its time. This was a time of traditions and modern beliefs when most Americans believed in right and wrong, good and bad. Further, the majority of Americans described themselves as religious, and many attended churches and Sunday schools. The nagging existential cry for many Americans was that they needed to live up to the expectations of family, duty, and religion; they needed to be good people.

So if someone said to them, “You need to be good,” that was common ground. They would readily agree. And then if you could show them that Jesus could help them meet the absolute standards of a holy God, that was something they wanted—and needed—to hear. But as with all contextualization, what speaks well to one audience might not speak so well to another. A twenty-first-century postmodern audience might believe that the absolute standards of good and bad do not exist. Worse, they are artificial constructs imposed upon them by those in power. They don’t share the assumptions of a previous generation.

You can check out the Bridge to Life gospel presentation at https://www.navigators.org/resource/the-bridge-to-life/.

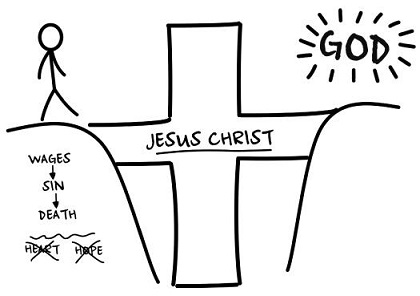

Here’s a summary including some visuals from the presentation to give you a sense of what it’s like:15

First, we have to start at the beginning. In Genesis 1:26, when God created the first humans, he said, “Let us make mankind in our image, in our likeness.” Then God blessed them and spent the days walking and talking with the people he had created. In short, life was good.

But why isn’t life like that anymore? What happened to mess everything up? This brings us to the second point: when we (humankind) chose to do the opposite of what God told us, sin poisoned the world. Sin separated us from God, and everything changed. Romans 3:23 says, “For all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God,” and in Isaiah 59:2 we’re told, “Your iniquities have separated you from your God; your sins have hidden his face from you so that he will not hear.”

This is especially bad news because there is no way for us to get across that gap on our own. We (humankind) have tried to find our way back to God and a perfect world on our own ever since then, and without any luck. We try to get there by being good people, or through religion, money, morality, philosophy, education, or any number of other ways, but eventually we find out that none of it works. “There is a way that seems right to a man, but in the end it leads to death” (Proverbs 14:12).

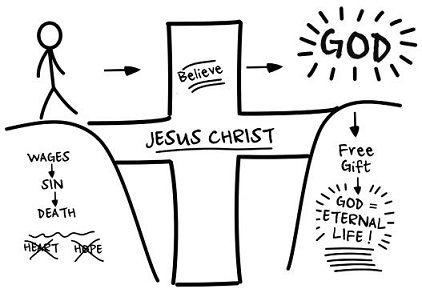

There is only one way to find peace with God, and the Bible says it is through Jesus Christ. We were stranded without any way of getting back to our Creator, and we needed a way to pay for our sins and be clean again so that we could be welcomed back to be with him. Romans 5:8 says, “But God demonstrates his own love for us in this: While we were still sinners, Christ died for us.” So this is the Good News—that even though we were still enemies of God (as one translation says), Jesus came to die on the cross and pay the price for our sins so that we could have a relationship with him again. John 3:16 says, “For God so loved the world that he gave his one and only son, that whoever believes in him shall not perish but have eternal life.”

What then should be our reaction to this awesome news? This brings us to the last and most important part. John 5:24 says, “I tell you the truth, whoever hears my word and believes him who sent me has eternal life and will not be condemned; he has crossed over from death to life.” Jesus Christ himself even says, “I have come that they may have life, and have it to the full” (John 10:10), and Romans 5:1 says, “we have peace with God through our Lord Jesus Christ.”

So how can I have peace with God, life to the full, and be confident of eternal life like these verses say? First, through an honest prayer to God, I have to admit that I’m not perfect—that I can’t escape my sins, and I can’t save myself. I follow this admission by believing that Jesus Christ died for me on the cross and rose from the grave, conquering death and sin. Then I invite Jesus Christ to live in me and be the Lord of my life, accepting his free gift of eternal life with him.

Analysis of Bridge to Life

The chief gospel metaphors are:

- God is Creator.

- Sin is doing the opposite of what God tells us.

- The judgment for sin is separation from God.

- Salvation blessings are peace, forgiveness, abundant life.

- Jesus pays the price for our sins.

- The Christian life is peace with God, life to the full, eternal life.

The strengths of this presentation are that it communicates:

- God is the Creator.

- Judgment is separation from God.

- The Christian life is a state of being—peace with God—rather than what we do.

But the corresponding weaknesses are:

- The Christian life is individualized; it struggles to explain the corporate nature of the Christian life.

- It has little to say about the material world and what we do once we are saved. It is similar to Two Ways to Live: the Christian life is mainly spiritual without much to say about the physical or material.

- Similar to Two Ways to Live, it might struggle to show the worth of ethics, aesthetics, arts, culture, study, work, and wealth in the Christian life.

Comparing Bridge to Life and Two Ways to Live

My PhD advisor, Graham Cole, pointed out to me that Bridge to Life and Two Ways to Live are good complements to each other. Two Ways to Live is well contextualized for college students who know they are living as rebels against God. It is well suited for prodigal son types such as Augustine or John Newton (who wrote the hymn “Amazing Grace”). They have wandered away from God and now must come back.

But Two Ways to Live is not well suited for zealous religious people who are trying to do the right thing by being good people. They are not transgressing or breaking God’s laws. They attend church regularly. They are upholding God’s laws piously.

Bridge to Life is much better contextualized for them. It shows that they are still separated from God, despite being good. In the end, they need to trust Jesus. Real-life examples of people who might respond to this approach include Saul (Paul before his conversion) in the Bible and Martin Luther before he discovered that justification comes by faith and not good works.

Gospel Summaries

We have surveyed three common gospel presentations. They are summaries of the gospel, designed to be brief and sharply focused on key gospel metaphors. They are designed with a specific audience in mind. They aim to connect at emotional, existential, and cultural levels. That is their strength.

But because they are summaries, each one must necessarily leave out some key biblical ideas. For example, if we emphasize salvation-historical categories, we might leave out providence. Or if we emphasize the need for an individual decision, we leave out the need for corporate responsibilities. Or if we emphasize the spiritual salvation blessings, we leave out the physical aspects of the Christian life.

What is well contextualized for one audience might not be well contextualized for another. If all we use is one gospel presentation, we won’t be able to engage a wide variety of audiences. Moreover, if we use only one gospel presentation, it will lead to reductionism in our theological understanding and practice of the Christian life.

Instead, we should develop familiarity with a wide variety of presentations. Jesus and the apostles changed their presentation and how they shared their message according to their audiences. This should free us up to do the same. It also means it’s unfair for us to criticize other gospel presentations that are different from ours simply because they focus on a different set of gospel metaphors from ours.

ANOTHER GOSPEL PRESENTATION: MANGER, CROSS, KING

In chapter 1, I mentioned the approach used by Timothy Keller as an example of how we utilize storytelling in sharing the gospel. In a talk titled “Dwelling in the Gospel,” Keller suggests using the following approach to giving a gospel presentation, which he says he gets from Simon Gathercole.16 We tell the story of how Jesus comes to us in three stages:

- Manger

- Cross

- King

First, Jesus comes to us in the manger. This is the theological idea of the incarnation. Jesus, the Son of God, comes to us as a servant. He healed the sick. He uplifted the oppressed and marginalized. He preached against established religion and authority. The significance is the reversal of values in the gospel: the first will be last, whoever loses their life will find it, whoever wants to be a leader needs to be a servant.

Second, Jesus dies for us on the cross. This is the theological idea of the atonement. Jesus has to die for us in our place. The significance is the necessity of penal substitution: we are sinners who can be saved only by God’s grace. Third, Jesus is the King who will set up his kingdom on earth. This is the theological idea of renewal and restoration. The significance is that we can have a renewed life. But not only that, this earth will be renewed. So we also have a corporate responsibility in renewing and restoring the physical world.

Like all summaries, this one has some deficiencies. For example, there is little on God as Creator. It assumes knowledge of God as the monotheistic Christian God who created the world in Genesis 1. But I like this gospel presentation for three reasons. First, it does a better job than most gospel presentations in juggling the tensions between salvation history and providence, individual salvation and corporate responsibility, and the spiritual and physical aspects of the Christian life. We are saved as individuals, but we have entered a corporate kingdom where we have a role in restoring the physical world by bringing Jesus’ love, mercy, justice, beauty, goodness, peace, and truth to those around us on this earth.17

Second, I can easily use the structure of manger, cross, King in a variety of contexts. For example, if I am conducting the Lord’s Supper and need to give a summary of the gospel, I can say, “The Lord’s Supper celebrates how Jesus came to us as a human, because he really did eat a physical meal with his disciples two thousand years ago. And that he died for us on a cross, because the meal symbolizes his body, which was broken, and his blood, which was shed for us. And it looks forward to that day when Jesus will set up his kingdom here on earth and we will eat at a banquet with him.”

Third, it presents Jesus as a person in a story. He comes across as real. He is someone we are to know, love, and worship. He didn’t just die on a cross for us. He also had a vital earthly ministry.18 In contrast, I think, our traditional gospel presentations (Two Ways to Live, Four Spiritual Laws, Bridge to Life) risk presenting Jesus as a propositional fact to acknowledge.

CONCLUSION: USING A DIVERSITY OF GOSPEL METAPHORS

We began with the story of Jim. The gospel was presented to him using biblical metaphors of guilt and forgiveness. It connected with him existentially, emotionally, and culturally. But those same biblical metaphors had less connection with his daughter, Megan. Worse, they served only to reinforce her culture’s hostility to organized religion and institutionalized authority.

In this chapter, we have surveyed a variety of gospel metaphors. Hopefully this will free us up to use additional metaphors for God, Jesus, sin, condemnation, salvation, and the Christian life. For example, in addition to explaining sin as breaking God’s law, we can explain to Megan that sin is dishonoring God, feeling morally superior to those around us, brokenness, or being owned by whatever we’re living for. And we can explain salvation blessings to Megan as freedom, adoption, peace, or honor.

In this chapter, we also surveyed a variety of gospel presentations. We found that there are many good biblical ways to share the gospel. But that doesn’t mean they are the only ways. Nor should we insist upon them. This should also empower us to explore a wide range of gospel presentations for our specific audiences. For example, if we presented the gospel to Megan, we might choose a gospel presentation that emphasizes the need to be at peace with God, and the part that she can play in the renewal and restoration of this world, especially by bringing Jesus’ love, mercy, justice, and beauty to this earth.

Hopefully this chapter will get us excited about the large repertoire of metaphors that God has provided for us in the Bible. For each and every one of our non-Christian friends, there should be a metaphor that we can use to connect the gospel with them at emotional, existential, and cultural points of entry.

1. Henri A. G. Blocher, “Sin,” in New Dictionary of Biblical Theology (Leicester, UK: Inter-Varsity, 2000), 782.

2. My synthesis of Paul G. Hiebert, Transforming Worldviews: An Anthropological Understanding of How People Change (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker, 2008), 62.

3. Jackson Wu gives us a detailed treatment on the subject of shame, honor, and face in Jackson Wu, Saving God’s Face: A Chinese Contextualization of Salvation through Honor and Shame, EMS Dissertation Series (Pasadena, Calif.: William Carey International Univ. Press, 2012).

4. Jon Ronson, So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed (New York: Riverhead, 2016).

5. David Brooks, “The Shame Culture,” New York Times, March 15, 2016, http://www.nytimes.com/2016/03/15/opinion/the-shame-culture.html. Accessed January 3, 2017.

6. See also Andy Crouch, “The Return of Shame,” Christianity Today, http://www.christianitytoday.com/ct/2015/march/andy-crouch-gospel-in-age-of-public-shame.html. Accessed January 3, 2017.

7. I refer you to an excellent article by Claire Smith, “Broken Bad,” GoThereFor.com, May 13, 2016, http://gotherefor.com/offer.php?intid=29295. Accessed July 31, 2016.

8. Stephen Biddulph, The New Manhood: The Handbook for a New Kind of Man (Sydney: Finch, 2010), 20.

9. For example, Timothy Keller, Center Church: Doing Gospel-Centered Ministry in Your City (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Zondervan, 2012), 126–28.

10. I owe these insights to Todd Bates and Adam Co.

11. This is Graham Cole’s chief argument in God the Peacemaker: How Atonement Brings Shalom (Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity, 2009).

12. Francis Spufford, Unapologetic: Why, Despite Everything, Christianity Can Still Make Surprising Emotional Sense (San Francisco: HarperOne, 2013), 24–27.

13. I owe this observation to my PhD supervisor, Graham Cole.

14. Have You Heard of the Four Spiritual Laws? written by Bill Bright © 1965–2017 The Bright Media Foundation and Campus Crusade for Christ, Inc. All rights reserved. http://crustore.org/four-spiritual-laws-online/. Included with permission.

15. Adapted from www.navigators.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/navtool-bridge.pdf. Bridge to Life © 1969, The Navigators. Used by permission of The Navigators. All rights reserved.

16. Tim Keller, “Dwelling in the Gospel,” delivered at the 2008 New York City Dwell Conference, April 30, 2008.

17. For a fuller development of this idea, see N. T. Wright, Surprised by Hope: Rethinking Heaven, the Resurrection, and the Mission of the Church (San Francisco: HarperOne, 2008).