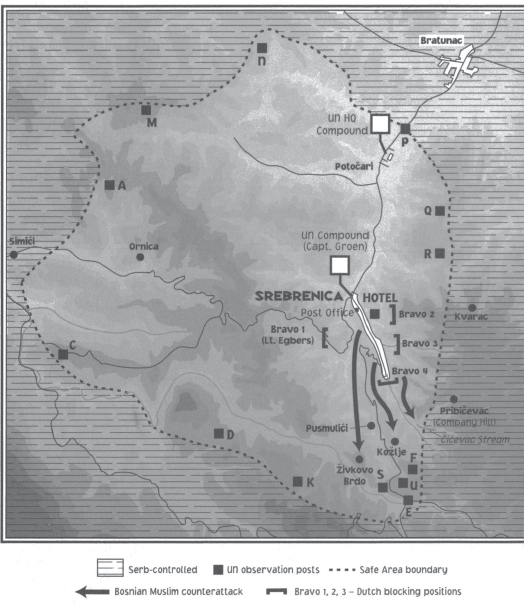

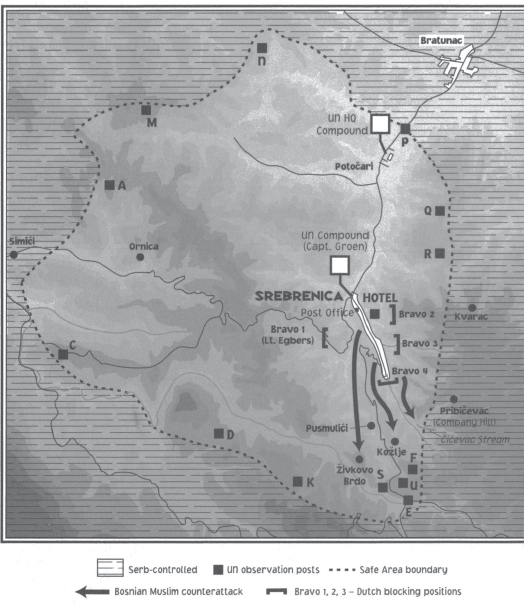

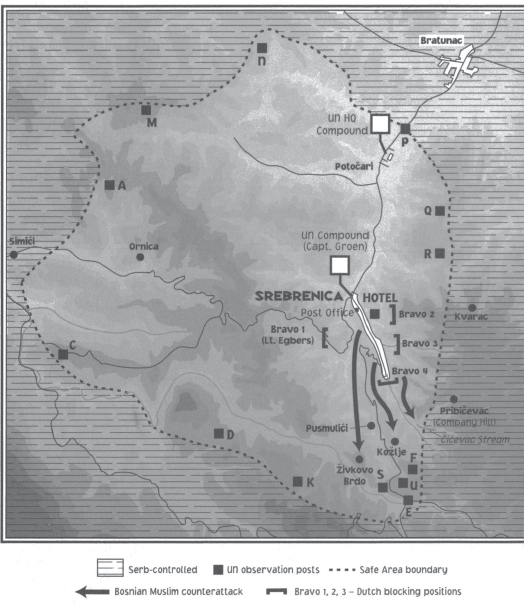

BOSNIAN MUSLIM COUNTERATTACK, JULY 10, 1995

Captain Mido Salihovi and his men had somehow reached the spot without being seen. A Serb T-54 tank sat in the center of the road 100 yards away. A car and some kind of truck were parked next to it. About thirty Serb soldiers slept peacefully in the open air. It was 6:50 a.m.

and his men had somehow reached the spot without being seen. A Serb T-54 tank sat in the center of the road 100 yards away. A car and some kind of truck were parked next to it. About thirty Serb soldiers slept peacefully in the open air. It was 6:50 a.m.

Salihovi , twenty of his men and two unarmed volunteers had crept through the woods that morning from Srebrenica town to Kožlje, a hill half a mile north of OP Foxtrot. The Serb sentries were unaware of the Muslims lurking in the trees to the west. Salihovi

, twenty of his men and two unarmed volunteers had crept through the woods that morning from Srebrenica town to Kožlje, a hill half a mile north of OP Foxtrot. The Serb sentries were unaware of the Muslims lurking in the trees to the west. Salihovi , a stocky twenty-six-year-old, moved quickly. Deputy commander of Naser Ori

, a stocky twenty-six-year-old, moved quickly. Deputy commander of Naser Ori ’s elite maneuver unit, he had done this many times before.

’s elite maneuver unit, he had done this many times before.

Salihovi was still angry that they had not been able to hold the Serbs at Bibi

was still angry that they had not been able to hold the Serbs at Bibi i the day before. Using hand signals, he positioned his men. The soldier next to him aimed a rocket-propelled grenade at one of the tank’s tracks. If they blew it off, the Muslims could capture a precious tank and use it to block the road and fire on the Serbs. Salihovi

i the day before. Using hand signals, he positioned his men. The soldier next to him aimed a rocket-propelled grenade at one of the tank’s tracks. If they blew it off, the Muslims could capture a precious tank and use it to block the road and fire on the Serbs. Salihovi nodded to the soldier.

nodded to the soldier.

As the grenade launched, the sentry spun his head toward the flash in the trees. Trailing smoke, the grenade plowed into the rear of the tank. Red sparks showered the ground. Salihovi and his men opened fire with Kalashnikov assault rifles. Some Serbs went down immediately. Terrified and disoriented, the others sprinted for the woods in the opposite direction.

and his men opened fire with Kalashnikov assault rifles. Some Serbs went down immediately. Terrified and disoriented, the others sprinted for the woods in the opposite direction.

The tank’s engine started abruptly. The driver slammed it into reverse and began speeding down the road backward. The Muslims fired, but the bullets pinged off the tank’s armor. Salihovi was surprised by how fast it was backing up. One of the two unarmed volunteers reached for another RPG from his knapsack. It was empty. The grenades had fallen out of the knapsack somewhere in the woods.

was surprised by how fast it was backing up. One of the two unarmed volunteers reached for another RPG from his knapsack. It was empty. The grenades had fallen out of the knapsack somewhere in the woods.

The tank, whose track had been damaged, finally jerked to a halt near a bend 300 yards away. Salihovi and his men peppered the tank with bullets, hoping the Serbs would abandon it. The tank’s hatch stayed closed. Then they heard a second tank engine. Another T-54 was approaching slowly from the south. The undamaged tank moved up behind the damaged vehicle. Figures were seen running between the tanks. Salihovi

and his men peppered the tank with bullets, hoping the Serbs would abandon it. The tank’s hatch stayed closed. Then they heard a second tank engine. Another T-54 was approaching slowly from the south. The undamaged tank moved up behind the damaged vehicle. Figures were seen running between the tanks. Salihovi and his men fired but there was little they could do without another RPG. The T-54 began backing up. The damaged tank moved with it. The Serbs were towing it away. The roar of the tanks slowly faded in the distance.

and his men fired but there was little they could do without another RPG. The T-54 began backing up. The damaged tank moved with it. The Serbs were towing it away. The roar of the tanks slowly faded in the distance.

It was all over in fifteen minutes. The Serbs had retreated. Salihovi was astonished. While the Dutch did nothing, the Bosnians had pushed the Serbs back. To his right, a second group of thirty Muslims commanded by Veiz Šbabi

was astonished. While the Dutch did nothing, the Bosnians had pushed the Serbs back. To his right, a second group of thirty Muslims commanded by Veiz Šbabi was moving westerly through the woods to retake a hill known as Živkovo Brdo. To his left, Ibro Dudi

was moving westerly through the woods to retake a hill known as Živkovo Brdo. To his left, Ibro Dudi and another thirty men had moved into position along a stream called

and another thirty men had moved into position along a stream called  i

i evac. The Muslims’ strategy was simple. They too were ceding the southeast corner of the enclave and control of the strategic road there to the Serbs.

evac. The Muslims’ strategy was simple. They too were ceding the southeast corner of the enclave and control of the strategic road there to the Serbs.

The encampment they had attacked appeared to be the northernmost position the Serbs had taken. Almost a mile and a half of the territory the Serbs had gained the day before was left unprotected. Either the Serbs had withdrawn because they feared being surrounded in a Muslim counterattack or they decided to comply with the UN ultimatum.

Salihovi sent a messenger to town to ask for 200 reinforcements. He wanted to retake the high ground around OP Foxtrot. As he and his men approached the Serb encampment, they noticed a car and some kind of truck that looked like a field kitchen. Rifles, grenades and other equipment lay scattered around the site. Four dead Serbs lay in contorted heaps. The Muslims searched them for valuables.1

sent a messenger to town to ask for 200 reinforcements. He wanted to retake the high ground around OP Foxtrot. As he and his men approached the Serb encampment, they noticed a car and some kind of truck that looked like a field kitchen. Rifles, grenades and other equipment lay scattered around the site. Four dead Serbs lay in contorted heaps. The Muslims searched them for valuables.1

Then they gathered the Serbs’ weapons and ammunition. One volunteer beamed as he was given a Serb assault rifle. Salihovi smiled. It had been a spectacular morning.

smiled. It had been a spectacular morning.

While Salihovi collected his spoils, Lieutenant Egbers and his men were greeted by the roar of an armored personnel carrier. After a second night on the bluff, they were being reinforced. While the Muslims did nothing, Egbers thought, the Dutch were trying to stop the Serbs. Bravo One was now the western tip of the Dutch blocking position, which consisted of sixty Dutch peacekeepers and six APCs stationed on the three main roads leading into town. Captain Peter Hageman was commander of the entire blocking position.

collected his spoils, Lieutenant Egbers and his men were greeted by the roar of an armored personnel carrier. After a second night on the bluff, they were being reinforced. While the Muslims did nothing, Egbers thought, the Dutch were trying to stop the Serbs. Bravo One was now the western tip of the Dutch blocking position, which consisted of sixty Dutch peacekeepers and six APCs stationed on the three main roads leading into town. Captain Peter Hageman was commander of the entire blocking position.

Because of the steep hills and his lack of manpower and equipment, Captain Groen placed APCs and peacekeepers at the four possible entrances to Srebrenica. Egbers’ position on a bluff to the west of town, known as Bravo One, and one group near OP Hotel, which sat on a hillside to the east, referred to as Bravo Two, also had a clear view of the southern approach. Two other APCs, known as Bravo Three, were to stake out the road that led to the Serb lines to the east, while the two APCs in Bravo Four were to take a position near the castle ruins on the hill to the southeast.

Four Forward Air Controllers were placed at Bravo One and Bravo Two. Equipped with secure satellite telephones to contact Sarajevo, radios to communicate with NATO attack jets and lasers to “illuminate” targets for laser-guided bombs, the FACs were the most important weapons in the blocking position. The success of any air attack would depend largely on them.

To support the blocking position, an 81 mm mortar was set up in the center of the Dutch compound in Srebrenica.2 Weaponry continued to be a problem. Each APC had highly accurate Dragon antitank missiles, but they had a range of only 500 yards. By contrast, a Serb T-54 tank had a range of at least 1,500 yards.

In his briefing to peacekeepers the night before, Captain Groen had made one thing clear. Firing on the Serbs was to be used only as a last resort. He believed that the most valuable weapon the Dutch had—and their best tool for protecting the town’s civilians—was their role as impartial observers. Fighting the Serbs was hopeless; it would only make the situation worse for the Dutch and the civilians. Protecting civilians and his own soldiers remained Groen’s top priority.

By 7 a.m., three of the four blocking positions were in place. But Captain Hageman found the road leading to the hilltop castle where Bravo Four was to be established too narrow for his two APCs. After consulting with Groen, Hageman sent his APCs up the winding road leading to the ridge south of Srebrenica. At 7:15 a.m., an explosion rocked Hageman’s APC. The driver swerved, went off the road and barely stopped in time. The APC dangled over the side of the hill. Hageman thought it was a hand grenade thrown by a Muslim soldier that caused the explosion. The Dutch squeezed into their one remaining APC and headed back to the UN base.

amila Omanovi

amila Omanovi watched the Dutch from her balcony. She knew where the shell had come from. It was fired by the Serb tank in Pribi

watched the Dutch from her balcony. She knew where the shell had come from. It was fired by the Serb tank in Pribi evac that had been shelling the town for days. She couldn’t understand why NATO planes had not destroyed the tank yet.

evac that had been shelling the town for days. She couldn’t understand why NATO planes had not destroyed the tank yet.

She and her husband had walked up the stream running through the center of town and sneaked into their house that morning. They hoped to gather diapers for their grandson and feed their precious cow and chickens. They had fled to her daughter’s apartment in town the night before in a panic. A neighbor mistakenly told them that the Serbs were advancing toward the southern end of the town.

She peered anxiously at the forest and hillsides for signs of Serbs, and tried to figure out how to get her grandson’s diapers off the clothesline without exposing herself to sniper fire. Her husband cut each end of the clothesline and the diapers fell into the garden below.  amila then ran downstairs and reeled the clothesline into the house. Still convinced the UN would stop the Serbs, Omanovi

amila then ran downstairs and reeled the clothesline into the house. Still convinced the UN would stop the Serbs, Omanovi expected to be back home in a day or two.

expected to be back home in a day or two.

But all morning Serb artillery and mortars pounded the town in the most intense bombardment since the attack began. The roar of artillery fire and thunderous detonations echoed off the hills. Dozens of high explosives careened into houses, streets and apartment buildings. The town itself was deserted. Civilians huddled in basements and the stairwells of apartment buildings, desperate for cover.

At 8:30 a.m., a guard in the Dutch compound reported that a fire had broken out in one of Srebrenica’s buildings. Captain Groen radioed the report to his commanders in Poto ari. The Serbs were shelling the town. The Dutch weren’t sure if the Serbs had withdrawn and abided by the ultimatum.

ari. The Serbs were shelling the town. The Dutch weren’t sure if the Serbs had withdrawn and abided by the ultimatum.

The night before, Sarajevo had requested a list of the exact positions of all known Bosnian Serb artillery and tanks around the enclave. The Dutch had faxed back fifteen locations. Colonel Brantz, the UN commander in Sector Northeast, had been told that forty planes would be in the air circling over the Adriatic. Brantz says he was also told by Sarajevo that all forty were fighter-bombers to be used in massive air strikes. General Nicolai and his military aide in Sarajevo, Colonel Andrew de Ruiter, deny ever saying such a thing.

At 8:55 a.m., Karremans filed his third request for Close Air Support. Sarajevo rejected the request, telling Major Franken that because the Dutch were not one hundred percent sure that the firing on the blocking position was coming from the Serbs, Close Air Support could not be approved.

By 10:30 a.m., forty planes began to circle over the Adriatic, but they were there only for Close Air Support if the Serbs attacked the blocking position. At most, six of them could actually carry out attacks around Srebrenica. The rest were electronic warfare escorts and support planes that were part of the strict new safety standards NATO commanders had put in place since U.S. pilot Scott O’Grady had been shot down on June 2.

What the Dutch didn’t realize was that their blocking position had been attacked by the Serbs. Still convinced that it was a Muslim hand grenade that had blown the Dutch APC off the road near  amila Omanovi

amila Omanovi ’s house at 7:15 a.m., Karremans had not included the incident in the 8:55 a.m. Close Air Support request.

’s house at 7:15 a.m., Karremans had not included the incident in the 8:55 a.m. Close Air Support request.

When Mido Salihovi ’s messenger reached Srebrenica with news of how far south the maneuver unit had pushed the Serbs, he was nearly in tears. “The Serbs are running!” he shouted. “They didn’t even have time to take their cars!” Officers leapt to their feet and shouted in glee. Even the cautious Be

’s messenger reached Srebrenica with news of how far south the maneuver unit had pushed the Serbs, he was nearly in tears. “The Serbs are running!” he shouted. “They didn’t even have time to take their cars!” Officers leapt to their feet and shouted in glee. Even the cautious Be irovi

irovi smiled broadly.

smiled broadly.

The group had listened to the gunfire from the south nervously. “They’re fucking them,” one officer had said, half praying. “I know they’re fucking them.” While they waited, Osman Sulji , Srebrenica’s war president, and Zulfo Tursunovi

, Srebrenica’s war president, and Zulfo Tursunovi , the brigade commander who had barred the Dutch from the Bandera Triangle, had broken into the locker of the abandoned UN Military Observers’ office in the building. For the first time in years, they ate fruit salad and chocolates. The enclave’s British, Dutch and Kenyan UN Military Observers had retreated to the main base in Poto

, the brigade commander who had barred the Dutch from the Bandera Triangle, had broken into the locker of the abandoned UN Military Observers’ office in the building. For the first time in years, they ate fruit salad and chocolates. The enclave’s British, Dutch and Kenyan UN Military Observers had retreated to the main base in Poto ari on Sunday. Their two Bosnian translators stayed in the town and relayed reports on where and how often shells were landing.

ari on Sunday. Their two Bosnian translators stayed in the town and relayed reports on where and how often shells were landing.

Near Kožlje, Salihovi and his men still waited. Some of them tried to move up to the trenches near OP Foxtrot, but shells fired from behind abruptly careened into the hillside. Puzzled, Salihovi

and his men still waited. Some of them tried to move up to the trenches near OP Foxtrot, but shells fired from behind abruptly careened into the hillside. Puzzled, Salihovi and his men hid in the woods. A Serb tank in Pribi

and his men hid in the woods. A Serb tank in Pribi evac had shot at them. A devastating volley of shells and mortars rained down on the Bosnian soldiers who had occupied the hill to Mido’s right, Živkovo Brdo.

evac had shot at them. A devastating volley of shells and mortars rained down on the Bosnian soldiers who had occupied the hill to Mido’s right, Živkovo Brdo.

This dynamic occurred throughout the war in Bosnia. Once Bosnian Muslim infantry gained new territory, long-range Serb artillery would pulverize them. After several hours of shelling, either there were no Bosnians left in the new positions or they had fallen back, unable to fire back at the Serb artillery in the distance. The one hundred soldiers who had volunteered for the counteroffensive hid in houses or behind trees as Serb shells shook the ground beneath them or tore through the branches above them. The number of wounded slowly began to rise.3

The daily briefing convened in UN headquarters in Zagreb at 11 a.m. Force Commander Janvier opened the meeting. “A Kenyan soldier died in a car accident,” he said through a translator. “In BH [Bosnia], the situation is quiet except in Srebrenica. The BSA [Bosnian Serb Army] attacked south to north—in retaliation perhaps for last week’s attack by the BH [Bosnian Army] out of Srebrenica.”4

“I spoke yesterday with General Tolimir,” he continued. “He explained that the Dutch are free and have their weapons. They are in Bratunac and not POWs.”

In truth, all of the Dutch hostages had been disarmed. Twenty were under armed guard in the Hotel Fontana in Bratunac and ten were under armed guard in a house in Mili i. None were allowed to leave.

i. None were allowed to leave.

“The Dutch asked to be taken in by the BSA for their own safety,” Janvier went on. “I demanded the BSA stop their action and hope to talk with the BSA this morning.”

Colonel De Jonge, the chief of operations, then gave a more detailed report on the attack and the situation in Bosnia and Croatia.5

Janvier spoke up after he concluded. “The BH blocked Canadian resupplies to two observation posts, fired rounds against [UN] troops in Sarajevo and killed a [UN] soldier in a deliberate attack in Srebrenica. I will report this to New York,” Janvier pledged. “In Sarajevo, [UN and UNHCR] convoys reached Sarajevo without firing by the BSA.”

Since arriving as Force Commander in February, Janvier had repeatedly criticized the Bosnian Army for launching offensives and sniping at UN troops while blaming it on the Serbs. Janvier’s suspicions about the Muslims were not unusual. Many Western military officers serving in the UN mission felt that the Bosnian Muslims were not the helpless, outgunned victims of Serb “genocide” that the media portrayed. The Muslims were better armed than the press realized and highly effective at getting fabricated or exaggerated accounts of Serb war crimes publicized.

Some officers went further and believed that the Muslims fired shells at their own people to demonize the Serbs and generate international sympathy, including the one that killed seventy-two people in the infamous February 1993 Sarajevo marketplace massacre which led to the creation of the heavy weapons exclusion zone around the besieged capital. No proof of the allegations was ever produced, but suspicion ran deep among some senior French officers and UN officials that the Bosnian Muslims were trying to draw the UN and NATO into waging war against the Serbs.

As the July 10 daily briefing drew to a close, Janvier accused the Bosnians of trying to draw the UN into fighting in Srebrenica.

“I remind everyone that the BH troops are strong enough to defend themselves. Also, access to Srebrenica is not being defended by the Bosnians. The situation is not the same as 1993,” Janvier said. “I’ve just received information that [Bosnian soldiers] are shooting on Dutch troops blocking the route into Srebrenica and shooting at NATO planes over Srebrenica.”

The claim that the Bosnians fired on a plane over Srebrenica was false.6 Serbs may have been firing on the planes, but no Dutch reported seeing Bosnian soldiers shooting at them. The report of the Bosnians firing on the Dutch was apparently a reference to the “Muslim hand grenade” that the Dutch thought had knocked their APC off the road near  amila Omanovi

amila Omanovi ’s house that morning.

’s house that morning.

“The Bosnian Army is trying to push us into a path that we don’t want,” Janvier warned.

Yasushi Akashi agreed. “The BH initiates actions,” he said, “and then calls on the UN and international community to respond and take care of their faulty judgment.”

In a village outside Srebrenica that morning, Hurem Sulji , a fifty-five-year-old Bosnian Muslim, hobbled around his house. The day before, he had watched groups of ten to fifteen women, children and old men walk through the field near his village, Ornica, with growing confidence. All of them said they were fleeing from the southern half of the enclave and were going to the Dutch headquarters in Poto

, a fifty-five-year-old Bosnian Muslim, hobbled around his house. The day before, he had watched groups of ten to fifteen women, children and old men walk through the field near his village, Ornica, with growing confidence. All of them said they were fleeing from the southern half of the enclave and were going to the Dutch headquarters in Poto ari. Sulji

ari. Sulji was sure that once all the refugees got to the Dutch base and the UN commander saw them, he would call for help. The Serbs would be ordered to withdraw, and it would all be over in one or two days. Two days at the most.

was sure that once all the refugees got to the Dutch base and the UN commander saw them, he would call for help. The Serbs would be ordered to withdraw, and it would all be over in one or two days. Two days at the most.

Short and frail, with only wisps of thin brown hair, Sulji had large ears and a big nose. His face was deeply wrinkled and his eyes were brown, soft and round. His right leg was nearly useless.

had large ears and a big nose. His face was deeply wrinkled and his eyes were brown, soft and round. His right leg was nearly useless.

Sulji ’s life had ended more or less twenty years before, on July 3, 1974, when he was working as a carpenter and slipped and fell. His right leg shattered when he hit the concrete three floors below. The doctors in Sarajevo considered amputating it, but instead saved the lifeless limb. He was hospitalized for four months. The neural damage was so severe that he could feel nothing in the leg. It was as if he had been paralyzed. To walk, he locked his knee in place and then slowly put weight on it. After the accident, Sulji

’s life had ended more or less twenty years before, on July 3, 1974, when he was working as a carpenter and slipped and fell. His right leg shattered when he hit the concrete three floors below. The doctors in Sarajevo considered amputating it, but instead saved the lifeless limb. He was hospitalized for four months. The neural damage was so severe that he could feel nothing in the leg. It was as if he had been paralyzed. To walk, he locked his knee in place and then slowly put weight on it. After the accident, Sulji was forced to become a night watchman at one of the factories in Poto

was forced to become a night watchman at one of the factories in Poto ari. He hated the hours, sitting in the dark, and he was never outside, as he had been as a carpenter.

ari. He hated the hours, sitting in the dark, and he was never outside, as he had been as a carpenter.

He and his family were lucky; they lived in the countryside. A mile from the western edge of the enclave and three miles from Srebrenica town, Ornica was relatively safe. There were only eleven households in this tiny Muslim village. Sulji lived with his wife, two daughters, son, son-in-law and two grandchildren. They grew all the food they needed—peppers, onions, garlic, carrots, cabbage. Cornmeal and bread they bartered for salt and sugar with the traders who came once a week from Žepa.

lived with his wife, two daughters, son, son-in-law and two grandchildren. They grew all the food they needed—peppers, onions, garlic, carrots, cabbage. Cornmeal and bread they bartered for salt and sugar with the traders who came once a week from Žepa.

Sulji and three neighbors had worked together to jury-rig a century-old water mill normally used to grind corn. Steel bars and a truck tire held the waterwheel to a cement mixer motor that generated electricity. They built a small dam in the river to make the water run faster, creating more revolutions, and therefore more electricity. Still, their generator produced only enough electricity to power one or two lights or a radio in each of their houses.

and three neighbors had worked together to jury-rig a century-old water mill normally used to grind corn. Steel bars and a truck tire held the waterwheel to a cement mixer motor that generated electricity. They built a small dam in the river to make the water run faster, creating more revolutions, and therefore more electricity. Still, their generator produced only enough electricity to power one or two lights or a radio in each of their houses.

The trick was modulating the amount of electricity. Too much voltage could blow precious fuses and lightbulbs. To watch TV, lights and radios in all four houses were turned off. Sulji or a neighbor would then measure how much current the waterwheel was generating with a voltmeter. The men shouted to their wives to turn on lights in the four houses one by one. Once the meter gave an acceptable reading, it was possible to turn on a television set in a communal living room. There were only two options—state-controlled Bosnian Serb TV from Pale or state-controlled Bosnian government TV from Sarajevo. Sulji

or a neighbor would then measure how much current the waterwheel was generating with a voltmeter. The men shouted to their wives to turn on lights in the four houses one by one. Once the meter gave an acceptable reading, it was possible to turn on a television set in a communal living room. There were only two options—state-controlled Bosnian Serb TV from Pale or state-controlled Bosnian government TV from Sarajevo. Sulji usually watched the evening news from Sarajevo, and then turned the TV and VCR over to the younger people.

usually watched the evening news from Sarajevo, and then turned the TV and VCR over to the younger people.

If the outbreak of the war surprised Sulji , its viciousness astonished him. Like so many others, he had talked with Serb friends as tensions rose in Bosnia. A few days before Arkan’s soldiers arrived in Srebrenica in April 1992, he was chatting with Rajko Paji

, its viciousness astonished him. Like so many others, he had talked with Serb friends as tensions rose in Bosnia. A few days before Arkan’s soldiers arrived in Srebrenica in April 1992, he was chatting with Rajko Paji , a Serb friend from a neighboring village. “It’s not going to be good,” Paji

, a Serb friend from a neighboring village. “It’s not going to be good,” Paji had told him. The next day, the Serb cattleman and his family gathered their belongings, abandoned their house and moved to Serbia. Sulji

had told him. The next day, the Serb cattleman and his family gathered their belongings, abandoned their house and moved to Serbia. Sulji had always thought his friend had been trying to warn him.

had always thought his friend had been trying to warn him.

As the crippled ex-carpenter hobbled around his house that morning, his idyll was barely disturbed by the distant thunder of artillery. Sulji knew Naser Ori

knew Naser Ori was not in the enclave, but he had no doubts that the UN would defend Srebrenica. There was no one else to stop the Serbs. The town’s soldiers had turned over all their weapons. The Dutch commander just needed to call UN headquarters and ask for help.

was not in the enclave, but he had no doubts that the UN would defend Srebrenica. There was no one else to stop the Serbs. The town’s soldiers had turned over all their weapons. The Dutch commander just needed to call UN headquarters and ask for help.

Lieutenant Vincent Egbers scanned the hills south of the enclave. He had heard the firefights erupt early that morning but was unable to determine exactly what was happening. The Muslims sitting on the hill a few feet above him had still not fired the enclave’s lone artillery piece. Ramiz Be irovi

irovi ’s orders had not changed. The soldiers were to wait for the UN to defend them.

’s orders had not changed. The soldiers were to wait for the UN to defend them.

Just after 11 a.m., Meho Malagi , the brother of the man who had held off the Serb tanks in Bibi

, the brother of the man who had held off the Serb tanks in Bibi i the previous day, watched the Serb tank in Pribi

i the previous day, watched the Serb tank in Pribi evac fire on the town. A puff of smoke left the barrel. Something—the sound of the shell or his instinct—told him it was coming. “Grenade!” he shouted in Bosnian. Egbers and his men never saw it coming.

evac fire on the town. A puff of smoke left the barrel. Something—the sound of the shell or his instinct—told him it was coming. “Grenade!” he shouted in Bosnian. Egbers and his men never saw it coming.

A twenty-foot plume of smoke and dust rose from the ground in front of them. Bits of rock and shrapnel whizzed through the air. The Dutch dove to the ground. The shell had landed twenty yards away.

A second round landed just behind them. Rocks, dirt and shrapnel showered down. The Dutch leapt into the APCs and the jeep parked on the bluff. A third explosion followed. The earth shook. Bits of shrapnel could be heard pinging off the sides of the APCs. In the back of the jeep, blood poured from the British Forward Air Controller’s elbow, neck and knee. In total disarray, the Dutch turned the vehicles around. A fourth shell impacted and the Dutch sped down the dirt road until they were hidden by trees, out of sight of the Serb gunners.

At almost the same time, a UN salvage APC arrived on the road overlooking the town to tow the APC driven off the road that morning. As it prepared to pull the vehicle up the embankment, a loud explosion ripped through the trees thirty yards away. The Dutch scrambled into the salvage APC and sped back to the UN base. The driver was so panicked that he drove the vehicle into a wood pile in Srebrenica town, injuring some of the Dutch soldiers inside. Several hours later, the Dutch realized that the tank in Pribi evac had been attacking them; it was not a Muslim with a hand grenade.

evac had been attacking them; it was not a Muslim with a hand grenade.

Up ahead, Lieutenant Egbers checked if everyone was in the APC. He radioed Captain Groen. Egbers’ mind was following patterns that had been drilled into it in training. He felt as if he’d just been in a car accident. His body was trembling. His men were in shock. They couldn’t hear each other because their ears were ringing so loudly. The medic started bandaging the wounded peacekeeper. He had been hit by shrapnel, but the wounds weren’t serious. Shrapnel had torn through the spare tire on the back of the jeep. Egbers was astounded that no one had died.

His soldiers started cursing the UN. They were stationed in hell compared with the other peacekeepers. They had heard about how the peacekeepers in the UN headquarters in Zagreb lived. All the food and beer they wanted, tennis courts and swimming pools on the main base at Camp Pleso. The Dutch received no extra pay for risking their lives in Srebrenica. The UN didn’t even supply them properly. Food, fuel and ammunition could all have been air-dropped into the enclave, but the Dutch had been left there to rot. None of them had come to Bosnia to die.

Egbers couldn’t make radio contact with Groen, but he was able to radio the men in OP Charlie on the far western edge of the enclave, who relayed to Groen what had happened. When Groen asked Egbers if he was sure the Serb tank was targeting him, Egbers balked. The Serb tank could have been firing at the Muslim artillery piece thirty yards above them. The Muslims could have been firing the gun when the Serbs fired and masking the noise. Egbers wasn’t sure.

When the Dutch deputy commander, Major Robert Franken, contacted his superiors in Tuzla about the shelling attack, he was told it did not qualify as an attack on the blocking position. Baffled, he assumed it was because of the nearby Muslim artillery piece. He still thought it was the Muslims who had fired on the two UN APCs on the road above  amila Omanovi

amila Omanovi ’s house, not the Serbs.7

’s house, not the Serbs.7

Another opportunity to pressure Janvier, Akashi and other reluctant UN commanders in Zagreb to launch Close Air Support had been missed.

In Srebrenica town, Ramiz Be irovi

irovi was having difficulty finding reinforcements to send south. As the shelling intensified, each brigade commander worried that his own line would collapse, exposing his own village, house and family to the Serbs.

was having difficulty finding reinforcements to send south. As the shelling intensified, each brigade commander worried that his own line would collapse, exposing his own village, house and family to the Serbs.

Few men had shown up for the counteroffensive that morning. In an enclave which had 3,000 soldiers in 1993, there were only 100 volunteers. Many men were insulted by Be irovi

irovi ’s offer of 200 deutsche marks and food for their families. When they’d needed food a week ago, the town’s corrupt leaders had hoarded it for profit, the men complained. Now that the town’s leaders needed their help, they were doling out food and money. In the end, the men leading the counterattack with Mido Salihovi

’s offer of 200 deutsche marks and food for their families. When they’d needed food a week ago, the town’s corrupt leaders had hoarded it for profit, the men complained. Now that the town’s leaders needed their help, they were doling out food and money. In the end, the men leading the counterattack with Mido Salihovi , Veiz Šabi

, Veiz Šabi and Ibro Dudi

and Ibro Dudi went out of personal loyalty to their commanders. The enclave’s long-running divisions were widening.

went out of personal loyalty to their commanders. The enclave’s long-running divisions were widening.

Approximately 70 percent of the population consisted of refugees from villages already held by the Serbs. Many of the refugees were not motivated to fight. No matter what the politicians in Sarajevo said, most men fought to defend their village, house and family, and not for the ideal of an independent Bosnia. With their houses already destroyed, many refugees felt they had nothing to fight for in Srebrenica; they were eager to go to Tuzla in Bosnian government-controlled central Bosnia.

Then there was an entirely separate class of people who dominated the local government, lived in larger homes and generally had more food than most. They controlled the few jobs in town. They were those with close ties to Naser Ori .

.

Not surprisingly, few people trusted the town’s leaders. Stories of corruption were rife, and whether true or not, they were believed.

After being adored by nearly all of the town for his heroics in 1992 and 1993, Naser Ori was seen in a different light by some in the town in the following years. Many still believed that Naser was clean but those around him were corrupt. But others said he was the head of a vast, highly profitable black-marketeering enterprise.8 Naser’s soldiers now spent most of their time hauling goods and food back and forth from Žepa. It was a lucrative trade.

was seen in a different light by some in the town in the following years. Many still believed that Naser was clean but those around him were corrupt. But others said he was the head of a vast, highly profitable black-marketeering enterprise.8 Naser’s soldiers now spent most of their time hauling goods and food back and forth from Žepa. It was a lucrative trade.

With Naser Ori and a few families dominating it, the enclave’s political structure was basically feudal. Ori

and a few families dominating it, the enclave’s political structure was basically feudal. Ori ’s associates were named the town’s war president and mayor in 1992. The offices rotated among several men, but all of them were seen as loyal to, or controlled by, Ori

’s associates were named the town’s war president and mayor in 1992. The offices rotated among several men, but all of them were seen as loyal to, or controlled by, Ori .9 It was rumored that the mayor, the war president and other officials in the municipal government had sold much of the UN humanitarian aid. The salt, sugar, coffee and gasoline sold at a tremendous profit on the black market. They hoarded rice and other foodstuffs, it was said, in municipal warehouses to drive up prices. Municipal officials of course denied the rumors; few believed them.

.9 It was rumored that the mayor, the war president and other officials in the municipal government had sold much of the UN humanitarian aid. The salt, sugar, coffee and gasoline sold at a tremendous profit on the black market. They hoarded rice and other foodstuffs, it was said, in municipal warehouses to drive up prices. Municipal officials of course denied the rumors; few believed them.

Since his helicopter had been shot down on May 7, Ramiz Be irovi

irovi had been at the center of a storm of rumors. Be

had been at the center of a storm of rumors. Be irovi

irovi carried 150,000 deutsche marks ($100,000) in cash into the enclave from a charity in Sarajevo. The money was to be distributed to the orphans of the roughly 1,500 soldiers from Srebrenica killed during the war. Naser Ori

carried 150,000 deutsche marks ($100,000) in cash into the enclave from a charity in Sarajevo. The money was to be distributed to the orphans of the roughly 1,500 soldiers from Srebrenica killed during the war. Naser Ori was supposed to later carry in a large amount of deutsche marks that was back pay for soldiers.10

was supposed to later carry in a large amount of deutsche marks that was back pay for soldiers.10

Be irovi

irovi said he distributed 100,000 deutsche marks ($70,000) of the charity money to four of the five unofficial “brigades” in the town. When the attack started in early July he said he had 50,000 deutsche marks ($35,000) left that he said he still intended to distribute.11 The rumor was that Be

said he distributed 100,000 deutsche marks ($70,000) of the charity money to four of the five unofficial “brigades” in the town. When the attack started in early July he said he had 50,000 deutsche marks ($35,000) left that he said he still intended to distribute.11 The rumor was that Be irovi

irovi had distributed none of the money and that he and his wife had pocketed it all. Zulfo Tursunovi

had distributed none of the money and that he and his wife had pocketed it all. Zulfo Tursunovi , the brigade commander in the southwest, denied it, but he was rumored to run his own black-market operation, as were several of the enclave’s other officers.

, the brigade commander in the southwest, denied it, but he was rumored to run his own black-market operation, as were several of the enclave’s other officers.

The news disseminated to the outside world was frequently false. In impassioned shortwave radio interviews, for example, Srebrenica’s leaders reported that people were starving. Sulji , the war president, told Sarajevo radio on July 6 that thirteen people had died of starvation due to food shortages. But according to Médecins Sans Frontières officials within the enclave, food was in very short supply at the time, but the story was blatantly untrue.

, the war president, told Sarajevo radio on July 6 that thirteen people had died of starvation due to food shortages. But according to Médecins Sans Frontières officials within the enclave, food was in very short supply at the time, but the story was blatantly untrue.

Médecins Sans Frontières also feuded with Avdo Hasanovi , the director of the local hospital. Dr. Hasanovi

, the director of the local hospital. Dr. Hasanovi wanted the aid group to allow him to distribute its free medicines. But Hasanovi

wanted the aid group to allow him to distribute its free medicines. But Hasanovi , a member of Ori

, a member of Ori ’s inner circle, allegedly sold the medicine on the town’s black market. He was even reputed to have charged people for performing operations, such as abortions,12 which was unheard of in siege conditions and against the Hippocratic oath. He denied all of the charges; few believed him.

’s inner circle, allegedly sold the medicine on the town’s black market. He was even reputed to have charged people for performing operations, such as abortions,12 which was unheard of in siege conditions and against the Hippocratic oath. He denied all of the charges; few believed him.

The sale of UN aid and rampant black-market activities were not unusual for Bosnia. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) aid operation in the former Yugoslavia was the first ever to allow local authorities to distribute the aid they received. UNHCR predictions that Srebrenica, Sarajevo and other enclaves were on the verge of starving were always based on loose estimates. UNHCR officials were never sure exactly how much food government officials had actually distributed versus stockpiled, given to the army or sold on the black market.

In each of the five surrounded enclaves and along key supply routes in Bosnia, the war, for some, was enormously profitable. Hundreds of thousands of dollars were made by leaders, smugglers and racketeers.

Opposition was not tolerated in the enclave and few people dared to challenge Naser. He and his men were primarily from small villages around Srebrenica and were viewed as dangerous primitives by some of the original inhabitants of the town. When the Bosnian government replaced the entire senior command in the enclave of Goražde in the winter of 1994–95, hope had risen in some quarters that the same would soon happen in Srebrenica.

In June, three leading opponents of Ori were ambushed in Srebrenica. Ibran Mustafi

were ambushed in Srebrenica. Ibran Mustafi , a member of the Muslim nationalist Party of Democratic Action and the town’s representative to the national assembly, was wounded in the nighttime attack. Ori

, a member of the Muslim nationalist Party of Democratic Action and the town’s representative to the national assembly, was wounded in the nighttime attack. Ori had accused him of being a coward and the leader of a pro-Serb “fifth column” trying to destabilize the enclave.13

had accused him of being a coward and the leader of a pro-Serb “fifth column” trying to destabilize the enclave.13

A bullet grazed Mustafi ’s face, leaving a scar running from the corner of one of his eyes to his hairline. Hamed Salihovi

’s face, leaving a scar running from the corner of one of his eyes to his hairline. Hamed Salihovi , Srebrenica’s police chief before the war, wasn’t so lucky. He died in the attack. A third person, Mohamed Efendi

, Srebrenica’s police chief before the war, wasn’t so lucky. He died in the attack. A third person, Mohamed Efendi , survived unscathed.14

, survived unscathed.14

As the shelling intensified in the south, Be irovi

irovi was finally able to find some reinforcements. Accounts of how many men were sent and exactly what time they left vary widely,15 but the effort was too little too late. Lacking the authority and charisma of Naser Ori

was finally able to find some reinforcements. Accounts of how many men were sent and exactly what time they left vary widely,15 but the effort was too little too late. Lacking the authority and charisma of Naser Ori , Be

, Be irovi

irovi was losing control of the enclave’s soldiers.

was losing control of the enclave’s soldiers.

By noon, Egbers had found a new position where the view to the south was nearly as good as it had been on the exposed curve. But he still did not have direct radio contact with Captain Groen in Srebrenica. The Serbs had probably targeted the bluff in case a Forward Air Controller was there.

Their strategy had worked in more ways than one. The wounded British Forward Air Controller had been evacuated, and the remaining Forward Air Controller—Sergeant Voskamp of the Dutch contingent—was on the verge of a nervous breakdown. He sat silently in the APC, not speaking to the soldiers who tried to get him to talk. He refused to eat or drink. When he finally spoke, he vowed not to go back to the exposed curve. “You guys are crazy,” he said. “You guys are playing with your lives.”

Egbers couldn’t believe it. The other Dutch Forward Air Controller, Sergeant Roelof Groenendal, had fallen to the ground and started screaming, “I don’t want to die, I don’t want to die,” on Saturday as he walked toward the APC that would carry him from Poto ari to Srebrenica. Now Egbers and his men were risking their lives so this Forward Air Controller could be in position. They desperately tried to calm him. Without a Forward Air Controller, air strikes could not be carried out.

ari to Srebrenica. Now Egbers and his men were risking their lives so this Forward Air Controller could be in position. They desperately tried to calm him. Without a Forward Air Controller, air strikes could not be carried out.

Egbers was frightened, but he was willing to go back up to his former position. After the shelling that morning, he had trembled for several minutes. He calculated in his head how he wanted his $60,000 life insurance policy divided if he died. He wrote down the names of his beneficiaries and the amounts and tucked the information into his uniform where it could be easily found.

Gun battles were erupting again along the road. The Serbs seemed to withdraw their forces from the enclave every night so their soldiers could go celebrate in Bratunac. This was nothing like World War II, Egbers thought; fighting was like a nine-to-five job for these people. Unaware of the Muslim counteroffensive, he remained unimpressed with the resistance the Muslims were putting up. The Serbs were attacking toward Srebrenica and shelling the enclave with everything they had, but there were still no NATO planes overhead. Sometimes fear gave way to simple exasperation.

Egbers and a few of his men walked back up the hill to the Muslim artillery position. He wanted to know if the gun had fired, and if that was why the Serbs targeted the position. The Muslim who had scribbled “30 equals 30,000” lay on the ground surrounded by his men. Blood poured from a shrapnel wound in his stomach. His soldiers carried him away on a makeshift stretcher.

The mood of the Bosnians had darkened. They pointed at Egbers’ two APCs nestled in the trees below. Another conversation began in Serbo-Croatian, German and broken English.

“Why don’t you shoot at the Serbs?” they asked Egbers.

“Why don’t you shoot?” Egbers answered. He pointed at the gun and wrote on the paper that his antitank missile had a range of only 800 yards. He pointed at the Bosnians’ artillery piece and wrote 3,000 yards.

The Muslims shook their heads. Their orders had still not changed. Their forty shells were unused. Srebrenica’s only artillery piece had still not fired.16

In the enclave’s northwest corner, Mevludin Ori was waiting eagerly in his home village of Lehovi

was waiting eagerly in his home village of Lehovi i for the NATO planes to go into action. Since the first day of the attack when he had watched the Serb shelling from Mount Zvijezda, he had been waiting for NATO’s high-tech arsenal to be unleashed. Distant cousins who lived in the Swedish Shelter Project arrived that morning telling exaggerated stories of dozens of tanks and thousands of soldiers from neighboring Serbia swarming the southern edge of the enclave. Mevludin believed them, but he knew the Dutch and NATO had the firepower to crush the Serbs.

i for the NATO planes to go into action. Since the first day of the attack when he had watched the Serb shelling from Mount Zvijezda, he had been waiting for NATO’s high-tech arsenal to be unleashed. Distant cousins who lived in the Swedish Shelter Project arrived that morning telling exaggerated stories of dozens of tanks and thousands of soldiers from neighboring Serbia swarming the southern edge of the enclave. Mevludin believed them, but he knew the Dutch and NATO had the firepower to crush the Serbs.

Mevludin himself had been caught by a Dutch patrol the previous summer. His unit regularly carried out secret patrols along the enclave’s northwestern front line to check for Serb raiding parties entering the safe area. They patrolled with semiautomatic rifles—something Muslim soldiers were not allowed to have in the demilitarized enclave. The precious rifles were hidden at night and shared by the unit’s soldiers. His thirty-man platoon had only ten rifles.

Just before the Dutch caught him, Mevludin was leaning against a tree and dozing in the hot afternoon sun. When one of his friends shouted, “Look out, it’s UNPROFOR!” he thought it was a joke they often played on each other. But Dutch peacekeepers abruptly encircled Mevludin and pointed their rifles at him. In his hands was one of the most valuable items in the enclave—a Kalashnikov assault rifle that had been captured from the Serbs during the attack on Kravica. Mevludin at first tried to play dumb, quickly smiling and trying to shake hands with the Dutch soldier. “Rifle!” the peacekeeper said in Bosnian. “Rifle!”

There were at least eight Dutch. Mevludin knew he wouldn’t survive if he fought. Grudgingly, he handed the Kalashnikov over. Mevludin knew he would be ridiculed by his unit for losing it. He despised the greedy Dutch and had heard that they received ten days’ vacation for every rifle they seized.17 Mevludin couldn’t believe they were taking away his right to defend himself. One year after losing the rifle, he still loathed the Dutch. But he expected the UN to be as hard on the Serbs as they had been on him.

By the early afternoon, Captain Groen and another officer had counted thirty-two consecutive explosions. A multiple rocket launcher was clearly firing on the town. Groen wondered what had happened to the NATO air strikes.

The only good news had come at noon. The Dutch from OP Delta who were surrounded by the Muslims in Kutezero the day before finally arrived in Srebrenica. Groen had worried more about the fate of the ten Dutch held by the Muslims than about the thirty Dutch held by the Serbs. The shelling continued as the afternoon crawled by; no NATO planes appeared.

By 3 p.m., the new positions the Muslims had taken in the south of the enclave were nearly empty. In the dynamic of the war, the Bosnian Serb advantage in tanks and artillery was so overwhelming that the Muslims did not have enough time to dig adequate bunkers or simply failed to do so.

Ten of the approximately thirty Muslim soldiers on Živkovo Brdo had been wounded by shrapnel from distant Serb tanks and artillery. Demoralized by their inability to return fire and fearing more casualties, the group pulled back.18 Mido Salihovi and most of his men had left their position on Kožlje at some point that morning. Salihovi

and most of his men had left their position on Kožlje at some point that morning. Salihovi , confident the Serbs would not counterattack, had waited for several hours for reinforcements to arrive. When none did, he left ten men to hold the position and returned to the town to rest and meet with Ramiz Be

, confident the Serbs would not counterattack, had waited for several hours for reinforcements to arrive. When none did, he left ten men to hold the position and returned to the town to rest and meet with Ramiz Be irovi

irovi .19

.19

When a Serb tank backed by 100 infantry began to advance up the asphalt road, it met only token resistance.

Egbers watched the tank inch north. There was still no sign of NATO planes. At 4:30 p.m., he radioed that the Serbs had passed Bibi i and were only a half mile south of the town center. Still afraid the Muslims would attack the Dutch, Groen had not sent APCs down the main asphalt road to block the Serb advance. Thirty minutes later, Groen ordered Egbers to return to base. He was worried that the Serbs would soon pass Bravo One and the Dutch would be captured.

i and were only a half mile south of the town center. Still afraid the Muslims would attack the Dutch, Groen had not sent APCs down the main asphalt road to block the Serb advance. Thirty minutes later, Groen ordered Egbers to return to base. He was worried that the Serbs would soon pass Bravo One and the Dutch would be captured.

As Egbers sped down the hill toward Srebrenica, he heard bullets ping off the armor of his APC. The gunner grabbed his arm and disappeared inside the vehicle. Convinced the Dutch were retreating yet again, the Muslim soldiers manning the artillery piece were firing at them.

Once they reached town, Egbers was shocked by the anarchy. Thousands of people packed the streets. Hundreds of panicked Muslims surrounded them, shouting “Fuck you!” in English. Heavily armed Muslim men pointed rocket-propelled grenades and shouted at Egbers to drive south toward the Serbs. Others tried to leap onto the vehicle and use its .50 caliber machine gun. He and his men fought them off.

Egbers slowly drove south. Muslim men armed with rocket-propelled grenades followed him. His orders were to reinforce the two other APCs in the market near the southern edge of the town. Nervously eyeing the Muslim soldiers, he readily complied.

Four thousand people from neighboring villages and the Swedish Shelter Project filled the town. In the market, Muslim women and children clustered around Dutch APCs, hoping the Serbs would be less likely to shell peacekeepers. They circled the UN compound and begged sentries to let them in. Thousands of others huddled in the stairwells of apartment buildings trying to avoid the random shells.

Chaos reigned. Men broke into stores and looted. Muslim soldiers sat with their families, taunted the Dutch or wandered aimlessly. Naser Ori ’s absence was glaring.

’s absence was glaring.

In the post office, the town’s leaders were divided. Ramiz Be irovi

irovi , the acting commander, still believed NATO air strikes would come. Fahrudin Salihovi

, the acting commander, still believed NATO air strikes would come. Fahrudin Salihovi , the mayor, thought the Muslims should invite the Dutch commander, Colonel Karremans, to a meeting, take him hostage and threaten to kill him if NATO didn’t attack.

, the mayor, thought the Muslims should invite the Dutch commander, Colonel Karremans, to a meeting, take him hostage and threaten to kill him if NATO didn’t attack.

In the southern end of Srebrenica,  amila Omanovi

amila Omanovi was trying to have dinner in her house with her husband and brother. After seeing the Dutch APCs shelled, there had been no other indications that Serb soldiers were so close. She had spent the day doing busywork in the house, desperate to keep her mind off the situation around her.

was trying to have dinner in her house with her husband and brother. After seeing the Dutch APCs shelled, there had been no other indications that Serb soldiers were so close. She had spent the day doing busywork in the house, desperate to keep her mind off the situation around her.

They ate in silence.

“They’re behind you!” a man suddenly shouted from outside the house. “Get out of the house!”

amila, her brother and her husband froze.

amila, her brother and her husband froze.

“They’re close!” he cried. “Get away!”

amila and Ahmet tore out of the room. Her brother, Abdulah, ran to the balcony and jumped to the yard ten feet below. She and her husband sprinted down the stairs and burst out the front door. As the three crossed the street and headed toward the tree-covered stream, bullets hit the side of their house. Only later did they realize what had happened. The Serbs were on the ridge overlooking the southern end of town. From the top of it they had a clear shot at

amila and Ahmet tore out of the room. Her brother, Abdulah, ran to the balcony and jumped to the yard ten feet below. She and her husband sprinted down the stairs and burst out the front door. As the three crossed the street and headed toward the tree-covered stream, bullets hit the side of their house. Only later did they realize what had happened. The Serbs were on the ridge overlooking the southern end of town. From the top of it they had a clear shot at  amila’s house.

amila’s house.

BOSNIAN SERB ADVANCE, JULY 10, 1995

At 6 p.m., a panicked voice filled the Dutch operations room in Srebrenica.

“Romeo, this is Hotel!” Dutch peacekeeper Sergeant Frank Struik shouted over the radio. “A company of BSA infantry are on the hill overlooking Srebrenica! I repeat, eighty BSA infantry are on the hill overlooking Srebrenica town!”

It was happening, Groen thought. Srebrenica was falling.

“Hotel, this is Romeo,” Groen shouted. “Are they advancing toward the town?”

“Negative,” answered Sergeant Struik, who was on a hill just east of town. “They’re lined up on the hill facing the town but not moving.”

The Serbs were halfway down the hill overlooking the town center. They were 400 yards above his APCs in the market. How had they gotten so close? Groen wondered. Where were the Muslims?

Groen radioed the APCs in the market and ordered them to watch for any signs of a Serb advance. He ordered two other Dutch APCs to pull back from their positions south of the market and join the others already there. He checked to see if the mortar in the compound was ready, and then waited for the Serbs to make the next move.

Ibran Malagi stared at the Serbs through the scope of his sniper rifle. His fingers were burnt from trying to fixed the jammed machine gun on Saturday, but he could still shoot. Crouched behind the base of a power pole at the southern end of Srebrenica, he saw three Serbs moving in a clearing about 1,000 yards up the hill. Malagi

stared at the Serbs through the scope of his sniper rifle. His fingers were burnt from trying to fixed the jammed machine gun on Saturday, but he could still shoot. Crouched behind the base of a power pole at the southern end of Srebrenica, he saw three Serbs moving in a clearing about 1,000 yards up the hill. Malagi fired three shots and ran across the road. His wife, along with eight soldiers, followed him. They reached a house they could hide in, and momentarily relaxed.

fired three shots and ran across the road. His wife, along with eight soldiers, followed him. They reached a house they could hide in, and momentarily relaxed.

Mido Salihovi had banged on Malagi

had banged on Malagi ’s front door at 5 p.m. to tell him the Serbs were on the edge of town. A hodgepodge of two dozen men from Mido’s and Ibro Dudi

’s front door at 5 p.m. to tell him the Serbs were on the edge of town. A hodgepodge of two dozen men from Mido’s and Ibro Dudi ’s units were taking up positions on the southern tip of the town. Malagi

’s units were taking up positions on the southern tip of the town. Malagi ’s twenty-one-year-old bride had insisted on coming with them.

’s twenty-one-year-old bride had insisted on coming with them.

Five hundred yards up the hill, a house was burning. Malagi hoped this was the Serbs’ most advanced position. Mido was leading a second group of soldiers who were taking positions along the stream that flowed into town from the south. He peered through his sniper sight and saw a Serb standing in the clearing 1,000 yards away. Malagi

hoped this was the Serbs’ most advanced position. Mido was leading a second group of soldiers who were taking positions along the stream that flowed into town from the south. He peered through his sniper sight and saw a Serb standing in the clearing 1,000 yards away. Malagi traded his sniper rifle for a Kalashnikov assault rifle. He didn’t know how many other Serbs were nearby.

traded his sniper rifle for a Kalashnikov assault rifle. He didn’t know how many other Serbs were nearby.

His group decided to split up and try to move closer to the burning house, as Malagi , his wife and two soldiers walked down a small street hidden from the Serbs’ view. Mido’s group began shooting near the stream and ran out from behind the house. A Serb soldier scrambled for cover in the woods. Malagi

, his wife and two soldiers walked down a small street hidden from the Serbs’ view. Mido’s group began shooting near the stream and ran out from behind the house. A Serb soldier scrambled for cover in the woods. Malagi fired all thirty of his bullets, knowing he wouldn’t hit anything. His goal was to scare the Serbs into thinking that taking the town wouldn’t be easy.

fired all thirty of his bullets, knowing he wouldn’t hit anything. His goal was to scare the Serbs into thinking that taking the town wouldn’t be easy.

The firing died down. The Serbs had disappeared. Malagi and his wife silently smoked a cigarette. He trusted Mido completely, confident that the Serbs would never enter Srebrenica. But what he didn’t know was that a second, larger group of Serb soldiers was advancing toward the town a half mile to the north. The only thing standing in their way was the Dutch.20

and his wife silently smoked a cigarette. He trusted Mido completely, confident that the Serbs would never enter Srebrenica. But what he didn’t know was that a second, larger group of Serb soldiers was advancing toward the town a half mile to the north. The only thing standing in their way was the Dutch.20

At 6:30 p.m., Sergeant Struik started shouting over the radio again.

“Romeo, this is Hotel!” Struik implored. “BSA is advancing! BSA is advancing!”

Groen had prepared for this moment dozens of times. He ordered his second-in-command in the market to fire over the heads of the Serbs with the APC’s .50 caliber machine gun. He ordered the mortar in the compound to begin firing as well, but only to send up flares.

Bedlam erupted in the market. Instead of cheering, confused Muslim soldiers hurled themselves at the Dutch vehicles, screaming, “Stop! Stop! Those are our soldiers!” The Dutch kept firing. OP Hotel instructed the mortar to adjust its fire. The flares were now falling directly over the heads of the advancing Serb infantry. Still, they came.

Groen wanted his men to shoot directly at the Serbs only as a last resort. He thought that if it came to a battle, the Dutch could not stop the Serbs. The best the Dutch could do was to try not to antagonize the Serbs or lose their status as neutral UN observers. As long as the Serbs still thought the Dutch were neutral, they could escort convoys of fleeing civilians and, he hoped, the Serbs would not fire on them.

The Dutch continued to fire, and the Serbs continued to march downhill. The frightened women and children gathered around Groen’s compound finally broke through the fences. Hundreds of women and children swarmed in. Groen screamed for soldiers to clear them out.

The command center of the Dutch headquarters in Poto ari came on the radio. “Be ready for an air strike.” The blocking position was clearly being attacked. The trip wire created in Zagreb two days earlier had finally been triggered. Colonel Karremans was requesting Close Air Support.

ari came on the radio. “Be ready for an air strike.” The blocking position was clearly being attacked. The trip wire created in Zagreb two days earlier had finally been triggered. Colonel Karremans was requesting Close Air Support.

The request for Close Air Support reached Sarajevo at 7:15 p.m. Knowing how hesitant Janvier was to use airpower, General Nicolai had denied any request he thought Janvier would not approve. He had waited for a clear-cut signal that Zagreb could not question. This was it. The Dutch general took the request to the acting UN commander in Bosnia, General Hervé Gobilliard, and recommended that it be approved. Gobilliard signed the form immediately.

In Zagreb, Colonel De Jonge received the request at 7:30 p.m. He had been waiting for this moment since he came up with the blocking position idea. De Jonge rushed into the office of Force Commander Janvier and announced that a company of Serb infantry was on a hill overlooking Srebrenica. The Serbs were advancing toward the town. The Dutch blocking position was firing over their heads.

Janvier, who was notoriously indecisive, hesitated. The French general called a meeting of his Crisis Action Team. The forms for the Close Air Support, code-named Blue Sword, were ready. They needed only Janvier’s signature. Yasushi Akashi was in the Croatian city of Dubrovnik for the day and had delegated the authority to approve Close Air Support to Janvier.

By 7:50 p.m., Janvier’s ornate, wood-paneled office, located on the third floor of Building A in the UN headquarters complex in tranquil Zagreb, was filled with the senior military and civilian leadership of the UN mission. Akashi was represented by his special assistant, John Almstrom.

General Ton Kolsteren, the chief of staff, opened the meeting. “Fifteen minutes ago, sixty to eighty BSA infantry attacked the southern end of Srebrenica town. Two tanks are one and a half kilometers behind them with three trucks and they are moving toward the confrontation line.”21

“How soon can the planes be ready?” asked Janvier, speaking through his interpreter.

“In less than an hour,” answered Colonel Cranny Butler, of the U.S. Air Force, the acting NATO liaison officer.

“We can ask them to change to cockpit standby,” said Colonel Robert, the UN’s chief of air operations.

“Have them stand next to the cockpits,” Janvier said.

The NATO liaison officer left the room.

“Last night we issued an ultimatum,” Janvier said. “They’ve fired on it, but the problem is we have no targets.”

“We have two tanks, we don’t need a smoking gun,” De Jonge retorted. He was referring to a nuance in UN rules that allowed NATO Close Air Support to destroy a tank that was approaching a UN position in a hostile manner even if it had not fired yet.

“If the TACPs [Forward Air Controllers] can’t see them we can change to an airborne Forward Air Controller,” said air operations chief Robert.

“We have two TACPs in the area,” De Jonge said.

“We can also spot artillery from the air,” added Robert.

“Are we in a SAM ring?” Janvier asked, referring to surface-to-air missiles only a few miles away from Srebrenica in Serbia and in the Bosnian Serb Army headquarters in Han Pijesak.

“We’re not sure, but we’d go in with a formation that included SEAD [Suppression of Enemy Air Defenses] planes,” Robert replied.

“Would there be any preemptive strikes against SAMs?” inquired Colonel Thierry Moné, one of Janvier’s military aides.

“Not unless they locked on to us,” Robert answered.

“What is the Dutch government’s position?” Janvier asked General Kolsteren. Many of them expected the Serbs to threaten to kill the thirty Dutch hostages if Close Air Support was carried out.

“It is focused on avoiding casualties among its own soldiers,” Kolsteren responded. Janvier asked Kolsteren to telephone the Dutch government to confirm their position on the use of Close Air Support.

“What do you recommend?” Janvier asked De Jonge.

“Because you made a strong statement to Mladi yesterday and he is countering it, I believe you must launch CAS [Close Air Support],” De Jonge said.

yesterday and he is countering it, I believe you must launch CAS [Close Air Support],” De Jonge said.

“I agree that the troops are at risk,” added Robert. “Although there is a risk to those detained, we must act.”

“There’s no choice if troops are under attack,” said Almstrom, Akashi’s deputy. “If they’re not under attack, it’s different. Then the question is how much shelling can civilians stand? There’s also a problem being near FRY [Serbian] airspace. We don’t need to wait for the SRSG [Akashi]. We only need him to authorize air strikes not CAS.”

“It is absolutely necessary to speak with Mr. Akashi,” Janvier said.

Colonel Butler, the NATO liaison officer, entered the room. Butler said he had spoken to the Coordinated Air Operations Center in Naples, Italy. After having planes circle over the Adriatic from 10:30 a.m. to 2 p.m. that day without being called on, the head of NATO’s southern command, U.S. admiral Leighton Smith, said he needed a signed Close Air Support request before he would launch more planes.

“Are their planes on alert?” Janvier asked.

“If the Force Commander calls, the planes will be ready,” responded Butler.

“Despite the risks, it’s a situation where CAS is necessary,” said Colonel François Dureau, Janvier’s military assistant. “But the targets must be confirmed. The FAC [Forward Air Controller] has the last word on launching the attack.”

Janvier asked to have a call placed to Sarajevo so he could speak with General Gobilliard, the acting UN commander in Bosnia, who had already approved the request. Gobilliard was not in and Janvier did not want to speak to General Nicolai, the Dutch chief of staff.

Janvier’s assistant military assistant, Colonel Moné, was the first to oppose the request. “I’m in favor of CAS, but not tonight. Once the BSA infantry advances there will be confusion. There’s also a problem with targets. It’s better to do it tomorrow morning.”

The meeting was interrupted. Janvier had a phone call. He went into an adjacent room with Moné.22

Colonel De Jonge began to fidget. The light outside was fading. The debate continued without Janvier.

“We can also attack infantry with aircraft,” said air operations chief Robert. “We need F-18s swooping down right now!”

“I agree. We need action,” said General Kolsteren. “I don’t agree with Moné.”

“The aircraft will choose their targets based on attackability and economy of effort,” said Robert. “It’s always better to choose a single target like a tank; infantry requires several passes. It’s about a twenty-minute flight. NATO would love the ability to do its job.”

As Colonel Moné came out of the adjacent room, Janvier was heard raising his voice to whomever he was speaking to. It was a heated discussion. At 8:30 p.m., General Gobilliard returned Janvier’s call from Sarajevo. Janvier ended his conversation and began speaking with Gobilliard.

The 7 p.m. request for Close Air Support was now an hour and a half old. Colonel Karremans in Srebrenica was calling General Nicolai in Sarajevo every fifteen minutes to see if it had finally been approved. Nicolai had no answer for him. De Jonge, whose idea it was to create the blocking position, could not believe how long it was taking.

At 8:45 p.m., Janvier was still on the phone. One of De Jonge’s aides announced that the Dutch were now firing directly at the Serbs. A few minutes later, a report arrived that the Dutch and the Muslims, fighting side by side, were engaged in a heavy firefight with the Serbs.

Kolsteren went to his office. Like his British, French and American counterparts, Kolsteren had a secure telephone line to the Ministry of Defense in his home country. In previous UN missions it had been clear that a military officer’s primary loyalty lay with his home country. But the mission in the former Yugoslavia had set new standards for intervention by individual countries in UN decision making.

Janvier’s request that Kolsteren call his government was an overt admission of what was well known in UN headquarters—the country with the most at stake on the ground in Bosnia had tacit control over UN decision making. During the May hostage crisis—when most of the hostages were French—it had been clear that the French government determined how the crisis would be handled.

Srebrenica was a Dutch dilemma. Carrying out Close Air Support might result in the Serbs killing thirty Dutch hostages. The flag-draped coffins would be returning to Holland, not UN headquarters in New York. In the end, Dutch politicians would suffer the consequences of the decision.

Kolsteren found Defense Minister Joris Voorhoeve in the basement bunker of the Dutch Defense Ministry at approximately 8:50 p.m. During every stage of the crisis all of the Dutch commanders—Karremans in Srebrenica, Brantz in Tuzla, Nicolai in Sarajevo and Kolsteren and De Jonge in Zagreb—had been conferring with their superiors in Holland on all major decisions.

The conversation was brief. Voorhoeve had known for days he might have to face this decision. After consulting with Dutch Prime Minister Wim Kok and Dutch Foreign Minister Hans Van Mierlo, Voorhoeve made one of the few courageous decisions surrounding the attack on Srebrenica. He decided that the lives of thirty Dutch peacekeepers were not worth more than the lives of 30,000 Muslims. The UN safe area and its people should be defended, Voorhoeve had concluded, no matter what the consequences were for the Dutch hostages. He told Kolsteren that the Dutch government had no objections to Close Air Support.

After the phone call ended, the mood in the Defense Ministry bunker was bleak. Dutch military officials expected the worst from the Serbs. Voorhoeve’s press aides sketched out the rough draft of a press release announcing the deaths of Dutch peacekeepers.

Over 450 Dutch lives hung in the balance. The Defense Minister appeared on the national news at 10 p.m. Over the last three days the Netherlands had become increasingly focused on Srebrenica.

Air strikes appear to be “inevitable,” a somber Voorhoeve warned. There is a “strong possibility” of Dutch casualties.

But in Zagreb, Janvier had not yet made up his mind. After speaking to Gobilliard in Sarajevo, the Force Commander continued to be on the phone. The unsigned forms waited on his desk.

At 9:05 p.m., Janvier spoke with Yasushi Akashi. He then spoke with Bosnian Serb general Zdravko Tolimir, the man who the day before denied to Nicolai that the Serbs were even attacking Srebrenica.

At 9:40 p.m., Janvier finally came back to the meeting. “We will be able to attack in half an hour,” he said. “The night option is OK if we have tanks or artillery attacking.”

Then one of Janvier’s aides entered the room and announced that fighting had stopped in Srebrenica. The Serbs had withdrawn from the hill overlooking the town. But the Serbs had issued an ultimatum of their own at 9 p.m. If the UN and all aid organizations surrendered all their weapons and equipment, they would be free to leave the enclave the next morning. All Muslims would be free to leave within forty-eight hours. But if the enclave did not surrender, the Serbs would resume their attack. Karremans himself, the aide said, had held a meeting with the Serb officer in command in the southern part of the enclave.

“If there is no move by the NGOs [aid groups] in the morning, the commanding officer said the Serbs will attack,” the aide warned. “The Dutch commanding officer does not consider it useful to have Close Air Support tonight. He wants it tomorrow morning.”

Karremans also wanted to know if he should abandon his remaining observation posts, which he felt should be “a command decision,” Janvier’s aide said, “not a tactical decision, because of the military and political impact.”

“No, I refuse to accept that,” Janvier said. “It’s a decision to be made on the ground.”

“It’s out of the question to leave the OPs at night anyway,” Janvier’s aide said.

As the discussion dragged on, a waiter in a red blazer began serving canapés and pouring red wine for each participant. The UN officers and officials had missed dinner and Janvier or one of his staff had ordered refreshments. As Srebrenica’s fate hung in the balance, Janvier’s Crisis Action Team sipped wine and nibbled on gourmet sandwiches.

Air operations chief Robert continued to lobby Janvier to approve Close Air Support. “The aircraft are already airborne over the Adriatic,” he said.

The planes were from the USS Theodore Roosevelt and were circling over the sea, awaiting orders. U.S. F-15s and other aircraft were equipped to carry out attacks at night. The flight to Srebrenica would take only twenty minutes.

“Can they keep them up all night?” Janvier asked.

“No. They wouldn’t have anything left for tomorrow,” he replied.

“If firing has stopped, it’s an indication that maybe the attack has stopped,” Janvier said. “Maybe Mladi has given an order.”

has given an order.”

“If the fighting has stopped it is not due to Mladi ’s order,” a frustrated De Jonge retorted. “It’s due to the fact that they can’t advance because of the Dutch blocking position.”

’s order,” a frustrated De Jonge retorted. “It’s due to the fact that they can’t advance because of the Dutch blocking position.”

Janvier had finally made his decision. “If someone asks why there was no CAS,” he said, “we say it was an infantry attack and CAS was too dangerous.” Janvier ignored the UN air operations chief’s and NATO liaison’s opinions that it was not dangerous.

De Jonge refused to give up. “The question is why is the BSA acting this way,” he said. “Is it to conquer Srebrenica? If so, the attack will continue.”

Robert warned that an air attack in the morning wouldn’t work. “There will be fog in Srebrenica tomorrow morning.”

Janvier ignored him. “I do not think Mladi wants to punish the enclave. He wants to punish Bosnia,” Janvier said, referring to the offensive to break the siege of Sarajevo and two others launched by the Muslim-led Bosnian Army that spring. “The Serbs are now involved in a process of negotiation, so it’s very strange they act this way.”