SREBRENICA SAFE AREA, JULY 6, 1995

Dutch Private First Class Marc Klaver peered into the predawn darkness. Perched in the watchtower of UN Observation Post Foxtrot, Klaver couldn’t get his bleary eyes to focus. His mind drifted. It was just after 5 a.m. One hour into a four-hour shift, Klaver and the other peacekeeper on duty—Dutch Private First Class Raviv van Renssen—were bored.

A bright flash abruptly lit up the sky to the east. A detonation rolled across the open fields. Startled, Klaver and van Renssen instinctively turned toward the light and sound. A deafening explosion shook the tower. “Shit!” Klaver shouted as the two young soldiers dove to the plywood floor. Chunks of dirt cascaded over Biljeg, the hilltop that OP Foxtrot was perched on. Klaver and van Renssen stared at each other in disbelief.

Silence hung over the hill for a few seconds. Another flash and detonation to the east. The two young soldiers, dressed in camouflage T-shirts and shorts, pressed their chests against the floor. A shell whistled overhead. A second explosion rocked the hilltop. Klaver, twenty-three, was disoriented. Van Renssen, twenty-five, a mortar specialist, realized the first explosion was the sound of a mortar firing in front of them. The whistle was the mortar passing overhead. The second explosion was the impact behind them.

He fumbled for the radio. “Ops room, this is OP Foxtrot! Over!” van Renssen shouted.

“This is ops room. Over,” a sleepy voice answered back from the operations room in the UN Bravo Company base in Srebrenica town.1

“This is Foxtrot. We had two detonations near the OP!” van Renssen shouted. “Mortar grenades! Fired over the OP from the Serb side!”

Klaver desperately pressed his long, thin frame against the floor and wondered if this was really happening. His ears rang. Sweat covered him. Observation Post Foxtrot had been nicknamed “OP Holiday,” “OP Sun Beach” and “OP Relax,” because so little happened there. Klaver and the five other peacekeepers had spent much of their time sunbathing. This was the first time Foxtrot had been shelled since their battalion arrived five months earlier.

Klaver and van Renssen scrambled down a ladder into a sandbag bunker beneath the tower. Klaver was worried. They’d heard over the radio that the Bosnian Serbs had fired six rockets over the Dutch headquarters compound in the village of Poto ari at 3:15 a.m. The day before, one piece of Serb long-range artillery had abruptly appeared on a hill a mile north of the observation post. Roughly a hundred Bosnian Serb soldiers with thin white ribbons tied to their shoulders had been seen walking east. Ribbons were the primary way soldiers in Bosnia—who were physically identical and generally wore the same uniforms—could identify which side they were on. Finally, a pickup truck towing an antiaircraft gun, which the Serbs used to fire on people not airplanes, had been seen driving north.

ari at 3:15 a.m. The day before, one piece of Serb long-range artillery had abruptly appeared on a hill a mile north of the observation post. Roughly a hundred Bosnian Serb soldiers with thin white ribbons tied to their shoulders had been seen walking east. Ribbons were the primary way soldiers in Bosnia—who were physically identical and generally wore the same uniforms—could identify which side they were on. Finally, a pickup truck towing an antiaircraft gun, which the Serbs used to fire on people not airplanes, had been seen driving north.

Klaver had reported everything to the operations room in Srebrenica town, but had been told not to worry. He thought the vague answer meant his commanders didn’t know what to make of the Serb troop movements either.

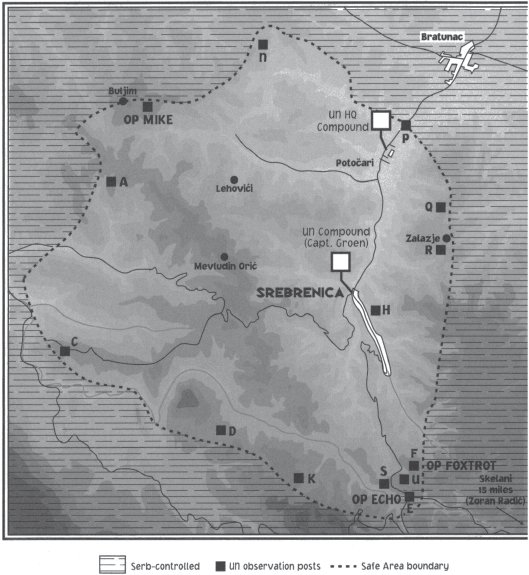

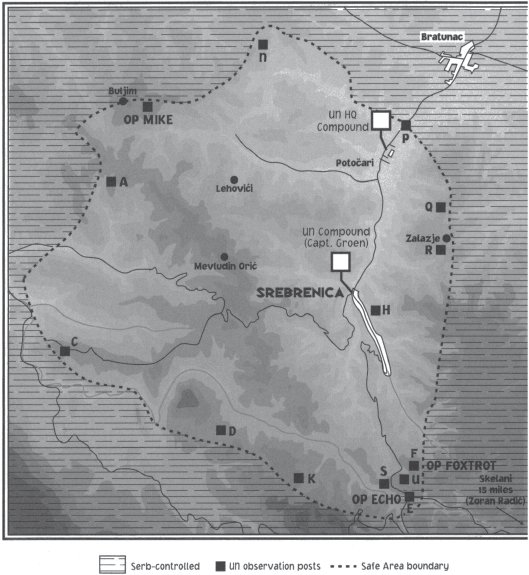

Set on the highest hill in the southeast corner of the enclave, OP Foxtrot was a microcosm of the confused UN mission in Bosnia.

On the one hand, Klaver and the Dutch were supposed to be neutral UN peacekeepers. They wore bright blue UN helmets, berets or baseball caps. Nearly every inch of the observation post’s fifty-by-thirty-yard compound of prefabricated containers, canvas tents and sandbag bunkers was UN white. OP Foxtrot could be spotted—and shelled—from miles away. As far as Klaver, van Renssen and the other Dutch were concerned, OP Foxtrot was a great white albatross, not a defensive position.

But Klaver and his fellow peacekeepers were also expected to take sides if necessary and “deter” attacks by the Bosnian Serbs. Muslim soldiers had grudgingly turned over this and a half dozen other strategic hills to the UN when Srebrenica became a safe area. Klaver could see the jagged ridges and steep hills of eastern Bosnia rising and falling for five miles in each direction from his fifteen-foot watchtower. It was unforgiving terrain. It was almost impossible for someone to sneak up to the observation post or mount a major attack on the town without being seen. But with few weapons, blue helmets and white vehicles, the Dutch were a meager fighting force. Both confused and discouraged by their contradictory mission, Klaver and Srebrenica’s Dutch peacekeepers had spent most of the last five months hoping nothing would happen.

Klaver loved being a soldier, but had felt uncomfortable as soon as he arrived in Srebrenica. A long-range rifleman, he was used to digging in and concealing himself, not painting his surroundings white. The Dutch battalion were paratroopers trained to be highly mobile. They had been taught to fire, quickly move to a new position and fire again. Firing from various locations made it difficult for the enemy to locate them or assess their strength, but in Srebrenica and all of Bosnia, UN peacekeeping doctrine was that the activities of UN soldiers should be “transparent.” Peacekeepers were to go out of their way to make it easy for all sides to see what they were doing and make themselves vulnerable.

For Klaver, the safe area was a humiliating joke. The Muslims refused to be disarmed and carried out raids into Serb territory at night. Both sides occasionally sniped at the Dutch and each other. As soon as he’d seen the rugged hills and thirty-mile front line around the enclave, Klaver had known that his 750-man battalion couldn’t defend Srebrenica with the limited weapons and equipment they had.

The Bosnian Serbs had blocked their resupply convoys for months. The Dutch had received no diesel fuel since February 18 and were using mules and tractors to supply most of their thirteen observation posts. They had run out of fresh food two months ago and had been eating only combat rations. Klaver hadn’t had a real cigarette or a beer in four weeks. The Dutch traded food sometimes for yellow tobacco leaves grown by local Muslims. They were usually without cigarette paper, sometimes rolling the tobacco in magazine paper. Graffiti in the OP, left by past and present peacekeepers, read, “Dutchbat Victim,” “Dope again” and “Come back Shitty Muslim.”

After the first half hour of shelling, it started to become predictable. Klaver and van Renssen relaxed as they sat in Foxtrot’s sandbag bunker and listened to the shells impacting outside. It was clear the Bosnian Serbs were not targeting the observation post. They were pulverizing the network of World War I-era trenches the Muslims had built behind the OP and on the small hills that flanked it. Klaver could hear Muslims intermittently firing AK-47 assault rifles and mortars at the Bosnian Serbs from their trenches. They fired at most a dozen mortar shells at the Bosnian Serbs. The peacekeepers were unimpressed, but still jittery.

Klaver and van Renssen climbed back up into the tower at around 7 a.m. Peering through his binoculars, Klaver saw that three tanks, two howitzer artillery pieces and a multiple rocket launcher had taken up position 1,600 yards east of the observation post. The shells and rockets flew by their watchtower trailing beautiful, long tails of fire. As the scorching July sun slowly rose, Klaver and van Renssen started to enjoy the spectacle. “Look at that one,” Klaver said as a rocket flew by.

The most surreal moment of the morning came during a lull in the shelling. A bus pulled up next to the Serb artillery positions. A group of military officers stepped out. Like gawking tourists, they snapped photos of the OP and left. Klaver was again surprised by the Muslim response. No snipers appeared to shoot at the Serb officers.

At around 1 p.m., a shell abruptly tore into the front wall of the OP. The watchtower felt like it was collapsing. The sandbags over Klaver’s and van Renssen’s heads shook violently. Sand poured onto their helmets. Klaver felt his heart pounding in his throat. One of the Serb tanks was directly targeting them.

Four miles to the northwest, twenty-five-year-old Mevludin Ori , a Bosnian Muslim soldier, was nervously enjoying the spectacle. Standing on top of the 2,900-foot Mount Zvijezda in the center of the safe area, Mevludin, his neighbor Azem Dautovi

, a Bosnian Muslim soldier, was nervously enjoying the spectacle. Standing on top of the 2,900-foot Mount Zvijezda in the center of the safe area, Mevludin, his neighbor Azem Dautovi and several women were watching Serb shells careen into the safe area. Mevludin had tried to walk into Srebrenica town that morning but gave up when he saw the extent of the shelling. Mevludin was confident that UN commanders in Sarajevo would soon retaliate against the Serbs.

and several women were watching Serb shells careen into the safe area. Mevludin had tried to walk into Srebrenica town that morning but gave up when he saw the extent of the shelling. Mevludin was confident that UN commanders in Sarajevo would soon retaliate against the Serbs.

A multiple rocket launcher in the Bosnian Serb-held town of Bratunac just north of Srebrenica was firing into the enclave. Mevludin was impressed by the thunderous sound of the rockets launching, buzzing through the air and then detonating. It was the first time the Serbs had fired them into Srebrenica since it was designated a safe area.

Mevludin had quickly decided that Srebrenica’s Dutch peacekeepers were little more than greedy cowards. They had come here to make money, he thought, not to protect the safe area. While the Dutch lived like kings, hunger still haunted the overcrowded enclave’s people. The Bosnian Serbs blocked UN food convoys at will. Each day, local Muslims would venture to OP Mike, the nearest UN post, and wait patiently for the Dutch to throw away their garbage. The refuse was then painstakingly searched for scraps of food. He expected the Dutch to run at the first sign of a serious attack.

But the Dutch weren’t the biggest reason Mevludin Ori felt uneasy that morning, Naser was.

felt uneasy that morning, Naser was.

Naser Ori was Srebrenica’s charismatic twenty-nine-year-old commander and Mevludin Ori

was Srebrenica’s charismatic twenty-nine-year-old commander and Mevludin Ori ’s distant cousin. He had left the enclave two months ago. Mevludin had heard that Naser and fifteen of Srebrenica’s best officers slipped out of town under cover of darkness and trekked ten miles south to Žepa, a second Muslim UN-declared safe area. From there, they had been ferried by helicopter to Muslim-held central Bosnia in April. The fifteen officers were supposed to be attending a short-term training course. But only two of the fifteen, the deputy commander and one brigade commander, had returned.

’s distant cousin. He had left the enclave two months ago. Mevludin had heard that Naser and fifteen of Srebrenica’s best officers slipped out of town under cover of darkness and trekked ten miles south to Žepa, a second Muslim UN-declared safe area. From there, they had been ferried by helicopter to Muslim-held central Bosnia in April. The fifteen officers were supposed to be attending a short-term training course. But only two of the fifteen, the deputy commander and one brigade commander, had returned.

With Naser leading them, with his trademark .50 caliber machine gun, Srebrenica’s defenders felt invulnerable. The bearded, six-foot-one-inch bodybuilder had jet-black hair and an enormous chest and powerful arms. A tough-talking former local policeman and prewar bodyguard for Serbian President Slobodan Miloševi , he had spurred the Muslims on to spectacular victories in 1992. He was adored by his men and feared by his adversaries. Ambitious and ruthless, Naser had turned Srebrenica into his fiefdom. No one knew when he was coming back, but his absence hung over Mevludin Ori

, he had spurred the Muslims on to spectacular victories in 1992. He was adored by his men and feared by his adversaries. Ambitious and ruthless, Naser had turned Srebrenica into his fiefdom. No one knew when he was coming back, but his absence hung over Mevludin Ori and Srebrenica’s soldiers.

and Srebrenica’s soldiers.

The UN’s arrival in April 1993 had been a military disaster for Srebrenica’s defenders. The Muslims2 had formally disbanded their units and turned over the two tanks and the handful of artillery pieces they had captured from the Serbs—in compliance with the demilitarization agreement that was part of being a safe area. Dutch observation posts now sat on top of a half dozen of the most strategic hills along the enclave’s front line. Every six months a new battalion of peacekeepers arrived. During the rotation of the UN troops, the Bosnian Serbs crept forward and took crucial high ground.

The worst case stared Mevludin in the face every day. In 1993—armed with automatic rifles and homemade guns that consisted of iron pipes filled with nails and gunpowder—the Muslims had fought desperately to hold half of Buljim, a 2,300-foot peak that loomed over the northwest corner of the enclave. Men Mevludin had known died holding that ground. The Muslims allowed the UN to set up an observation post on their half of the peak. In January 1994, the observation post was empty for several days while UN troops rotated in and out of the enclave. In the middle of the night, the Bosnian Serbs took the observation post and the hill. The Dutch complained, but as with everything else, refused to use force to get it back.

Six feet two, rail thin and wiry, Mevludin had a boyish face dotted with freckles and barely any facial hair. Constantly joking and teasing, he looked more like a teenager than a father of two. He, his wife and two children lived with his father. He made a meager living by brewing and selling šljivovica, or plum brandy, which enabled him to buy the precious salt, sugar and coffee his family needed. Alcohol prices fluctuated wildly in the enclave from three to fifteen dollars for a sixteen-ounce bottle, depending on the supply. There was little to do in the besieged town, so the demand was constant.

Mevludin had never expected the war. He had loved Yugoslavia and was sickened by its breakup. Once Croatia and Slovenia declared independence in June 1991, he knew Bosnia had to also. What was left of Yugoslavia would be totally dominated by Serbia, which had three times as many people as Bosnia. He was sure the Serbs would discriminate against Bosnia’s Muslims. He was willing to live in Yugoslavia, not “Serboslavia,” as Muslims jokingly called what was left of Tito’s “land of the South Slavs.”

Mevludin had grown up in Lehovi i, a tiny village ten miles northwest of Srebrenica inhabited by only ten Muslim families. He’d gone to a vocational high school in Slovenia to become a mining technician. Homesick and having a difficult time understanding Slovenian, a language related to, but different from the Serbo-Croatian spoken in the rest of Yugoslavia, he dropped out of school at fifteen. In 1985, Mevludin took a job in a sugar factory in Belgrade, the capital of Serbia. For the next three years, the small-town boy had the time of his life getting drunk and chasing women in the cafés and clubs of Kalemegdan—Belgrade’s old town.

i, a tiny village ten miles northwest of Srebrenica inhabited by only ten Muslim families. He’d gone to a vocational high school in Slovenia to become a mining technician. Homesick and having a difficult time understanding Slovenian, a language related to, but different from the Serbo-Croatian spoken in the rest of Yugoslavia, he dropped out of school at fifteen. In 1985, Mevludin took a job in a sugar factory in Belgrade, the capital of Serbia. For the next three years, the small-town boy had the time of his life getting drunk and chasing women in the cafés and clubs of Kalemegdan—Belgrade’s old town.

He returned to Lehovi i in 1990, and met his future wife, Hadzira when visiting his sister in a nearby village. Mevludin was only twenty and Hadzira only fifteen but the two married that year. Five years later, Mevludin had two daughters and spent most of his time with his twenty-four-year-old cousin and best friend, Haris. They passed the long, boring days in the enclave hunting. Their biggest treat was eating meat, or watching blurry pirated copies of Jean-Claude Van Damme movies. A makeshift waterwheel his father had built in a nearby stream barely generated enough power for a TV and VCR together. Somehow, the enclave’s 40,000 people had lived without electricity or running water for three years.

i in 1990, and met his future wife, Hadzira when visiting his sister in a nearby village. Mevludin was only twenty and Hadzira only fifteen but the two married that year. Five years later, Mevludin had two daughters and spent most of his time with his twenty-four-year-old cousin and best friend, Haris. They passed the long, boring days in the enclave hunting. Their biggest treat was eating meat, or watching blurry pirated copies of Jean-Claude Van Damme movies. A makeshift waterwheel his father had built in a nearby stream barely generated enough power for a TV and VCR together. Somehow, the enclave’s 40,000 people had lived without electricity or running water for three years.

A month earlier, Makso Zeki —a Serb Mevludin had feuded with years ago—had started asking around about Mevludin. In a practice that was common throughout Bosnia, Serbs and Muslims regularly talked to each other from opposing trenches. Makso had vowed that he was personally going to burn Mevludin’s home to the ground. Their quarrel was over some trees Mevludin had asked Makso to haul to the lumber mill in his truck before the war. Mevludin accused Makso of cheating him. The sudden threat from Makso struck him as odd.

—a Serb Mevludin had feuded with years ago—had started asking around about Mevludin. In a practice that was common throughout Bosnia, Serbs and Muslims regularly talked to each other from opposing trenches. Makso had vowed that he was personally going to burn Mevludin’s home to the ground. Their quarrel was over some trees Mevludin had asked Makso to haul to the lumber mill in his truck before the war. Mevludin accused Makso of cheating him. The sudden threat from Makso struck him as odd.

Relations with other Serbs were also strained. Mevludin and some men in his unit used to trade the food they had grown for salt, sugar and cigarette paper. But as the weather warmed, the Serbs talked less and shot more. Most unsettling of all, the Serbs knew Naser was gone.

“Where is your Naser now?” Serbs had shouted from their trenches, according to other Muslim soldiers. Mevludin Ori didn’t have an answer.

didn’t have an answer.

Klaver anxiously watched the three Serb tanks on the hill 1,500 yards away. The two T-54 battle tanks—modern by Bosnia standards—appeared not to be firing at the OP. That job was left to what looked like a World War II-era Soviet-made T-34, which was so primitive that it had to come to a complete stop before it could fire a shell. But Klaver knew a direct hit could kill him just the same.

The T-34 emerged from behind some trees. A puff of thick gray smoke burst from the tank’s barrel. The lookouts dove to the floor of the watchtower, fearing they might be incinerated.

Klaver, van Renssen and Jeroen Dekkers, another lookout, quickly learned the acoustics of war. Bullets and shells travel faster than sound. Hearing a shell when you are under fire is a good thing; it means the shells have already passed by or over you. You never hear the shell that kills you. The exceptions are slower-moving mortars and rockets. They can be heard shrieking through the air moments before impact.

As the tank fired, Sergeant Frans van Rossum, OP Foxtrot’s twenty-seven-year-old commander, stood under the tower in direct radio contact with Captain Jelte Groen, the Dutch commander of the southern half of the enclave. Van Rossum demanded that he and his men receive Close Air Support from NATO planes or be allowed to withdraw.

“Do you see the tank? Do you see the tank?” van Rossum shouted to the lookouts in a panic. “Is the turret turning toward us?”

The T-34 nosed out from the trees every thirty to forty-five minutes and fired two or three rounds at the observation post. At 3 p.m., they figured out that the tank was firing every time they appeared in the tower. The Serbs could see their bright blue UN helmets.

Van Rossum ordered all seven of the OP’s men to the bunker. The peacekeepers cowered inside the claustrophobic, ten-by-ten-foot room surrounded by sandbags. They were waiting to die. If the shells didn’t kill them, the collapsing sandbag walls would smother them. There were no windows, just tiny peepholes the Dutch could barely see out of. Blind to what was happening around them, they listened helplessly as shells screeched through the air and shook the earth beneath them.

At 4 p.m., four hours after the first shell hit the OP, Captain Groen told them that NATO Close Air Support had been requested. The Dutch had been told throughout their training that when a UN post was directly targeted, peacekeepers had the right to fire back, or to call in NATO Close Air Support. If the Serbs ever threatened to take the enclave, NATO air strikes—which would involve several Serb targets being hit at once—could be requested.

Relief washed over the group. Soldiers who served in the last Dutch battalion in Srebrenica had told them how they had called in NATO planes when one of their patrols was fired on by the Serbs. Twenty minutes later, NATO jets roared over the Serb positions and dropped flares. The firing stopped immediately.

But as the torturous shelling continued Thursday afternoon, no NATO planes appeared. Captain Groen said they had been requested, but it was up to UN commanders in Sarajevo to approve the attack. The men in Foxtrot asked if they could withdraw. Captain Groen ordered them to stay.

Frustration and fear mounted. There was little enthusiasm among the Dutch peacekeepers to fire at the Serbs themselves. They had come to Bosnia to be peacekeepers, not to die in someone else’s war.

Klaver had wanted to go to Bosnia. He thought he could help people as a peacekeeper. The son of a retired construction company manager and a housewife, Klaver was tall—six feet five inches—and handsome, with a broad face, short brown hair and clear blue eyes. Klaver’s size and looks weren’t reflected in his personality. Gentle and soft-spoken, he was modest and acted with deference toward those around him.

What he missed the most in Bosnia was his brother Tonny. At twenty-three, Klaver was by far the youngest of five boys in the family. His oldest brother was forty-four. Tonny was only nine years older than Klaver and the closest to him in age. The two had more or less grown up together. The young peacekeeper respected his older brother for his courage and loved his sense of humor. Tonny had cystic fibrosis but lived on his own and enjoyed as normal a life as possible. The Serbs had cut off most mail shipments to the enclave and Klaver was allowed only one five-minute phone call home a month. Tonny had said nothing in his letters, and his parents had said nothing on the phone. But for the last month Klaver had sensed that something was wrong. He was afraid Tonny wouldn’t be there when he finally went home.

Klaver had grown up in Boekelo, a town of 5,000 in rural eastern Holland that was ten miles from the German border. He had studied business for three years and dropped out of college to join the army.

The most powerful weapon at OP Foxtrot, a highly accurate, American-made TOW antitank missile, was already useless. It was sitting on the roof. Thinking of themselves as neutral UN observers, the Dutch peacekeepers who first arrived in Srebrenica in January 1994 had mounted the missile on the roof of Foxtrot’s watchtower. From there, its telescopic night vision sight could see the farthest. The sight enabled them to track Serb troop movements or Muslim raiding parties. Klaver and the other Dutch had thought nothing of the strange position of the TOW when they arrived. To operate it, one of them would have to stand in the open on the roof, load the missile, aim it, fire and guide it as the missile flew, and be vulnerable to sniper fire for at least a minute and a half.

There was another problem. Foxtrot had seven TOW missiles, but only one launcher. The TOW launchers were designed to be used in pairs because they took so long to reload. Even if they could take out a T-34 with a TOW, the two T-54 tanks would destroy the OP before they could reload.

The Serbs had allowed only six TOW launchers into the enclave when the Dutch first entered in 1994. The Dutch commanders at the time decided to place the launchers in six different locations around the enclave to maximize their observation capabilities. In essence, the launchers and their night vision sights were deployed simply as expensive binoculars, not as weapons.

The OP also had two Dragon antitank missiles. Their range was only 500 yards. They had 81 mm mortars, but against tanks a direct hit was required; basically, they were effective only against infantry. Their .50 caliber and Uzi machine guns as well as their rifles were useless against tanks and artillery. Finally, the TOW hadn’t been fired since 1994 and much of the other ammunition was old. The Dutch were worried their weapons might not fire.

In the end, they decided the worst thing they could do was provoke the better-armed Serbs. They were following the logic used by many UN commanders in Bosnia: don’t put a red cloth in front of a bull. The seven decided that if the Serbs came into the OP firing and it was clear they were going to die, the Dutch would fire back with everything they had. Otherwise, they would wait.

By 5 p.m., NATO planes had still not appeared. Explosions continued to rock the hilltop every fifteen to thirty minutes. The Dutch wanted to believe that the Serbs were trying to flush them out of the OP without killing them. All the shells landed at the edges of the compound, or in the barbed wire around it. The seven knew a single random shell could destroy the bunker. The Dutch cowered and waited.

Finally at 7 p.m. Thursday, the shelling stopped. Klaver estimated that more than 200 shells had landed. The OP had been hit approximately a half dozen times. It had been three hours since Close Air Support was requested. NATO planes were nowhere to be seen.

Twenty miles south of Srebrenica in the Bosnian Serb-held town of Skelani, Bosnian Serb police officer Zoran Radi went about his duties on July 6 as if it were any other day. The thirty-year-old was unaware of the attack unleashed that morning that would change the course of the war and his life.3

went about his duties on July 6 as if it were any other day. The thirty-year-old was unaware of the attack unleashed that morning that would change the course of the war and his life.3

A Bosnian Serb who grew up in Srebrenica, Radi longed for the Serbs to retake his hometown. Radi

longed for the Serbs to retake his hometown. Radi had been stunned when fighting broke out in April 1992. Like so many other people in Bosnia, he had joked with his Muslim and Croat friends as Yugoslavia disintegrated and believed that war would never come. But a book he read during 1992 in a Serb trench around Sarajevo had answered many questions for him.

had been stunned when fighting broke out in April 1992. Like so many other people in Bosnia, he had joked with his Muslim and Croat friends as Yugoslavia disintegrated and believed that war would never come. But a book he read during 1992 in a Serb trench around Sarajevo had answered many questions for him.

Entitled Bloody Hands of Islam, it described atrocities carried out around Srebrenica by Muslim and Croat Fascists allied with Hitler during World War II.4 The book had been banned by Tito’s government. Forty Serbs had been executed in Zalazje, a village just outside Srebrenica. Radi could see that history was repeating itself. Roughly fifty years later, on July 12, 1992—the Serb Orthodox holiday of St. Peter’s Day—Naser Ori

could see that history was repeating itself. Roughly fifty years later, on July 12, 1992—the Serb Orthodox holiday of St. Peter’s Day—Naser Ori ’s men killed 120 people in the same town. As time passed Radi

’s men killed 120 people in the same town. As time passed Radi decided the war was a good thing. The Serbs needed to live separately from the Muslims for their own protection.

decided the war was a good thing. The Serbs needed to live separately from the Muslims for their own protection.

Before the war, Radi had always felt that he and his family were discriminated against by the Muslim majority in Srebrenica. His father worked as a miner for twenty-five years, but never received a company-owned apartment. Muslims who worked for only five to ten years as miners got them instead. Radi

had always felt that he and his family were discriminated against by the Muslim majority in Srebrenica. His father worked as a miner for twenty-five years, but never received a company-owned apartment. Muslims who worked for only five to ten years as miners got them instead. Radi had been unable to find work in town after he graduated from high school, he felt, because he was a Serb.5

had been unable to find work in town after he graduated from high school, he felt, because he was a Serb.5

Radi opposed Bosnia’s declaration of independence. He was sure Serbs would be discriminated against even more if Bosnia became a separate country. Muslims would be the largest group; he didn’t trust the Muslim politicians in Sarajevo to rule over him. Serbs had been forced to convert to Islam during the Turks’ 500-year occupation of Bosnia between the fourteenth and nineteenth centuries. Serbs had also been forced to convert to Catholicism at gunpoint by Croat Fascists in World War II. Echoing the warnings of Serb nationalist politicians, he feared that the same thing would happen again in an independent Bosnia.6

opposed Bosnia’s declaration of independence. He was sure Serbs would be discriminated against even more if Bosnia became a separate country. Muslims would be the largest group; he didn’t trust the Muslim politicians in Sarajevo to rule over him. Serbs had been forced to convert to Islam during the Turks’ 500-year occupation of Bosnia between the fourteenth and nineteenth centuries. Serbs had also been forced to convert to Catholicism at gunpoint by Croat Fascists in World War II. Echoing the warnings of Serb nationalist politicians, he feared that the same thing would happen again in an independent Bosnia.6

For Radi it was simple. If the Muslims had the right to secede from Yugoslavia, ethnic Serbs should have the right to secede from Bosnia and unite with Serbia. He didn’t understand why the world had created such a double standard and opposed a “Greater Serbia.” Tito had divided ethnic Serbs among Serbia, Bosnia, and Croatia, he thought, in an effort to weaken Serb power. Radi

it was simple. If the Muslims had the right to secede from Yugoslavia, ethnic Serbs should have the right to secede from Bosnia and unite with Serbia. He didn’t understand why the world had created such a double standard and opposed a “Greater Serbia.” Tito had divided ethnic Serbs among Serbia, Bosnia, and Croatia, he thought, in an effort to weaken Serb power. Radi thought the Bosnian Serbs, who made up only 30 percent of Bosnia’s population but had won control of 70 percent of its territory, had clearly won the war. Somehow the Muslims had convinced the Americans and Europeans that they were the victims.

thought the Bosnian Serbs, who made up only 30 percent of Bosnia’s population but had won control of 70 percent of its territory, had clearly won the war. Somehow the Muslims had convinced the Americans and Europeans that they were the victims.

Srebrenica’s Muslims and Naser Ori had played the United Nations beautifully in 1993. When the Serbs were on the verge of taking the town, they had tricked the West into saving them. The safe area was a joke. For two years, the UN had fed the Muslims, sold them weapons and done nothing as Naser Ori

had played the United Nations beautifully in 1993. When the Serbs were on the verge of taking the town, they had tricked the West into saving them. The safe area was a joke. For two years, the UN had fed the Muslims, sold them weapons and done nothing as Naser Ori launched raids from a town that was supposed to be “demilitarized.”7 Serb villagers within thirty miles of Srebrenica lived in constant fear, waiting to hear the voices in the night and then smell smoke. Dozens of civilians had been burned alive in their homes by Ori

launched raids from a town that was supposed to be “demilitarized.”7 Serb villagers within thirty miles of Srebrenica lived in constant fear, waiting to hear the voices in the night and then smell smoke. Dozens of civilians had been burned alive in their homes by Ori ’s men. They had burned Radi

’s men. They had burned Radi ’s village, Obadi, to the ground in June 1992.

’s village, Obadi, to the ground in June 1992.

Radi remembered Naser Ori

remembered Naser Ori from before the war. Naser was athletic, but he hadn’t caused much trouble. Radi

from before the war. Naser was athletic, but he hadn’t caused much trouble. Radi ’s cousin had gone to school with him. Now Naser was the most hated Muslim commander in all of Bosnia. Bratunac had the second-highest casualty rate of any Serb-held community in Bosnia. Roughly 3,000 Serb soldiers and civilians had been killed around Srebrenica. Ori

’s cousin had gone to school with him. Now Naser was the most hated Muslim commander in all of Bosnia. Bratunac had the second-highest casualty rate of any Serb-held community in Bosnia. Roughly 3,000 Serb soldiers and civilians had been killed around Srebrenica. Ori ’s men killed every prisoner they took so there would be no witnesses, it was rumored. Serb bodies had also been reportedly found with heads and ears cut off. Prisoners were allegedly skinned alive.8

’s men killed every prisoner they took so there would be no witnesses, it was rumored. Serb bodies had also been reportedly found with heads and ears cut off. Prisoners were allegedly skinned alive.8

At five feet ten inches tall with a medium build, Radi was far from intimidating. His thick brown hair, large brown eyes and easy smile combined to give his round face a soft, nonthreatening look. He had an easygoing manner that made people around him relax. Like Bosnian Muslim soldier Mevludin Ori

was far from intimidating. His thick brown hair, large brown eyes and easy smile combined to give his round face a soft, nonthreatening look. He had an easygoing manner that made people around him relax. Like Bosnian Muslim soldier Mevludin Ori , Radi

, Radi had left Srebrenica for the big city as a teenager. Unable to find a job in Srebrenica, he studied business at a university in Sarajevo and graduated with a two-year degree in 1986. Bored with college at twenty-one, Radi

had left Srebrenica for the big city as a teenager. Unable to find a job in Srebrenica, he studied business at a university in Sarajevo and graduated with a two-year degree in 1986. Bored with college at twenty-one, Radi started working as a cook in hotels on the scenic coast of Croatia. The next five years were the happiest of his life. He would probably still be on the coast of Croatia if the war hadn’t broken out.

started working as a cook in hotels on the scenic coast of Croatia. The next five years were the happiest of his life. He would probably still be on the coast of Croatia if the war hadn’t broken out.

While he believed in the Serb cause, Radi did not believe in killing innocent people and had prided himself on treating people well throughout the war. He had spent the first two years of the war working as a guard in a combined civilian and military prison outside Sarajevo and he disliked the brutality of it. A handful of the thirty guards relished beating the Muslim prisoners of war, but Radi

did not believe in killing innocent people and had prided himself on treating people well throughout the war. He had spent the first two years of the war working as a guard in a combined civilian and military prison outside Sarajevo and he disliked the brutality of it. A handful of the thirty guards relished beating the Muslim prisoners of war, but Radi had never participated.9 When the fighting flared around Sarajevo, his police unit was called up to the front line. Radi

had never participated.9 When the fighting flared around Sarajevo, his police unit was called up to the front line. Radi had spent long hours in the trenches surrounding a city he remembered fondly.

had spent long hours in the trenches surrounding a city he remembered fondly.

The fighting had been bitter at times. The Muslim and Serb trenches were only 200 yards apart. But the chatter had also been fairly constant throughout the war. Radi had known the price of cigarettes, bread and rakija—another kind of homebrewed brandy—in most markets in Sarajevo. If asked, one side would tell the other what time it was. One day, they serenaded each other, the Muslims singing traditional Serb songs and the Serbs singing old Muslim songs. The Muslims even invited Radi

had known the price of cigarettes, bread and rakija—another kind of homebrewed brandy—in most markets in Sarajevo. If asked, one side would tell the other what time it was. One day, they serenaded each other, the Muslims singing traditional Serb songs and the Serbs singing old Muslim songs. The Muslims even invited Radi over for coffee several times, but he was never crazy enough to accept.

over for coffee several times, but he was never crazy enough to accept.

In March 1995, Radi had moved from Sarajevo to Skelani to be closer to his parents and two brothers living in Bratunac. He never thought he’d set foot in his hometown again, but if Srebrenica did ever fall, Radi

had moved from Sarajevo to Skelani to be closer to his parents and two brothers living in Bratunac. He never thought he’d set foot in his hometown again, but if Srebrenica did ever fall, Radi was sure of one thing: the Serbs would treat civilians and prisoners far more humanely than Naser Ori

was sure of one thing: the Serbs would treat civilians and prisoners far more humanely than Naser Ori did.

did.