CHAPTER 5

CONTEXTUALIZATION FOR EVANGELISM

If Jesus came today, would he be a white man?

Adam is excited to be a youth pastor at a small church in Southern California. After growing up on a farm and studying in midwestern America, this is his first time on the West Coast. He is looking forward to the sunshine, walks along Venice Beach, and watching the sun set over the Pacific Ocean.

At the youth group meeting, Adam meets a fifteen-year-old girl named Jane. Her parents are from Taiwan, but Jane grew up in America. Her father stays in Taiwan to work, while her mother lives with Jane and plays the role of the “Asian Tiger Mom.” Jane studies for hours and hours every day. She doesn’t play any sports or go to summer camps. Instead, she attends tutoring for her math. Jane’s ambition is to go to Harvard. And one day she will become a doctor.

As her youth pastor, Adam notices Jane’s obsession with her studies and confronts Jane. He warns her that study has become her idol and tells her that she needs to repent from this. He tells her that she needs to realize that there is more to life than Harvard, and that being a doctor may be a worse thing to do because it will make her rich and worldly. If she’s really serious about following Jesus, she should give up her dreams of being a doctor and be a missionary instead. Or better yet, she should consider becoming a youth pastor!

“DO I HAVE AN ACCENT?”

When I was living in the USA, Americans would often say to me, “Oh, I love your Australian accent!” They would always follow this up with, “Do I have an accent to you?” Which was staggering to me. Because of course they had an accent—an American accent! But even more staggering was the fact that they didn’t realize they had an accent, as if they of all people in the world were the ones without an accent. The whole world has an accent—except for them!

I would also meet Americans who would try to convince me that they had a neutral accent. A midwestern American once told me that the midwestern accent was the neutral accent. That’s why they try to find newsreaders with a midwestern accent, rather than a southern or East Coast accent. Another time, a Californian told me that the Californian accent was the neutral accent. That’s why movies were made in California, because the Californian accent was neutral to the whole world!

Now, this was truly staggering. Because not only were they saying they had a neutral accent; they were implying that their accent was the normative accent. Their way of speaking English was the universal accent for the whole world.

Many Christians are the same with regard to their culture. They do not realize they have a culture, so they cannot hear their cultural accent. They cannot taste their cultural flavoring. They aren’t aware of their dress or the Christian songs they sing or their views on education, work, and smoking. And so they impose their culture, along with the gospel, as if it is normative and universal.

At the youth group meeting, Adam also meets a fifteen-year-old boy named Jack, a thorough Californian dude. Jack wears his board shorts all year round. He doesn’t enjoy high school. Once the end-of-school bell rings, Jack jumps on his bicycle and rides to the beach to go surfing. Jack’s ambition is to leave school when he turns sixteen and take up a day-labor job so he can surf every day with his buddies.

As his youth pastor, Adam confronts Jack. He warns him that surfing has become his idol. He needs to repent from this. And Jack needs to realize there is more to life than the beach. He tells Jack that dropping out of high school is a terrible thing to do because Jack will be wasting his God-given potential to study. If Jack is really serious about following Jesus, he should stop surfing and apply himself at school. That way he can get into a college and one day get a decent-paying job. Or better yet, he can become a youth pastor!

Did Adam give these students the gospel, or did he give them his own culture? Can you see what’s happened here? Adam has asked Jane to be like Jack, and Jack to be like Jane. Even worse, Adam’s asking them to be like himself.

Many Christians are like Adam. They have merged their own culture with the gospel. This is what missionaries call syncretism. In doing so, when they evangelize, they don’t just give the gospel. They also impose their culture upon the convert. By doing this, Christians are asking people not only to convert to Jesus but also to convert out of their culture into another culture, usually the culture of the Christian evangelizing them. Just like Western missionaries long ago forced Africans and Asians to wear Western clothes, Christians today force converts to leave their old culture and join Christian culture. So the question we want to address is, How can Jane be a Christian and still be an Asian-American? How can Jack be a Christian and still be Californian surfer dude? This chapter will answer this question by exploring the topic of contextualization as we look at the relationship between gospel and culture.

WHY CAN’T I JUST GIVE THEM THE GOSPEL?

Have you ever had a well-meaning Christian say, “All you have to do is give them the gospel”? And by implication, they are saying, “Why do we have to worry about culture?” To answer this question, let’s consider a few scenarios.

Scenario 1: Seek to Be Understood

I’m going to tell you the gospel: Denn so hat Gott die Welt geliebt, daß er seinen eingeborenen Sohn gab, damit jeder, der an ihn glaubt, nicht verloren gehe, sondern ewiges Leben habe.

That is John 3:16, the gospel in a nutshell! The timeless, universally true gospel. But it is in German, which most of you reading this book likely don’t understand. So at the very least, we should admit that it’s not enough to tell the gospel in a way that makes sense to us; we also need to translate it so we can be understood.

Scenario 2: Be Sensitive

I’m going to tell you the gospel: “God so loved the world that he gave his one and only Son, that whoever believes in him shall not perish but have eternal life.”

That is the gospel. And you understood it in English. But what if I had said it to you with my fly undone, speedos on my head, and pointing my index finger at you? The problem here is that I have been culturally inappropriate. In your culture, I have been offensive. Because of my appearance and actions, I am not credible. So it’s not enough to tell the gospel; we need to be sensitive to the other person’s culture.

If we understand another person’s culture, then we have a better chance of being understood. We will also seek to be sensitive and not unnecessarily offend them. In education there is a saying: “To teach math to Johnny, you need to know both math and Johnny.” In evangelism, we can similarly say, “To tell the gospel to Johnny, we need to know both the gospel and Johnny.” We need to know both the gospel and Johnny’s culture.

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE GOSPEL AND CULTURE

The Gospel Is Transcultural

The gospel is transcultural because it is true for all cultures. In the Old Testament, God is the God of both Israel and the nations. In the New Testament, salvation is for both the Jews and the gentiles. This is why Paul can say that in Christ there is neither Jew nor gentile, slave nor free, male nor female (Gal. 3:28). For this reason, we will all answer before the same God on judgment day. The gospel is universal and normative for all peoples at all times and in all places.

The Gospel Is Enculturated

But the gospel is not acultural, as if it hovers above culture and is devoid of any culture. Instead, the gospel is deeply enculturated.1 Notice how enculturated these biblical terms are:

The God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob

The Jewish Passover

Priests, temple, sacrifices

Jesus the Lamb of God

Jesus the Shepherd

Ransom for many

Taking up your cross

Washing each other’s feet

Pharisees, tax collectors, Sadducees, Samaritans, fishermen

That is why we have to explain the Bible’s culture whenever we give a story or talk from the Bible. Whenever we teach the Bible to children or newcomers, we often begin with the phrase, “In their culture . . .”

Even the Son of God became enculturated. When John says “the Word became flesh and dwelt among us,” he is saying that the second person of the Trinity became a first-century Jewish male who lived in Roman-occupied, Second Temple Palestine and grew up in a working-class family. To understand the gospel, we need to understand its culture. We need to do cultural hermeneutics.

Our Audience Is Enculturated

The person we are trying to evangelize is also enculturated. They are not a person who hovers above culture and is devoid of any cultural influences. Instead, this person is deeply enculturated. And this can vary widely, even within the same geographical area. For example, if the person lived in Chicago, they could be from an:

American-born Chinese culture

African-American culture

Northwestern undergrad culture

Kellogg Business School culture

Community college culture

North Beach culture

Single mom culture

Retiree culture

Each one of these is a unique and distinct culture in the Chicagoland area. Each would have different cultural concerns, gospel interpretation, cultural communication, and cultural application.

Cultural Concerns

For example, the American-born Chinese is concerned about honoring the family and pressures to study. The retiree is concerned about loneliness, health, and boredom. The single mom is concerned about time pressure.

Gospel Interpretation

The gospel will be interpreted and misinterpreted differently by each culture.2 What does their cultural lens help them to see in the Bible? What are their cultural blind spots which make them misunderstand what’s in the Bible?

For example, an American-born Chinese might come to the Bible with the lenses of the Confucian worldview. They may correctly understand that they have shamed God and now need to honor this God, but they might misunderstand the requirements to obey this God as duty, perfectionism, and salvation by works.

As another example, a Californian surfer dude might come to the Bible with the lenses of Western individualism. He may correctly understand that he needs to make a personal decision to follow Jesus, but he might be culturally blind to his corporate responsibilities in the body of Christ.

Cultural Communication

For people to understand you, you must speak in ways that their culture can understand. We often take this for granted. An Anglican bishop once told a missionary friend of mine that he didn’t believe we needed any form of contextualization. My missionary friend replied, “At least you’re using English rather than Greek.”

This is especially important because much of our language is idiomatic. This means that we have to learn not only a culture’s language but also its idioms, metaphors, and illustrations. A friend of mine, Leigh, was having lunch at a popular tourist destination in Sydney. Leigh was approached by a Chinese tourist. The tourist asked Leigh if he could use the vacant seat next to him. Leigh replied, “Go for your life!” When the tourist heard this, he ran away. Of course, what Leigh had meant was, “Sure, the seat’s free, take it!” but the tourist thought Leigh was threatening him! This story shows how much of our communication is idiomatic. “Take a seat,” “I want to ride shotgun,” and “What’s up?” are just some common examples.

I’ve also heard it said that people from foreign countries—China, Belgium, Brazil—who learn English as a second language still have trouble understanding native speakers from the USA, England, and Australia speaking English. But—and here is the interesting part—those from foreign countries can easily understand each other speaking English. This is because they have learned a technically precise English, but one which is different from the idiomatic English spoken by native speakers.

In addition to idioms, the way we organize and present our ideas is also culturally determined. Some cultures prefer a propositional, point-by-point presentation. Other cultures prefer stories, illustrations, and examples. All of this affects the way we communicate.

Cultural Application

The gospel will also be applied differently in each culture. What are the idols of a culture? How can they honor God in their context? What does it mean to take up your cross in that culture? For example, when an American-born Chinese becomes a Christian, they face a challenge: “How can I honor God without dishonoring my non-Christian parents?”3 The surfer dude might face a different challenge: “How can I honor God without letting down my friends?”

My PhD supervisor, Graham Cole, pointed out to me that in Luke 3:10–14, John the Baptist had different applications of the gospel for different audiences. To the crowd, John told them to share food and clothing. To the tax collectors, John told them to stop cheating. To the soldiers, John told them to stop extorting money and to stop accusing people falsely. If you’ve ever taught in another cultural context, you’ve likely faced the struggle of trying to give application to your ideas in that culture. The struggle you faced in doing this reveals that you are already implicitly doing some form of cultural hermeneutics.

The Gospel Teller Is Enculturated

We ourselves as evangelists are also enculturated. We are not free-floating people hovering above the culture, devoid of any culture. We are not acultural. We each have a cultural accent and a cultural flavor. We are deeply enculturated, and this will affect our understanding and application of the gospel.

Our Own Cultural Concerns

We come to the Bible with our own cultural, theological, existential, emotional, and experiential concerns—consciously or unconsciously. For example, when I was feeling lonely, I came to the Bible looking for God’s comfort. Or when I was wronged, I came to the Bible looking for God’s justice.

But what we’re talking about is more than just our felt needs or feelings. In my theological tradition, I’ve been used to the idea that Jesus died for me. So I’ve quickly noticed Bible passages with the “for us” language—that Christ died for us (e.g., Rom. 5:8). Now, as I read and listen, I hear more theologians pointing out that Christ isn’t just for us; we are also in him (our union with Christ). So now I’m noticing Bible passages with the “in him” language as well (e.g., 2 Cor. 5:21). But how did I miss such obvious language before now? Because it wasn’t part of my theological concerns until now.

Our Own Interpretation of the Gospel

We are not blank slates. We bring our own theological interpretive grids to the Bible. For example, in John 4, when Jesus tells the Samaritan woman she has had five husbands, and the man she is with isn’t even her husband, what do we think of the woman? We automatically think she’s an adulteress. She’s a sinner.

But in other cultures, they might interpret the story to mean that she has been abandoned unfairly by five men, one after the other. And she now lives with another man for protection. But this man won’t even honor her by marrying her. She’s been sinned against.

There’s nothing in the text to tell us whether she’s a sinner or sinned against. But we come to our interpretations based on the theological systems that we have brought to the text.4

Our Own Cultural Communication

I have lived in both the USA and Australia. An Australian friend once joked to me, “Never have two countries been divided so much by a common language!” That’s because even though Americans and Australians both speak English, our words can mean different things. For example, in the USA, college refers to an undergraduate institution and school refers to a postgraduate institution. But in Australia, it’s the other way around! As another example, in the USA, if you take a class, then you are the student in the class. But in Australia, if you take a class, then you are the teacher of that class. As a final example, in the USA, you order “take out.” But in Australia, you order “take away.”

It’s the same for us when we communicate the gospel. Words that mean one thing to our particular Christian tradition might have a completely different meaning to a non-Christian in their culture. Take the word evangelical. In our Christian tradition, it might mean a characteristic of a denomination or movement within Christianity that holds to the primacy of the gospel message—from the word euangelion. But to our non-Christian friend, it may mean a sociopolitical movement associated with the conservative right.

And these differences can be even more profound. In our Christian tradition, we might associate a particular formulation of the gospel as the gospel itself—Two Ways to Live, the Four Spiritual Laws, or Bridge to Life. If so, we might wrongly think that unless we tell the gospel in this particular way—using its metaphors of sin and salvation—then the gospel has not been proclaimed. In some Christian traditions and denominations, we proudly announce that we preach “Christ crucified” (the gospel) and not rhetoric (citing 1 Cor. 1:18–2:16). But what we usually fail to realize is that we do employ a rhetorical method when we present the gospel. We can’t escape it. The rhetorical method is usually one that we are so used to in our culture, denomination, or tradition that we don’t notice it. For example, it could be the twenty-minute Bible talk with an introduction, three points, and a conclusion. Or it could be several key points presented in logical order. We are always using a rhetorical method—usually one determined by our culture—whether we acknowledge it or not.

Our Own Application of the Gospel

I come from a Sydney culture where the application for almost every New Testament passage was, “Give up medicine, go to seminary, go into professional ministry, and become a pastor.” When I travelled to Siberia, their preachers applied every New Testament passage as, “You must not drink alcohol.” If you are an American, there is a better than average chance that your American pastor applies almost every New Testament passage as, “You must do daily devotions, pray more, and give more money to missions.”

These may or may not be valid applications. But it should be obvious that those who evangelize have interpretations and applications that are deeply influenced by their culture. If we become better exegetes of our own culture, we will become aware of our enculturated interpretations and applications of the gospel. In doing so, we will be aware of our reductionisms and our blind spots. And in our evangelism and presentation of the gospel, we will become more richly layered and nuanced in our communication.

There Is No Universal, Decontextualized Form of the Gospel

There is no form for presenting the gospel that hovers above a culture, devoid of culture. We have to pick a particular form that speaks to one culture, but may not be able to speak to another culture.

Timothy Keller helpfully explains that the instant you present the gospel, you have chosen to be contextual, historical, and particular.5 Jesus did this when he chose to be male, Palestinian, first century, and Aramaic and Greek speaking. And we do it when we choose our form of communication. For example, we have to choose a language. If we speak in English, only English-speaking people can understand us. And we still have these choices:

- What kind of English will we choose?

- Who do we quote?

- How do we illustrate?

- Do we use humor?

- What metaphors do we use?

- What clothes do we wear?

- What questions do we answer?

For example, an Asian-American audience might ask you what to do with their parents. A western African audience might ask you about lightning: Why does God send lightning which kills their children? An American audience might ask you what God’s perfect plan is for them. Keller reminds us that we shouldn’t be dogmatic about our preferred forms of evangelism. They might work well in our cultural setting, but they may not work well in other settings. Whatever it is that makes it work well in our setting might be the very thing that makes it not work elsewhere.

My missionary friend Bruce tells me that when he was in western Africa, well-meaning American missionaries were using the Four Spiritual Laws to tell the gospel to the Africans. Although it was effective on American college campuses, by and large they found it ineffective in traditional Africa. I come from Sydney, where my tradition uses Two Ways to Live as its evangelism tract. This tract worked very well in Sydney during the 1980s, and now we are trying to export it to the rest of the world. While it may work in some contexts, we should also pause to ask, “Could whatever it is that made it work well in the 1980s in Sydney mean that it may not work so well elsewhere in the world?” We can’t assume that what works in one place will be appropriate for a different cultural context.

If we want our gospel presentation to appeal to a wide variety of cultures, it will likely have to be quite generic—largely abstract. It might be more universal in its reach, but it will also be less engaging and effective. Conversely, if we want our gospel presentation to be highly contextualized to a specific culture, it will likely not engage people from another culture. For example, if we target Chinese who speak Chinese and work outdoors on weekend nighttime shifts, then we cannot possibly reach Germans who speak German and work indoors on weekday daytime shifts.

Every Form of Gospel Presentation Will Overadapt and Underadapt

According to author and pastor Timothy Keller, every form of gospel presentation will either overadapt or underadapt to a culture.6 This is true in both interpretation and application. For example, according to Romans 8:14–17, if we have God’s Spirit, then we are adopted as his children. We can cry out, “Abba, Father!” But how do we interpret this gospel truth—in particular, the Aramaic term Abba? If we read this to mean we can call God “Old Man,” we might risk overadapting our interpretation of the gospel to fit our cultural perspective—in particular, our egalitarian approach to hierarchical relationships. At this point, we are misinformed about the gospel. But if we leave Abba untranslated, then we risk underadapting our interpretation of the gospel for our culture. Now we are uninformed (or underinformed) about this aspect of a great gospel truth. We miss out on relating with God as Father.

As another example, if we use only brokenness and healing as our metaphors for sin and salvation, then we might risk overadapting our interpretation of the gospel to fit our cultural perspective—in particular, our loss of categories of guilt and retributive justice in the West. At this point, we are misinformed about the gospel. We might understand sin to be a sickness that can be healed by therapy, rather than as a vertical offence against a holy God, which requires our repentance and his forgiveness. But if we use only guilt and forgiveness as our metaphors, then we risk underadapting our interpretation of the gospel for our culture. Our culture is now uninformed (or underinformed) about other metaphors of sin and salvation, such as shame and honor, brokenness and healing, self-righteousness and exaltation, and falling short and restoration.

When we overadapt to a culture in application, we end up with syncretism to their culture. We don’t ask people in that culture to give up what they should give up according to the gospel. And we don’t ask them to do what they should do according to the gospel. The opposite is when we underadapt to a culture, where we end up with legalism from our culture. We think we’re imposing upon them gospel norms, but we’re actually imposing upon them our cultural norms. Here we ask them to give up what they shouldn’t have to give up. And we ask them to do what they shouldn’t have to do.

According to Keller, we are blinded by our culture. We cannot see our cultural blind spots. Because of this we will overadapt or underadapt our gospel presentation. Let’s use the example of the Bible’s view of sex. If we take the gospel to a culture and tell them that it’s okay to have sex with prostitutes to worship the local fertility goddess, then we are guilty of syncretism. We have overadapted our gospel presentation to their cultural norms. We haven’t asked them to give up things they should give up according to the gospel. But the opposite would happen if we tell them that they can have sex only in order to have children. We tell them it is wrong to have sex for any other reason, such as pleasure.7 Here we are guilty of legalism. We have underadapted our gospel presentation. We have asked them to give up things they didn’t have to give up. We have imposed upon them our cultural norms rather than the norms of the gospel.

The important thing to note here is that the opposite of overadaptation is legalism. Often we think there is a risk in overadapting (overcontextualization) to a culture because it would lead to syncretism. We think that it might be better to err on the safe side, to underadapt (undercontextualize). “Just stick to the gospel,” we say. But if we underadapt, we are giving them legalism instead of the gospel. The opposite of syncretism isn’t the pure gospel. The opposite of syncretism is legalism.

According to Keller, there will be no form of gospel presentation that can ever get it just right. We will always be overadapting or underadapting. But if we can get it just right, then we will hit the sweet spot of contextualization. And that is when revival, with God’s help, will happen!

ADAPTATION OF GOSPEL PRESENTATION TO CULTURE

| Underadapt | Sweet Spot | Overadapt | |

| The Evangelist and the Culture | You challenge but don’t enter the culture. | You enter and challenge the culture. | You enter but don’t challenge the culture. |

| Gospel Interpretation | They are uninformed (or underinformed) of gospel truths. | They are informed of gospel truths. | They are misinformed of gospel truths. |

| Gospel Communication | They can’t understand you. | They understand you. | They think they understand you, but they have misunderstood you. |

| Gospel Application | You make them do what they don’t have to do and ask them to give up what they don’t have to give up. | You make them do what they have to do and ask them to give up what they have to give up. | You don’t make them do what they have to do and don’t ask them to give up what they have to give up. |

| Gospel Presentation | Your gospel message has nonessentials that are confusing or unnecessarily offensive. | Your gospel message has essentials that are necessarily offensive but doesn’t have nonessentials so that you don’t confuse or unnecessarily offend. | Your gospel message doesn’t have the essentials so that it is inoffensive when it should have been necessarily offensive. |

| Result | Pharisaism, legalism, cultural imperialism (imposing cultural norms as gospel norms) | Contextualized gospel | Syncretism |

| Category of Contextualization (Hiebert)* | Colonialism | Critical contextualization | Uncritical contextualization |

* The final row of this table is from Paul G. Hiebert, “Critical Contextualization,” International Bulletin of Missionary Research 11 (1987): 104–12.

YOU DON’T HAVE “THE BIBLICAL WAY”

Timothy Keller gives a great example of adapting the gospel. All cultures find somewhere to sit on the individualism-versus-collectivism and hierarchy-versus-equality spectra. So who has got it right? Which is “the biblical way”?

North Americans are individualistic rather than collective in the way they think and live. As a result, someone might say that they are not biblical, and we should be less individualistic and more collective. Take, for example, the Amish. The Amish share their possessions, eat together, and work together. Surely this is more biblical than what we typically do in North America! But then someone might say, “What about the Auca Indians?” They are more collective than the Amish. They don’t live in buildings where you have privacy. You have to do everything in the open—going to the toilet, having a bath, and reading your mail.

So which is the biblical way—the typical North American, the Amish, or the Auca Indian way of living? Timothy Keller’s point is that there will always be someone who has overadapted more than you, and there will always be someone who has underadapted more than you. So be humble, because you don’t necessarily have it right. You don’t necessarily have “the biblical way.” Instead, be gracious to others. Don’t call them syncretists or legalists in their forms of evangelism. Because there will be someone else out there who can bring the same charge against you!

We have just looked at six aspects of the relationship between the gospel and culture. Hopefully you are beginning to see that saying, “Just give them the gospel,” is too simplistic (at best) and naive (at worst). If we are to present the gospel to someone, we need to be educated in cultural hermeneutics. We need to be able to exegete the Bible’s culture, the culture we are seeking to reach, and our own culture.

HOW TO INTERPRET CULTURE

So how, practically, do we study a culture? How do we learn to interpret culture? We need to learn the skills of cultural hermeneutics.

What Is Its System of Thought?

We can interpret a culture as it stands at a single moment by classifying it as a system of thought. How are its ideas organized into a comprehensive, interconnecting system? For example, James Sire in The Universe Next Door suggests the following systems: Christian theism, deism, naturalism, nihilism, existentialism, Eastern pantheistic monism, the New Age, and postmodernism.8 Simon Smart in A Spectator’s Guide to World Views suggests Christian worldview, modernism, postmodernism, utilitarianism, humanism, liberalism, feminism, relativism, New Age spirituality, and consumerism.9

These systems or worldviews can be a helpful place to start. But the weakness of classifications like this is that they consider Christian theism as its own entity, devoid of any other worldview, as if Christianity were its own culture. The lists also tend to be adversarial, presenting Christianity versus the other systems. This can be helpful in contrasting particular points of thought, but it can also be dangerously simplistic, because our theological doctrines of general revelation and common grace tell us that there must be some truth and goodness in these other systems of thought. There must be some overlap with the Christian worldview that we can identify within the other systems.10

What Are Its Themes?

We can also interpret a culture by looking at its themes. What are the dominant messages you hear in that culture? What is expressed? How does this culture answer the basic questions of life, meaning, and reality? Again, James Sire helpfully gives some guidance here. He suggests that the worldview of a particular culture can be discovered in the way it answers four key questions:

- Who am I? What is the nature, task, and purpose of being a human?

- Where am I? What is the nature of the universe and the world in which I live? Is the world personal, ordered, and controlled? Or is it chaotic, cruel, and random?

- What’s wrong? Why is it my world appears to be not the way it’s supposed to be? How do I make sense of evil?

- What is the solution? Where do I find hope for something better?11

Similarly, Simon Smart suggests that a worldview can be understood by what it says about the following six themes:

- Reality: What is the nature of the universe and the world around us? Is there a God or gods? Is this a closed or open universe? Is there only a material world or is there also a supernatural world?

- Human nature: What is a human being? Are we created or evolved? Is there only a body or also a mind or soul? Are we essentially good or evil? Is there free will or determinism? Are we nature or nurture?

- Death: What happens to people when they die?

- Knowing: How can we know? What can we know?

- Values: What makes something right or wrong?

- Purpose: What is the meaning of human history? What is the purpose of life?12

Kevin Vanhoozer offers yet another approach, one quite different from these approaches. He says that we can learn the themes of a culture by looking at how they view these ideas or categories: beauty, body, children, cities, gardens, gifts, guilt and shame, hope, justice, marriage, sickness, and worship.13

Following Vanhoozer’s lead, we can come up with our own list of themes by which to interpret a culture. For example, you might want to look into how the culture understands youth, age, work, sports, or leisure. Or you might study how they think about body hair, health, wedding presents, public transportation, and democracy. There is no single way to approach this, but some themes will likely be more helpful to you than others in communicating the gospel.

WHO DO YOU SAVE?

The themes of youth and age are often quite revealing. When I teach ethics, we often discuss this thought experiment. If a ship is sinking and you can put only one person onto the lifeboat, who will you choose—the eight-year-old girl or the eighty-year-old man? Interestingly, many of us in Western cultures would choose the eight-year-old because she has potential and the eighty-year-old has already lived his life. But many in traditional cultures would choose the eighty-year-old because society has invested so much in him.

What Are Its Themes and Counterthemes?

Paul Hiebert advocates looking at themes together with their opposites, what we can refer to as counterthemes. He suggests that every culture will belong somewhere on the following spectra between themes and counterthemes:14

| Individual |  |

Group |

| Private emotions |  |

Public emotions |

| Order, predictability |  |

Chaos |

| Material world |  |

Nonmaterial world |

| This-worldly |  |

Otherworldly |

| Secular space |  |

Sacred space |

| Achievement |  |

Acquirement |

| Hierarchy |  |

Equality |

| Freedom |  |

Control |

| Universal, whole picture |  |

Particular, specific |

For example, in traditional English and Australian cultures, emotions are private. If someone is authentic, then they shouldn’t show emotions. By showing emotions, they probably have something to hide. But in some Mediterranean cultures, emotions are public. If someone is authentic, then they should show emotion! When I worked as a doctor in Sydney, patients from an English culture would downplay their pain, whereas patients from Mediterranean cultures would demonstrate their pain with loud gestures and groans. But this worked against them because the healthcare staff assumed they were faking their pain. I remember one time a lady was having a heart attack, but no one believed her because she was groaning too loudly.

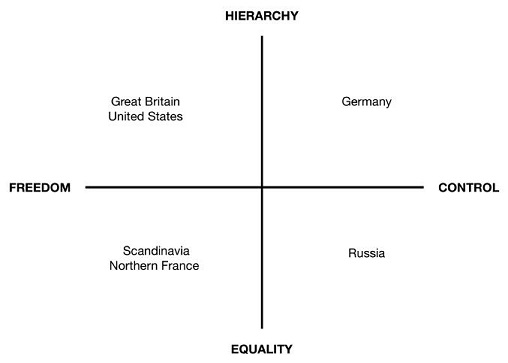

Hiebert suggests that at least two spectra, the themes/counterthemes of freedom-control and hierarchy-equality, can be combined to form a grid. (See figure.)

Paul G. Hiebert, Transforming Worldviews: An Anthropological Understanding of How People Change (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker, 2008), 27. Copyright 2008. Used by permission of Baker Academic, a division of Baker Publishing Group.

The grid should be self-explanatory. The cultures in Scandinavia, northern France, and Russia place a high value on equality. But Russia differs from the others in that it is a culture of control, while Scandinavia and northern France place a greater cultural emphasis on freedom. And the cultures of Great Britain, the USA, and Germany tend to have more hierarchy. But Germany is a culture that values control, while Great Britain and the USA tend to emphasize freedom to a greater extent.

When I taught this to my class in Sydney, I asked them where they would put Australia on the grid. We joked that Australia would be exactly in the center. We were neutral while the rest of the world was extreme in terms of equality, hierarchy, freedom, and control. But every culture thinks of itself as the neutral one. For example, China literally means “Middle Kingdom.” The British have Greenwich Mean Time, where Britain’s time is the reference point for the rest of the world. American maps of the world have America bang in the middle of the world map, even if this means Asia has to be divided into two on the edges of the map.

What Is Its Storyline?

The three methods I’ve outlined thus far give a synchronic reading of culture. But there is a fourth method that can give us a diachronic reading. Again, Timothy Keller helpfully shows us that each culture has its own storyline.15 Keller explains that stories typically have three parts:

- The way things should be: a mission, a task, a journey

- Something that stops this from happening: the bad guys

- Something that achieves the mission: the good guys

Keller uses the example of Little Red Riding Hood to illustrate this. “Little Red Riding Hood took food to her grandmother” is not a story. But “Little Red Riding Hood went to take food to her grandmother (the mission), but a wolf was waiting to eat Little Red Riding Hood (the bad guy), but a woodsman kills the wolf and saves Little Red Riding Hood and the grandmother (the good guy)” is a story. To interpret a culture, we need to ask, What is the storyline of this culture? What is its mission? What should the world be like? Where are they trying to go? Who should they be? Who are the good guys? Who are the bad guys? What is wrong with the world? What is stopping it from getting its happy ending? What is a sad ending and what is a happy ending for this culture?

Do you remember Jane and Jack from the introduction to this chapter? What are their storylines? What is their mission? Who are their bad guys? Who are their good guys?

Jane’s mission is to become a doctor. Her bad guys are anything or anyone that prevents her from studying—partying, good times, friends, and sports. Her good guys are anything or anyone that helps her to study and get good grades—parents, teachers, and authority figures.

Jack’s mission in life is to surf. His bad guys are parents, teachers, and authority figures. His good guys are partying, good times, friends, and sports.

Jack’s good guys are Jane’s bad guys, and his bad guys are her good guys!

We have a lot of tools now to read and interpret a person’s culture. As a summary, we can first look at a person’s systems of thoughts. For example, we can say that Jane belongs to a modern system of thought, while Jack belongs to a postmodern system of thought. Second, we can interpret a person’s culture by looking at their themes. For example, Jane’s values include honoring her parents, while Jack’s values include the importance of doing what you love. Similarly, we can look at where that person’s culture falls on the spectra between certain themes and counterthemes. For example, Jane belongs more on the group, private emotions, hierarchy, and control ends of the spectra. But Jack belongs more on the individual, public emotions, equality, and freedom ends of the spectra. Third, we can describe the person’s culture as a storyline: What is their mission, who are the bad guys and good guys, and what does a happy ending look like?

HOW TO CONNECT THE GOSPEL WITH A CULTURE

Now that we have interpreted both our culture and the other person’s culture, our next step is to connect the gospel with that person’s culture. This task is called contextualization. The task of contextualization is threefold: (1) interpreting the gospel, (2) communicating the gospel, and (3) applying the gospel to the hearers in their culture.16 The aim of contextualization is to have a dialogue between the cultures of the three major players in evangelism: our culture, the culture of the Bible, and the culture of our hearer. In doing so, we recognize the role of the three cultures in interpretation, communication, and application of the gospel.17

According to Timothy Keller, our strategy for contextualizing is to enter and challenge a culture with the gospel.18 If we only enter the culture, then we have overadapted our gospel because we have not challenged that culture with gospel norms. We have not been necessarily offensive with the gospel. We have let them do things they shouldn’t do and not asked them to give up what they need to give up. We have given them syncretism. This is what missiologists call uncritical contextualization.

On the other hand, if we only challenge the culture, then we have underadapted the gospel because we have not entered that culture. We have been unnecessarily offensive with the gospel. We have asked them to do things they don’t need to do and asked them to give up things that they don’t need to give up. We have given them legalism. This is what missiologists call colonialism, because we have imposed upon them our cultural norms as if they are gospel norms.

But if we both enter and challenge, then we have made the gospel understood in their language, metaphors, and idioms. We have challenged them with gospel norms. We have been necessarily offensive with the gospel. We have asked them to do things that the gospel asks them to do. We have asked them to give up things that the gospel asks them to give up. We have given them the contextualized gospel. This is what missiologists call critical contextualization.19

The Theological Justification for Contextualization

But how can we justify entering and challenging a culture? Many Christians have been brought up with a culture wars model in which the gospel is always in opposition to culture. So how can there be any connection between the gospel and human culture?

The Incarnation

“The Word became flesh” (John 1:14). The second person of the Trinity became a human who was enculturated. If the Son of God can enter a particular culture, our gospel can also enter a culture. But what should raise our eyebrows is this: John uses the term logos, translated “Word” in our English Bibles. Logos is an enculturated term with all sorts of culturally loaded meanings in ancient Greek culture. According to the ancient Greeks, logos was the organizing principle of the universe. To understand the shock of John’s using logos, this is the equivalent of a Star Wars geek saying, “The force became flesh.” Or a Chinese person saying, “The tao became flesh.”

The challenge of contextualization is the same challenge of translating the Bible from its original languages—Greek and Hebrew—into a contemporary language. Take, for example, John 1:14. How do we translate the Greek term logos? We could stick with the term logos, but now it is meaningless to a contemporary person. Or we could translate it into the English term Word, but now we pick up other meanings in the term word which John would not have intended. And so now we risk syncretism.

This is the challenge for those who translate John 1:14 into Chinese. If they use the term logos, it is meaningless. If they use the Chinese term for Word, then they have a word-for-word translation, but they don’t pick up the full meaning of logos. If they use the Chinese term Tao, as in “the tao became flesh,” then they have a similar meaning to logos. But they also risk picking up other meanings which are syncretistic with taoism.

This is the challenge of contextualization. If we don’t use the language, idioms, and metaphors of a person’s culture, then our message will be meaningless. But if we do use the language, idioms, and metaphors of the person’s culture, we may be understood, but we also risk syncretism with their culture. I believe that this is a risk worth taking. And it is the same risk that John took in John 1:14 when he used the term logos.

General Revelation

There is some knowledge of God that is universally available (Rom. 1:19–20). God reveals his truth to all humans, at all times, and in all places. Theologians have a saying: “All truth is God’s truth.” There is evidence of God’s truth in all human culture.

Common Grace

God’s goodness is universally available (Matt. 5:45). Richard Mouw suggests that God is glorified not only in salvation but also in his creation and beauty.20 This is why in all cultures we can find beauty in the arts, wisdom in the sciences, truth in other religions, and morality in their ethics. In this sense, “All goodness is God’s goodness!”21 Or we can add, “All beauty is God’s beauty.”

The Image of God (Imago Dei)

All humans are created in the image of God (Gen. 1:27). As a result, all humans share God’s creativity to create—or cultivate—worlds and texts of meaning. If there is a creation mandate in Genesis 1, there is a cultural mandate in Genesis 2.22 Thus, all cultures are expressions of our being in the image of God.

Eternity in Our Hearts

God has placed eternity in our hearts (Eccles. 3:10–11). To be a human is to carry a burden from God—a longing for eternity, wisdom, and understanding in the midst of God’s creation. Thus, every human has a God-given existential cry for transcendence, meaning, and eternity. And all cultures will find a way of expressing this cry.

Sin

All humans are sinful (Romans 1–3). As a result, every culture will also find a way of expressing its rebellion, idolatry, wandering, falleness, and suppression of the truth.

Analogies of Redemption

Creation groans for its redemption (Rom. 8:18–22). There is still some continuity between the present creation and the future new creation. Thus, there is also a conceptual link between creation and redemption.

This is why Jesus could explain the gospel with analogies from his culture: yeast, a mustard seed, a shepherd, a vine, a sower, and a wedding banquet. Paul also explained the gospel with analogies from his own culture: ransom, justification, and adoption.

This means that in every culture we should be able to find analogies we can use to explain the gospel. C. S. Lewis believed that God sent “good dreams” into the myths and stories of a culture. Don Richardson believed God planted redemptive analogies in a culture. And Brunner believed there is an Anknupfungspunkt (“contact point”) between the gospel and culture.23

THE PEACE CHILD

Don Richardson is the author of Peace Child and Eternity in Their Hearts. He believes that every culture has some story, ritual, or tradition that can be used to illustrate and apply the gospel.

Don Richardson and his wife, Carol, experienced this when they lived among the Sawi and learned their language. They found that the Sawi honored treachery as a virtue, so when Don told them the story of Judas betraying Jesus, the Sawi cheered Judas as the hero. How could Don and Carol possibly tell the gospel to people in this culture? What possible points of connection could there be?

Then Don and Carol found that the Sawi were often at war with neighboring villages. To make peace, the Sawi required a father in one of the two warring tribes to make an incredible sacrifice. He had to be willing to give up one of his own children as a “peace child” to his enemies. Peace could come because of a father’s sacrifice of his son.

The peace child was the redemptive analogy the Richardsons discovered in the Sawi culture. It was a point of connection to the gospel, and using this analogy, Don and Carol could speak of Jesus as God’s peace child to us.*

* Don Richardson, Peace Child: An Unforgettable Story of Primitive Jungle Treachery in the Twentieth Century (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Bethany House, 2005).

Our theological justification for contextualization is that we can enter any culture because of the incarnation of God’s Son and because of God’s general revelation, common grace, our creation in the image of God, and the promise that God has placed eternity in every human heart. At the same time, we should challenge all cultures with the gospel because all human cultures are affected by sin. And we have the language to enter and challenge because we believe that God has left a redemptive analogy in every culture, a means for communicating the gospel in a way that the people in that culture can understand.

But we should also be cautious in using analogies. We use them because they make our truth claim imaginable to people. Analogies don’t prove our truth claim—using analogies is not equivalent to using reason or evidence—but they make it more plausible that our truth claim is true. So it is helpful to recognize that redemptive analogies are a means and not the ends of our evangelism. Jackson Wu cautions, “If contextualization is constantly done by mere analogy, one can implicitly communicate two things: (1) the only thing that matters in the Bible is the information it takes to ‘get saved,’ thus short-circuiting genuine conversion and Christian growth, (2) the entire Bible is neither very important nor essential, thus implying that the revelation of God’s glory is not infinitely valuable. . . . By contrast, the desired goal [of contextualization] is worldview conversion.”24

For this reason, I believe that redemptive analogies by themselves will not be enough for us to communicate the gospel. By themselves they can seem trite or forced. We also need to connect the gospel to that culture’s existential cry and storyline. This is what we will explore both in the following section and in the next chapter.

A Method for Contextualization

Summing up all that we have considered to this point, a method for engaging in contextualization begins to emerge. I believe that we can start the work of contextualization by looking for any of the following points of connection between the gospel and our audience’s culture.

Find a Redemptive Analogy

Don Richardson found the “peace child” as his redemptive analogy. What is the redemptive analogy in our audience’s culture?

Find the Existential Cry

Every culture will find a way to express its God-given existential cry for transcendence, meaning, community, love, freedom, forgiveness, intimacy, uniqueness, connection, usefulness, approval, harmony, wisdom, and redemption.

Find the Storyline and Give the Gospel as the Happy Ending

Tim Keller suggests one way for integrating the gospel into a culture’s storyline.25 Every culture has a storyline that answers the big questions. How should things be? Why are things not the way they should be? What would set things right? Most of these storylines are on the right track because of God’s general revelation, common grace, our image of God, and our cries for eternity. The storylines are expressing a right, God-given desire. Often they correctly identify what is wrong with the world and what things should be like.

What we can do is enter and challenge the storyline and then show how only Jesus can give them the happy ending that they are looking for. The way we do this is by listening and trying to understand and empathize with the culture’s storyline. Then we can think about how to show people that they cannot have their happy ending the way they want by the way they are living. Finally, we communicate to them how Jesus gives them that happy ending. We can show them how Jesus gives them a far better ending than what they were wishing for.26

What does this look like? Let’s return to Jane and Jack. If you recall, Jane wants to go to Harvard and become a doctor. But what is Jane’s existential cry and storyline? Her existential cry isn’t to become a doctor. Rather, her existential cry is for security. Security is very important in the Asian-American culture, and becoming a doctor is one means of achieving this. And what is her storyline? Is it to become a doctor? No, it’s to achieve status in her family’s eyes and to bring honor to her parents, which will ultimately give her the sense of belonging she longs for in her community. Being a doctor is one of the means for her to achieve this.

So one way of telling the gospel to Jane is to use security, belonging, and honor as gospel metaphors. We can also identify her storyline, understand it, and empathize with it; she’s looking for security, and who of us doesn’t want this? But becoming a doctor will not guarantee security—there will always be another exam to take; there will always be another mountain to climb. But Jesus Christ promises us true security.

Jack wants to surf every day. But what is his existential cry and storyline? His existential cry is for freedom. Working as a laborer and surfing is one means of achieving this. And what is his storyline? Is it only to surf? No, it’s to find freedom—freedom from boredom, freedom to pursue pleasure, freedom to live life on his terms. Becoming a laborer and surfing is one of the means of achieving this.

So one way of telling the gospel to Jack is to use freedom as a gospel metaphor. We can also identify his storyline, understand it, and empathize with it; he’s looking for freedom, and who of us doesn’t want this? But working as a laborer and surfing will not guarantee freedom—there will be bills that he can’t afford, there will be a hierarchy of friends to impress, and there will be the ever-diminishing returns of pleasure. But Jesus Christ promises us true freedom. By giving him our lives, we gain it.

A Christian in Your Own Culture

We began with the example of youth pastor Adam. Adam thought he was giving Jane and Jack the gospel, but he was unknowingly giving them his midwestern American culture as well. What Adam needs to learn is not only the gospel but also how to read his own culture and the cultures of Jane and Jack.

Ever since the gospel went out from Jerusalem, the challenge has been to allow converts to be Christian and still be of their culture without converting to the culture of the evangelist. In the early church, the Jews wanted the Greeks to submit to Jewish cultural norms. But the council of Jerusalem (Acts 15) clearly resolved that the Greek converts did not have to submit to Jewish cultural norms. They could still be of their own culture.

The theological significance of the incarnation is that the gospel can be translated into any culture. If you are from a Vietnamese culture, you can be a Christian and still be Vietnamese. If you are from a Siberian culture, you can be a Christian and still be Siberian. And if you are from an indigenous Australian culture, you can be a Christian and still be an indigenous Australian. You do not have to become a white man to become a Christian!

The challenge for us when we evangelize is to translate the gospel into our audience’s culture. Jane, the high-achieving Asian-American, can be a Christian and still be a high-achieving Asian-American. And Jack, the Californian surfer dude, can be a Christian and still be a Californian surfer dude.

THE LONGING FOR REST

When I was a young medical doctor, I shared an apartment with some other young doctor friends. We were single, always moving from one hospital apartment to another, and very lonely. One night, one of my friends asked me what Christianity is all about. I knew that we both had an existential cry for rest, just to settle down in a place we could call home. So I told the gospel to him using rest as a chief gospel metaphor. I told him that being a Christian is being able to settle down with God in a place God calls home.

1. “[T]he Bible itself is not acultural, but it is transcultural,” David K. Clark, “Theology in Cultural Context,” in To Know and Love God: Method for Theology (Wheaton: Crossway, 2003), 120.

2. I owe this insight—that the contextualization is more than communication and application, but it is also interpretation of the Bible through a particular culture’s lenses—to Jackson Wu, Saving God’s Face: A Chinese Contextualization of Salvation through Honor and Shame, EMS Dissertation Series (Pasadena, Calif.: William Carey International Univ. Press, 2012), 10–68.

3. Hence the title of Peter Cha’s book, Following Jesus without Dishonoring Your Parents (Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity, 1998).

4. I owe this example to Clark, “Theology in Cultural Context,” 119.

5. Timothy Keller, “Contextualization: Wisdom or Compromise?” talk given at Covenant Seminary Connect Conference, 2004.

6. Keller, “Contextualization.”

7. This was Augustine’s view. And for a long time this was the view of the Christian church up until the Middle Ages. See the discussion in Megan Best, Fearfully and Wonderfully Made: Ethics and the Beginning of Human Life (Kingsford, AU: Matthias, 2012).

8. James Sire, The Universe Next Door: A Basic Worldview Catalog (Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity, 2004).

9. Simon Smart, A Spectator’s Guide to World Views (Sydney South, AU: Blue Bottle, 2007).

10. I owe this observation to my friend Timothy Silberman.

11. James Sire, Naming the Elephant: Worldview as a Concept (Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity, 2004).

12. Simon Smart gets this from Julie Mitchell, Teaching about Worldviews and Values (Melbourne: Council of Christian Education in Schools, 2004).

13. Kevin J. Vanhoozer, “What Is Everyday Theology? How and Why Christians Should Read Culture,” in Everyday Theology: How to Read Cultural Texts and Interpret Trends, ed. Kevin J. Vanhoozer, Charles A. Anderson, and Michael J. Sleasman (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker, 2007).

14. Paul Hiebert’s appropriation of Morris Opler’s “themes and counterthemes,” Emmanuel Todd’s demography, and Parson’s evaluative themes, in Paul Hiebert, Transforming Worldviews: An Anthropological Understanding of How People Change (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Baker, 2008), 26–27, 63–64.

15. Keller, “Contextualization.”

16. I owe this definition to Jackson Wu. Wu points out that most definitions—including my original definition—of contextualization are deficient because they talk only about the processes of communicating and applying the gospel to a particular culture. But contextualization necessarily also involves interpreting the gospel, because all of us come to the gospel with our culturally determined interpretive lenses.

17. Wu, Saving God’s Face, 10–68.

18. Keller, “Contextualization.”

19. Paul Hiebert, “Critical Contextualization,” Missiology 12 (1984): 287–96.

20. Richard Mouw, He Shines in All That’s Fair: Culture and Common Grace (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans, 2001), 36, cited in Vanhoozer, “What Is Everyday Theology?” 43.

21. Mouw, He Shines in All That’s Fair, 82.

22. Mouw, He Shines in All That’s Fair, 15–60.

23. C. S. Lewis, Mere Christianity (New York: Touchstone, 1980), 54; Don Richardson, Peace Child: An Unforgettable Story of Primitive Jungle Treachery in the Twentieth Century (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Bethany, 2005); Alister E. McGrath, Christian Theology: An Introduction (West Sussex, UK: Wiley and Sons, 2011), 167.

24. Wu, Saving God’s Face, 42 of 341, Location 928 of 11602, on Kindle.

25. Keller, “Contextualization.”

26. I owe this last observation to my friend Sam Hilton.