Milford Track takes its name from the famous Milford Sound, located at the north end of the trail. The sound was originally named Milford Haven by Captain John Grono in 1809 after its Welsh namesake in Pembrokeshire.

“The Finest Walk in the World”

—The Spectator (London), 1908

* HIKING RULE 4: Always carry a supply of newspaper in your pack. It works better than a drying room for wet boots.

The view down the Arthur Valley to Lake Ada.

ULTIMATE HIKES, NEW ZEALAND

Since the early 1900s the Milford Track has claimed to be “The Finest Walk in the World.” The trail is located in Fiordland National Park, part of the Southwest New Zealand World Heritage Area. The region is known to the Ngai Tahu tribe as Te Wahipounamu, the place of greenstone. In addition to Fiordland, the area incorporates Aoraki/Mount Cook, Westland/Tai Poutini and Mount Aspiring National Parks. Covering 2.6 million hectares, or about 10 per cent of New Zealand’s land area, it is considered one of the great wilderness regions of the southern hemisphere and a place of exceptional beauty.

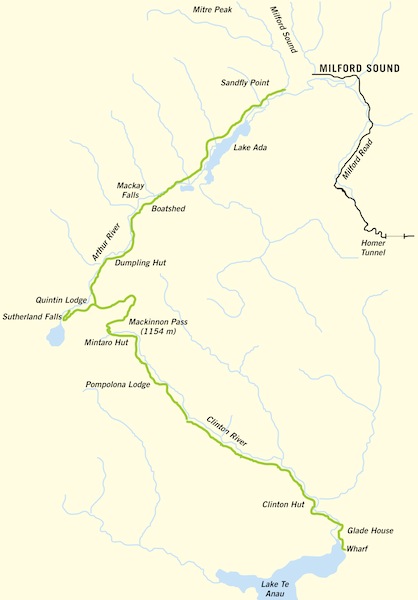

The trail covers approximately 54 km (33.5 mi.) and must be walked one way, from south to north. You can walk as an independent backpacker, carrying all your gear, or with a private outfitter, staying in comfortable lodges along the track. If you choose the lodge option, you will still need to carry a pack with clothes and personal items from lodge to lodge. The trail begins at the north end of Lake Te Anau, climbs to a maximum altitude of 1154 m (3,786 ft.) at the top of Mackinnon Pass and ends at Sandfly Point, close to the entrance to Milford Sound.

None, unless you are afraid of getting wet. Unlike neighbouring Australia, there aren’t even any poisonous snakes or spiders to worry about. Of course, there is always the risk of falling or turning an ankle on rocky or uneven terrain.

|

Getting there: The country is serviced by a number of major airlines or their partners, including Air New Zealand, Air Canada, United Airlines, Qantas, American Airlines, Cathay Pacific, Air China, British Airways and Lufthansa. |

|

Currency: New Zealand dollar, or NZD, or NZ$. NZ$1 = 100 cents. For current exchange rates, check out www.oanda.com. |

|

Special gear: Make sure you have good, sturdy, waterproof walking boots. Hiking poles are also highly recommended. Although there is much of the track where you may question why you have them, they will be particularly useful on the day you climb Mackinnon Pass and make the steep descent on the other side. Since this hike is done over four days, you will need a 40-litre backpack if you are hiking from lodge to lodge. If you are going as an independent hiker, plan on a 60-litre pack to carry all your food and utensils in addition to clothes. And of course, a hat, sunscreen and water bottles are essential. But arguably the single most important piece of equipment will be your rain gear. Average annual rainfall along this trail is close to 8 m (26 ft.), so unless you get extremely lucky, you will get wet at some point. (See “The hike” section for a more detailed discussion of gear.) |

|

A note on spelling: Various sources use a confusing array of spellings for personal and place names. I have relied on the spelling conventions in John Hall-Jones’s Milford Sound: An Illustrated History of the Sound, the Track and the Road. The book was by far the most readable and informative single source on the area that I found. |

Just so you know, in New Zealand you are a tramper going on a tramp, not a hiker on a hike.

There are basically two options for doing the hike. You can choose to go as part of a guided walk, with accommodations and meals provided in comfortable lodges, or as an independent walker staying in Department of Conservation (DOC) huts along the route. The guided walk is offered exclusively through Ultimate Hikes. (See “How to do the hike” for more details.) The trail is highly regulated by the New Zealand government, with access limited to 40 independent walkers and 50 guided walkers per day. Bookings are required months in advance to ensure a spot.

The track must be walked from south to north over four days. Because of the booking procedure it is necessary for hikers to keep moving even in extreme weather, which can happen at any time of the year. Adequate gear to handle anything, from snow to strong wind to heavy rain and flooding, is critical. During periods of heavy flooding, DOC evacuations by helicopter may be required.

Access to the trail is via water on both ends, beginning at the north end of Lake Te Anau and ending at Sandfly Point, where you will need to catch the boat across to Milford Sound. The walk basically follows the Clinton River, then climbs Mackinnon Pass, descending into the Arthur Valley and out to Milford Sound along the Arthur River and Lake Ada.

The hike isn’t easy, nor is it particularly difficult. Children must be at least 10 years old, while people over 70 may be asked to provide evidence of their health and fitness. There is one long day requiring a climb of close to 500 m (1,640 ft.) up Mackinnon Pass followed by a steep descent into the Arthur Valley of more than 800 m (2,625 ft.) over rocky and uneven terrain.

You need to wrap your head around the possibility that you may have to walk in water up to a metre deep for more than a few steps – so no, you won’t be able to keep your boots dry. Once you have done this and are confident you have the gear and fitness to handle it, then try to put this worst-case scenario out of your mind and concentrate on why thousands of trekkers have flocked to this famous trail for well over a century.

As New Zealand poet Blanche Baughan wrote, “To tell the truth, you get so often wet through on the track that you take no notice of it, and the air is so pure and germless that you never take any harm, either.” The bottom line is you are going to see some of the most pristine wilderness anywhere in the world, a combination of rain forest, snow-capped peaks, glacier-carved valleys and rivers so pure you can still safely fill your water bottle along the way.

In 1908 Blanche Baughan wrote an article for the London Spectator that she titled “A Notable Walk.” But, as she later explained in the preface to an expanded 1926 booklet version, the responsibility for the title change to “The Finest Walk in the World” rested entirely with the editor. She reasoned that the Spectator was a “journal celebrated much more for considered moderation than for any leaping enthusiasms, … so that I think we of New Zealand may venture to accept the distinction without any fear of boasting.” And so the moniker has stuck for over 100 years.

Baughan tends to wax poetic (she was a poet, after all), with the flowery descriptions common to her time, declaring, “this track anyone possessing feet to walk with, eyes to see with, and a love for Nature at her loneliest and fairest, could scarce do better than essay,” concluding, “From the variety, the beauty and the scale of the scenes through which it passes, it must certainly be accounted one of the most glorious natural wonders of the world.”

Whether the walk is the world’s finest or not, it certainly qualifies as one of the world’s natural wonders. Expect to see an incredible diversity over the trail’s relatively short distance as you pass from magnificent beech forests to the subalpine scrub and tussocks of the pass to the ferns, mosses and lichens common on the Arthur River. Along the way you will be greeted by a rich variety of birds, rugged peaks and the sounds and sights of cascading waterfalls. Maybe Baughan wasn’t so over the top after all.

The track is open from late October to mid-April. Since the yearly average rainfall is close to 8 m (26 ft.) you can expect a lot of rain, even at the height of the summer months. Just prepare to get wet and then enjoy the added beauty of instant waterfalls falling in torrents down the sheer cliffs of the mountains.

The story of the track begins in Milford Sound when a lone Scottish adventurer landed on the shores of the deep fiord on December 1, 1877. Early that morning he had left his camp farther south on Thompson Sound, making the trip of almost 100 km (62 mi.) in ten hours. In his diary he congratulated himself, noting, “I don’t want to sound my own trumpet too much, but this is a bully run for a man in an open boat in ten hours.”

The man was Donald Sutherland. He came in search of his fortune, convinced the area would yield gold, greenstone (jade), rubies and asbestos. Although he never found any material wealth, he found his roots in this most remarkable place, remaining here for over forty years and eventually earning the name of “the hermit of Milford Sound.”

Of course the earliest human history of the area goes back much further, to the Maori, who called the place Piopiotahi after the now extinct thrush-like piopio bird. They came to hunt eel and to collect the rich deposits of greenstone, or takiwai, they found at Anita Bay at the entrance to the sound. The precious stone was transported over what we now know as Mackinnon Pass and then by waterway to Lake Te Anau and beyond. The soft, translucent takiwai was favoured for making fine-quality ornaments and jewellery.

The first European connection was a Welsh sealer named Captain Grono who had worked the Fiordland coast as early as 1809. He gave the sound its original name of Milford Haven after a town close to his home in Wales. By an odd coincidence, he was followed in 1851 by another Welshman who lived close to Milford Haven: Captain John Stokes in HMS Acheron. Perhaps Stokes was homesick as he filled his charts with Welsh names for many of the peaks, rivers and points around the sound.

Stokes was charged with surveying the west coast sounds. Of all the inlets they had seen, Commander Sir George Richards declared that Milford, “in remarkable feature and magnificent scenery, far surpasses them all.” Its “Alpine features and its narrow entrance,” with “stupendous cliffs which rise perpendicular as a wall from the water’s edge to a height of several thousand feet, invest Milford Sound with a character of solemnity and grandeur which description can barely realise.”

Little has changed since Richards recorded his first impressions of the sound so long ago. The wild and brooding cliffs still rise in vertical walls from dark waters full of dolphins and seals. When it rains, the entire sound is a magical place of cascading waterfalls plunging down sheer, rocky precipices.

No doubt Commander Richards would be astounded to know this pristine wilderness now draws close to half a million visitors each year, most of them flocking here over the Milford Road during the peak summer months of January and February, while over 14,000 trampers make the trip over the Milford Track. The place is easily one of the country’s most famous tourist destinations, and there is a reason it was called the Eighth Wonder of the World for many years.

The sound became a popular stop for cruise ships as early as 1874, but at considerable cost for visitors. The New Zealand government soon realized the tourism potential for the sound if an overland route could be found for trekkers.

Mount Balloon rises from the mist at Mackinnon Pass.

NEW ZEALAND DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION

Meanwhile, Sutherland had been busy building his “City of Milford,” complete with streets, a flag mast and a stone pier. He called his three-roomed hut the Esperance Chalet, described by one visitor as “neat and tidy.” Sutherland had been joined by John McKay to prospect the area. They knew the government in Queenstown was interested in finding a direct route to Milford Sound, so with £40 cash and six months supplies from the Council, they set off to explore.

In November 1880 the two discovered McKay Falls and the famous three-leap Sutherland Falls, which they claimed were the world’s highest. At the upper end of the Arthur Valley they came upon a looming peak they named Mount Balloon “because it was sticking up out of the mist like a balloon.”

Once news of the spectacular falls leaked out to the world, Sutherland soon found his “splendid isolation” constantly invaded by cruise ship tourists asking him to guide them up to have a look. Since most of them came from the city and seemed to have some pretty silly questions, Sutherland often called them “ashfelters.” He and his wife Elizabeth eventually built a guesthouse called the Chalet, accommodating up to 300 trekkers each season. Known as “The Mother of Milford Sound,” Elizabeth stayed on at Milford after her husband’s death in 1919, running the Chalet until she sold it to the Tourism Department in 1922.

In 1888 Charles Adams, the chief surveyor of Otago, commissioned Sutherland to cut a track up to the falls (for the grand sum of £50) while Quintin Mackinnon was offered £30 to hack out a trail up the Clinton Valley from the head of Lake Te Anau. Mackinnon had built a log cabin at Garden Point on the western shore of Lake Te Anau in 1885 where he worked at Te Anau Downs Station in the busy months. According to Mrs. Katherine Melland of the Station, “He came to this lovely, beautiful lake to forget and be forgotten.”

Mackinnon certainly wasn’t forgotten. Not only did he discover the pass to connect the Clinton and Arthur Valleys, but he forged the track up the Clinton Valley in atrocious conditions that would have stopped most men dead in their tracks. On September 7, 1888, Mackinnon and his friend Ernest Mitchell set out on their journey. He described it as “fearful work.” Continual rain meant they were unable to light a fire and cook or dry out their tents. As rations ran low they were reduced to one meal a day.

Finally they pushed through to the pass on October 16, eventually making their way to Milford Sound where he wrote in Sutherland’s visitors’ book, “Found good available track from Te Anau to connect with Sutherland’s track. Found Government maps very much out and the Hermit’s very much in.” Finally, a viable track had been found.

Mackinnon became the track’s first guide, famous for his fried scones. On an 1891 guided trip, William McHutcheson described “Mac” as “a stout broad-shouldered Scot, every lineament of whose bronzed and weather-beaten face spoke of determination, endurance and dogged perseverance under difficulties.”

A memorial cross on Lake Te Anau commemorates Quintin Mackinnon’s death.

ULTIMATE HIKES, NEW ZEALAND

Tragically, Quintin Mackinnon’s whale boat Juliet was found submerged in Lake Te Anau after he was reported missing in 1892. He was presumed drowned but his body was never found. A memorial cross was placed close to the spot where the boat had been discovered and is passed by the ferry on the journey up the lake to Glade Wharf and the beginning of the track he wrenched from the wilderness.

It would take years of building and upgrading to develop the track that exists today. Constantly at the mercy of flooding, wind and avalanche, the track, huts and lodges are a still a challenge to maintain today.

The publication of Baughan’s 1908 article in the London Spectator prompted even more demand for tourist facilities as walkers flocked to see “The Finest Walk in the World.” The opening of the Milford Road in 1953 finally provided vehicle access to the sound, opening the floodgates to tourists from around the world.

Started in the depression years of the late 1920s as an employment project, the road wasn’t officially opened until 1954 when the famous Homer Tunnel, under the formidable obstacle of the Homer Saddle was finally completed. Men worked with pickaxes and wheelbarrows to carve out the highway and the 1270 m (4,167 ft.) long tunnel.

The road was built from both ends, with the tunnellers working from the Homer side piercing through to the Milford end in 1940. Construction ceased during the war, and in 1947 the unfinished tunnel was opened to track walkers doing the round trip. This marvel of engineering is now a paved World Heritage highway winding its way through lush forests and rugged mountains from Te Anau to the stunning vistas of Milford Sound.

As noted in the “Hike overview” section, there are basically two options for completing the tramp. You can choose to join a guided tour with accommodations and meals provided in comfortable lodges or you can walk as an independent hiker staying in designated DOC huts along the route. Camping is not allowed.

The track is highly regulated by the New Zealand government, with access limited to 40 independent walkers and 50 guided ones each day. This may sound like a prescription for disaster, resulting in crowded trails and the potential for a less than optimal hiking experience. But the fact is that the use of one-way travel (the track must be hiked from south to north over four days), and a careful segregation of guided and independent hikers in strategically placed lodges, huts and rest stations along the way, means the trail can often seem quite deserted. I recall walking in solitary contemplation several times, with not a hiker in sight and only the sound of the river and the bellbirds for company. There was never the slightest hint of congestion anywhere along the trail, even with 90 of us tramping along each day.

I chose to do the guided hike. It is extremely well run, with excellent accommodations and meals provided in each of the lodges. There is no shortage of fresh Kiwi cuisine to keep you fuelled, and each “wilderness” lodge is equipped with comfortable beds, hot showers and some serious drying rooms.

Expect full hot breakfasts and three-course dinners as well as a welcoming afternoon cuppa tea on your arrival off the trail each day. Each morning you will build your own lunch from an enormous selection of options. (Fresh supplies are regularly delivered with military precision by helicopter, so there is never any shortage of food.) Ultimate Hikes also supplies four guides who spread out along the trail and offer excellent commentary on flora and fauna along the way. For added safety, there is always a sweep at the back to make sure no one gets left behind.

You will need to carry all your personal clothes and rain gear plus lunch each day. A 40-litre pack is suggested. Ultimate Hikes can supply a backpack plus a heavy-duty raincoat and pack liner if required.

Unlike some backpacking trips in a foreign country, the logistics of doing the walk as an independent tramper are not difficult. In typical Kiwi style, the huts are very well run. Each has gas rings for cooking, coal or gas stoves for heating, tables, basins, bunk rooms with mattresses, flush toilets and a drying room. Hut fees are included in your permit, which you must obtain from the DOC well in advance.

You will still need to carry all your food and cooking utensils in addition to your clothes and rain gear. Plan on a pack capacity of at least 60 litres. If the cost of the guided hike is too rich for your budget, this is certainly a doable option. Just be prepared to miss a few nights sleep due to the inevitable snorers sawing logs next to you.

Please note: Day-to-day descriptions are based on the guided walk option.

Glade House and the swing bridge across the Clinton River.

ULTIMATE HIKES, NEW ZEALAND

Independent – Te Anau Downs to Clinton Hut – 5.0 km (3.1 mi.)

Guided hikers will join the group in Queenstown for a bus ride to Te Anau Downs and the ferry ride to Glade Wharf at the north end of Lake Te Anau. Independent hikers must make their own way to the boat launch to catch the ferry. (See the “How to do the hike” section below for logistics details.)

Today is an easy introduction to the magnificent scenery that is the trademark of every kilometre of this trail. The sheer mountain peaks and lakes of Fiordland were carved out over two million years by massive glaciers during the last ice age, which ended just 14,000 years ago. The rivers of ice scoured the landscape, forming vertical-sided U-shaped valleys and lakes like Te Anau, the country’s second largest.

Hikers disembark at Glade Wharf for an easy stroll through southern beech forest to Glade House. Set in a clearing on the east bank of the Clinton River, the first Glade House was built in 1895 by John and Louisa Garvey. It soon became a place for walkers to stop before beginning the walk.

The Garveys were well known for their hospitality. With their 11 children, they established a tradition of evening entertainment for guests. The original building burned down in 1929 but was rebuilt in 1930. Although the house was linked to Milford with a telephone line, the service was often out of commission from avalanches and wind damage. The Garveys kept carrier pigeons as well, though, and their “pigeon post” proved quite reliable.

As you walk in, expect to be greeted by a frequent and unwelcome visitor. The pesky sandfly (a.k.a. blackfly) thrives here and unless you keep moving or use a strong repellent, they will be your constant companion over much of the trail.

It seems sandflies are nothing new to the landscape. Maori legend has it that the goddess of the underworld released them to forever keep men from living here, because the land was so beautiful. And as far back as 1773, Captain James Cook remarked on them in his journal during his exploration of the Fiordland coast, noting, “The most mischievous animals here are the small black sandflies, which are very numerous and so troublesome that they exceed everything of the kind I ever met with.”

Lush beech forest along the Milford Track.

ULTIMATE HIKES, NEW ZEALAND

Independent – Clinton Hut to Mintaro Hut – 16.5 km (10.2 mi.)

The day begins with a walk over the swing bridge that spans the Clinton River. You might be lucky enough to spot black eels and rainbow trout as you cross. The trail heads into lush beech forest along the river, with a chance to spot blue ducks and hear the clear, fluid notes of the tui, or parson bird, and the bellbird. Soft, feathery ferns are common, as are fuchsia trees with their purplish-red flowers. A short detour to the Wetland Walk is well worth the time. The boardwalk features interpretive panels as it crosses moss wetland and offers spectacular views up the valley to Mount Sentinel.

For a few kilometres the track follows the old, flat packhorse trail, then heads up along the west branch of the Clinton Valley until it meets the debris from a major avalanche in the 1980s. The rubble blocked the river, forming a lake where dead trees emerge ghostlike from the water. This portion of the track passes through a number of avalanche paths, so be sure to watch for sign posts. According to the DOC, there are 56 such paths along the track, which can cause delays or make the track impassable at any time.

Guided hikers stop for lunch at the Hirere Falls shelter, with a view to the falls across the valley. Not far down the trail, Mackinnon Pass comes into view on the skyline. It looks ominous but in fact the gradient is not much steeper than some you have already climbed.

The track passes Hidden Lake, then heads back into beech forest until it emerges onto the Prairie, a grassy flat with good views of the ice-capped peaks. Guided hikers then head on to Pompolona Lodge. The name comes from “a sort of fried scone” that Quintin Mackinnon often made for his guests. Apparently he sometimes caused dismay when they saw him toss candles into the frying pan to make his famous concoction until people realized the candles were made of mutton fat!

Once the lights are out and quiet descends, you might hear the shrill whistle of the nocturnal and flightless kiwi bird – a two-note call that sounds like ki-wi.

Independent – Mintaro Hut to Dumpling Hut – 14.0 km (8.7 mi.)

This is the toughest day of the walk, with a climb of close to 500 m (1,640 ft.) to the top of Mackinnon Pass, followed by a steep descent of more than 800 m (2,625 ft.) over rocky, uneven terrain. Although most people worry about the ascent, many agree that coming down is probably the hardest part of the track. It requires concentration and a slow, steady pace. Here is where your poles will pay off big time. Your knees will thank you.

The trail crosses a swing bridge and passes a small, grassy clearing, the remains of a paddock for the packhorses that supplied the huts. Numerous avalanche zones are traversed and hikers should not stop in marked areas. Soon Practice Hill heads up to Lake Mintaro, and the first of the well-graded zigzags (a.k.a. switchbacks) signals the beginning of the climb to the summit. As you follow the 11 zigzags you will pass from a canopy of beech trees to subalpine shrubland to alpine tussock grassland. On a clear day, superb views of Mount Balloon and Nicolas Cirque unfold, but don’t forget to watch for the wonders at your feet – like mountain daisies, bluebells and Mount Cook lilies, the world’s largest buttercup.

Pass Hut and the toilet with the best view in Fiordland. Mount Wilmot is on the left and Mount Balloon looms on the right.

NEW ZEALAND DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION

As you near the summit, you will pass the Quintin Mackinnon memorial cairn, honouring the discovery of the pass by Mackinnon and Mitchell in 1888. Now all your effort pays off with spectacular vistas down the Clinton and Arthur valleys and the surrounding ice-covered peaks. Enjoy the view but don’t get too close to the infamous 12-second drop. (That’s how long it would take you to hit the bottom if you went over the edge.) A series of small tarns or ponds dot the landscape as you head for lunch at Pass Hut and a chance to use the toilet with the best view in Fiordland. From your seat a well-placed window enables you to visually retrace your steps back down the length of the Clinton Valley.

The trail ahead flanks Mount Balloon, then begins the long steep descent to Quintin Lodge. Along the way, stop to admire what are arguably some of the best views the trail has to offer. Hikers will be directed by markers and their guides down the emergency track at times of high avalanche risk – usually spring and early summer. Our group descended via this detour, which is steeper than the main track but shorter. You will know you are close to the end when you glimpse Lindsay Falls and Dudleigh Falls. One final steep section brings you to the swing bridge over Roaring Burn (Gaelic for stream or creek) and the welcome prospect of afternoon tea at the lodge.

But you’re not done yet! Enjoy the break, and then rally yourself for the 4 km (2.5 mi.) side trip to Sutherland Falls, a pleasant hike through fine silver beech and fuchsia forest. Just a word of warning: there is one steep section to climb, so if your knees are screaming “No,” remember there will be a good view of the falls (albeit from a distance) on Day 4 after you leave Quintin Lodge.

Sutherland Falls.

ULTIMATE HIKES, NEW ZEALAND

Independent – Dumpling Hut to Sandfly Point – 18 km (11.2 mi.)

This distance is actually longer than Day 3, but the walking is easy with plenty of the spectacular scenery you have come to expect. As you pass the 20 mile peg, be sure to look back for one last glimpse of Sutherland Falls. Soon Racecourse Flats is crossed – a straight section where packhorses once got competitive – then on to the Boatshed Shelter for morning tea. The shelter was used to house the boat used on Lake Ada to ferry passengers and luggage.

Boardwalks and more bridges eventually lead to a short side track to McKay Falls and the curiously eroded Bell Rock. Blanche Baughan’s 1926 book The Finest Walk in the World sums it up this way: “MacKay Fall [sic]: no Sutherland, but still a glorious outburst of music and bright white light upon a world of green shadowiness and silence … This is one of the loveliest woodland scenes in the whole walk.”

And I would have to agree. The higher rainfall and milder temperatures in the Arthur Valley foster lush vegetation with ferns, mosses and lichens in abundance. Today’s trail has some of the best beech forest on the track, along with fine mountain and valley views.

Along Lake Ada you will pass a section blasted out of the sheer rock wall by track builders in 1893, while the broad, easy path at the end is thanks to the “efforts” of a less than enthusiastic crew of 45 prisoners who had arrived in 1890 to “cut the Te Anau road.” The project was abandoned as a dismal failure after less than 2 km (1.2 mi.) had been completed in two years.

Sandfly Point marks the end of the track. A shelter here keeps those pesky bugs at bay while you wait for the ferry to take you to Milford. As you wait for your comfortable ride, spare a thought for the early trekkers. Until the Homer Tunnel was opened to trampers in 1947, people had to turn around and do the whole track in reverse back to Te Anau!

Guided hikers enjoy a celebratory dinner at Mitre Peak Lodge on the evening of Day 4 before embarking on a cruise of the famous Milford Sound on Day 5 and a bus ride back to Queenstown.

Independent hikers must arrange their own accommodations in Milford and transportation back to Te Anau or Queenstown. (See the “How to do the hike” section for more details.) The cruise prior to departing is highly recommended.

Option 1, guided hike: Must be booked through Ultimate Hikes, www.ultimatehikes.co.nz. The trip starts and ends in Queenstown. Air New Zealand provides regular air service between Queenstown, Auckland, Wellington and Christchurch. (See the “Consider this” section for more information on Queenstown.)

Option 2, independent walker: Permits must be purchased through the DOC. Booking details are available at www.doc.govt.nz. Hikers must catch the ferry across Lake Te Anau to Glade Wharf at the village of Te Anau Downs. There is limited accommodation in the village, but you can use the town of Te Anau as your base. The town is the main starting point for a number of tramps throughout the region, with numerous options for accommodations and tramping supplies. Te Anau does not have an airport, but regular bus service is available from Queenstown, plus shuttle service to the ferry wharf at Te Anau Downs as well as from Milford Sound back to Te Anau or Queenstown at the end of the trek. Check www.greatwalksnz.com for bus information and www.realjourneys.co.nz for ferry information. The hike ends at Sandfly Point. Hikers must catch the ferry to Milford at designated times and make their own way back to Te Anau or Queenstown.

There is no denying that Kiwis have a distinct lingo all their own. For example, did you know that if you are going “across the ditch” you are going across the Tasman Sea to Australia, or that you are not cool if you are “daggy”? One particular expression that stumped me for a while was the ubiquitous “sweet as.” For the longest time I thought it had an extra “s” tacked on the end, making it somewhat rude. I finally discovered it is an all-purpose term that means “great.”

To the untuned North American ear the accent may sound similar to their Australian neighbours, but don’t make the mistake of suggesting that to a local.

New Zealand has two official languages – English and Maori – and the latter is enjoying a resurgence as the Maori strive to preserve and promote their culture. You will notice that government departments have been given Maori names and many place names use both the English and Maori versions.

In fact, the use of Maori greetings is becoming more common. Here are a few you might want to try out:

Queenstown tends to be the jumping-off point for anyone planning on tramping the Milford Track. The first white people arrived in the area in the mid-1850s to establish sheep farms. The peace and quiet of the pastoral life was soon shattered in 1862 when two sheep shearers, Thomas Arthur and Harry Redfern, discovered gold on the Shotover River. The discovery triggered a stampede as thousands headed there in search of fortune.

Soon a mining town sprang up on the bay, complete with hotels and all the amenities required to cater to a population that quickly grew to over 8,000. There are several variations on how it was named, all revolving around the statement that it was considered “fit for a queen,” hence Queenstown. Although the river yielded record amounts of gold, it had petered out by 1900 and the number of residents dropped to less than 200.

It wasn’t until road and air access began to improve in the 1950s that the spot started to become a popular tourist destination. Set on the pristine shores of Lake Wakatipu with the Remarkables mountain range soaring up on its doorstep, the town has become a four-season “Global Adventure Capital.” If you can’t find anything to do here, you need to seriously reconsider your travel expectations.

The Remarkables soar above Queenstown and Lake Wakatipu.

CHIHARU KITAI, NEW ZEALAND DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION

Activities include everything from bungee jumping, jetboating, whitewater rafting, canyoning and paragliding to mountain biking, skiing, snowboarding and zorbing (rolling down a hill inside a transparent plastic ball). You can tramp and climb to your heart’s content on nearby trails that rate from easy to challenging, all within a short distance of downtown. If that sounds too exhausting to contemplate after hiking the Milford Track, the town offers many slower-paced alternatives.

One of the most popular choices is the Skyline Gondola, offering a spectacular panorama of Queenstown, the lake and the mountains. A number of walking trails can be accessed close to the gondola, or you can pass on the gondola and hike up to the top. I opted for this alternative on a gloriously clear day. From the trailhead on Lomond Crescent, take the upper, left-hand gravel track. The hike is steep in places and takes one to 1.5 hours. Once you’ve hiked up, you don’t need to feel guilty about taking the gondola back down.

You won’t have any worries about being limited to mutton and boiled vegetables here. Kiwi cuisine embraces the best of local fresh ingredients, from tender lamb to seafood specialties such as greenshell mussels, clams and scallops to local produce straight from the field. Food styles have been highly influenced by Pacific Rim and Polynesian neighbours, so expect a fusion of tastes and ingredients. New Zealanders like their food, and every little café and restaurant seems to offer a tantalizing array of choices.

Hygiene standards are very high at the lodges on the Milford Track, and in fact there is no cause for concern when eating out anywhere in New Zealand.

Tipping is considered optional. Unlike North America, where workers depend on tips for part of their income, this is not the case in New Zealand. It is entirely up to you if you choose to reward good service.

Vegetarians: There may not be a large number of strictly vegetarian restaurants but most menus will offer a vegetarian option.

There is a wealth of information available on the Internet. Here are some reliable websites to get you started:

www.newzealand.com is the official site for New Zealand tourism.

www.doc.govt.nz, the Department of Conservation site, provides everything you need to know about parks and recreation across New Zealand. Independent walkers will find all the information needed to plan their trip.

www.ultimatehikes.co.nz has everything you need to know about booking the guided track walk.

www.tramper.co.nz features good information for tramping anywhere in New Zealand.

www.destination-nz.com provides excellent website listings.

www.queenstownnz.co.nz is the town’s official site.

www.queenstown-vacation.com has good information on everything relating to Queenstown and area.

This reading list focuses on the Milford Track and the Milford Sound area only and does not include broader coverage of New Zealand in general.

KIWI Footpaths Track Guide No. 1: The Milford – Gordon and Michelle Hosking and Peter and John Kamp – an excellent waterproof guide that will fit in a pocket. The spiral binding ensures it can be opened to any page and remain perfectly flat, while the two kilometre per page sectional maps provide an easy to follow visual summary of the entire track from Glade Wharf to Sandfly Point. Plus additional information on history, geology, flora and fauna, it is highly recommended. Probably best to look for this when you are in New Zealand.

Lonely Planet: New Zealand – I tend to be partial to the Lonely Planet series if you are looking for a comprehensive guidebook to help plan your trip.

Lonely Planet: Tramping in New Zealand – Jim DuFresne – somewhat dated, this guide provides good information on tramping all over New Zealand, including a section on the Milford Track.

Milford Sound: An Illustrated History of the Sound, the Track and the Road – John Hall-Jones – an excellent source for historical information, maps and photographs, many published here for the first time. Available online through Craigs Design and Print Ltd. at www.craigprint.co.nz. Highly recommended.

The Finest Walk in the World – Blanche Baughan – is still available from used book sellers. I located a copy through www.amazon.ca. Written in the flowery language typical of the early 1900s, it gives a wonderful description of the birds, the plants and the sights along the trail.

The Milford Track Navigator – an excellent waterproof fold-out includes a good map and day to day description of the route. A copy of this is supplied by Ultimate Hikes when you sign up for the guided walk.

Walking the Milford Track – Rosalind Harker – written by a former manager of the Pompolona Hut, the book provides a wealth of information on the birds and the flora along with colour photographs to help with identification. There is a detailed description of the hike as well as a chapter on the history of the famous track. Probably best to look for this when you are in New Zealand.

New Zealand kea parrot.

© FOTOSEARCH.COM