The name Yosemite is a corruption of an indigenous Miwok word for “grizzly bear” or “those who kill,” after the fierce Indian tribe inhabiting what came to be known as the Yosemite Valley. It has been spelled variously as “Yo-Hamite,” “Yohemity” and “Yo-Semite,” and it’s pronounced “Yo-sem-i-tee,” not “Yose-might”

The park is a paradise that makes even the loss of Eden seem insignificant.

—JOHN MUIR

* HIKING RULE 10: In his article “A Parable of Sauntering” published in 1911, early Sierra Club member Albert W. Palmer recalled John Muir’s advice on hiking (see box below). Muir maintained that “people ought to saunter in the mountains – not hike!” He explained that when people in the Middle Ages made pilgrimages to the “Holy Land,” they were going “à la sainte terre,” and so became known as “sainte-terre-ers,” or “saunterers.” Although his folksy approach to the etymology of “saunter” may make experts cringe, he surely got his point across. Muir believed that “… these mountains are our Holy Land, and we ought to saunter through them reverently, not ‘hike’ through them.” Measuring a trail in modern terms of distance covered in the least amount of time were foreign concepts to Muir, who was usually the last person into camp at the end of the day and who often “stopped to get acquainted with individual trees along the way.”

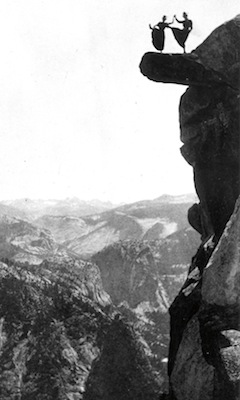

A stunning vista greets hikers near the start of the Panorama Trail.

D. LARRAINE ANDREWS

Designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1984, Yosemite National Park is described as a place of “exceptional natural and scenic beauty” that “vividly illustrates the effects of glacial erosion of granitic bedrock, creating geologic features that are unique in the world.” This glacial action over millions of years has produced a landscape of soaring cliffs, polished domes, hanging valleys, free-leaping waterfalls and sheer granite walls providing a spectacular backdrop for high alpine meadows, giant sequoia groves and over 300 lakes. Within the park’s 1,170 square miles (3030 km²), an elevation range of almost 11,000 ft. (3350 m) accounts for a wide diversity of ecological zones that are home to a stunning variety of plants and animals. Although it was not the first national park in the US, its far-sighted protectors developed the basis of the national park concept as it is known today.

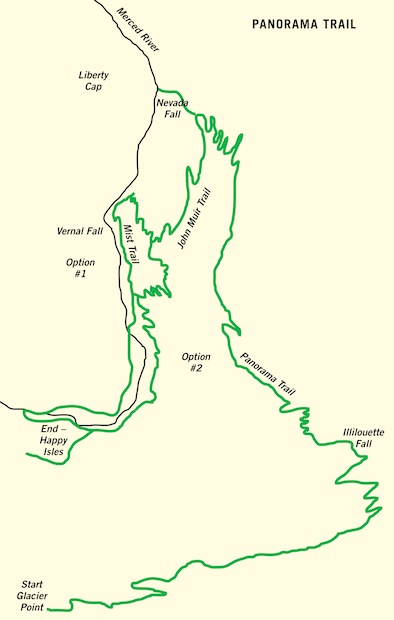

The Panorama Trail begins at Glacier Point at an elevation of 2200 m (7,200 ft.) descending to 1225 m (4,000 ft.) at Happy Isles on the valley floor. Although the trail is mostly down, it involves a climb of approximately 305 m (1,000 ft.) and a descent of 1280 m (4,200 ft.), for a net descent of 975 m (3,200 ft.) over a distance of 13.7 km (8.5 mi.).

As with any mountain hiking, the normal cautions regarding twisted ankles and injuries from falling apply here. However, the Panorama Trail does present its own particular hazard if you choose to take Option 1 down the Mist Trail. It is called the Mist Trail for a reason. Since it follows a steep descent over stone steps at the edge of Vernal Fall, the steps can be extremely slippery depending on the time of the year you are there. In the spring, when the fall is at full flow, expect to get drenched from the mist drifting over the stairs. Later in the season, the mist can be relatively non-existent and the steps almost dry. For anyone with vertiginous tendencies, you may consider taking Option 2, avoiding the stairs and the dangerous drop-off that is on your side as you descend. (See the Hike overview section for more details on these options.)

Although it is not normally an issue on the Panorama Trail, altitude sickness can create problems for hikers in other parts of the park, where trails can climb close to 4000 m (13,000 ft.). Classic symptoms include shortness of breath, fatigue, headaches and loss of appetite. If you experience altitude sickness, the only real fix is to descend to a lower elevation.

Visitors often assume bears are a big hazard, but there has never been a bear-related death recorded in the park. Perhaps not surprisingly, car accidents have been the biggest killers, of both bears and humans, followed by drowning, rock climbing, rock falls and suicide.

Although the California grizzly bear still graces the official state flag, the last known grizzly in California was killed in Sequoia National Forest in 1922. The only bears you will find in Yosemite are black bears. Just to confuse the issue, they aren’t always black, but often dark brown or cinnamon. Although they are highly intelligent and adaptable to pilfering a free meal if you make it easy for them, they will generally avoid any type of confrontation. That said, all bets are off if you happen to wander between a sow and her cubs, so stay alert.

|

Getting there: Yosemite is located on the western slope of the Sierra Nevada range in northern California. Four entrances provide a number of access alternatives for visitors: South Entrance off Highway 41 provides access to the closest airport at Fresno and the southern part of the state. Arch Rock Entrance off Highway 140 provides the most convenient access from northern California through the towns of Merced, Mariposa and Midpines. Merced is serviced by Amtrak (www.amtrak.com) as well as Greyhound (www.greyhound.com). From there, travellers can opt for a vehicle-free option by purchasing tickets through the YARTS system (Yosemite Area Regional Transportation, www.yarts.com), which provides daily bus service to the valley. Once in the park, a free shuttle service is available in the valley and seasonally along parts of Tioga Road. Full details are available in the Yosemite Guide, a free park publication that is widely available in print and online at www.nps.gov/yose. Big Oak Flat Entrance off Highway 120 on the west side of the park, provides the closest access to San Francisco, a four to five hour drive west of the park. Tioga Pass Entrance off Highway 120 on the east side of the park, provides seasonal access through the town of Lee Vining. The road is subject to heavy snow and is generally open only from late spring to early fall. As it leaves the park at an elevation of 3030 m (9,940 ft.) it follows a short, precipitous and quite spectacular descent of about 915 m (3,000 ft.) to the eastern desert at the base of the mountains. |

|

Currency: United States dollar, or USD, or US$. US$1 = 100 cents. For current exchange rates, check out www.oanda.com. |

|

Special gear: It is always advisable to have good, sturdy, waterproof hiking boots that are well broken in before you hit the trail. Hiking poles are helpful to maintain balance on uneven or slippery rocks or steps. Poles are particularly recommended on the Mist Trail, where the descent can be treacherous due to wet conditions. Of course you will also need to carry rain gear and adequate supplies of food and water. |

Kitty Tatch and Katherine Hazelston dance on Overhanging Rock at Glacier Point.

YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE LIBRARY

The Panorama Trail provides several different options, depending on how ambitious you are. In theory the hike can be done as a loop, but most people hike it one way from Glacier Point, at the end of Glacier Point Road, to the valley, which requires a ride to the trailhead.

If you are travelling with an outfitter, the details of getting to Glacier Point will be taken care of for you. If you are on your own, you will need to arrange a car shuttle or make a one-way reservation on the bus that runs mid-June to mid-September, departing several times a day from the valley. The bus is not exclusively for hikers, and since the viewpoint is very popular, you should reserve in advance to assure a place.

The trail is generally considered the most scenic of all the trails in the valley, (and arguably the entire park), with views of some of Yosemite’s most iconic images spread out in picture-perfect splendour all the way to the bottom. Hikers have several choices.

Option 1 is shorter and steeper, at 13.7 km (8.5 mi.). The final descent includes the Mist Trail, one of the most popular routes in the park. Although this portion can sometimes resemble “a trip to the mall,” it is worth it for the unsurpassed views of Vernal Fall.

Option 2, at 14.9 km (9.3 mi.), is longer but less steep, making it easier on the knees and avoiding the crowds often encountered on the Mist Trail.

Option 3 is the full loop, starting from the valley floor and climbing to Glacier Point on the steep Four Mile Trail, then descending the Panorama Trail to the bottom. Unfortunately, despite its name, the Four Mile Trail is actually 4.6 mi. (7.4 km) long! (All of these options are described in more detail under The Hike section below.)

Just one of the many superb views from Glacier Point.

COURTESY OF YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK ARCHIVES, MUSEUM AND RESEARCH LIBRARY

Because John Muir said so! In his book The Yosemite (1912), Muir advises anyone “so time-poor as to have only one day to spend in Yosemite” to start out at three o’clock in the morning (!) “with a pocketful of any sort of dry breakfast stuff, for Glacier Point, Sentinel Dome, the head of Illilouette Fall, Nevada Fall and the top of Liberty Cap…” Muir was famous for wandering the mountains for days with little more than a blanket, his notebook, some tea and a “crust” of bread tied to his belt. (Bread was important to Muir, who was serious when he wrote, “Just bread and water and delightful toil is all I need.” He was recounting his first summer in the Sierra, in 1869, when the party had run out of bread before new provisions arrived and had to rely on a diet of mostly meat. Almost a full six pages is given over to a discussion of camp food and the effects of a lack of bread on an unhappy stomach that “begins to assert itself as an independent creature with a will of its own.”)

Muir’s one-day excursion is basically the Panorama Trail with the Four Mile Trail and a “glad saunter” up Liberty Cap added in for good measure. This is described below, in the section on “The hike,” as Option 3 without the climb to the summit of the Cap. In typical Muir style, he advises hikers to linger at Nevada Fall “an hour or two, for not only have you glorious views of the wonderful fall, but of its wild, leaping, exulting rapids and, greater than all, the stupendous scenery into the heart of which the white passionate river goes wildly thundering, surpassing everything of its kind in the world.” Convinced yet?

The valley remains open all year, but the high elevation in the northern part of the park along Tioga Road means heavy winter snow generally restricts access from late spring to early fall. The park is famous for its dry, sunny summers, when you can expect huge crowds in the valley (complete with traffic jams) and waterfalls at a trickle or even dry. Springtime, when “the snow is melting into music,” with waterfalls running at their peak and meadows full of wildflowers, generally avoids the crowds but lingering snow usually means access to Glacier Point and Tuolumne Meadows remains restricted. Autumn is really the best time to visit. The summer hordes have finally left. The oaks, maples and dogwoods provide brilliant displays of fall foliage and the days are cool and crisp, making for almost ideal hiking conditions.

The most extravagant description I might give of this view to any one who has not seen similar landscapes with his own eyes would not so much as hint its grandeur and the spiritual glow that covered it. I shouted and gesticulated in a wild burst of ecstasy …

— John Muir, My First Summer in the Sierra

When Muir caught his first glimpse of the Yosemite Valley in 1869 it was already part of the Yosemite Grant, signed by President Abraham Lincoln in the midst of the Civil War on June 30, 1864. The grant entrusted the Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove of giant sequoias south of the valley to the State of California to be preserved for public use “for all time.”

Muir would eventually become one of the most eloquent advocates for the establishment of the park. But well before his arrival a few extraordinary visionaries, including Frederick Law Olmstead and Israel Raymond, had already begun a strong lobbying campaign that led to the enactment of the land grant. Their remarkable foresight, combined with the tireless efforts of John Muir, eventually resulted in the creation of the incredible wilderness sanctuary we now call Yosemite National Park.

And it all happened within a remarkably short time. As early as 1776, Spaniards colonizing the San Francisco Bay area wrote of a snowy range of mountains they christened the Sierra Nevada – sierra because the peaks were jagged and sawtooth, nevada because they were snowy.

The Spanish gave the mountains a name, but no white man would actually venture into the spectacular valley we call Yosemite until the arrival of the Mariposa Battalion in March 1851. Almost two decades earlier in 1833, Joseph Walker and his team of trappers met heavy snow as they climbed the east slopes of the Sierra Nevada. Walker later confirmed that he and his men knew of the existence of a great valley close to their route, but lack of food and supplies meant they were not equipped to explore it. Reduced to eating some of their horses, their main concern was survival.

What Walker and his crew didn’t know was that the valley was the territory of a Miwok tribe who had seen the white men pass their secret mountain home. They called the valley Ahwahnee, “the place of the big mouth,” because of its shape, and they called themselves Ahwahneechee, the people of that place. Walker’s failure to investigate the valley bought the tribe another 18 years of peace before disaster overtook them with the arrival of James Savage and his soldiers.

It was the beginning of what would be a very quick end to the Ahwahneechee way of life, in an astonishing series of events spanning a mere four years. In 1851 the valley was a secret stronghold known only to the natives. By 1855 they had all been killed or driven onto reservations and the first tourists had arrived.

Savage was commanding officer of the volunteer militia called the Mariposa Battalion, which the governor of California had authorized to deal with now hostile tribes in what became known as the Mariposa Indian War.

The conflict between miners, traders and native tribes had arisen following the discovery of gold in January 1848 at Sutter’s Mill on the American River northwest of Yosemite. With white men encroaching on their land and hunting their game without negotiation, the natives could be expected to retaliate. Following raids on two of his trading posts, Savage set out in search of a fierce tribe they mistakenly called the “Yosemetos,” an apparent corruption of the Miwok word “uzumati,” or grizzly bear. The name recognized their reputation as ferocious fighters.

Fortunately for us, a young recruit named Lafayette Bunnell, who accompanied the battalion, recorded his eyewitness account of the group’s discovery and subsequent naming of the valley in his book called Discovery of the Yosemite and the Indian War of 1851 Which Led to That Event. The first view came at a place he called Mount Beatitude, later named Inspiration Point. Bunnell describes his awe at the sight, admitting that “a peculiar exalted sensation seemed to fill my whole being, and I found my eyes in tears with emotion.” Bunnell seems to have been one of the only soldiers moved by what he saw. He wrote later in the book that “very few of the volunteers seemed to have any appreciation of the wonderful proportions of the enclosing granite rocks… ” One member recalled, “If I’d known that the valley was going to be so famous, I’d have looked at it.”

The group descended to camp near Bridalveil Fall. That night Bunnell suggested the valley be called “Yo-sem-i-ty” in recognition of the tribe they were effectively forcing out of this magical place. He felt the name was “suggestive, euphonious, and certainly American.”

By 1855 the first tourists were arriving to see the wonders of the valley for themselves. They were led by James Hutchings. A miner turned journalist with an entrepreneurial bent, he recognized the potential for promoting the grandeur of the valley in his new, illustrated California Magazine.

Hutchings was accompanied by artist Thomas Ayres, whose drawings were later used in books and articles published by Hutchings to promote the valley. Ayers was the first of many artists and photographers whose images would capture the imagination of the world.

Hutchings spoke of the “luxurious scenic banqueting” the valley offered and soon became the owner of Hutchings House, a hotel accommodating visitors willing to undertake the arduous journey to see these wonders. He actually employed John Muir for a season to build a sawmill. Hutchings, who was associated with Yosemite for close to 48 years, eventually grew to bitterly resent the growing popularity of his former employee, to the point where he refused to acknowledge Muir and his accomplishments in any of his writings.

To the south of the valley, Galen Clark had arrived that same year with the second tourist party. Clark returned in 1857, claiming land near the giant sequoia trees in Mariposa Grove. He had been diagnosed with a lung disease that he was told would shortly end his life. Clark decided to go to the mountains “to take my chances on dying or growing better, which I thought were about even.” His chances turned out better than even, as he spent most of the next 53 years in Yosemite, eventually dying there at the age of 96.

As travellers began arriving to see the “Big Trees” and to venture farther north into the valley, Clark became a reluctant innkeeper, guiding visitors through the marvellous wonders of the Mariposa Grove and stressing the need for protection of these centuries old giants. When the Yosemite Grant was made in 1864, Clark was appointed the first “Guardian of Yosemite.” He later became a friend of John Muir and a charter member of the Sierra Club. Muir described him as “the best mountaineer I ever met, and one of the kindest and most amiable of all my mountain friends.” It was high praise from a man who was certainly no slouch himself when it came to climbing mountains.

The arrival of tourists was soon followed by indiscriminate development – trails were built, forests logged, orchards and gardens planted. Sheep were moved to high alpine meadows where their sharp hooves destroyed the delicate wildflowers and fragile grasses.

In an unbelievably fortunate series of events, a few of the right people were in the right place at the right time with a shared vision that was unusual for the times. They saw the impending destruction of one of the world’s wonders and sounded the alarm to protect it.

Although John Muir’s name is forever linked with the formation of Yosemite National Park, his formidable legacy has overshadowed the contribution of several men who came before him. Without their initial foresight, who knows what would have happened to the precious treasure we know today as Yosemite.

Thomas Starr King was a Unitarian minister well known for his nature book The White Hills: Their Legends, Landscapes and Poetry, about the mountains in New Hampshire. In 1861 he set out to see if all the hype about Yosemite was warranted. He was quickly convinced. King chronicled his journey in a series of long letters that appeared in the Boston Evening Transcript, and trumpeted its wonders when he returned to his church in San Francisco. His letters created great interest back in New England, but his plans to create a companion book to The White Hills and use his influence to promote preservation of the valley were cut short by his untimely death just months before the Yosemite Grant.

King was followed in 1864 by Frederick Law Olmsted, the landscape architect who designed Central Park in New York City. He was overwhelmed with his first view of the valley, writing, “The union of the deepest sublimity with the deepest beauty of nature, not in one feature or another, not in one part or one scene or another, not any landscape that can be framed by itself, but all around and wherever the visitor goes, constitutes the Yo-Semite the greatest glory of nature.”

Olmsted teamed up with Israel Raymond, an influential San Francisco businessman who was concerned about the fate of the giant sequoias in Mariposa Grove. Raymond enlisted the help of US Senator John Conness (California), convincing him to introduce a bill in Congress to transfer Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove to the State of California “for public use, resort and recreation … for all time.” The bill passed in 1864, unchallenged by a government totally preoccupied with the bitter Civil War being waged in the east.

The creation of the Yosemite Grant was an improbable and unprecedented victory in a time when the concept of conservation and the preservation of wilderness based solely on its natural and inherent beauty was totally foreign to most people.

It may have represented an historic milestone, but it soon became obvious that protection was in name only. Government appropriations for improvements were almost non-existent, while the administration of the grant lands degenerated into a quagmire of mismanagement and “fat cat” appointments to the governing board. Uncontrolled development resulted in a hodgepodge of roads and hotels, and pastures full of cattle and sheep.

Muir had once written that he wanted “to entice people to look at Nature’s loveliness.” But he admitted it was not an easy task, noting in 1890 that “… the love of Nature among Californians is desperately moderate.” It seemed Californians’ love of profit was putting any love of nature at serious risk. Muir had left Yosemite in 1874 to explore the Sierra Nevada, marry, and raise a family on a fruit farm acquired from his father-in-law, with only occasional visits to his beloved Yosemite. His wife eventually sold some of their lands to allow him to return to his first loves of exploration and the study of nature.

A sightseeing trip in 1889 with his friend Robert Underwood Johnson was a catalyst for action. Muir had not seen the valley since 1884. He was dismayed and sick at heart to see thousands of “meadow mowers” destroying the pristine grasslands of Tuolumne Meadows. “To let sheep trample so divinely fine a place seems barbarous,” he wrote.

Johnson, the influential editor of Century Magazine, convinced Muir to take on the challenge of promoting the formation of a national park to protect the wilderness areas surrounding the land grant. His magazine provided Muir with a national platform to conduct a campaign in which he wrote some of his most enduring and evocative prose in support of the new park. The power and passion of his writing were clearly evident when he wrote: “But no temple made with hands can compare with Yosemite. Every rock in its walls seems to glow with life … as if into this one mountain mansion Nature had gathered her choicest treasures…” Muir’s and Johnson’s efforts were instrumental in the designation of Yosemite as a national park on October 1, 1890.

Magnificent views of Half Dome are revealed along the fire-scarred hillside.

LISA P. FREEMAN

But another challenge loomed. The valley and the Mariposa Grove remained under state control and they were in bad shape. By 1895 Muir was in despair, noting, “It looks ten times worse now than … seven years ago. … As long as the management is in the hands of eight politicians appointed by the ever-changing Governor of California, there is but little hope.”

Hope did come, however, in the person of President Teddy Roosevelt, who visited Yosemite in 1903. Incredible as it may seem now, Muir and Roosevelt camped out together in the real Yosemite for several nights. Under Muir’s persuasive guidance, Roosevelt was convinced of the need to protect this special place and on June 11, 1906, following bitter resistance by Yosemite businessmen, a bill was finally passed to transfer the Yosemite Grant lands to the national park.

Muir wrote in triumph to his old friend Robert Johnson: “Sound the loud trimble and let every Yosemite tree and stream rejoice… ” In the years to come, the park would face, and continues to face, many challenges, not the least of which is its incredible popularity. It regularly attracts close to four million visitors every year. But thanks largely to the incredible persistence and dedication of John Muir, the marvels of this “mountain mansion” are protected forever.

The Panorama Trail is normally done as a one-way hike beginning at Glacier Point and descending to Happy Isles in the valley. As described in the “Hike overview” section, if you are travelling on your own, you will need to arrange a car shuttle to Glacier Point or take the bus that runs from mid-June to mid-September. It runs several times a day from the valley, but seats should be reserved in advance. It is not exclusively a hikers’ bus and is very popular with tourists who take the round trip tour. Check the free park publication called the Yosemite Guide for information on the shuttles and practically everything else you need on park essentials.

If you are travelling in your own vehicle, Glacier Point is reached by taking the signed junction along the Wawona Road and driving 25 km (15.5 mi.) to the end of Glacier Point Road. The “Hike overview” section describes three hiking options. Options 1 and 2 follow the same path until you reach the turnoff for the Mist Trail. Option 2 provides a longer but gentler descent, but you can decide when you get there how your knees are doing. Option 3 is basically the loop described by John Muir for hikers with one day to spend in the valley. (See the “Why would I want to?” section above.) This route makes for a long hiking day, adding another 7.4 km (4.6 mi.) to the total and requiring a strenuous climb of 975 m (3,200 ft.) up to Glacier Point, with the views at your back. The good news is it is mostly downhill after that as you follow the Panorama Trail to the valley floor. If you choose Option 3, the trailhead is below Sentinel Rock on Southside Drive at road marker V18. All three options end at Happy Isles in the valley, where you can take the free shuttle back to Yosemite village.

Once you have reached Glacier Point and taken some time to absorb the spectacular view in front of you, head to the Panorama Trail signpost near the snack bar. The route follows a fire-scarred hillside that is regenerating from a 1987 natural fire. Head left at the fork.

Spectacular vistas along the track make it clear why it is called the Panorama Trail. Note the “Giant Staircase” formed by Nevada Fall and Vernal Fall as they plunge in two major steps from Little Yosemite Valley.

LISA P. FREEMAN

Mules are still a common sight on the trail at the top of Nevada Fall.

D. LARRAINE ANDREWS

As you descend, magnificent views of Half Dome open up on your left. This Yosemite icon will be visible in all its glory from many places along the trail, clearly revealing the fact that it is not actually a dome, but a ridge.

The trail is clearly marked and easy to follow as you descend a series of switchbacks to Illilouette Fall with more views of Half Dome and Mount Starr King. You will descend to a wide bridge and then begin the only major climb on the trail, following the slopes above Panorama Cliff. It soon becomes clear why it is called the Panorama Trail as vantage points along the track provide stunning vistas from Upper Yosemite Falls east past Royal Arches, Washington Column and North and Half Dome. Just when you think it can’t get any better, more views of Half Dome, Mount Broderick, Liberty Cap, Clouds Rest and Nevada Fall come into view.

The trail eventually switchbacks down about 1.6 km (1 mi.), intersecting with the John Muir Trail. Make sure to take the short spur to your right and the Nevada Fall viewpoint, a perfect lunch stop.

Once you have enjoyed the spectacular views from the top, head back to the John Muir Trail. On your right, Nevada Fall thunders into the valley. The trail can be slippery (I speak from experience here), so take your time on the descent. Soon you will reach Clark Point and decision time. From here you can head right along a connector trail to descend to the Mist Trail (Option 1) or stay on the slightly longer but gentler John Muir Trail (Option 2), which is largely viewless from this point but less steep and much easier on the knees. (It can be quite dusty, though, since it is also a horse trail.) Both trails end at the Happy Isles bus stop, where you can catch a free shuttle back to Yosemite Village.

Assuming you turn right at Clark Point, you will soon pass a sign for the Upper Mist Trail. Ignore this and descend to a viewpoint at the top of Vernal Fall. Then veer south and walk up along the fence to a gate-like opening where you turn right to enter the lower half of the Mist Trail. The trail is one of the most popular in the park, so expect crowds. In the spring it can be quite treacherous, as mist from Vernal Fall saturates the steep steps and you as well. In the autumn the steps can be relatively dry. Portions of this trail are among the steepest in the park, so just take your time on the descent and stop to enjoy the view along the way. There is a steep drop off on your side of the steps by the fall, so if that could be a problem for you, consider taking the safer John Muir Trail.

Muir described Vernal Fall as “a staid, orderly, graceful, easygoing fall, proper and exact in every movement and gesture, with scarce a hint of the passionate enthusiasm of … the impetuous Nevada, whose chafed and twisted waters hurrying over the cliff seem glad to escape into the open air…” As usual, he seems to have nailed it.

His description of tourists could have been written for the Mist Trail too: “Up the mountains they go, high heeled and high hatted, laden … with mortifications and mortgages … , some suffering from the sting of bad bargains, others exulting in good ones …” Expect to see everything from people in dress shoes to flip-flops, with tiny babies strapped to their backs or three-year-old children running amok on the steps. Just take your time and try not to knock anyone over the edge! The trail eventually descends to cross the Vernal Fall bridge and continues on down to the shuttle-bus stop at Happy Isles and free transportation back to Yosemite village.

Yosemite is extremely hiker friendly, with an abundance of information available for anyone who wants to plan their own adventure. Guided day hikes and overnight backpacking are also available through organizations closely associated with the park, including the Yosemite Conservancy, the Sierra Club and Delaware North, the park’s concessionaire. (See the “Internet resources” section below for more details.)

If you have at least a week to devote to exploration and want the chance to hike in different parts of the park without the need to camp or organize everything yourself, consider booking with an independent operator who can make all the arrangements so all you need to do is hike. Here are a couple of ideas to consider. I have hiked with both these operators. They are highly reputable and offer excellent value for money. I did the six-day Yosemite trip with Timberline, which covers a variety of hikes around the park, from easy to strenuous, including the Panorama Trail.

The park is full of place names attributed by various explorers and early settlers, often reflecting the Spanish and American Indian influence on the language. Here are a few interesting ones:

Yosemite, it seems, can only be described in superlatives and none of them seem to be entirely adequate. But while much of the focus tends to be on its crown jewel of the valley, there is plenty more to explore outside this narrow and spectacular sliver. The park is the size of Rhode Island, with 95 per cent of it designated wilderness and not accessible to cars. With over 1300 km (800 mi.) of trails, you could literally spend years exploring. Fortunately, even in the valley, the number of people on the trails tends to decrease quickly once you get past the one or two kilometre mark. Ask five Yosemite veterans about their favourite hike and you will get five different answers. It is impossible to say. Here are a few alternatives to consider.

Clouds Rest: A strenuous hike of 23.3 km (14.5 mi.) return, climbing to a 360-degree panorama of the park, with awesome views of Half Dome and the valley. The trail begins at the Sunrise Lakes trailhead off Tioga Road at the west end of Tenaya Lake and is well marked. It involves an elevation gain of 541 m (1,775 ft.), 305 m (1,000 ft.) of which occurs over the course of about 1.6 km (1 mi.) up a series of rocky, ankle-busting switchbacks. Although the hike only tops out at 3025 m (9,925 ft.), I experienced altitude problems on this hike, probably because it climbs so quickly. Acrophobics and klutzes beware. Anyone who can’t handle heights, narrow ledges and sheer drop-offs should not plan on completing the final short bit of this hike to the very top, but you will still be rewarded with good views on the ridge. Muir writes of running up to Clouds Rest to get some primulas for a botanist friend, then running home in the moonlight with the sack of roses on his shoulder!

The vista from Clouds Rest provides outstanding views of Half Dome, El Capitan and the Yosemite Valley.

LISA P. FREEMAN

Mono Pass: A moderate high-altitude hike of 12 km (7.5 mi.) return that climbs past streams and meadows to the historic Mono Pass. Be sure to continue a further 500 m (0.3 mi.) into the Ansel Adams Wilderness for fantastic views of Mono Lake and the desert to the east. I would vote this my favourite High Sierra hike but there are many more that I haven’t done, of course. The trailhead is located off Tioga Road, just 1.6 km (1 mi.) west of the Tioga Pass entrance and is well marked. The hike is one of the highest-elevation day hikes in the park, topping out at 3230 m (10,600 ft.) with an elevation gain of 275 m (900 ft.). Although it is higher than Clouds Rest, the climb up is gradual and I had no altitude problems. You will pass two forks along this hike. Keep to the left at both. Muir’s description of his climb over Mono Pass to the shores of the Lake in My First Summer in the Sierra is worth a read, as he describes in great detail the trees and the wildflowers “in lavish abundance.”

Glen Aulin: A moderate hike of 21 km (13 mi.) return. Parking is available at the trailhead near the stables close to Tuolumne Meadows off the Tioga Road. This is a very pretty hike as you head past Soda Springs and Parsons Lodge, following the river and the meadows, meandering through lodgepole pine forests and over white burnished granite worn smooth by glaciers. The trail eventually descends steeply to a wonderful lunch spot by the White Cascade. The Glen Aulin High Sierra Camp is just over the bridge if you want to partake of the toilets. From here, it’s uphill most of the way back, with an elevation gain of 180 m (600 ft.).

Glacier-sculpted rocks are clearly visible along Glen Aulin Trail.

D. LARRAINE ANDREWS

Mariposa Grove: Located at the south end of the park, this may be out of your way, but try not to miss the chance to wander amongst the giant sequoias. It’s not hard to understand how Ellsworth Huntington came to think of them as old friends.

Food outlets in the park tend to offer standard American fare that is often overpriced but usually provides good fuel before or after a hike. In the valley, the Mountain Room Restaurant at Yosemite Lodge at the falls and the pricey dining room at the Ahwahnee Hotel both offer stunning views along with excellent food. The historic Wawona Hotel, close to the Mariposa Grove in the south of the park, is also a good bet for an upscale meal.

Hygiene standards are high and there should be no concerns about food establishments within the park.

Tipping is expected. Normally at least 15 per cent of the bill would be considered reasonable.

Vegetarians will find no strictly meatless establishments, but most places will offer a vegetarian option.

There is a vast amount of information related to Yosemite available on the Internet. Here are some reliable sources to get you started:

www.nps.gov/yose is the official park website maintained by the National Park Service.

www.yosemite.ca.us/library includes thousands of pages of digital books and articles.

www.sierraclub.org includes a feast of everything related to John Muir, including his complete books and many essays and articles. The Sierra Club also offers guided day hikes and backpacking trips.

www.yosemiteconservancy.org, dedicated to park preservation, offers guided hikes and backpacking trips.

www.yosemitepark.com is the official website of the DNC Parks & Resorts at Yosemite, the park’s concessionaire. Reservations for camping and lodging can be made here. They also offer guided hikes and backpacking trips.

www.yosemitepark.com is an excellent source for trip notes and maps.

There have been hundreds of books written about Yosemite and the Sierra Nevada. A good place to look is the website for the Yosemite Online Library as well as the Sierra Club noted above. Following is a list of books with which I am familiar from my research:

Complete Guidebook to Yosemite National Park – Steven P. Medley – award winning, if a little dated now; gives a concise overview on the basics of the park.

Lonely Planet: Yosemite, Sequoia and Kings Canyon – full of practical information on everything you need to know about the park, plus good maps and hike descriptions.

My First Summer in the Sierra – John Muir – the classic tale of Muir’s 1869 trip herding sheep in the high Sierra.

The Secret of the Big Trees: Yosemite, Sequoia, and General Grant National Parks – Ellsworth Huntington – a fascinating piece on climate change research done in the early 1900s. A free copy can be accessed at www.archive.org.

The Yosemite – John Muir – another classic about the park.

Yosemite, a National Treasure – Kenneth Brower – a lavish National Geographic park profile with the text and photographs we expect from National Geographic.

Yosemite and the Range of Light – Ansel Adams – Adams at his best.

Yosemite and the Wild Sierra – Galen Rowell – a collection of some of Rowell’s best images.

Yosemite National Park: A Complete Guide – Jeffrey P. Schaffer – a very comprehensive guide on hiking in the park, including over 80 detailed hike descriptions, chapters on history, flora and fauna, geology and a great bibliography.

Yosemite: The Complete Guide – James Kaiser – an excellent guide to the park, its history and its hikes, with great maps and outstanding photographs by the author.

Yosemite: The First 100 Years 1890–1990 – Shirley Sargent – just what it says: a good history of the park, with lots of archival photos.

Yosemite Trivia – Michael Ross – the answers to all your questions about Yosemite.

Yosemite’s Yesterdays, Volumes I and II – Hank Johnston – a fascinating collection of stories about the park that weren’t necessarily the biggest newsmakers but certainly merit a read. Includes many wonderful archival photos.

A chubby marmot enjoys the sun.

SANDY BRENNAN