Mount Sinai – Jebel Musa, The God-Trodden Mountain, Mount Moses, Mount Horeb, the Holy Peak

I can’t believe Moses made this walk in sandals.

—BRUCE FEILER, Walking the Bible: A Journey by Land through the Five Books of Moses (2001)

* HIKING RULE 1: Moses may have made it in sandals, but he had divine assistance. Since you probably can’t rely on that type of backing, always invest in sturdy, waterproof boots with good ankle support, and never start a long hike with a new pair. Although modern lightweight boots tend not to require the break-in period that older, heavier versions did, you should still make sure you have used them on a few shorter walks to identify any potential rub spots or problems. Blisters and sore feet can quickly turn a glorious day of walking into nothing more than a painful endurance test.

The Jewish, Islamic and Christian traditions hold Mount Sinai to be the biblical mountain where Moses received the Tablets of the Law in the form of the Ten Commandments. The giving of this Covenant to the Chosen People is said to mark the true beginning of the Jewish nation.

Saint Catherine’s Monastery and the surrounding area is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Saint Catherine’s is the oldest remote monastic community to have survived intact. It has been used for its original function without interruption since the sixth century. UNESCO describes it as an outstanding example of human genius that “demonstrates an intimate relationship between natural grandeur and spiritual commitment.”

The view from the summit of Mount Sinai.

KENT KLATCHUK

This is a day hike with an altitude change of approximately 672 m, or 2,206 ft. The hike starts from just outside the monastery at 1600 m (5,249 ft.) and climbs to the top of Mount Sinai, which is 2272 m (7,454 ft.).

None, other than the usual risk of injury from turning an ankle or falling on the uneven steps and rocky path.

|

The mountain and the nearby Saint Catherine’s Monastery are located near the southern tip of the Sinai Peninsula, which is part of Egypt. |

|

Getting there: Cairo is the main access point. It is serviced by many major airlines or their partners, including, among others, Air France, British Airways, Emirates Airlines, KLM, Lufthansa, Royal Jordanian and Singapore Airlines. Egypt Air provides direct flights from Cairo to Sharm el-Sheikh. Bus service to the village of al-Milgaa (also known as Katriin), located about 3.5 km (2 mi.) from the monastery, (which is at the foot of the mountain), is available from Dahab, Nuweiba, Sharm el-Sheikh and Cairo. Many hotels in Dahab, Sharm el-Sheikh and Nuweiba can organize trips to the monastery and Mount Sinai. It is also possible to hire a taxi for the drive from nearby towns as well as from Cairo. |

|

Currency: Egyptian pound, or E£. E£1 = 100 piastres, or pt. For current exchange rates, check out www.oanda.com. |

|

Special Gear: if you are planning on climbing the Stairs of Repentance you will need good sturdy walking boots and plenty of water. Consider walking poles, since the stairs are rough and uneven. A headlamp or flashlight is essential, because you will probably be doing one way of the walk in the dark. Depending on the time of day, water, snacks and rented blankets to ward off the cold are available from small kiosks operated along the camel trail by the local Jabaliya people. |

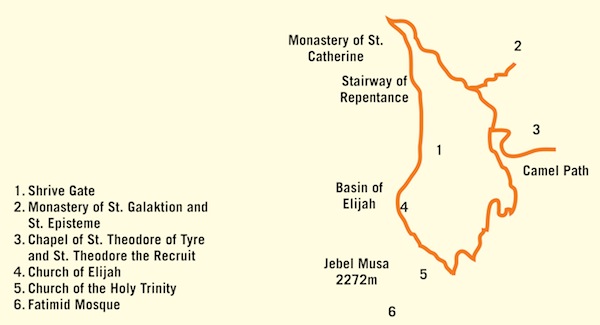

There are several alternatives for completing the hike up Mount Sinai, depending on the time of day you undertake the trek and whether you decide to watch the sun rise or set from the summit. Two well-defined routes exist: the camel trail and the Stairs of Repentance. Both trails meet just below the summit at Elijah’s Basin. From there, all hikers must climb the remaining 750 steps to the top.

As suggested by the name, it is possible to hire a camel to ascend the camel route to the basin, but the trail itself follows a relatively gentle slope and can be easily navigated by anyone capable of walking up a hill for about two hours. Most pilgrims and walkers take this path up before dawn in order to see the sun rise over the magnificent panorama of mountain peaks that can be seen from the top. Be sure to take a flashlight with you to navigate the trail in the darkness.

The Stairs of Repentance are rough and uneven and should only be tackled in the daylight. Many walkers will ascend the camel trail in the predawn darkness and descend via the steps after sunrise. There are approximately 3,000 steps to the basin, where the two trails converge, plus another 750 to the summit, so you need poles and strong knees to navigate this trail. Our group ascended the steps in the late afternoon, watched the sun set over the mountains and then descended in the darkness down the easy slopes of the camel trail. A flashlight or headlamp is essential when coming down. Of course, it is possible to do both trails in the daylight. This alternative allows you to see the impressive scenery both ways, but misses the climax view of the sun rising or setting while at the top.

Mount Sinai has been the site of Christian pilgrimage for centuries, a place where the devout still come to do physical penance as they toil up the Holy Mountain to be closer to God. But the God-Trodden Mountain has also been a magnet for tourists, naturalists and scholars for hundreds of years. They were, and continue to be, drawn by the prospect of a wild and desolate land of red granite and stunning topography that has changed little in thousands of years.

English naturalist Edward Hull, writing in the late 1800s, exclaimed, “Nothing can exceed the savage grandeur of the view from the summit of Mount Sinai,” while French diplomat, artist and historian Léon de Laborde, obviously awe-struck by the great and terrible wilderness spread out before him, declared, “If I had to represent the end of the world, I would model it from Mount Sinai.”

Hyperbole aside, no other place combines a trek to the top of one of the most sacred spots of three great religions with the chance to stay in and explore the oldest Christian monastery in continuous existence in the world.

Remember that Mount Sinai is located in the southern part of the Sinai Peninsula, which is essentially desert, so even in the summer it can be cold in the evenings. The Bible refers to the Sinai as “this terrible and waste-howling wilderness, a land of fiery snakes, scorpions, thirst” where the sun dominates the landscape.

The monastery is located at 1600 m (5,249 ft.). In July and August the mean maximum temperature at this elevation is 30°C (86°F) but can easily exceed this. Snow is not uncommon at higher altitudes by November. The best compromise if you are visiting other parts of Egypt, where the weather could be quite different than in the southern Sinai, is probably to stick with spring (March to May) or fall (September to October). I visited in January, and although there was no snow at the top, it was very cold, even during the day.

Mount Sinai is sacred to the world’s three great monotheistic religions: Judaism, Christianity and Islam. But while Jews and Muslims have no established custom of pilgrimage to the site, Christians have long felt the need to physically identify the actual Holy Peak that is so central to the biblical story of Moses.

As early as the third century, Christian ascetics identified this specific mountain as the “real” one, and began using it as a place to pray and come closer to God. In his book entitled Mount Sinai, Joseph Hobbs notes that Daniel Silver surmised the mountain’s identity was “probably based on little more than the vision of a desert monk … who had a revelation that this was the famous Mount Sinai where Moses had spoken with God.”

It is a statement the monks of Saint Catherine’s would no doubt strongly dispute. They believe with certainty that this is the true sacred mountain, based on the oral traditions of the local Bedouin and the existence, right from the beginning, of the Bible’s “burning bush.” In fact, the site that would eventually be occupied by the monastery at the foot of Mount Sinai was often called “the Bush.”

Scholars have pondered and debated the issue of the sacred mountain’s location for centuries, often undertaking arduous desert journeys to “prove” they found the Bible’s Mount Horeb and many of the other holy places associated with Moses’s journey.

One intriguing argument for the southern route to Mount Sinai focuses on three factors critical to survival in such a harsh environment. These include the availability of adequate water and pastures for the people and the herds, as well as the “bread from heaven” that God rained down each day to feed them as described in the book of Exodus. It is depicted as a “fine and flaky substance, as fine as the frost on the ground.” The Israelites called the bread “manna” and there is ample evidence of its existence along the route.

In the end, despite the identification of competing locations in the northern and central parts of the peninsula by many experts, this spot remains the favourite.

Whether you come as a pilgrim or an interested visitor, you have the opportunity to actually stay at the guesthouse located adjacent to the monastery. The food is plain but filling and the rooms are comfortable, with plenty of extra blankets and electric heaters to ward off the evening chill.

Remember you are in the desert, so expect it to be cold at night. In Walking the Bible Bruce Feiler recalls the warnings he had from former visitors to be prepared for the “coldest night of my life.” As a result he came armed with “enough equipment for Everest.” In the end he didn’t need it. Take it from someone who is always cold, I was also quite comfortable there, once we figured out the heater! There is also the option of staying at the nearby village of al-Milgaa (also called Katriin), which offers ample alternatives for all budget levels.

Mount Sinai looms behind Saint Catherine’s Monastery.

KENT KLATCHUK

Pressure from an ever increasing number of pilgrims and tourists has forced the monastery to restrict access in order to allow the monks to observe their own daily ritual of work and prayer. As a result it is open to the public from 9:00 a.m. to noon on most weekdays and Saturday, except religious holidays. Expect large crowds gathered at the gate and a press of people within the walls.

The Monastery of Saint Catherine on the God-Trodden Mount Sinai, as it stands today, is the oldest Christian monastery in continuous existence in the world. The walled monastery was not built until the sixth century, but we know a church and tower existed here in the fourth century based on the account of the Spanish nun Etheria (also called Egeria). During her pilgrimage to the holy sites in the area, she described “many cells of holy men there, and a church in the place where the bush is, which same bush is still alive today and throws out shoots.”

Tradition holds that the tower and church were built under the auspices of Saint Helena, after her son, the Roman Emperor Constantine the Great, made Christianity a legal religion in 313 CE. Consecrated as the Monastery of St. Mary, it was built as a refuge for the many monastics who were coming to pray at the site of the Burning Bush. The name recognized that, like the famous bush that was not consumed by the fire, Mary was a virgin who contained God and was not destroyed.

In the sixth century, the Roman emperor Justinian built the fortress that still exists today. Although he is said to have constructed the fortified monastery to protect the monks from warring nomads, he probably viewed the structure primarily as a defensive outpost. Once established at the site of the Burning Bush, it seems likely the rugged Mount Sinai that rises up behind it earned its permanent status as the biblical Mount Horeb almost by default.

The monastery was well known as a place of pilgrimage but did not begin to thrive until after 1000 CE when it became linked to the venerated Catherine of Alexandria.

The Romans built granite walls 18 m (60 ft.) high and 2.7 m (9 ft.) thick, as well as a basilica, the Church of the Transfiguration. The church doors are the oldest functioning ones in the world according to the monks.

The fact that the monastery has survived for over 1,500 years is a miracle in itself. Sheer isolation probably explains part of it, but a series of protectors over the years also helped ensure its continued existence. Arab, Crusader, Ottoman, French, British, Egyptian and Israeli armies have all left their mark on the peninsula but the monastery has survived, even thrived.

Legend maintains that the prophet Mohammed actually visited the monastery on one of his merchant trips. And in response to a request from a delegation of monks who visited Medina in 625 CE he granted the Covenant of the Prophet, ensuring protection of the Christian monks who had treated him so well during his stay. During Napoleon’s conquest in the late 1700s, protection was provided under a written proclamation that remains preserved at the monastery.

Still, the monks were not immune from attack. In fact for several hundred years and even into the twentieth century, visitors and monks alike gained access to the interior via a basket suspended on a thick rope from a pulley on the north wall. According to Feiler, the monks refer to it as the “first passenger elevator in the world.”

The monastery houses many treasures and should not be missed unless you are unfortunate enough to be there on a day when it is closed. About the size of a city block, it encompasses an incongruous collection of buildings, built at different times and connected by a maze of corridors and narrow passageways. Chapels, towers and monks’ cells are jumbled together with the Burning Bush, Moses’s Well, a library and a mosque. Much of the monastery is closed to the public but it is still possible to visit the Chapel of the Transfiguration and the Chapel of the Burning Bush as well as to view the actual bush and the well.

A recently restored museum, called the Sacred Sacristy, contains some of the monastery’s many treasures including examples of some of its world-famous Byzantine-era icons. The collection is recognized as one of the oldest and richest in the world, mainly because of a good piece of luck: its geographical isolation helped it escape the iconoclasm. (During the Byzantine iconoclasm, which began in 726 CE, Christian art depicting religious figures in icons was considered heretical and was largely destroyed.)

Over the centuries, the monastery has been a magnet for scholars coming to study its magnificent collection of religious manuscripts. With over 3,000 documents, the library is said to be second in importance only to the Vatican. Unfortunately, history has not been kind to the monks when it comes to the integrity of some of the researchers.

The most notorious example is that of Constantin von Tischendorf, who journeyed to the monastery in 1844 to study the Codex Sinaiticus. Dated from the fourth century, the codex is considered the oldest and most complete edition of the Bible, According to Janet Soskice in her book The Sisters of Sinai: How Two Lady Adventurers Discovered the Hidden Gospels, it predates most other known copies by close to 600 years. Written in Greek, it was a “magisterial Bible” too heavy to be carried by one man. Over the course of several visits, von Tischendorf managed to convince the monks to let him “borrow” the entire text.

Von Tischendorf promptly presented the codex as a gift to the Russian Tsar Alexander II and it was eventually sold by a cash-strapped Stalin to the United Kingdom in 1933 for £100,000. It now resides in the British Museum. Of course, the monks maintain the manuscript was only a loan and belongs back in their monastery.

One amazing story with a happy ending concerns the discovery of the Codex Sinaiticus Syriacus, one of the earliest known manuscripts in the world that preserves the text of the four gospels in Old Syriac. This codex resides in the monastery in a special box presented to the monks by the famous Sisters of Sinai. Their tale of scholarly sleuthing certainly proves the old adage that truth is often stranger than fiction.

Just outside the walls lie the monastery gardens. An oasis in a sea of barren rock and desolation, the gardens are fed by wells and a series of tanks that trap rain and snowmelt from the mountain. During her fourth-century visit, the nun Etheria talks of “a little plot of ground where the holy monks diligently plant little trees and orchards,” and even now peaches, almonds and olives thrive among the towering cypress trees.

In the midst of the garden is the ossuary, a stark reminder to all the monks of their ultimate fate. Soil is precious in this land of rock. So monks are interred in the small cemetery for a period of time. Their bones are then removed, washed and added to the rather grisly pile stacked in the charnel house. The empty grave awaits its next occupant.

Whether you believe this is the sacred Mount Sinai of the Bible or not, there is no denying that the rugged desolation of these “wild and tortured” peaks evokes powerful responses. Léon de Laborde, writing in 1836, described a “chaos of rocks,” exclaiming, “If I had to represent the end of the world, I would model it from Mount Sinai.” Edward Hull, in 1884, saw “the face of Nature under one of her most savage forms,” viewing it with “awe and admiration.” Suffice it to say that whichever route you decide to take, it will be well worth the effort. You will be rewarded with spectacular views of a “sea of petrified waves” in a jumble of red and purple hues stretching to the horizon.

The hike begins just outside the walls of the monastery. As noted in the “Hike overview” section there are basically two choices for climbing the mountain: the camel path and the Stairs of Repentance. Your choice will depend on the time of day you do the climb, whether you decide to watch the sun rise or set at the summit and the strength of your knees. Stairs, however, cannot be avoided. The two trails meet about 300 m (984 ft.) below the summit at Elijah’s Basin. At this point all hikers must climb the remaining 750 steps to the top. Don’t forget your flashlight, and take some warm clothes since it is almost guaranteed to be cold at the top.

A “sea of petrified waves” greets hikers nearing the summit of Mount Sinai.

WENDY FUNG

This is the easier but longer route. It begins immediately behind the monastery and follows a relatively gentle slope up the mountain to the basin. Anyone with reasonable walking ability should be able to navigate this path in two to three hours. It is possible to detour on two different side paths to see the Monastery of St. Galaktion and St. Episteme, where the nun Episteme and her husband (!), the monk Galaktion, came during the Roman persecutions, and the white Chapel of St. Theodore of Tyre. Since most people will do this trail in the predawn darkness, these chapels are generally bypassed unless you descend on the same path in the daylight.

This is the most popular route, so expect to be sharing it with many other climbers on their way to watch the sun rise. Along the way you will pass kiosks selling drinks and renting blankets to help with the cold and often fierce winds at the top. At the start of the trail, it is possible to hire camels which will take you to the basin, but that is technically cheating! From here everyone must navigate the 750 uneven steps to the summit. From the summit you have the choice of descending the same path or taking the Stairs of Repentance.

The rough, uneven steps of the Stairs of Repentance.

WENDY FUNG

Local Bedouins call it “the Path of Our Lord Moses.” It is the shortest, most direct route but definitely not easy. You should only consider doing this in the daylight, as the stairs are rough and uneven and dangerous to navigate in the dark. You will need extra water, since there are no kiosks along here until you reach the basin. Many people will climb the camel path in the darkness to see the sun rise and then descend the stairs. Either way, poles are essential if you value your knees. Our group ascended the stairs in the late afternoon, watched the sun set at the summit and then descended in darkness down the easy slopes of the camel trail.

The steep path begins southeast of the monastery. Tradition states that the stairs were carved by monks during the sixth century over a period of about fifty years. There are said to be 3,000 of them up to Elijah’s Basin (I lost count), but in 1836 de Laborde was sure it was 50,000! The monks hold that climbing the stairs provides the proper ritual preparation required to ascend the Holy Peak.

You will need to take your time going up. Far fewer people tackle this ascent, so you shouldn’t have to contend with the crowds that are common on the camel trail. Once our group had spread out and everyone found their own pace, I was struck by the profound, almost spiritual silence of the place, broken only occasionally by the sound of a dislodged rock as the hikers toiled upward. As you climb, look out for the so-called “Rays of God” in the rocks.

Over halfway up you will pass two stone arches. The lower one is called the Shrive Gate of St. Stephen. According to Hobbs, this is where St. Stephen “took pilgrims’ confessions and tested their knowledge of the Bible.” Those who passed the test were granted certificates and allowed to continue.

The two trails eventually meet at the Basin of Elijah, a welcome relief for weary stairway climbers. It’s a beautiful spot marked by a small chapel called the Church of Elijah and a towering cypress tree thought to be more than 500 years old. The deep green of the cypress provides a striking contrast to the barren landscape surrounding it. At the base of the tree a cistern called the “Well of Our Lord Moses” collects rain and snowmelt for the flocks of the local Bedouin, or Jabaliya, people.

The final ascent to the summit passes market stalls of the local Bedouin.

KENT KLATCHUK

From this point all hikers must climb the last 750 steps to the summit. They are steep, rocky and uneven, so take your time. If you are doing the hike to watch the sun rise, don’t be surprised if you have to pick your way around people who have spent the night huddled in sleeping bags to catch the first rays of the sun.

The actual summit area is quite small. Here the Christian Church of the Holy Trinity and a mosque cling to the rocks overlooking a stunning 360-degree panorama of barren, jagged peaks stretching to the horizon. It is not hard to understand why de Laborde thought it resembled the “end of the world.”

The Church of the Holy Trinity at the summit of Mount Sinai.

KENT KLATCHUK

The present church building dates to 1934, but a series of chapels are thought to have continuously occupied this spot since at least the fourth-century pilgrimage of the nun Etheria. After the “infinite toil” of her ascent, she speaks of visiting a church “not great in size,” but “great in grace.”

Because we did the hike to catch the sunset, and were there in January when it was freezing cold, we were lucky enough to have the entire site to ourselves. But it is not unusual for as many as two to three hundred climbers to be jostling for the best views while they eagerly await the sunrise.

Ironically, the monastery has extended its hospitality to pilgrims and visitors for centuries, but like many spectacular destinations that formerly could be reached only by an arduous journey, modern transportation and accommodation alternatives now make the site accessible for literally thousands. This has created tremendous pressure on the monks and their sacred mountain.

Bruce Feiler, in his book Walking the Bible, describes the crowded site at the top as an “ecclesiastical strip mall” filled with people, religious buildings and a Bedouin tent selling supplies. The monks and the local Jabaliya, who have a rich tradition of religious ritual dating back centuries, have been forced to stop the ceremonies that were becoming a “tourist spectacle” at the top of the mountain. The church and the mosque are now kept locked because visitors were sleeping and even defecating in them. It should go without saying that you are in a sacred spot, so please respect that fact.

One other word of caution before you begin the hike. If you are descending the camel trail in the dark as our group did, take note of the door where you need to re-enter the monastery. We wandered around in the inky darkness for some time until we finally stumbled on the entrance. Flashlights were of little use in the pitch black night, and believe me, no one heard our shouts for help through the massive stone walls. We were hoping someone would notice we had not returned for supper, but they were obviously too busy eating!

As noted in the section called “The essentials,” there are a number of alternatives available to access the site, including bus, taxi, private car or air. Many churches and religious institutions offer trips to Mount Sinai as part of a Holy Land tour. For those looking for a more in-depth experience that combines a visit to the mountain and the monastery with the chance to see more of this fascinating country, consider a small group trip that specializes in the region. This avoids the hassle of trying to organize something on your own. The language (spoken and written) as well as significant cultural differences (especially for women) can often create problems when it comes to negotiating details about service and payment (see the sidebar about baksheesh). It may be well worth it to leave the planning to the experts.

I have travelled with all three of these outfitters in various parts of the world. In my experience they are all reputable and reliable operators. Each company offers different hiking and sightseeing choices. I booked my 17-day Egypt and Jordan adventure with G Adventures and found it good value for money.

Arabic is the official language of Egypt. Unfortunately for most foreigners the script in which it is written has the appearance of an unreadable, if graceful, sequence of squiggles. Some form of transcription into words using the Roman alphabet would help, but apparently no single standardized system has yet been developed to do this. For those looking for a more complete guide, check out Lonely Planet’s Egyptian Arabic Phrasebook. Here are a few common phrases to get you started:

If you are this close, my unqualified recommendation is to consider a side trip to the rose-red City of Petra in nearby Jordan. You may know it from Steven Spielberg’s popular film Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, in which the famous Siq and Treasury had starring roles along with Harrison Ford in his quest for the elusive Holy Grail.

The hidden city of Petra was lost to history for centuries until it was “rediscovered” by the Swiss explorer Johann Ludwig Burckhardt in 1812 during a trip from Damascus to Cairo. (The city had fallen into obscurity after it was shattered by devastating earthquakes.) During his journey, Burckhardt heard rumours of some magnificent ruins located in the mountains of the Wadi Musa, the Valley of Moses. The location was a closely guarded secret, known only to local residents.

Burckhardt convinced his Arab guide to take him to the site by vowing to have a goat slaughtered in honour of Aaron, whose tomb lay at the end of the valley. In his journal he explains that “by this stratagem I thought that I should have the means of seeing the valley on my way to the tomb.”

His ploy worked, but the full extent of what he had stumbled across was not appreciated until after his death, when the inevitable flood of archaeologists, travellers and artists began visiting the site. Although excavations have continued since the nineteenth century, it is estimated that as little as 5 per cent has been uncovered.

Petra was probably occupied by the Nabataeans, a nomadic tribe who came from Arabia, around the early third century BCE. The tribe gradually established control over a vast region that eventually extended from the Hejaz of northern Arabia, the Negev and the Sinai to the Hauran of southern Syria.

Their fabulous wealth came from the taxes they imposed on camel caravans coming from the east and along the Incense Route from southern Arabia. By far the most profitable was the trade in frankincense, myrrh and other spices from Arabia, but the city was also an important link in the Silk Road.

With their expert knowledge of hydraulic engineering the Nabataeans were able to control water resources in the valley, building an elaborate series of dams, cisterns and channels. With secure access to water and the protective barricade of the surrounding mountains, they began building a magnificent city out of the rose-coloured rock (Petra means “rock”). They combined Greek and Roman design with their own unique local style to create an extraordinary place that is pure magic.

The multi-hued sandstone of the Siq with the channels of the water control system clearly visible along the side.

KENT KLATCHUK

Getting there is relatively easy from Mount Sinai. (Note that both the G Adventures and Exodus trips described in the “How to do the hike” section include Petra in their itineraries.) Bus service is available from al-Milgaa to Nuweiba, where excellent fast-ferry service departs for Aqaba in Jordan. From here, minibuses depart regularly for Wadi Musa (the town outside of Petra) with ongoing connections to various destinations in Jordan, including Amman. It is also possible to rent a car or hire a taxi from Aqaba.

Petra covers a huge area. You can spend days hiking around the site and never see it all. Specialized tours are available to help you do this; check out www.go2petra.com for information on all things Petra. In my humble opinion, here are a few highlights that should not be missed.

The Siq: You can’t really miss it, since you must walk down its length in order to gain access to the ancient city. It may look like it is the product of water erosion, but it was actually formed by tectonic forces that have split the rocks apart. The Siq winds for just over a kilometre past towering walls that sometimes almost meet overhead. The clever Nabataeans harnessed the floods that hit the narrow passage each winter and devised a water control system to supply the city. As you walk you will see the channels cut into the walls along with carvings hewn from the rock. The Siq seems almost mystical as it winds through the multi-hued sandstone and opens into the fairy-tale land of Petra.

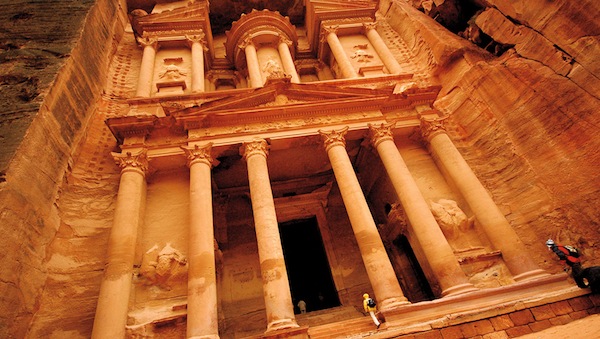

The Treasury of the Pharaoh, or Khazneh el-Far’un is probably the best-known monument in the city. The elaborately carved facade will take your breath away as you leave the twilight of the Siq and catch your first glimpse of it in all its glorious rose-coloured brilliance. There is no consensus on when it was built (probably near the end of the first century BCE), but the abundance of funerary symbols in its design indicate an association with the Nabataean cult of the dead. Wrested from the solid rock walls by men using little more than pickaxes and chisels, the level of craftsmanship is astonishing. Tradition holds that an Egyptian pharaoh hid his treasure in the urn in the middle of the second level. If you look closely you will see the solid-rock urn is pockmarked from bullets aimed at shattering it to reveal the gold inside.

The Monastery, or Al-Deir: One of the largest carved facades in Petra, it resembles the overall design of the Treasury, but dwarfs its famous counterpart in terms of scale. Its colossal size indicates the monument had some special significance. The monastery can only be reached by climbing an ancient stone pathway of more than 800 steps.

The climb is best done in the afternoon, when the stairs are in the shade. The trail starts behind the Nabataean Museum and is well worth the effort it takes to get to the top.

The elaborately carved facade of the Treasury of the Pharaoh.

KENT KLATCHUK

Egyptian food can generally be described as simple, hearty fare. Drawing on the traditions of its Greek, Lebanese, Turkish and Syrian neighbours, it has been adapted to suit Egyptian tastes with a focus on local ingredients.

Aysh, or bread, is the mainstay of the national diet. You will see freshly baked piles of it for sale every morning in markets all over the country. Along with the lowly bean, the two form the basic ingredients for some of the most popular street food in the country. Fuul combines slow-cooked fava beans mixed with garlic, lemon and spices stuffed into a shammy pocket (similar to pita bread). It is sometimes served with an egg for breakfast. Another popular variant called ta’amiyya (or falafel) is made with mashed broad beans mixed with spices, formed into patties and deep fried before they are tucked into a shammy pocket covered with tahini or sesame paste.

Coffee houses are ubiquitous. They are a gathering place for the locals, who come to sip strong tea or Turkish coffee and smoke the traditional shisha, or water pipe. The shisha has a glass tube filled with water, which cools the smoke and creates bubbles – hence the name “hubble bubble.” Hot coals plus the occasional puff keep the tobacco going. Smokers can choose from regular tobacco or various mixtures soaked in apple juice or other flavours such as strawberry or cherry, creating a wonderful aroma as the pipe is smoked. Before you indulge, make sure you get a disposable plastic mouthpiece to put over the end of the pipe.

Whatever epicurean adventures you decide to embark on during your stay in Egypt, here are a few words of caution and advice to help you safely on your journey.

Hygiene standards are often questionable or non-existent. If you decide to eat street food, be sure to have your hepatitis A shots up to date before you leave home, and never eat anything that is not thoroughly cooked.

As a rule of thumb, never eat raw fruit or vegetables you have not personally peeled or washed, unless you are eating in a top-class restaurant, and even then it might pay to be wary. Always be sure to check the seal on bottled water. If it is broken, do not take a chance on it.

Tipping is a way of life in Egypt. The practice is often called baksheesh, and you will be expected to tip for virtually any service you receive, real or imagined. In hotels and restaurants, a 12 per cent charge will usually be added to the bill, but beware. This doesn’t go to the waiter but straight into the restaurant till. You will still be expected to tip the waiter separately.

Vegetarianism – the concept is not well understood. Although it is easy to find vegetable-based dishes, including plenty of hearty bean soups, they will often be made with a meat stock, so it will be necessary to check if this is a concern to you.

Dining customs – as in any culture, there are certain subtle rules you should be aware of. For example, it is considered to be very bad manners to blow your nose in a restaurant or to eat, drink or smoke in public during the holy month of Ramadan. And it is generally advisable to sit next to a person of the same sex at the dinner table unless instructed otherwise.

There is a wealth of Sinai information available on the Internet. Here are a few reliable sites to get you started:

www.sinaimonastery.com is the official site of Saint Catherine’s Monastery.

www.egypt.travel, the official site of the Egyptian Tourism Authority, features news and a comprehensive range of resources and links.

www.sis.gov.eg, the Egyptian State Information Service, provides information on tourism, geography and culture as well as useful links.

www.go2petra.com has history and general information on Petra.

www.nabataea.net provides in-depth information on the Nabataeans.

You may have to search more than usual to track down books on Mount Sinai and the monastery. Most of these were located through my local library service:

Lonely Planet Egypt – I tend to be partial to the Lonely Planet series. This one is a comprehensive and useful starting point for planning any trip to Egypt.

Lonely Planet Jordan – another comprehensive and useful planning tool for any trip to Jordan.

Mount Sinai – Joseph J. Hobbs – a very readable and comprehensive view of the history, geography and biblical context, plus a great description of the monastery and the actual climb. By far my best resource.

Petra – Maria Giulia, Amadasi Guzzo and Eugenia Equini Schneider – another good one for the historical context, with wonderful photos, though somewhat academic.

Petra and the Lost Kingdom of the Nabataeans – Jane Taylor – a comprehensive source on the history of the fabled lost city, complete with lavish photographs. Taylor also has a shorter guide simply entitled Petra.

Saint Catherine’s Monastery, Sinai Egypt: A Photographic Essay – text by Helen C. Evans with photos by Bruce White – contains stunning photographs combined with good historical information.

The Hidden City of Petra – an A&E DVD that contains an excellent summary of the history and the sites.

The Monastery of Saint Catherine in Sinai: History and Guide – Jill Kamil – a fine overall guide to the monastery, including good maps and a detailed description of the climb.

The Pilgrimage of Etheria – edited by M.L. McClure and C.L. Feltoe – includes a portion of the narrative of Etheria’s pilgrimage to the “Mount of God” near the end of the fourth century. See archive.org for a scanned version of McClure and Feltoe.

The Sisters of Sinai: How Two Lady Adventurers Discovered the Hidden Gospels – Janet Soskice – tells the fascinating story of identical twin sisters who found and deciphered one of the earliest known copies of the Gospels at Saint Catherine’s Monastery. The tale sounds dry and academic but is really an astonishing story of grand adventure in the 1800s. Highly recommended.

Walking the Bible: A Journey by Land through the Five Books of Moses – Bruce Feiler. The chapters in Book III, “The Great and Terrible Wilderness,” offer the story of one man’s journey to the “god-trodden mountain of Mount Sinai.”